Abstract

Background

Chronic illness, such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), appears to have an impact on the mental health of children and adolescents. The aim of this study was to explore the incidence of mental and behavioural disorders according to age at JIA onset and gender in JIA patients compared to a control population.

Methods

Information on all incident patients with JIA in 2000–2014 was collected from the nationwide register, maintained by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland. The National Population Registry identified three controls (similar regarding age, sex and residence) for each case. They were followed up together until 31st Dec. 2016. ICD-10 codes of their psychiatric diagnoses (F10-F98) were obtained from the Care Register of the National Institute for Health and Welfare. The data were analysed using generalized linear models.

Results

The cumulative incidence of psychiatric morbidity was higher among the JIA patients than the controls, hazard ratio 1.70 (95% Cl 1.57 to 1.74), p < 0.001. Phobic, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, stress-related and somatoform disorders (F40–48) and mood (affective) disorders (F30–39) were the most common psychiatric diagnoses in both the JIA patients (10.4 and 8.2%) and the control group (5.4 and 5.1%), respectively. Female patients were more prone to mental and behavioural disorders than males were, and the risk seemed to be higher in patients who developed JIA in early childhood or adolescence.

Conclusion

Patients with JIA are diagnosed with mental and behavioural disorders more often than controls, and the age at onset of JIA could have implications for future mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a heterogeneous inflammatory rheumatic disease with onset before the age of 16 years. It is classified into seven categories according to the ILAR (International League of Associations for Rheumatology) criteria [1] .

Children and adolescents with JIA are more likely to have psychiatric problems than their healthy counterparts are [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Varying results have been reported, mostly due to differences in study populations (age, disease state/disability, disease duration, medication) and differences in study methods such as self-questionnaires [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], psychiatric interviews [2, 3] or quality of life studies [4, 5, 16,17,18,19,20,21]. Using questionnaires, some studies have found no differences in mental health or psychiatric disorders between patients with JIA and controls [14,15,16,17,18,19,20, 22, 23], whereas other studies have reported significant differences [4,5,6,7].

The most common psychiatric disorders in both JIA patients and the general population are depression and anxiety [2, 3, 24, 25], and most questionnaire-based studies have focused on these disorders [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Only a few have reported increased numbers of behavioural problems in JIA patients [7, 11, 15, 23].

To our knowledge, there are no studies exploring the whole spectrum of clinical mental and behavioural disorders among patients with JIA. Most of previous studies have focused on depression, anxiety and behaviour problems through self-questionnaires and on mental health from a quality of life perspective. In this study, we explored all psychiatric diagnoses in JIA patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2014 and compared their psychiatric morbidity with that of the control population. In our extensive data we also studied the influence of gender and the child’s age at JIA onset on psychiatric morbidity.

Patients and methods

In Finland, patients with certain chronic and severe diseases, such as JIA, are entitled to a special (higher) reimbursement of medication costs from the Social Insurance Institution (SII). From this national reimbursement register, information on all patients with the ICD-10 code of M08.0-M08.9 or M09.0*L40.5 and with the date of first reimbursement decision from 1st Jan. 2000 to 31st Dec. 2014 (index date) were collected. Mild cases of JIA with no need for disease-modifying antirheumatic drug were not included in the SII register. In this study, the index day serves as a surrogate of the day of diagnosis. For each case, the National Population Registry identified three controls individually matched for age, sex and residence at the index date. The individuals were followed up until 31st Dec. 2016. The data were de-identified.

In Finland, municipalities are responsible for organizing health services in their area, including primary health care and hospitals for special outpatient and inpatient care. The Finnish law on the personal registers obligates the service providers to produce information to the Care Register of National Institute for Health and Welfare. The Care Register covers all hospital care in Finland since 1969, and since 1998, secondary care outpatient visits have been included. Information includes personal identification code and diagnoses of the patient’s medical problems as codes of the International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition (ICD-10). Psychiatric diagnoses (ICD-10 codes of F10–98) since the index day were obtained from the Care Register.

Psychiatric diagnoses were grouped into eight main categories (Table 1). Mental retardation (F70–79) was not included in the analysis.

Statistical methods

Cumulative incidence of the first psychiatric diagnoses was based on the product limit estimate (Kaplan-Meier) of cumulative function. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate the psychiatric morbidity risk of the JIA patients and the control population. The results are presented as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The number and incidence were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution. Incidence rate and incidence rate ratios (IRR) were calculated using a Poisson regression model. The Poisson regression was tested using the goodness of fit of the model, and the assumption of overdispersion in the Poisson model was tested using the Lagrange multiplier test. A possible nonlinear relationship between incidences of psychiatric diagnoses and the age at diagnosis were assessed using a 4-knot-restricted cubic spline Poisson regression model. Stata 16.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for the analyses.

Permission to use the databases was obtained from the SII and the National Institute for Health and Welfare. According to Finnish legislation, no ethical committee approval or patients’ informed consent is required for register-based studies done without contacting study subjects.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 4180 JIA patient (2603 females, 1577 males) with the index day during 2000–2014 were identified. The mean age (SD) at the index date was 8.3 (4.8) years. The median follow-up time was 6.6 years (IQR 3.1–10.5). The mean age at the end of follow-up was 14.8 (6.4) years. The patients were compared with 12,512 population controls, matched for age, sex and residence at the index date (7793 females, 4719 males). The total follow-up time was 37,239 person years in JIA patients and 111,684 person years in controls.

Incidence of mental and behavioural disorders

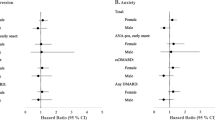

During the follow-up time, 959 (22.9%) JIA patients and 1787 (14.3%) comparators were diagnosed with some mental or behavioural disorder. The risk of developing psychiatric morbidity was higher among the JIA patients, HR 1.70 (95% Cl 1.57 to 1.74), females’ HR 1.83 (1.66 to 2.01), males’ HR 1.49 (1.30 to 1.71). The 10-year cumulative incidence was 25.3% (95% Cl 23.8 to 26.9) in JIA patients and 15.3% (95% Cl 14.6 to 16.0) in controls (Fig. 1).

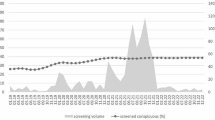

We analysed psychiatric disorder incidence rates in diagnosis groups by gender and age at JIA diagnosis comparing patients with controls. The two most common diagnosis groups were neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (F40–48) and mood disorders (F30–39) both in JIA patients and in controls, and the incidence rate was higher among females (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Childhood behavioural and emotional disorders (F90–98) was the third in frequency. Here the gender difference was minor.

Incidence rate of psychiatric diagnoses in juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients and controls, separated by gender. Incidence rate of psychiatric diagnoses in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) patients and controls according to age in years at JIA onset in eight main psychiatric diagnostic categories (F10-F98), females (A) and males (B). Incidence rate of JIA is indicated with a solid line and incidence rate of controls with a dashed line. Grey area represents 95% confidence intervals

When comparing patients with controls, females with JIA had higher incidence rate ratios than males with JIA, 1.71 (95% Cl 1.55 to 1.88) in females and 1.46 (95% Cl 1.28 to 1.66) in males. In females, IRRs were significantly elevated in all but two small diagnosis groups: mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10–19) and disorders of adult personality and behaviour (F60–69) (Table 2). Among males, IRRs were significantly increased in diagnosis groups of neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (F40–48), behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (F50–59) and childhood behavioural and emotional disorders (F90–98) (Table 2).

The age at which children were diagnosed with JIA was associated with incidence of mental and behavioural disorders. Incidence rate of behavioural disorders was highest among children who developed JIA in early childhood, whereas rates of neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders and mood disorders were highest among girls who developed JIA in adolescence (Fig. 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale longitudinal register-based study covering all mental and behavioural disorders in patients with JIA and the impact of the age at JIA onset on those disorders. We found that incident patients with JIA had a higher risk of mental and behavioural disorders than did the control population. The three most common disorders were neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (F40–48); mood disorders (F30–39); and childhood behavioural and emotional disorders (F90–98). Some studies from recent years have reported results of same kind. Two cross-sectional questionnaire studies reported a higher incidence of behavioural problems, anxiety and depression in children and adolescent JIA patients compared to controls [6, 7]. More frequent psychiatric morbidity in patients with JIA was also observed in two small studies based on clinical assessment [2, 3]. However, some questionnaire studies did not show a difference in anxiety and depression between patients and controls [14,15,16,17,18,19,20, 22, 23].

We found that those who developed JIA in early childhood tended to have higher rates of behavioural disorders compared to controls than did those who were diagnosed with JIA in later years. In addition, anxiety and depression rates seemed to be higher in those patients with disease onset in adolescence than in those with onset in childhood (Fig. 2). According to psychological development theories, the onset of a chronic disease upsets the balance of mind and body [26], and the reaction to the traumatic experience depends on the age of the child [8, 26,27,28]. Children under the age of 7 years have limited ego functions, and they tend to react by expressing rage and aggression [11, 26], but by the primary school age, children have developed strategies to better handle emotional situations [26]. In adolescence, diagnosis of a chronic disease along with the normal personality development, bodily changes and goals for independence can give rise to anxiety, phobias and obsessive-compulsive disorders [11, 26, 29]. In addition, children and adolescents with JIA who have a reduced psychological maturity may also have a lower self-esteem and more anxiety and depression traits compared to healthy children and adolescents [6]. In other words, good self-efficacy and self-esteem can protect against psychological problems related to JIA in childhood and adolescence [10, 15].

In our study, the incidence rate of neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders and mood disorders seemed to be higher among females who developed JIA in adolescence (Fig. 2). Some previous studies have reported similar findings for depression and anxiety. A prospective clinical study of newly diagnosed JIA patients from 11 to 16 years of age showed significantly higher depression symptom scores in females than in males [12]. Another questionnaire study found that females with JIA (8–16 years) tended to have higher scores of anxiety and depression than did males [9]. However, a meta-analysis about behavioural problems in chronically ill children and adolescents including those with JIA showed male preponderance [30]. Males with JIA may respond to their illness with behavioural symptoms because such a behaviour is more natural for boys than girls [21, 30, 31]. Gender difference in anxiety, depression and behavioural disorders have also been observed in the general population [32].

Our study has many strengths. It covers the whole population and explores a wide spectrum of psychiatric diagnoses in all newly onset JIA patients between 2000 and 2014 compared to their population controls. The Care Register of the National Institute for Health and Welfare is systematically quality controlled [33]. Logical errors are algorithmically checked, and detected errors are sent to hospitals for correction [33]. According to a quality report, the completeness of the register was found to be very good [33].

This study does not cover mild mental health problems, which are not referred to specialized care. In addition, register study may have left out healthy controls that are less sensitive to seek health services than JIA patients with a regular contact with health care. Therefore, mental health problems might not arise either. Parental concern about the child’s active disease can also lead to increased use of mental health services in JIA patients too. All of the above may cause bias when comparing psychiatric morbidity between patients and controls. The follow-up time might not have been long enough for very young JIA patients from recent years to have time to receive a psychiatric diagnosis.

Through our research, we have received new information about the age at JIA onset and gender influence on psychiatric morbidity.

Conclusion

In summary, patients with JIA have psychiatric diagnoses more frequently than do controls, especially female patients. Age at onset of JIA might affect the risk of psychiatric illness.

Availability of data and materials

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- JIA:

-

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- ICD-10:

-

Codes of the International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition

- ILAR:

-

International League of Associations for Rheumatology

- SII:

-

The Social Insurance Institution

- DMARD:

-

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drug

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- Cl:

-

Confidence interval

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- IRR:

-

Incidence rate ratio

References

Giancane G, Consolaro A, Lanni S, Davì S, Schiappapietra B, Ravelli A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: diagnosis and treatment. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3(2):187–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-016-0040-4.

Vandvik IH. Mental health and psychosocial functioning in children with recent onset of rheumatic disease. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1990;31(6):961–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb00837.x.

Mullick MS, Nahar JS, Haq SA. Psychiatric morbidity, stressors, impact, and burden in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Health Popul Nutr. 2005;23(2):142–9.

Flato B, Lien G, Smerdel A, Vinje O, Dale K, Johnston V, et al. Prognostic factors in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study revealing early predictors and outcome after 14.9 years. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(2):386–93.

Barth S, Haas JP, Schlichtiger J, Molz J, Bisdorff B, Michels H, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life in German patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in comparison to German general population. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153267. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153267.

Bomba M, Meini A, Molinaro A, Cattalini M, Oggiano S, Fazzi E, et al. Body experiences, emotional competence, and psychosocial functioning in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(8):2045–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-013-2685-4.

Memari AH, Chamanara E, Ziaee V, Kordi R, Raeeskarami SR. Behavioral problems in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a controlled study to examine the risk of psychopathology in a chronic pediatric disorder. Int J Chronic Dis. 2016;2016:5726236.

Packham JC, Hall MA. Long-term follow-up of 246 adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: education and employment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41(12):1436–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/41.12.1436.

Margetic B, Aukst-Margetic B, Bilic E, Jelusic M, Tambic BL. Depression, anxiety and pain in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(3):274–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.12.014.

Vuorimaa H, Tamm K, Honkanen V, Konttinen YT, Komulainen E, Santavirta N. Empirical classification of children with JIA: a multidimensional approach to pain and well-being. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(5):954–61.

Russo E, Trevisi E, Zulian F, Battaglia MA, Viel D, Facchin D, et al. Psychological profile in children and adolescents with severe course juvenile idiopathic arthritis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:841375.

Hanns L, Cordingley L, Galloway J, Norton S, Carvalho LA, Christie D, et al. Depressive symptoms, pain and disability for adolescent patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from the childhood arthritis prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(8):1381–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key088.

Stevanovic D, Susic G. Health-related quality of life and emotional problems in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(3):607–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0172-0.

Tarakci E, Yeldan I, Kaya Mutlu E, Baydogan SN, Kasapcopur O. The relationship between physical activity level, anxiety, depression, and functional ability in children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(11):1415–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-011-1832-0.

Huygen AC, Kuis W, Sinnema G. Psychological, behavioural, and social adjustment in children and adolescents with juvenile chronic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(4):276–82. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.59.4.276.

Peterson LS, Mason T, Nelson AM, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Psychosocial outcomes and health status of adults who have had juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a controlled, population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(12):2235–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780401219.

Foster HE, Marshall N, Myers A, Dunkley P, Griffiths ID. Outcome in adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a quality of life study. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(3):767–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.10863.

Arkela-Kautiainen M, Haapasaari J, Kautiainen H, Vilkkumaa I, Malkia E, Leirisalo-Repo M. Favourable social functioning and health related quality of life of patients with JIA in early adulthood. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(6):875–80. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2004.026591.

Oliveira S, Ravelli A, Pistorio A, Castell E, Malattia C, Prieur AM, et al. Proxy-reported health-related quality of life of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the pediatric rheumatology international trials organization multinational quality of life cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):35–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22473.

Ostile IL, Johansson I, Aasland A, Flatö B, Möller A. Self-rated physical and psychosocial health in a cohort of young adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2010;39(4):318–25. https://doi.org/10.3109/03009740903505213.

Ostlie IL, Aasland A, Johansson I, Flatö B, Möller A. A longitudinal follow-up study of physical and psychosocial health in young adults with chronic childhood arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(6):1039–46.

Tollisen A, Selvaag AM, Aulie HA, Lilleby V, Aasland A, Lerdal A, et al. Physical functioning, pain and health-related quality of life in adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a longitudinal 30-year follow-up study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018,70(5):741-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr23327. Epub 2018 Mar 7.

Ding T, Hall A, Jacobs K, David J. Psychological functioning of children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis is related to physical disability but not to disease status. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):660–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ken095.

Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC. Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(1):7–20.

Paananen R, Ristikari T, Merikukka M, Gissler M. Social determinants of mental health: a Finnish nationwide follow-up study on mental disorders. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(12):1025–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-202768.

D'Alberton F, Nardi I, Zucchini S. The onset of chronic disease as a traumatic psychic experience: a psychodynamic survey on a type 1 diabetes in young patients. Psychoanal Psychother. 2012;26(4):294–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2012.732103.

Packham JC. Overview of the psychosocial concerns of young adults with juvenile arthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2004;2(1):6–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.52.

Turkel S, Pao M. Late consequences of chronic pediatric illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(4):819–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2007.07.009.

Cohen P, Pine DS, Must A, Kasen S, Brook J. Prospective associations between somatic illness and mental illness from childhood to adulthood. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(3):232–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009442.

Pinquart M, Shen Y. Behavior problems in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(9):1003–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsr042.

Suris JC, Michaud PA, Viner R. The adolescent with a chronic condition. Part I: developmental issues. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(10):938–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2003.045369.

Hankin BL, Young JF, Abela JR, Smolen A, Jenness JL, Gulley LD, et al. Depression from childhood into late adolescence: influence of gender, development, genetic susceptibility, and peer stress. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015;124(4):803–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000089.

Sund R. Quality of the Finnish hospital discharge register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(6):505–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812456637.

Acknowledgements

Not applicaple.

Funding

This work was supported by the Finnish Cultural Foundation; the Finnish Pediatric Research Foundation; the Alma and K. A. Snellman Foundation, Oulu, Finland; and the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MSK, HK, KP and PV have made a significant contribution to the design of the work. MSK was a major contributor in writing the manuscript, PV, HE and KP were co-authors of this manuscript and HK analysed the data, performed statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Permission to use the databases was obtained from the SII and the National Institute for Health and Welfare. According to Finnish legislation, no ethical committee approval or patients’ informed consent is required for register-based studies done without contacting study subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kyllönen, M.S., Ebeling, H., Kautiainen, H. et al. Psychiatric disorders in incident patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis - a case-control cohort study. Pediatr Rheumatol 19, 105 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-021-00599-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-021-00599-x