Abstract

Background

Bacterial meningitis (BM) is characterized by an intense host inflammatory reaction, which contributes to the development of brain damage and neuronal sequelae. Activation of the kynurenine (KYN) pathway (KP) has been reported in various neurological diseases as a consequence of inflammation. Previously, the KP was shown to be activated in animal models of BM, and the association of the SNP AADAT + 401C/T (kynurenine aminotransferase II - KAT II) with the host immune response to BM has been described. The aim of this study was to investigate the involvement of the KP during BM in humans by assessing the concentrations of KYN metabolites in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of BM patients and their relationship with the inflammatory response compared to aseptic meningitis (AM) and non-meningitis (NM) groups.

Methods

The concentrations of tryptophan (TRP), KYN, kynurenic acid (KYNA) and anthranilic acid (AA) were assessed by HPLC from CSF samples of patients hospitalized in the Giselda Trigueiro Hospital in Natal (Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil). The KYN/TRP ratio was used as an index of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity, and cytokines were measured using a multiplex cytokine assay. The KYNA level was also analyzed in relation to AADAT + 401C/T genotypes.

Results

In CSF from patients with BM, elevated levels of KYN, KYNA, AA, IDO activity and cytokines were observed. The cytokines INF-γ and IL-1Ra showed a positive correlation with IDO activity, and TNF-α and IL-10 were positively correlated with KYN and KYNA, respectively. Furthermore, the highest levels of KYNA were associated with the AADAT + 401 C/T variant allele.

Conclusion

This study suggests a downward modulatory effect of the KP on CSF inflammation during BM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the advances in antimicrobial and intensive care therapies against bacterial meningitis (BM), high mortality and morbidity rates have been observed [1]. Neurological sequelae, such as motor abnormalities, seizures, learning and memory impairment and mental retardation, are frequently reported after the disease. Cellular damage, mainly in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and inner ear are the histomorphological correlates of these neurofunctional deficits [2]-[4].

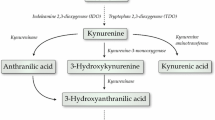

Bacterial invasion and proliferation within the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) induce an intense inflammatory response that leads to the activation of several metabolic pathways. One such pathway is the kynurenine (KYN) pathway (KP), which has been shown to be activated in experimental pneumococcal meningitis [5],[6]. The KP is the major route for tryptophan (TRP) oxidative degradation, and this pathway is involved in several diseases of the nervous system, including cancer, inflammatory disorders and neurodegenerative diseases [7]-[10]. The first step in the KP is the degradation of TRP catalyzed by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) to generate formylkynurenine, which is rapidly converted into KYN by the action of kynurenine formamidase. KYN can be partially metabolized to kynurenic acid (KYNA) and anthranilic acid (AA) by kynurenine aminotransferase and kynureninase, respectively, and in part converted to 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) by kynurenine 3-monooxygenase. Kynureninase also converts 3-HK to 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA), the substrate for 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid oxidase, which generates quinolinic acid (QUIN), the major substrate for NAD+ de novo synthesis [8],[9].

In the inflamed brain, TRP is metabolized through the KP to form neuroactive metabolites such as QUIN, an agonist of excitotoxic NMDA receptors, showing a cytotoxic effect, and KYNA, a neuroprotector antagonist of these NMDA receptors [10],[11]. Because the KP enzymes are differentially expressed in several cell types, quantitative differences in the production of neurotoxic and neuroprotective metabolites are observed [12]-[15], and an unbalance in the KP has been associated with several CNS diseases [7]-[10]. In an animal model of BM, the chemical inhibition of the KP led to decreased cellular NAD levels and increased apoptosis in the hippocampus [6]. This was associated with high activity of PARP-1, a DNA repair protein activated by DNA strand breaks caused by oxidative stress during BM. PARP-1 uses NAD+ as a cofactor, and its high activity induces energetic depletion, leading to the cell death and neuronal injury typical of BM [16]. Due to the involvement in NAD+ de novo synthesis and KYNA production, the KP is possibly a neuroprotective pathway in BM, despite its neurotoxic metabolites [6].

Important immunomodulatory properties, mainly related to the immunosuppressive effect of IDO, have also been attributed to this pathway [8],[9],[17]. A feedback mechanism in modulating the immune responses has been proposed because proinflammatory stimuli activate the KP and an anti-inflammatory effect mediated by KYNA has been observed [8],[18],[19]. IDO is preferentially induced by interferons, with IFN-γ being the main cytokine involved in its induction. A synergistic effect of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 in IDO induction was also described. However, there is evidence that IDO expression can also be induced by an IFN-γ-independent mechanism that involves NF-κB and stress-activated mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, such as p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). Conversely, an immune-suppressive effect of the KP has also been described. QUIN and 3-HAA induce the selective apoptosis of TH1 cells through the activation of the caspase pathway; B and NK cells are also susceptible to these compounds. In addition, the expression of IDO in dendritic cells induces the generation of regulatory T-cells. Thus, high levels of IDO will result in a decline of TH1 response, accompanied by an enhanced TH2 response. Moreover, KYNA shows an inhibitory effect on TNF-α at the transcriptional level and as a ligand of GPR35. This inhibition of TNF-α by KYNA may be an important factor in its neuroprotection [8],[9].

In a previous work, we identified the association of the SNP AADAT + 401C/T (kynurenine aminotransferase II -- KAT II) with the host immune response to BM, and our results suggested that this SNP may affect the host’s ability to recruit leukocytes to the infection site [20]. This evidence raises the hypothesis that the KP plays an important role in the pathogenesis of BM in humans. In the present work, we measured the concentrations of metabolites of the KP in CSF samples from patients with meningitis and analyzed their correlation with cytokines, inflammatory modulators previously reported to regulate the pathogenesis of BM. We also investigated the correlation of KAT II genotypes with KYNA levels and the disease.

Material and methods

Case selection and sample collection

This is a prospective study involving 28 patients with the clinical suspicion of meningitis who were admitted to the Giselda Trigueiro Hospital in Natal (Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil), a reference center for infectious diseases. Ethical approval for this study was given by Committees on Medical Ethics of the Giselda Trigueiro Hospital and by the National Committee in Ethics (CONEP) with number 0052.1.051.000-05. Informed consent was obtained from each patient participating in this study. For child patients, informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians.

Lumbar puncture (LP) was performed to obtain CSF for diagnostic purposes. Twenty-eight CSF samples were collected at the time of admission. Immediately after sampling, the CSF was kept at 4°C before centrifugation (400 × g, 5 minutes, 4°C). The supernatant were immediately frozen and stored at -80°C until assayed. The CSF samples were anonymized.

Thirteen patients were diagnosed with BM by the following criteria: (1) positive CSF bacterial culture, (2) detection of the pathogen in the CSF by gram staining plus clinical signs (acute onset, fever, meningeal irritation) and/or (3) positive blood culture or Gram stain in the presence of clinical signs of meningitis, (4) positive bacterial antigen detection in the CSF or blood using the latex agglutination test, with clinical signs of meningitis, and (5) clinical signs plus CSF parameters of increased protein content (>40 mg/dL), reduced glucose levels (<40 mg/dL) and the presence of CSF pleocytosis (≥500 cells/mm3), with predominantly polymorphonuclear granulocytes (PMN). Aseptic meningitis (AM) was diagnosed in seven patients by acute onset, fever, meningeal irritation signs, mild increase in protein content and normal glucose levels and the absence of the detection of bacterial pathogens. Because LP is a very invasive procedure, CSF samples were obtained only from patients undergoing procedures for the diagnosis of meningitis. Eight patients had a negative diagnosis for CNS infection and were included as non-meningitis controls (NM) (Table 1). Patients with confirmed acquired immunodeficiency syndrome were excluded from this study.

Analysis of kynurenine by HPLC

CSF was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to quantify the levels of TRP, KYN, KYNA and AA. Briefly, CSF samples were mixed 4:1 with 6% perchloric acid (PCA) to precipitate proteins. The acidified samples were centrifuged 10,000 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was filtered through 0.2-μm nylon membranes. An 80-μL aliquot of the filtrate was applied onto a C18 reverse-phase HPLC column (Supelcosil LC-18-DB, 15 cm × 4.6 mm, 3 μm; Supelco, Buchs, Switzerland) with a guard column (Supelguard LC-18-DB, 2 cm; Supelco, Buchs, Switzerland). TRP metabolites were eluted isocratically at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/minute with a mobile phase consisting of 100 mM zinc acetate and 3% acetonitrile (v/v), pH 6.2 [17],[18]. TRP and KYN were detected by UV absorption at 280 nm and 360 nm, respectively (L-4250 UV VIS Detector, Merck Hitachi). AA and KYNA were detected by fluorescence (F-1080 Fluorescence Detector, Merck Hitachi) at an excitation of 344 nm and emission of 400 nm. Chromatograms were generated and analyzed using D-7000 HPLC System Manager software.

Cytokine multiplex measurements

The concentration of six cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-1Ra) was assessed in CSF samples using the human cytokine Lincoplex Kit (HCYTO-60-K, Lincoplex®, Linco Research Inc., St Charles, MA, USA) with Luminex Technology (Bio-Plex 200 suspension array system, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were diluted to fit within the dynamic range of the assay. The cytokine concentrations were calculated by the Bio-Plex Manager software using a five-parametric logistic standard curve derived from the recombinant cytokine standards provided in the kit.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), with the Kruskal-Wallis test if needed (Prism 4.0, GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Multiple comparisons with Tukey’s test were performed if the distribution was normal. Differences between two groups were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test when the distribution was not normal and with Dunn’s post test when more than two groups were analyzed. The table and graph data are presented as the median ± interquartiles when not following a Gaussian distribution and the mean ± SEM when following a Gaussian distribution.

Results

Patients

Patients were divided into three groups, BM, AM and NM, according to the diagnostic criteria (Table 1). The CSF parameters found in the BM group were significantly different in comparison to those in the AM and NM groups. BM was diagnosed in 13 patients, and the causative pathogens were Streptococcus pneumoniae (n + 7), Neisseria meningitidis (n + 1) and Proteus mirabilis (n + 1); for 4 patients, the bacterial species could not be identified. Three patients died during hospitalization. Two belonged to the BM group and 1 to the AM group.

Concentration of tryptophan and KYN metabolites

Compared to the levels found in NM, a significant increase of KYN was observed in BM (P < 0.001) and AM (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). The KYNA levels in CSF were found to be significantly increased in BM compared to NM and AM (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively) (Figure 1). The CSF concentrations of AA showed significantly increased levels in BM versus NM (Figure 1).

Tryptophan (TRP), kynurenine (KYN), kynurenic acid (KYNA) and anthranilic acid (AA) concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from human patients. Each metabolite was analyzed independently between groups. Differences between groups were analyzed with multiple comparison using Dunn’s post test. P-value to one-way analysis with Kruskal-Wallis correction was lower than P < 0.05 to all metabolites, except TRP. Values are expressing as median ± interquartiles. ***P < 0.001 and *P < 0.05 compared to non-meningitis (NM); # P < 0.05 compared to aseptic meningitis (AM). Values that were below the detection limit were adjusted to the limit.

The ratio of KYN/TRP was calculated as an index of IDO activity in the CSF samples. The ratio between KYN and TRP determined in the CSF samples was significantly increased in BM compared to NM (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). AM showed no significant difference with regard to the KYN/TRP ratio compared to NM. KYN concentrations of NM patients that were below of the detection limit (10 nM) were adjusted to this value.

Kynurenine to tryptophan (KYN/TRP) ratio indicates indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity. Increased enzymatic activity was found for IDO in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples. Values are expressing as median ± interquartiles. Data showed P < 0.01 to one-way analysis with Kruskal-Wallis correction. Differences between two groups were analyzed with Dunn’s post test. Values that were below the detection limit were adjusted to the limit.

Concentrations of cytokines

The concentrations of the six cytokines, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-1Ra, were significantly upregulated in CSF during BM when compared to the NM control group (Figure 3). Despite the AM group show an increase in some cytokines, for example, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10 and IL-1Ra, significant differences compared to the NM group were not observed.

Comparison of the cytokines levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) during meningitis. Values are expressing as median ± interquartiles. Data showed P < 0.01 to one-way analysis with Kruskal-Wallis correction. Differences between two groups were analyzed with Dunn’s post test. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 compared to non-meningitis (NM). # P < 0.05 compared to aseptic meningitis (AM).

Furthermore, a positive correlation between the concentrations of IFN-γ and IL-1Ra with IDO activity was found in the BM patients, as well as between TNF-α versus KYN and KYNA versus IL-10 (Table 2).

Correlation of genotype and KYNA levels

In a previous work, we obtained the genotype of these patients in relation to SNP AADAT + 401C/T (KAT II) and observed a high frequency of the T allele and TT genotype in BM patients [20]. As the number of patients in our study was small for polymorphism association, we first analyzed all the patients in the study only according to genotype. In this first analysis, the patients carrying the T variant allele showed an increased KYNA concentration (Figure 4A). Thereafter, the largest group of individuals, in this case the heterozygotes (CT), was divided into two groups considering their disease, as shown in Figure 4B. The obtained data showed the contribution of acute BM combined with the variant allele in the increase of KYNA levels. Individuals with acute BM were also analyzed according to genotype, and the highest KYNA levels were observed to be associated with the TT genotype, however no significant difference was observed (Figure 4C).

Influence of the individual genotype on the levels of kynurenic acid (KYNA). Patients showing polymorphisms in the KAT II gene demonstrated increase in the KYNA concentration. All patients in the study were split according genotype. (A) Patients homozygous for variant allele (TT) showed higher KYNA concentration than heterozygous (CT) and homozygous for wild type allele (CC). (B) Patients with genotype CT were divided in two groups according to disease showing the contribution of bacterial meningitis (BM) combined with the variant allele in the elevated concentration of KYNA. (C) Patients with BM were split according to their genotype and KYNA levels were compared but no significant difference was found. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM in graph (A) and median ± interquartiles in (B) and (C). Data in graph (A) showed Gaussian distribution and were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post test Tukey’s test to compare all genotypes, while in graphs (B) and (C), differences between groups were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test and Dunn’s post test, respectively.

Discussion

CSF concentrations of KP metabolites have been demonstrated in a variety of neurological diseases [7]-[10]. In the present study, the concentration of TRP and three KYN metabolites, IDO activity and cytokines were assessed in the CSF of patients with meningitis. The obtained data demonstrated an increase in KYN metabolites in CSF and suggested a role of IDO, kynureninase and anthranilate 3-hydroxylase in accelerating the synthesis of KYN, KYNA and AA in human BM patients, corroborating the findings from animal models [5],[6].

Inflammation in the CNS results in the recruitment of activated T-cells and macrophages from the periphery into the neural parenchyma [21]. Activated T-cells produce cytokine mediators of the inflammatory response, including the macrophage-activating cytokine IFN-γ, which induces IDO activity [22],[23]. In our work, TRP levels are not altered in the CSF of patients with BM or AM compared to NM. However, efficient conversion of TRP to KYN could be documented. IDO activity in the CSF was significantly higher only in the BM group, in agreement with the low IFN-γ level observed in the AM group. Conversely, a strong immune response during BM has been positively correlated with IDO activity. In some non-inflammatory and inflammatory diseases including BM, the CSF QUIN, KYN and KYNA levels were also correlated with immune markers, such as neopterin, white blood cell counts and lgG levels, indicating a close relationship between the KP and the brain’s inflammatory response [24].

Reports linking increased KYN metabolism with neuronal injury, particularly during neuroinflammatory disease, have emerged. This neuronal injury would be mainly attributed to the production of neurotoxic metabolites and oxidative molecules, such as superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide, during the metabolism of KYN [7]-[10],[25],[26]. In contrast, in vitro studies have attributed antioxidant activity to certain KP metabolites [27]-[29].

Due to these roles, the KP has been investigated as a target for therapeutic intervention. The pharmacological modulation of KYN metabolism can affect de novo NAD synthesis [6],[30]. NAD is involved in many metabolic processes, being an essential co-factor for several enzymes, including PARP-1, which plays a crucial role in the development of meningitis-associated central nervous system complications [16]. In this sense, the KP intervention can affect NAD production and consequently PARP-1 activity, as the inhibition of the KP induced an increase in apoptosis in a BM animal model [6].

During the course of bacterial meningitis, anti-inflammatory cytokines are produced to mitigate the induced inflammation [4],[31]. Some studies have proposed that cells of the immune system use a bidirectional communication in which TRP catabolism through IDO activity drives the generation of IL-10-producing regulatory T-cells [8],[9],[18],[19]. In BM patients, we observed a positive correlation between IDO activity and the inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and IL-1Ra (Table 2). Although each cytokine displays different roles in the inflammation during BM, IFN-γ seems to have a crucial role, mainly during pneumococcal meningitis [32]-[35], showing to be involved in deleterious proinflammatory effects [34],[35]. Concomitantly, KYN metabolites showed a positive correlation with TNF-α and KYNA metabolites with IL-10. In contrast, AM did not show a strong immune response or a high level of IL-10, despite a significant amount of KYN in the comparison with the NM group. Therefore, we propose that KYN metabolites alone are not able to trigger the cascade of inflammatory mediator production. In animal models, long-term diurnal hypoactivity and nocturnal hyperactivity have been reported in wild-type mice, while these changes were not observed in IDO1(-/-) mice. However, no protection against developing long-term cognitive deficits was observed in IDO deficient mice. These data suggest that KP may be involved in some behavioural sequelae of pneumococcal meningitis and may acts synergistically, or independently of, other metabolic pathways to cause different types of neurological sequelae [36].

Recently, our group demonstrated that a polymorphism in the kynurenine aminotransferase II gene (AADAT + 401C/T) was associated with reduced levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MIP-1 /CCL3 and MIP-1/CCL4 in BM patients; a reduction in cell count with a high correlation with cytokine and chemokine levels was also observed, suggesting a reduced leukocyte recruitment ability in these patients [20]. This SNP is located in a putative exonic splicing silencer (ESS), which may result in a quantitative increase in the production of mRNAs and protein [37]. In agreement with this proposition, analyzing the data from KYNA measurements in the patients homozygous for the TT genotype and comparing with the CC homozygous, we observed an increase in KYNA levels (Figure 4). Interestingly, our results demonstrated a positive correlation between KYNA and IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine that was previously reported to down-regulate the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. Similar data were obtained in a study carried out by Hsieh et al., showing that KYNA improves the outcomes of heatstroke in rats. In this model, KYNA inhibited the expression of inflammatory molecules such as TNF-α and ICAM-1 and enhanced IL-10 levels [19]. Corroborating the findings regarding neuroprotection, the reduced production of KYNA in astrocytes has been proposed to increase neurological symptoms of cerebral malaria [38]. KYNA was identified as a ligand for the receptor for GPR35, as it was able to attenuate LPS-induced TNF-α secretion in a dose-dependent manner. Because the TRP metabolic pathway is activated by proinflammatory stimuli, the anti-inflammatory effect of KYNA suggests an interesting feedback mechanism in modulating immune responses [18].

In addition to cytokines, other molecules can regulate the KP. There are known interactions between TRP depletion and nitric oxide (NO) production. Several findings have demonstrated that NO is able to inhibit the IDO enzyme by direct interaction or accelerating proteasomal degradation [39],[40]. Furthermore, as shown in the report from Samelson-Jones and Yeh, several cellular factors, including pH, redox environment, NO, and L-Trp abundance can be considered as additional aspects in the regulation of IDO activity [41].

Altogether, these findings suggest that IDO has prominent importance during bacterial meningitis due to the following: its capacity to maintain PARP-1 activity through NAD synthesis, protecting against cell death [6],[16]; the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), helping the defense mechanisms in addition to maintaining IDO activity [8]-[10],[26]; its capacity to produce some antioxidant metabolites [27]; and regulating the immune response via the known vessel-relaxing ability which KYN possess during inflammation and other immunosuppressive mechanisms [18],[19],[42]. We also suggest that AADAT + 401C/T patients can present a better outcome during BM disease via a reduced inflammatory response and increased capacity of the neuroprotective role of KYNA, which requires further investigation. Conversely, this reduced response to a pathogen at the beginning of infection may favor invasion of the microorganism, increasing the susceptibility to BM. However, the small number of patients analyzed and the heterogeneity between the groups are limitations of our work, making necessary further studies with a larger cohort for a better understanding of the role of KYNA in the outcome of bacterial meningitis.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate a specific upregulation of the KP in BM patients and suggest that KYN metabolites contribute directly to the disease. Despite the neurotoxic properties reported in the literature to date, we propose a positive and essential role of this metabolic pathway in BM.

Authors’ contributions

LGC, SLL and LFAL proposed the study design. LGC, SC, CLB, FRSS, FLF and DG performed the assays and data analysis. LGC, SC, SLL and LFAG wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

Auburtin M, Wolff M, Charpentier J, Varon E, Le Tulzo Y, Girault C, Mohammedi I, Renard B, Mourvillier B, Bruneel F, Ricard JD, Timsit JF: Detrimental role of delayed antibiotic administration and penicillin-nonsusceptible strains in adult intensive care unit patients with pneumococcal meningitis: the PNEUMOREA prospective multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2006, 34: 2758-2765. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239434.26669.65.

Bedford H: Prevention, treatment and outcomes of bacterial meningitis in childhood. Prof Nurse. 2001, 17: 100-102.

Lepage P, Dan B: Infantile and childhood bacterial meningitis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013, 112: 1115-1125. 10.1016/B978-0-444-52910-7.00031-3.

Neal JW, Gasque P: How does the brain limit the severity of inflammation and tissue injury during bacterial meningitis?. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013, 72: 370-385. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182909f2f.

Bellac CL, Coimbra RS, Christen S, Leib SL: Pneumococcal meningitis causes accumulation of neurotoxic kynurenine metabolites in brain regions prone to injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2006, 24: 395-402. 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.014.

Bellac CL, Coimbra RS, Christen S, Leib SL: Inhibition of the kynurenine-NAD + pathway leads to energy failure and exacerbates apoptosis in pneumococcal meningitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010, 69: 1096-1104. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181f7e7e9.

Fatokun AA, Hunt NH, Ball HJ: Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2 (IDO2) and the kynurenine pathway: characteristics and potential roles in health and disease. Amino Acids. 2013, 45: 1319-1329. 10.1007/s00726-013-1602-1.

Mándi Y, Vécsei L: The kynurenine system and immunoregulation. J Neural Transm. 2012, 119: 197-209. 10.1007/s00702-011-0681-y.

Campbell BM, Charych E, Lee AW, Möller T: Kynurenines in CNS disease: regulation by inflammatory cytokines. Front Neurosci. 2014, 8: 12-10.3389/fnins.2014.00012.

Reyes Ocampo J, Lugo Huitrón R, González-Esquivel D, Ugalde-Muñiz P, Jiménez-Anguiano A, Pineda B, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Ríos C, Pérez de la Cruz V: Kynurenines with neuroactive and redox properties: relevance to aging and brain diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014, 2014: 646909-10.1155/2014/646909.

Leib SL, Kim YS, Ferriero DM, Tauber MG: Neuroprotective effect of excitatory amino acid antagonist kynurenic acid in experimental bacterial meningitis. J Infect Dis. 1996, 173: 166-171. 10.1093/infdis/173.1.166.

Guillemin GJ, Smith DG, Smythe GA, Armati PJ, Brew BJ: Expression of the kynurenine pathway enzymes in human microglia and macrophages. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003, 527: 105-512. 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_12.

Guillemin GJ, Smythe G, Takikawa O, Brew BJ: Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and production of quinolinic acid by human microglia, astrocytes, and neurons. Glia. 2005, 49: 15-23. 10.1002/glia.20090.

Braidy N, Grant R, Adams S, Brew BJ, Guillemin GJ: Mechanism for quinolinic acid cytotoxicity in human astrocytes and neurons. Neurotox Res. 2009, 16: 77-86. 10.1007/s12640-009-9051-z.

Manéglier B, Malleret B, Guillemin GJ, Spreux-Varoquaux O, Devillier P, Rogez-Kreuz C, Porcheray F, Thérond P, Dormont D, Clayette P: Modulation of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase expression and activity by HIV-1 in human macrophages. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2009, 23: 573-581. 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00703.x.

Koedel U, Winkler F, Angele B, Fontana A, Pfister HW: Meningitis-associated central nervous system complications are mediated by the activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002, 22: 39-49. 10.1097/00004647-200201000-00005.

Puccetti P, Grohmann U: IDO and regulatory T cells: a role for reverse signalling and non-canonical NF-kappaB activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007, 7: 817-823. 10.1038/nri2163.

Wang J, Simonavicius N, Wu X, Swaminath G, Reagan J, Tian H, Ling L: Kynurenic acid as a ligand for orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR35. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281: 22021-22028. 10.1074/jbc.M603503200.

Hsieh YC, Chen RF, Yeh YS, Lin MT, Hsieh JH, Chen SH: Kynurenic acid attenuates multiorgan dysfunction in rats after heatstroke. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011, 32: 167-174. 10.1038/aps.2010.191.

de Souza FR, Fontes FL, da Silva TA, Coutinho LG, Leib SL, Agnez-Lima LF: Association of kynurenine aminotransferase II gene C401T polymorphism with immune response in patients with meningitis. BMC Med Genet. 2011, 12: 51-10.1186/1471-2350-12-51.

Mucke L, Eddleston M: Astrocytes in infectious and immune-mediated diseases of the central nervous system. Faseb J. 1993, 7: 1226-1232.

Schroten H, Spors B, Hucke C, Stins M, Kim KS, Adam R, Däubener W: Potential role of human brain microvascular endothelial cells in the pathogenesis of brain abscess: inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus by activation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Neuropediatrics. 2001, 32: 206-210. 10.1055/s-2001-17375.

Adam R, Rüssing D, Adams O, Ailyati A, Sik Kim K, Schroten H, Däubener W: Role of human brain microvascular endothelial cells during central nervous system infection. Significance of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in antimicrobial defence and immunoregulation. Thromb Haemost. 2005, 94: 341-346.

Heyes MP, Saito K, Crowley JS, Davis LE, Demitrack MA, Der M, Dilling LA, Elia J, Kruesi MJ, Lackner A, Larsen SA, Lee K, Leonard HL, Markey SP, Martin A, Milstein S, Mouradian MM, Pranzatelli MR, Quearry BJ, Salazar A, Smith M, Strauss SE, Sunderland T, Swedo SW, Tourtellotte WW: Quinolinic acid and kynurenine pathway metabolism in inflammatory and non-inflammatory neurological disease. Brain. 1992, 115: 1249-1273. 10.1093/brain/115.5.1249.

Hiraku Y, Inoue S, Oikawa S, Yamamoto K, Tada S, Nishino K, Kawanishi S: Metal-mediated oxidative damage to cellular and isolated DNA by certain tryptophan metabolites. Carcinogenesis. 1995, 16: 349-356. 10.1093/carcin/16.2.349.

Goldstein LE, Leopold MC, Huang X, Atwood CS, Saunders AJ, Hartshorn M, Lim JT, Faget KY, Muffat JA, Scarpa RC, Chylack LT, Bowden EF, Tanzi RE, Bush AI: 3-hydroxykynurenine and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid generate hydrogen peroxide and promote alpha-crystallin cross-linking by metal ion reduction. Biochemistry. 2000, 39: 7266-7275. 10.1021/bi992997s.

Christen S, Peterhans E, Stocker R: Antioxidant activities of some tryptophan metabolites: possible implication for inflammatory diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990, 87: 2506-2510. 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2506.

Leipnitz G, Schumacher C, Dalcin KB, Scussiato K, Solano A, Funchal C, Dutra-Filho CS, Wyse AT, Wannmacher CM, Latini A, Wajner M: In vitro evidence for an antioxidant role of 3-hydroxykynurenine and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid in the brain. Neurochem Int. 2007, 50: 83-94. 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.04.017.

Thomas SR, Stocker R: Antioxidant activities and redox regulation of interferon-gamma-induced tryptophan metabolism in human monocytes and macrophages. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999, 467: 541-552. 10.1007/978-1-4615-4709-9_67.

Grant R, Kapoor V: Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity in IFN-gamma stimulated astroglioma cells decreases intracellular NAD levels. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003, 66: 1033-1036. 10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00464-7.

Wennekamp J, Henneke P: Induction and termination of inflammatory signaling in group B streptococcal sepsis. Immunol Rev. 2008, 225: 114-127. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00673.x.

Kornelisse RF, Hack CE, Savelkoul HF, van der Pouw Kraan TC, Hop WC, van Mierlo G, Suur MH, Neijens HJ, de Groot R: Intrathecal production of interleukin-12 and gamma interferon in patients with bacterial meningitis. Infect Immun. 1997, 65: 877-881.

Glimaker M, Olcén P, Andersson B: Interferon-gamma in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with viral and bacterial meningitis. Scand J Infec Dis. 1994, 26: 141-147. 10.3109/00365549409011777.

Mitchell AJ, Yau B, McQuillan JA, Ball HJ, Too LK, Abtin A, Hertzog P, Leib SL, Jones CA, Gerega SK, Weninger W, Hunt NH: Inflammasome-dependent IFN-γ drives pathogenesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis. J Immunol. 2012, 189: 4970-4980. 10.4049/jimmunol.1201687.

Too LK, Ball HJ, McGregor IS, Hunt NH: The pro-inflammatory cytokine interferon-gamma is an important driver of neuropathology and behavioural sequelae in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Brain Behav Immun. 2014, 40: 252-268. 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.02.020.

Too LK, McQuillan JA, Ball HJ, Kanai M, Nakamura T, Funakoshi H, McGregor IS, Hunt NH: The kynurenine pathway contributes to long-term neuropsychological changes in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Behav Brain Res. 2014, 270: 179-195. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.05.018.

Kralovicova J, Vorechovsky I: Global control of aberrant splice-site activation by auxiliary splicing sequences: evidence for a gradient in exon and intron definition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35: 6399-6413. 10.1093/nar/gkm680.

Hunt NH, Golenser J, Chan-Ling T, Parekh S, Rae C, Potter S, Medana IM, Miu J, Ball HJ: Immunopathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Int J Parasitol. 2006, 36: 569-582. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.02.016.

Hucke C, MacKenzie CR, Adjogble KD, Takikawa O, Daubener W: Nitric oxide-mediated regulation of gamma interferon-induced bacteriostasis: inhibition and degradation of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Infect Immun. 2004, 72: 2723-2730. 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2723-2730.2004.

Entrena A, Camacho ME, Carrión MD, López-Cara LC, Velasco G, León J, Escames G, Acuña-Castroviejo D, Tapias V, Gallo MA, Vivó A, Espinosa A: Kynurenamines as neural nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2005, 48: 8174-8181. 10.1021/jm050740o.

Samelson-Jones BJ, Yeh SR: Interactions between nitric oxide and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Biochemistry. 2006, 45: 8527-8538. 10.1021/bi060143j.

Wang Y, Liu H, McKenzie G, Witting PK, Stasch JP, Hahn M, Changsirivathanathamrong D, Wu BJ, Ball HJ, Thomas SR, Kapoor V, Celermajer DS, Mellor AL, Keaney JF, Hunt NH, Stocker R: Kynurenine is an endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced during inflammation. Nat Med. 2010, 16: 279-285. 10.1038/nm.2092.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by UBS Optimus Foundation and CNPq-Brazil. We thank to Dr. Roney S Coimbra for participation in the initiation of the project. We also thank the team of Hospital Giselda Trigueiro for their help with sample collection. The authors LGC and LFAL are grateful to CNPq-Brazil for the fellowships.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Coutinho, L.G., Christen, S., Bellac, C.L. et al. The kynurenine pathway is involved in bacterial meningitis. J Neuroinflammation 11, 169 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-014-0169-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-014-0169-4