Abstract

Background

Promoting physical activity and healthy eating is important to combat the unprecedented rise in NCDs in many developing countries. Using modern information-and communication technologies to deliver physical activity and diet interventions is particularly promising considering the increased proliferation of such technologies in many developing countries. The objective of this systematic review is to investigate the effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries.

Methods

Major databases and grey literature sources were searched to retrieve studies that quantitatively examined the effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions on physical activity and diet outcomes in developing countries. Additional studies were retrieved through citation alerts and scientific social media allowing study inclusion until August 2016. The CONSORT checklist was used to assess the risk of bias of the included studies.

Results

A total of 15 studies conducted in 13 developing countries in Europe, Africa, Latin-and South America and Asia were included in the review. The majority of studies enrolled adults who were healthy or at risk of diabetes or hypertension. The average intervention length was 6.4 months, and text messages and the Internet were the most frequently used intervention delivery channels. Risk of bias across the studies was moderate (55.7 % of the criteria fulfilled). Eleven studies reported significant positive effects of an e-& mHealth intervention on physical activity and/or diet behaviour. Respectively, 50 % and 70 % of the interventions were effective in promoting physical activity and healthy diets.

Conclusions

The majority of studies demonstrated that e-& mHealth interventions were effective in promoting physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries. Future interventions should use more rigorous study designs, investigate the cost-effectiveness and reach of interventions, and focus on emerging technologies, such as smart phone apps and wearable activity trackers.

Trial registration

The review protocol can be retrieved from the PROSPERO database (Registration ID: CRD42015029240).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2012, about 38 million global deaths were attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer, and it is expected that NCD death rates will increase further, reaching 52 million by 2030. The NCD burden is particularly high in developing countries with 82 % of global NCD-related deaths occurring in low and middle income countries [1, 2].

Major NCD prevention strategies include the reduction of behavioural risk factors, especially physical inactivity and unhealthy diets [1, 3–6]. There is extensive evidence on the preventive effects of regular physical activity and healthy eating on the risk of developing a NCD [7, 8]. For example, a 25 % reduction in physical inactivity is estimated to prevent about 1.3 million NCD-related deaths annually [9] while a healthy diet and increased physical activity can prevent a significant proportion of the 18 million deaths caused by high blood pressure, high body mass index, high fasting blood glucose and high total cholesterol [10].

In developing countries, rapid globalization is contributing to a change in people’s diets where local low calorie and high fibre foods are replaced by readily available, cheap and processed foods high in fat, salt and sugar [8, 11]. For example, in developing countries in Asia, the consumption of processed foods increased by more than 5 % between 1999 and 2012. In contrast, the consumption of processed foods in developed countries increased only by 0.2 % [12]. Additionally, rapid technological development decreases the necessity of physical labour and active transport which in turn contributes to decreasing levels of physical activity [8, 13, 14]. Decreasing physical activity levels were observed in most Asian [15, 16], Latin-and South American [17–19] and some African countries [13, 20] as urbanization increased.

One promising way to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries is to implement electronic and mobile health (e-& mHealth) interventions. These interventions are primarily delivered via modern information and communication technologies (ICT) such as the Internet, mobile phones, and other wireless devices [21]. The proliferation of such ICTs is very high in developing countries. For example, in 2015, 90 % of people living in developing countries owned a mobile phone and two thirds of the global Internet users were based in developing countries [22, 23]. Therefore, it is feasible, and potentially cost-effective, to reach large numbers of people using ICTs in developing countries.

Currently, the evidence on physical activity and behavioural diet e-& mHealth interventions is largely drawn from reviews that did not include studies conducted in developing countries [21, 24, 25]. For example, a recent review on mHealth for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases, only retrieved studies conducted in developed countries [24]. The same applies to reviews focusing on Internet [25, 26], social media [27], smart phone [28, 29], and mobile phone text messaging [30, 31] interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets. Furthermore, a recent review focussing on mHealth interventions in patients with an NCD from developing countries identified only two studies that measured physical activity and none examined dietary behaviours [32]. A systematic review of the research literature on physical activity and diet e-& mHealth interventions conducted in the developing world is currently lacking.

To address this gap, the objective of this systematic review was to investigate the effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries.

Methods

This review was conducted and is reported according to the PRISMA guidelines [33] and the protocol can be retrieved from the PROSPERO database (Registration ID: CRD42015029240).

Study eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they a) quantitatively examined the effect of an e-& mHealth intervention on physical activity and/or diet outcomes; b) were conducted as a quasi-experimental trial, cross-over trial, controlled trial (CT), or randomized controlled trial (RCT); c) included participants from a developing country; and d) were published in English. Only studies in which the e-& mHealth component was the main or a major intervention delivery mode were included. E-& mHealth was defined as the use of ICT to promote physical activity and/or healthy diets. Interventions that were delivered via the Internet (webpages, social media, and email), mobile phone text messages or mobile phone calls, smartphone technology (‘apps’) and other wireless devices (e.g. wearable activity trackers, tablets) were included [21]. The current World Bank classification (July 2015) was used to determine developing country status (low income, lower-middle income, and upper-middle income) [34]. Studies were still included when they were simultaneously conducted in developing and developed countries [35–37]. Every search record was assessed against the inclusion criteria by one of the reviewers (AMM, SA, SS). In cases where study inclusion was unclear a decision was made via discussion including all reviewers.

The primary outcomes of this review were objectively or subjectively measured physical activity and/or dietary behaviour. This could be changes in physical activity levels, time spent doing physical activity, adherence to physical activity recommendations, energy expenditure, step counts, exercise/sport participation, active transport, sedentary time, accelerometer counts; food frequency, diet quality (as defined in the respective studies), fruit and vegetable intake, consumption of sweetened beverages and foods high in sugar, salt or saturated fat (or ultraprocessed foods), dairy product consumption, consumption of fat and dietary fibre, meal size, or caloric intake. Indirect calorimetry, body composition, BMI, body weight, waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, body fat, and lean body mass were reported if available, but only as secondary outcomes.

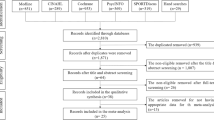

Information sources and search

A systematic search was performed in the following databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA; Cochrane Library), EBSCOHOST (including SPORTDiscuss, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES, Psychology and Behavioral Science Collection), SCOPUS, Web of Science Core Collection and the World Health Organization Global Health Library. For each database, search terms were combined with the appropriate Boolean Operators: technology or email or internet etc. AND physical activity or exercise or walking etc. or healthy eating or nutrition or sugar intake etc. AND developing country or low-income country etc. or Afghanistan or Albania etc. The search period covered the date range 2000 to 31st October 2015 where available in the database. The data base search (Additional file 1 Cochrane Library) was piloted by the corresponding author and reviewed by all co-authors.

Additionally, articles were hand-searched in the grey literature and reference lists of relevant papers were reviewed. Moreover, the Johns Hopkins Global mHealth Initiative was contacted and a request for relevant studies was posted on ResearchGate (social media network for scientists) and created article alerts to derive 2016 articles outside the systematic search to be as current as possible (last inclusion was made in August 2016).

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed based on previous reviews on physical activity and diet interventions [29, 30]. It was piloted on four studies by the corresponding author and refinements were made based on the feedback of the co-authors. Data on study setting/location and participants, e-& mHealth intervention characteristics and intervention effectiveness were retrieved. One reviewer extracted the relevant study information and a second reviewer assessed the data for accuracy and completeness. Disagreement between the reviewers was resolved through discussion and consensus with a third reviewer.

The risk of bias assessment was conducted independently by two reviewers using the CONSORT checklist (AMM, SA) [38] which has been used in previous e-& mHealth reviews [27]. This checklist consists of 25 criteria. If a study fulfilled a criterion it received one point. Studies received half a point if it fulfilled one of two points making up a criterion. A higher overall score indicated lower methodological bias. The obtained risk of bias score of each study was divided by 25 (highest attainable score) and multiplied by 100 to obtain the percentage of fulfilled criteria. Disagreement between the reviewers was resolved through discussion and consensus with a third reviewer (SS). Studies were then grouped into low (>66.7 % fulfilled criteria), moderate (50–66.7 % fulfilled criteria) and high risk of bias (<50 % fulfilled criteria) [25, 39].

If available, changes in physical activity and diet between baseline and intervention completion, and between baseline and final follow-up (period following an intervention) were presented. If possible, effect sizes were reported or calculated (e.g., Cohen’s d, mean difference of change between groups), and confidence intervals and significance levels were presented. Where possible the between group effects were presented. The significance level was set to p ≤ .05.

As few studies provided data needed to calculate effects sizes and due to the great variability in study designs, interventions, and outcome measures conducting a meta-analysis was not possible.

Results

Study selection

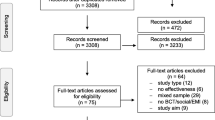

A total of 5961 publications including 2231 duplicates were identified through the date base search. After screening the titles and abstracts of 3858 publications, the full-text of 31 publications was assessed for study eligibility. Of these, 10 publications were included in the review. Another six publications were identified through citation alerts and reference list checks. Finally, two publications reported on the same study [40, 41]. As such, a total of 16 publications describing 15 distinct studies were included in the current systematic review (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Table 1 provides an overview of the study characteristics. The majority were RCTs (n = 8) with two (n = 7) [36, 40, 42–46] or three group study designs (n = 1) [35]. The remaining seven studies were CTs (n = 3) [47–49] or quasi-experimental trials (n = 4) [37, 50–52]. The e-& mHealth interventions lasted between 1 and 24 months (median = 4 months, mean = 6.4 months). In eleven studies physical activity and/or diet outcomes were assessed only at baseline and immediately after the e-& mHealth intervention [35–37, 40, 42, 45, 47–49, 51, 52]. Three studies also conducted follow-up assessments after intervention conclusion (3-month follow-up for all 3 studies) [44, 46, 50] and in one study, physical activity and diet outcomes were assessed at baseline, during the intervention and at intervention completion [43].

One study was conducted in Europe (Turkey) [52], one in Africa (South Africa) [50], three in Latin-or South America (Mexico, Brazil, Peru, and Guatemala) [35, 36, 48], nine in Asia (India, Iran, China, Philippines, Thailand, Pakistan, and Malaysia) [40, 42–47, 49, 51] and one across a large number of countries [37]. Rubinstein et al. [36] conducted their study in Peru, Guatemala and Argentina, Lana et al. [35] in Spain and Mexico, and Ganesan et al., [37] included participants from 64 countries with 92 % from a developing country (mainly India). The number of participants ranged from 22 [50] to 69219 [37] with four trials enrolling less than 100 participants [46, 47, 50, 52]. In total 75930 people participated in all included studies. Fourteen studies enrolled adults over 18 years of age (range = 18 to 74 years), and one study recruited children and adolescents [35]. Study participants were healthy or at risk of developing diabetes or hypertension (n = 10 studies) [35–37, 40, 44, 46, 48, 49, 51, 52] or diabetic (n = 5 studies) [42, 43, 45, 47, 50]. Three studies enrolled only women [44, 50, 52] and one enrolled only men [40].

The e-& mHealth interventions were delivered via mobile phone text messages (n = 7 studies) [36, 40, 42, 43, 46, 49, 50], the Internet including websites and email (n = 6 studies) [35, 37, 44, 48, 51, 52], a website plus mobile phone text messages (n = 1) [35], mobile phone calls (n = 2) [45, 47], or mobile phone calls plus text messages (n = 1) [47]. In eight studies, limited face-to-face contact or printed media were also part of the e-& mHealth intervention [36, 40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 50, 51]. All studies provided information on the intensity of the e-& mHealth intervention. For example, in studies that used mobile phone text-messages as intervention delivery channel text-messaging frequency ranged from twice weekly to daily (mean = 4.5 text messages per week). Only five studies were theoretically framed [35, 36, 40, 44, 48] with the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change most frequently applied (n = 3 studies) [35, 36, 40]. However, in other interventions behaviour change techniques (BCTs) such as goal setting and self-monitoring were used to promote physical activity and healthy diets.

Both physical activity and diet outcomes were assessed in the majority of studies (n = 10) [35, 36, 40, 42, 43, 45, 47, 49, 51, 52] while four assessed only physical activity [37, 44, 46, 50] and one only diet [48]. Physical activity was assessed in various ways, however most studies used a self-report instrument including questionnaires, interviews and exercise diaries (n = 10) [35, 36, 40, 42, 43, 46, 47, 49, 51, 52]. The outcomes also varied greatly across studies: adherence to physical activity guidelines, time spent being active, physical activity-related energy expenditure, physical activity score, and exercise frequency. In one study step-count data were collected with a pedometer [50] while Sriramatr et al. [44] and Ganesan et al. [37] used both pedometer data and a questionnaire. Diet outcomes were only assessed subjectively via questionnaires, 24-h recall sheets and interviews. One study did not report how outcome data was assessed [45]. Secondary outcomes were assessed in ten studies [35–37, 40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 50, 51]. All these studies reported data on BMI and six studies also reported on waist circumference and/or body weight.

Risk of bias within studies

The detailed CONSORT risk of bias assessment of the individual studies is presented in Additional file 2. On average the studies fulfilled 55.7 % of the assessment criteria (range = 28–88 %). Hence, overall the studies had a moderate risk of bias with just over half of the studies at high risk (n = 8 studies) [37, 42, 44, 45, 48, 50–52]. Few studies provided adequate information on intervention harms (n = 2) [40, 46], study protocol publication (n = 3) [35, 36, 51], study registration (n = 6) [35–37, 40, 46, 49], ancillary analyses (n = 5) [35–37, 40, 50], and randomization as well as blinding (n = 4) [36, 40, 43, 46].

Intervention effectiveness

Of the 15 studies included, four reported no significant positive effects on either physical activity or diet outcomes following an e-& mHealth intervention [35, 42, 47, 50]. The majority of studies (n = 11) reported at least one significant positive effect on physical activity or diet outcomes (Table 2). No clear patterns emerged between those studies that were effective and those that were not. In terms of secondary outcomes BMI was measured in nine studies with two reporting a significant positive effect of an e-& mHealth intervention despite not focussing on weight loss [36, 51].

Discussion

Promoting healthy lifestyles is an effective public health strategy to address the NCD rise in developing countries [1]. Given the great proliferation of ICT in developing countries, the use of e-& mHealth approaches appear to be viable to promote physical activity and healthy diets [21–23]. The results of this systematic review suggest that e-& mHealth interventions can be effective in improving physical activity and diet quality in developing countries. Overall, this review showed that 50 % of the e-& mHealth interventions were effective in increasing physical activity, and 70 % of the identified interventions were effective in improving diet quality. This result is consistent with the findings from previous systematic reviews of e-and mHealth interventions conducted in developed countries [21, 24–26, 29, 31, 53–55]. The findings from this review also add to the overall evidence on the effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions in developing countries that were conducted to assess other health outcomes (e.g., treatment adherence) [32, 56–61]. As the included studies used multiple intervention components, it was not possible to identify which specific components were associated with interventions effectiveness. However, most Internet-based interventions were effective in improving physical activity and/or diet while the evidence for mobile-phone interventions (text messages and counselling) was mixed.

The overall risk of bias of the included studies was moderate with just over half of the studies having a high risk of bias. Study quality or study bias are also a concern in studies conducted in developed countries. Most previous reviews on the effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developed countries reported that the included studies were of low to moderate quality or rather biased [28, 30, 55, 62, 63]. There was no association between the risk of bias score and the effectiveness of the e-& mHealth interventions. The four studies with the lowest risk of bias reported mixed results [35, 36, 40, 46] and the same is true for the studies with higher risk of bias.

Importantly, the majority of studies included in this review (n = 10) examined an intervention modality that is likely economically viable and has the potential to reach large numbers of people to address the steep increase of NCDs. While more high-quality RCTs are needed to broaden the evidence-base, it is also important to conduct real-life implementation studies, given that the majority of the included studies reported that the e-& mHealth interventions showed positive outcomes. The study by Ganesan et al. [37] provides an insightful example of real-life implementation of a low-cost e-& mHealth intervention to increase physical activity. The researchers included almost 70000 participants (92 % from developing countries) into their 100-day Stepathlon programme and found that daily step counts and weekly exercise participation increased greatly. This study was possible because academic researchers teamed up with the private sector and formed a strong collaborative network. To form academic-private partnerships in order to either conduct or upscale e-& mHealth interventions to increase physical activity and improve diet quality might also be an option for researchers in other developing countries. Benefits of such partnerships include sharing of expertise (academia: behavioural health knowledge, industry: intervention appeal and dissemination expertise) and data sharing which can lead to dynamic intervention development and adaptation [64]. Potential for such partnerships is especially high in countries where there is some preliminary evidence that such interventions are feasible. Feasibility information is available from Malaysia [65–67], Iraq [68], Pakistan [69] and South Africa [70] where the e-& mHealth interventions were well accepted and study participants found them useful.

A key strength of this review is that this is the first systematic review to investigate the effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries. A further strength is that a large number of information sources were systematically searched to identify relevant studies and that the search was updated continuously (until August 2016). Additionally, data of the included studies were extracted in great detail despite the complex nature of some studies and large variations across studies.

A limitation of this review is that only articles published in English were included. Studies conducted in developing countries where English is not the first language might have been published in local languages and our search would not have identified them. The possibility of publication bias should also be acknowledged. As with all systematic reviews examining the efficacy of interventions, it is possible that some studies that did not find a beneficial effect of an e-& mHealth intervention have not been published [71].

Further, studies were only identified in a small number of countries and it is therefore difficult to generalize the review findings across developing countries (most studies were available from Asia). Additionally, most studies were conducted in upper-middle income countries (n = 10) and none in a low income country.

Due to the differences in study designs, outcome measures, lengths of studies, and study samples it was difficult to draw clear conclusions in this review. It is therefore important that researchers aim to examine the impact of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in a standardized manner. Applying the CONSORT guidelines that specifically highlight the importance of valid controls is strongly encouraged [38]. This will allow for a pooling of results to conduct a meta-analysis, and would reduce the risk of bias in the included studies.

Researchers should be encouraged to assess and report data on intervention acceptability and level of participation (as measured through web and app usage tracking). Only a limited number of studies included in this review presented this information. Knowing how well participants accept and are engaged in e-& mHealth interventions is essential because acceptability and user engagement are related to intervention effectiveness [72, 73]. Additionally, studies examining the cost-effectiveness and reach of e-& mHealth interventions in developing countries are currently lacking. These studies are needed to ensure that resource poor countries can impact health behaviours in a large number of people at an affordable cost. From this review, the impact of behavioural e-& mHealth interventions a) on clinical health outcomes and b) among patients versus non-patients is unclear and more research is warranted.

Finally, while behavioural e-& mHealth research in developed countries is well established [74], research in developing countries is only in its infancy. One indication for this is the small number of studies that were identified. In addition, the studies included in this review utilized mainly first generation technologies of the Internet and mobile phones to implement their interventions (n = 14). However, with the unprecedented expansion of mobile broadband in developing countries, e-& mHealth interventions with advanced technologies (e.g. smart phone apps and wearable activity trackers) [23] are likely to emerge [37]. One feasibility study conducted in South Africa already reported that a diet smartphone app for diabetic nephropathy patients is highly acceptable among dietitians [70]. It is important that researchers examine if these advanced technologies can be leveraged to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries.

Conclusions

In summary, using e-& mHealth approaches to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries was effective in most studies included in this review. However, the interventions varied greatly in terms of geographic spread, intervention components evaluated, trial methods applied and study quality. Therefore, the findings from the included studies should be interpreted with caution, and more rigorous study designs are recommended for future e-& mHealth interventions.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- CT:

-

Controlled trial

- e-& mHealth:

-

Electronic and mobile health

- ICT:

-

Information and communication technology

- MET:

-

Metabolic Equivalent of task

- NCD:

-

Non-communicable disease

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 .

Horton R. Non-communicable diseases: 2015 to 2025. Lancet. 2013;381(9866):509–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60100-2 .

Balbus JM, Barouki R, Birnbaum LS, Etzel RA, Gluckman PD, Grandjean P, et al. Early-life prevention of non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2013;381(9860):3–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61609-2 .

Mishra SR, Neupane D, Preen D, Kallestrup P, Perry HB. Mitigation of non-communicable diseases in developing countries with community health workers. Global Health. 2015;11:43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12992-015-0129-5 .

Lachat C, Otchere S, Roberfroid D, Abdulai A, Aguirre Seret FM, Milesevic J, et al. Diet and physical activity for the prevention of noncommunicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic policy review. PLoS Med. 2013;10(6):e1001465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001465 .

Shiroma EJ, Lee I. Physical activity and cardiovascular health: lessons learned from epidemiological studies across age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Circulation. 2010;122(7):743–52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914721 .

Popkin BM. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):289–98.

Lee I, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9 .

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8 .

Steyn NP, McHiza ZJ. Obesity and the nutrition transition in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1311:88–101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12433 .

Baker P, Friel S. Processed foods and the nutrition transition: evidence from Asia. Obes Rev. 2014;15(7):564–77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/obr.12174 .

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U, et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):247–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1 .

Goryakin Y, Lobstein T, James WPT, Suhrcke M. The impact of economic, political and social globalization on overweight and obesity in the 56 low and middle income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:67–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.030 .

Macniven R, Bauman A, Abouzeid M. A review of population-based prevalence studies of physical activity in adults in the Asia-Pacific region. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):41–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-41 .

Ranasinghe CD, Ranasinghe P, Jayawardena R, Misra A. Physical activity patterns among South-Asian adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-116 .

Amorim TC, Azevedo MR, Hallal PC. Physical activity levels according to physical and social environmental factors in a sample of adults living in South Brazil. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7 Suppl 2:S204–12.

Masterson Creber RM, Smeeth L, Gilman RH, Miranda JJ. Physical activity and cardiovascular risk factors among rural and urban groups and rural-to-urban migrants in Peru: A cross-sectional study. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2010;28:1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2957283/.

Bauman A, Bull F, Chey T, Craig CL, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, et al. The international prevalence study on physical activity: results from 20 countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-21 .

Abubakari AR, Lauder W, Jones MC, Kirk A, Agyemang C, Bhopal RS. Prevalence and time trends in diabetes and physical inactivity among adult West African populations: the epidemic has arrived. Public Health. 2009;123(9):602–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2009.07.009 .

Vandelanotte C, Müller AM, Short CE, Hingle M, Nathan N, Williams SL, et al. Past, present and future or e- & mHealth research to improve physical activity and dietary behaviors. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(3):219–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2015.12.006 .

International Telecommunication Union. The world in 2014: ICT facts and figures. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union; 2014.

International Telecommunication Union. ICT facts and figures. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union; 2015.

Burke LE, Ma J, Azar KMJ, Bennett GG, Peterson ED, Zheng Y, et al. Current science on consumer use of mobile health for cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(12):1157–213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000232 .

Davies CA, Spence JC, Vandelanotte C, Caperchione CM, Mummery WK. Meta-analysis of internet-delivered interventions to increase physical activity levels. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-52 .

Hou S, Charlery SR, Roberson K. Systematic literature review of Internet interventions across health behaviors. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014;2(1):455–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2014.895368 .

Maher CA, Lewis LK, Ferrar K, Marshall S, Bourdeaudhuij I, Vandelanotte C. Are health behavior change interventions that use online social networks effective? A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e40. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2952 .

Flores Mateo G, Granado-Font E, Ferré-Grau C, Montaña-Carreras X. Mobile phone apps to promote weight loss and increase physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(11):e253. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4836 .

Bort-Roig J, Gilson ND, Puig-Ribera A, Contreras RS, Trost SG. Measuring and influencing physical activity with smartphone technology: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2014;44(5):671–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0142-5 .

Siopis G, Chey T, Allman-Farinelli M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions for weight management using text messaging. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015;28(2):1–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12207 .

Weber Buchholz S, Wilbur J, Ingram D, Fogg L. Physical activity text messaging interventions in adults: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2013;10(3):163–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12002 .

Stephani V, Opoku D, Quentin W. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of mHealth interventions against non-communicable diseases in developing countries. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3226-3 .

Liberati A. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):65–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136 .

World Bank [Internet]. Country and Lending Groups [cited October 8, 2015]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups.

Lana A, Faya-Ornia G, López ML. Impact of a web-based intervention supplemented with text messages to improve cancer prevention behaviors among adolescents: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2014;59:54–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.11.015 .

Rubinstein A, Miranda JJ, Beratarrechea A, Diez-Canseco F, Kanter R, Gutierrez L, et al. Effectiveness of an mHealth intervention to improve the cardiometabolic profile of people with prehypertension in low-resource urban settings in Latin America: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(1):52–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00381-2 .

Ganesan AN, Louise J, Horsfall M, Bilsborough SA, Hendriks J, McGavigan AD, et al. International mobile-health intervention on physical activity, sitting, and weight: the Stepathlon cardiovascular health study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(21):2453–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.472 .

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Medicine. 2010;8:18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-8-18 .

Schoeppe S, Duncan MJ, Badland H, Oliver M, Curtis C. Associations of children’s independent mobility and active travel with physical activity, sedentary behaviour and weight status: a systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2013;16(4):312–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2012.11.001 .

Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Ram J, Selvam S, Simon M, Naditha A, et al. Effectiveness of mobile phone messaging in prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle modification in men in India: a prospective, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(3):191–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70067-6 .

Ram J, Selvam S, Snehalatha C, Naditha A, Simon M, Shetty AS, et al. Improvement in diet habits, independent of physical activity helps to reduce incident diabetes among prediabetic Asian Indian men. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106(3):491–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2014.09.043 .

Shetty AS, Chamukuttan S, Nanditha A, Raj RK, Ramachandran A. Reinforcement of adherence to prescription recommendations in Asian Indian diabetes patients using short message service (SMS)–a pilot study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:711–4.

Tamban C, Isip-Tan IT, Jimeno C. Use of short message services (SMS) for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2013;28(2):143–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.15605/jafes.028.02.08 .

Sriramatr S, Berry TR, Spence JC. An Internet-based intervention for promoting and maintaining physical activity: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(3):430–9.

Shahid M, Mahar SA, Shaikh S, Shaikh ZU. Mobile phone intervention to improve diabetes care in rural areas of Pakistan: a randomized controlled trial. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25(3):166–71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25772954.

Müller AM, Khoo S, Morris T. Text messaging for exercise promotion in older adults from an upper-middle-income country: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(1):e5. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5235 .

Zolfaghari M, Mousavifar SA, Pedram S, Haghani H. The impact of nurse short message services and telephone follow‐ups on diabetic adherence: which one is more effective? J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(13–14):1922–31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03951.x .

Bombem KCM, Silva Canella D, Henrique Bandoni D, Constante Jaime P. Impact of an educational intervention using e-mail on diet quality. Nutr Food Sci. 2014;44(5):431–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/NFS-02-2013-0034 .

Pfammatter A, Spring B, Saligram N, Dave R, Gowda A, Blais L, et al. mHealth intervention to improve diabetes risk behaviors in India: a prospective, parallel group cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(8):e207. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5712 .

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tomlinson M, Gwegwe M, Comulada WS, Kaufman N, Keim M. Diabetes buddies: peer support through a mobile phone buddy system. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(3):357–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0145721712444617 .

Chen P, Chai J, Cheng J, Li K, Xie S, Liang H, et al. A smart web aid for preventing diabetes in rural China: preliminary findings and lessons. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(4):e98. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3228 .

Nurgul K, Nursan C, Dilek K, Over OT, Sevin A. Effect of web-supported health education on knowledge of health and healthy-living behaviour of female staff in a turkish university. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;16(2):489–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.2.489 .

Head KJ, Noar SM, Iannarino NT, Grant Harrington N. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:41–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.003 .

Fanning J, Mullen SP, McAuley E. Increasing physical activity with mobile devices: a meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e161. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2171 .

Lewis ZH, Lyons EJ, Jarvis JM, Baillargeon J. Using an electronic activity monitor system as an intervention modality: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1947-3 .

Gurman TA, Rubin SE, Roess AA. Effectiveness of mHealth behavior change communication interventions in developing countries: a systematic review of the literature. J Health Commun. 2012;17(1):82–104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.649160 .

Déglise C, Suggs LS, Odermatt P. Short message service (SMS) applications for disease prevention in developing countries. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1):e3. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1823 .

Bloomfield GS, Vedanthan R, Vasudevan L, Kithei A, Were M, Velazquez EJ. Mobile health for non-communicable diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of the literature and strategic framework for research. Global Health. 2014;10:49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-10-49 .

Hall CS, Fottrell E, Wilkinson S, Byass P. Assessing the impact of mHealth interventions in low-and middle-income countries–what has been shown to work? Glob Health Action. 2014;7:256060. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.25606 .

Peiris D, Praveen D, Johnson C, Mogulluru K. Use of mHealth systems and tools for non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2014;7(8):677–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12265-014-9581-5 .

Beratarrechea A, Lee AG, Willner JM, Jahangir E, Ciapponi A, Rubinstein A. The impact of mobile health interventions on chronic disease outcomes in developing countries: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(1):75–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2012.0328 .

Lyzwinski LN. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mobile devices and weight loss with an intervention content analysis. J Pers Med. 2014;4(3):311–85. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/jpm4030311 .

O’Reilly GA, Spruijt-Metz D. Current mHealth technologies for physical activity assessment and promotion. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(4):501–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.012 .

Hingle M, Patrick H. There are thousands of apps for that: navigating mobile technology for nutrition education and behavior. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(3):213–218.e1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2015.12.009 .

Ramadas A, Chan CKY, Oldenburg B, Hussien Z, Quek KF. A web-based dietary intervention for people with type 2 diabetes: development, implementation, and evaluation. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(3):365–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12529-014-9445-z .

Ang YK, Mirnalini K, Zalilah MS. A workplace email-linked website intervention for modifying cancer-related dietary and lifestyle risk factors: rationale, design and baseline findings. Malays J Nutr. 2013;19(1):37–51.

Noah SA, Abdullah SN, Shahar S, Abdul-Hamid H, Khairudin N, Yusoff M, et al. DietPal: a Web-based dietary menu-generating and management system. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(1):e4.

Haddad NS, Istepanian R, Philip N, Khazaal FA, Hamdan TA, Pickles T, et al. A feasibility study of mobile phone text messaging to support education and management of type 2 diabetes in Iraq. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2014;16(7):454–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/dia.2013.0272 .

Hussain MI, S Naqvi B, Ahmed I, Ali N. Hypertensive patients’ readiness to use of mobile phones and other information technological modes for improving their compliance to doctors’ advice in Karachi. Pak J Med Sc. 2015;31(1):9–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.12669/pjms.311.5469 .

Esau N, Koen N, Herselman MG. Adaptation of the RenalSmart® web-based application for the dietary management of patients with diabetic nephropathy. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2013;26(3):132–40.

Hopewell S, Loudon K, Clarke MJ, Oxman AD, Dickersin K. Publication bias in clinical trials due to statistical significance or direction of trial results. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:MR000006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000006.pub3.

Short CE, Rebar AL, Plotnikoff RC, Vandelanotte C. Designing engaging online behaviour change interventions: A proposed model of user engagement. Eur Health Psychol. 2015;17(1):32–8.

Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, Muller I. The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(1):e30. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4055 .

Hall AK, Cole-Lewis H, Bernhardt JM. Mobile text messaging for health: a systematic review of reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:393–415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122855 .

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

CV was supported by a Future Leader Fellowship from the National Heart Foundation of Australia (ID 100427). The funder had no role in any part of the study.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article (and its Additional files 1 and 2).

Authors’ contributions

AMM developed the concept and design of the study, provided the systematic literature research and drafted the manuscript. AMM, SS and SA extracted the data and rated the risk of bias of individual studies. AMM, SS, SA and CV contributed to the development of the study protocol, interpretation of the data and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Cochrane Library Complete Search Strategy. (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 2:

Risk of bias assessment using the CONSORT checklist. (DOCX 32 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller, A.M., Alley, S., Schoeppe, S. et al. The effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries: A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 13, 109 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0434-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0434-2