Abstract

Background

As a source of readily available evidence, rigorously synthesized and interpreted by expert clinicians and methodologists, clinical guidelines are part of an evidence-based practice toolkit, which, transformed into practice recommendations, have the potential to improve both the process of care and patient outcomes. In Brazil, the process of development and updating of the clinical guidelines for the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS) is already well systematized by the Ministry of Health. However, the implementation process of those guidelines has not yet been discussed and well structured. Therefore, the first step of this project and the primary objective of this study was to summarize the evidence on the effectiveness of strategies used to promote clinical practice guideline implementation and dissemination.

Methods

This overview used systematic review methodology to locate and evaluate published systematic reviews regarding strategies for clinical practice guideline implementation and adhered to the PRISMA guidelines for systematic review (PRISMA).

Results

This overview identified 36 systematic reviews regarding 30 strategies targeting healthcare organizations, healthcare providers and patients to promote guideline implementation. The most reported interventions were educational materials, educational meetings, reminders, academic detailing and audit and feedback. Care pathways—single intervention, educational meeting—single intervention, organizational culture, and audit and feedback—both strategies implemented in combination with others—were strategies categorized as generally effective from the systematic reviews. In the meta-analyses, when used alone, organizational culture, educational intervention and reminders proved to be effective in promoting physicians' adherence to the guidelines. When used in conjunction with other strategies, organizational culture also proved to be effective. For patient-related outcomes, education intervention showed effective results for disease target results at a short and long term.

Conclusion

This overview provides a broad summary of the best evidence on guideline implementation. Even if the included literature highlights the various limitations related to the lack of standardization, the methodological quality of the studies, and especially the lack of conclusion about the superiority of one strategy over another, the summary of the results provided by this study provides information on strategies that have been most widely studied in the last few years and their effectiveness in the context in which they were applied. Therefore, this panorama can support strategy decision-making adequate for SUS and other health systems, seeking to positively impact on the appropriate use of guidelines, healthcare outcomes and the sustainability of the SUS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Clinical guidelines are defined as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances” [1]. As a source of readily available evidence, rigorously synthesized and interpreted by expert clinicians and methodologists, guidelines are part of an evidence-based practice toolkit which, transformed into practice recommendations, have the potential to improve both the process of care and patient outcomes [2]. For example, greater adherence to guidelines has been associated with reduced morbidity after appendectomy for complicated appendicitis, better and faster outcomes in patients with psychiatric disorders, better physical functioning outcomes, and less use of low back pain care [3,4,5].

However, although guidelines may be seen as important tools that support decision-making, in conjunction with clinical judgement and patient preference, there is still a lack of adherence to guidelines worldwide across different conditions and levels of care [6,7,8]. Studies from different countries have demonstrated suboptimal adherence to guidelines for low back pain in primary care, including the use of interventions with little or no benefit [9]. Among Australian nutritionists who provide clinical care to cancer patients, evidence indicates that only a third of the guidelines are routinely followed [10]. In Switzerland and Norway, a study found low overall adherence to current practice guidelines and high variation in the use of nutritional therapy in patients undergoing stem cell transplantation [11]. A study carried out in Norway showed low adherence of regular general practitioners to the palliative care guideline [12]. In the management of osteoarthritis, studies suggest that the main approaches recommended in the guidelines are underutilized and that the quality of care is inconsistent [13].

Numerous factors can influence the acceptance and use of guidelines, which may occur at the micro (individual behavioural, including clinicians and consumers), meso (organizational) or macro (context and system) level [14]. Some of these factors are intrinsic to the nature of newly recommended practice or technology itself, individual characteristics of healthcare professionals, and organizational capacity of health services to collect, adapt, share and apply evidence [15,16,17]. Other factors are intrinsic to guidelines; for example, when recommendations are not at all explicit, or they are distorted or ambiguous, due to conflict of interest, variable methodological quality, or being poorly written, they may be viewed as inapplicable to patients or as reducing clinician autonomy [18,19,20].

Thus, producing and providing high-quality guidelines is no guarantee that the recommendations will be implemented in healthcare practice, and therefore an active implementation strategy is necessary to encourage their uptake [21]. An iterative process consisting of several steps is recommended, including adapting guidelines to local context, identifying barriers to their use, selecting and implementing tailored interventions to promote guideline uptake, and monitoring and evaluating the associated outcomes and the sustainability of recommendations. Regardless of how guidelines are developed, what resources are required to support their implementation, or whether it is the responsibility of other individuals or organizations to implement them, detailed instructions for guideline implementation are needed [22, 23].

While the importance of turning knowledge into action and using available evidence to inform clinical practice is widely recognized, it still presents a challenge to most health services across different levels of government. In Brazil, the process of development and updating of the clinical guidelines for the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS) is already well systematized by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. However, the process for implementing those guidelines has not yet been discussed and well structured. Therefore, a partnership project to elaborate a validated framework for the implementation of clinical guidelines to be used within SUS is being developed by the Ministry of Health and Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. The first step of this project is to develop a review of the scientific literature with the aim of providing an overview of the strategies used to promote guideline implementation and their effectiveness [24].

Numerous systematic reviews have synthesized data from primary studies on the effectiveness of strategies for implementing guidelines in several clinical areas including mental health [25, 26], arthritis [27], asthma [28] and cardiovascular disease [29, 30]. With the growth in the publication of systematic reviews, the strategy of grouping data from reviews in a single study has become a useful means for providing ample evidence to decision-makers in the healthcare field [31]. In this sense, some initiatives have been carried out to systematize review data on the subject in question. Chan et al., for example, compiled data from systematic reviews on four specific strategies (reminders, educational outreach visits, audit and feedback, and provider incentives), and the study by Cheung et al. evaluated the reminders in changing professional behaviour in clinical settings [32, 33].

However, we did not find comprehensive studies in the global literature that synthesized this topic without restrictions to certain clinical areas and specific interventions. In this context, the primary objective of this study was to summarize the evidence on the effectiveness of different strategies used to promote clinical practice guideline implementation. This overview will provide a broad summary of the best evidence on guideline implementation to support strategy decision-making adequate for each context (national, regional, local levels) and clinical area, thus seeking to positively impact on healthcare outcomes and on the sustainability of the SUS.

Methods

This overview of systematic reviews was carried out in accordance with a protocol that was registered in the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews on 2 June 2017 (registration number: CRD42017065682). It was conducted following recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [34].

Inclusion criteria

Studies were selected based on the following criteria.

Types of studies

Systematic reviews that evaluated different strategies to promote clinical practice guideline implementation within a health system at the organizational, operational and individual levels (clinicians and patients) were included. Studies were selected regardless of the clinical area and focus of the intervention.

An overview of systematic reviews was considered the appropriate method to address this issue, as the literature search had identified relevant, recent systematic reviews with potential to cover a larger number of initiatives of clinical guideline implementation. Therefore, only systematic reviews were included.

Systematic review has been defined as “a review of a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise relevant studies, and to extract and analyse data from the studies included in the review” [35]. Considering this definition, studies with the following characteristics were classified as systematic reviews:

-

a clear research question;

-

eligibility criteria and description of the study selection process;

-

description of the time period, terms and databases used in the search.

Overviews of systematic reviews were not eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Participants were considered in relation to the level of clinical guideline implementation in health systems: at the macro-level (international, national), meso-level (regional, healthcare organizations), and micro-level (healthcare professionals or teams).

Types of interventions

Systematic reviews addressing any strategy for clinical practice guideline implementation were eligible for inclusion in this overview.

Comparator

No restrictions were applied to the comparator.

Outcomes

The following question guided the selection of studies:

-

1.

What is the effectiveness of strategies used to promote guideline implementation?

The primary outcomes of interest were strategies for clinical practice guideline implementation in a health system (organization, provider and patient levels).

Literature search

The literature search was conducted using the following electronic databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), the Cochrane Library, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, Health Systems Evidence, Rx for Change (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, CADTH) and Epistemonikos. The following databases were indicated in the overview protocol but they were not used: Guidelines International Network (GIN) website and International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) database, as well as Google and Google Scholar.

The basic search strategy combined search terms related to “clinical and therapeutic guidelines” (guidelines, clinical protocols, critical pathways, consensus and health planning guidelines) and “implementation of guidelines” (adherence, compliance, dissemination, accordance, concordance, adoption, barriers). The search strategies adapted for the electronic databases are presented in Additional file 1. The searches were carried out until 19 July 2017, and then updated until August 2019. There was no restriction on country, language or date of publication. Conference abstracts and studies that were not available in full text were excluded.

The terms were searched in the title and abstract, unless otherwise indicated in Additional file 1. The search results from the PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Scopus, Epistemonikos, Embase and CINAHL databases were imported into Covidence reference management software for study selection, and duplicates were removed. As for the results from the other databases, an Excel spreadsheet was used for the study selection process.

Screening and selection of studies

Titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies were screened by two independent reviewers (VP and FZ; update—VP and VC). Full-text assessment of potentially eligible studies was then independently undertaken for final selection. Disagreements regarding eligibility of studies were resolved by discussion and consensus, and when necessary, by a third reviewer. The screening process and results were reported according to the PRISMA statement.

Data extraction

Results from the included studies were systematically extracted by one reviewer (VP) according to the predefined protocol, and summarized in a table of evidence using a data collection template in Excel. A second reviewer checked the extracted data.

The following information was extracted: year; authors; title; objective; country; number of studies identified; characteristics of the target population; clinical area, type of outcome evaluated, strategies for clinical practice guideline implementation and their effectiveness; conclusion, limitations of the review, evidence gaps, source of funding for the study.

Data were extracted from selected systematic reviews and meta-analyses; however, when information from reviews was insufficient, the primary studies were consulted.

Methodological quality assessment

The methodological quality assessment using the AMSTAR 2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2) instrument [36] was conducted by two independent reviewers (VP and FZ; update—VP and VC). Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Data analysis

In the predefined protocol, data analysis was described only as a narrative synthesis. We subsequently refined this process even further. For systematic reviews, no meta-analysis of data was conducted. The results were reported as presented in the systematic reviews and meta-analyses. When the information was insufficient or unclear, we consulted the primary studies of each review. To do this, we recounted (i) all comparisons analysed in each study included in the review and (ii) the statistically positive results for each comparison studied. Each comparison was considered to be strategy A versus strategy B for each separate outcome (i.e. comparison of educational meeting effect associated with local opinion leader vs educational meeting only for outcome physician adherence). Based on the proportion of statistically positive results compared to the total analyses performed, efficacy was categorized as (1) generally effective (more than two thirds of the studies in a review showed positive effects), (2) mixed effects (one third to two thirds of the studies showed positive effects) or (3) generally ineffective (less than a third of the studies showed positive effects) [33]. In order to reduce bias in the interpretation of results obtained from a small number of evaluated comparisons, a cut-off was established of 10 or more comparisons evaluated to present the results of using the strategies.

Overlap analysis of studies included in each systematic review was performed to avoid duplication of effective results. In the case of duplication, we considered the results for the study included in the systematic review that presented more details regarding the strategy used to promote clinical practice guideline implementation. In cases of duplication of studies between systematic reviews selected from the first and second searches, we considered those included in systematic reviews from the first search.

Results

Selection of studies

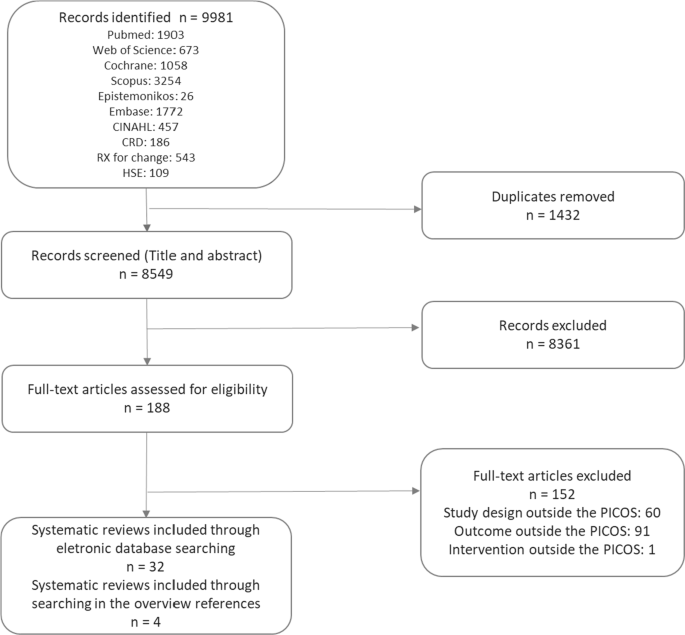

Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the process used to identify relevant systematic reviews that were included. In total, 9981 articles were identified, of which 189 were selected for full-text reading, and then 32 met all inclusion criteria. Four systematic reviews identified in the references of excluded overviews were also included. The excluded studies along with reasons for exclusion are shown in Additional file 2.

Characteristics of included studies

The systematic reviews included studies conducted in the following countries: United States (26 studies), United Kingdom (20 studies), Australia (14 studies), Netherlands (13 studies), Canada (12 studies), Germany (eight studies), France (six studies), Switzerland and Denmark (five studies each), Belgium, Thailand (four studies each), Iran, Brazil, Finland, Italy, Sweden, Norway (three studies each), Saudi Arabia, China, Singapore, New Zealand, Taiwan, Scotland, Spain, Mexico, Israel, Pakistan (two studies each), Ireland, Oceania, Argentina, Nepal, South Africa, Egypt, Oman, Japan, Korea, United Arab Emirates, Virgin Islands, South Africa, Georgia, Syria, China, Senegal, Mali, Benin, Malawi, Guatemala, India, Kenya and Zambia (one study each). There were also four studies conducted in a broader European setting (Table 1; Additional file 3).

The systematic reviews evaluated strategies for guideline implementation at various levels of health services, including inpatient and outpatient settings, primary and secondary care settings, private clinics, community health clinics, nursing homes, academic institutions, emergency services and intensive care units.

As for the clinical areas covered, four systematic reviews evaluated strategies for guideline implementation and dissemination related to physical and mental healthcare [25, 26, 37, 38], two related to cardiovascular diseases [29, 30, 39, 40], asthma [28, 41] and obstetrics [42, 43], and one related to stroke [44], physical therapy [45], pelvic inflammatory disease [46], osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis [27], pneumonia [47], pressure ulcers [48], intensive care units [49], prescription practices [50] and musculoskeletal disorders [51]. Some systematic reviews evaluated guidelines related to several clinical areas [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66].

The methodological quality of the included systematic reviews was assessed using the AMSTAR 2 tool [36], which consists of 16 items. According to this assessment, over the past decade, systematic reviews have provided more information on methods and parameters used in the analyses. One systematic review showed moderate, 12 low and 23 critically low methodological quality. The low rating was due to failure in meeting AMSTAR 2 criteria on the following critical domains: no justification for excluding individual studies (80%), no protocol registered before commencement of the review (75%) and no consideration of risk of bias when interpreting results from the review (47%) (Table 1; Additional file 3).

Strategies to promote clinical practice guideline implementation

The strategies reported in the systematic reviews were classified according to the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy of health interventions [67], and, when the strategy was not found in this taxonomy, we used the definition of systematic review of Grimshaw et al. [58]. Thirty strategies targeting healthcare organizations (n = 6), community (n = 1), health professionals (n = 21) and patients (n = 2) to promote guideline implementation were reported. Table 2 presents the strategies and their definitions.

Additionally, the strategies were classified according to the outcomes: process-, patient- and health professional-related outcomes, economic outcomes and nonspecific outcomes. In regard to single or multifaceted interventions, most outcomes were related to process, followed by patients and professionals. The most frequently reported strategies were educational materials, educational meetings, reminders, auditing and feedback, and academic detailing.

Effectiveness of the clinical practice guideline implementation strategies

Information on the effectiveness of clinical practice guideline implementation strategies was collected by considering the number of statistically significant positive results from each comparison analysed in the systematic reviews. The percentages of effective results in relation to the total analyses performed for each strategy were categorized as generally effective, mixed effects and generally ineffective. As described in “Methods”, we only present the results of strategies with 10 or more comparisons analysed (Table 3). The results of all strategies are presented in Additional file 4.

Most process-related outcomes evaluated how guideline implementation strategies affected requests for examinations, prescription of medications and performance of procedures, and whether they were in accordance with the guidelines. For these outcomes, 628 and 1814 analyses of strategies implemented alone and in combination with others, respectively, were carried out (Table 3).

In the case of single interventions, care pathway was the only generally effective categorized strategy. Reminders, educational meetings, audit feedback, local opinion leaders and practice support were classified as strategies yielding mixed effects. In the evaluation of multifaceted interventions, none reached the percentage of results to be categorized as generally effective (Table 3).

Health professional-related outcomes evaluated the changes in professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, self-reported practice and self-confidence in using, satisfaction in following, and willingness to follow guidelines. A small number of analyses were performed for these outcomes, 39 for strategies implemented alone and 150 for multifaceted interventions (Table 3).

Educational materials and educational meetings were the most commonly reported strategies when implemented alone, the latter being classified as generally effective, and the former as having mixed effects. In the evaluation of multifaceted interventions, changes in organizational culture and the audit and feedback strategy were classified as generally effective, while educational materials and educational meetings and reminders showed mixed results for the outcomes related to health professionals (Table 3).

Patient-related outcomes addressed clinical information, quality of life and patient satisfaction with care received. For these outcomes, 113 and 752 analyses of strategies implemented alone and in combination with others, respectively, were carried out. When used as single or multifaceted strategies, no intervention was considered generally effective (Table 3).

A small number of studies evaluated the effectiveness of guideline implementation strategies related to economic outcomes (eight analyses for single interventions, and 90 analyses for multifaceted interventions), none of which proved effective.

Two meta-analyses were included in this study. In total, eight strategies were evaluated for outcomes related to processes and patients [29, 30]. When used alone, organizational culture, educational intervention and reminders proved to be effective in promoting physicians' adherence to the guidelines [30]. In patient-directed interventions, patient education was effective, and promotion of patient self-management showed a statistically nonsignificant small benefit for this outcome [30]. Still focusing on physician adherence, when used in conjunction with other strategies (multifaceted strategies), organizational culture proved to be effective, education intervention showed mixed effects (one meta-analysis with effective results and one meta-analysis without statistical difference), and patient-directed reminders, educational meetings, academic detailing and information and communication technology presented results without statistical significance [29, 30] (Table 4).

For patient-related outcomes, educational intervention showed effective results for disease targets in the short and long term, and with no difference for mortality and hospitalization. The other strategies (audit and feedback, reminders, educational meetings, information and communication technology, and academic detailing) did not show positive statistical results [6]. It should be noted that educational interventions are extremely heterogeneous strategies without standardization of the elements that they comprise, and they may range from general instructions to digital education (Table 4).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to summarize the evidence on the effectiveness of different strategies used to promote clinical practice guideline implementation and dissemination. For this purpose, we synthesized the results of 36 systematic reviews on 30 strategies for guideline implementation. The scope of our study calls for caution in interpreting the effectiveness results, as no meta-analysis was performed, and the data were extracted from heterogeneous studies with different designs, clinical areas, contexts, intervention composition and outcomes. Thus, this data compilation can be useful as a map of the available evidence on guideline implementation strategies, on which clippings can be made according to the intended outcomes and the implementation context.

The strategies with the greatest volume of comparisons rated were educational materials, educational meetings, reminders, audit and feedback, and academic detailing. For outcomes related to processes assessed in systematic reviews, the only intervention categorized as generally effective when used alone was care pathways. Still, in the evaluation of these outcomes, the result of one of the included meta-analyses estimated that, when used alone, organizational culture, educational intervention, reminders and patient education were effective in promoting physicians' adherence to the guidelines. For multifaceted interventions, only organizational culture was effective.

Regarding the outcomes assessed in health professionals, educational meetings, used alone, and organizational culture and audit and feedback, both used in association with other strategies, were categorized as being generally effective with the data collected from systematic reviews. In evaluating the results of patients, systematic reviews did not present strategies categorized as generally effective; however, in one of the meta-analyses, educational interventions were effective for disease target results in the short and long term [29]. It should be noted that educational interventions are extremely heterogeneous strategies without standardization of the elements that they comprise, and they may range from general instructions to digital education. For economic outcomes, there was very limited evidence.

Overall, most interventions analysed had generally ineffective or mixed-effect outcomes. In the case of multifaceted strategies, it was not possible to define the contribution of each one and their specific attributes in the results, or to identify the synergistic effect of the interventions [68]. Our results were similar to those observed in the study by Grimshaw et al., in which the majority of evaluated strategies showed modest to moderate improvements in care. Grimshaw's systematic review was the most comprehensive identified, without restriction as to the type of strategy or clinical area. In that review, 235 studies were evaluated, with most having evaluated process measures as the primary outcome. The isolated interventions that were most commonly evaluated were reminders, dissemination of educational materials, and auditing and feedback. The authors concluded that there was an insufficient evidence base to point to strategies with the greatest potential to be effective in different contexts of guideline implementation [58].

In general, educational strategies have been widely addressed in the literature across a large number of studies, and regardless of whether they are the most effective strategy, they have presented important information to be targeted to specific groups [25, 52, 55, 63]. The small number of comparisons between educational interventions with more complex strategies involving large-scale changes and higher cost [55] results in evidence gaps, and in a tendency to value educational approaches that require fewer resources and are easier to adopt by guideline developers or implementers with limited funding [69], possibly obtaining moderate results that are unlikely to be contradicted by other study designs.

Results for educational meetings similar to ours were reported in a recent systematic review, in which it was observed that this strategy promoted modest improvement in professional practice and, to a lesser degree, in patient outcomes. Educational meetings can improve compliance with desired practice, and the results of using this strategy can be leveraged when used in conjunction with other approaches [70]. This result is corroborated by previous studies, where multifaceted educational interventions for knowledge translation seem to be more effective in improving professional practice outcomes [51], but not necessarily in improving treatment outcomes for patients [71, 72]. However, the heterogeneity of interventions described as educational strategies, presenting different teaching and learning methods, makes it difficult to conduct a more detailed comparison between each of the proposed interventions [52].

Reminders have also been considered low-cost and low-complexity approaches. Results in the literature have been modest but indicated that reminders can be effective in changing the behaviour of professionals [33, 73]. The use of reminders designed for specific needs may be more likely to succeed, and reminders that prompted or required professionals’ responses were more likely to be effective in changing behaviour [33]. In our overview, we did not indicate which features of the reminder systems could promote better results [73], but a simpler format, such as manual reminders delivered on paper, can show low and moderate results in behaviour change, and can be used as a single intervention to improve quality of service [74]. Literature on the use of electronic reminders applied to health professionals, such as pharmacists, to support practice change have presented controversial results, but studies with a more robust methodology may indicate greater efficacy in the community pharmacy setting [55].

Audit and feedback may be a relevant strategy to identify the coherence between the recommendation and what is practised by the healthcare providers. In an overview of systematic reviews, this strategy was generally effective in improving both the care process and clinical outcomes, although the authors did not consider the statistical significance of the results [32]. Providing continuous feedback to professionals is an important strategy to increase professionals’ awareness of the impact of their practice and manager support for decision-making [26]. An important literature review indicated that audit and feedback may be responsible for a small, but potentially important, benefit for professional practice, varying based on the way the intervention is designed and delivered. According to the analyses, feedback may be more effective when provided by a supervisor or senior colleague, delivered at least monthly, both verbally and in written format, and when it includes explicit targets and an action plan [75].

Two interventions that were relatively rarely addressed in the included systematic reviews, but with promising results, were care pathway and organizational culture. Care pathway is an intervention that involves the standardization of care processes and its implementation is usually complex, being more frequently used for diseases and high-cost situations [76]. In the case of our results, most of them came from studies in the cardiovascular area, which could support more comprehensive activities to implement guidelines in this clinical area. Organizational culture is also a more complex and costly intervention targeted at healthcare organizations. These interventions can be implemented by promoting, for example, revisions of local procedures, protocols and tasks [77].

Behaviour change of the team is another important factor to consider in the guideline implementation process. A pioneering study using psychological theory to identify barriers to implementation of clinical guidelines and evidence-based practice identified 12 different domains of behaviour change [78]. Therefore, when the literature review reveals many studies focusing on educational strategies—that is, only on the education domain—there is a lack of more complex studies to understand professional and organizational behaviour change, which could help to determine what strategies would be more effective in different circumstances [57]. Moreover, leadership presence and incentive policies [40], or even interventions targeting the entire multidisciplinary team, seem to be more commonly accepted in the strategies for guideline implementation and dissemination [60].

Once awareness of the critical points that can compromise the implementation of a clinical guideline has been established, targeted strategies can be used to overcome barriers. A literature review reported that interventions tailored to prospectively identified barriers are more likely to improve professional practice than no intervention or guideline dissemination. However, methods to identify barriers and adapt interventions to address these barriers need further improvement, and further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of tailored interventions in comparison with other interventions [79].

Adherence of both professionals and organizations to guidelines can be improved when they are developed locally or adapted to the local context, taking into account issues such as value judgements, use of resources, characteristics of the local context and feasibility [26]. In the implementation of very specific guidelines, analysis of local context may be even more relevant, and it can make a difference in, for example, prescription of medications (involving normative and structural issues), or conduct of specific services such as intensive care units [39, 49].

In view of the substantial heterogeneity among interventions and the wide range of areas and follow-ups to be studied, perhaps more important than a standard study is further research on a systematic analysis of context and a theoretical framework of implementation. Studies should explore the features of an intervention that are effective in a specific context and how this could be translated into another context [42]. It is worth mentioning that, in general, tailored implementation interventions should not be considered transferable between different conditions or countries [80].

A recent study described the process and results obtained with a project developed to identify barriers to the national childbirth guidelines in Brazil and strategies for implementation. After identifying and prioritizing barriers to implementation, a deliberative dialogue was undertaken to discuss options for addressing them based on an evidence synthesis. As a result, the following interventions were selected: promoting the use of multifaceted interventions, educational interventions, audit and feedback to adjust professional practice, and reminders to mediate the interaction between workers and service users; enabling patient-mediated interventions; and engaging opinion leaders to promote the use of guidelines [81]. In initiatives like this, the present study has the potential to provide an evidence map organized by intervention target, intended outcome and results achieved.

Strengths and limitations

The results presented in this overview were based on secondary data, and where necessary primary data was collected. Therefore, the first limitation is related to the lack of detailed information on the strategies and outcomes reported by the authors of the primary studies. Moreover, with regard to multifaceted interventions, some systematic reviews presented the main strategy without listing the other strategies used in combination with the main one.

Second, we used the EPOC taxonomy to classify the implementation interventions, but some systematic reviews, especially those prior to EPOC classification, had used their own categorization. In order to standardize the classification according to EPOC, we categorized some strategies based on data from the systematic reviews. In some cases, such reclassification may not entirely reflect the intervention addressed in the primary study, so this may have caused the results to appear more or less effective for each strategy.

Third, the wide scope and difficulty in gathering a large amount of information from different contexts in a comprehensible way should be taken into consideration, and the analysis of the results should consider this diversity (e.g. the level of development of the countries, types of services where strategies were implemented, clinical areas, attributes of each intervention). It should be mentioned that it was not our intention to conduct a meta-analysis of effectiveness data, but to present the strategies with a large number of analyses and a statistically significant impact on any of the outcomes evaluated.

The fourth limitation relates to the way that the results were tabulated to categorize the effectiveness of the strategies. The focus of the analysis was on positive results with statistical significance. However, many studies that assess guideline dissemination and implementation strategies are cluster-randomized controlled trials, which present unit-of-analysis errors that make it difficult to make precise estimates regarding the statistical significance of the strategies [82].

Conclusion

Generally, national clinical guideline developers are not responsible for implementation and may leave it to regional or local groups. However, guideline implementation may require a national approach that provides a basis for effective use at the local level. The data presented in this overview can serve as an important source of information, while more robust evidence may establish a coherent relationship between professional and organizational behaviour to better inform the choice of interventions, and to evaluate the efficiency of dissemination and implementation strategies in the presence of different barriers and facilitators.

Further research is needed to compare more complex implementation strategies, as simple strategies reported with good results in the literature can be used in early interventions. The decision-making of managers should be based on the whole context of the health service, the evidence available so far, and the best use of resources. Sometimes the implementation of a guideline can be justified in a specific field or area, but it is important to take scarce resources into consideration when prioritizing actions and strategies that may contribute to improve practices in health services.

Therefore, the identification and assessment of the main factors related to the guideline implementation process and the discussion of the strategies addressed in this overview are relevant in facilitating the direction and decision-making of guideline implementers. Even if the included literature is unanimous in highlighting the various limitations related to the lack of standardization, low methodological quality of the studies, and especially the lack of conclusions about the superiority of one strategy over another [26, 54, 58], the summary of the results of this overview provides information on the strategies that have been most widely studied in the last few years and their effectiveness in the context in which they were applied. The identification of barriers, facilitators, perspectives of behaviour change and context, combined with the results from the best available evidence, can be an important tool for guideline implementation.

Thus, this panorama can support strategy decision-making adequate for the SUS and other health systems, seeking to positively impact on the appropriate use of guidelines, healthcare outcomes and the sustainability of the SUS.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Browman GP, Levine MN, Mohide EA, Hayward RS, Pritchard KI, Gafni A, et al. The practice guidelines development cycle: a conceptual tool for practice guidelines development and implementation. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(2):502–12.

Zimlichman E, Meilik-Weiss A. Clinical guidelines as a tool for ensuring good clinical practice. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004;6(10):626–7.

Setkowski K, Boogert K, Hoogendoorn AW, Gilissen R, van Balkom AJLM. Guidelines improve patient outcomes in specialised mental health care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand [Internet]. 2021;144(3):246–58.

Wakeman D, Livingston MH, Levatino E, Juviler P, Gleason C, Tesini B, et al. Reduction of surgical site infections in pediatric patients with complicated appendicitis: utilization of antibiotic stewardship principles and quality improvement methodology. J Pediatr Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.09.031.

McGuirk B, King W, Govind J, Lowry J, Bogduk N. Safety, efficacy, and cost effectiveness of evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute low back pain in primary care. Spine [Internet]. 2001;26(23):2615–22.

van de Klundert J, Gorissen P, Zeemering S. Measuring clinical pathway adherence. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43(6):861–72.

Milchak JL, Carter BL, James PA, Ardery G. Measuring adherence to practice guidelines for the management of hypertension: an evaluation of the literature. Hypertension. 2004;44(5):602–8.

Roberts VI, Esler CN, Harper WM. What impact have NICE guidelines had on the trends of hip arthroplasty since their publication? The results from the Trent Regional Arthroplasty Study between 1990 and 2005. J Bone Jt Surg Br Vol. 2007;89(7):864–7.

Slade SC, Kent P, Patel S, Bucknall T, Buchbinder R. Barriers to primary care clinician adherence to clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(9):800–16.

Edwards A, Baldwin N, Findlay M, Brown T, Bauer J. Evaluation of the agreement, adoption, and adherence to the evidence-based guidelines for the nutritional management of adult patients with head and neck cancer among Australian dietitians. Nutr Diet. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/1747-0080.12702.

Baumgartner A, Bargetzi M, Bargetzi A, Zueger N, Medinger M, Passweg J, et al. Nutritional support practices in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation centers: a nationwide comparison. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif). 2017;35:43–50.

Fasting A, Hetlevik I, Mjølstad BP. Palliative care in general practice; a questionnaire study on the GPs role and guideline implementation in Norway. BMC Fam Pract. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01426-8.

Swaithes L, Paskins Z, Dziedzic K, Finney A. Factors influencing the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for osteoarthritis in primary care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Musculoskelet Care. 2020;18(2):101–10.

Smith T, McNeil K, Mitchell R, Boyle B, Ries N. A study of macro-, meso- and micro-barriers and enablers affecting extended scopes of practice: the case of rural nurse practitioners in Australia. BMC Nurs. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0337-z.

Baiardini I, Braido F, Bonini M, Compalati E, Canonica GW. Why do doctors and patients not follow guidelines? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:228–33.

Kilsdonk E, Peute LW, Jaspers MWM. Factors influencing implementation success of guideline-based clinical decision support systems: a systematic review and gaps analysis. Int J Med Inform. 2017;98:56–64.

Francke AL, Smit MC, de Veer AJE, Mistiaen P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8(1):38.

Netsch DS, Kluesner JA. Critical appraisal of clinical guidelines. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2010;37(5):470–3.

Lenzer J. Why we can’t trust clinical guidelines. BMJ (Online). 2013. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3830.

Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 1997;157(4):408–16.

Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID. Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell/BMJ; 2009. p. 1–318.

Abbasi K. Knowledge, lost in translation. J R Soc Med. 2011;104(12):487.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24.

Brasil. Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. Projeto Apoio ao aprimoramento da gestão de tecnologias no SUS: plataforma de tradução, intercâmbio e apropriação social do conhecimento / Relatório do subprojeto iGUIAS. 2020. https://brasilia.fiocruz.br/aagts/guias-de-implementacao-iguias/.

Docherty M, Shaw K, Goulding L, Parke H, Eassom E, Ali F, et al. Evidence-based guideline implementation in low and middle income countries: lessons for mental health care. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2017;11(1):8.

Bighelli I, Ostuzzi G, Girlanda F, Cipriani A, Becker T, Koesters M, et al. Implementation of treatment guidelines for specialist mental health care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12(12): 009780.

Lineker SC, Husted JA. Educational interventions for implementation of arthritis clinical practice guidelines in primary care: effects on health professional behavior. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(8):1562–9.

Okelo SO, Butz AM, Sharma R, Diette GB, Pitts SI, King TM, et al. Interventions to modify health care provider adherence to asthma guidelines: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):517–34.

Jeffery RA, To MJ, Hayduk-Costa G, Cameron A, Taylor C, Van Zoost C, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to cardiovascular disease guidelines: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:174.

Unverzagt S, Oemler M, Braun K, Klement A. Strategies for guideline implementation in primary care focusing on patients with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31(3):247–66.

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132–40.

Chan WV, Pearson TA, Bennett GC, Cushman WC, Gaziano TA, Gorman PN, et al. ACC/AHA special report: clinical practice guideline implementation strategies: a summary of systematic reviews by the NHLBI implementation science work group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(8PG-1076–1092):1076–92.

Cheung A, Weir M, Mayhew A, Kozloff N, Brown K, Grimshaw J. Overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of reminders in improving healthcare professional behavior. Syst Rev. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-36.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097.

Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Version 5. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Online). 2017;358: j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008.

Weinmann S, Koesters M, Becker T. Effects of implementation of psychiatric guidelines on provider performance and patient outcome: systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115(6):420–33.

Bauer MS. A review of quantitative studies of adherence to mental health clinical practice guidelines. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002;10(3):138–53.

Nguyen T, Nguyen HQ, Widyakusuma NN, Nguyen TH, Pham TT, Taxis K. Enhancing prescribing of guideline-recommended medications for ischaemic heart diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions targeted at healthcare professionals. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1): e018271.

Shanbhag D, Graham ID, Harlos K, Haynes RB, Gabizon I, Connolly SJ, et al. Effectiveness of implementation interventions in improving physician adherence to guideline recommendations in heart failure: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e017765–e017765.

Dexheimer JW, Borycki EM, Chiu K-W, Johnson KB, Aronsky D. A systematic review of the implementation and impact of asthma protocols. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:82.

Imamura M, Kanguru L, Penfold S, Stokes T, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Shaw B, et al. A systematic review of implementation strategies to deliver guidelines on obstetric care practice in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstetr. 2017;136(1):19–28.

Chaillet N, Dubé E, Dugas M, Audibert F, Tourigny C, Fraser WD, et al. Evidence-based strategies for implementing guidelines in obstetrics: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1234–45.

Donnellan C, Sweetman S, Shelley E. Health professionals’ adherence to stroke clinical guidelines: a review of the literature. Health Policy. 2013;111(3):245–63.

van der Wees PJ, Jamtvedt G, Rebbeck T, de Bie RA, Dekker J, Hendriks EJM. Multifaceted strategies may increase implementation of physiotherapy clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54(4):233–41.

Liu B, Donovan B, Hocking JS, Knox J, Silver B, Guy R. Improving adherence to guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pelvic inflammatory disease: a systematic review. Infect Dis Obstetr Gynecol. 2012;2012: 325108.

Cortoos PJ, Simoens S, Peetermans W, Willems L, Laekeman G. Implementing a hospital guideline on pneumonia: a semi-quantitative review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):358–67.

Tooher R, Middleton P, Babidge W. Implementation of pressure ulcer guidelines: what constitutes a successful strategy? J Wound Care. 2003;12(10):373–82.

Jordan P, Mpasa F, ten Ham-Baloyi W, Bowers C. Implementation strategies for guidelines at ICUs: a systematic review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2017;30(4):358–72.

Gross PA, Pujat D. Implementing practice guidelines for appropriate antimicrobial usage: a systematic review. Med Care. 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):II55-69.

Al Zoubi FM, Menon A, Mayo NE, Bussières AE. The effectiveness of interventions designed to increase the uptake of clinical practice guidelines and best practices among musculoskeletal professionals: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):435.

Häggman-Laitila A, Mattila LR, Melender HL. A systematic review of the outcomes of educational interventions relevant to nurses with simultaneous strategies for guideline implementation. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(3–4):320–40.

Diehl H, Graverholt B, Espehaug B, Lund H. Implementing guidelines in nursing homes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:298.

Flodgren G, Hall AM, Goulding L, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Leng GC, et al. Tools developed and disseminated by guideline producers to promote the uptake of their guidelines. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8: CD10669.

Watkins K, Wood H, Schneider CR, Clifford R. Effectiveness of implementation strategies for clinical guidelines to community pharmacy: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2015;10:151.

Brusamento S, Legido-Quigley H, Panteli D, Turk E, Knai C, Saliba V, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of strategies to implement clinical guidelines for the management of chronic diseases at primary care level in EU Member States: a systematic review. Health Policy. 2012;107(2–3):168–83.

Hakkennes S, Dodd K. Guideline implementation in allied health professions: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(4):296–300.

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(6):1–72.

Thomas LH, McColl E, Cullum N, Rousseau N, Soutter J, Steen N. Effect of clinical guidelines in nursing, midwifery, and the therapies: a systematic review of evaluations. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(4):183–91.

Medves J, Godfrey C, Turner C, Paterson M, Harrison M, MacKenzie L, Durando P. Systematic review of practice guideline dissemination and implementation strategies for healthcare teams and team-based practice. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2010;8(2):79–89.

de Angelis G, Davies B, King J, McEwan J, Cavallo S, Loew L, et al. Information and communication technologies for the dissemination of clinical practice guidelines to health professionals: a systematic review. JMIR Med Educ. 2016;2(2): e16.

Wensing M, van der Weijden T, Grol R. Implementing guidelines and innovations in general practice: which interventions are effective? Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48(427):991–7.

Tudor Car L, Soong A, Kyaw BM, Chua KL, Low-Beer N, Majeed A. Health professions digital education on clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review by Digital Health Education collaboration. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):139.

Heselmans A, van de Velde S, Donceel P, Aertgeerts B, Ramaekers D. Effectiveness of electronic guideline-based implementation systems in ambulatory care settings—a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2009;4:82.

Liang L, Bernhardsson S, Vernooij RWM, Armstrong MJ, Bussières A, Brouwers MC, et al. Use of theory to plan or evaluate guideline implementation among physicians: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0557-0.

Damiani G, Pinnarelli L, Colosimo SC, Almiento R, Sicuro L, Galasso R, et al. The effectiveness of computerized clinical guidelines in the process of care: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:2.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). The EPOC taxonomy of health systems interventions. Oslo; 2016. http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors. Accessed 14 Jan 2019.

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39(8 SUPPL. 2 PG-2–45):II2-45.

Forsetlund L, Bjørndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O’Brien MA, Wolf F, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2.

Forsetlund L, O’Brien MA, Forsén L, Reinar LM, Okwen MP, Horsley T, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;9(9).

Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Brennan GP, Magel J. Does continuing education improve physical therapists’ effectiveness in treating neck pain? A randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2009;89(1):38–47.

Chipchase LS, Cavaleri R, Jull G. Can a professional development workshop with follow-up alter practitioner behaviour and outcomes for neck pain patients? A randomised controlled trial. Man Ther. 2016;25:87–93.

Shojania KG, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009(3): CD001096.

Pantoja T, Grimshaw JM, Colomer N, Castañon C, Leniz MJ. Manually-generated reminders delivered on paper: effects on professional practice and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12(12): CD001174.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young J, Odgaard-Jensen J, French S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online). 2012;6: CD000259.

Payedimarri AB, Ratti M, Rescinito R, Vasile A, Seys D, Dumas H, et al. Development of a model care pathway for Myasthenia Gravis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11591.

Haggman-Laitila A, Mattila LR, Melender HL. A systematic review of the outcomes of educational interventions relevant to nurses with simultaneous strategies for guideline implementation. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(3–4 PG-320–340):320–40.

Grimshaw J. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for evaluating guideline implementation strategies. Fam Pract. 2000;17(Suppl 1):S11–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/17.suppl_1.s11.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, Robertson N. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3: CD005470.

Krause J, Van Lieshout J, Klomp R, Huntink E, Aakhus E, Flottorp S, et al. Identifying determinants of care for tailoring implementation in chronic diseases: an evaluation of different methods. Implement Sci. 2014;9:102.

Barreto JOM, Bortoli MC, Luquine CD Jr, Oliveira CF, Toma TS, et al. Implementation of national childbirth guidelines in Brazil: barriers and strategies. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:1.

Campbell MK, Mollison J, Steen N, Grimshaw JM, Eccles M. Analysis of cluster randomized trials in primary care: a practical approach. Fam Pract. 2000;17(2):192–6.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank M. Sharmila A. Sousa, Mabel F. Figueiró, Kássia Fernandes, Everton N. da Silva and Marcus T. Silva.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Health of Brazil (TED-MS-FIOCRUZ #43/2016). The funder had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, or writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VP and JB designed the study. VP, VC and FZ collected the data. VP analysed the data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. SN and JB reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

There was no need for the ethical approval as the study relied on documents available in the public domain.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Literature search.

Additional file 2.

Excluded studies.

Additional file 3.

Characteristics and AMSTAR2 of the systematic reviews.

Additional file 4.

Effectiveness of guideline implementation strategies from systematic reviews by type of outcome.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pereira, V.C., Silva, S.N., Carvalho, V.K.S. et al. Strategies for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in public health: an overview of systematic reviews. Health Res Policy Sys 20, 13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00815-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00815-4