Abstract

Background

Existing physical activity guidelines predominantly focus on healthy age-stratified target groups. The objective of this study was to develop evidence-based recommendations for physical activity (PA) and PA promotion for German adults (18–65 years) with noncommunicable diseases (NCDs).

Methods

The PA recommendations were developed based on existing PA recommendations. In phase 1, systematic literature searches were conducted for current PA recommendations for seven chronic conditions (osteoarthrosis of the hip and knee, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stable ischemic heart disease, stroke, clinical depression, and chronic non-specific back pain). In phase 2, the PA recommendations were evaluated on the basis of 28 quality criteria, and high-quality recommendations were analysed. In phase 3, PA recommendations for seven chronic conditions were deducted and then synthesised to generate generic German PA recommendations for adults with NCDs. In relation to the recommendations for PA promotion, a systematic literature review was conducted on papers that reviewed the efficacy/effectiveness of interventions for PA promotion in adults with NCDs.

Results

The German recommendations for physical activity state that adults with NCDs should, over the course of a week, do at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic PA, or 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic PA, or a combination of both. Furthermore, muscle-strengthening activities should be performed at least twice a week. The promotion of PA among adults with NCDs should be theory-based, specifically target PA behaviour, and be tailored to the respective target group. In this context, and as an intervention method, exercise referral schemes are one of the more promising methods of promoting PA in adults with NCDs.

Conclusion

The development of evidence-based recommendations for PA and PA promotion is an important step in terms of the initiation and implementation of actions for PA-related health promotion in Germany. The German recommendations for PA and PA promotion inform adults affected by NCDs and health professionals on how much PA would be optimal for adults with NCDs. Additionally, the recommendations provide professionals entrusted in PA promotion the best strategies and interventions to raise low PA levels in adults with NCDs. The formulation of specific PA recommendations for adults with NCDs and their combination with recommendations on PA promotion is a unique characteristic of the German recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The high prevalence of physical inactivity is a global problem [1, 2] that contributes to increasing morbidity, higher rates of premature death [3], and increased economic costs [4]. In this context, the development of strategies to promote physical activity (PA) is an important challenge, both globally and nationally. A method of combatting high levels of inactivity is the development of PA guidelines. PA guidelines define the amount of health-enhancing activity through which significant health gains can be achieved (e.g. [5]). Both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Union have urged their member states to develop their own recommendations on a national level [5,6,7,8]. Even though many nations have developed these recommendations in recent years, including Canada, Great Britain, Australia, Switzerland, and Australia (e.g. [9, 10]), the resulting guidelines predominantly focus on healthy age-stratified target groups of children and adolescent, adults, and older adults. Thus far, the target group of individuals with noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) has received scant consideration.

NCDs, also known as chronic conditions or chronic diseases, are long lasting diseases. The main types of NCDs include cardiovascular diseases, cancers, musculosceletal diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, mental illness and diabetes [11]. The fact that there are hardly any national PA recommendations for adults with NCDs is surprising and problematic for several reasons. The ever-growing prevalence of NCDs [12] has become a global health issue. For most countries, adults with NCDs comprise one of the largest population groups. In Germany, for example, four out of every 10 adults report themselves as having at least one NCD [13]. PA has been proven to not only aid in the prevention [14] but also in the treatment of NCDs [15]. For more than 25 NCDs – such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, ischaemic heart disease, and clinical depression – PA is viewed as a medicine [16]; a medicine that positively influences symptoms and comorbidities, physical fitness and health-related quality of life [16]. Therefore, WHO [17] states that regular PA is the ‘best buy’ in controlling NCDs. Accordingly, WHO [5] specifies that their PA recommendations that are relevant for all healthy adults ‘also apply to adults with chronic noncommunicable conditions not related to mobility such as hypertension or diabetes.’ The PA recommendations of WHO are based on a vast body of evidence, and they have an immensely positive influence on global actions regarding PA promotion. However, a limitation of WHO’s recommendations is that their underlying scientific evidence is mainly based on the general population, meaning that specific scientific evidence regarding the health effects of PA on adults with NCDs has not been systematically considered. This is problematic because the health effects of PA are not identical in healthy adults and adults with a NCD. An important difference is that PA in adults with NCD often has a direct influence on pathophysiology and symptoms of the disease, e.g. improvements of blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetes or improvements of pain in chronic low back pain [16]. The extent to which the recommended PA dosages (volume, frequency, intensity and form of PA) for healthy adults optimally addresses these disease-specific health effects is unclear. Sometimes, less than the recommended 150 weekly minutes of moderate-intense PA for healthy adults is effective. For example, in adults with type 2 diabetes even brief bouts of walking at low intensities leads to reduced hyperglycaemia and lower resting blood pressure [18]. Mortality rates of adults with NCDs can also be positively influenced with significantly less than the recommended 150 min per week [19]. In order to maximise health benefits in adults with NCDs PA recommendations should be based on disease-specific evidence rather than evidence derived from the whole population. The lack of disease-specific evidence in PA recommendations not only applies to the WHO recommendations but also applies to nations that base their PA recommendations for adults with NCDs on WHO recommendations (e.g. Austria, Ireland, and Sweden). Other countries in Europe (e.g. Netherlands) excluded studies in people with NCDs in developing their national PA recommendations but state that the recommendations are useful for numerous specific groups of people with a chronic condition [20]. And some countries (e.g. Belgium, Greece, Spain, and Great Britain) do not make specific exercise recommendations for adults with NCDs [11]. This means that for many countries, there exists no evidence-based health-promoting PA recommendations for the large group of adults with NCDs. Thus, neither the adults affected by NCDs nor the health professionals involved in PA promotion know how much PA would be optimal.

Even more uncommon than missing PA recommendations, however, is to identify guidelines that not only define the health-enhancing dose of PA, but also recommend how PA promotion works for the specific target groups of adults with NCDs [21]. The majority of countries fail to provide such recommendations on PA promotion for adults with NCDs within a specific national scenario. Therefore, health professionals entrusted in PA promotion often lack recommendations for the best strategies and interventions to raise low PA levels in adults with NCDs.

With such limitations in mind, Germany developed its own national recommendations in 2016 [22]. The Committee for the Development of the German Recommendations on Physical Activity and Physical Activity Promotion consisted of an interdisciplinary working group made up of 16 scientists from six German universities. From an international perspective, the German recommendations are characterised by two unique features – namely, the formulation of specific recommendations for adults with NCDs and the systematic integration of guidelines for PA and PA promotion for adults with NCDs as well as for the other target groups (children and adolescents, adults, and older adults).

Following on from this, the purpose of this paper is to describe the methodology we used to develop the German national recommendations for physical activity and physical activity promotion in adults with NCDs and summarise the main results of this development. By doing this, the paper hopes to help other nations develop their own PA guidelines for the increasingly relevant target group of adults with NCDs. The paper also hopes to promote debate in relation to the implications of addressing specific target groups and the impact of this specific targeting on PA levels and public health policies.

Methods

Physical activity recommendations

For the development of the German PA recommendations for all target groups (children and adolescents, adults, older adults, and adults with NCDs), the same three-phase process was used (see Table 1).

For adults with NCDs, the three-phase process was initially applied to PA recommendations that were specific to the seven NCDs. Considering years of life lost due to premature death as well as years lived with disability, six of these NCDs are among the most burdensome diseases in both western Europe [12, 23] as a whole, especially in Germany [24]. The six NCDs are clinically stable ischemic heart disease, chronic non-specific back pain, clinical depression, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and stroke (> 6 months after the acute event). Additionally, osteoarthritis was added as seventh disease. Along with chronic non-specific back pain, osteoarthrosis accounts for the majority of diseases in the disease group of musculoskeletal diseases which is among the three most relevant disease groups regarding burden of disease [24]. In Germany, the lifetime prevalence of osteoarthritis is 27.1% for women and 17.9% for men [13]. Osteoarthritis is characterised by high levels of stress among those affected. Its negative effects include pain, functional restrictions in everyday life, and loss of quality of life [25]. Finally, generic PA recommendations for adults with NCDs were synthesised from an aggregation of the seven disease-specific PA recommendations. We previously published a comprehensive description of the entire methodology [26, 27]. The central aspects of the methodological approach are described below.

Phase 1: systematic literature review and establishment of quality criteria

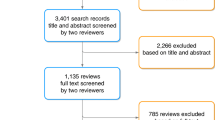

Separate literature searches were carried out for the seven NCDs (1A). The searches were comprised of PA recommendations, reviews of PA recommendations, and meta-analyses of the effects of PA, all published between 2010 and 2015 on the Medline database, either in German or English. Primary studies were not included.

As a first step in the selection of papers, titles and abstracts were checked for relevance. At this point, primary studies, non-human articles, papers not available in German or English, and papers that dealt with a different topic were excluded. Those papers deemed relevant were then analysed in their entirety. The full texts were subjected to a detailed relevance test that was conducted based on a standardised assessment sheet.

After checking the papers for the correct target population (adults with one of the seven relevant NCDs), all papers containing original PA recommendations for those adults were included. If a paper did not contain any original PA recommendations but contained a meta-analysis of the effects of PA for the relevant target group or a review of clinical guidelines or PA recommendations, then it was included.

For the standardised quality evaluation of the researched PA recommendations, an evaluation instrument was developed (1B). The evaluation instrument was used to ensure that methodically high-quality PA recommendations were selected. First, a list of 23 potential quality criteria was compiled based on the methodology of the German Instrument for Methodological Guideline Appraisal [28] and the refined instrument for Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care (AGREE II) methodology [29]. Second, the list of quality criteria was submitted to national experts for validation, based on the methodological approach of the Delphi surveys [30]. The experts were asked to check the proposed quality criteria for completeness and comprehensibility and to add any missing criteria (Delphi procedure stage 1). Finally, the revised list of quality criteria was submitted to the experts once again to evaluate its relevance with regard to the identification of high-quality PA recommendations (Delphi procedure stage 2).

Phase 2: evaluation, selection, and content analysis of identified physical activity recommendations

The yielded PA recommendations were evaluated based on their content and methodological quality using the evaluation instrument developed in phase 1 (2A). The domains that were evaluated were the scope and purpose of the recommendations, the methodological accuracy in their development, their clarity and differentiation of content, and their structure (see Additional file 1).

The quality evaluation formed the basis for the selection of what is here referred to as the source recommendations (2B). The source recommendations are those used as the basis for the German PA recommendations. The cut-off value for the selection of high-quality recommendations was > 60% in the domains of scope and purpose and methodological accuracy in the development of the recommendations. Additionally, reviews of recommendations and meta-analyses for the target group of adults with NCDs were included as supplementary resources. We did this without explicit quality ratings because even reviews with low quality could include statement on high quality PA recommendations and meta-analysis normally include a quality rating leading to the inclusion of studies with a high methodological quality. The identified source recommendations were then subjected to a detailed content analysis using a standardised analysis sheet that contained all 28 quality criteria (2C).

Phase 3: synthesis of content analysis and derivation of the recommendations for health-effective physical activity

Based on the detailed content analysis of the source recommendations and supplementary texts, seven disease-specific recommendations for health-relevant PA were compiled. These recommendations were then critically reviewed in relation to the reported health effects, dose-response relationships, and risk–benefit considerations of PA. Finally, the identification of cross-disease commonalities across the seven diseases (e.g., similar amounts of PA or similar types of PA recommended) was discussed resulting in the derivation of generic PA recommendations for adults with NCD.

Physical activity promotion recommendations

A systematic review of reviews regarding the efficacy/effectiveness of interventions for PA promotion in adults with NCDs was conducted. This review comprises one of the main pillars that led to the development of the German PA promotion recommendations for adults with NCDs.Footnote 1 The methodology used for the systematic review of reviews is briefly described below. A more detailed characterisation has already been explicated [33, 34].

Systematic review of review papers that examined the efficacy/effectiveness of interventions for physical activity promotion

A systematic review of review papers that examined the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions to enhance PA levels was conducted. Six electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, ERIC, and IBSS) were systematically searched for the terms ‘physical activity,’ ‘intervention,’ ‘evidence,’ ‘effect,’ ‘health,’ and ‘review.’ Alternative terms were also utilised for PA, including ‘bike,’ ‘biking,’ ‘cycling,’ ‘walking,’ ‘active transport,’ ‘human-powered transport,’ ‘sedentary,’ ‘exercise,’ and ‘sport.’ Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts for relevance based on the following criteria: a) the paper contains empirical results from single studies; b) the paper includes interventions focused on PA promotion or the reduction of physical inactivity; c) the paper focuses on the efficacy of interventions; and d) the paper is written in English or German. For the identified relevant papers, a secondary screening process of the entire text was conducted by two independent reviewers based on the same criteria. Finally, additional papers were identified via screening the reference lists of identified articles.

An independent researcher assessed the quality of the identified papers using two separate tools – namely, the AGREE II instrument [29], which was used in the formulation of the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines [35], and our own quality criteria, which allowed for higher levels of differentiation regarding the methodological quality criteria of each review (see Additional file 2). Based on both instruments, percentage values were calculated for each paper. Such values indicated the percentages of fulfilled criteria for each paper, both on the basis of the AGREE II tool and our newly developed instrument. These percentage values were calculated based on the number of applicable criteria (e.g. some criteria were only applicable for meta-analyses). The combined results defined the quality of each paper as high, medium, or low. A paper was classified as being of high quality when at least 75% of the AGREE II criteria and 60% of our own criteria were fulfilled. Papers were defined as being of medium quality if they satisfied just one of these thresholds, while low-quality papers reached neither threshold.

Expert consensus

A group of scientific experts developed the German Recommendations for Physical Activity Promotion in a process of consensus. Two individuals with expertise in PA promotion were assigned the task of assessing the efficacy/effectiveness of the identified papers. Following the methodology proposed by Smith et al. [36], both reviewers applied a standardised process of analysis that consisted of six steps. First, an independent review of the identified literature was conducted, and a draft summary statement was compiled. Second, a meeting of both reviewers was held to discuss statements and agree on a conjointly revised summary statement. Third, the summary statement was presented and discussed with the reviewers who were assigned to other target groups (e.g. older adults). Fourth, a workshop meeting was held to present each summary statement to the entire project group (including scientists involved in drafting the PA promotion recommendations as well as an International Scientific Advisory Board). Each summary statement was revised on the basis of expert feedback. Fifth, the recommendations for each target group were drafted using the finalised summary statements. A template specifying how to draft the recommendations was developed and provided by the project leaders. Sixth, the drafted recommendations were circulated for review by the entire project group as well as the International Scientific Advisory Board. Recommendations were made when both reviewers rated the available evidence as being of strong or medium quality, based on the following criteria: (1) the number of available reviews focusing on a given intervention type is sufficient to formulate recommendations; and (2) the reviews show conclusive evidence for efficacy. Recommendations were not made when the above criteria were not fulfilled (i.e. when the available evidence was weak or inconclusive).

Results

Physical activity recommendations

Existing physical activity recommendations for adults with NCDs

The PA recommendations for adults with NCDs were derived from a detailed content analysis of 59 source recommendations and texts: arthrosis (hip and knee) [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]; type 2 diabetes mellitus [52,53,54,55]; COPD [56,57,58,59,60,61]; clinically stable ischemic heart disease [62,63,64,65]; stroke [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77]; clinical depression [78,79,80,81,82,83,84]; and chronic non-specific back pain [85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. The detailed references of all 48 articles and their quality ratings can be found in Additional file 3.

The content analysis of the 48 articles shows that PA and/or exercise is recommended for all seven analysed NCDs as an effective treatment option. Furthermore, the content analysis makes it clear that the positive benefits of PA outweigh its costs and side effects; a physically inactive lifestyle is associated with significantly greater health risks than a lifestyle with high levels of PA. Details regarding the health effects, risks, and side effects of PA within the individual disease-specific PA recommendations are reported by Rütten et al. [22].

Main recommendations for physical activity

The following recommendations are for adults aged between 18 and 65 with an NCD such as type 2 diabetes, COPD, arthritis in the hip or knee, clinically stable ischemic heart disease, stroke (> 6 months after the acute event), clinical depression, or chronic non-specific back pain.

In order to achieve significant health effects (e.g., improved symptoms, enhanced physical functioning, improved psychological health and quality of life), adults with NCDs should be physically active on a regular basis. However, health-enhancing results can also occur when individuals who were entirely physically inactive become somewhat more active. Every step away from physical inactivity is important, as each step leads to increased health benefits.

The PA recommendations for adults with NCDs are presented in Table 2. They do not differ from the PA recommendations for healthy adults and represent the minimum levels of PA one should meet in order to maintain and promote one’s health comprehensiveley.

Additional recommendations for safe (re-)entry into a physically active lifestyle

PA is associated with a variety of positive health effects for adults with NCDs. However, PA is not completely without risk for such individuals. The beginning of a physical training programme or phases during which PA levels are increased can be associated with a higher risk of side effects and adverse events. Therefore, based on the content analysis of the source recommendations [38, 39, 42, 47, 52, 55, 60,61,62,63, 65,66,67,68,69, 72, 83,84,85, 87, 94, 96,97,98,99,100] the developed recommendations also include information on safety enhancement. To increase the safety and effectiveness of PA, adults with NCDs should:

- (1)

have a (sports) medical examination carried out when commencing a physically active lifestyle or entering a PA programme;

- (2)

decide, along with a doctor, whether practicing PA independently is safe and appropriate, or whether it is advisable to be under the professional care of PA professionals at the outset;

- (3)

tailor the PA dose (type of PA, exercise intensity, duration, frequency) to individual needs and functional levels with the assistance of a PA professional; and

- (4)

obtain professional advice from healthcare professionals during the phases of the progression of the illness, when experiencing lack of control over the illness, or when one’s health status is deteriorating, as it may be necessary to adjust or change PA or momentarily interrupt PA.

Physical activity promotion recommendations

The PA promotion recommendations for adults with NCDs were developed based on 18 systematic reviews. Most of the reviews investigated which interventions resulted in increased PA levels. The detailed quality ratings of the papers are included in Additional file 4. All of the papers conducted their reviews in healthcare settings. Two analysed general PA promotion interventions [101, 102], seven focused on indication-based PA promotion [103,104,105,106,107,108,109], three assessed interventions in primary care [110,111,112], and six dealt with the effects of different PA-promoting interventions [113,114,115,116,117,118].

Health behaviour change theories

One finding pertains to the utilisation of theory-based approaches of health behaviour to ensure PA behaviour change. Leidy et al. [102] have shown that using one of three theories of behavioural change (transtheoretical model, social cognitive theory, health belief model) leads to improved results with regard to PA promotion. Mastellos et al.’s [114] Cochrane review demonstrates the effectiveness of PA-promoting interventions when based on the transtheoretical model. Short et al.’s [103] review concludes that employing techniques of behavioural change (e.g. self-monitoring and goal setting) derived from a variety of theories can be effective in PA promotion. The review by McGrane et al. [119] also suggests that effective changes in movement behaviour can be achieved when based on various theories (e.g. self-determination theory, social cognitive theory, cognitive behavioural theory, theory of motivational interviewing). However, the authors argue that it remains difficult to determine which theory-based approach works best.

Techniques of health behaviour change and interventional content, settings, and delivery mode

Several reviews provided medium-level evidence on the effectiveness of certain behaviour change techniques. Short et al. [103] showed that the behaviour change techniques of self-monitoring, goal setting, positive reinforcement, and the elicitation of social support can be useful for adults with breast cancer. Interventions for adults with rheumatoid arthritis were investigated in two reviews [104, 105]. Cramp et al. [104] conclude that there are several promising behaviour change techniques (e.g. goal setting and performance feedback). Iversen et al. [105] argue that coaching and counselling appear to have a positive impact on PA participation. The research findings identified just one study that evidenced the positive effects of a PA-promoting intervention for individuals with cystic fibrosis [106], with limited evidence showing that activity counselling and advice for engaging in a home-based exercise programme may increase PA levels. Conn et al. [101] state that self-monitoring PA behaviour improves PA levels but found that other behaviour change techniques (e.g. supervised exercise sessions, exercise prescription, fitness testing, goal setting, contracting, problem solving, barrier management, and stimuli/cues) were unrelated to PA outcomes. One review analysed home-based exercise programmes prescribed by health care practitioner for adults with chronic low back pain, and most of the studies reviewed showed significant effects on PA levels [107]. For adults who had had a stroke, specific behavioural interventions, such as targeted counselling or specially tailored exercise programmes, are more effective than exercise programmes and general counselling [108]. Three other reviews [102, 108, 110] confirm the usefulness of adaptating and tailoring PA promotion interventions to the individual needs of the target group. The typical rehabilitation measures comprising PA therapy combined with psychosocial or educational interventions can increase PA behaviour in the short term for individuals with cardiovascular disease [109]. Two reviews concluded that the counselling method of motivational interviewing is effective for individuals with NCDs [116, 119]. Based on the review conducted by Manis et al. [113], there is strong evidence for the effectiveness of pedometer-based interventions for adults with musculoskeletal diseases.

Concerning interventions in primary and/or curative care, one review shows that exercise referral schemes can lead to small positive effects in the short and medium term [110]. Orrow et al. [112] conducted a review and meta-analysis based on a broad range of interventions and showed that interventions in primary care can be effective.

Four reviews focused on the effectiveness of delivery modes of interventions [114, 115, 117, 118]. Based on these reviews there is inconclusive evidence for the effectiveness of internet-based interventions in cardiac rehabilitation [114, 115], and conflicting evidence for the effectiveness of web-based interventions for patients with NCDs [118]. Furthermore, the reviews showed evidence of the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions delivered by nurses in primary healthcare [117].

Targeting physical activity behaviour

One review analysing general interventions for PA promotion in adults with NCDs found that the effects of interventions are stronger when PA behaviour is targeted specifically rather than in combination with other health behaviours [101].

Recommendations for physical activity promotion

All papers in the systematic review refer to health care settings, e.g. general practitioners practices or clinics. Accordingly, recommendations for PA promotion in adults with NCDs were made for interventions in healthcare institutions (see Table 3).

Discussion

The German guidelines for PA and PA promotion for adults with NCDs provide recommendations for the amount of PA necessary to yield substantial health benefits and strategies for PA promotion so that the recommended level of PA is successfully reached. Thus far, and to the best of our knowledge, such a combination of recommendations is the first of its kind. The concomitant implementation of both PA and PA promotion recommendations produces considerable health gains in what is, to date, one of the largest and most inactive adult subgroups.

The German recommendations for PA and PA promotion represent a fundamental building block in terms of mobilising national efforts to fight against physical inactivity. On the one hand, professional organisations in the fields of medicine, exercise therapy, and/or rehabilitation can use these guidelines to promote increased PA levels among individuals with NCDs. On the other hand, health professions and societies ought to support the dissemination and implementation of these guidelines in order to maximise their influence and ensure that the target population is reached.

The ideal dosage of PA for various target groups has been long discussed. Evidence supporting the claim that PA promotes health among people with NCDs is plentiful [16]. When considering a wide scope of health outcomes, many adults with NCDs respond to higher levels of PA by producing better health effects, and the understanding that ‘a lot helps a lot’ still rings true. Nonetheless, there are other outcomes in this regard. For example, a higher level of PA intensity might have negative effects on psychological well-being [120]. For some outcomes, much of the maximal effect is achieved from a relatively low dose of PA; for example, the greatest reduction in mortality rates occurs at PA levels already well below the recommended minimum dose of 150 min/week [121]. The German PA recommendations for adults with NCDs are based on a synthesis of the available recommendations. Consequently, they also use the concept of the minimum dose for substantial health gains. Nevertheless, it is a task for future researchers to question the concept of minimum doses and determine the dose–response relationships for certain health outcomes (e.g., mortality, morbidity, physical functioning, psychological health and well-being).

The current German PA recommendations for individuals with NCDs are identical to those suggested for healthy adults (i.e. 150 min of moderate PA plus two strength-training sessions per week). This generic outcome was synthesised based on seven carefully prepared, high-quality, indication-specific recommendations. Prior to our work, it was unclear how appropriate it was to transfer PA recommendations for healthy adults to adults with NCDs. Based on our extensive work, the theory that the recommended dose of PA for healthy adults leads to substantial health gains in most individuals with NCDs is now evidence-based. Notwithstanding, this dose might be physically and psychologically excessive for some individuals with NCDs – this cannot be ignored. The importance of patient-centred tailoring plans and programmes that focus on adjusting the dosage to individual needs and functionality levels is therefore emphasised. This supports and values adults with NCDs being regularly active, according to their current health status and their ability.

In addition to PA behaviour, other health-related behaviours, including smoking, alcohol, diet, and medication, have a major influence on the health of individuals with NCDs [11]. It is understood and anticipated that the recommendation to change only one behaviour at a time might not be practical to implement in a real-world setting. For example, in a typical rehabilitation context, it is often recommended to try and adjust multiple behaviours at once. Even if this is medically recommended and meaningful, the probability of successful behaviour change decreases as a result. Influencing multiple behaviour patterns individually might be a better approach. Addressing the promotion of PA first might be the best option, as regular PA can act as a catalyst to promote changes in other health behaviours [122].

The summarised evidence indicates that an intervention based on different behaviour-change theory-based approaches might result in increased PA levels compared to interventions that do not utilise such approaches. Accordingly, the PA promotion recommendations broadly state that interventions should be based on a theoretical model of behaviour change. Theoretical models help to understand physical inactivity and develop appropriate and targeted PA promotion interventions [123]. Thereby, theory-based interventions increase the probability of successful PA promotion. However, Davis et al. [124] identified 82 different behaviour-change theories, and the question remains as to which of these behavioural theories should be used. The evidence on which the German PA promotion recommendations are based refers to several theories and most of the included reviews, except for that of McGrane et al. [119], who take into account only theories that could be assigned to the social cognitive theoretical framework [125]. Nevertheless, three other key theoretical frameworks (i.e. humanistic, dual process, and socioecological) are available [125]. However, our methodological approach of reviewing reviews did not allow us to identify any evidence regarding the effectiveness of these three frameworks. As such, we were unable to make a decision in relation to which theoretical approach works best. On the basis of the literature included, it was not possible to make robust, unambiguous statements about the effectiveness of individual behavioural change techniques. The future development of recommendations for PA promotion should include original research to identify the most promising theories and to determine which of the 93 techniques for PA promotion are most effective [126], especially in adults with NCDs.

The basic premise of the Committee for the German Recommendations for Physical Activity and Physical Activity Promotion was to develop recommendations for specific target groups. Independent and separate working processes were implemented for children and adolescents, adults, older adults, and adults with NCDs. Thus, the German recommendations include more diverse population subgroups and fulfil a requirement of the Advisory Committee of the United States [127]. Due to the rather low level of evidence of PA promotion in individuals with NCDs, the recommendations for adults with NCDs are less detailed compared to the other target groups [33]. Nevertheless, additional to the development of the target-specific recommendations for PA promotion, general quality criteria for the conceptualization, implementation, and evaluation of interventions for PA promotion were developed [31]. For example, during the conceptualisation phase, quality criteria, such as the multidimensionality of the intervention, the involvement of different stakeholders, and the specification of goals and target behaviour, need to be considered. Other criteria relate to, for example, communication, sustainability, and resources during implementation as well as to different aspects of the evaluation (see Additional file 5 for a list of all quality criteria). Even though there is no specific evidence in relation to adults with NCDs for most of these criteria, the criteria support the conceptualisation, implementation, and evaluation of interventions for adults with NCDs.

It is important to highlight that nations should not only develop PA and PA promotion recommendations. In order to maximise the reach of the recommendations, it is crucial to attempt to disseminate said recommendations to the appropriate individuals, communities, and organisations at the right time. In order to facilitate understanding of the developmental process for PA recommendations, it has been proposed that the German context should be analysed through the lens of the multiple streams approach (MSA) [21]. In summary, the MSA was developed in 1984 to study policy processes and to clarify why certain issues receive or attract attention and others do not (agenda setting). It posits that the political process comprises three streams that flow independently – namely, the problem stream (i.e. specific issues perceived as problematic and in need of solution), the policy stream (i.e. the development of strategies and possible policies to address the stated problem), and the politics stream (i.e. operating actors such as political parties, institutions, and interest groups). The interaction between the three streams might facilitate or hinder the effective dissemination and adoption of national PA and PA promotion guidelines. As for the German context, including PA promotion as a stand-alone topic in the political agenda might have come as a result of said interaction. This propelled several different strategies and actions that boosted the impact of PA and PA promotion recommendations nationwide. A more detailed description and dissection of the aforementioned strategies and actions was published by Rütten et al. [21].

Limitations

The methodological approach used to develop both guidelines is not without its restrictions. A goal of the Committee for the Development of German Guidelines for Physical Activity was to address the target group of adults with NCDs. However, only a (very) limited amount of finances, time, and human resources was made available for the overall development of the guidelines.

Due to said limitations, the committee opted to apply an overall methodological approach based on the extraction and synthesis of the latest high-quality reviews, meta-analyses, and existing recommendations. Original scientific works, for instance, could unfortunately not be taken into account during this development. The consideration of these works would have allowed for additional and relevant topics to be explored in more detail. As an example of this consequence, the current PA guidelines do not incorporate the role of sedentary behaviour and its impact on adults with NCDs. In addition, the included literature on PA promotion was only assessed independently by one person instead of two. Furthermore, our literature search was limited to PA recommendations published after the year 2009 and did not include searches for grey literature. In addition to the time and financial restrictions mentioned above, specific PA recommendations for adults with NCDs is a relatively new field of research. The chosen procedure therefore identifies the most recently published PA recommendations, but it is possible that we have overlooked grey literature (e.g. guideline-building reports) and high-quality older recommendations due to this temporal limitation.

As for the PA promotion guidelines, general recommendations can be provided for interventions in terms of their theoretical foundations. However, investigating the most effective theory-based intervention or conducting comparative analyses of the effects of different theories was beyond the scope of our methodological approach.

The underlying evidence comes exclusively from interventions carried out in the healthcare system. Studies carried out in other settings (e.g., educational system, work place) are lacking. It is likely that the consideration of original scientific papers would have identified further studies conducted in other settings. It is likely that this would have led to more multi-faceted recommendations for the promotion of PA in adults with NCDs.

The robustness of the selected methodology as well as its economic limitations represent a compromise that aims to include individuals with different NCDs, as they represent a crucial target group from a public health perspective. When compared to Canada, for example, Germany used a low-cost approach, which resulted in numerous methodological limitations. Such an approach, however, seems to be feasible for other nations, as it helps to curtail restraints imposed by a scarcity of available resources.

Conclusion

The development of PA recommendations for adults with NCDs provides an evidence-based target dose of PA that adults with different NCDs can use to achieve significant health outcomes; the development of PA promotion recommendations for adults with NCDs helps to achieve that dose. Thus, the development of evidence-based PA and PA promotion guidelines is an important building block in relation to the initiation and implementation of actions for PA-related health promotion in Germany. The formulation of specific PA recommendations for adults with NCDs and their combination with specific PA promotion recommendations renders the German recommendations quite unique. The German Recommendations for PA and PA promotion for adults with NCDs help other nations develop their own PA guidelines for the increasingly relevant target group of adults with NCDs.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Notes

Additionally, two reviews were carried out to analyse the cost-effectiveness of PA promotion interventions and develop generic quality criteria for the conception, implementation, and evaluation of interventions for the promotion of PA. The results of these reviews have been published [31, 32] and are beyond the scope of this article.

Abbreviations

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- MSA:

-

Multiple streams approach

- NCD:

-

Noncommunicable disease

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Kohl HW, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, Kahlmeier S. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet. 2012;380:294–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016. A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7.

Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380:219–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9.

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, van Mechelen W, Pratt M. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2016;388:1311–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X.

World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

WHO. Global strategy on diet, physical activity, and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

European Union Council. Council recommendation on promoting health-enhancing physical activity across sectors. 2013. http://ec.europa.eu/sport/library/documents/hepa_en.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2018.

European Union. EU physical activity guideliens: Reommended poliy actions in support of health-enhancing phyiscal activity. 2008. http://ec.europa.eu/sport/library/policy_documents/eu-physical-activityguidelines-2008_en.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2018.

Kahlmeier S, Wijnhoven TMA, Alpiger P, Schweizer C, Breda J, Martin BW. National physical activity recommendations: systematic overview and analysis of the situation in European countries. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1412-3.

Stamatakis E, Ding D, Hamer M, Bauman AE, Lee I-M, Ekelund U. Any public health guidelines should always be developed from a consistent, clear evidence base. Br J Sports Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100394.

WHO. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4.

Lange C. Daten und Fakten. Ergebnisse der Studie "Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell 2012" [Facts and figures. Results of the study "Health in Germany 2012"]. Berlin: Robert-Koch-Institut; 2014. German.

Booth FW, Roberts CK, Laye MJ. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:1143–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c110025.

World Health Organization. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healtier world. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine - evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(Suppl 3):1–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12581.

WHO. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: 2013-2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Dempsey PC, Blankenship JM, Larsen RN, Sacre JW, Sethi P, Straznicky NE, et al. Interrupting prolonged sitting in type 2 diabetes: nocturnal persistence of improved glycaemic control. Diabetologia. 2017;60:499–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-4169-z.

Warburton DER, Charlesworth S, Ivey A, Nettlefold L, Bredin SSD. A systematic review of the evidence for Canada's physical activity guidelines for adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010:7–39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-39.

Weggemans RM, Backx FJG, Borghouts L, Chinapaw M, Hopman MTE, Koster A, et al. The 2017 Dutch physical activity guidelines. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0661-9.

Rütten A, Abu-Omar K, Messing S, Weege M, Pfeifer K, Geidl W, Hartung V. How can the impact of national recommendations for physical activity be increased? Experiences from Germany. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0396-8.

Rütten A, Pfeifer K, editors. National recommendations for physical activity and physical activity promotion. Erlangen: FAU University Press; 2016.

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0.

Plass D, Vos T, Hornberg C, Scheidt-Nave C, Zeeb H, Krämer A. Trends in disease burden in Germany: results, implications and limitations of the global burden of disease study. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:629–38. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2014.0629.

Rabenberg M, editor. Arthrose [Osteoarthrosis]. Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut; 2013. German.

Geidl W, Pfeifer K. Hintergrund und methodisches Vorgehen bei der Entwicklung von nationalen Empfehlungen für Bewegung [Background and methodology of the development of German physcial activity guidelines]. Gesundheitswesen. 2017;79:S4–S10. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-123703. German.

Pfeifer K, Geidl W. Bewegungsempfehlungen für Erwachsene mit einer chronischen Erkrankung – Methodisches Vorgehen, Datenbasis und Begründung [Physical activity recommendations for adults with a chronic disease: methods, database and rationale]. Gesundheitswesen. 2017;79:S29–35. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-123699. German.

Kopp IB. Perspectives in guideline development and implementation in Germany. Z Rheumatol. 2010;69:298–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-009-0526-3.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–42. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090449.

Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inform Managment. 2004;42:15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002.

Messing S, Rütten A. Qualitätskriterien für die Konzipierung, Implementierung und Evaluation von Interventionen zur Bewegungsförderung. Ergebnisse eines state-of-the-art reviews [Quality criteria for the conception, implementation and Evaluation of interventions for physical activity promotion: a state-of-the-art review]. Gesundheitswesen. 2017;79:S60–5. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-123378. German.

Abu-Omar K, Rütten A, Burlacu I, Schätzlein V, Messing S, Suhrcke M. The cost-effectiveness of physical activity interventions: a systematic review of reviews. Prev Med Rep. 2017;8:72–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.08.006.

Abu-Omar K, Rütten A, Messing S, Pfeifer K, Ungerer-Röhrich U, Goodwin L, et al. The German recommendations for physical activity promotion. J Public Health. 2018;71:1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-018-0986-5.

Abu-Omar K, Rütten A, Burlacu I, Messing S, Pfeifer K, Ungerer-Röhrich U. Systematischer review von Übersichtsarbeiten zu Interventionen der Bewegungsförderung. Methodologie und erste Ergebnisse [A systematic review of reviews of interventions for the promotion of physical activity: methodology and first results]. Gesundheitswesen. 2017;79:S45–50. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-123502. German.

Tremblay MS, Warburton DER, Janssen I, Paterson DH, Latimer AE, Rhodes RE, et al. New Canadian physical activity guidelines. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:36–46; 47-58. https://doi.org/10.1139/H11-009.

Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-15.

Beckwee D, Vaes P, Cnudde M, Swinnen E, Bautmans I. Osteoarthritis of the knee: why does exercise work? A qualitative study of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:226–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2012.09.005.

Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JWJ, Andreassen O, Christensen P, Conaghan PG, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1125–35. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745.

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:465–74.

Larmer PJ, Reay ND, Aubert ER, Kersten P. Systematic review of guidelines for the physical management of osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:375–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.011.

Lu M, Su Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Wang W, He Z, et al. Effectiveness of aquatic exercise for treatment of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Z Rheumatol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-014-1559-9.

McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22:363–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003.

Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: the chronic osteoarthritis management initiative of the U.S. bone and joint initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.012.

Stoffer MA, Smolen JS, Woolf A, Ambrozic A, Berghea F, Boonen A, et al. Development of patient-centred standards of care for osteoarthritis in Europe: the eumusc.net-project. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206176.

Uthman OA, van der Windt DA, Jordan JL, Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Peat GM, Foster NE. Exercise for lower limb osteoarthritis: systematic review incorporating trial sequential analysis and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5555. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f5555.

Escalante Y, Garcia-Hermoso A, Saavedra JM. Effects of exercise on functional aerobic capacity in lower limb osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14:190–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2010.10.004.

Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD004376. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004376.pub3.

Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD007912. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007912.pub2.

Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Hootman JM. Effects of exercise on depression in adults with arthritis: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0533-5.

Zacharias A, Green RA, Semciw AI, Kingsley MIC, Pizzari T. Efficacy of rehabilitation programs for improving muscle strength in people with hip or knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22:1752–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.07.005.

Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden NK, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18:476–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013.

Geidl W, Pfeifer K. Körperliche Aktivität und körperliches Training in der Rehabilitation des Typ-2-Diabetes (Physical activity and exercise for the Rehabilitation of type 2 diabetes). Rehabilitation. 2011;50:255–65. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1280805. German.

O’Hagan C, de Vito G, Boreham CA. Exercise prescription in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sports Med. 2013;43:39–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-012-0004-y.

Rydén L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, Berne C, Cosentino F, Danchin N, et al. ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD - summary. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2014;11:133–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479164114525548.

Sigal RJ, Armstrong MJ, Colby P, Kenny GP, Plotnikoff RC, Reichert SM, Riddell MC. Physical activity and diabetes. Canad J Diabet. 2013;37:S40–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.018.

Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Maturu VN, Dhooria S, Prasad KT, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: joint ICS/NCCP (I) recommendations. Lung India. 2013;30:228–67. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-2113.116248.

Iepsen UW, Jorgensen KJ, Ringbaek T, Hansen H, Skrubbeltrang C, Lange P. A systematic review of resistance training versus endurance training in COPD. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2015;35:163–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000105.

Marciniuk DD, Brooks D, Butcher S, Debigare R, Dechman G, Ford G, et al. Optimizing pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease--practical issues: a Canadian thoracic society clinical practice guideline. Can Respir J. 2010;17:159–68.

Pan L, Guo YZ, Yan JH, Zhang WX, Sun J, Li BW. Does upper extremity exercise improve dyspnea in patients with COPD? A meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2012;106:1517–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2012.08.002.

Ng BH, Tsang HW, Ng BF, So CT. Traditional Chinese exercises for pulmonary rehabilitation: evidence from a systematic review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2014;34:367–77. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000062.

Garvey C, Fullwood MD, Rigler J. Pulmonary rehabilitation exercise prescription in chronic obstructive lung disease: US survey and review of guidelines and clinical practices. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2013;33:314–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0b013e318297fea4.

Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, Berra K, Blankenship JC, Dallas AP, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:e44–e164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.013.

Misra A, Nigam P, Hills AP, Chadha DS, Sharma V, Deepak KK, et al. Consensus physical activity guidelines for Asian Indians. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14:83–98. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2011.0111.

Oldridge N. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease: meta-analysis outcomes revisited. Futur Cardiol. 2012;8:729–51. https://doi.org/10.2217/fca.12.34.

Serón P, Lanas F, Ríos E, Bonfill X, Alonso-Coello P. Evaluation of the quality of clinical guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation: a critical review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2015;35:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000075.

Billinger SA, Arena R, Bernhardt J, Eng JJ, Franklin BA, Johnson CM, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2532–53. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000022.

Bryer A, Connor M, Haug P, Cheyip B, Staub H, Tipping B, et al. South African guideline for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2010: a guideline from the south African stroke society (SASS) and the SASS writing committee. S Afr Med J. 2010;100:747–78.

Gallanagh S, Quinn TJ, Alexander J, Walters MR. Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of stroke. ISRN Neurol. 2011;2011:953818. https://doi.org/10.5402/2011/953818.

Pang MYC, Charlesworth SA, Lau RWK, Chung RCK. Using aerobic exercise to improve health outcomes and quality of life in stroke: evidence-based exercise prescription recommendations. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35:7–22. https://doi.org/10.1159/000346075.

Pollock A, Farmer SE, Brady MC, Langhorne P, Mead GE, Mehrholz J, van Wijck F. Interventions for improving upper limb function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD010820. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010820.pub2.

Steib S, Schupp W. Therapiestrategien in der Schlaganfallnachsorge. Inhalte und Effekte [Therapy strategies in stroke aftercare. Content and effects]. Nervenarzt. 2012;83:467–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-011-3396-2. German.

Zehr EP. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: stroke and spinal cord injury. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;31(Suppl 1):36. https://doi.org/10.1139/h11-055.

Adamson BC, Ensari I, Motl RW. Effect of exercise on depressive symptoms in adults with neurologic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2015.01.005.

Coupar F, Pollock A, Legg LA, Sackley C, van Vliet P. Home-based therapy programmes for upper limb functional recovery following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD006755. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006755.pub2.

Coupar F, Pollock A, van Wijck F, Morris J, Langhorne P. imultaneous bilateral training for improving arm function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD006432. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006432.pub2.

Lubetzky-Vilnai A, Kartin D. The effect of balance training on balance performance in individuals poststroke: a systematic review. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2010;34:127–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/NPT.0b013e3181ef764d.

Saltychev M, SjogrenT T, Barlund E, Laimi K, Paltamaa J. Do aerobic exercises really improve aerobic capacity of stroke survivors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;52:233–43.

Berk M, Sarris J, Coulson CE, Jacka FN. Lifestyle management of unipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2013:38–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12124.

Danielsson L, Noras AM, Waern M, Carlsson J. Exercise in the treatment of major depression: a systematic review grading the quality of evidence. Physiother Theory Pract. 2013;29:573–85. https://doi.org/10.3109/09593985.2013.774452.

Nyström MBT, Neely G, Hassmen P, Carlbring P. Treating major depression with physical activity: a systematic overview with recommendations. Cogn Behav Ther. 2015;44:341–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1015440.

Park S-C, Oh HS, Oh D-H, Jung SA, Na K-S, Lee H-Y, et al. Evidence-based, non-pharmacological treatment guideline for depression in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:12–22. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.1.12.

Perraton LG, Kumar S, Machotka Z. Exercise parameters in the treatment of clinical depression: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:597–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01188.x.

Ranjbar E, Memari AH, Hafizi S, Shayestehfar M, Mirfazeli FS, Eshghi MA. Depression and exercise: a clinical review and management guideline. Asian J Sports Med. 2015;6:e24055. https://doi.org/10.5812/asjsm.6(2)2015.24055.

Knapen J, Vancampfort D, Morien Y, Marchal Y. Exercise therapy improves both mental and physical health in patients with major depression. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:1490–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.972579.

Chilibeck PD, Vatanparast H, Cornish SM, Abeysekara S, Charlesworth S. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity: arthritis, osteoporosis, and low back pain. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36(Suppl 1):79. https://doi.org/10.1139/h11-037.

Haladay DE, Miller SJ, Challis J, Denegar CR. Quality of systematic reviews on specific spinal stabilization exercise for chronic low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43:242–50. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2013.4346.

Ribaud A, Tavares I, Viollet E, Julia M, Herisson C, Dupeyron A. Which physical activities and sports can be recommended to chronic low back pain patients after rehabilitation? Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2013;56:576–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2013.08.007.

Pillastrini P, Gardenghi I, Bonetti F, Capra F, Guccione A, Mugnai R, Violante FS. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for chronic low back pain management in primary care. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:176–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.03.019.

Steele J, Bruce-Low S, Smith D. A review of the clinical value of isolated lumbar extension resistance training for chronic low back pain. PM R. 2015;7:169–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.10.009.

Dagenais S, Tricco AC, Haldeman S. Synthesis of recommendations for the assessment and management of low back pain from recent clinical practice guidelines. Spine J. 2010;10:514–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2010.03.032.

Fersum KV, Dankaerts W, O'Sullivan PB, Maes J, Skouen JS, Bjordal JM, Kvale A. Integration of subclassification strategies in randomised controlled clinical trials evaluating manual therapy treatment and exercise therapy for non-specific chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:1054–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2009.063289.

Ladeira CE. Evidence based practice guidelines for management of low back pain: physical therapy implications. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2011;15:190–9.

Standaert CJ, Friedly J, Erwin MW, Lee MJ, Rechtine G, Henrikson NB, Norvell DC. Comparative effectiveness of exercise, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation for low back pain. Spine. 2011;36:30. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822ef878.

van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, Koes BW, van Tulder MW. Exercise therapy for chronic nonspecific low-back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.002.

Wang X-Q, Zheng J-J, Yu Z-W, Bi X, Lou S-J, Liu J, et al. A meta-analysis of core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52082. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052082.

Achttien RJ, Staal JB, van der Voort S, Kemps HMC, Koers H, Jongert MWA, Hendriks EJM. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease: a practice guideline. Neth Heart J. 2013;21:429–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12471-013-0467-y.

Riddell MC, Burr J. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: diabetes mellitus and related comorbidities. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:S154–89. https://doi.org/10.1139/h11-063.

Vanhees L, GeladaS N, Hansen D, Kouidi E, Niebauer J, Reiner Z, et al. Importance of characteristics and modalities of physical activity and exercise in the management of cardiovascular health in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors: recommendations from the EACPR (part II). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19:1005–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741826711430926.

Mendes R, Sousa N, Reis VM, Themudo-Barata JL. Prevention of exercise-related injuries and adverse events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Prim Care. 2013;89:715–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-132222.

Iepsen UW, Jorgensen KJ, Ringbaek T, Hansen H, Skrubbeltrang C, Lange P. A combination of resistance and endurance training increases leg muscle strength in COPD: an evidence-based recommendation based on systematic review with meta-analyses. Chron Respir Dis. 2015;12:132–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972315575318.

Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Brown SA, Brown LM. Meta-analysis of patient education interventions to increase physical activity among chronically ill adults. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:157–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.004.

Leidy NK, Kimel M, Ajagbe L, Kim K, Hamilton A, Becker K. Designing trials of behavioral interventions to increase physical activity in patients with COPD: insights from the chronic disease literature. Respir Med. 2014;108:472–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2013.11.011.

Short CE, James EL, Stacey F, Plotnikoff RC. A qualitative synthesis of trials promoting physical activity behaviour change among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:570–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0296-4.

Cramp F, Berry J, Gardiner M, Smith F, Stephens D. Health behaviour change interventions for the promotion of physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013;11:238–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1049.

Iversen MD, Brawerman M, Iversen CN. Recommendations and the state of the evidence for physical activity interventions for adults with rheumatoid arthritis: 2007 to present. Int J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;7:489–503. https://doi.org/10.2217/ijr.12.53.

Cox NS, Alison JA, Holland AE. Interventions for promoting physical activity in people with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):1–51.

Beinart NA, Goodchild CE, Weinman JA, Ayis S, Godfrey EL. Individual and intervention-related factors associated with adherence to home exercise in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2013;13:1940–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.027.

Morris JH, Macgillivray S, McFarlane S. Interventions to promote long-term participation in physical activity after stroke: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:956–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.12.016.

ter Hoeve N, Huisstede BMA, Stan HJ, van Domburg RT, Sunamura M, van den Berg-Emons RJG. Does cardiac rehabilitation after an acute cardiac syndrome lead to changes in physical activity habits? Systematic review. Phys THer. 2015;95:167–79.

Pavey TG, Anokye N, Taylor AH, Trueman P, Moxham T, Fox KR, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of exercise referral schemes: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:i–xii, 1–254. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta15440.

McGrane N, Galvin R, Cusack T, Stokes E. Addition of motivational interventions to exercise and traditional physiotherapy: a review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2014.04.009.

Orrow G, Kinmonth AL, Sanderson S, Sutton S. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion based in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344:16. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1389.

Mansi S, Milosavljevic S, Baxter GD, Tumilty S, Hendrick P. A systematic review of studies using pedometers as an intervention for musculoskeletal diseases. BMC Musculoskel Disord. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-231.

Mastellos N, Gunn LH, Felix LM, Car J, Majeed A. Transtheoretical model stages of change for dietary and physical exercise modification in weight loss management for overweight and obese adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2.

Munro J, Angus N, Leslie SJ. Patient focused internet-based approaches to cardiovascular rehabilitation - a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19:347–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X13501763.

O'Halloran PD, Blackstock F, Shields N, Holland A, Iles R, Kingsley M, et al. Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in people with chronic health conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28:1159–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215514536210.

Sargent GM, Forrest LE, Parker RM. Nurse delivered lifestyle interventions in primary health care to treat chronic disease risk factors associated with obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2012;13:1148–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01029.x.

Bossen D, Veenhof C, Dekker J, de Bakker D. The effectiveness of self-guided web-based physical activity interventions among patients with a chronic disease: a systematic review. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11:665–77. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2012-0152.

McGrane N, Cusack T, O’Donoghue G, Stokes E. Motivational strategies for physiotherapists. Phys Ther Rev. 2014;19:136–42. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743288X13Y.0000000117.

Zenko Z, Ekkekakis P, Ariely D. Can you have your vigorous exercise and enjoy it too? Ramping intensity down increases postexercise, remembered, and forecasted pleasure. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2016;38:149–59. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2015-0286.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

Loprinzi PD. Physical activity is the best buy in medicine, but perhaps for less obvious reasons. Prev Med. 2015;75:23–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.033.

Lippke S, Ziegelmann JP. Theory-based health behavior change: developing, testing, and applying theories for evidence-based interventions. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:698–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00339.x.

Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9:323–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.941722.

Rhodes RE, McEwan D, Rebar AL. Theories of physical activity behaviour change: a history and synthesis of approaches. Psychol Sport Exercise. 2018;42:100–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.11.010.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6.

King AC, Whitt-Glover MC, Marquez DX, Buman MP, Napolitano MA, Jakicic J, et al. Physical activity promotion: highlights from the 2018 physical activity guidelines advisory committee systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:1340–53. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001945.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of the Bewegungsförderung im Alltag (Physical Activity Promotion in Daily Living) working group who made a valuable contribution to the recommendations through their constructive suggestions and feedback.

Funding

The development of the national recommendations for physical activity and physical activity promotion has been funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health (ZMVI 5 2514FSB-200). The ministry was not involved in the writing of this manuscript or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This work summarises aspects of the development of the national recommendations for physical activity and physical activity promotion. WG, KA, SM, and KP are members of the Committee for the Development of the German Recommendations on Physical Activity and Physical Activity Promotion. WG and KA conceptualised this paper. WG and KP are responsible for the methods and results related to the German recommendations for physical activity; KA, MW, SM, and KP are responsible for the methods and results related to the German recommendations for physical activity promotion; MW, KA, and WG wrote the draft of this manuscript; all authors revised the draft of the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Criteria for Quality Assessment and Content Analysis of Physical Activity Recommendations. This file lists the 28 criteria used to assess methodological quality and analyse motion-related content.

Additional file 2.

Quality checklist for the systematic reviews of reviews regarding the effectiveness/efficacy of PA promoting interventions. This file lists the criteria used to evaluate the papers reporting PA promotion interventions with regard to their effectiveness/efficacy.

Additional file 3.

Quality ratings of the physical activity recommendations and additional ressources (meta-analysis and reviews on physical activity recommendations) that were additional included without explicit quality ratings for seven noncommunicable diseases. This file lists the retrieved articles and their quality ratings leading to the decision on which articles the German Recommendations for Physical Activity for Adults with NCD were developed.

Additional file 4.

Quality rating of the reviews for developing the German Recommendations for PA Promotion. This table contains the quality rating of the reviews used to develop the German Recommendations for PA promotion.

Additional file 5.

Quality criteria for the conceptualization, implementation and evaluation of PA promoting interventions. This table lists the general quality criteria for PA promotion interventions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Geidl, W., Abu-Omar, K., Weege, M. et al. German recommendations for physical activity and physical activity promotion in adults with noncommunicable diseases. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 17, 12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-0919-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-0919-x