Abstract

Background

Understanding the underlying mechanism of thrombus formation and its components is critical for effective prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke. The generation of thrombotic clots requires conversion of soluble fibrinogen to an insoluble fibrin network. Quantitative features of intracranial clots causing acute ischemic stroke can be studied on non-contrast enhanced CT (NECT). Here, we evaluated on-admission fibrinogen and clot burden in relation to stroke severity, final infarct volume and in-hospital mortality.

Methods

We included 132 consecutive patients with ischemic stroke and presence of hyperdense artery sign admitted within 6 h from symptom onset. Radiological parameters including clot area (corresponding to clot burden) and final infarct volume were manually determined on NECT. National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was used to quantify disease severity and short-term outcome.

Results

Median patient age was 77, 58 % were women, and 63 % had an occlusion of the proximal middle cerebral artery segment. Thrombolysis was performed in 60 % and thrombectomy in 44 %. We identified several independent associations. Higher fibrinogen levels on admission were associated with smaller clot burden (p = 0.033) and lower NIHSS on admission (p = 0.022). Patients with lower fibrinogen had a higher clot burden (p = 0.028) and greater final infarct volume (p = 0.003). Higher fibrinogen was associated with a lower risk of in-hospital death or NIHSS score >15 if discharged alive (p = 0.028).

Conclusions

Our study suggests that intracranial clot burden in acute ischemic stroke is associated with fibrinogen consumption, and shows a complex relationship with disease severity, infarct size and in-hospital survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cerebral blood flow can be interrupted by occlusion of major intracranial arteries and result in acute ischemic stroke [1]. Fibrinogen is a glycoprotein that helps in the formation of occluding blood clots. Fibrin, the product of thrombin’s proteolytic cleavage of fibrinogen, provides its biophysical and biochemical support [2]. Arterial thrombi are essentially composed of platelets with fibrin, whereas venous thrombi are rich of red-blood cells [3, 4]. Tissue-plasminogen activator (t-PA) is an thrombolytic agent for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke which dissolves fibrin bonds in the clot by activating plasminogen and is approved for iv treatment up to 4.5 h from symptom onset [5].

Several large prospective studied identified high fibrinogen plasma levels as an independent predictor of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke [6–8]. While elevated fibrinogen is associated with other cardiovascular risk factors including age, smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol, the relationship with stroke persisted even after correcting for these confounders [9]. Most recently, Potpara and coworkers identified the association of plasma fibrinogen with poor functional 30-day outcome in ischemic stroke [10]. Liu and coworkers studied fibrinogen levels in different stroke etiologies stratified according to the Trial of Org 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification [11]. While fibrinogen levels did not differ among the stroke subtypes, elevated d-dimer levels, a specific fibrinolysis marker, were typical for cardioembolic etiology.

Response to t-PA therapy and also efficacy of thrombectomy varies and presumably depends on a wide range of variables including location, time frame and radiological characteristics such as width, length and structure [12]. To this end, qualitative clot characteristics can be assessed on non-contrast enhanced CT (NECT). Fibrin is loosely packed in thrombi of cardioembolic origin and has better chances of recanalization using t-PA [4, 13]. Thrombi derived from large artery arteriosclerosis (LAA) comprise densely packed fibrin and are less likely to be resolved by medical strategies aimed at dissolving fibrin bonds.

An acute lowering of fibrinogen can be caused by degradation due to hyperreactive or stimulated systemic coagulation, resulting in increased thrombin formation and platelet activation [14]. Such rapid alterations of fibrinogen levels in the peripheral circulation are associated with clot burden in various acute thrombotic conditions. Fibrinogen consumption and a relationship with thrombin production has been reported for acute myocardial infarction, whereas this was not the case for stable coronary artery disease [15]. Notably, fibrinogen consumption is associated with a larger clot burden in pulmonary embolism [16]. Thus, it seems likely that fibrinogen degradation takes place in acute ischemic stroke caused by thrombotic occlusion of intracranial arteries. Here, we aimed to investigate the relationship between on-admission fibrinogen levels and radiological clot burden quantified within the first 6 h from symptom onset in acute ischemic stroke in relation with early clinical and radiological markers of outcome.

Methods

Study design

We reviewed medical records of consecutive patients admitted to the Christian Doppler Medical Center with acute ischemic stroke. The study period was January 2013 to January 2015. During the entire study period, there was no change of leading stroke staff, all three senior physicians were full-time neurologists.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) age ≥18 years; (b) diagnosis of ischemic stroke; (c) proven intracranial vessel occlusion with quantifiable clot dimensions within 6 h after stroke onset (Fig. 1a); (d) presence of a hyperdense artery which was defined as “spontaneous visibility of complete or a part of” intracranial artery in segments with no calcifications [17]. We excluded cases without a hyperdense artery sign or non-ischemic intracerebral pathology was detected. For the purpose of group comparison we compiled a “non-MCA” group, which concerned all intracranial vessels other than branches of the middle cerebral artery.

Study design. a Screening and inclusion of patients in the present analysis. b Diagram of the planned successive hypotheses about relationship between on-admission fibrinogen and imaging and clinical findings. Full arrows indicate direct associations and dotted arrows indicate the assumed indirect (mediated “through” mediator variables) associations. CTA angiography by computed tomography, DSA digital subtraction angiography, MRA angiography by magnetic resonance, NECT non-enhanced computed tomography, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, rt-PA recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

Ethics section

The protocol was in accordance with the ethical standards of our hospital’s committee for the protection of human subjects (protocol UN 2553). According to Austrian regulations, individualized informed consent is not required for routinely collected clinical and radiologic data as used in this study.

Institutional standard procedure with acute stroke patients

Patients were treated according to the national stroke guidelines and local standard operation procedures for neuroimaging and mechanical thrombectomy. Minimal diagnostic work-up procedures included laboratory examinations on admission, extracranial Doppler und Duplex sonography of the brain-supplying arteries, monitoring at the stroke unit, extracranial transthoracic echocardiography, 24-h ECG monitoring and follow-up CT within 7 days. In-hospital variables were collected retrospectively for all patients via medical chart review and the IMPAX system (AGFA Healthcare, Mortsel, Belgium). Clinical disability on admission and transfer were routinely recorded with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) by certified physicians.

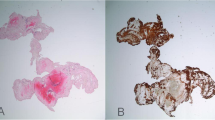

Quantification of the clot burden

NECT and CT angiography scans were performed in a multidetector CT scanner Sensation 64 (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The NECT scans were reconstructed into 4 mm thick adjacent slices through the entire brain. Two experienced neurologists blinded to the clinical information independently reviewed rated the scans. In case of disagreement, they discussed until a consensus was reached. The clot area was measured by delineating the hyperdense artery on NECT that corresponded to occlusion site on CT-A/MR-A/conventional angiography and/or matched with final infarct area. The region of interest was drawn around the hyperdense part of the artery and the area was automatically calculated using IMPAX software. When hyperdense artery area was seen on more than one slice the measured areas were summed [12]. In this regard, we used “clot area” (in mm2) as a measure of clot burden.

Quantification of the final infarct volume

The follow-up CT scans were examined for infarct demarcation. The infarct area was manually delineated on each CT slice (4 mm height) which yielded area in cm2. Finally, the volume in cm3 was summed from the measured area and the corresponding slice thickness [18].

Data analysis

Data analysis was conceived as a set of regressions aimed to test consecutive hypotheses about associations (“effects” used in the meaning of regression analysis, not necessarily implying causal relationship) between on-admission fibrinogen levels and co-incident or subsequent imaging and clinical findings (Fig. 1b). The analysis was driven by temporal and pathophysiological rationales: (a) the first step tested the association between on-admission fibrinogen and clot area (representing clot burden); (b) the next step tested the association between on-admission fibrinogen and clot area (simultaneously and separately) with NIHSS score at presentation. Differences in the strength of simultaneous and separate independent associations were to be considered an indication of possible direct and mediated (through the “effect” on clot area) “effects” of on-admission fibrinogen. In the same way, (c) the third step tested the association between on-admission fibrinogen and/or clot area and the final infarct volume; (d) the final step, following this concept, tested the association between on-admission fibrinogen and in-hospital clinical outcomes, accounting (simultaneously or separately) for clot area, final infarct volume and disease severity at presentation. For this purpose, a composite outcome of in-hospital death or survival but with NIHSS score >15 at discharge (moderate/severe or severe stroke) was analyzed. Continuous outcomes (clot area, infarct volume, NIHSS scores) were analyzed by fitting general linear models, whereas the composite of in-hospital mortality/NIHSS score at discharge >15 was analyzed by fitting modified Poisson regressions with robust error variance [19] to yield relative risks. Where required for achievement of normality of residuals, dependent and/or independent continuous variables were ln-transformed. All analyses were performed in SAS 9.3 for Windows (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics and their relationship to on-admission fibrinogen levels

A total of 132 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Most hyperdense artery signs could be confirmed by the performance of a CT-A (84.1 %) (Fig. 1a). Demographics and further characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1.

On-admission fibrinogen ranged between 3.1 and 24.3 μmol/L and higher values were independently associated with older age (p = 0.002), higher C-reactive protein (p < 0.001), history of diabetes (p = 0.038) and history of heart failure (p = 0.020) (see Additional file 1: Table S1).

Relationship between on-admission fibrinogen levels and clot area (clot burden)

Clot area ranged from 2.5 to 211 mm2 (Table 1). With adjustment for sex, history of carotid stenosis >50 % and type of the affected vessel (the only covariates with multivariate p < 0.1), higher on-admission fibrinogen was independently associated with a lower clot area (Table 2).

Relationship between on-admission fibrinogen levels, clot area (clot burden) and severity of symptoms at presentation

NIHSS scores at presentation ranged from 0 to 32 points (Table 1). With adjustment for time elapsed since symptom onset to imaging, age, C-reactive protein and serum glucose levels, type of the affected vessel and clot area (the only covariates with multivariate p < 0.1) higher on-admission fibrinogen was independently associated with lower NIHSS scores (Table 3, Model 1). Higher clot area was associated with higher NIHSS scores but with borderline statistical significance when fibrinogen was in the model (p = 0.054; Table 3, Model 1). In separate models (with all other effects) including either fibrinogen (Table 3, Model 2) or clot area (Table 3, Model 3), each were independently associated with more severe symptoms at presentation. Following independent associations were evaluated: on-admission fibrinogen—clot area; on-admission fibrinogen—symptom severity at presentation; clot area—symptom severity at presentation, attenuation of “effects” of fibrinogen and clot area on symptom severity when both were accounted for the assumption that the “effect” of on-admission fibrinogen on symptom severity is at least in part mediated through its “effect” on the clot area (Fig. 2).

Relationship between on-admission fibrinogen, type of the affected vessel, clot area (clot burden) and final infarct volume. a On-admission fibrinogen (μmol/L) (upper panel), clot areas (mm2) (middle panel) and final infarct volumes (mm3) according to the type of the affected vessel. Dots are individual values, horizontal lines are medians (numerical values depicted), boxes indicate upper and lower quartiles and bars are inner fences [median ± (1.5 × interquartile range)]. Values outside fences are outliers. b Fitted (adjusted) regression of ln(infarct volume) on ln(clot area) by vessel type, from the model depicted in Table 4 in the main text. MCA middle cerebral artery

Relationship between on-admission fibrinogen, clot burden and final infarct volume

The relationship between on-admission fibrinogen, clot area and final infarct volume appeared complex and conditional on the affected vessel (Fig. 1 depicts individual values by type of the affected vessel). With adjustment for C-reactive protein and glucose levels, performed thrombectomy [options: not done, done but inadequate perfusion (TICI grade 0–2a) or adequate (TICI grade 2b–3)] and type of the affected vessel (the only covariates with multivariate p < 0.1), higher on-admission fibrinogen was independently associated with a lower infarct volume (Table 4). In contrast, larger clot area was associated with a higher infarct volume, but only in the case of proximal MCA (p = 0.069 for the clot area*vessel type interaction) (Table 4) [Fig. 2 depicts adjusted regressions of ln(infarct volume) on ln(clot area) by vessel type]. The association between on-admission fibrinogen and infarct volume was unchanged when the clot area was removed, and the association between clot area and infarct volume remained unchanged when fibrinogen was removed from the model (not shown).

Relationship between on-admission fibrinogen, clot burden, symptom severity at presentation, final infarct volume and clinical outcomes—in-hospital mortality and symptom severity in hospital survivors

A total of 26 patients (19.7 %) died during the hospital stay (Table 1). NIHSS score at discharge in survivors (n = 106) varied between 0 and 30 (Table 1) and was >15 (moderate/severe or severe stroke) in 27 (25.5 %) of them. Overall, 53 (40.2 %) patients either died in hospital or were discharged with NIHSS score >15.

We found that higher on-admission fibrinogen was associated with a lower risk of in-hospital death/NIHSS score at discharge >15 (Table 5, Model 1). This was confirmed after adjustment for age, sex, time since symptom onset to imaging, C-reactive protein and glucose levels and type of the affected vessel (covariates found independently associated with on-admission fibrinogen or clot area or final infarct volume or NIHSS score at presentation, Tables 1, 2, 3, 4), and thrombectomy.

With the same adjustments, higher clot area (Table 5, Model 2), larger infarct volume (Table 5, Model 3) and higher NIHSS at presentation (Table 5, Model 4) were each associated with a higher risk of in-hospital death/NIHSS score at discharge >15.

In a full model (Table 5, Model 5), i.e., with all “default adjustments” and including fibrinogen, clot area, infarct volume and NIHSS at presentation—only higher NIHSS at presentation (p < 0.001) remained independently associated with an increased risk.

The sequence of independent associations between on-admission fibrinogen and clot area, fibrinogen and clot area with NIHSS score at presentation, fibrinogen and clot area with final infarct volume and associations depicted in Table 5. Together with the attenuation of the “effects” of on-admission fibrinogen, clot area and infarct volume on the clinical outcome when all (together with NIHSS at presentation) were in the same model, implicates that the association between on-admission fibrinogen and assessed clinical outcomes is mediated through its association with clot area, infarct volume and severity of disease at presentation.

Discussion

Understanding the underlying mechanism of thrombus formation and its consequences is critical for effective prevention and treatment of ischemic stroke. This study disclosed an independent inverse relation between on-admission fibrinogen levels and clot burden. This finding points at in vivo fibrinogen consumption in and after the process of thrombus formation. Moreover, fibrinogen degradation and clot size showed a complex relationship with disease severity, infarct size and in-hospital survival.

Fibrinogen is a central molecule in thrombosis and hemostasis and implicated in additional conditions including as well as in pathologies including inflammation, host defense, cancer, and neuropathology. Indeed, elevated fibrinogen is one of the most prevalent risk factors for thrombotic disorders [20–22]. We corroborate the reported independent associations between higher on-admission fibrinogen levels and older age, higher C-reactive protein, diabetes and history of cardiovascular disease in acute ischemic stroke patients. Moreover, higher clot burden is associated with more severe stroke symptoms at presentation [18, 19]. We expand these observations on the basis of our second analysis step by reporting an independent association between lower fibrinogen and more severe presenting symptoms, and between higher clot burden and disease severity. In the full model (Table 3) both associations weakened, and the latter one reached “only” a borderline statistical significance. Since the first-step analysis demonstrated the association between the two, this phenomenon was expected and indicated that, at least in part, the “link” between on-admission fibrinogen levels and symptoms at presentation “went through” its effect on the clot burden. Moreover, the fact that the strength of association between fibrinogen levels and symptom severity was less reduced than the strength of association between the clot burden and symptom severity suggests that fibrinogen might reflect clot perturbations on a finer scale (thrombus formation/lysis) and therefore could be a better indicator of the extent of thrombus, while clot burden measurement is essentially flawed by imperfect methodology. We propose that NECT depicts only a part or only the erythrocyte-rich part of the thrombus whilst the platelet and/or fibrin-rich (and thus hypoattenuating) parts are not visible on NECT. It also needs to be taken into account that intracranial clots are not homogenous and ongoing apposition and endogenous thrombolysis takes place [23, 24]. This assumption is backed by findings in ischemic heart disease, where proximal and distal of the fibrin-thrombocyte rich nidus develop after the local plaque rupture in coronary vessels [25]. Local hemodynamics and collaterals may also contribute to qualitative and quantitative alterations of the clot [23, 26].

The final infarct volume is a consequence of a multitude of factors or their combinations, such as the presence of collaterals or the choice of treatment, and could serve as the stroke outcome surrogate [27]. At the third step, the present analysis indicated that both on-admission fibrinogen (inversely) and clot burden were independently associated with the final infarct volume. However, the latter association was conditional on the type of the affected vessel—it was only relevant in occlusion of the middle cerebral artery.

Finally, the most complex relationship observed was the relation of on-admission fibrinogen and poor in-hospital outcome (death or NIHSS score at discharge >15). This points at an independent association between higher fibrinogen and a reduced risk—but not when “intermediate” outcomes (clot area, final infarct volume, symptom severity at presentation) to which fibrinogen was also related, were accounted for, suggesting that the “effect” of fibrinogen was conveyed “through” these mediators. Although such a sequence of events appears mechanistically plausible, the present observations should be taken with a caution since we considered only the on-admission fibrinogen levels. Fibrinogen levels steadily rise over 120 h after stroke, are linked to a poor outcome and are decreases with t-PA treatment and subsequently raise risk for intracranial hemorrhage [28, 29]. Of note, Sun and coworkers found that the decrease in fibrinogen less than 2 g/L multiplies the odds of early parenchymal hemorrhage as a complication of intravenous thrombolysis by factor 12.8 [30].

The present study has a several limitations, which need to be considered in future studies. The retrospective studies might have introduced bias and we did not assess plasma levels of tissue plasminogen activator or plasmin activator inhibitor-1 as well as fibrinogen degradation products. The major limitation to generalizability, however, arises from the fact that we studied only patients with hyperdense artery signs. Up to 70 % of occlusive thrombi on NECT are hyperdense, but there are patients with the major vessel occlusion without a hyperdense artery and they were not present in our study. Additionally, small vessel occlusion i.e. lacunar strokes were not included as clot area measurement in non-hyperdense thrombi is not plausible. Overall, while we used a timely methodology, we admit that smaller hyperdense signs may have been missed. On the other hand, the study has several strengths—all patients underwent standardized diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, medical history data were complete, all radiological assessments were done after pre-defined criteria by raters blinded to clinical outcomes and data were viewed in a sensible and thorough way.

Conclusion

We investigated the relationship between on-admission fibrinogen levels and clot burden, symptom severity at presentation, and in-hospital clinical and radiological outcomes in a moderately sized sample of highly selective stroke patients with the sign of acute vessel occlusion within the first 6 h after the stroke onset. Importantly, plasma fibrinogen could predict the majority of clinical and radiological outcomes. The results are novel and provide an important impulse to further unravel dysregulation of coagulation pathways in acute ischemic stroke.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- NECT:

-

non-contrast enhanced CT

- NIHSS:

-

National Institute of Health Stroke Scale

- TOAST:

-

Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment

- t-PA:

-

tissue-plasminogen activator

- CT-A:

-

computed tomography-angiography

- MR-A:

-

magnetic resonance imaging-angiography

- TICI:

-

thrombolysis in cerebral infarction

References

Silva GS, Koroshetz WJ, Gilberto González RG, Schwamm LH. Causes of ischemic stroke. In: González RG, Hirsch JA, Lev MH, Schaefer PW, Schwamm LH, editors. Acute ischemic stroke—imaging and intervention. Berlin: Springer; 2011. p. 25–42.

Wolberg AS. Determinants of fibrin formation, structure, and function. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19:349–56.

Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, Coffey CS, Hoh BL, Jauch EC, Johnston KC, Johnston SC, Khalessi AA, Kidwell CS, et al. AHA/ASA focused update of the 2013 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke regarding endovascular treatment: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46:3020–35.

Sato Y, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Iwakiri T, Ikeda Y, Matsuyama T, Hatakeyama K, Asada Y. Thrombus components in cardioembolic and atherothrombotic strokes. Thromb Res. 2012;130:278–80.

Kirmani JF, Alkawi A, Panezai S, Gizzi M. Advances in thrombolytics for treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2012;79:S119–25.

Eidelman RS, Hennekens CH. Fibrinogen: a predictor of stroke and marker of atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:499–500.

Siegerink B, Rosendaal FR, Algra A. Genetic variation in fibrinogen; its relationship to fibrinogen levels and the risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:385–90.

Chuang SY, Bai CH, Chen WH, Lien LM, Pan WH. Fibrinogen independently predicts the development of ischemic stroke in a Taiwanese population: CVDFACTS study. Stroke. 2009;40:1578–84.

Fibrinogen Studies C, Danesh J, Lewington S, Thompson SG, Lowe GD, Collins R, Kostis JB, Wilson AC, Folsom AR, Wu K, et al. Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;294:1799–809.

Potpara TS, Polovina MM, Djikic D, Marinkovic JM, Kocev N, Lip GY. The association of CHA2DS2-VASc score and blood biomarkers with ischemic stroke outcomes: the Belgrade stroke study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106439.

Liu LB, Li M, Zhuo WY, Zhang YS, Xu AD. The role of hs-CRP, d-dimer and fibrinogen in differentiating etiological subtypes of ischemic stroke. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118301.

Moftakhar P, English JD, Cooke DL, Kim WT, Stout C, Smith WS, Dowd CF, Higashida RT, Halbach VV, Hetts SW. Density of thrombus on admission CT predicts revascularization efficacy in large vessel occlusion acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:243–5.

Puig J, Pedraza S, Demchuk A, Daunis IEJ, Termes H, Blasco G, Soria G, Boada I, Remollo S, Banos J, et al. Quantification of thrombus hounsfield units on noncontrast CT predicts stroke subtype and early recanalization after intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:90–6.

Moresco RN, Vargas LC, Voegeli CF, Santos RC. d-dimer and its relationship to fibrinogen/fibrin degradation products (FDPs) in disorders associated with activation of coagulation or fibrinolytic systems. J Clin Lab Anal. 2003;17:77–9.

Undas A, Szuldrzynski K, Brummel-Ziedins KE, Tracz W, Zmudka K, Mann KG. Systemic blood coagulation activation in acute coronary syndromes. Blood. 2009;113:2070–8.

Kucher N, Kohler HP, Dornhofer T, Wallmann D, Lammle B. Accuracy of d-dimer/fibrinogen ratio to predict pulmonary embolism: a prospective diagnostic study. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:708–13.

Topcuoglu MA, Arsava EM, Akpinar E. Clot characteristics on computed tomography and response to thrombolysis in acute middle cerebral artery stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:1363–72.

Brott T, Marler JR, Olinger CP, Adams HP Jr, Tomsick T, Barsan WG, Biller J, Eberle R, Hertzberg V, Walker M. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: lesion size by computed tomography. Stroke. 1989;20:871–5.

McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:940–3.

Sechi LA, Zingaro L, Catena C, De Marchi S. Increased fibrinogen levels and hemostatic abnormalities in patients with arteriolar nephrosclerosis: association with cardiovascular events. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84:565–70.

Wong LY, Leung RY, Ong KL, Cheung BM. Plasma levels of fibrinogen and C-reactive protein are related to interleukin-6 gene −572C>G polymorphism in subjects with and without hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:875–82.

Stec JJ, Silbershatz H, Tofler GH, Matheney TH, Sutherland P, Lipinska I, Massaro JM, Wilson PF, Muller JE, D’Agostino RB Sr. Association of fibrinogen with cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Population. Circulation. 2000;102:1634–8.

Marder VJ, Chute DJ, Starkman S, Abolian AM, Kidwell C, Liebeskind D, Ovbiagele B, Vinuela F, Duckwiler G, Jahan R, et al. Analysis of thrombi retrieved from cerebral arteries of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:2086–93.

Okafor ON, Gorog DA. Endogenous fibrinolysis: an important mediator of thrombus formation and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1683–99.

Jang IK, Gold HK, Ziskind AA, Fallon JT, Holt RE, Leinbach RC, May JW, Collen D. Differential sensitivity of erythrocyte-rich and platelet-rich arterial thrombi to lysis with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator. A possible explanation for resistance to coronary thrombolysis. Circulation. 1989;79:920–8.

Qazi EM, Sohn SI, Mishra S, Almekhlafi MA, Eesa M, d’Esterre CD, Qazi AA, Puig J, Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK. Thrombus characteristics are related to collaterals and angioarchitecture in acute stroke. Can J Neurol Sci. 2015;42:381–8.

van der Worp HB, Claus SP, Bar PR, Ramos LM, Algra A, van Gijn J, Kappelle LJ. Reproducibility of measurements of cerebral infarct volume on CT scans. Stroke. 2001;32:424–30.

del Zoppo GJ, Levy DE, Wasiewski WW, Pancioli AM, Demchuk AM, Trammel J, Demaerschalk BM, Kaste M, Albers GW, Ringelstein EB. Hyperfibrinogenemia and functional outcome from acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:1687–91.

Matosevic B, Knoflach M, Werner P, Pechlaner R, Zangerle A, Ruecker M, Kirchmayr M, Willeit J, Kiechl S. Fibrinogen degradation coagulopathy and bleeding complications after stroke thrombolysis. Neurology. 2013;80:1216–24.

Sun X, Berthiller J, Trouillas P, Derex L, Diallo L, Hanss M. Early fibrinogen degradation coagulopathy: a predictive factor of parenchymal hematomas in cerebral rt-PA thrombolysis. J Neurol Sci. 2015;351:109–14.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content: SP, VT, SP. Given final approval of the version to be published: all authors. Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: SP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the stroke team at the Christian Doppler Medical Center.

Competing interests

SP none, BT none, MRM, none, JSM received speakers honoraria from Bayer, Genzyme, Boehringer Ingelheim and Ever-Neuropharma. PG none. JS received speakers honoraria from Biogen, Genzyme, Teva-Ratiopharm, Novartis and Ever-Neuropharma.

Availability of data and supporting materials

MRI data can be shared on request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

12967_2016_1006_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Table S1. Baseline patient characteristics associated with on-admission fibrinogen levels: summary of multivariate analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pikija, S., Trkulja, V., Mutzenbach, J.S. et al. Fibrinogen consumption is related to intracranial clot burden in acute ischemic stroke: a retrospective hyperdense artery study. J Transl Med 14, 250 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-016-1006-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-016-1006-6