Abstract

Background

Progress in mobile health (mHealth) technology has enabled the design of just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs). We define JITAIs as having three features: behavioural support that directly corresponds to a need in real-time; content or timing of support is adapted or tailored according to input collected by the system since support was initiated; support is system-triggered. We conducted a systematic review of JITAIs for physical activity to identify their features, feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness.

Methods

We searched Scopus, Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, DBLP, ACM Digital Library, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov and the ISRCTN register using terms related to physical activity, mHealth interventions and JITAIs. We included primary studies of any design reporting data about JITAIs, irrespective of population, age and setting. Outcomes included physical activity, engagement, uptake, feasibility and acceptability. Paper screening and data extraction were independently validated. Synthesis was narrative. We used the mHealth Evidence Reporting and Assessment checklist to assess quality of intervention descriptions.

Results

We screened 2200 titles, 840 abstracts, 169 full-text papers, and included 19 papers reporting 14 unique JITAIs, including six randomised studies. Five JITAIs targeted both physical activity and sedentary behaviour, five sedentary behaviour only, and four physical activity only. JITAIs prompted breaks following sedentary periods and/or suggested physical activities during opportunistic moments, typically over three to four weeks. Feasibility challenges related to the technology, sensor reliability and timeliness of just-in-time messages. Overall, participants found JITAIs acceptable. We found mixed evidence for intervention effects on behaviour, but no study was sufficiently powered to detect any effects. Common behaviour change techniques were goal setting (behaviour), prompts/cues, feedback on behaviour and action planning. Five studies reported a theory-base. We found lack of evidence about cost-effectiveness, uptake, reach, impact on health inequalities, and sustained engagement.

Conclusions

Research into JITAIs to increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour is in its early stages. Consistent use and a shared definition of the term ‘JITAI’ will aid evidence synthesis. We recommend robust evaluation of theory and evidence-based JITAIs in representative populations. Decision makers and health professionals need to be cautious in signposting patients to JITAIs until such evidence is available, although they are unlikely to cause health-related harm.

Reference

PROSPERO 2017 CRD42017070849.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mobile health (mHealth) interventions have great potential to improve access to and use of behaviour change support, in addition to or instead of support delivered face-to-face, by phone, print or websites. mHealth is defined as medical and public health practice supported by mobile devices, such as mobile phones, patient monitoring devices, personal digital assistants (PDAs), and other wireless devices [1]. mHealth is especially promising for changing physical activity, defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that require energy expenditure” [2], and sedentary behaviour. Three meta-analyses have compared mHealth interventions aimed at promoting physical activity with usual care and support their potential for effectiveness. A meta-analysis of 21 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) found that mHealth interventions achieved a significant decrease in sedentary behaviour and a non-significant increase in total physical activity, moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity and walking compared to usual care [3]. A second meta-analysis included 15 RCTs evaluating computer, mobile and wearable technology tools to reduce sedentary behaviour. These interventions significantly reduced sitting time up to 6 months after the intervention, but only in studies with shorter follow-ups [4]. A third meta-analysis of eight RCTs of mobile phone, self-monitoring and website interventions aimed at increasing physical activity found that effects on physical activity were similar to face-to-face interventions or written materials without technology [5].

The use of mHealth technology has been recommended as portable devices make intervention delivery more interactive and responsive [3, 6, 7], for instance, by sending feedback messages in real time based on the user’s location. Progress in mHealth technology has enabled the design of interventions which aim to deliver behaviour change support in real time that is matched to when users most want or need the support. Multiple terms have been used for such interventions: just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs), context-aware interventions, ecological momentary interventions (EMI) and real-time interventions. In this paper, we use the term JITAI. JITAIs have the potential to address situations when people are likely to engage in an unhealthy behaviour, for example at specific locations like a bar where people may experience an urge to smoke. They may also facilitate opportunities to perform healthy behaviours such as walking instead of taking the bus whilst commuting to work [8].

Nahum-Shani et al. [8] describe JITAIs as being designed to dynamically address the need of the user via the provision of the right amount or type of support needed at the right time. Examples described include interventions that prompt users to complete an assessment at specific times during the day, immediately followed by provision of behavioural support, such as self-management strategies if the user reports difficulties. Naughton [9] provides a definition of JITAIs as a hybrid of user-triggered and server-triggered support. Typical systems use sensors on, or connected to, the user’s smartphone (apps or other sources of data input such as online shopping habits). These are employed in real-time to interpret the context of the user’s environment and/or current mood and emotions, and deliver behaviour change support when it is appropriate, triggered by the system and not the user.

We adopt the Naughton [9] definition and define behavioural JITAIs as having three key features: 1) The intervention aims to provide behavioural support that directly corresponds to a need in real time when the user is at risk of engaging in a negative health behaviour or has an opportunity to engage in a positive behaviour in line with their health goal(s); 2) the content or timing of behavioural support is adapted or tailored according to input (data) collected by the system since the support was initiated, also referred to as ‘dynamic tailoring’ [10] (e.g. an app which includes the use of location sensors such as a Global Positioning System [GPS] and senses that the user is near a green space where they can be active and their digital diary shows they are not busy); and 3) behavioural support is triggered by the system and not directly by users themselves (e.g. an unsolicited mobile app notification is sent in specific situations, for instance when the in-built accelerometer has sensed a prolonged period of sitting, as opposed to users opening the app). JITAIs differ from ‘just-in-time’ interventions and tailored support because ‘just-in-time’ interventions include features 1 and 2 but not 3; or features 1 and 3 but not 2. Likewise, tailored support interventions include features 2 and 3, but not 1.

JITAIs have targeted, among others, eating disorders, mental illness, obesity and weight management, physical activity [8] and smoking cessation [9], and are receiving increasing attention in the mHealth literature. JITAIs for physical activity are promising as they offer a different type of support to most existing interventions by their potential to intervene in response to changing contexts. Physical activity is strongly influenced by context such as the built environment [11], which could be exploited by JITAIs. There is a need to synthesise what is known about JITAIs for physical activity to inform whether policy makers and healthcare providers should promote JITAIs for use in health and social care settings, and to identify evidence gaps to be addressed by research. We identified two papers about the conceptualisation of JITAIs. Nahum-Shani et al. [8] report two examples of JITAIs aimed at promoting physical activity or reducing sedentary behaviour, and Muller et al. [12] identified three JITAIs aimed at increasing physical activity or reducing sedentary behaviour in older adults. However, neither conducted a systematic search for JITAIs and synthesised the evidence about the JITAIs around their effectiveness, feasibility or acceptability. A recent systematic review focused on just-in-time feedback in diet and physical activity interventions, rather than JITAIs [13]. We are not aware of any systematic reviews of JITAIs which specifically target physical activity.

The primary question for our systematic review was: (1) What are the features, feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of JITAIs to promote physical activity? Secondary questions were: (2) Which delivery platforms have been used?; (3) Which groups or populations have been targeted?; (4) What are the active ingredients (behaviour change techniques) and theory base of JITAIs?; (5) What is the uptake and reach of JITAIs, including any impact on health inequalities?; (6) What is the level of initial and sustained engagement with JITAIs, and how have people used them?; (7) Which research designs have been used to develop and evaluate JITAIs, and (8) Has any health economic evaluation or modelling been conducted?

Methods

Design

This systematic review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist. The protocol is published on PROSPERO (CRD42017070849) [14].

Inclusion criteria

We included studies of any design, including qualitative and quantitative studies reporting data or findings from development work, feasibility or pilot studies and definitive evaluation studies. We excluded conceptual papers that did not report any data such as papers about the theory base of JITAIs or purely methodological papers. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of mHealth interventions were excluded, but they were checked for any eligible papers about JITAIs. We included studies which aimed to promote physical activity (by increasing activity or reducing sedentary behaviour) in any setting and targeted participants of any age. Studies were included when they reported a JITAI which included the three features defined in the introduction and were excluded if they were simply ‘just-in-time’ or ‘tailored support’ interventions. Given the diverse terminology used for JITAIs, we did not rely on the use of this term during screening and decided on eligibility based on the intervention description. We included JITAIs which targeted multiple behaviours provided that a substantial part of the intervention targeted physical activity and we could extract data about the physical activity component. To be included, studies had to investigate or report one or more of the following measures: physical activity, engagement, uptake, reach, retention, feasibility and acceptability. Hence, we included studies that did not directly seek to promote physical activity among their participants providing they investigated these variables using a JITAI.

Search strategy

We searched Scopus, Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, DBLP, ACM Digital Library, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the ISRCTN register. Initial searches were conducted during May–June 2017 and updated searches in November 2018. They were adapted for each database and no language or date restrictions were employed. We combined search terms related to physical activity, mHealth interventions and JITAI features (Additional file 1).

Paper screening and data extraction

All papers identified through the searches were downloaded into EndNote and duplicates removed. Screening was undertaken in EndNote in three phases. In the initial search, titles of all papers were doubly screened (JH and KL) and papers which obviously failed to meet inclusion criteria were excluded. WH resolved any discrepancies. Abstracts were screened (JH and WH) and reasons for exclusion recorded. Full texts of all remaining papers were screened for inclusion (JH, KL and WH). In the updated search, JH conducted title screening, JH and WH abstract screening, and WH full-text screening. Inter-rater agreement during the initial search was calculated by the number of papers on which two reviewers agreed (either inclusion or exclusion), divided by the total number of double-screened papers. Following the PRISMA statement [15], we recorded reasons for exclusion at the full-text screening phase.

Data extraction and synthesis

The first author extracted data from all included papers. This was independently validated by four reviewers (FN, AJ, KL and JH) and FN independently validated the extraction of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) [16]. We extracted general information about the included papers, features of the JITAI, data about the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of JITAIs, delivery platforms, target groups/populations and user engagement. Data extracted about JITAI features included types of triggers (data that cause the system to respond); data used for the triggers and their source (e.g., location, GPS); technology platform; key intervention features; behaviour change techniques and theory base. Data extracted about intervention delivery included context or setting of delivery; other intervention components delivered alongside the JITAI; and any implementation issues and challenges. Finally, we extracted data about the following outcomes: feasibility, acceptability, engagement [17], effectiveness and health-economic outcomes. Given the wide range of study designs included, data synthesis was narrative.

Assessment of study reporting

Given the diversity of study designs and the absence of an agreed tool to assess methodological quality of JITAIs, we did not formally assess risk of bias but provide a narrative summary of the key risks of bias, such as study designs used, uptake and reach. We used the mHealth evidence reporting and assessment checklist (mERA), which includes criteria for reporting what an mHealth intervention is (content), where it is being implemented (context), and how it was implemented (technical features) [18]. Each item was scored as ‘fully reported’, ‘partially reported’ (only some evidence reported) or ‘not reported’, rather than ‘yes’ or ‘no’ as many papers only provided partial evidence on the items.

Results

Study selection

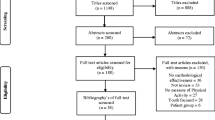

In total we screened 2200 titles (Fig. 1) and checked 365/1416 titles (initial search). During abstract screening we excluded 675 out of 840 papers; key reasons were that papers were conceptual, interventions were not JITAIs or did not target physical activity. Inter-rater agreement (initial search) during double screening of 20% of abstracts (n = 126) was 91% (115/126). We screened 169 full-text papers: 165 from abstract screening, plus four papers following discussion of discrepancies after abstract screening [1], a search of the ISRCTN database [1] and an additional search for RCTs classified as ‘completed’ in ClinicalTrials.gov [2]. We identified three companion papers [19,20,21], one through paper screening and two through reading included papers and extracted any additional data. Inter-rater agreement during double screening of 20% of full-text papers (n = 26/132; initial search) was high: 100% for AJ and KL and 92% for JH and WH. The key reason for exclusion at the full-text phase was that the intervention did not include any JITAI feature, or only one. For instance, some interventions only provided real-time feedback on physical activity using text or graphics (e.g., a garden with flowers) [22, 23] or rewarded previous activity [24], and so were not directly targeting a real time opportunity to be active.

We included 19 papers referring to 14 unique JITAIs evaluated in 14 studies (referred to as ‘studies’ below). Two of the 14 JITAIs [25, 26] were optimised versions, informed by evaluations of earlier versions [27, 28].

Study and participant characteristics

Eight studies were conducted in the US, five in The Netherlands and one in Portugal (Table 1). All except one [29] were described as feasibility or pilot studies; six studies [28,29,30,31,32,33] were randomised (including Van Dantzig 2013, study 2), two quasi-experimental [20, 34] and six studies reported data on feasibility, acceptability etc., but not intervention effects on behaviour (including Van Dantzig 2013, study 1) [26, 27, 33, 35,36,37]. Thirteen studies were conducted in the community, including three in universities [25, 31, 36], two in the workplace [29, 33] and one study in secondary care [20]. Sample sizes ranged from 6 [27] to 256 [35]; the latter study was an outlier as participants were recruited online (the next largest sample size was 86 [33]). Ten studies recruited convenience samples such as students and colleagues; these studies typically did not report any inclusion criteria. Two studies recruited at-risk groups (overweight) [30, 32] and a further two studies recruited individuals with COPD [20] and type 2 diabetes [34]. Participants were typically adults aged between 20 and 60 years of mixed gender. Most studies failed to report other participant characteristics; four studies reported education level (which tended to be high) and seven employment status.

JITAI features, delivery and content

We discuss a few examples illustrating the distinct features of JITAIs (see Table 2 and Additional file 2: Table S1 for details). Intervention duration ranged from 1 h [37] to 3 months [20, 35], and was typically 3 to 4 weeks. Five JITAIs targeted sedentary behaviour only [30, 32,33,34, 37], four physical activity only [20, 26, 27, 29], and five both sedentary behaviour and physical activity [25, 28, 31, 35, 36]. Two JITAIs also targeted calorie intake [25, 28], two provided feedback on number of calories burned [32, 36], and in one JITAI participants could set goals for keeping healthy, losing weight and burning calories [36]. Other intervention components included a face-to-face meeting to explain the use of the smartphone (in some studies participants were given a smartphone) and/or the app, to give participants devices, and explain the rationale for behaviour change (used in six studies [26, 30, 31, 34, 36]), and access to a dedicated or commercial website for physical activity feedback and instructions (used in five studies [20, 25, 28, 32, 33]).

Real-time support was triggered when the in-built accelerometer sensed no activity for a specified time and a prompt was sent to take a break from sitting in ten JITAIs [25, 28, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. In nine JITAIs [20, 25,26,27,28,29, 31, 35, 36], real-time support was triggered and activities suggested when opportunistic moments for walking or other activities were sensed. These nine JITAIs used multiple sensors, mostly in-built accelerometers and GPS, but also sensors or apps which used time of day, weather and digital diaries to identify opportunistic moments for engaging in physical activity or continuing current activity. All used apps on Android, with the exception of one study which used IOS and software installed on participants’ computers [33], and a second study which used a health watch [29]. Five studies [20, 29, 31,32,33] used physical activity wearables, smartwatches or activity sensors (wireless activity sensor or computer software measuring keyboard and mouse activity).

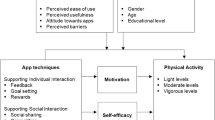

Five JITAIs were based on theory [25, 28, 31, 33, 37], most commonly Fogg’s Behaviour Model [38]. Two further studies [20, 35] mentioned a theory, but did not report explicitly how theory informed the JITAI.

We coded 19 BCTs targeting physical activity in the JITAIs (Table 3). Four BCTs were included in the majority of JITAIs: goal setting (behaviour) and prompts/cues (14/14 JITAIs); feedback on behaviour (11/14) and action planning (9/14). Goals and action plans were usually provided by the system rather than prompting users to define their own. Less frequent BCTs included discrepancy between current behaviour and goal (4/13); information about antecedents, social comparison and graded tasks (3/13). The remaining BCTs were included in one or two JITAIs only.

Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

Five out of six randomised studies measured physical activity objectively, with two using independent accelerometers (Table 4). All studies collected data during intervention delivery only. Four studies reported retention rates, which ranged from 85% [30] to 100% [28]. Participants were randomised to an intervention or control group in four studies [28, 29, 31, 33], one study used a randomised crossover design [32], and another randomised each participant to three intervention conditions in succession [30]. Two studies found evidence of a positive effect. In Bond et al. [30] and Thomas et al. [47], the percentage time spent in sedentary behaviour (primary outcome) decreased significantly in all three intervention conditions, compared to baseline (p < .005). The intervention condition in which participants were prompted to take 3-min physical activity breaks resulted in greater decreases than the condition prompting 12-min breaks (p = 0.04). Finkelstein et al. [32] found that the number of episodes of prolonged inactivity (> 2 h) per day was lower (p < .02) when participants received inactivity reminders, compared to control when they did not receive reminders. Van Dantzig et al. [33] reported mixed findings: messages which prompted participants to reduce sitting reduced their use of the computer over six weeks, compared to the control group who received nothing, but they did not increase objectively measured physical activity. Finally, three studies found no statistically significant effects on physical activity. Ding et al. [31] showed no evidence of effects on step counts over 3 weeks of an intervention which reminded participants to walk (more) when opportunistic moments were sensed, compared to a control group who received random reminders without contextual information. Rabbi et al. [28] found a non-significant trend (p = .055) in self-reported walking of an intervention which provided specific suggestions based on location and activity levels: intervention participants reported an increase in walking of 10 min per day over 3 weeks, whilst no change was observed in the control group who received a digital intervention with general recommendations. Van Dantzig et al. [33] found no evidence of effects on daily step count of an intervention which sent real-time support in specific contexts, compared to messages sent at fixed times.

Four non-randomised studies reported physical activity data. Two used independent accelerometers and reported retention rates of 60% at 3 months [20] and 89% at one-month follow-up [34]. They found mixed evidence for an intervention effect. In Tabak [20], 5/10 participants increased objectively measured physical activity between baseline and three-month follow-up, but no participant had maintained increases at 3 months. Pellegrini et al. [34] found a trend for an objective decrease in sedentary time (p = .08), and significant increase in light physical activity (p = .047) between baseline and 1 month. Two interventions resulted in self-reported increases in physical activity within participants. Rabbi et al. [25] found increases in minutes of walking per day (p < .005) over the final three intervention weeks compared to control. In one study [26], 86% of participants reported at the end of the intervention that they had become a little or much more active. The remaining four studies reported no data on intervention effects on physical activity or sedentary behaviour as they focused on feasibility and acceptability [27, 35,36,37].

No study reported data on resource use or cost-effectiveness.

Uptake, reach, retention, engagement, feasibility and acceptability

Only one study reported the uptake or reach of JITAIs [31]: two out of 19 participants failed to start the app due to incompatibility with their phones (Table 4). Reasons for loss to study follow-up included battery problems, loss of interest, personal and medical reasons.

A wide range of engagement measures were used in nine studies which reported data (Additional file 3: Table S2). They included number of days or weeks that users carried smartphones [30] or used the app [26, 35], adherence to and evaluative responses of real-time messages [20, 27, 28, 30, 31], and frequency, duration and nature (‘glance’, ‘engage’ and ‘review’) of usage sessions [35]. No study reported that participant engagement was a challenge, but intervention duration was generally short. One study [35] reported that all 256 participants recruited online had quit the app by ten months.

Feasibility measures varied widely. Technological challenges included short battery life of the smartphone [33, 34, 36], the GPS requiring substantial battery power [26], technology only working when smartphone and intervention accelerometers had wireless connection [34], and participants not carrying smartphones when at work and exercising [37]. Other challenges included sensing and delivery of just-in-time messages: the digital diary was unreliable during weekends as participants did not update it [27], 43% of just-in-time messages were received too early (17%) or too late (26%) (users were asked after each notification whether it was just-in-time, too early or too late) [27]. In qualitative interviews some participants found physical activity suggestions hard to follow and not reflecting their activity preferences [28].

In terms of acceptability, participants liked short-term graded goals and explanations of why reminders to walk (more) were triggered [31], activities which could be easily integrated in daily life [26, 27], and they reported high acceptance and willingness to keep using the JITAI [32]. In qualitative interviews, just-in time messages were perceived to be more timely than random messages and resulted in less complaints compared to the control group who received non-context aware, random messages. Intervention participants reported becoming more aware of opportunities to walk, whereas this was not the case for control participants [31]. Rabbi et al. [28] reported that the number of physical activity and dietary suggestions participants wanted to follow (βi = 2.9, p < 0.001) and relatedness of suggestions to life (βi = 0.5, p < 0.001) was higher for just-in-time messages compared to randomly selected messages. JITAI participants followed suggestions more than control participants even when there were barriers (p < 0.001, d = 0.44) or when they experienced negative emotions (p < 0.001, d = 0.55). In qualitative interviews, some participants reported that suggestions were actionable and relevant to their lives; participants who considered increasing their activity were eager to follow them and the messages reinforced maintenance [28]. In another study [29] intervention participants liked real-time suggestions to build activity into their daily routines, but some did not want to be disturbed during daily activities and preferred activity during dedicated times. Features that participants did not like included being told too frequently that they were inactive [36] and participants sharing their activity data with others on social media [33], though in one study participants could not share their data on social media but reported that this would be highly motivating [37].

Quality of intervention descriptions

At least eight out of 13 studies (the two Lin et al. interventions were treated as one as the descriptions were identical) reported full details on intervention delivery (mERA item #4), intervention content (#5), formative research and user testing (#6) and user feedback (#7) (Table 5). In contrast, at least nine out of 12 studies did not report any details on integration into existing health information systems (#3), cost-assessment (#9), user information and training (#10), solutions for delivery at scale (#11), adaptation of the intervention (#12), data security/confidentiality protocols (#14) and alignment with national and regulatory guidelines (#15).

Discussion

We identified a heterogeneous set of 19 papers evaluating 14 unique JITAIs, mostly among convenience samples of young and middle-age adults. The JITAIs prompted breaks following sedentary periods and/or suggested physical activities during opportunistic moments. Five out of 14 JITAIs reported a theory base. Common behaviour change techniques were goal setting (behaviour), prompts/cues, action planning and feedback on behaviour. Intervention duration was typically three to four weeks. We found mixed evidence for intervention effects on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. However, no study was designed to be powered to detect effects on behaviour and only six studies were randomised. Feasibility challenges related to the technology, reliability of sensors and timeliness of just-in-time messages. There was a lack of evidence about cost-effectiveness, uptake, reach, impact on health inequalities, sustained engagement, and integration in existing systems.

Crucial evidence to inform the adoption of JITAIs in health and care systems is their added value compared to mHealth interventions without just-in-time messages (e.g., scheduled, fixed or random). Two studies supported the assumption that JITAIs deliver support when users are most likely to be receptive. Rabbi et al. found that, compared to randomly selected messages, participants intended to follow the just-in-time messages more, found them more relevant to their life, and followed them more when they experienced barriers or negative emotions [28]. In Ding et al., participants found just-in-time messages more timely than random messages, they increased their awareness of opportunities to walk, and resulted in less complaints [31]. However, this potential is only fully realised if messages are indeed just-in-time. The one study which assessed this found that 43% of messages were reported not to be just-in-time [27].

Paper screening was challenging due to a lack of shared terminology about what constitutes a JITAI and lack of clarity in descriptions of JITAI features. We used a published definition which distinguishes JITAIs from interventions which provide feedback on physical activity in real time, either numerical or through visual displays, without explicit prompts to further increase activity. We cannot assume that these interventions include ‘incentives’ or ‘rewards’ as the BCT Taxonomy v1 [16] specifies that these need to be valued by the users. A randomised controlled trial showed that provision of personalised feedback on physical activity alone does not change behaviour [39]. Our definition specifies that behaviour change support in real time needs to include additional BCTs (e.g., prompts/cues, goal setting and action planning) beyond feedback or reinforcement of previous activity to encourage further increases in activity. On this basis, we excluded some studies [22, 23, 40] which others described as JITAIs. It was also challenging to draw the line due to poorly described interventions. We urge mHealth researchers to report their intervention features clearly, whether they are JITAI or non-JITAI, and to achieve consensus about what constitutes a JITAI.

Our review advances the evidence base about JITAIs for physical activity. We chose to consider both physical activity and sedentary behaviour as they are closely aligned, recognising that others consider them as distinct behaviours. We identified 18 studies of which only three [30, 33, 36] were included in a previous review [41] which focused on design features and one [30] in a systematic review of just-in-time feedback [13]. None of our studies was included in recent meta-analyses of mHealth interventions, possibly because most studies were not RCTs and any RCTs were published recently [3,4,5]. Prior to this systematic review there was uncertainty about the feasibility, acceptability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of JITAIs for physical activity. Our review has provided initial insights on feasibility challenges, illuminated that users found JITAIs acceptable, and found mixed evidence in terms of effectiveness and lack of evidence about cost-effectiveness. However, many evidence gaps remain and our systematic review corroborates earlier reports that research into JITAIs for physical activity is in its early stages [12]. Many JITAIs appeared to be designed without behavioural science input, as they lacked a theory and evidence-base to underpin content.

We identified major evidence gaps, informing an ambitious research agenda in terms of target groups, study design and JITAI development work. In terms of target group, JITAIs need to be evaluated among representative real-world and clinical populations, including uptake, reach and impact on health inequalities, to inform decisions whether to adopt them in health and social care settings. To reach all smartphone users, JITAIs need designing for both IOS and Android smartphones and be potentially incorporated into smartwatches and other wearables.

In terms of study design, studies need to assess the additional value of just-in-time support by comparing JITAIs to interventions providing not just-in-time support, and assess whether messages were just-in-time, relevant to context, setting and motivational state, assess participants’ receptiveness to the messages and their intention to act on the messages, whether they followed any suggestions, and intervention engagement over time. Studies need to include independent objective measurement of physical activity and sedentary behaviour and follow-up beyond the end of the intervention. There is also a need for mixed methods process evaluation with a broad range of measures: engagement, fidelity, how participants use JITAIs, measures along the hypothesised mechanism of intervention effect and contextual factors. This would illuminate how, when, and for whom JITAIs work and inform adaptation and integration of JITAIs into health and care settings, a key evidence gap in the wider mHealth literature about physical activity [42].

We recommend that developers of JITAIs use appropriate theory and evidence-based BCTs [16], use design principles for JITAIs [43] and design a logic model. For instance, socio-ecological theory includes broader determinants of individual behaviour (social and physical environment) which could inform just-in-time support. The JITAIs included a small number of BCTs and lacked evidence-based BCTs targeting motivation and maintenance such as problem-solving, reviewing behavioural goals, social support, information about behavioural consequences and habit formation. Developers could consider a wider range of messages beyond prompting breaks in sitting and suggesting activities alone to encourage and maintain behaviour change and sustain engagement over time. All JITAIs used behavioural data (physical activity levels, sedentary behaviour time) or location data to trigger just-in-time support. None used data about psychological and affective states (motivation, mood, stress levels) which can influence physical activity and sedentary behaviour, perhaps due to the challenges of sensing these states. We recommend that research into JITAIs addresses these challenges and incorporates this evidence into the development of JITAIs which use data about psychological and affective states to trigger support. We recommend that authors use the mERA checklist to improve intervention descriptions, report BCTs included and which intervention features are JITAI and non-JITAI. JITAIs need to be developed in co-production with users and could employ innovative methodologies such as MOST [44] and SMART [45] to optimise JITAIs prior to definitive evaluation.

We recommend that decision makers adopt JITAIs for physical activity promotion when research evidence shows that they increase physical activity or reduce sedentary behaviour, and if such evidence is unavailable, that they incorporate evaluation. Although JITAIs are unlikely to cause harm if walking and sitting less is their main aim, we need evidence about their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Health and care professionals can signpost or refer people to evidence-based mHealth support for physical activity, including JITAIs. Industry should work with developers to optimise battery life and the delivery of just-in-time support.

The strengths of our systematic review include a comprehensive search of ten databases, a clear definition of JITAIs to guide paper screening, the identification of studies that had not been previously synthesised, and in-depth synthesis focusing on study design, intervention content and delivery, and a broad range of outcome and process measures. Our review also had limitations. The absence of an agreed definition of a JITAI made the search for papers and screening challenging, compounded by lack of clear reporting of JITAI features and diversity in reporting across disciplines (computer science, engineering, behavioural science). Consequently, we may not have identified all eligible papers, although inter-rater agreement during full-text screening was high. In addition, it was challenging to judge the quality of intervention descriptions, using the mERA checklist. Finally, we considered physical activity as any movement requiring energy expenditure, and therefore sedentary time as any time not spent in physical activity, whilst others regard physical activity and sedentary behaviour as distinct. This is an ongoing topic of research and debate [46]. We acknowledge the distinction, as well as that changing these two broad categories of behaviour may require different intervention approaches.

Conclusions

Research into JITAIs to increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour is in its early stages and consistent use and a shared definition of the term ‘JITAI’ will aid evidence synthesis. We need robust outcome and process evaluations of theory and evidence-based JITAIs in representative populations and examination of their integration in health and care systems. Decision makers and health and care professionals need to be cautious in signposting patients to JITAIs until such evidence is available, although JITAIs which target walking and sedentary behaviours are unlikely to cause health-related harm.

Abbreviations

- BCT:

-

Behaviour change technique

- EMI:

-

Ecological momentary interventions

- GPS:

-

Global Positioning System

- JITAI:

-

Just-in-time adaptive intervention

- mERA:

-

mHealth evidence reporting and assessment

- mHealth:

-

Mobile health

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

References

World Health Organization. mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies: second global survey on eHealth. http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_mhealth_web.pdf (Accessed 19 Dec 2018). 2011.

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126–31.

Direito A, Carraca E, Rawstorn J, Whittaker R, Maddison R. mHealth technologies to influence physical activity and sedentary behaviors: behavior change techniques, systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(2):226–39.

Stephenson A, McDonough SM, Murphy MH, Nugent CD, Mair JL. Using computer, mobile and wearable technology enhanced interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):105.

Hakala S, Rintala A, Immonen J, Karvanen J, Heinonen A, Sjogren T. Effectiveness of technology-based distance interventions promoting physical activity: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49(2):97–105.

Muller AM, Alley S, Schoeppe S, Vandelanotte C. The effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):109.

Middelweerd A, Mollee JS, van der Wal CN, Brug J, Te Velde SJ. Apps to promote physical activity among adults: a review and content analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:97.

Nahum-Shani S, Smith S, Tewari A, Witkiewitz K, Collins LM, Spring B, et al. Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs): An organizing framework for ongoing health behavior support. (Technical Report No. 14–126). University Park, PA: The Methodology Center, Penn State; 2014.

Naughton F. Delivering “Just-in-time” smoking cessation support via mobile phones: current knowledge and future directions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;19(3):379–83.

Krebs P, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS. A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Prev Med. 2010;51(3–4):214–21.

Karmeniemi M, Lankila T, Ikaheimo T, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Korpelainen R. The built environment as a determinant of physical activity: a systematic review of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(3):239–51.

Müller AM, Blandford A, Yardley L. The conceptualization of a just-in-time adaptive intervention (JITAI) for the reduction of sedentary behavior in older adults. mHealth. 2017;3(37). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5682389/

Schembre SM, Liao Y, Robertson MC, Dunton GF, Kerr J, Haffey ME, et al. Just-in-time feedback in diet and physical activity interventions: systematic review and practical design framework. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(3):e106.

Hardeman W, Houghton J, Lane K, Jones A, Naughton F. A systematic review of just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) to promote physical activity. CRD42017070849 Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017070849: 2017.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br Med J. 2009;339:b2535.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis JJ, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Perski O, Blandford A, West R, Michie S. Conceptualising engagement with digital behaviour change interventions: a systematic review using principles from critical interpretive synthesis. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(2):254–67.

Agarwal S, LeFevre AE, Lee J, L'Engle K, Mehl G, Sinha C, et al. Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist. Br Med J. 2016;352:i1174.

Lin Y. Motivate mobile application design and development. Motivate : a context-aware mobile application for physical activity promotion. Eindhoven: Technische Universiteit Eindhoven; 2013. p. 73–94. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR7501852013. https://pure.tue.nl/ws/files/3727051/750185.pdf

Tabak M. Improving long-term activity behaviour of individual patients with COPD using an ambulant activity coach. Telemedicine for patients with COPD: new treatment approaches to improve daily activity behaviour: Centre for Telematics and Information Technology, University of Twente, The Netherlands; 2014. p. 97–118.

Ding X. Understanding mobile app addiction and promoting physical activities: University of Massachusetts Lowell; 2016.

King AC, Hekler EB, Grieco LA, Winter SJ, Sheats JL, Buman MP, et al. Harnessing different motivational frames via mobile phones to promote daily physical activity and reduce sedentary behavior in aging adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(4).

Consolvo S, McDonald DW, Toscos T, Chen MY, Froehlich J, Harrison B, et al. Activity sensing in the wild: a field trial of UbiFit garden. Burnett M, Costabile MF, Catarci T, DeRuyter B, Tan D, Czerwinski M, et al., editors 2008. p 1797–806

Bickmore TW, Mauer D, Brown T. Context awareness in a handheld exercise agent. Pervasive Mobile Comput. 2009;5(3):226–35.

Rabbi M, Aung MH, Zhang M, Choudhury T. MyBehavior: automatic personalized health feedback from user behaviors and preferences using smartphones. UBICOMP '15, September 7–11, 2015, Osaka, Japan. 2015:707--18.

Lin Y. Evaluation user study of motivate final version. Motivate : a context-aware mobile application for physical activity promotion. Eindhoven: Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://doi.org/IR750185201/IR7501852013. p. 95-126.

Lin Y, Jessurun J, De Vries B, Timmermans H, editors. Motivate: towards context-aware recommendation mobile system for healthy living. Proceeding of 5th international ICST conference on pervasive computing Technologies for Healthcare; 2011.

Rabbi M, Pfammatter A, Zhang M, Spring B, Choudhury T. Automated personalized feedback for physical activity and dietary behavior change with mobile phones: a randomized controlled trial on adults. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(2).

Van Dantzig SB, M; Krans, M; Van der Lans, A.; De Ruyter, B. Enhancing physical activity through context-aware coaching. Proceedings of Pervasive Health conference (Pervasive Health 2018) ACM, New York York, https://doi.org/10.1145/3240925.3240928. 2018.

Bond DS, Thomas JG, Raynor HA, Moon J, Sieling J, Trautvetter J, et al. B-MOBILE - a smartphone-based intervention to reduce sedentary time in overweight/obese individuals: a within-subjects experimental trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100821.

Ding X, Xu J, Wang H, Chen G, Thind H, Zhang Y. WalkMore: Promoting walking with just-in-time context-aware prompts. IEEE Wireless Health. 2016;2016:65–72.

Finkelstein J, McKenzie B, Li X, Wood J, Ouyang P. Mobile app to reduce inactivity in sedentary overweight women. MedInfo 2015: eHealth-enabled Health. 2015:89–92.

Van Dantzig S, Geleijnse G, Halteren AT. Toward a persuasive mobile application to reduce sedentary behavior. Pers Ubiquit Comput. 2013;17(6):1237–46.

Pellegrini CA, Hoffman SA, Daly ER, Murillo M, Iakovlev G, Spring B. Acceptability of smartphone technology to interrupt sedentary time in adults with diabetes. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5(3):307–14.

Gouveia R, Karapanos E, Hassenzahl M. How do we engage with activity trackers?: a longitudinal study of Habito. UBICOMP '15, September 7–11, 2015, Osaka, Japan. 2015:1305--16.

He Q, Agu E. On11: An activity recommendation application to mitigate sedentary lifestyle. WPA’14, June 16 2014, Bretton Woods, NH, USA. 2014:3--8.

Rajanna V, Lara-Garduno R, Behera DJ, Madanagopal K, Goldberg D, Hammond T, editors. Step up life: a context aware health assistant. HealthGIS’14, November 04–07 2014, Dallas/Fort Worth, TX, USA; 2014.

Fogg B, Editor A behavior model for persuasive design. Proceedings of the 4th international conference on persuasive technology; 2009; 4th international conference on persuasive technology; April 26-29, 2009; Claremont, CA: New York, NY: ACM.

Godino JG, Watkinson C, Corder K, Marteau TM, Sutton S, Sharp SJ, et al. Impact of personalised feedback about physical activity on change in objectively measured physical activity (the FAB study): a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75398.

King AC, Hekler EB, Grieco LA, Winter SJ, Sheats JL, Buman MP, et al. Effects of three motivationally targeted mobile device applications on initial physical activity and sedentary behavior change in midlife and older adults: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156370.

Matthews J, Win KT, Oinas-Kukkonen H, Freeman M. Persuasive technology in mobile applications promoting physical activity: a systematic review. J Med Syst. 2016;40(3):72.

Blackman KC, Zoellner J, Berrey LM, Alexander R, Fanning J, Hill JL, et al. Assessing the internal and external validity of mobile health physical activity promotion interventions: a systematic literature review using the RE-AIM framework. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(10):e224.

Nahum-Shani I, Smith SN, Spring BJ, Collins LM, Witkiewitz K, Tewari A, et al. Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52:446.

Collins LM, Kugler KC, Gwadz MV. Optimization of multicomponent behavioral and biobehavioral interventions for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 1):S197–214.

Collins LM, Nahum-Shani I, Almirall D. Optimization of behavioral dynamic treatment regimens based on the sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trial (SMART). Clin Trials. 2014;11(4):426–34.

Van der Ploeg HP, Hillsdon M. Is sedentary behaviour just physical inactivity by another name? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):142.

Thomas JG, Bond DS. Behavioral response to a just-in-time adaptive intervention (JITAI) to reduce sedentary behavior in obese adults: implications for JITAI optimization. Health Psychol. 2015;34:1261–7.

Ouyang P, Stewart KJ, Bedra ME, York S, Valdiviezo C, Finkelstein J. Text messaging to reduce inactivity using real-time step count monitoring in sedentary overweight females. Circ Conf 2015;131(no pagination).

Hermens H, op den Akker H, Tabak M, Wijsman J, Vollenbroek M. Personalized coaching systems to support healthy behavior in people with chronic conditions. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2014;24(6):815–26.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Julie Houghton and Kathleen Lane were supported by Research Capability Funding, administered by the Norfolk and Suffolk Primary and Community Care Research Office on behalf of the Norfolk and Waveney Clinical Commissioning Groups.

The work was undertaken by the Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (MR/K023187/), is gratefully acknowledged. The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, interpretation of data; and writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this systematic review are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the initiation, conceptualisation and design of this systematic review. WH led all phases of the systematic review, screened papers for inclusion, independently validated paper screening, extracted all data and BCTs, did the methodological assessment, synthesised the findings, and drafted the manuscript. JH designed the literature searches, conducted all the searches, screened papers for inclusion, independently validated paper screening and data extraction, contributed to the interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. KL screened papers for inclusion, independently validated paper screening and data extraction, contributed to the interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. AJ independently validated paper screening and data extraction, contributed to the interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. FN independently validated paper screening, data extraction and BCT extraction, contributed to the interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search terms used for physical activity, mHealth interventions and JITAIs. (DOCX 32 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Description of intervention and control conditions. (DOCX 44 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S2. Engagement with, and feasibility and acceptability of the just-in-time adaptive interventions. (DOCX 43 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hardeman, W., Houghton, J., Lane, K. et al. A systematic review of just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) to promote physical activity. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16, 31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0792-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0792-7