Abstract

Background

This is the sixth of our 11-paper supplement entitled “Community Health Workers at the Dawn of New Era”. Expectations of community health workers (CHWs) have expanded in recent years to encompass a wider array of services to numerous subpopulations, engage communities to collaborate with and to assist health systems in responding to complex and sometimes intensive threats. In this paper, we explore a set of key considerations for training of CHWs in response to their enhanced and changing roles and provide actionable recommendations based on current evidence and case examples for health systems leaders and other stakeholders to utilize.

Methods

We carried out a focused review of relevant literature. This review included particular attention to a 2014 book chapter on training of CHWs for large-scale programmes, a systematic review of reviews about CHWs, the 2018 WHO guideline for CHWs, and a 2020 compendium of 29 national CHW programmes. We summarized the findings of this latter work as they pertain to training. We incorporated the approach to training used by two exemplary national CHW programmes: for health extension workers in Ethiopia and shasthya shebikas in Bangladesh. Finally, we incorporated the extensive personal experiences of all the authors regarding issues in the training of CHWs.

Results

The paper explores three key themes: (1) professionalism, (2) quality and performance, and (3) scaling up. Professionalism: CHW tasks are expanding. As more CHWs become professionalized and highly skilled, there will still be a need for neighbourhood-level voluntary CHWs with a limited scope of work. Quality and performance: Training approaches covering relevant content and engaging CHWs with other related cadres are key to setting CHWs up to be well prepared. Strategies that have been recently integrated into training include technological tools and provision of additional knowledge; other strategies emphasize the ongoing value of long-standing approaches such as regular home visitation. Scale-up: Scaling up entails reaching more people and/or adding more complexity and quality to a programme serving a defined population. When CHW programmes expand, many aspects of health systems and the roles of other cadres of workers will need to adapt, due to task shifting and task sharing by CHWs.

Conclusion

Going forward, if CHW programmes are to reach their full potential, ongoing, up-to-date, professionalized training for CHWs that is integrated with training of other cadres and that is responsive to continued changes and emerging needs will be essential. Professionalized training will require ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the quality of training, continual updating of pre-service training, and ongoing in-service training—not only for the CHWs themselves but also for those with whom CHWs work, including communities, CHW supervisors, and other cadres of health professionals. Strong leadership, adequate funding, and attention to the needs of each cadre of CHWs can make this possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The roles of CHWs have changed substantially over recent decades as the services they provide and the specific groups that they have commonly focused on—historically, mostly children and women of childbearing age—have also expanded. CHW responsibilities now may also include newborns, subpopulations with other infectious diseases, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), and mental health as well as other services such as registration of vital events, disease surveillance, and response to humanitarian disasters and pandemics (including COVID-19) [1,2,3,4]. CHW programmes have seen a gradual shift from comprising mostly lay workers providing health promotion and education and linking communities to services offered by other health professionals, to becoming first-line providers for many services. These may include provision of immunizations, injectable contraceptives, vitamin A supplementation, and deworming medicine; diagnosis and treatment of childhood pneumonia, diarrhoea, and undernutrition using protocols for integrated community case management (iCCM); the provision of commodities including contraceptives and insecticide-treated bed nets; the detection and treatment of tuberculosis (TB) patients; and working in a range of vertical programmes such as those to control HIV and malaria [5,6,7]. Many CHW programmes have also improved maternal and child health through their support for antenatal care, safe delivery, postnatal care, and home-based care of the newborn [8,9,10]. The roles that CHWs are currently providing in large-scale CHW programmes is discussed further in Paper 5 in this series on roles and tasks [11].

In recent years, health systems are increasingly facing epidemiological and demographic transitions and also crises such as climate change, conflict, and outbreaks like the current COVID-19 pandemic. This is pressuring health system leaders to look for strategies to respond to these complex and often long-term care needs of their populations [12,13,14]. While much of the health systems strengthening literature does not explicitly identify community or CHW roles [15], CHWs are providing an increasing range of care, managing more complex health issues, collaborating more closely with other health workers, and helping to better link communities with health systems as part of a better integrated health system [16, 17].

All of these shifts have direct influences on the selection criteria and the duration, content, and modalities of pre-service and in-service training for CHWs. Training has been identified as an important factor for CHW programme successes as well as a barrier when not adequately provided. While very important, the broader literature on training of health workers in low- and middle-income countries [18, 19] suggests that training CHWs in isolation from the context in which they work is not likely to improve their performance, and even if combined with supervision and group problem-solving approaches, their effects on provider quality of care may not be as significant as might be expected.

The recent WHO guideline on health policy and system support for CHW programmes break out guidance on selection criteria, duration of pre-service training, competencies for curriculum, modalities of training, and certification [20]. While all of the recommendations are conditional on the specific programme context and objectives, it is clear from the guideline that decisions related to the kind and extent of CHW training must reflect the kinds of roles and tasks they will perform, which in many contexts, are becoming more extensive and more highly integrated into the health system [21].

Recognizing the recent renewed interest in CHW programmes in light of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the goal of achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) by 2030, there is intensified attention on how to optimize and scale these programmes [22, 23]. This paper aims to provide actionable guidance for practitioners and researchers, based on the current literature and our experiences, regarding training related to CHW programmes in the years ahead. This is the sixth paper of an 11-paper series [11, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] concerning the growing importance of CHW programmes and their potential significance for contributing to an acceleration of progress in achieving global health goals.

This paper builds on Chapter 9, “Training Community Health Workers for Large-Scale Community-Based Health Care Programs”, written by one of us (IA) in the 2014 publication entitled Developing and Strengthening Community Health Worker Programs at Scale: A Reference Guide for Program Managers and Policy Makers [33] (which we refer to as the CHW Reference Guide). That chapter synthesized extensive evidence to date and laid out several takeaway messages: (1) tailor the training to the context as well as to the ongoing needs of individual CHWs rather than design “one-size-fits-all” trainings; (2) learn from and build on what is working, (3) draw from examples of diverse exemplary cases of how training has been accomplished; and (4) ensure a comprehensive training package that integrates pre-service training with in-service training of CHWs, training of supervisors of CHWs, training of communities for their roles, and training of others in the health system about CHWs (the roles and responsibilities of CHWs) and their value to the health system.

Here, we update the contents of that 2014 chapter to provide a summary of the current status of training CHWs in order to understand the new status quo. Also, we identify a set of current priorities for additional actions and research related to training CHWs—and other workers involved in supporting primary healthcare (PHC) and community health programmes such as supervisors, clinicians, and managers—based on current evidence regarding the approaches to training now being utilized by national CHW programmes throughout the world [34]. Finally, we consider training from a broader perspective as well—not only the training needs of CHWs but the training needs for all those involved with the CHW programme—in order to sustainably enhance the quality and performance of the entire programme. We utilize case examples and current literature to explore the opportunities and challenges that each priority issue presents.

Methods

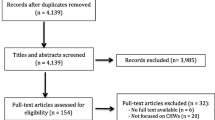

As mentioned above, we updated and expanded a chapter from a previous book on training of CHWs in large-scale programmes [35]. We explored the limited existing peer-reviewed literature as well as grey literature pertaining the recruitment and training of CHWs. We also relied on the extensive personal experience of the authors related to training of CHWs along with their wide knowledge of this topic as a result of long-standing work in this area. We reviewed the systematic review of reviews concerning CHWs to ascertain publications related to the training of CHWs [4, 36]. We reviewed the 2018 WHO Guideline for CHW programmes to include their recommendations regarding training [37]. Most importantly, we relied on recently published information from a recently published compendium of 29 national CHW programmes entitled Health for the People: National Community Health Programs from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe [21]. All of the case studies followed the same format in terms of topics addressed, and one of those topics is “selection and training”. To our knowledge, this is the most detailed current information about national CHW programmes that is available at present.

Results

Current status of training in national CHW programmes around the world

A recently published compendium of 29 case studies (including one example of a failed national CHW programme) provides an array of experiences regarding training CHWs themselves (Table 1). The duration, modalities, and main content varies widely, from just a few days or weeks up to as much as 3 years (for Nigeria’s community health extension workers [CHEWs]). In Paper 1 of this series [24], we classify CHWs into three categories: community health volunteers (CHVs), health extension workers (HEWs), and auxiliary health workers. CHVs have only a few days of training and may receive some intermittent per diem payments or other forms of limited remuneration and/or other informal incentives such as recognition and respect from their community. Higher-level CHWs are more extensively trained and may receive a regular salary. We have delineated our discussion of priority issues and opportunities by these categories of CHWs where appropriate.

Training of other health workers to more effectively engage and collaborate with and support CHWs has been limited, with many programmes providing no explicit training and or support to other cadres [38]. While issues and challenges related to supervising CHWs (both for clinicians and managers who supervise CHWs as well as for CHWs who supervise other CHWs) have been explored in South Africa, Tanzania, and other contexts [39, 40], there is limited documentation in the academic literature of any training programmes or similar support services that have been developed and utilized to prepare and support supervisors in these important roles [41]. Technology has also been held up as a solution to CHW supervision challenges—some of which it can alleviate, such as timely communication and access to current information [42,43,44]—but it is not a replacement for key relational aspects that are critical to CHW motivation and effectiveness, including valuing their unique contributions and establishing appropriate incentive structures. (See Paper 7 on supervision [28] and Paper 8 on motivation [29] in this series for further discussion of these issues.)

Training-related priorities for the future of CHW programme scale and sustainability

This section is organized around a set of priority considerations related to training for CHW programmes going forward. We have organized these around three overall themes: (1) professionalization, (2) quality and performance, and (3) scale-up. We will describe each and provide some background on the experience to date and examples for each one, and then describe some challenges and opportunities that can help CHW programmes navigate each going forward.

Implications of the recent professionalization of training for CHWs

Over time, the engagement of health systems with communities has increased [45,46,47]. Communities expect a more professionalized and capable health system, including professionalized CHWs [48,49,50]. Professionalization entails the processes, including for CHWs, whereby an occupation becomes established as a recognized line of work, with formal entry-level training and established remuneration. CHWs and health systems have been evolving to meet this demand by expanding training programmes, establishing standards, improving remuneration, and ensuring that CHWs are recognized by communities and other professionals in the health systems [51]. Two major pressures driving professionalization are rising expectations by communities for (1) a trained healthcare worker to be available on a full-time basis to provide clinical services and advice at the community level and (2) referral to and counter-referral from higher-level healthcare services [52]. Generally, the shifts in roles have included expansion of services to include prevention and treatment of NCDs, mental health, data management and disease surveillance, as well as expanded clinical care roles; further details about the changes in CHW roles were described earlier in the Context section as well.

At the same time, socioeconomic inequities persist and are even increasing regarding who can afford what kinds of care [53]. All of this means that CHWs require additional training in order to provide the level and complexity of clinical care and authoritative guidance and coordination to navigate the rest of the health system that is needed to support improved health status at the community level—particularly for remote and underserved populations—and to meet community expectations [53,54,55]. Numerous factors, such as distance, lack of money for transport, and medical fees, are clearly demarcating sections of the community who do not have access to health facility-based care [56,57,58]. The inability of some people to travel to a facility for essential services has led to further task sharing and shifting to CHWs in some countries, though not all.

Pressures on CHWs are compounded by the continued shortage of other key cadres of PHC workers, including nurses and primary care physicians in many contexts, particularly in rural and disenfranchised populations [9, 59,60,61,62,63,64]. In addition to social and cultural drivers of shifts in the roles and expectations of CHWs, changing healthcare needs of populations caused by ongoing demographic and epidemiologic transitions are also driving the burden of disease and what is needed to sustain and improve the health of communities [65, 66]. Further, CHWs also need to be considered as full partners and as adult learners, and they need to have a role in designing and engaging in their training experiences in order to have strong ownership of their roles and carry forward with their essential services, even during times of transition and challenge in the systems where they work. Health systems must evolve, and therefore so must the package of health services that CHWs are expected to provide. Of course, these services are often organized in collaboration with other providers, and some countries are also seeking to expand the number of workers in other cadres of workers such as doctors and nurses. As new priorities arise, such as NCDs, mental health, and newborn care, stronger PHC teams that include a formal role for CHWs that are able to provide valued services directly to communities and can also employ referral strategies are needed [67,68,69]. New services and protocols will need to be added to packages of essential services provided by CHWs at the household level, and trainings will be needed to conduct this work effectively.

Increasingly, health programmes are training and using higher-level CHWs. Some of these CHWs have a significant community engagement focus (such as the HEWs in Ethiopia), while others (such as the CHCPs in Bangladesh) spend most or all of their time based at a health post. Even in instances where health systems rely on volunteer CHVs to promote healthy behaviours and to link their communities with the health system, these volunteers often include more highly educated youth who are seeking professional opportunities to secure more stable and better-paying work as their careers progress [52].

As more highly educated CHWs are recruited and are trained more extensively, new challenges will arise. For instance, it may become more difficult to recruit CHWs from the communities they will service, and it may also become more difficult to retain them there [70]. As training durations increase, CHWs will need to invest more time in school and may also have to travel to official and approved training institutes that can manage and staff these longer, more intensive training programmes. These more academically oriented training venues provide opportunities for trainees to be exposed to other health professionals and gain confidence working in different settings, but the training may also become less connected and less relevant to the local contexts where CHWs will work.

The single strong recommendation related to training in the WHO guideline proposes that marital status not be a criterion for selecting CHWs for training and deployment. The guidelines call for selection of candidates who are first approved by and acceptable to the community where they will be working and who have the minimum level of education appropriate to the tasks for which they will be trained and with the necessary cognitive abilities, integrity, motivation, interpersonal skills, commitment to community service, and a public service ethos. Community participation in the recruitment and selection process not only enhances the appropriateness of the persons selected, but it also “enables a dialogue between community members and health organizations, helping them understand local issues” [37].

As the package of services expands, the training of CHWs needs to become more professionalized and better integrated into the health system [71, 72]. If not, CHWs can become overworked, burned out, and frustrated [73]. Questions then arise about the benefits and polyvalent versus specialized CHWs to support specific subpopulations or to provide a more targeted set of services, such as screening and support for chronic disease management [3, 6]. (This is an issue we discuss elsewhere in this series [11].) There is no simple way out of this dilemma, but as more countries and health systems shift towards handling higher burdens of chronic disease, testing different approaches to integrated versus more specialized roles for CHWs will help guide policy and best practices.

At the same time, as the demand for highly skilled and professionalized CHWs is growing, appropriate and invaluable roles remain for lower-level CHWs, often working at the neighbourhood level with a smaller scope of responsibilities and on a voluntary basis. These CHWs, such as the Women’s Development Army (WDA) members in Ethiopia (see Box 1), are able to have frequent contact with their neighbours and focus on promoting healthy household behaviours, identifying pregnant women, and linking households to higher levels of care when needed. In addition, these lower-level CHWs are directly connected to, trusted by, and have first-hand understanding of the poorest and otherwise socially marginalized sections of communities with the most limited access to facilities. Such volunteer CHWs are often trained and supervised by more professionalized cadres of CHWs, and they rely on job aids such as flip charts and culturally appropriate approaches such as songs, stories, and role playing to share health information and to demonstrate healthy behaviours [74, 75]. In addition, collaborations between different cadres of CHWs can support the effective provision of services such as home-based neonatal care (HBNC) as is done by the NGO SEARCH in Maharashtra, India, as well as in other programmes [76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Finally, female CHWs, such as the female community health volunteers (FCHVs) in Nepal [83,84,85] and the volunteer female CHWs in Rwanda (the animatrice de santé maternelle [ASM] and the female member of a pair of CHWs called a binôme) [86] have the ability to promote women’s empowerment and social solidarity as well as to address the social determinants of health in ways that professionalized CHWs will not have time to do.

In our haste and under various societal pressures to modernize and professionalize large-scale CHW programmes, we must not forget the value and the unique contributions that can be made by community-embedded, sustainable, and trusted volunteers and workers who have no intention to leave their community.

Key message 1 |

Professionalism of CHW training does not negate the invaluable contributions of volunteers working in community settings to improve the health of populations. |

Assuring quality and performance selection of CHWs, job-design, training approaches, job-aids, task shifting, and strategies for achieving high performance and quality

The responses of health systems in low- and middle-income countries to the challenges and opportunities they face have important implications for the roles and training of CHWs and their relationships with health facility staff—both clinicians and managers. CHWs have contributed to the progress made by health systems in many countries. However, in order to continue this progress, greater equity in service provision and improved overall CHW programme performance and quality will be required. This calls for new strategies, including a greater emphasis on integration of community-based activities with facilities.

The WHO guideline on CHWs does indicate a general consensus that inadequate training will leave CHWs unprepared for their role and most certainly adversely affect their level of motivation and commitment, not to mention the quality of their work [37]. The length of training should be based on the scope of work and competencies required, the trainees’ pre-existing level of knowledge and skills, and other contextual factors. Most of all, the duration of training should be sufficient to ensure that the desired competencies and expertise are achieved but also that they are feasible, acceptable, and affordable [37]. However, there is not a strong evidence base upon which to make decisions regarding what kind of trainings and what lengths are most effective.

Selection of CHWs

Some programmes, like the Afghanistan programme, deliberately have both male and female CHWs in a community and encourage selection of men and women who are related so that they can work together [92]. The selection of women is sometimes constrained by educational requirements, leading to an under-representation of women in the CHW workforce. The effectiveness of male CHWs can be restricted by their gender, particularly in discussing issues related to sex and reproduction [93]. Examples exist of successful programmes that have selected CHWs from among the poor [94]. Even when CHWs are selected from among the poorer members of a community, other factors can still impede success.

Dual-cadre models

The emerging role for CHWs is that of a multipurpose, professionally trained, and salaried worker who brings services closer to the community and coordinates with other health professionals when patients require additional care. Increasingly, these more highly trained CHWs are complemented by village volunteers who serve a smaller number of households. For instance, in Ethiopia, the HEW, who serves about 500 households or 2500 people, WDA volunteer leaders who coordinate 30 or so households [95]. Another example of the dual-cadre approach is in the BRAC CHW programme (see Box 2), where a higher-level, salaried shasthya kormi, who is herself a CHW, supports the lower-level shasthya shebika. When a shasthya shebika identifies a new pregnancy or birth, she calls on her shasthya kormi to come to the home to provide care and education, which are beyond the scope of work of the shasthya shebika [96, 97].

Training approaches

Training for CHWs has evolved over the years and has recently expanded in terms of scope and modalities. More emphasis has also been placed on application of knowledge through simulations, supervised practice, being able to demonstrate skills under observation, and peer assessments. In addition, attention to how CHWs can most effectively learn has taken on a higher priority in recent years. Increased focus on storytelling, case-based learning, and peer learning and teaching have helped align CHW training with cultural norms for sharing information with each other.

Teaching problem-solving skills and other more complex tasks and responsibilities has required other training approaches beyond basic classroom lectures and memorization. Training is also needed on how to interact with families and communities and how to handle challenging situations that they will certainly face: conflict within and between families (including gender-based violence), lack of medicines and supplies, lack of supervision, and how to deal with health problems for which they do not have adequate training (e.g., severely ill patients, mental health problems, social conflicts) but which communities expect them to be able to address. Finally, and critically, trainees need guidance on how to deal with stress and burnout arising from these issues as well as from the common issues of being stigmatized and overworked.

The WHO guideline on CHWs recommended that training encompass at a minimum: (1) promotive and preventive services, (2) identification of family health and social needs, and risk factors for them, (3) integration within the wider healthcare system (referral, collaboration with other health workers, patient tracing, disease surveillance, monitoring and data collection, and analysis and use of data), (4) social and environmental determinants of health, (5) provision of psychosocial support, (6) strengthening of interpersonal skills related to confidentiality, communication, community engagement, and mobilization, and (7) personal safety [37]. The guideline concluded that training for diagnosis, treatment, and care be added to this basic set of domains when these are a part of the expected role of the CHW and when regulations on scope of practice are not prohibitive [37].

Although the level of evidence was low, the WHO guideline for CHWs also made a conditional recommendation that the content of training be a balance of theory-focused knowledge and practice-focused skills, including supervised practical experience [37]. The WHO guideline recommends that every effort should be made to provide training in or near the community and with learning methods in a language appropriate for the trainees. When possible, interprofessional training (with other types of health workers) should be encouraged, as well as the creation of a positive training environment. E-learning can supplement other modalities of training and is particularly appropriate for follow-up and refresher training [37]. This has been found in Ethiopia and Bangladesh (see Boxes 1 and 2), and has also been found to be cost effective [98] and to support knowledge exchange between CHWs [99].

An important but unexplored field of inquiry concerns the pros and cons of what kind of organization is best suited to provide training for CHWs and at what level in the healthcare or educational system. In some countries, universities and ministries of education take responsibility for training CHWs, while in others, the training is provided by the MOH or by technical institutes within the MOH. The level of centralization or decentralization of training is also a consideration, and how far away from home CHWs have to travel to attend training is an important issue that training programmes have to face.

Task shifting

Since the initial development of the concept of the integrated continuum of care in maternal, neonatal, and child health (MNCH) was developed, the scope of activities recommended for traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and CHWs has been expanded beyond health promotion. This is particularly important for implementation in populations in which access to facility-based healthcare is limited. These recommendations include distribution of nutrition supplements to pregnant women, the provision of bed nets and monthly intermittent presumptive treatment (IPT) of malaria, the administration of misoprostol to prevent postpartum haemorrhage for home deliveries, and the provision of injectable contraceptives [100]. There is accumulating experience with community-based implementation of nutrition supplementation [101, 102], malaria control [103, 104], misoprostol [105, 106], and injectable contraceptives [107, 108]. There is also growing support for the benefits of training of TBAs in clean delivery and cord care, immediate newborn care and referral of complications [109], newborn resuscitation [110], and organized postnatal home visits and management of neonatal infections [111, 112].

Job aids

Professionalized CHWs are also often expected to provide training to other volunteer cadres, and most CHWs are expected to provide health education to community members. What sorts of visual aids and tools are most helpful for this to be done effectively? For example, the shasthya kormis in the BRAC programme in Bangladesh have recently started this, using computer tablets for this purpose (see Box 2). Tablets are emerging as an important resource for showing key health messages through drawings, thereby eliminating the need for heavy paper flip charts.

Shasthya kormis are now also using tablets to record census data as well as case records of pregnant women (see Box 2). An Android-based mHealth system was used in a similar way to survey a population of two million individuals in Western Kenya for TB and HIV. Several hundred government-trained CHWs offered home-based counselling and testing for HIV along with sputum collection from individuals with symptoms of TB. Data were downloaded to a central server and then deleted from the CHWs’ phones for reasons of confidentiality. Collated information was provided to the clinics that were supervising specific communities. The CHWs found the system easy to use and preferable to the previous paper-and-pen alternatives. The system was also found to be more cost-effective than the pen-and-paper system [113].

Strategies for improving performance and quality care

The comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based PHC in improving MNCH [114] identified four community-based strategies used by effective projects: a) treatment and/or referral of sick children by parents or CHWs, b) routine systematic visitation of all homes, c) facilitator-led participatory women’s groups, and d) provision of outreach services by facility-based mobile health teams [115]. Most importantly, most (78%) of the studies included in the review that measured equity effects of community-based programmes reported that these effects were “pro-equitable”, meaning that the effect of the programme was more favourable for the most disadvantaged segment of the population served than for the rest [116].

Participatory women’s groups have been particularly successful in changing complex sets of behaviours that are embedded in cultural belief systems. Recent experience has demonstrated that it is in the realm of pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn care that participatory women’s groups have been effective. Both maternal and neonatal mortality rates have been reduced in communities, in proportion to the numbers of pregnant women participating [117]. Four mechanisms seem to explain the impact of the women’s groups. The first is that during their pregnancy women learn about appropriate care and how to prevent and manage problems. This process is enhanced by discussion and learning from each other. The second is the development of confidence. This is particularly important when dealing with mothers-in-law or other authority figures in the community who are advocating traditional beliefs and practices or resisting healthy practices. The third is the dissemination of information to others in the community. In addition to the formal community meetings, there was continued informal sharing among family members and neighbours. In one project in Malawi, there was more intentional home visiting to share information. Finally, the fourth mechanism is building the community’s capacity to take action [118, 119].

Training needs to provide all stakeholders, not just CHW trainees, with exposure to evidence-based new approaches such as those described here so that they can at least begin to sense the potential of modifying their strategies to improve performance and quality of the CHW programme.

Key message 2 |

Assuring quality of CHW training does not just entail more training, but rather ensuring that training is relevant, that associated job aids are available, and that tasks and expectations are aligned with the training provided. |

Discussion

Scaling up of CHW programmes includes expanding population coverage, of course, but it can also include improving quality and adding new components to existing programmes [123, 124]. Scale-up often builds on the experience of a pilot phase or on the experience of more widespread programme implementation. As such, when designing the adaptation or expansion of a CHW programme, it is important to consider who all the stakeholders will be, how their roles will change or grow in the new programme, and what kinds of training needs may arise for them. Secondly, considering who the best-placed trainers and mentors are for different stakeholders is essential. It is also important to consider the policy and regulatory standards and expectations for a particular context as well as global best practices relevant to the revised programme.

Since the roles of many stakeholders often need to change when programmes scale up, training needs are not limited to only CHWs. In fact, some of the most important training related to scaling CHW programmes is often training for other cadres of PHC workers, such as nurses and physicians, and supervisors and managers of health systems from the district up to national level. Training these other cadres can help them understand how to effectively collaborate with and support CHWs and also to avoid or allay concerns about CHWs contributing competition, confusion, or poor quality of care to the existing health system. National-level and mid-level buy-in and support for scale-up of CHWs includes training and support for the managers and supervisors that are overseeing these programmes at several levels. The entire PHC system needs to adapt as CHW programmes are introduced and scaled up.

Defining orientation and/or training requirements of each stakeholder and then determining who will be responsible for designing and delivering the orientation and training is the second critical consideration. Attention to who is best-placed and appropriate to teach CHWs is important in ensuring context-specific content [125]. Some of the key trainers that have been found to be appropriate include senior CHWs, experts with first-hand experience of the context where these workers are based, community leaders, and others with specific technical or other skill sets [126,127,128]. Training for other clinical cadres and managers can include sharing and learning peers, experiences from working directly with CHWs, and guidance and encouragement from higher levels of government or experts from different development partners. The WHO guideline advises that faculty for the training of CHWs should ideally include other health workers, thereby facilitating the incorporation of CHWs as members of multidisciplinary PHC teams, and the faculty should also include supervisors of CHWs. The creation of a safe and supportive training environment is critical, with special attention to the needs of women trainees and of trainees who are members of minority and other vulnerable groups. Approaches for training diverse stakeholders may also include implications for setting up training-of-trainer (TOT) structures in order to scale training rapidly.

Next, scaling up of CHW programmes also needs to consider existing regulatory frameworks and changes in these frameworks that are needed. These frameworks and the policy approval processes associated with creating them have important implications for training. In addition, best practices from the WHO guideline on CHWs also need to be consulted and aligned with the national context.

The WHO guideline considers that competency-based formal certification has many benefits, including increasing the self-esteem of CHWs and the respect they receive from other health workers. It is also useful as CHWs transfer to other sites and other employers, and as they apply for further education and training. It provides protection to the public from those who do not have the requisite skills and training yet purport to be qualified. And it can provide a basis for reimbursement for CHW services. Finally, WHO recommends that efforts be made to establish a formal accreditation process for educational institutions that provide training for CHWs [37]. In addition to global and national policies to guide training at scale, considering roles for village health councils or village health committees in the training process can be valuable to provide local context and community-level engagement [129, 130]. These committees also often include CHWs as members.

We recognize several important limitations of our paper. While the paper covers a lot of ground, it cannot explore every aspect of CHW training in depth, and for some countries, even basic data were missing. Further, the case examples of training in Ethiopia and Bangladesh and for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic provide a more in-depth view of training of CHWs, but many more case examples could be cited. Finally, we acknowledge that this paper was not able to make specific recommendations for CHW training programmes given the wide variation in programme contexts, approaches, and goals.

Finally, in order for CHW programmes to sustainably scale up high-quality training, adequate resources are necessary. Building the scaled-up training programme and the evidence of impact is often an iterative process that includes experimenting with different approaches and evaluating what is working well and where challenges arise in order to modify accordingly [131].

The rapid progression of the COVID-19 pandemic throughout the world and the need of CHWs to quickly acquire the skills they need to contribute to pandemic control led to challenges and opportunities that are relevant to this paper. Box 3 provides an overview of some of the training approaches used at scale in CHW programmes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Message 3 |

Scaling up CHW training requires providing knowledge and skills not only to CHWs, but also to ensuring that other cadres that they work with and relevant regulatory bodies are prepared to acknowledge, certify, and integrate these workers. |

Conclusion

This paper has laid out a set of considerations across three broad themes—professionalization, quality and performance, and scale-up—related to training for CHWs. While every context is different and requires consideration for how approaches need to be adapted, as evidence continues to mount some cross-cutting approaches and considerations are becoming clear. Currently, there is a great deal of support and enthusiasm for CHW programmes. If this can be leveraged now to further embed well-trained CHWs into strong PHC systems, their contributions and impact will support continued future investment and action to ensure that they remain a critical and well-supported cadre of the PHC workforce.

Training is a comprehensive and dynamic element of CHW programmes that needs to be well funded and professionalized (meaning that there is ongoing assessment of quality and continuous quality improvement). Training must be seen as much more than just pre-service training, but rather as ongoing iterative training. Training for effective CHW programmes also needs to be seen not only as training of CHWs but also as training the community, supervisors of CHWs, and others within the health system in order to help these stakeholders appreciate, understand, and make effective use of CHWs.

CHW roles will continue to change over time, and therefore ongoing and dynamic training updates will be an essential element of an effective CHW programme. This includes adding trainings for new evidence-based interventions and approaches in response to unmet, new, and emerging population health needs. Public health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, bring urgent further attention to the need for ongoing and responsive training of CHWs.

Availability of data and materials

All of the data and findings reported in this paper are from appropriately cited sources for from the personal experience of the authors and their colleagues.

Abbreviations

- ANM:

-

Auxiliary nurse midwife

- ASHA:

-

Accredited social health activist

- CHV:

-

Community health volunteer

- CHW:

-

Community health worker

- COVID:

-

Coronavirus disease

- HBNC:

-

Home-based neonatal care

- HEW:

-

Health extension worker

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- iCCM:

-

Integrated community case management (of childhood illness)

- MNCH:

-

Maternal, neonatal, and child health

- NCDs:

-

Noncommunicable diseases

- NGO:

-

Nongovernmental organization

- PHC:

-

Primary healthcare

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- TOT:

-

Training of trainers

- WDA:

-

Women’s Development Army

References

Perry H, Zulliger R, Rogers M. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:399–421.

Freeman PA, Schleiff M, Sacks E, Rassekh BM, Gupta S, Perry HB. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 4. Child health findings. J Glob Health. 2017;7: 010904.

Mishra SR, Neupane D, Preen D, Kallestrup P, Perry HB. Mitigation of non-communicable diseases in developing countries with community health workers. Glob Health. 2015;11:43.

Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, Pariyo G, Rao KD, Cometto G, Perry HB. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16:39.

Gross K, Pfeiffer C, Obrist B. “Workhood’’’-a useful concept for the analysis of health workers’ resources? An evaluation from Tanzania.” BMC Health. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-55.

Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, Nieman CL, Jou JH, Lin FR, Gatlin LN, Han H-R. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302987a.

El Arifeen S, Christou A, Reichenbach L, Osman FA, Azad K, Islam KS, Ahmed F, Perry HB, Peters DH. Community-based approaches and partnerships: innovations in health-service delivery in Bangladesh. Lancet. 2013;382:2012–26.

Callaghan-Koru JA, Gilroy K, Hyder AA, George A, Nsona H, Mtimuni A, Zakeyo B, Mayani J, Cardemil CV, Bryce J. Health systems supports for community case management of childhood illness: lessons from an assessment of early implementation in Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:55–55.

Ahmed SM, Hossain MA, RajaChowdhury AM, Bhuiya AU. The health workforce crisis in Bangladesh: shortage, inappropriate skill-mix and inequitable distribution. Hum Resour Health. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-9-3.

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, Odgaard-Jensen J, Johansen M, Aja GN, Zwarenstein M, Scheel I. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:1–211.

Glenton C, Javadi D, Perry H. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 5. Roles and tasks. BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;24–32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00748-4.

Haines A, de Barros EF, Berlin A, Heymann DL, Harris MJ. National UK programme of community health workers for COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;395:1173–5.

Varghese J, Kutty VR, Paina L, Adam T. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: understanding the growing complexity governing immunization services in Kerala, India. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12:47–47.

George A, Scott K, Garimella S, Mondal S, Ved R, Sheikh K. Anchoring contextual analysis in health policy and systems research: a narrative review of contextual factors influencing health committees in low and middle income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:159–67.

Sacks E, Swanson RC, Schensul JJ, Gleave A, Shelley KD, Were MK, Chowdhury AM, LeBan K, Perry HB. Community involvement in health systems strengthening to improve global health outcomes: a review of guidelines and potential roles. Int Q Commun Health Educ. 2017;37:139–49.

Kok MC, Kane SS, Tulloch O, Ormel H, Theobald S, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, Broerse JEW, De Koning KAM. How does context influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? Evidence from the literature. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:13–13.

Huicho L, Dieleman M, Campbell J, Codjia L, Balabanova D, Dussault G, Dolea C. Increasing access to health workers in underserved areas: a conceptual framework for measuring results. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:357–63.

Crigler L, Fort AL, Diez OD, Gearon S, Gyuzalyan H. Training is not enough: factors that influence the performance of healthcare providers in Armenia, Bangladesh, Bolivia, and Nigeria. Perform Improv Q. 2006;19:99–116.

Rowe AK, Rowe SY, Peters DH, Holloway KA, Chalker J, Ross-Degnan D. Effectiveness of strategies to improve health-care provider practices in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1163–75.

Cometto G, Ford N, Pfaffman-Zambruni J, Akl EA, Lehmann U, McPake B, Ballard M, Kok M, Najafizada M, Olaniran A, et al. Health policy and system support to optimise community health worker programmes: an abridged WHO guideline. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1397–404.

Perry HB. 9ed. Health for the people: national community health programs from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00WKKN.pdf. Accessed 18 April 2021.

Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Suphanchaimat R, Patcharanarumol W, Sawaengdee K, Putthasri W. Health workforce contributions to health system development: a platform for universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:874–80.

Pozo-Martin F, Nove A, Lopes SC, Campbell J, Buchan J, Dussault G, Kunjumen T, Cometto G, Siyam A. Health workforce metrics pre- and post-2015: a stimulus to public policy and planning. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:14–14.

Hodgins S, Lewin S, Glenton C, LeBan K, Crigler L, Musoke D, Kok M, Perry H. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 1. Introduction and tensions confronting programs. BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00752-8.

Afzal M, Pariyo G, Perry H. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 2. Planning, coordination, and partnerships. BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00753-7.

Lewin S, Lehmann U, Perry H. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 3. Program governance. BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00749-3.

Masis L, Gichaga A, Lu C, Perry H. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 4. Program financing. BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00751-9.

Carpenter C, Musoke D, Crigler L, Perry H. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 7. Supervision. BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00754-6.

Colvin C, Hodgins S, Perry H. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 8. Incentives and remuneration. BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00750-w.

LeBan K, Kok M, Perry H. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 9. CHWs' relationships with the health system and the community. BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00756-4.

Kok M, Crigler L, Kok M, Ballard M, Musoke D, Hodgins S, Perry H. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 10. Program performance and its assessment. BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00758-2.

Perry H, Crigler L, Kok M, Ballard M, Musoke D, LeBan K, Lewin S, Scott K, Hodgins S. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 11. Leading the way to "Health for All". BMC Health Res Policy Syst. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00755-5.

Crigler L, Glenton C, Hodgins S, LeBan K, Lewin S, Perry H. Developing and Strengthening Community Health Worker Programs at Scale: A Reference Guide for Program Managers and Policy Makers. Perry H ed. Washington, DC: USAID-MCHIP; 2014.

Health for the People: National Community Health Worker Programs from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Baltimore, MD: USAID and Maternal and Child Survival Program; 2020.

Aitken I. Training community health workers for large-scale community-based primary health care programs. In: Perry H, Crigler L, editors. Developing and strengthening community health worker programs at scale: a reference guide for program managers and policy makers. Washington, DC: Maternal and Child Health Integrated Programs/United States Agency for International Development; 2014. p. 9-1-9–24.

Scott K, Beckham S, Gross M, Pariyo G, Rao K, Perry H. The state-of-the-art knowledge on integration of community-based health workers in health systems: a systematic review of literature reviews. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

WHO. WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275474/9789241550369-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 18 April 2021.

O’Brien MJ, Squires AP, Bixby RA, Larson SC. Role development of community health workers: an examination of selection and training processes in the intervention literature. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:S262-269.

Malik AU, Willis CD, Hamid S, Ulikpan A, Hill PS. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: advice seeking behavior among primary health care physicians in Pakistan. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-12-43.

Roberton T, Applegate J, Lefevre AE, Mosha I, Cooper CM, Silverman M, Feldhaus I, Chebet JJ, Mpembeni R, Semu H, et al. Initial experiences and innovations in supervising community health workers for maternal, newborn, and child health in Morogoro region, Tanzania. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:19.

Kok MC, Vallières F, Tulloch O, Kumar MB, Kea AZ, Karuga R, Ndima SD, Chikaphupha K, Theobald S, Taegtmeyer M. Does supportive supervision enhance community health worker motivation? A mixed-methods study in four African countries. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33:988–98.

Henry JV, Winters N, Lakati A, Oliver M, Geniets A, Mbae SM, Wanjiru H. Enhancing the supervision of community health workers with whatsapp mobile messaging: qualitative findings from 2 low-resource settings in Kenya. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2016;4:311–25.

Zulu JM, Kinsman J, Michelo C, Hurtig A-K. Hope and despair: community health assistants’ experiences of working in a rural district in Zambia. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:30–30.

Sennun P, Suwannapong N, Howteerakul N, Pacheun O. Participatory supervision model: building health promotion capacity among health officers and the community. Rural Remote Health [electronic resource]. 2006;6:440–440.

Denno DM, Hoopes AJ, Chandra-Mouli V. Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:S22-41.

De Allegri M, Sanon M, Sauerborn R. “To enrol or not to enrol?”: A qualitative investigation of demand for health insurance in rural West Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1520–7.

Nekoei-Moghadam M, Parva S, Amiresmaili BM. Health literacy and utilization of health services in Kerman Urban Area 2011. J Toloo-e-behdasht. 2013;11:123–34.

Kardanmoghadam V, Movahednia N, Movahednia M, Nekoei-Moghadam M, Amiresmaili M, Moosazadeh M, Kardanmoghaddam H. Determining patients’ satisfaction level with hospital emergency rooms in Iran: a meta-analysis. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7:260–9.

Nekoei Moghadam M, Amiresmaili M, Sadeghi V, Zeinalzadeh AH, Tupchi M, Parva S. A qualitative study on human resources for primary health care in Iran. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2018;33:e38–48.

Sandiford P, Cassel J, Montenegro M, Sanchez G. The impact of women’s literacy on child health and it interaction with access to health services. J Demogr. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000148216.

Catalani CE, Findley SE, Matos S, Rodriguez R. Community health worker insights on their training and certification. Prog Commun Health Partnersh. 2009;3:201–2.

Brown H, Green MA. At the service of community development: the professionalization of volunteer work in Kenya and Tanzania. Afr Stud Rev. 2015;58:63–84.

Scheil-Adlung X. Global evidence on inequities in rural health protection: new data on rural deficits in health coverage for 174 countries. International Labour Organization: Extension of Social Security; 2015.

Maes K, Kalofonos I. Becoming and remaining community health workers: perspectives from Ethiopia and Mozambique. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:52–9.

Kenny A, Hyett N, Sawtell J, Dickson-Swift V, Farmer J, O’Meara P. Community participation in rural health: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:1–8.

De Costa A, Diwan V. “Where is the public health sector?” Public and private sector healthcare provision in Madhya Pradesh, India. Health Policy. 2007;84:269–76.

Acharya SS. Access to health care and patterns of discrimination: a study of Dalit children in selected villages of Gujarat and Rajasthan. Child Soc Exclusion Dev. 2010;1:1–38.

Buchan J, Fronteira I, Dussault G. Continuity and change in human resources policies for health: lessons from Brazil. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9:17–17.

Ahmed SM, Hossain MA, Rajachowdhury AM, Bhuiya AU. The health workforce crisis in Bangladesh: shortage, inappropriate skill-mix and inequitable distribution. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9:3.

AbuAlRub RF, El-Jardali F, Jamal D, Iblasi AS, Murray SF. The challenges of working in underserved areas: a qualitative exploratory study of views of policy makers and professionals. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:73–82.

El-Jardali F, Dimassi H, Jamal D, Tchaghchagian V. Comparing reasons for nurse migration against intent to leave Lebanon: a two-hosptial case study. Middle East J Nurs. 2009:26–33.

Sacks E, Alva S, Magalona S, Vesel L. Examining domains of community health nurse satisfaction and motivation: results from a mixed-methods baseline evaluation in rural Ghana. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:81.

Bourgeault IL, Kuhlmann E, Neiterman E, Wrede S. How can optimal skill mix be effectively implemented and why? WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2008;1–23.

Daviaud E, Chopra M. How much is not enough? Human resources requirements for primary health care: a case study from South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:46–51.

Buse K, Hawkes S. Health in the sustainable development goals: ready for a paradigm shift? Glob Health. 2015;11:13.

Mokwena K, Mokgatle-Nthabu M, Madiba S, Lewis H, Ntuli-Ngcobo B. Training of public health workforce at the National School of Public Health: meeting Africa’s needs. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:949–54.

Rowe LA, Brillant SB, Cleveland E, Dahn BT, Ramanadhan S, Podesta M, Bradley EH. Building capacity in health facility management: guiding principles for skills transfer in Liberia. Hum Resour Health. 2010;8:5–5.

Mash BJ, Mayers P, Conradie H, Orayn A, Kuiper M, Marais J. How to manage organisational change and create practice teams: experiences of a South African primary care health centre. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2008;21:132–132.

Kotecha J, Han H, Green M, Roberts S, Brown JB, Harris SB, Russell G, Webster-Bogaert S, Fournie M, Thind A, Reichert S. Influence of a quality improvement leanring collaborative program on team functioning in primary healthcare. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33:222–30.

Bracho A, Lee G, Giraldo G, De Prado RM, Latino Health Access Collective. Recruiting the heart, training the brain: the work of Latino health access. Berkeley, CA: Hesperian Health Guides; 2016.

Maes K. “Volunteers are not paid because they are priceless”: community health worker capacities and values in an AIDS treatment intervention in urban Ethiopia. Med Anthropol Q. 2015;29:97–115.

Huang W, Long H, Li J, Tao S, Zheng P, Tang S, Abdullah AS. Delivery of public health services by community health workers (CHWs) in primary health care settings in China: a systematic review (1996–2016). Glob Health Res Policy. 2018;3:18.

Uskun E, Ozturk M, Kisioglu AN, Kirbiyik S: Burnout and job satisfaction among staff in Turkish community health services. 2005; 10: P1–P7

Perry H, Morrow M, Borger S, Weiss J, DeCoster M, Davis T, Ernst P. Care groups I: an innovative community-based strategy for improving maternal, neonatal, and child health in resource-constrained settings. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2015;3:358–69.

Seward N, Neuman M, Colbourn T, Osrin D, Lewycka S, Azad K, Costello A, Das S, Fottrell E, Kuddus A, et al. Effects of women’s groups practising participatory learning and action on preventive and care-seeking behaviours to reduce neonatal mortality: a meta-analysis of cluster-randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002467–e1002467.

Lassi Z, Haider B, Bhutta Z. Community-based intervention packages for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes. The Cochrane Collaboration 2010.

Baqui AH, Rosecrans AM, Williams EK, Agarwal PK, Ahmed S, Darmstadt G. NGO facilitation of a government community-based maternal and neonatal health programme in rural India: improvements in equity. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23:234–43.

Bang A, Bellad R, Gisore P, Hibberd P, Patel A, Goudar S, Esamai F, Goco N, Meleth S, Derman RJ, et al. Implementation and evaluation of the Helping Babies Breathe curriculum in three resource limited settings: does Helping Babies Breathe save lives? A study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:116.

Bang AT, Baitule SB, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD, Bang RA. Low birth weight and preterm neonates: can they be managed at home by mother and a trained village health worker? J Perinatol. 2005;25(Suppl 1):S72-81.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Baitule SB, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD. Management of birth asphyxia in home deliveries in rural Gadchiroli: the effect of two types of birth attendants and of resuscitating with mouth-to-mouth, tube-mask or bag-mask. J Perinatol. 2005;25(Suppl 1):S82-91.

Bang AT, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD, Baitule SB, Bang RA. Neonatal and infant mortality in the ten years (1993 to 2003) of the Gadchiroli field trial: effect of home-based neonatal care. J Perinatol. 2005;25(Suppl 1):S92-107.

Bang AT, Bang RA, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD, Baitule SB. Reduced incidence of neonatal morbidities: effect of home-based neonatal care in rural Gadchiroli, India. J Perinatol. 2005;25(Suppl 1):S51-61.

Perry H, Akin-Olugbade L, Lailari A, Son Y. A comprehensive description of the three National Community Health Worker Programs and contributions to maternal and child health and primary health care: case studies from America (Brazil), Africa (Ethiopia) and Asia (Nepal). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2016.

Shrestha S. A conceptual model for empowerment of the female community health volunteers in Nepal. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2003;16:318–27.

Schwarz D, Sharma R, Bashyal C, Schwarz R, Baruwal A, Karelas G, Basnet B, Khadka N, Brady J, Silver Z, et al. Strengthening Nepal’s female community health volunteer network: a qualitative study of experiences at two years. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:473.

Napier H, Mugeni C, Crigler L. Rwanda’s Community Health Worker Program. In: Perry H, editor. National Community Health Programs: descriptions from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Washington, DC: USAID/Jhpiego/Maternal and Child Survival Program; 2020. p. 320–44.

Exepmlars in Global Health. Overview: community health workers in Ethiopia. https://www.exemplars.health/topics/community-health-workers/ethiopia. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

Damtew ZA, Schleiff M, Worku K, Tesfaye C, Lemma S, Abiodun O, Haile MS, Carlson D, Moen A, Perry H. Ethiopia: expansion of primary health care through the health extension program. In: Bishai D, Schleiff M, editors. Achieving health for all: primary health care in action. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2020. p. 180–98.

Ye-Ebiyo Y, Yayehyirad K, Yohannes AG, Girma S, Desta H, Seyoum A, Teklehaimanot A. Study on health extension workers: access to information, continuing education and reference materials. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2007;21:240–5.

Miller NP, Amouzou A, Tafesse M, Hazel E, Legesse H, Degefie T, Victora CG, Black RE, Bryce J. Integrated community case management of childhood illness in Ethiopia: implementation strength and quality of care. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91:424–34.

Teklu A, Alemayehu Y. National Assessment of the Ethiopian Health Extension Program. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: MERQ Consultancy PLC; 2019.

Aitken I, Arwal S, Edward A, Rohde J. The community-based health care system of Afghanistan. In: Perry H, editor. Health for the people: National Community Health Programs from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Baltimore, MD: USAID/Jhpiego; 2020. p. 23–41.

Rafiq MY, Wheatley H, Mushi HP, Baynes C. Who are CHWs? An ethnographic study of the multiple identities of community health workers in three rural districts in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:712.

McCollum R, Gomez W, Theobald S, Taegtmeyer M. How equitable are community health worker programmes and which programme features influence equity of community health worker services? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:419.

Damtew Z, Lemma S, Zulliger R, Moges A, Teklu A, Perry H. Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program. In: Perry H, editor. Health for the people: National Community Health Programs from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Washingon, DC: USAID/Maternal and Child Survival Program; 2020. p. 75–86.

Quayyum Z, Khan MN, Quayyum T, Nasreen HE, Chowdhury M, Ensor T. “Can community level interventions have an impact on equity and utilization of maternal health care”—evidence from rural Bangladesh. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:22.

Joardar T, Javadi D, Gergen J, Perry H. The BRAC Shasthya Shebika and Shasthya Kormi Community Health Workers in Bangladesh. In: Perry H, editor. Health for the people: national community health programs from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Washington, DC: USAID/Jhpiego/Maternal and Child Survival Program; 2020.

Sissine M, Segan R, Taylor M, Jefferson B, Borrelli A, Koehler M, Chelvayohan M. Cost comparison model: blended eLearning versus traditional training of community health workers. Online J Public Health Inform. 2014;6:196.

Campbell N, Schiffer E, Buxbaum A, McLean E, Perry C, Sullivan TM. Taking knowledge for health the extra mile: participatory evaluation of a mobile phone intervention for community health workers in Malawi. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2:23–34.

WHO. WHO Recommendations: optimizing health worker roles to improve access to key maternal and newborn health interventions through task shifting. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77764/1/9789241504843_eng.pdf. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

Goudet S, Murira Z, Torlesse H, Hatchard J, Busch-Hallen J. Effectiveness of programme approaches to improve the coverage of maternal nutrition interventions in South Asia. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(Suppl 4): e12699.

Kavle JA, Landry M. Community-based distribution of iron-folic acid supplementation in low- and middle-income countries: a review of evidence and programme implications. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:346–54.

Win Han O, Gold L, Moore K, Agius PA, Fowkes FJI. The impact of community-delivered models of malaria control and elimination: a systematic review. Malar J. 2019;18:269.

Orobaton N, Austin AM, Abegunde D, Ibrahim M, Mohammed Z, Abdul-Azeez J, Ganiyu H, Nanbol Z, Fapohunda B, Beal K. Scaling-up the use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: results and lessons on scalability, costs and programme impact from three local government areas in Sokoto State, Nigeria. Malar J. 2016;15:533.

Smith JM, Gubin R, Holston MM, Fullerton J, Prata N. Misoprostol for postpartum hemorrhage prevention at home birth: an integrative review of global implementation experience to date. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:44.

Hobday K, Hulme J, Prata N, Wate PZ, Belton S, Homer C. Scaling up misoprostol to prevent postpartum hemorrhage at home births in mozambique: a case study applying the ExpandNet/WHO framework. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7:66–86.

Kennedy CE, Yeh PT, Gaffield ML, Brady M, Narasimhan M. Self-administration of injectable contraception: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4: e001350.

Weidert K, Gessessew A, Bell S, Godefay H, Prata N. Community health workers as social marketers of injectable contraceptives: a case study from Ethiopia. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5:44–56.

Sibley L, Sipe T, Barry D. Traditional birth attendant training for improving health behaviours and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8: CD005460.

Patel A, Khatib MN, Kurhe K, Bhargava S, Bang A. Impact of neonatal resuscitation trainings on neonatal and perinatal mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2017;1: e000183.

Shukla VV, Carlo WA. Review of the evidence for interventions to reduce perinatal mortality in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2020;7:2–8.

Tiruneh GT, Shiferaw CB, Worku A. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home-based postpartum care on neonatal mortality and exclusive breastfeeding practice in low-and-middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:507.

Rajput ZA, Mbugua S, Amadi D, Chepngeno V, Saleem JJ, Anokwa Y, Hartung C, Borriello G, Mamlin BW, Ndege SK, Were MC. Evaluation of an Android-based mHealth system for population surveillance in developing countries. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:655–9.

Perry HB, editor. Engaging communities for improving mothers’ and children’s health: reviewing the evidence of effectiveness in resource-constrained settings. Edinburgh, Scotland, UK: Edinburgh University Global Health Society; 2017.

Perry HB, Sacks E, Schleiff M, Kumapley R, Gupta S, Rassekh BM, Freeman PA. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 6. strategies used by effective projects. J Glob Health. 2017;7: e010906.

Schleiff M, Kumapley R, Freeman PA, Gupta S, Rassekh BM, Perry HB. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 5. equity effects for neonates and children. J Glob Health. 2017;7: e010905.

Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A, Houweling TA, Fottrell E, Kuddus A, Lewycka S, et al. Women’s groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1736–46.

Morrison J, Akter K, Jennings HM, Kuddus A, Nahar T, King C, Shaha SK, Ahmed N, Haghparast-Bidgoli H, Costello A, et al. Implementation and fidelity of a participatory learning and action cycle intervention to prevent and control type 2 diabetes in rural Bangladesh. Glob Health Res Policy. 2019;4:19.

Morrison J, Thapa R, Hartley S, Osrin D, Manandhar M, Tumbahangphe K, Neupane R, Budhathoki B, Sen A, Pace N, et al. Understanding how women’s groups improve maternal and newborn health in Makwanpur, Nepal: a qualitative study. Int Health. 2010;2:25–35.

NGO Advisor. Announcing the 2020 TOP 100 SPO/NGO. https://www.ngoadvisor.net/ngoadvisornews/announcing-the-2020-top-100-spo-ngo. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

BRAC. BRAC: Who we are. http://www.brac.net/who-we-are. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

Chowdhury A, Perry H. NGO contributions to community health and primary health care: case studies on BRAC (Bangladesh) and the Comprehensive Rural Health Project, Jamkhed (India). In: Oxford research encyclopedia in global health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2020.https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.56. Available at https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-56?rskey=vf7ygF. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

Taylor D, Taylor C, Taylor J. Empowerment on an unstable planet: from seed of human energy to a scale of global change. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Naimoli JF, Frymus DE, Wuliji T, Franco LM, Newsome MH. A Community Health Worker “logic model”: towards a theory of enhanced performance in low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:56–56.

Pigg SL. Acronyms and effacement: traditional medical practitioners (TMP) in international health development. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:47–68.

Srivastava A, Gope R, Nair N, Rath S, Rath S, Sinha R, Sahoo P, Biswal PM, Singh V, Nath V, et al. Are village health sanitation and nutrition committees fulfilling their roles for decentralised health planning and action? A mixed methods study from rural eastern India. BMC Public Health. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2699-4.

Kitaw Y, Ye-Ebiyo Y, Said A, Desta H, Teklehaimano A. Assessment of the training of the first intake of health extension workers. Ethiopia J Health Dev. 2008. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhd.v21i3.10053.

Nsibande D, Loveday M, Daniels K, Sanders D, Doherty T, Zembe W. Approaches and strategies used in the training and supervision of Health Extension Workers (HEWs) delivering integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood illness in Ethiopia: a qualitative rapid appraisal. Afr Health Sci. 2018;18:188–97.

Scott K, George AS, Harvey SA, Mondal S, Patel G, Ved R, Garimella S, Sheikh K. Beyond form and functioning: understanding how contextual factors influence village health committees in northern India. 2017;1–17.

Scott V, Schaay N, Olckers P, Nqana N, Lehmann U, Gilson L. Exploring the nature of governance at the level of implementation for health system strengthening: the DIALHS experience. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:59–70.

Dahn B, Tamire Woldemarian A, Perry HB, Maeda A, Panjabi R, Merchan N, Vosberg K, Palazuelos D, Lu C, Simon J, Brown D, Heydt P, Qureshi C. 2015. Strengthening primary health care through community health workers: investment case and financing recommendations. http://www.mdghealthenvoy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/CHW-Financing-FINAL-July-15-2015.pdf. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

Raeisi A, Tabrizi JS, Gouya MM. IR of Iran National Mobilization against COVID-19 epidemic. Arch Iran Med. 2020;23:216–9.

Lotta G, Wenham C, Nunes J, Pimenta DN. Community health workers reveal COVID-19 disaster in Brazil. Lancet. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31521-X.

Mc Kenna P, Babughirana G, Amponsah M, Egoeh SG, Banura E, Kanwagi R, Gray B. Mobile training and support (MOTS) service-using technology to increase Ebola preparedness of remotely-located community health workers (CHWs) in Sierra Leone. Mhealth. 2019;5:35.

Wiah SO, Subah M, Varpilah B, Waters A, Ly J, Ballard M, Price M, Panjabi R. Prevent, detect, respond: how community health workers can help in the fight against COVID-19. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/03/27/prevent-detect-respond-how-community-health-workers-can-help-fight-covid-19/. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

Bearak M, Mogotsi B. South African is hunting down the coronavirus with thousands of health workers. https://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/south-africa-is-hunting-down-coronavirus-with-thousands-of-health-workers/. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

McPake B, Dayal P, Herbst CH. Never again? Challenges in transforming the health workforce landscape in post-Ebola West Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17:19.

Goldfield NI, Crittenden R, Fox D, McDonough J, Nichols L, Lee Rosenthal E. COVID-19 crisis creates opportunities for community-centered population health: community health workers at the center. J Ambul Care Manag. 2020;43:184–90.

Goldfield N. Fitting Community-Centered Population Health (CCPH) into the existing health care delivery patchwork: the politics of CCPH. J Ambul Care Manag. 2020;43:191–8.

Elsevier Foundation. Amref Health Africa—Leap. https://elsevierfoundation.org/partnerships/health-innovation/amref-health-africa-leap/. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

COVID-19 Digital Classroom. Quality-Assured COVID-19 Library of Resources for Community-Based Health Workers. https://covid-19digitalclassroom.org/. Accessed 18 Apr 2021.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the work of many colleagues in providing the case examples described in this paper.

Funding

Dr. Perry’s contribution as well as publication expenses were supported in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Investment ID OPP 1197181) and by the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) of Jhpiego, funded by the United States Agency for International Development. The funders had no role in the conduct of our work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HP defined the scope of this paper. MS wrote the first draft for the majority of the paper. IA drafted sections of the manuscript. MA and ZD contributed to the development of the boxes for the paper. All authors reviewed various drafts, and read and approved the final manuscript.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of Health Research Policy and Systems Volume 19, Supplement 3 2021: Community Health Workers at the Dawn of a New Era. The full contents of the supplement are available at https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-19-supplement-3.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All coauthors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schleiff, M.J., Aitken, I., Alam, M.A. et al. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 6. Recruitment, training, and continuing education. Health Res Policy Sys 19 (Suppl 3), 113 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00757-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00757-3