Abstract

Background

Until now, there is no clear overview of how fidelity is assessed in school-based obesity prevention programmes. In order to move the field of obesity prevention programmes forward, the current review aimed to 1) identify which fidelity components have been measured in school-based obesity prevention programmes; 2) identify how fidelity components have been measured; and 3) score the quality of these methods.

Methods

Studies published between January 2001–October 2017 were selected from searches in PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and ERIC. We included studies examining the fidelity of obesity prevention programmes (nutrition and/or physical activity and/or sitting) at school (children aged 4–18 year) measuring at least one component of implementation fidelity. A data extraction was performed to identify which and how fidelity components were measured. Thereafter, a quality assessment was performed to score the quality of these methods. We scored each fidelity component on 7 quality criteria. Each fidelity component was rated high (> 75% positive), moderate (50–75%) or low (< 50%).

Results

Of the 26,294 retrieved articles, 73 articles reporting on 63 different studies were included in this review. In 17 studies a process evaluation was based on a theoretical framework. In total, 120 fidelity components were measured across studies: dose was measured most often (N = 50), followed by responsiveness (N = 36), adherence (N = 26) and quality of delivery (N = 8). There was substantial variability in how fidelity components were defined as well as how they were measured. Most common methods were observations, logbooks and questionnaires targeting teachers. The quality assessment scores ranged from 0 to 86%; most fidelity components scored low quality (n = 77).

Conclusions

There is no consensus on the operationalisation of concepts and methods used for assessing fidelity in school-based obesity prevention programmes and the quality of methods used is weak. As a result, we call for more consensus on the concepts and clear reporting on the methods employed for measurements of fidelity to increase the quality of fidelity measurements. Moreover, researchers should focus on the relation between fidelity and programme outcomes and determine to what extent adaptations to programmes have been made, whilst still being effective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

To combat the worldwide childhood overweight and obesity epidemic, a large variety of healthy eating and physical activity promotion programmes targeting youth have been developed [1]. Schools are regarded as a suitable setting for obesity prevention programmes, as they provide access to almost all children, regardless of their ethnicity or socio economic status [2]. School-based obesity prevention programmes that target healthy eating, physical activity and sedentary behaviour seem promising in reducing or preventing overweight and obesity among children [1, 3, 4]. However, when those evidence-based programmes are implemented in real world settings, their effectiveness is often disappointing [5]. One of the reasons is that programmes are not implemented in the same way as intended by programme developers, which could be labelled as a ‘lack of fidelity’ or ‘programme failure’ [5]. On the other hand, some degree of programme adaptation is inevitable and may actually have beneficial effects [6]. A better understanding of implementation processes is important to determine if and when disappointing effects can be ascribed to programme failure.

Although there is growing recognition for conducting comprehensive process evaluations, most studies are still focused on studying programme effectiveness and process evaluations are often an afterthought [7]. We believe that it is not only important to evaluate if a programme was effective, but also to understand how a programme was implemented and how this affected programme outcomes starting in the early stages of intervention development and evaluation [8]. The literature distinguishes the following four evaluation phases: 1) Formative evaluation: evaluate the feasibility of a health programme, 2) Efficacy evaluation: evaluate the effect of a health programme under controlled conditions (internal validity), 3) Effectiveness evaluation: evaluate the effect of a health programme under normal conditions (internal and external validity) and 4) Dissemination evaluation: evaluate the adoption of a large, ongoing health programme in the real world [9, 10]. Although there are differences in the scope of each evaluation phase, process evaluations can support studies in each phase by providing a detailed understanding about implementers’ needs, the implementation processes, specific programme mechanisms of impact and contextual factors promoting or inhibiting implementation [8, 10].

One of the aspects captured in process evaluations is fidelity [5, 11,12,13]. Fidelity is an umbrella term for the degree to which an intervention was implemented as intended by the programme developers [11]. Measurements of fidelity can inform us what was implemented and how it was done as well as what changes were made to the programme (i.e. what adaptations), and how these adaptations could have influenced effectiveness [11]. Until recently many claimed that all forms of adaptation indicate a lack of fidelity and, therefore, a threat to programme effectiveness [11, 12, 14, 15]. However, there is increasing recognition for the importance of mutual adaptation between the programme developers (e.g. researchers) and programme providers (e.g. student, teacher, school director) [11, 16]. Mutual adaptation indicates a bidirectional process in which a proposed change is modified to the needs, interests and opportunities of the setting in which the programme is implemented [11]. Wicked problems such as obesity require that programme developers are open to (major) bottom-up input and adjustments without controlling top-down influence [17]. Hence, this implies the need to accurately determine whether programmes were adapted and to measure fidelity and relate this to programme outcomes [10].

Several frameworks have been proposed and applied to measure fidelity in health-promotion programme evaluations [11, 18, 19]. For example, the Key process evaluation components defined by Linnan and Steckler [19] and the Conceptual framework for implementation fidelity by Carroll et al. [18]. Yet, there is much heterogeneity in the operationalisation and measurement of the concept of fidelity [20]. While some focus on quantitative aspects of fidelity, such as the dose delivered to the target group expressed in a percentage of use, others focus on if the programme was implemented as intended, often also operationalised as ‘adherence’ [11, 12, 18, 21]. Moreover, methods to measure fidelity may vary significantly in quality. While some focus on the use of teacher self-reports conducted at programme completion, others focus on the use of observer data during the implementation period which appears to be more valid [11]. No standardised operationalisation and methodology exists for measuring fidelity, partially due to the complexity and variety of school-based obesity prevention programmes.

In 2003, Dusenbury et al. reviewed the literature on implementation fidelity of school-based drug prevention programmes spanning a 25-year period [11]. According to their review, fidelity can be divided into five components: 1) adherence (i.e. the extent to which the programme components were conducted and delivered according the theoretical guidelines, plan or model); 2) dose (i.e. the amount of exposure to programme components received by participants, like the amount or the duration of the lessons that were delivered); 3) quality of programme delivery (i.e. how programme providers delivered the programme components, for example the teacher’s enthusiasm, confidence or way of telling); 4) participant responsiveness (i.e. the extent to which the participants are engaged with the programme, for example their enthusiasm, their interest in the programme or their willingness to participate); and 5) programme differentiation (i.e. the identification of essential programme components for effective outcomes) [11].

Until now, there is no clear overview of how fidelity is assessed in school-based obesity prevention programmes. In order to move the field of obesity prevention programmes forward, we reviewed the literature to identify the current methods used to operationalise, measure and report measures of fidelity. Building on the conceptualization of the elements of fidelity by Dusenbury, the aims of this review are to: 1) identify which fidelity components have been measured in school-based obesity prevention programmes; 2) identify how fidelity components have been measured; and 3) score the quality of these methods.

Methods

Literature search

A literature search was performed by RO, RS and FvN, based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)-statement, see Additional file 1. To identify all relevant publications, we performed systematic searches in the bibliographic databases PubMed, EMBASE.com, Cinahl (via Ebsco), The Cochrane Library (via Wiley), PsycINFO (via EBSCO) and ERIC (via EBSCO) from January 2001 up to October 2017. Search terms included controlled terms (MeSH in PubMed and Emtree in Embase etc.) as well as free text terms. We used free text terms only in The Cochrane Library.

The search strategy focused on search terms standing for the target setting (e.g. ‘school’), in AND-combination with terms for measures of fidelity (e.g. ‘adherence’ OR ‘dose’), the target group (e.g. ‘child’), and on health promotion interventions (e.g. ‘health promotion’ OR ‘program’). This search was enriched with OR-combination with terms for at least one energy balance-related behaviour (e.g. ‘sitting’ OR ‘physical activity’ OR ‘eating’) or obesity (e.g. ‘obesity’ OR ‘overweight’). The full search strategy for all databases can be found in the appendix, see Additional file 2.

Selection process

The following inclusion criteria were applied: 1) a population of school-aged children (4–18 years), 2) a school-based intervention that prevents obesity (sitting, nutrition and/or physical activity), 3) at least one fidelity component of Dusenbury et al. [11] as an outcome measure, 4) evaluating fidelity with quantitative methods – i.e. questionnaires, observations, structured interviews or logbooks. The following exclusion criteria were applied: 1) a population of younger (< 4 years) or older children (> 18 years); 2) evaluating programmes that were only implemented after school time; 3) evaluating fidelity with qualitative methods only. Only full text articles published in English and all studies describing elements of fidelity were included, irrespective of the maturity of the study phase (i.e. Formative evaluation, Efficacy evaluation, Effectiveness evaluation and Dissemination evaluation) [9, 10]. Two reviewers (RS, FvN) independently checked all retrieved titles and abstracts and independently reviewed all selected full text articles. Disagreements were resolved until consensus was reached. Finally, the reference lists of the selected articles were checked for relevant studies.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed to identify which and how fidelity components were measured. In the data extraction information was collected on author, programme name, year of publication, country of delivery, programme characteristics, setting, target group, programme provider, theoretical framework and measures of implementation fidelity. We used the classification of Dusenbury et al. [11] to review measures of implementation fidelity in school-based obesity prevention programmes. For each measured fidelity component (i.e. adherence, dose, quality of delivery, responsiveness, and differentiation), we extracted the following data: definition of fidelity component, data collection methods and timing, subject of evaluation (i.e. student, teacher or school), a summary of the results (i.e. mean value or range) and the relation between a fidelity component and programme outcome. One reviewer (RS) performed the data extraction. Thereafter, the data extraction was checked by a second reviewer (FvN). Disagreements between the reviewers with regard to the extracted data were discussed until consensus was reached. Results are reported per study, this means that if two articles reported about the same study trial, we merged the results. Studies describing the same programme but evaluated in different study trials were separately reported in the data extraction tables. Moreover, if the study referred to another publication describing the design or other relevant information about the study in question, the additional publication was read to perform additional data extraction. Three different authors were contacted by email to ask for additional information on the data extraction.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment was performed to score the quality of methods used to measure each specific fidelity component (i.e. adherence, dose, quality of delivery, responsiveness and differentation) for each study. Two reviewers (RS and FvN) independently performed the methodological quality assessment. Disagreements were discussed and resolved. Given the absence of a standardized quality assessment tool for measuring implementation fidelity, the quality assessment was based on a tool that was used in two reviews also looking at process evaluation data [7, 22]. The quality of methods was scored by the use of 7 different criteria (see Table 1). As a first step, we assessed if the 7 criteria had been applied to each of the measured fidelity components in each study. Per fidelity component, each criterion was scored either positive (+) or negative (−) (see Table 1). However, this was slightly different for the fidelity components adherence and quality of delivery. For those components, the score not applicable (NA) was applied on criterion number two (i.e. level of evaluation), as it is not possible to evaluate these fidelity components on two or more levels – i.e. only on teacher level.

Secondly, based on the scores of the 7 criteria, a sum quality score (percentage of positive scores of the 7 criteria) was calculated for each fidelity component for each study, resulting in a possible score of 0% (7 criteria scored negative) to 100% (7 criteria scored positive). The scoring procedure was slightly different for the fidelity components adherence and quality of delivery. Adherence and quality of delivery scored not applicable on criterion number two. Consequently, for these two fidelity components a sum quality score was calculated on the basis of 6 criteria. Which means that these components received 0% if 6 criteria were scored negative and 100% if 6 criteria were scored positive. Finally, each fidelity component was rated as having a high (> 75% positive), moderate (50–75% positive) or low (< 50% positive) methodological quality.

Results

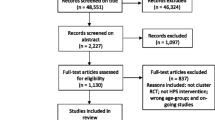

In total 26,294 articles of potential interest were retrieved: 9408 in EMBASE, 6957 in PubMed, 2504 in CINAHL, 3115 in PsycINFO, 2227 in Cochrane and 2083 in ERIC. After further selection based on first title and abstract and subsequently full text, 73 published articles [21, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] reporting on 63 different studies were included. Reasons for excluding articles are reported in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

In the following section we will describe the study characteristics and describe which fidelity components have been measured in the included studies (Aim 1). Table 2 provides an overview of the study characteristics and measured fidelity components (i.e. adherence, dose, quality of delivery, responsiveness or differentiation) including references. Studies were conducted in 12 different countries, but were mostly conducted in the United States (N = 31) and in the Netherlands (N = 11). Two studies were conducted in a combination of multiple European countries. All studies were aimed to prevent obesity, wherein 16 studies targeted physical activity, 27 studies targeted healthy eating, 12 studies targeted both physical activity and healthy eating, three studies targeted both physical activity and sedentary behaviour and five studies targeted physical activity, healthy eating and sedentary behaviour. In total 45 studies were conducted in primary schools, 12 in secondary schools and six both in primary and secondary schools. The use of a theory, framework or model for designing process evaluations was applied in 17 studies. Nine different theories, framework or models were used; Key process evaluation components defined by Steckler and Linnan, Concepts in process evaluations by Baranowski and Stables, Conceptual framework of process evaluations by Mcgraw, How to guide for developing a process evaluation by Saunders, Logic model by Scheirer, RE-AIM framework by Glasgow, Probabilistic mechanistic model of programme delivery by Baranowski and Jago, Taxonomy of outcomes for implementation research by Proctor and Theory of diffusion of innovations by Rogers.

In total, 63 studies reported 120 fidelity components. Dose was measured most often (N = 50), followed by responsiveness (N = 36), adherence (N = 26), and quality of delivery (N = 8). The fidelity component differentiation was not measured in any of the studies. In 24 studies only one fidelity process component was measured. Two components were measured in 22 studies and three components were measured in 16 studies. Only one study measured four fidelity components, meaning that no study measured all five fidelity components.

In the following sections, each of the measured fidelity components are described in more detail. We describe how fidelity components were measured (Aim 2) and the quality scores for these methods (Aim 3). Tables 3 and 4 provide an overview on the measurements of the fidelity components including references. The full data extraction and quality assessment can be found in the appendix, see Additional files 3 and 4.

Adherence

The component adherence was reported in 26 studies (see Table 2). A definition of adherence was provided and defined or operationalised in 15 studies. Adherence was mostly defined as fidelity, programme carried out, delivered or intended as planned. Measurements of adherence were mostly conducted with observations (N = 15), followed by logbooks (N = 10), questionnaires (N = 7) and structured interviews (N = 2) (see Table 3). Teachers were in almost all cases the subject of evaluation, while schools (i.e. school leaders) were reported in one study. Regarding frequency of data collection, 22 studies measured adherence on more than one occasion (see Table 4). Adherence was related five times to programme outcomes.

Quality scores of adherence ranged from 17 to 83% and the mean score was 46%. Adherences scored 11 times low, 11 times moderate and four times high methodological quality (see Table 4). Adherence scored the highest on criterion six (i.e. frequency of data collection) and the lowest on criterion seven (i.e. fidelity component related to programme outcome), as in only five studies the relation between a fidelity component and programme outcome was assessed.

Dose

The component dose was reported in 50 studies (see Table 2). A definition of dose was defined or operationalised in 28 studies. Dose was mostly defined as the proportion, amount, percentage or number of activities or components that were delivered, used or implemented. Measurements of dose were conducted by means of questionnaires (N = 27), logbooks (N = 24), observations (N = 7) and structured interviews (N = 6) (see Table 3). In one study the method was not reported [23]. In 40 studies, the subject of evaluation was a teacher, in ten studies a student and only in one study a school. Regarding frequency, 34 studies measured dose on more than one occasion (see Table 4). Dose was related 17 times to programme outcomes.

Quality scores of dose ranged from 0 to 86% and the mean score was 37%. Dose scored 34 times low, 14 times moderate and two times high methodological quality (see Table 4). Dose obtained the highest scores on criterion number six (i.e. frequency of data collection) and the lowest on criterion number two (i.e. level of evaluation), as in only two studies the level of evaluation was on two or more levels.

Quality of delivery

Quality of delivery was measured in eight studies (see Table 2). Five of those studies that defined or operationalised quality of delivery, referred to it as the quality of the programme. For example, studies measured if teachers were prepared for their lessons, their way of communicating to children or their level of confidence to demonstrate lessons. Conducted measurements methods were questionnaires (N = 3), logbooks (N = 3) and observations (N = 2) (see Table 3). All studies were performed on teacher level and almost all studies, except for two, performed measurements on multiple occasions (see Table 4). Quality of delivery was related twice to programme outcomes.

Quality scores of quality of delivery ranged from 17 to 67% and the mean score was 46%. Quality of delivery scored three times low and five times moderate methodological quality (see Table 4). Quality of delivery obtained the highest score on criterion number six (i.e. frequency of data collection) and obtained the lowest score on criterion number four (i.e. data collection methods), because only one study reported the use of more than one technique for data collection.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness was measured in 36 studies (see Table 2). The definition of responsiveness was defined or operationalised in 13 studies. Responsiveness was generally defined as satisfaction, appreciation, acceptability, or enjoyment of the programme. Measurements of responsiveness were mostly conducted with questionnaires (N = 34), followed by observations (N = 5), logbooks (N = 3) and structured interviews (N = 1) (see Table 3). The subject of evaluation was 31 times on student level and 17 times on teacher level. Hereby, measurements were in 14 studies on multiple occasions (see Table 4). Responsiveness was related seven times to programme outcomes.

Quality scores of responsiveness ranged from 0 to 86% and the mean score was 34%. Responsiveness scored 29 times weak, 6 times moderate and 1 time high methodological quality (see Table 4). Responsiveness scored the highest on criterion number five (i.e. quantitative fidelity measures) and scored the lowest on criterion number four (i.e. data collection methods), because only five studies reported the use of multiple data collection methods.

Discussion

This review aimed to gain insight in the concepts and methods employed to measure fidelity and to gain insight into the quality of measuring fidelity in school-based obesity prevention programmes. The results of this review indicate that measurements of fidelity are multifaceted, encompassing different concepts and varying operationalisation of fidelity components. Moreover, methods were conducted in a range of different ways and mostly conducted with a low methodological quality.

The studies included in our review used different ways to define fidelity and its components in school-based obesity prevention programmes. One of the main concerns is that definitions of fidelity components were used interchangeably and were inconsistent. The same definition was used for different fidelity components. For example, adherence and dose were both defined as ‘implementation fidelity’. Definitions, if provided, were rather short and 59 of the 120 fidelity components were not accurately defined, meaning that only the ‘name’ of the component was mentioned and no further explanation was provided on how authors defined the measured component. This lack of consistency in fidelity components definitions is in line with other reviews in implementation science [11, 95] and may be due to the small amount of studies that base their process evaluation on a theory, framework or model [96].

Related to that issue, no standardised theory, framework or model exists for the guidance of measuring fidelity in school-based obesity prevention programmes [96]. As a result, process evaluation theories, frameworks or models from different research areas were implemented, which may also contribute to inconsistent fidelity component definitions. For example, Concepts in process evaluations by Baranowski and Stables originated from health promotion research [65], while the Taxonomy of outcomes for implementation research by Proctor originated from quality of care research [13]. Thus, researchers in implementation science need to agree upon the definitions employed for fidelity components, base their design for fidelity measurements on a theory, framework or model and describe this design and included fidelity components thoroughly.

According to Dusenbury et al. [11], fidelity has generally been operationalized in five components; 1) adherence, 2) dose, 3) quality of delivery, 4) responsiveness and 5) differentiation. In line with their findings, the current review showed that the amount and type of fidelity components measured in the included studies varied a lot, with most studies only assessing one to three components. Moreover, the majority of the studies only investigated dose, which reflects often primary interest of researchers in actual programme delivery and participation levels, rather than an interest in how a programme was delivered (i.e. quality of delivery). None of the studies measured the unique programme components, operationalized as differentiation by Dusenbury et al. [11]. One explanation could be that it is very complex to measure differentiation in school-based obesity prevention programmes, as they usually include many different interacting programme components which as a whole contribute to programme outcomes.

The finding that no study assessed every component of fidelity as defined by Dusenbury et al. [11] confirms previous findings [20]. Although, it can be argued that measurements of all fidelity components can provide a full overview of the degree to which programmes are implemented as planned [12]. This may often be unfeasible as the choice for which fidelity components to include in process evaluations is partially dependent on the context, resource constraints and measurement burden [10]. As such, measurements for fidelity are determined through both a top-down and bottom-up approach, which include programme developers, and programme providers. Additionally, the claim that measurements of all fidelity components is of importance, could also be debated by the fact that it is still unknown which of the fidelity components contributes most to positive programme outcomes. Subsequently, often too much focus is given on measuring as much fidelity components as possible, which could decrease the quality of fidelity measurements. Therefore, we may learn most from carefully selecting and measuring most relevant components with high quality. This may bring us one step further in learning more about the relation between fidelity components and positive programme outcomes.

Most components scored low methodological quality (i.e. 77 fidelity components). Especially methods employed to measure a fidelity component scored low. While measurements of fidelity components were performed with a wide variety of techniques (i.e. observations, questionnaires, structured interviews or logbooks), the majority of the studies lacked data triangulation and the employed methods were often not measured on two or more levels (i.e. teacher, student or school). A possible explanation could be that process evaluations of high quality may not always be practical to fulfil in real-world settings [97]. Herein, researchers need to balance between high quality methods and keeping the burden for participants and researchers low. Therefore, the complexity of school-based obesity prevention programmes may play a role in the quality of methods that are conducted in process evaluations [10]. Another explanation could be that many studies focus more on effect outcomes than on process measures. A multifaceted approach, encompassing both outcome and process measures, is needed as implementation of school-based obesity prevention programmes is a complex process [10]. Thus, we need to stimulate researchers to focus more on process measures encompassing more high-quality methods with a focus on data triangulation and measurements conducted on different levels.

Studies barely discussed the validity or reliability of measures used for measuring fidelity. This may be due to the fact that process evaluations are scarcely validated and are often adapted to the setting in which a programme is implemented. Identification and knowledge of strong validated instruments in the field of implementation science is limited. In a response to this lack of knowledge, the Society for Implementation Research Collaboration (SIRC) systematically reviewed quantitative instruments assessing fidelity [98]. Their review is a relevant and valuable resource for identifying more high-quality instruments. In addition, the SIRC also provides information on the use of these instrument in certain contexts, which is of importance for implementation research in real-world settings. Hence, to move the field of implementation science forward, future studies need to report in detail which methods were used for measuring fidelity and the inherent strengths and limitations of these methods and even more of importance is that journals support publication of these types of articles.

The importance for relating fidelity to programme outcomes in school-based obesity programmes is increasingly recognised [10, 20]. The majority of studies included in this review did not investigate the relation between components of fidelity and programme outcomes, which is in line with conclusions of other studies [20]. The investigation of this relation is of importance, as high fidelity simply does not exist in real practice; programmes that were adapted to the setting in which they were implemented (i.e. mutual adaptation) were more effective than programmes that were implemented as intended (i.e. high fidelity) [11]. More flexibility in programme delivery could address the needs of the target group or context in which the programme is implemented and may increase the likelihood that the programme will be adopted in real practice and, thereby, result in more positive outcomes [11, 99]. Though, process evaluations included in our review were often part of an RCT (i.e. implementation during controlled conditions) and were mainly focused on investigating the effectiveness of a programme as the main outcome. Randomisation is however often not desirable nor feasible in real world obesity prevention approaches [100]. Instead, more research is needed looking at the degree of implementation in real world settings and to what extent adaptations to the programme have been made, and how this impacted the implementation and sustainability of changes.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducting a systematic review to provide an overview of methods used for measuring fidelity in school-based obesity prevention programmes. Other strengths are the use of the framework of Dusenbury et al. [11] to conceptualise fidelity, systematically select studies, data extraction and quality assessment performed with two reviewers independently. However, there are also some limitations of this review that should be acknowledged. First, formative evaluation or effectiveness evaluation studies may not have reported their process evaluations in the title or abstract, as implementation is rarely a key focus of school-based obesity prevention programmes. As a result, some relevant studies may have been missed. Nevertheless, we included a large number of studies, therefore, we assume that this review provides a good overview of fidelity in school-based obesity prevention programmes. Another limitation is the possibility that we have overlooked relevant data or misinterpreted the data, when conducting the data extraction and quality assessment. We tried to minimise this bias by having two researchers conducting the data extraction and quality assessment in order to obtain more accuracy and consistency, and authors were contacted for clarification, when needed.

Conclusions

There is no consensus on the measurements of fidelity in school-based obesity prevention programmes and the quality of methods used is weak. Therefore, researchers need to agree upon the operationalisation of concepts and clear reporting on methods employed to measure fidelity and increase the quality of fidelity measurements. Moreover, it is of importance to determine the relation between fidelity and programme outcomes to understand what level of fidelity is needed to ensure that programmes are effective. At last, more research is needed looking at the degree of implementation in real world settings. As such, researchers should not only focus on top-down measurements. In line with mutual adaptation approaches in intervention development and implementation, a bidirectional process should be part of process evaluations, wherein researchers examine whether and under which conditions adaptations to the programme have been made, whilst still being effective and sustainable in real world settings.

Abbreviations

- NA:

-

Not applicable

- SIRC:

-

Society for Implementation Research Collaboration

References

Wang Y, Cai L, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Weston C, Fawole O, et al. What childhood obesity prevention programmes work? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16(7):547–65.

Cleland V, McNeilly B, Crawford D, Ball K. Obesity prevention programs and policies: practitioner and policy maker perceptions of feasibility and effectiveness. Obesity. 2013;21(9):E448–E55.

Brown T, Summerbell C. Systematc review of school-based interventions that focus on changing dietary intake and physical activity levels to prevent childhood obesity: an update to the obesity guidance produced by the National Institute for health and clinical excellence. Obes Rev. 2009;10(1):110–41.

Khambalia AZ, Dickinson S, Hardy LL, Gill T, Baur LA. A synthesis of existing systematic reviews and meta-analysis of school-based behavioural interventions for controlling and preventing obesity. Obes Rev. 2012;13(3):214–33.

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327–50.

McGraw SA, Sellers DE, Johnson CC, Stone EJ, Bachman KJ, Bebchuk J, et al. Using process data to explain outcomes: an illustration from the child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (CATCH). Eval Rev. 1996;20(3):291–312.

Naylor PJ, Nettlefold L, Race D, Hoy C, Ashe MC, Higgins JW, et al. Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2015;72:95–115.

Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):67.

Windsor R. Evaluation of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Programs.: Oxford University Press 2015.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Bond L, Bonell C, Wen H, Moore L, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258.

Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):237–56.

Dane A, Schneider B. Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: are implementation effects out of control? Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18(1):23–45.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurements challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Blakely CH, Mayer JP, Gottschalk RG, Schmitt N, Davidson WS, Roitman DB, et al. The fidelity-adaptation debate: implications for the implementation of public sector social programs. Am J Community Psychol. 1987;15(3):253–68.

Elliott DS, Mihalic S. Issues in disseminating and replicating effective prevention programs. Prev Sci. 2004;5(1):47–53.

Reiser BJ, Spillane JP, Steinmuler F, Sorsa D, Carney K, Kyza E, editors. Investigating the mutual adaptation process in teachers’ design of technology-infused curricula. Fourth international conference of the learning sciences; 2013.

Hendriks A-M, Gubbels JS, De Vries NK, Seidell JC, Kremers SP, Jansen MW. Interventions to promote an integrated approach to public health problems: an application to childhood obesity. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012

Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2(1):40.

Linnan L, Steckler A. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass., editor; 2002.

Lambert J, Greaves C, Farrand P, Cross R, Haase A, Taylor A. Assessment of fidelity in individual level behaviour change interventions promoting physical activity among adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):765.

Steckler A, Ethelbah B, Martin CJ, Stewart D, Pardilla M, Gittelsohn J, et al. Pathways process evaluation results: a school-based prevention trial to promote healthful diet and physical activity in American Indian third, fourth, and fifth grade students. Prev Med. 2003;37(1):S80–90.

Wierenga D, Engbers LH, Van Empelen P, Duijts S, Hildebrandt VH, Van Mechelen W. What is acutually measured in process evaluations for worksite health promotion programs: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1190.

Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Aguiar EJ, Callister R. Randomized controlled trial of the physical activity leaders (PALs) program for adolescent boys from disadvantaged secondary schools. Prev Med. 2011;52(3–4):239–46.

Levine E, Olander C, Lefebvre C, Cusick P, Biesiadecki L, McGoldrick D. The team nutrition pilot study: lessons learned from implementing a comprehensive school-based intervention. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34(2):109–16.

Wind M, Bjelland M, Perez-Rodrigo C, Te Velde S, Hildonen C, Bere E, et al. Appreciation and implementation of a school-based intervention are associated with changes in fruit and vegetable intake in 10-to 13-year old schoolchildren—the pro children study. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(6):997–1007.

Ward DS, Saunders R, Felton G, Williams E, Epping J, Pate RR. Implementation of a school environment intervention to increase physical activity in high school girls. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(6):896–910.

Wang MC, Rauzon S, Studer N, Martin AC, Craig L, Merlo C, et al. Exposure to a comprehensive school intervention increases vegetable consumption. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(1):74–82.

van Nassau F, Singh AS, Hoekstra T, van Mechelen W, Brug J, Chinapaw MJ. Implemented or not implemented? Process evaluation of the school-based obesity prevention program DOiT and associations with program effectiveness. Health Educ Res. 2016;31(2):220–33.

Story M, Mays RW, Bishop DB, Perry CL, Taylor G, Smyth M, et al. 5-a-day power plus: process evaluation of a multicomponent elementary school program to increase fruit and vegetable consumption. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(2):187–200.

Singh A, Chinapaw M, Brug J, Van Mechelen W. Process evaluation of a school-based weight gain prevention program: the Dutch obesity intervention in teenagers (DOiT). Health Educ Res. 2009;24(5):772–7.

Sharma S, Helfman L, Albus K, Pomeroy M, Chuang R-J, Markham C. Feasibility and acceptability of brighter bites: a food co-op in schools to increase access, continuity and education of fruits and vegetables among low-income populations. J Prim Prev. 2015;36(4):281–6.

Shah S, van der Sluijs CP, Lagleva M, Pesle A, Lim K-S, Bittar H, et al. A partnership for health: working with schools to promote healthy lifestyle. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40(12):1011.

Saunders RP, Ward D, Felton GM, Dowda M, Pate RR. Examining the link between program implementation and behavior outcomes in the lifestyle education for activity program (LEAP). Eval Program Plann. 2006;29(4):352–64.

Salmon J, Jorna M, Hume C, Arundell L, Chahine N, Tienstra M, et al. A translational research intervention to reduce screen behaviours and promote physical activity among children: Switch-2-activity. Health Promot Int. 2010;26(3):311–21.

Salmon J, Ball K, Crawford D, Booth M, Telford A, Hume C, et al. Reducing sedentary behaviour and increasing physical activity among 10-year-old children: overview and process evaluation of the ‘switch-Play’intervention. Health Promot Int. 2005;20(1):7–17.

Robbins LB, Pfeiffer KA, Wesolek SM, Lo Y-J. Process evaluation for a school-based physical activity intervention for 6th-and 7th-grade boys: reach, dose, and fidelity. Eval Program Plann. 2014;42:21–31.

Robbins LB, Pfeiffer KA, Maier KS, LaDrig SM, Berg-Smith SM. Treatment fidelity of motivational interviewing delivered by a school nurse to increase girls' physical activity. J Sch Nurs. 2012;28(1):70–8.

Reinaerts E, De Nooijer J, De Vries NK. Fruit and vegetable distribution program versus a multicomponent program to increase fruit and vegetable consumption: which should be recommended for implementation? J Sch Health. 2007;77(10):679–86.

Prins RG, Brug J, van Empelen P, Oenema A. Effectiveness of YouRAction, an intervention to promote adolescent physical activity using personal and environmental feedback: a cluster RCT. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32682.

Naylor P-J, Macdonald HM, Zebedee JA, Reed KE, McKay HA. Lessons learned from action schools! BC—an ‘active school’model to promote physical activity in elementary schools. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9(5):413–23.

Naylor P, Scott J, Drummond J, Bridgewater L, McKay H, Panagiotopoulos C. Implementing a whole school physical activity and healthy eating model in rural and remote first nations schools: a process evaluation of action schools! BC. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(2):1296.

Nanney MS, Olaleye TM, Wang Q, Motyka E, Klund-Schubert J. A pilot study to expand the school breakfast program in one middle school. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(3):436–42.

Muckelbauer R, Libuda L, Clausen K, Kersting M. Long-term process evaluation of a school-based programme for overweight prevention. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35(6):851–7.

Martens M, van Assema P, Paulussen T, Schaalma H, Brug J. Krachtvoer: process evaluation of a Dutch programme for lower vocational schools to promote healthful diet. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(5):695–704.

Lehto R, Määttä S, Lehto E, Ray C, Te Velde S, Lien N, et al. The PRO GREENS intervention in Finnish schoolchildren–the degree of implementation affects both mediators and the intake of fruits and vegetables. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(7):1185–94.

Lee H, Contento IR, Koch P. Using a systematic conceptual model for a process evaluation of a middle school obesity risk-reduction nutrition curriculum intervention: choice, control & change. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(2):126–36.

Lederer AM, King MH, Sovinski D, Seo DC, Kim N. The relationship between school-level characteristics and implementation Fidelity of a coordinated school health childhood obesity prevention intervention. J Sch Health. 2015;85(1):8–16.

Larsen AL, Robertson T, Dunton G. RE-AIM analysis of a randomized school-based nutrition intervention among fourth-grade classrooms in California. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5(3):315–26.

King MH, Lederer AM, Sovinski D, Knoblock HM, Meade RK, Seo D-C, et al. Implementation and evaluation of the HEROES initiative: a tri-state coordinated school health program to reduce childhood obesity. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(3):395–405.

Jurg ME, Kremers SP, Candel MJ, Van der Wal MF, De Meij JS. A controlled trial of a school-based environmental intervention to improve physical activity in Dutch children: JUMP-in, kids in motion. Health Promot Int. 2006;21(4):320–30.

Jørgensen TS, Rasmussen M, Aarestrup AK, Ersbøll AK, Jørgensen SE, Goodman E, et al. The role of curriculum dose for the promotion of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents: results from the boost intervention. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):536.

Janssen M, Toussaint HM, van Mechelen W, Verhagen EA. Translating the PLAYgrounds program into practice: a process evaluation using the RE-AIM framework. J Sci Med Sport. 2013;16(3):211–6.

Jan S. Shape it up: a school-based education program to promote healthy eating and exercise developed by a health plan in collaboration with a college of pharmacy. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(5):403–13.

Hildebrand DA, Jacob T, Garrard-Foster D. Food and fun for everyone: a community nutrition education program for third-and fourth-grade students suitable for school wellness programs. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(1):93–5.

Heath EM, Coleman KJ. Evaluation of the institutionalization of the coordinated approach to child health (CATCH) in a US/Mexico border community. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(4):444–60.

Gray HL, Contento IR, Koch PA. Linking implementation process to intervention outcomes in a middle school obesity prevention curriculum,‘Choice, Control and Change’. Health Educ Res. 2015;30(2):248–61.

Gibson CA, Smith BK, DuBose KD, Greene JL, Bailey BW, Williams SL, et al. Physical activity across the curriculum: year one process evaluation results. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5(1):36.

Ezendam N, Noordegraaf V, Kroeze W, Brug J, Oenema A. Process evaluation of FATaintPHAT, a computer-tailored intervention to prevent excessive weight gain among Dutch adolescents. Health Promot Int. 2013;28(1):26–35.

Elinder LS, Heinemans N, Hagberg J, Quetel A-K, Hagströmer M. A participatory and capacity-building approach to healthy eating and physical activity–SCIP-school: a 2-year controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):145.

Dunton GF, Liao Y, Grana R, Lagloire R, Riggs N, Chou C-P, et al. State-wide dissemination of a school-based nutrition education programme: a RE-AIM (reach, efficacy, adoption, implementation, maintenance) analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(2):422–30.

Dunton GF, Lagloire R, Robertson T. Using the RE-AIM framework to evaluate the statewide dissemination of a school-based physical activity and nutrition curriculum:“exercise your options”. Am J Health Promot. 2009;23(4):229–32.

de Meij JS, van der Wal MF, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. A mixed methods process evaluation of the implementation of JUMP-in, a multilevel school-based intervention aimed at physical activity promotion. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(5):777–90.

Day ME, Strange KS, McKay HA, Naylor P-J. Action schools! BC–healthy eating: effects of a whole-school model to modifying eating behaviours of elementary school children. Can j Public Health. 2008;99(4):328–31.

Davis SM, Clay T, Smyth M, Gittelsohn J, Arviso V, Flint-Wagner H, et al. Pathways curriculum and family interventions to promote healthful eating and physical activity in American Indian schoolchildren. Prev Med. 2003;37(1):S24–34.

Davis M, Baranowski T, Resnicow K, Baranowski J, Doyle C, Smith M, et al. Gimme 5 fruit and vegetables for fun and health: process evaluation. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(2):167–76.

Dalton WT III, Schetzina K, Conway-Williams E. A coordinated school health approach to obesity prevention among Appalachian youth: middle school student outcomes from the winning with wellness project. Int J Health Sci Educ. 2014;2(1):2.

Christian MS, Evans CE, Ransley JK, Greenwood DC, Thomas JD, Cade JE. Process evaluation of a cluster randomised controlled trial of a school-based fruit and vegetable intervention: project tomato. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(3):459–65.

Campbell R, Rawlins E, Wells S, Kipping RR, Chittleborough CR, Peters TJ, et al. Intervention fidelity in a school-based diet and physical activity intervention in the UK: active for life year 5. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12(1):141.

Blom-Hoffman J, Kelleher C, Power TJ, Leff SS. Promoting healthy food consumption among young children: evaluation of a multi-component nutrition education program. J Sch Psychol. 2004;42(1):45–60.

Blom-Hoffman J. School-based promotion of fruit and vegetable consumption in multiculturally diverse, urban schools. Psychol Sch. 2008;45(1):16–27.

Bessems KM, van Assema P, Martens MK, Paulussen TG, Raaijmakers LG, de Vries NK. Appreciation and implementation of the Krachtvoer healthy diet promotion programme for 12-to 14-year-old students of prevocational schools. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):909.

Bessems KM, van Assema P, Crutzen R, Paulussen TG, de Vries NK. Examining the relationship between completeness of teachers’ implementation of the Krachtvoer healthy diet programme and changes in students’ dietary intakes. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(7):1273–80.

Bergh IH, Bjelland M, Grydeland M, Lien N, Andersen LF, Klepp K-I, et al. Mid-way and post-intervention effects on potential determinants of physical activity and sedentary behavior, results of the HEIA study-a multi-component school-based randomized trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):63.

Bere E, Veierød M, Bjelland M, Klepp K. Outcome and process evaluation of a Norwegian school-randomized fruit and vegetable intervention: fruits and vegetables make the marks (FVMM). Health Educ Res. 2005;21(2):258–67.

Barr-Anderson DJ, Laska MN, Veblen-Mortenson S, Farbakhsh K, Dudovitz B, Story M. A school-based, peer leadership physical activity intervention for 6th graders: feasibility and results of a pilot study. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(4):492–9.

Almas A, Islam M, Jafar TH. School-based physical activity programme in preadolescent girls (9–11 years): a feasibility trial in Karachi, Pakistan. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(7):515–9.

Aarestrup AK, Jørgensen TS, Jørgensen SE, Hoelscher DM, Due P, Krølner R. Implementation of strategies to increase adolescents’ access to fruit and vegetables at school: process evaluation findings from the boost study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):86.

Alaimo K, Carlson JJ, Pfeiffer KA, Eisenmann JC, Paek HJ, Betz HH, et al. Project FIT: a school, community and social marketing intervention improves healthy eating among low-income elementary school children. J Community Health. 2015;40(4):815–26.

Battjes-Fries MC, van Dongen EJ, Renes RJ, Meester HJ, Van't Veer P, Haveman-Nies A. Unravelling the effect of the Dutch school-based nutrition programme taste lessons: the role of dose, appreciation and interpersonal communication. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):737.

Blaine RE, Franckle RL, Ganter C, Falbe J, Giles C, Criss S, et al. Using school staff members to implement a childhood obesity prevention intervention in low-income school districts: the Massachusetts childhood obesity research demonstration (MA-CORD project), 2012-2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E03.

Burgermaster M, Gray HL, Tipton E, Contento I, Koch P. Testing an integrated model of program implementation: the food, Health & Choices School-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Intervention Process Evaluation. Prev Sci. 2017;18(1):71–82.

Dubuy V, De Cocker K, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Maes L, Seghers J, Lefevre J, et al. Evaluation of a real world intervention using professional football players to promote a healthy diet and physical activity in children and adolescents from a lower socio-economic background: a controlled pretest-posttest design. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):457.

Eather N, Morgan P, Lubans D. Improving health-related fitness in adolescents: the CrossFit TeensTM randomised controlled trial. J Sports Sci. 2016;34(3):209–23.

Hankonen N, Heino MT, Hynynen ST, Laine H, Araujo-Soares V, Sniehotta FF, et al. Randomised controlled feasibility study of a school-based multi-level intervention to increase physical activity and decrease sedentary behaviour among vocational school students. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):37.

Harris KJ, Richter KP, Schultz J, Johnston J. Formative, process, and intermediate outcome evaluation of a pilot school-based 5 a day for better health project. Am J Health Promot. 1998;12(6):378–81.

Griffin TL, Clarke JL, Lancashire ER, Pallan MJ, Adab P. Process evaluation results of a cluster randomised controlled childhood obesity prevention trial: the WAVES study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):681.

Jørgensen TS, Rasmussen M, Jorgensen SE, Ersboll AK, Pedersen TP, Aarestrup AK, et al. Curricular activities and change in determinants of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents: results from the boost intervention. Prevent Med Rep. 2017;5:48–56.

Lane H, Porter KJ, Hecht E, Harris P, Kraak V, Zoellner J. Kids SIP smartER: a feasibility study to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among middle school youth in central Appalachia. Am J Health Promot. 2017.https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117117715052.

Little MA, Riggs NR, Shin HS, Tate EB, Pentz MA. The effects of teacher fidelity of implementation of pathways to health on student outcomes. Eval Health Prof. 2015;38(1):21–41.

Reynolds KD, Franklin FA, Leviton LC, Maloy J, Harrington KF, Yaroch AL, et al. Methods, results, and lessons learned from process evaluation of the high 5 school-based nutrition intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(2):177–86.

Verloigne M, Ahrens W, De Henauw S, Verbestel V, Marild S, Pigeot I, et al. Process evaluation of the IDEFICS school intervention: putting the evaluation of the effect on children's objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in context. Obes Rev. 2015;16(2):89–102.

Naylor PJ, McKay HA, Valente M, Masse LC. A mixed-methods exploration of implementation of a comprehensive school healthy eating model one year after scale-up. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(5):924–34.

Perry CL, Sellers DE, Johnson C, Pedersen S, Bachman KJ, Parcel GS, et al. The child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (CATCH): intervention, implementation, and feasibility for elementary schools in the United States. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(6):716–35.

McKay HA, Macdonald HM, Nettlefold L, Masse LC, Day M, Naylor P-J. Action schools! BC implementation: from efficacy to effectiveness to scale-up. Br J Sports Med. 2014;49(4):210–8.

Chaudoir S, Dugan A, Barr C. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):22.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):53.

Thorpe K, Zwarenstein M, Oxman A, Treweek S, Furberg C, Altman D. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):464–75.

Lewis CC, Stanick CF, Martinez RG, Weiner BJ, Kim M, Barwick M, et al. The society for implementation research collaboration instrument review project: a methodology to promote rigorous evaluation. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):2.

Van Kann DH, Jansen M, De Vries S, De Vries N, Kremers S. Active living: development and quasi-experimental evaluation of a school-centered physical activity intervention for primary school children. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1315.

Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S, Finegood DT, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2602–4.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ken Snijders for his help in the literature search, data extraction and quality assessment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. RS: Performed the literature search, data extraction and quality assessment and wrote the article, KB: Initiated the study, supervised the study and was involved in writing the article. RO: Compiled the search strategy and provided feedback on the article. SK: Supervised the study and provided feedback on drafts of the article. FvN: Initiated the study, performed the literature search, data extraction and quality assessment and co-wrote the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA checklist. PRISMA checklist wherein we indicated in which part of the manuscript each item of the checklist was reported. (DOC 64 kb)

Additional file 2:

Search terms. Search strategy for various databases. (DOCX 29 kb)

Additional file 3:

Data extraction. Full overview of the data extraction of the included studies. (DOCX 84 kb)

Additional file 4:

Quality assessment. Full overview of the quality assessment of the fidelity components. (DOCX 48 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Schaap, R., Bessems, K., Otten, R. et al. Measuring implementation fidelity of school-based obesity prevention programmes: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 15, 75 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0709-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0709-x