Abstract

Background

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to investigate whether behaviour change interventions promote changes in physical activity and anthropometrics (body mass, body mass index and waist circumference) in ambulatory hospital populations.

Methods

Randomised controlled trials were collected from five bibliographic databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and PsycINFO). Meta-analyses were conducted using change scores from baseline to determine mean differences (MD), standardised mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach was used to evaluate the quality of the evidence.

Results

A total of 29 studies met the eligibility criteria and 21 were included in meta-analyses. Behaviour change interventions significantly increased physical activity (SMD: 1.30; 95% CI: 0.53 to 2.07, p < 0.01), and resulted in significant reductions in body mass (MD: -2.74; 95% CI: − 4.42 to − 1.07, p < 0.01), body mass index (MD: -0.99; 95% CI: − 1.48 to − 0.50, p < 0.01) and waist circumference (MD: -2.21; 95% CI: − 4.01 to − 0.42, p = 0.02). The GRADE assessment indicated that the evidence is very uncertain about the effect of behaviour change interventions on changes in physical activity and anthropometrics in ambulatory hospital patients.

Conclusions

Behaviour change interventions initiated in the ambulatory hospital setting significantly increased physical activity and significantly reduced body mass, body mass index and waist circumference. Increased clarity in interventions definitions and assessments of treatment fidelity are factors that need attention in future research.

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42020172140.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic diseases are leading causes of ill health worldwide [1]. Modifiable risk factors such as insufficient physical activity (PA), poor diet, and obesity are associated with an increased risk for chronic disease [2] and, due to medical improvements, individuals are living with chronic disease for longer periods [3, 4]. Increased survival amongst people with chronic disease results in a higher prevalence of morbidity, and lower quality of life [4]. As a result, secondary prevention has become important for chronic disease management globally [5].

Secondary prevention aims to reduce the impact of chronic disease through early detection and treatment. Behaviour change as a secondary prevention strategy is emerging as a way to mitigate the impact of disease and slow down disease progression [6]. Hospitals are important settings for the delivery of secondary prevention programs given their unique access to members of the local community who might benefit [7]. Hospital attendees are not necessarily registered with a GP and may not be actively engaged with community health promotion services [7], but because their health is already compromised, these individuals can be readily motivated to engage with lifestyle behaviour changes [8]. Behaviour change interventions are advocated as the first-line approach to behavioural risk factor management [9].

Results from recent meta-analyses indicate that secondary prevention behaviour change interventions result in positive effects in PA [10, 11], anthropometrics [11] and cardiovascular health [12]. These reviews included studies from hospital settings, though many studies recruited patients from the inpatient setting [10, 11]. Contextual differences exist in recruiting individuals for behaviour change interventions from the admitted versus ambulatory hospital setting [13, 14].

In the inpatient setting, patients are removed from their home environments, often suffering from a serious condition, and are potentially confined to their bed or the hospital room [14]. Being hospitalised has been identified as a major life event, increasing the likelihood of engaging in recommended care [15]. The inpatient environment imposes unique constraints on individuals, including their perception of autonomy of their care [13]. Consequently, the decision to initiate health behaviour change is potentially impacted by the inpatient setting [13].

Ambulatory hospital patients, on the other hand, engage in care under different circumstances. These individuals are community-dwelling, and maintain more autonomy over their care, including decisions regarding the treatment plan, or when they can expect to see the doctor next [16]. The delivery of preventive health care in the ambulatory hospital setting should be targeted, patient-centred, and characterised by interventions that support people with chronic disease risk factors and should include self-management support wherever possible [17]. Knowledge of the impact of behaviour change interventions on ambulatory hospital patients might allow prioritising preventive interventions in the ambulatory hospital setting for the prevention and management of chronic disease. To the best of our knowledge, no review has examined the effect of behaviour change interventions that address changes in PA and anthropometrics in non-admitted secondary care patients. Therefore, the aim of this review was to examine the effect of behaviour change interventions on changes and maintenance on PA, and anthropometrics, initiated in the ambulatory hospital setting only.

Research question

Do behaviour change interventions result in positive changes and maintenance in PA and anthropometrics in adults attending ambulatory hospital clinics?

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [18] (Additional file 1). This review was registered with PROSPERO (registration ID: CRD42020172140).

Data sources and search strategies

To avoid duplication, a search was undertaken in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PubMed Clinical Queries and PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews to confirm that no similar systematic reviews or protocols have been conducted. Eligible studies were collected (from inception until May 2020) using computer-based searches in MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) electronic databases. Database-specific search strategies were developed with the guidance of professional clinical librarians. The database searches were performed using three main concepts: ambulatory secondary hospital care, lifestyle behaviour change interventions and outcomes (PA and anthropometric measures). For each main concept relevant related terms and keywords were included in the sensitive search (search details for MEDLINE are presented in Additional file 2).

Two additional steps were undertaken to ensure the comprehensiveness of our search. Firstly, searches were undertaken in clinical trial registries, including ClinicalTrials.gov, EU Clinical Trials Register, Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trial Registry Platform to source relevant ongoing and unpublished trials. Secondly, we performed a snowball search on reference lists, and grey literature databases.

Eligibility criteria

The term behaviour change interventions is used to define coordinated activities designed to change specified behaviour outcomes [19]. For the purpose of this review, we included behaviour change interventions that specifically aimed to elicit changes in anthropometrics and/or PA changes through the use of behaviour modification components and strategies. Inclusion criteria to select studies were: 1) Study population: adult (aged 18 or older) ambulatory hospital patients; 2) Types of studies: peer-reviewed randomised controlled trials regarding a behaviour change intervention compared to a control intervention or usual care comparison group. The behaviour change intervention could be a single intervention or a multi-component intervention, but needed to include at least one session that was delivered in a 1:1 format (delivered in person, via the phone or telehealth) because of the importance of an individualised approach to self-management [20]; 3) Primary outcomes: PA, anthropometric measures – body mass, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC). Due to the clinical relevance of changes in body mass, BMI and WC, an a priori decision was made to undertake an meta-analysis on each outcome individually [21, 22]. Behavioural science highlights the need to draw the distinction between initial behaviour change and behaviour change maintenance [23]. To establish the maintenance effect of interventions, studies that included a follow-up duration of less than 12 weeks were excluded.

Studies were included that reported any of the following physical activity outcome measures: changes in daily steps, METs per week (METs/wk) or minutes per day/week of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) measured subjectively (e.g., self-report) or objectively at baseline and post intervention.

Study selection

Studies were entered into Review Manager (Version 5.3; The Cochrane Collaboration, Denmark) and duplicates were removed. Screening was carried out using Covidence (Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). Two authors independently screened title/abstracts and full text. Studies were systematically excluded when they did not meet the pre-specified inclusion criteria. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion, or where required with consensus of a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers. Data extraction was performed with the aid of a predesigned and piloted data collection form. For each study, the reviewers extracted information with respect to study characteristics (type of study, population description, focused disease or condition); study participants (sample size, demographics); methods (intervention duration, type and frequency, fidelity blinding, amount of intervention groups, number of included participants, the number of individuals that were randomised and analysed); the professional background of the person delivering the intervention); and outcome variables (outcome definition, unit of measurement, time points measured and reported). Continuous data including, means, standard deviations and the sample size numbers were extracted. When information was unclear, insufficient or missing, the authors of trials were contacted for clarifications and additional results. Where standard deviations were not available, measures of variance were estimated from the standard error of a mean, confidence intervals or p-values according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions the Cochrane Collaboration [19]. When data were presented as median and interquartile range, the mean and standard deviation were estimated using the formula from Hozo et al. [24].

Study quality assessment

The risk of bias of the included studies was assessed by two reviewers independently using the Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool [25]. The following methodological criteria were assessed: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other potential threats to validity [25]. Each of these criteria were judged and classified as ‘low risk’, ‘high risk’ or ‘unclear risk’ of bias.

The overall strength of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [26] system through the GRADEpro 3.6 software (GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software]; McMaster University, USA). Quality of evidence for meta-analyses began at the high level and was downgraded to lower levels of evidence when risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision or publication bias were present. Publication bias was examined by Egger test [27].

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations of change scores for both intervention and control groups were included in one of the extracted studies [28]. Using these change data, the correlation coefficients were calculated for the intervention group (r = 0.81) and control group (r = 0.80), with an average r of 0.80 [28]. For all included studies, the standard deviation of change scores from baseline were calculated using a correlation coefficient of 0.8 [25], and entered directly into Review Manager 5.3 (Version 5.3; The Cochrane Collaboration, Denmark) for analysis. Analyses based on changes from baseline are more efficient and powerful than comparison of final values through the removal of between-person variability [25]. The mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for anthropometric outcomes. For PA outcomes, standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% CIs were calculated using Review Manager 5.3 as the mean difference divided by the pooled standard deviation [25]. Due to the heterogeneity in the study interventions and populations, meta-analyses were conducted using a random effects model [25]. In keeping with recommendations, an effect size of 0.2 was considered small, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 or more was considered large [29]. The effect of heterogeneity of each summary effect size was quantified using a chi-squared test and the I2 statistic, in which the boundary limits 25, 50, and 75% were designated as a low, moderate, and high heterogeneity value, respectively [25].

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

All analyses were repeated with correlations set at lower (0.50) and higher (1.0) r values than the calculated value of 0.80. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess heterogeneity of the studies and to evaluate the robustness of the results. Each study was individually removed to evaluate the effect of that study on the summary estimates.

Subgroup analyses were performed to investigate the essential elements in designing effective behaviour change interventions in the ambulatory hospital setting. The subgroup analyses included the study population, follow-up duration, objective or self-reported measurements, the duration of intervention, and the dose of the intervention. The duration of intervention was classified as short term (≤ 3 months) or longer term if ≥4 months [30]. The reporting of the length of intervention sessions was poor in many of the included studies. As a result the intervention dose quantified in this review is through the number of sessions. This intervention dose was categorised as low intensity (≤ 6 sessions), medium intensity (7–12 sessions) or high intensity (≥ 13 sessions) [31].

Results

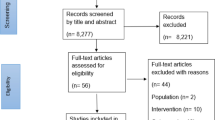

Following de-duplication, 2984 studies were screened. The PRISMA diagram for the screening is shown in Fig. 1. Twenty-nine full-text articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in qualitative (n = 29) and quantitative (n = 21) syntheses (Table 1) [28, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Included studies were published over a 17-year period from 2003 to 2020. The studies were performed in 14 different countries, with the largest representation from the United States (n = 6), Holland (n = 4) and Australia (n = 4). Populations within the included studies represented various health conditions including impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (n = 10) [32, 36, 37, 40, 48, 49, 53, 55, 56, 59], cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (n = 10) [28, 35, 38, 39, 41, 45,46,47, 50, 51], overweight/obesity (n = 5) [42, 44, 52, 54, 57], insufficiently physically active (n = 1) [34], Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (n = 1) [58], cerebrovascular disease (n = 1) [33], and cancer (n = 1) [43].

Study characteristics

The behaviour change interventions in the included studies varied in intervention duration from 4 to 416 weeks. With the exclusion of Sone et al. [55], which used a low grade intervention over 8 years, the adjusted intervention duration was 32 ± 24 weeks. The intervention duration was 26 weeks or greater in 66% of the included studies. Follow-up duration varied amongst the studies: 5 studies had a 3-month follow-up [38, 42, 47, 48, 56], 1 study had a 4-month follow-up [59], 10 studies had a 6-month follow-up [34, 35, 37, 40, 43, 46, 51, 52, 54, 57], 2 studies had a 9-month follow-up [28, 39], 4 studies had a 12-month follow-up, and the remaining 7 studies varied between 15 months and 8 years of follow-up [33, 44, 45, 49, 53, 55, 58].

The intervention components used in the included studies varied. All of the included studies had at least one component that was delivered 1:1. The underlying theory informing the behaviour change intervention and the behaviour change techniques used are detailed in Table 1. For nine studies, the main focus of the intervention was on increasing PA [28, 34, 38, 43, 47, 48, 51, 54, 58]. Changes in anthropometrics was the primary focus in four studies [40, 44, 52, 54].

For PA outcomes, objective measurement was used in 8 studies using accelerometers, pedometers and objective measurement of exercise capacity [34, 37,38,39, 41, 43, 51, 58]. Self-reported instruments were used in the other 18 studies [28, 33, 35, 36, 40, 41, 44,45,46,47,48, 50, 52,53,54,55,56,57]. The measures of anthropometrics in the studies included body mass [28, 32, 34, 35, 44, 52,53,54, 57], BMI [28, 32,33,34,35,36, 39, 40, 50, 52,53,54,55, 57, 59] and WC [34, 35, 40, 50, 53]. Objective measurement of anthropometrics was used in 15 of the studies [32, 34, 39, 44, 46, 47, 49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57], with self-reported methods used in the remaining 3 studies [37, 45, 59].

The professional background of the persons delivering the interventions included community health workers [36], dietitians [37, 38, 40, 50, 53, 55], exercise counsellors [51, 58], exercise scientists [48, 50], graduate level therapists [41], health professionals [32], health educators [38, 39], lifestyle coaches [44], nurses [28, 33, 35, 45, 55], physicians [33, 55], physiotherapists [34, 53, 55], psychologists [46], researchers [56, 57, 59], and therapists [43].

Risk of bias

The risk of bias assessment for all studies is detailed in Fig. 2. In trials involving behaviour change interventions the blinding of participants is extremely difficult to undertake. As a result, all studies were judged to have a high of risk of performance bias (lack of blinding of participants and personnel). Twelve studies were judged to have a high risk of attrition bias, and four studies were rated as unclear. Seven of the included studies reported blinding of the outcome assessors (detection bias), whereas the majority of the studies did not adequately report blinding of the outcome assessors (n = 18). Five of the included studies were judged as a high risk of selection bias due to the lack of detail regarding the allocation concealment. Fifteen studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias due to the lack of information provided on the random sequence generation. The individual risk of bias assessment is included in Additional file 3.

GRADE assessment

The overall certainty of evidence for the effectiveness of behaviour change interventions for changes in PA and anthropometrics in adults attending ambulatory hospital clinics is presented in Table 2. The certainty of evidence for the meta-analysis stratified by follow-up duration and for studies with a low risk of bias are presented in Additional file 4. In addition, the GRADE quality assessments are presented in Additional file 5.

Effects of behaviour change interventions on changes in physical activity

Thirteen of the 29 included studies provided PA data for the intervention and control groups at the post-intervention follow-up, and were included in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis for behaviour change interventions versus standard care for change in PA demonstrated a significant effect in favour of the intervention (SMD: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.45 to 1.48, p < 0.01, Fig. 3) [28, 34, 38, 39, 41, 43, 44, 47, 50, 52, 54, 57, 58].

Subgroup analyses indicated that behaviour change interventions resulted in a significant increase in PA when the follow-up lasted for 6 months or less (SMD: 1.30; 95% CI: 0.53 to 2.07, p < 0.01, Fig. 3) [34, 38, 43, 44, 47, 52, 54, 57]. Behaviour change interventions with a follow-up of greater than 6 months demonstrated a non-significant effect in favour of the intervention (SMD: 0.43; 95% CI: − 0.07 to 0.93, p = 0.09, Fig. 3) [28, 39, 41, 50, 58]. Behaviour change interventions may increase PA in ambulatory hospital patients but the evidence is very uncertain.

Effects of behaviour change interventions on changes in body mass

Nine studies provided data on changes in body mass for the experimental and control groups at the post-intervention follow-up, and were included in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis for behaviour change interventions versus standard care for change in body mass demonstrated a significant effect in favour of the intervention (MD: -2.74; 95% CI: − 4.42 to − 1.07, p < 0.01, Fig. 4) [28, 32, 34, 35, 44, 52,53,54, 57].

Subgroup analyses indicated that behaviour change interventions resulted in a significant changes in body mass when follow-up measurement was 6 months and under (MD: -3.15; 95% CI: − 5.96 to − 0.34, p = 0.03, Fig. 4), and greater than 6 months (MD: -2.37; 95% CI: − 4.40 to − 0.35, p = 0.02, Fig. 4). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of behaviour change interventions on changes in mass in ambulatory hospital patients.

Effects of behaviour change interventions on changes in BMI

Fifteen studies provided data on changes in BMI for the experimental and control groups at the post-intervention follow-up and were included in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis for behaviour change interventions versus standard care for change in BMI demonstrated a significant effect in favour of the intervention (MD: -0.99; 95% CI: − 1.48 to − 0.50, p < 0.01, Fig. 5) [28, 32,33,34,35,36, 39, 40, 50, 52,53,54,55, 57, 59].

The behaviour change interventions demonstrated significant changes in BMI when follow-up measurement was 6 months and under (MD: -1.55; 95% CI: − 2.58 to − 0.53, p < 0.01, Fig. 5), and greater than 6 months (MD: -0.75; 95% CI: − 1.35 to − 0.16, p = 0.01, Fig. 5). Behaviour change interventions may decrease BMI in ambulatory hospital patients but the evidence is very uncertain.

Effects of behaviour change interventions on changes in waist circumference

Five studies provided data on changes in WC for the experimental and control groups at the post-intervention follow-up and were included in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis for behaviour change interventions versus standard care for change in WC demonstrated a significant effect in favour of the intervention (MD: -2.21; 95% CI: − 4.01 to − 0.42, p = 0.02, Fig. 6) [34, 35, 40, 50, 53].

The behaviour change interventions demonstrated significant changes in WC when follow-up measurement was 6 months and under (3 studies, 194 participants, MD, − 3.91, 95% CI, − 5.96 to − 1.85, p < 0.01, Fig. 6), but not when the follow-up was greater than 6 months (MD: -0.66; 95% CI: − 2.88 to 0.95, p = 0.42, Fig. 6). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of behaviour change interventions on changes in WC in ambulatory hospital patients. The one exception was the analysis for WC change when follow-up measurement was 6 months and under, in which case the evidence suggests that behaviour change interventions results in a slight reduction in WC in ambulatory hospital patients.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

Sensitivity analyses of the imputed correlation coefficients revealed that effect sizes remained statistically significant, and within the 95% confidence intervals at the imputed r of 0.8 (Table 3). Statistically significant changes remained for all outcomes at the inputed r of 1.0 and 0.5. In the low risk of bias analyses, behaviour change interventions exhibited significant beneficial effects in PA, body mass and BMI. Subgroup analyses demonstrated significant changes in body mass and BMI for individuals with cardiovascular diseases, and significant changes in BMI for individuals with type 2 diabetes/impaired glucose tolerance (Table 3). Larger effect sizes were observed for PA and BMI changes when objective measurement was used. Larger effect sizes were observed for changes in body mass when self-reported measurement was used. No subgroup analysis could be conducted on changes in WC between objective and self-reported measures.

Interventions with a short-term duration demonstrated significant effects for changes in PA, body mass, BMI and WC (Table 3). Interventions with a longer-term duration demonstrated significant effects for changes in body mass and BMI only (Table 3). In terms of intervention dose, interventions categorised as low intensity demonstrated significant effects for changes in body mass and WC (Table 3). Interventions categorised as medium intensity demonstrated significant effects for changes in PA and body mass (Table 3). Interventions categorised as high intensity demonstrated significant effects for changes in BMI (Table 3). No subgroup analysis could be conducted on changes in WC between dose of intervention. The moderate to high heterogeneity found in the primary meta-analyses was consistent across the majority of sensitivity and subgroup analyses.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analyses provides evidence to support the use of behaviour change interventions for changes in PA and anthropometrics, initiated in the ambulatory hospital setting. The effect sizes were large for PA and moderate for anthropometric outcomes. These positive results are important as even small positive changes in PA and anthropometrics can deliver beneficial health benefits [60]. The moderate to large effect sizes demonstrated here are likely to deliver important health outcomes for ambulatory hospital patients [60]. Patients attending secondary care hospital clinics are more likely than the general population to have preventable chronic disease due to risk factors such as insufficient PA or overweight and obesity [61]. Behaviour change interventions aimed at changes in PA and anthropometrics can go towards addressing health risks in this population [62]. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of results for all outcomes were moderate to high, and the GRADE assessment indicated that the evidence is very uncertain about the effect of behaviour change interventions on changes in PA and anthropometrics.

The meta-analysis of 13 randomised controlled trials for behaviour change interventions versus standard care for changes in PA demonstrated a significant large effect (d = 0.96) in favour of the intervention. The effect size is larger than those reported for PA interventions aiming to increase PA in older adults (d = 0.26) [63], chronically ill adults (d = 0.45) [64], healthy inactive adults (d = 0.32) [65] and young and middle aged adults (d = 0.32) [66], but similar to that reported for behaviour change interventions targeting individuals at risk of cardiovascular disease [10, 11]. The heterogeneity of both interventions and outcome measures, and the wide confidence intervals observed in the included studies contributed to the downgrading of the certainty about the results to very low. Despite the low level of certainty, it is encouraging to see a significant positive intervention effect across the diverse clinical populations with the included measures of PA participation.

When stratified by follow-up duration, the analyses of the effect of behaviour change interventions on changes in PA demonstrated a significant increase in PA when the follow-up lasted for 6 months sessions or less. Interventions with a follow-up of greater than 6 months demonstrated a non-significant effect in favour of the intervention. Samdal et al., (2017) found that strategies such as motivational interviewing and goal setting are effective for assisting individuals in initiating PA behaviour change [67]. Cognitive strategies such as problem solving and relapse prevention, on the other hand, promote changes in cognition, PA beliefs and influence behaviour change maintenance [68]. Some of the most common strategies used in the studies included in this review were motivational interviewing, goal setting and general counselling/health coaching. These strategies are all acknowledged as important theoretical constructs for successful behaviour change [69]; however, very few of the included studies clearly demarcated the use of strategies for PA maintenance, which could have impacted the effect size over the longer term follow-up. Only a small number of the included studies aimed to engage participants in existing community resources. Referrals to specific community programs, such as walking groups, strength training, and exercise for adults, have shown to have a positive effect on longer-term PA behaviour [69].

The meta-analyses of behaviour change interventions versus standard care for changes in anthropometric outcomes demonstrated significant positive effects in body mass, BMI and WC. Significant reductions in body mass, BMI and WC were found when the follow-up lasted for 6 months or less. Significant favourable changes in body mass and BMI were found when the follow-up lasted for greater than 6 months. The increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity over recent decades have been a major public health concern [70]. Overweight and obesity not only have a direct impact on morbidity, but contribute significantly towards further metabolic conditions, including insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes [71]. Behaviour change interventions, predominantly focusing on changes in PA and anthropometrics, are the central tenets of prevention programs needed to address overweight and obesity prevalence [72]. This review adds to the evidence base to support the use of behaviour change interventions to influence anthropometric changes in the ambulatory hospital setting.

The 2.74 kg (95% CI: − 4.42 to − 1.07) reduction in body mass found in this meta-analysis compares to similar reductions of 3.77 kg (95% CI: − 4.55 to − 2.99) [73] and 2.12 kg (95% CI: − 2.61 to − 1.63) [74] found in behaviour change interventions for people at high risk for diabetes, and in nutritional education programs with a specific focus on weight loss (− 2.07 kg; 95% CI: − 1.52 to − 2.62). The mean reduction in BMI of 0.99 kg/m2 (95% CI: − 1.48 to − 0.50) found in this meta-analysis lies between the results from studies in secondary prevention behaviour change interventions, being − 0.16 kg/m2 (95% CI: − 0.62 to 0.31) [10] and − 1.80 kg/m2 (95% CI: − 2.62 to − 0.99) [11]. The significant decrease in body mass and BMI over the longer-term follow-up is noteworthy given the mean age of the individuals in the analyses was 57. High proportions of middle aged individuals continue to gain weight each year [75]. The magnitude of improvements observed for changes in anthropometrics found in this review are likely to be clinically significant. Favourable changes in anthropometrics are associated with decreased risk for cardiovascular events [76], type 2 diabetes [76, 77] and some cancers [77].

Implications for practice

Previous research has shown that experiencing health events such as hospital appointments can be the catalyst for changes in behaviour [15, 78]. Ambulatory hospital patients represent an ideal population to intervene with to lessen the risk of developing serious health conditions. Incorporating the use of behaviour change interventions to increase PA in adults attending ambulatory hospital clinics aligns with the 2020 World Health Organization guidelines on PA and sedentary behaviour, which indicate the importance of PA for individuals with chronic conditions [79]. The current analysis incorporates a wide range of participant populations attending ambulatory hospital clinics, ranging from younger to older adults, as well as individuals with health risk factors to individuals with diagnosed chronic conditions. Hospital patients have indicated that they would like the healthcare system to provide guidance on behaviour change and healthy lifestyles [80]. Patients and public health at large might benefit from hospitals shifting their focus from predominantly curative care to a position of more holistic health promotion [81, 82].

Hospitals considering integrating behaviour change interventions into routine care may be encouraged that the delivery of short duration interventions results in statistically significant changes in PA, body mass, BMI and WC for hospital patients. The subgroup analyses provide some indication of the effect of intervention dose on PA and anthropometric changes, with significant changes observed for medium and high intensity interventions. Behaviour change interventions providing a higher number of sessions have been demonstrated to increase self-management skills, which may result in the significant outcomes observed for medium and high intensity interventions [83, 84]. Another potential advantage highlighted in this review was the range of health professionals that were able to deliver the behaviour change intervention. The diversity in clinicians might be advantageous when applying the intervention across differing sectors of the ambulatory hospital setting.

Limitations

This review has a number of limitations. The wide range of PA measures used within the interventions suggest that caution should be applied when interpreting the translatability of these results. Additionally, only 4 of the studies in the PA meta-analysis used objective measurement [34, 38, 43, 58]. Social desirability bias can lead to over-reporting of PA levels in self-reported measures [85]. Although the majority of self-report questionnaires were based on valid and reliable measures, objective measurements have demonstrated a higher degree of reproducibility and validity for quantifying duration and intensity of PA [86]. The effect size calculated from studies that used objectively measured PA was higher than the overall effect size observed for PA change (Table 3), which improves confidence in the effectiveness of behaviour change interventions to increase PA in ambulatory hospital settings.

The meta-analyses included studies with small sample sizes, and differences in the duration of interventions. The review also included studies with heterogeneous intervention components including differences in the frequency and duration of the sessions, and differences in the professionals providing the intervention. The heterogeneity also existed in the delivery format, including face-to-face, telephone calls and group counselling delivery. This heterogeneity makes the independent contribution of any of the intervention components, or a combination of these factors, difficult to establish, and partially explains the moderate to high heterogeneity of the meta-analyses. The moderate to high heterogeneity was reported in the majority of sub-group analyses, indicating a consistency of results across the examination of the different components of the interventions. Behaviour change interventions tend to exhibit both clinical and methodological diversity, often resulting in statistical heterogeneity within the meta-analyses [87]. Indeed, almost one third of meta-analyses have been shown to result in moderate to high heterogeneity [87]. Finally, only 5 of the 29 included studies reported on intervention fidelity [33, 34, 36, 41, 44]. Without a clear measurement of fidelity, reports of the effectiveness of interventions must be interpreted cautiously, as the possibility that the intervention was not delivered as intended cannot be ruled out [65].

Conclusion

This review indicates that behaviour change interventions resulted in large improvements in PA, and moderate changes in anthropometric outcomes in adults presenting to ambulatory hospital clinics. The results indicate the value of behaviour change interventions for mitigating chronic disease risk factors, and supports the implementation of behaviour change interventions in ambulatory secondary care clinics. The heterogeneity in study populations, reported outcomes, and intervention components downgraded the certainty of the evidence, and prevents the drawing of firmer conclusions from the evidence provided. In order to improve the translation of these findings into clinical practice, future studies of behaviour change interventions should include clearly defined interventions and assessments of treatment fidelity.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- IGT:

-

Impaired Glucose Tolerance

- MD:

-

Mean Difference

- PA:

-

Physical Activity

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SMD:

-

Standardised Mean Difference

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 Diabetes

- WC:

-

Waist Circumference

References

World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014: . No. WHO/NMH/NVI/15.1. World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-status-report-2014/en/.

Strong K, Mathers C, Leeder S, Beaglehole R. Preventing chronic diseases: how many lives can we save? Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1578–82.

Chen H, Chen G, Zheng X, Guo Y. Contribution of specific diseases and injuries to changes in health adjusted life expectancy in 187 countries from 1990 to 2013: retrospective observational study. BMJ. 2019;364:l969.

Solé-Auró A, Alcañiz M. Are we living longer but less healthy? Trends in mortality and morbidity in Catalonia (Spain), 1994–2011. Eur J Ageing. 2015;12(1):61–70.

Germano G, Hoes A, Karadeniz S, Mezzani A, Prescott E, Ryden L, Scherer M, Syvanne M, Reimer WJ, Vrints C, Zamorano JL. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1635–701.

Schmidt H. Chronic disease prevention and health promotion. InPublic health ethics: cases spanning the globe. Cham: Springer; 2016. p. 137–76.

Gate L, Warren-Gash C, Clarke A, Bartley A, Fowler E, Semple G, Strelitz J, Dutey P, Tookman A, Rodger A. Promoting lifestyle behaviour change and well-being in hospital patients: a pilot study of an evidence-based psychological intervention. J Public Health. 2016;38(3):e292–300.

Lawson PJ, Flocke SA. Teachable moments for health behavior change: a concept analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(1):25–30.

Lindner H, Menzies D, Kelly J, Taylor S, Shearer M. Coaching for behaviour change in chronic disease: a review of the literature and the implications for coaching as a self-management intervention. Aust J Prim Health. 2003;9(3):177–85.

Lawlor ER, Bradley DT, Cupples ME, Tully MA. The effect of community-based interventions for cardiovascular disease secondary prevention on behavioural risk factors. Prev Med. 2018;114:24–38.

Sisti LG, Dajko M, Campanella P, Shkurti E, Ricciardi W, De Waure C. The effect of multifactorial lifestyle interventions on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials conducted in the general population and high risk groups. Prev Med. 2018;109:82–97.

De Waure C, Lauret GJ, Ricciardi W, Ferket B, Teijink J, Spronk S, Hunink MM. Lifestyle interventions in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(2):207–16.

Bickmore TW, Pfeifer LM, Jack BW. Taking the time to care: empowering low health literacy hospital patients with virtual nurse agents. InProceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems; 2009. p. 1265–74.

Mishra SR, Haldar S, Pollack AH, Kendall L, Miller AD, Khelifi M, Pratt W. “Not Just a Receiver” Understanding Patient Behavior in the Hospital Environment. InProceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2016. p. 3103–14.

Allender S, Hutchinson L, Foster C. Life-change events and participation in physical activity: a systematic review. Health Promot Int. 2008;23(2):160–72.

Kendall L, Mishra SR, Pollack A, Aaronson B, Pratt W. Making background work visible: opportunities to address patient information needs in the hospital. InAMIA annual symposium proceedings, vol. 2015; 2015. p. 1957. American Medical Informatics Association.

Primary Health Care Advisory Group (Australia). Better Outcomes for People with Chronic and Complex Health Conditions Through Primary Health Care: Discussion Paper. Department of Health; 2015.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42.

Pearson ML, Mattke S, Shaw R, Ridgely MS, Wiseman SH. Patient self-management support programs: an evaluation. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. p. 08–011.

Ryan DH, Yockey SR. Weight loss and improvement in comorbidity: differences at 5, 10, 15%, and over. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):187–94.

Huxley R, Mendis S, Zheleznyakov E, Reddy S, Chan J. Body mass index, waist circumference and waist:hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular risk--a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Nut. 2010;64(1):16–22.

Kwasnicka D, Dombrowski SU, White M, Sniehotta F. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: a systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(3):277–96.

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5(1):13.

Higgins JP. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1. 0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. www.cochrane-handbook.org. 2011.

Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, Nasser M, Meerpohl J, Post PN, Kunz R, Brozek J. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):719–25.

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Alsaleh E, Windle R, Blake H. Behavioural intervention to increase physical activity in adults with coronary heart disease in Jordan. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–1.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral. Sciences 2nd edn. Hillsdale: Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Gal R, May AM, van Overmeeren EJ, Simons M, Monninkhof EM. The effect of physical activity interventions comprising Wearables and smartphone applications on physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine – Open. 2018;4(1):42.

Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Edu Res. 2003;18(2):237–56.

Aas AM, Bergstad I, Thorsby PM, Johannesen Ø, Solberg M, Birkeland KI. An intensified lifestyle intervention programme may be superior to insulin treatment in poorly controlled type 2 diabetic patients on oral hypoglycaemic agents: results of a feasibility study. Diabet Med. 2005;22(3):316–22.

Ahmadi M, Laumeier I, Ihl T, Steinicke M, Ferse C, Endres M, Grau A, Hastrup S, Poppert H, Palm F, Schoene M. A support programme for secondary prevention in patients with transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke (INSPiRE-TMS): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(1):49–60.

Barrett S, Begg S, O'Halloran P, Kingsley M. Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy can increase physical activity and improve health of adult ambulatory care patients in a regional hospital: the Healthy4U randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1166.

Cakir H, Pinar R. Randomized controlled trial on lifestyle modification in hypertensive patients. West J Nurs Res. 2006;28(2):190–209.

Carrasquillo O, Lebron C, Alonzo Y, Hua L, Chang A, Kenya S, Li H. Effect of a community health worker intervention among Latinos with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: the Miami healthy heart initiative randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):948–54.

Cheung NW, Blumenthal C, Smith BJ, Hogan R, Thiagalingam A, Redfern J, Barry T, Cinnadaio N, Chow CK. A pilot randomised controlled trial of a text messaging intervention with customisation using linked data from wireless wearable activity monitors to improve risk factors following gestational diabetes. Nutrients. 2019;11(3):590.

Duscha BD, Piner LW, Patel MP, Craig KP, Brady M, McGarrah RW, Chen C, Kraus WE. Effects of a 12-week mHealth program on peak VO2 and physical activity patterns after completing cardiac rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J. 2018;199:105–14.

Elkoustaf RA, Aldaas OM, Batiste CD, Mercer A, Robinson M, Newton D, Burchett R, Cornelius C, Patterson H, Ismail MH. Lifestyle interventions and carotid plaque burden: a comparative analysis of two lifestyle intervention programs in patients with coronary artery disease. Perm J. 2019;23(18):196. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18.196.

Fappa E, Yannakoulia M, Ioannidou M, Skoumas Y, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Telephone counseling intervention improves dietary habits and metabolic parameters of patients with the metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Diabet Stud. 2012;9(1):36–45.

Freedland KE, Carney RM, Rich MW, Steinmeyer BC, Rubin EH. Cognitive behavior therapy for depression and self-Care in Heart Failure Patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Int Med. 2015;175(11):1773–82.

Gade H, Hjelmesaeth J, Rosenvinge JH, Friborg O. Effectiveness of a cognitive behavioral therapy for dysfunctional eating among patients admitted for bariatric surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Obes. 2014;2014:127936.

Goedendorp MM, Peters MEW, Gielissen MFM, Witjes JA, Leer JW, Verhagen CAH, Bleijenberg G. Is increasing physical activity necessary to diminish fatigue during Cancer treatment? Comparing cognitive behavior therapy and a brief nursing intervention with usual Care in a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Oncologist. 2010;15(10):1122–32.

Goodwin PJ, Segal RJ, Vallis M, Ligibel JA, Pond GR, Robidoux A, Blackburn GL, Findlay B, Gralow JR, Mukherjee S, et al. Randomized trial of a telephone-based weight loss intervention in postmenopausal women with breast cancer receiving letrozole: the LISA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(21):2231–9.

Harting J, Van Assema P, Van Limpt P, Gorgels T, Van Ree J, Ruland E, Vermeer F, De Vries NK. Effects of health counseling on behavioural risk factors in a high-risk cardiology outpatient population: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2006;13(2):214–21.

Ijzelenberg W, Hellemans IM, van Tulder MW, Heymans MW, Rauwerda JA, van Rossum AC, Seidell JC. The effect of a comprehensive lifestyle intervention on cardiovascular risk factors in pharmacologically treated patients with stable cardiovascular disease compared to usual care: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disor. 2012;12:71.

Kim KA, Hwang SY. Effects of a daily life-based physical activity enhancement program for middle-aged women at risk for cardiovascular disease. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2019;49(2):113–25.

Kirk AF, Mutrie N, MacIntyre PD, Fisher MB. Promoting and maintaining physical activity in people with type 2 diabetes. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(4):289–96.

Kosaka K, Noda M, Kuzuya T. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: a Japanese trial in IGT males. Diabetes Res Clin Prac. 2005;67(2):152–62.

Lear SA, Ignaszewski A, Linden W, Brozic A, Kiess M, Spinelli JJ, Haydn Pritchard P, Frohlich JJ. The extensive lifestyle management intervention (ELMI) following cardiac rehabilitation trial. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(21):1920–7.

Miura S, Yamaguchi Y, Urata H, Himeshima Y, Otsuka N, Tomita S, Yamatsu K, Nishida S, Saku K. Efficacy of a multicomponent program (patient-centered assessment and counseling for exercise plus nutrition [PACE+ Japan]) for lifestyle modification in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2004;27(11):859–64.

O'Brien KM, Wiggers J, Williams A, Campbell E, Hodder RK, Wolfenden L, Yoong SL, Robson EK, Haskins R, Kamper SJ, et al. Telephone-based weight loss support for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018;26(4):485–94.

Oldroyd JC, Unwin NC, White M, Mathers JC, Alberti KG. Randomised controlled trial evaluating lifestyle interventions in people with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;72(2):117–27.

Rimmer JH, Rauworth A, Wang E, Heckerling PS, Gerber BS. A randomized controlled trial to increase physical activity and reduce obesity in a predominantly African American group of women with mobility disabilities and severe obesity. Prev Med. 2009;48(5):473–9.

Sone H, Iimuro S, Tanaka S, Oida K, Yamasaki Y, Oikawa S, Ishibashi S, Katayama S, Yamashita H, Ito H, et al. Long-term lifestyle intervention lowers the incidence of stroke in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide multicentre randomised controlled trial (the Japan diabetes complications study). Diabetologia. 2010;53(3):419–28.

Wattanakorn K, Deenan A, Puapan S, Kraenzle SJ. Effects of an eating behaviour modification program on Thai people with diabetes and obesity: a randomised clinical trial. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2013;17(4):356–70.

Williams A, Wiggers J, O'Brien KM, Wolfenden L, Yoong SL, Hodder RK, Lee H, Robson EK, McAuley JH, Haskins R, et al. Effectiveness of a healthy lifestyle intervention for chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2018;159(6):1137–46.

Altenburg WA, ten Hacken NH, Bossenbroek L, Kerstjens HA, de Greef MH, Wempe JB. Short-and long-term effects of a physical activity counselling programme in COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):112–21.

Dogru A, Ovayolu N, Ovayolu O. The effect of motivational interview persons with diabetes on self-management and metabolic variables. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69(3):294–300.

Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, Luecking C, Kirbach K, Kelly SC, De Las FL, He S, Okunade AL, Patterson BW, Klein S. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab. 2016;23(4):591–601.

Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, Knox SA. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aust. 2008;189(2):72–7.

Dean E, Söderlund AJ. What is the role of lifestyle behaviour change associated with non-communicable disease risk in managing musculoskeletal health conditions with special reference to chronic pain? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16(1):87.

Conn VS, Valentine JC, Cooper HM. Interventions to increase physical activity among aging adults: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(3):190–200.

Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Brown SA, Brown LM. Meta-analysis of patient education interventions to increase physical activity among chronically ill adults. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(2):157–72.

Howlett N, Trivedi D, Troop NA, Chater AM. Are physical activity interventions for healthy inactive adults effective in promoting behavior change and maintenance, and which behavior change techniques are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(1):147–57.

Murray JM, Brennan SF, French DP, Patterson CC, Kee F, Hunter RF. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions in achieving behaviour change maintenance in young and middle aged adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;192:125–33.

Samdal GB, Eide GE, Barth T, Williams G, Meland E. Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults; systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Int J Behav Nutr Phy Act. 2017;14(1):42.

Conn VS, Minor MA, Burks KJ, Rantz MJ, Pomeroy SH. Integrative review of physical activity intervention research with aging adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(8):1159–68.

Sansano-Nadal O, Giné-Garriga M, Brach JS, Wert DM, Jerez-Roig J, Guerra-Balic M, Oviedo G, Fortuño J, Gómara-Toldrà N, Soto-Bagaria L, Pérez LM. Exercise-based interventions to enhance long-term sustainability of physical activity in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2019;16(14):2527.

Hruby A, Hu FB. The epidemiology of obesity: a big picture. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015 Jul 1;33(7):673–89.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corra U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, Graham I. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315–81.

Claas SA, Arnett DK. The role of healthy lifestyle in the primordial prevention of cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Reps. 2016;18(6):56.

Mudaliar U, Zabetian A, Goodman M, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Albright AL, Gregg EW, Ali MK. Cardiometabolic risk factor changes observed in diabetes prevention programs in US settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(7):e1002095.

Dunkley AJ, Bodicoat DH, Greaves CJ, Russell C, Yates T, Davies MJ, Khunti K. Diabetes prevention in the real world: effectiveness of pragmatic lifestyle interventions for the prevention of type 2 diabetes and of the impact of adherence to guideline recommendations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):922–33.

Williamson DF. Weight change in middle-aged Americans. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):81–2.

De Koning L, Merchant AT, Pogue J, Anand SS. Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular events: meta-regression analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(7):850–6.

Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):88.

Epiphaniou E, Ogden J. Evaluating the role of life events and sustaining conditions in weight loss maintenance. J Obes. 2010;2010:859413. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/859413.

World Health Orginisation. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour: at a glance. 2020.

Leijon ME, Stark-Ekman D, Nilsen P, Ekberg K, Walter L, Ståhle A, Bendtsen P. Is there a demand for physical activity interventions provided by the health care sector? Findings from a population survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):34.

Börjesson M. Promotion of physical activity in the hospital setting. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2013;64:162–5.

Johnson A, Baum F. Health promoting hospitals: a typology of different organizational approaches to health promotion. Health Promot Int. 2001;16(3):281–7.

Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: twenty-five years of empirical studies. Res Soc Work Pract. 2010;20(2):137–60.

Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36(5):427–40.

Randall DM, Fernandes MF. The social desirability response bias in ethics research. J Bus Ethics. 1991;10(11):805–17.

Corder K, Brage S, Ekelund U. Accelerometers and pedometers: methodology and clinical application. Curr Opin Clin Nutr. 2007;10(5):597–603.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Angela Mundy and Mrs. Angela Johns-Hayden for their help in building the final search database. We acknowledge the support of the Bendigo Tertiary Education Anniversary Foundation and Holsworth Research Initiative for Professor Kingsley’s research.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB1, SB3 and MK conceived the study idea and design. SB1, JL, SB3 PO’H and MK screened the articles. SB1 and OH extracted the data and performed the risk of bias and quality assessments. SB1, SB3 and MK conducted the data analysis. SB1 wrote the draft manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Barrett, S., Begg, S., O’Halloran, P. et al. The effect of behaviour change interventions on changes in physical activity and anthropometrics in ambulatory hospital settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 18, 7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01076-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01076-6