Abstract

Background

Studies on prevalence rates of mental comorbidities in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) have reported varying results and provided limited information on related drugs. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of selected mental health diagnoses and the range of associated drug prescriptions among adolescents and young adults (AYA) with JIA compared with general population controls.

Findings

Nationwide statutory health insurance data of the years 2020 and 2021 were used. Individuals aged 12 to 20 years with an ICD-10-GM diagnosis of JIA in ≥ 2quarters, treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and/or glucocorticoids were included. The frequency of selected mental health diagnoses (depression, anxiety, emotional and adjustment disorders) was determined and compared with age- and sex-matched controls. Antirheumatic, psychopharmacologic, psychiatric, and psychotherapeutic therapies were identified by Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes and specialty numbers. Based on data from 628 AYA with JIA and 6270 controls, 15.3% vs. 8.2% had a diagnosed mental health condition, with 68% vs. 65% receiving related drugs and/or psychotherapy. In both groups, depression diagnosis became more common in older teenagers, whereas emotional disorders declined. Females with and without JIA were more likely to have a mental health diagnosis than males. Among AYA with any psychiatric diagnosis, 5.2% (JIA) vs. 7.0% (controls) received psycholeptics, and 25% vs. 27.3% psychoanaleptics.

Conclusions

Selected mental health conditions among 12-20-year-old JIA patients are diagnosed more frequently compared to general population. They tend to occur more frequently among females and later in childhood. They are treated similarly among AYA regardless of the presence of JIA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common chronic rheumatic disease in pediatrics describing a heterogeneous group of inflammatory rheumatic diseases of unknown origin [1]. Affected individuals typically suffer from acute pain and swelling, but also from joint damage and comorbid conditions that might develop during the course of their disease [2]. Resulting limitations in daily life, time-consuming physical therapies, and medication side effects can fuel dissatisfaction and psychological distress, which in turn detoriates disease self-management and treatment adherence [3,4,5]. Typical issues faced by adolescents are therefore compounded by the challenge of managing their chronic disease [6].

Previous studies among adolescents with JIA have found an increased risk for mental health impairments; however, rates of symptoms and diagnoses have varied widely [3, 7,8,9,10]. Most of the existing studies focused on mental health issues using self-report questionnaires and from a quality of life perspective. Their statements were partly limited by small sample sizes, lack of controls or missing information on related drug prescriptions [3].

In this study, we aimed to use health insurance data to determine the prevalence of diagnosed selected mental health conditions and their medication and psychotherapeutic treatment in AYA with JIA compared to a control group from the general population.

Findings

Methods

Cross-sectional BARMER claims data collected in the years 2020 and 2021 were used. The BARMER statutory health insurance fund is one of the largest health insurance companies in Germany and covers around 660,000 adolescents aged 12-20 years, corresponding to around 11% of all juvenile inhabitants of this age group with a statutory health insurance [11]. Germany has health care coverage for all permanent residents, allowing them to have access to the statutory health insurance system. There is no co-payment for treatment for people under 18 years of age and low co-payment rate for adults (e.g. up to 10 euros for a prescription for medication).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age between 12 to 20 years, 2) continuous insurance in 2020 and 2021, 3) at least one International Statistical Classification of Diseases German Modification (ICD-10-GM) code for JIA in at least two quarters of 2020 or 2021, 4) at least one of the following ICD-10-GM codes present before the age of 16 years: Juvenile arthritis (M08.X, M09.0 and L40.5†) and/or M45.0, M46.0, M46.8, M46.9, M07.0-3/L40.5, M05.X, M06.0, M06.1), and 5) at least one prescription for a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) or systemic glucocorticoid therapy in order to increase the reliability of diagnosis.

JIA was categorized into the following categories: polyarthritis, adult type (M08.0), enthesitis-related arthritis/juvenile spondyloarthritis (M08.1), systemic JIA (M08.2), RF- polyarthritis (M08.3), oligoarthritis (M08.4), psoriatic arthritis (M09.0) and undifferentiated JIA (M08.8, M08.9). When conflicting diagnoses were recorded in the same individual, only one diagnosis was assigned using the following hierarchy: M08.0, M08.1, M08.2, M08.3, M09.0, M08.4, M08.8/M08.9. If e.g. someone had an ICD-10-GM diagnosis of both M08.1 and M08.8 in their data, they were assigned to the enthesitis-related arthritis/juvenile spondyloarthritis (M08.1) group.

For each AYA with JIA we matched 10 controls with the same sex and age. Controls were randomly selected in the population without any condition of JIA in the complete years 2020 or 2021 as defined in the inclusion criteria. Controls were eligible independent of how often they visited a doctor’s office in 2020 or 2021 (it was possible that controls had no visits).

(Anti)rheumatic therapies and care

Antirheumatic therapies were identified using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes and included conventional synthetic (cs)DMARDs (azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, mycophenolate, sulfasalazine), biologic (b)DMARDs (abatacept, adalimumab, anakinra, canakinumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, sarilumab, secukinumab, tocilizumab), targeted synthetic (ts)DMARDs (baricitinib, tofacitinib), nonsteroidal antirheumatic drugs (NSAIDs) and systemic glucocorticoids (GCs). Rheumatology care was identified by specific billing codes for juvenile and adult rheumatology and by a specialist physician number for adult internal rheumatology.

Diagnoses and therapy of psychological morbidities

The following diagnoses were identified by ICD-10-GM codes: depression (F32, F33, F34, F38), anxiety disorders (F40,41), emotional disorders (F92, F93) and adjustment disorders (F43). Prescribed drugs related to psychological disorders include psycholeptics (N05), such as antipsychotics (N05A), anxiolytics (N05B), sedatives (N05C) as well as homeopathic psycholeptics (N05H), and psychoanaleptics (N06), such as antidepressants (N06A), non-selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors (N06AA) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (N06AB). All drugs prescribed at least once in 2020 or 2021 are reported. Psychological/psychiatric therapy was identified by physician specialist numbers. The Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) dispensed are reported, providing information on the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication [12]. All ICD-10-GM, ATC-codes, physician specialist numbers and billing codes are reported in Suppl. Table S1.

Statistical analysis

Results are provided for AYA with JIA and controls, stratified by sex and age groups: 12-14, 15-17, and 18-20 years. In order to exclude accidental identifiability or inferences to individuals, no data is presented in groups with a case number <30. The frequencies among groups were compared using a Chi-square-Test as appropriate. As part of a sensitivity analysis, we also determined the frequency of psychological disorders based on data from 2019. The short report was written in accordance with the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement [13].

Results

In total, 628 AYA with JIA and 6,270 age- and sex-matched controls were included in the study. One of the AYA with JIA is of “diverse” gender, for this person we did not find matched controls. A flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

Of the 88% of AYA with JIA receiving DMARD therapy, about 48% received a TNF-inhibitor and 50% methotrexate. Female adolescents more often had csDMARDs (f 54% vs. m 45%) and NSAIDs (49% vs. 41%), while males were more frequently prescribed bDMARDs (f 54% vs. m 63%). Systemic glucocorticoids and bDMARDs were increasingly used with higher ages, while methotrexate was more often used in younger adolescents. bDMARD therapy was most frequent in systemic JIA and polyarthritis. More information on the characteristics and antirheumatic therapy is presented in Table 1.

Psychological disorders and related drug prescription

Among 628 AYA with JIA, 15.3% (n=96) had any of the selected psychological diagnoses. In comparison, 8.2% (n=513) of controls were found to have a psychological diagnosis. In 2019, 16.0% of 506 patients and 7.3% of 5050 controls had one of these diagnoses. As shown in Fig. 2 adjustment disorders were diagnosed most frequently (JIA vs. controls: 8.0% vs. 2.8%, p(Chi-square) <0.001) followed by depression (5.1% vs. 3.5%, p(Chi-square) =0.04), emotional disorders (3.5% vs. 1.7%, p(Chi-square) =0.02), and anxiety disorders (3.2% vs. 2.5%, p(Chi-square) =0.29).

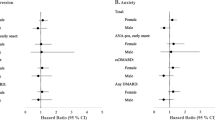

Depression and anxiety were most common among individuals aged 18 to 20 year old among both JIA and control groups, whereas emotional disorders were diagnosed primarily among 12- to 14-year-olds (Fig. 3). Female patients were more likely to have depression than males. A psychiatric diagnosis was found more frequently in patients with oligoarthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis, or psoriatic arthritis than in patients with systemic JIA or polyarthritis (Fig. 4). More details on characteristics of AYA with and without a psychological diagnosis are shown in Table 2.

Taking into account all persons who either had a diagnosed mental disorder or were being treated with related drugs or psychotherapy, 16.7% of AYA with JIA and 8.8% of controls were affected. About 7% of AYA with JIA had been diagnosed with depression or were taking an antidepressant.Among AYA with JIA diagnosed with any psychological disorder (n=96), 68% received related drugs and/or psychotherapy. This was also the case for a comparable proportion of controls diagnosed with any psychological disorder (65%). Psychotherapy, psychoanaleptics, and psycholeptics were documented with comparable frequency in the JIA and control group, whereas controls were more likely to have a prescription for psychiatric therapy (Table 2). Psychoanaleptics, especially antidepressants, and psycholeptics were only prescribed from the age of 15 and most frequently used in those aged 18 to 20 years. While mean DDDs for NSAIDs were similar in AYA with (101) and without (101) any psychological disorder, mean DDDs for GCs were lower (80) in AYA with than in AYA without any psychological disorder (106).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study on mental comorbidities in pediatric JIA patients and controls is based on one of the largest samples analyzing a wide range of prescribed medications related to mental health problems using health insurance data. We found that AYA with JIA had a higher risk of a mental health diagnosis than the control population.

A few previous studies on psychiatric morbidity in JIA have also highlighted an increased risk in specific outcomes compared with controls [7, 14,15,16,17]. Although our findings are in line with these results, comparability is mostly limited due to methodological discrepancy. Small heterogeneous samples as well as differences in case assessment (symptoms vs. diagnoses) and/or disease durations/activities may explain why few previous studies have stated no increased risk of mental health issues in JIA patients compared to general population controls [18,19,20]. In our study, the prevalence rate of psychological diagnoses seemed to be higher among females than among males, both in AYA with and without JIA. These results are consistent with trends in the general population [21] and those previously reported in JIA [14, 17, 20, 22]. We have shown that prevalence rates of selected mental disorders vary with age, with depression and anxiety diagnoses becoming increasingly common. Thus, our findings confirm previous studies on the relationship between age and mental health in JIA [19, 22, 23]. In our study, individuals with oligoarthritis more frequently had mental health diagnoses than individuals with polyarthritis. Conversely to our findings, previous studies showing that patients with a polyarticular course are at higher risk for mental health impairments than patients from other categories [3, 22]. However, since factors such as JIA onset, disease duration, sex, and age can influence the frequency and type of mental disorders [14], comparability with previous studies is limited. We found that about two thirds of individuals with JIA and diagnosed mental disorder were undergoing psychotherapeutic or psychopharmacological treatment. The similar proportion of controls with psychological disorders receiving treatment shows that JIA patients seem to have the same chance to receive treatment for diagnosed mental health issues than controls.

Limitations and strengths

Our study had several limitations, including not clinically validated diagnoses of JIA and mental disorders. Therefore, prescriptions of DMARDS and/or GC were included to increase diagnostic reliability of JIA. Specialist contact may be underestimated as specialists working in general practitioners’ offices or in outpatient settings within university hospitals are not identifiable as rheumatologists in the data. The higher prevalence of mental disorders in patients compared to controls could also be due to the fact that patients have regular medical encounters, can express mental problems and have easier access to psychological/psychiatric care. This may also have been the case during the corona pandemic (when patients still had regular medical encounters). In addition, the pandemic itself as remarkable stressor may also have played a role. In order to rule out the latter, a sensitivity analysis was carried out, which, however, came to comparable results based on data from the pre-corona period. The study was not designed to address drug-related associations with depression or other mental disorders.

Despite these limitations, our data cover a broad nationwide DMARD/glucocorticoid-treated JIA cohort, representing about 4.5% of the estimated JIA population in Germany [24]. Strengths of claims data include the possibility to identify sex- and age matched controls without arthritis diagnoses. A main advantage of the data source is the complete coverage of all prescribed drugs.

Conclusion

Selected psychological disorders among 12- to 20-year-olds with JIA are diagnosed more frequently than in controls without JIA. They are diagnosed with varying frequency across the age range and JIA categories, and are more common in females than males. Mental health issues are treated proportionally equally in adolescents with JIA compared to controls.

Availability of data and materials

No additional data are available.

Abbreviations

- AYA:

-

Adolescents and young adults

- JIA:

-

Juvenile idiopathic Arthritis

- DMARDs:

-

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

- ICD-10:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases

- ICD-10-GM:

-

German modification of the ICD-10

- ATC:

-

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- GCs:

-

Glucocorticoids

- DDDs:

-

Defined Daily Doses

References

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:390–2.

Petty RE, Laxer RM, Wedderburn LR. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. In: Petty RE, Laxer RM, Lindsley CB, Wedderburn LR, editors. Textbook of pediatric rheumatology. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. p. 188–204.

Fair DC, Rodriguez M, Knight AM, Rubenstein TB. Depression and anxiety in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: current insights and impact on quality of life, a systematic review. Open Access Rheumatol Res Rev. 2019;11:237–52.

Szulczewski L, Mullins LL, Bidwell SL, Eddington AR, Pai ALH. Meta-analysis: care giver and youth uncertainty in pediatric chronic illness. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;42:395–421.

Davis AM, Graham TB, Zhu Y, McPheeters ML. Depression and medication nonadherence in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2018;27:1532–41.

Christie D, Viner R. Adolescent development. BMJ. 2005;330:301–4.

Pedersen MJ, Høst C, Hansen SN, Deleuran BW, Bech BH. Psychiatric Morbidity Is Common Among Children With Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A National Matched Cohort Study. J Rheumatol. 2023. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37321635.

Delcoigne B, Horne A, Reutfors J, Askling J. Risk of psychiatric disorders in Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: population- and sibling-controlled cohort and cross-sectional analyses. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2023;5:277–84.

Roemer J, Klein A, Horneff G. Prevalence and risk factors of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2023;43:1497–505.

Li L, Merchant M, Gordon S, Lang B, Ramsey S, Huber AM, Gillespie J, Lovas D, Stringer E. High Rates of symptoms of major depressive disorder and panic disorder in a Canadian sample of adolescents with Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2023;50:804–8.

Statista. Bevölkerung - Zahl der Einwohner in Deutschland nach relevanten Altersgruppen am 31. Dezember 2022. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1365/umfrage/bevoelkerung-deutschlands-nach-altersgruppen. Accessed 18 Aug 2023.

World Health Organization. ATC/DDD Toolkit. https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/about. Accessed 13 Aug 2023.

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001885.

Kyllönen MS, Ebeling H, Kautiainen H, Puolakka K, Vähäsalo P. Psychiatric disorders in incident patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis - a case-control cohort study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021;19:105.

Bomba M, Meini A, Molinaro A, Cattalini M, Oggiano S, Fazzi E, et al. Body experiences, emotional competence, and psychosocial functioning in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:2045–52.

Memari AH, Chamanara E, Ziaee V, Kordi R, Raeeskarami SR. Behavioral problems in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a controlled study to examine the risk of psychopathology in a chronic pediatric disorder. Int J Chronic Dis. 2016;2016:5726236.

Oommen PT, Klotsche J, Dressler F, Foeldvari I, Foell D, Horneff G, et al. Frequency of depressive and anxious symptoms in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) – Data from the Inception Cohort of Newly diagnosed patients with JIA (ICON). Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:143.

Tarakci E, Yeldan I, Kaya Mutlu E, Baydogan SN, Kasapcopur O. The relationship between physical activity level, anxiety, depression, and functional ability in children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1415–20.

Fair DC, Nocton JJ, Panepinto JA, Yan K, Zhang J, Rodriguez M, et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in juvenile idiopathic arthritis correlate with pain and stress using PROMIS measures. J Rheumatol. 2022;49:74–80.

Berthold E, Dahlberg A, Jöud A, Tydén H, Månsson B, Kahn F, et al. The risk of depression and anxiety is not increased in individuals with juvenile idiopathic arthritis – results from the south-Swedish juvenile idiopathic arthritis cohort. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2022;20:114.

Sauer K, Barkmann C, Klasen F, Bullinger M, Glaeske G, Ravens-Sieberer U. How often do German children and adolescents show signs of common mental health problems? Results from different methodological approaches-a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:229.

Hanns L, Cordingley L, Galloway J, Norton S, Carvalho LA, Christie D, et al. Depressive symptoms, pain and disability for adolescent patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the childhood arthritis prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57:1381–9.

Sengler C, Milatz F, Minden K. Mental health in children and adolescents with rheumatic diseases. Screening as an integral part of care. Arthritis und Rheuma. 2022;42:381–8.

Albrecht K, Binder S, Minden K, Poddubnyy D, Regierer AC, Strangfeld A, Callhoff J. Systematic review to estimate the prevalence of inflammatory rheumatic diseases in Germany. Z Rheumatol 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-022-01305-2. Online ahead of print.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the BARMER for providing access to data via their data warehouse for this study. We thank the research partners Peter Böhm, Andrea-Dagmar Quiring and Julius Wiegand in the TARISMA project for dedicating their time to add the patient perspective to this project. They have accompanied our research from application to implementation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The study was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research within the research network TARISMA [01EC1902A].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FM, JK, KA, KM and JC conceived the idea for the article. UM and JC were involved in data acquisition. FM, KA, JK, KM and JC designed the study, planned analyses and interpreted the results. JC extracted the data and performed the analyses. FM and KA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and agreed with the submission. JC had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin (EA2/233/22).

Consent for publication

Not required.

Competing interests

JC received speaker fees from Janssen-Cilag GmbH. FM, KA, KM, JK, UM have no conflicts of interest. UM is an employee of the BARMER. There were no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Milatz, F., Albrecht, K., Minden, K. et al. Mental comorbidities in adolescents and young adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: an analysis of German nationwide health insurance data. Pediatr Rheumatol 22, 10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-023-00948-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-023-00948-y