Abstract

Background

India’s accredited social health activist (ASHA) programme consists of almost one million female community health workers (CHWs). Launched in 2005, there is now an ASHA in almost every village and across many urban centres who support health system linkages and provide basic health education and care. This paper examines how the programme is seeking to address gender inequalities facing ASHAs, from the programme's policy origins to recent adaptations.

Methods

We reviewed all publically available government documents (n = 96) as well as published academic literature (n = 122) on the ASHA programme. We also drew from the embedded knowledge of this paper’s government-affiliated co-authors, triangulated with key informant interviews (n = 12). Data were analysed thematically through a gender lens.

Results

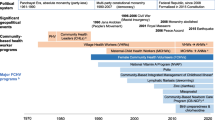

Given that the initial impetus for the ASHA programme was to address reproductive and child health issues, policymakers viewed volunteer female health workers embedded in communities as best positioned to engage with beneficiaries. From these instrumentalist origins, where the programme was designed to meet health system demands, policy evolved to consider how the health system could better support ASHAs. Policy reforms included an increase in the number and regularity of incentivized tasks, social security measures, and government scholarships for higher education. Residential trainings were initiated to build empowering knowledge and facilitate ASHA solidarity. ASHAs were designated as secretaries of their village health committees, encouraging them to move beyond an all-female sphere and increasing their role in accountability initiatives. Measures to address gender based violence were also recently recommended. Despite these well-intended reforms and the positive gains realized, ongoing tensions and challenges related to their gendered social and employment status remain, requiring continued policy attention and adaptation.

Conclusions

Gender trade offs and complexities are inherent to sustaining CHW programmes at scale within challenging contexts of patriarchal norms, health system hierarchies, federal governance structures, and evolving aspirations, capacities, and demands from female CHWs. Although still grappling with significant gender inequalities, policy adaptations have increased ASHAs’ access to income, knowledge, career progression, community leadership, and safety. Nonetheless, these transformative gains do not mark linear progress, but rather continued adaptations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The last decade has seen a resurgence of interest in national community health worker (CHW) programmes [1]. CHWs are paid or volunteer community members without professional degrees who are given basic training and work to improve health among their peers. CHWs have been positioned as an important element in partly overcoming the global health workforce shortage, thus enabling countries to achieve universal health coverage under Sustainable Development Goal 3 [2].

Within the recent flurry of attention towards CHWs, there has been little discussion of the gender considerations of these programmes. Yet every decision in designing, implementing and adapting CHW programmes has gendered implications: from deciding whose health to prioritize, which community members are selected with implications for livelihoods, safety, and job security, to (re)constructing gendered norms of caregiving and decision-making in families, communities, and healthcare systems. Although no comprehensive gender disaggregated data exists for CHW programmes, several countries have CHW programmes that are all-female by design. This is the case of the Lady Health Workers in Pakistan, the Women’s Development Army in Ethiopia, and India’s nearly one million-worker strong accredited social health activist (ASHA) programme (Table 1) [3].

Gender analysis in human resources for health highlights the overrepresentation of women as unpaid and often unrecognized carers for sick or elderly family members [4]. Within the paid health workforce, documented inequalities between male and female health workers in terms of pay, promotions, and employment security, and the higher rates workplace violence, including sexual violence, faced by female health workers remain pervasive [5,6,7]. With regard to CHWs in particular, studies have found that women generally prefer that CHWs who deliver reproductive, maternal, and child health interventions be female, because norms limit interaction between women and men who are not members of the same family. However, female CHWs are themselves limited by social norms constraining movement beyond the home and are vulnerable to critique and censure if they are seen to violate norms, such as by travelling outside the home at night or speaking to men [8]. Apart from the cross-cutting influence of social norms, gender dynamics influence CHWs at individual (family and intra-household relationships), community (safety and mobility), and health systems (remuneration and career progression) levels [9].

While the gender dimensions above refer to the technical content of CHW programmes, whether these dimensions are considered and how they are addressed enables one to categorize the extent to which a programme is gender responsive. Different terminologies exist ranging from gender blind, exploitative, accommodating, sensitive, specific, and transformative [10, 11]. Programmes can be considered gender blind if they ignore gender dimensions entirely, gender exploitative if they reinforce or take advantage of gender inequalities and stereotypes, gender accommodating if they address certain needs without changing the underlying inequalities that frame those needs, or gender transformative if they not only address needs, but transform the underlying power relations that maintain gender inequality [11].

Our analysis, conducted by internal programme leaders and external academic partners, takes into consideration published research, policy documents, and key informant interviews to explore the gendered design, evolution, and ongoing adaptations of the ASHA programme. In doing so, our objective is to reflect on the experience and challenges of addressing gender in large-scale CHW programmes that are a key but underappreciated foundation of health systems worldwide.

Methods

Data sources for this analysis consisted of all publically available government policy documents on the ASHA programme, all published academic literature on ASHAs, and key informant interviews with both governmental and non-government actors at the national and state levels. These key informant interviews served to triangulate the embedded and tacit knowledge of this paper’s government-affiliated co-authors (RV, GG, SS, AS), who have worked with the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare on the frontlines of developing and supporting the ASHA programme since its launch in 2005.

Government policy documents

We identified all national level government policy documents in the public sphere on the ASHA programme (n = 96) through targeted searches of relevant Government of India webpages. These documents included federal government memos to state governments, parliamentary committee reports, training guidelines, meeting minutes, and policy updates. All documents were downloaded in full and underwent data extraction. Appendix 1 presents the full list of included policy documents.

Academic literature review

We searched the electronic databases PubMed, Embase, and Scopus for articles published between 1 January 2005 and 15 August 2016. Searches were developed in consultation with an academic librarian and incorporated keywords and free text for the concepts ASHA (e.g. “accredited social health activist”, “community health worker”, “lay health worker”) under one string and India (e.g. India, “Arunachal Pradesh”, Assam, Bihar) under another string, with the two strings joined by the Boolean operator “AND”. See Appendix 2 for the full search strategy. Articles were excluded if it was not clear whether the CHW programme being discussed was the Government of India’s ASHA programme or if the article mentioned ASHAs only in passing. All primary research articles, abstracts, and commentaries on the ASHA programme were included (n = 122) and passed on to the data extraction phase (see the “Analysis” section) (Fig. 1).

Key informant interviews

We conducted 12 key informant (KI) interviews with Indian health system actors who had extensive involvement in shaping, designing, implementing, and adapting the ASHA programme. Key informants were senior policymakers in national- and state-level government and civil society actors. Interviews lasted an average of 1.5 h and were conducted face-to-face or over the telephone according to the convenience of the respondent. Respondents were invited to reflect upon the following areas: (a) stakeholder engagement in the ASHA policy process, including differing perspectives and agendas; (b) negotiations and tensions on policy content including ASHA roles and remit, incentives, selection criteria and process, training, and community orientation; (c) contextual influences; (d) threats and challenges that the programme has dealt with and speculation on potential future challenges; and (e) innovations and successes that can inform other large scale CHW programmes and future Indian policy processes.

Analysis

Analysis began with data extraction from the research articles and government policy documents using a framework of CHW-health system interfaces (CHW social profile and agency; CHW programme inputs; CHW-community interface; health services context; programme governance; programme outcomes; and programme impact). We then identified the health system components of the ASHA programme that emerged from the data as most pertinent to gender (remuneration, career progression/training, community recognition and relations, gender-based violence and safety) and triangulated them with key interviews. Finally, we mapped policy changes, academic findings, and stakeholder narratives together according to topic to identify and understand reasons for the programme’s features and their adaptation over time.

Results

We trace the evolution of the ASHA programme from its instrumentalist origins that focused on ASHAs as a tool to enable the health system meet its goals, to increasing attention to the empowering potential of the programme despite the challenges faced by the ASHAs. We then discuss the programme’s ongoing adaptations, as it strives to better meet ASHA needs for economic security, personal growth, and safety.

Instrumentalist origins

The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) (and later National Health Mission (NHM)), of which the ASHA programme was a cornerstone, focused particularly on maternal, newborn, and infant mortality, which were also receiving global attention through Millennium Development Goal 4 and 5 [12, 13] and population stabilization, which was of interest to government and external donors [14]: “First, in NRHM phase 1… we had Millennium Development Goals, so we also needed to reach there” (KI_02); “The donors… wanted to use her for population stabilisation and the link worker model, they wanted to push that” (KI_01). The government’s focus on addressing pressing reproductive, maternal, and child health needs was reflected in a number of key policy decisions for the ASHA programme (Table 2).

Forming an all-female cadre of CHWs was considered appropriate because maternal and child health were female spheres and women had high unmet reproductive health needs. Developing a cadre of female CHWs met women’s reproductive and maternal health needs in a culturally appropriate manner by having women speak to other women about these issues. At the same time, choosing only to have female CHWs worked within existing gendered norms of caregiving to address child health rather than challenging patriarchal norms that framed women as being primarily responsible for child care. In the following quotation, a policymaker (KI_04) justifies building an all-female cadre, saying that women are better at engaging other women and at influencing child health-related practices. Furthermore, she argues that women are less likely to shift into informal and unlicensed medical practice compared to men, suggesting that women are better at resisting corruption or falling into malpractice:

From the family and community perspective, [having] women [CHWs] has really helped in several ways. One is that they are able to much better reach out to women and children as opposed to men. The second is that they are prone to much less corruption than men…. Women relate much better to interact with women and children and also are less prone to doing private practice. One of the problems earlier [with a prior male CHW program] was that every male would [want] to become a [unlicensed] doctor and then would start practicing. (KI_04)

The decision that ASHAs would be volunteers who would earn small incentives for performing specific tasks was grounded in the government’s considerations of how best to meet population health needs in an affordable and sustainable manner appropriate for the federal governance structure in India. Some members of civil society were deeply concerned that the NHM did not create salaried government positions for ASHAs, and suggested that the voluntary nature of the position was only considered appropriate because ASHAs are women: “I would like to see nine lakh [900,000 – the approximate number of ASHAs at the time] men being treated like this” (KI_09).

However, policymakers cited a number of reasons why government actors argued that a salaried position was not feasible. First, they noted that administrative and monitoring structures in the rural health system were already strained and were struggling to ensure the selection, retention and performance of existing frontline health workers. They were concerned that ASHAs would underperform if guaranteed a salary, as was an ongoing challenge with child nutrition workers (called anganwadi workers) and frontline nurse-midwives.

So they [other policy actors] have a very strong opinion that if we change it, her performance will go down, she will become like another anganwadi worker. She’ll stop working. So that is also one of the arguments that comes across at all levels. So even some of the state nodal officers don’t want it, they say its fine, have performance based work. Increase the amount of incentives for each task that she does, make sure that she gets good amount of money. But they are not willing to change it to fixed paycheck because they are very worried that she will become another, like another anganwadi worker. And then who will monitor her? Because she is sitting somewhere in the village, and on a regular basis you can’t monitor her. (KI_07)

A lot of work gets done because … incentives make the person work (KI_02)

The person there knows that she will have to work. If she will not work she will not get paid (KI_06)

Second, national government actors in the Ministry of Finance were resistant to creating a large new cadre of government employees, who would be entitled to lifelong employment and pensions. The NHM was always supposed to be a mission, which would eventually strengthen state-level capacity to manage health in a decentralized manner:

It [NHM] was just envisaged as a temporary mission and we expected the states to be strengthened and to take ownership and then go forward, because I mean, it is a state subject and the responsibility is actually of the states for health. (KI_02)

Given India’s federal structure, the national government felt it was important that it be left to the states to decide on financing mechanisms themselves for the long term.

Third, some government actors noted that the flexibility built into the ASHA programme would be compromised by a salaried government position, since this would necessitate the application of rigid bureaucratic standards for eligibility, selection, leave, and ongoing employment. As a voluntary position, the educational requirement could be relaxed in highly marginalized areas and new women could be recruited to replace inactive ASHAs more easily. Finally, some civil society actors and government policymakers agreed that the intended community orientation of ASHAs could be compromised by a salaried employee model.

A genuine woman who wants to do something for the community will lose out, she will lose out on that opportunity. Because once you make it a government thing [a salaried formal position], then you will have… that exam, that process and application…. It will actually convert you into government. That lady would just say I am not kind of interested. So that woman who today, through that simple process become an ASHA, and also makes her name in the community… maybe tomorrow she will not be able to access that. (KI_06)

Very consciously, the institution of ASHA was seen as a community institution rather than a paid employee of the government. She was never intended to be the last member of the government health bureaucracy. It was on this account that a conscious decision was taken to provide only performance based payments to ASHAs. [15]

An implicit assumption underlying this latter rationalization is that a community orientation would inherently serve marginalized groups rather than be captured by community elites. Given the intersectional nature of ASHA profiles and the political economy of local communities, this assumption may not have always been valid.

Other key policy decisions that were taken to further community and health system goals included selecting local women and holding trainings close to the villages. ASHAs were to be married women, since women move to their husband’s villages upon marriage—unmarried women would likely leave their natal village upon marriage and were thus not preferred for ASHA selection [16]. Training close to the villages was also developed to increase the likelihood that ASHAs would attend the trainings.

Transformative potential and gendered challenges

Despite these instrumentalist origins, designing the programme for women and having it implemented by a female CHW cadre also created opportunities to empower women by elevating them in rural societies as role models and female leaders who spoke out about women’s rights [17,18,19]. Research studies document that becoming an ASHA enabled rural women to gain knowledge, status, and exposure beyond the village, as well as to access remuneration, albeit a limited amount [18,19,20,21,22]. ASHAs have reported an increased sense of empowerment and personal growth, in part through their belief in the social value of their work [18,19,20,21, 23,24,25,26,27]. Furthermore, ASHAs have worked to further women’s interests, particularly in Chhattisgarh state where Mitanins (the name for ASHAs there) have mobilized protests against alcoholism [23], supported women’s collectives and taken action against gender based violence [24].

Despite benefits derived from their work, ASHAs continue to face significant gendered challenges. Research findings have extensively documented ASHA worker dissatisfaction with their pay in relation to their workload and contribution and identified negative consequences linked to the limited remuneration structure [18, 20, 22, 26, 28,29,30,31,32,33]. Limitations on their movement outside the home and heavy domestic responsibilities often curtail ASHAs’ ability to perform their professional role [22, 28], and ASHA were discouraged from working and belittled by family members when their remuneration was delayed or when incentives were found to be extremely low [33]. Limited space for career progression is linked to low institutional recognition, demotivation, and curtailed opportunities for growth [19, 31, 34, 35]. ASHAs face sexual harassment by other health workers and community members, linked to their mobility and public profile [36]. In 2016, an ASHA was gang raped by community members and subsequently died, highlighting the extent of gender based violence and security concerns facing ASHAs [37].

In response to these issues, government health policy is engaged in ongoing efforts to improve ASHA wellbeing through increasing ASHA economic security, developing career progression strategies, and addressing gender based violence, as detailed below and in Table 3. While these policy changes are developed at the national level—with state level consultation—implementation varies widely according to state priorities.

Ongoing and unanticipated policy adaptations

Economic security

Policymakers have engaged creative strategies to meet ASHA calls for improved economic security despite the barriers to creating salaried positions for ASHAs and the Ministry of Finance’s resistance to fixed salaries [38] .Over time, the number of remunerated tasks and the amount of remuneration for each task steadily increased, from six remunerated tasks in 2005 to 38 in 2017 [39]. Social security measures were also introduced for ASHAs to access pensions and enrol in health insurance programmes [40, 41]. ASHA payments were shifted from cash to bank transfers, which reduced scope for skimming by higher level functionaries and brought ASHAs into the modern banking system [41]. In addition, the NHM identified a set of recurring monthly activities that ASHAs could perform to enable predictable remuneration that in some ways simulated a salary [42].

The impetus for these improvements can be traced to several sources. Some stakeholders expressed a prevailing sense that insufficient government expenditure on the programme was the ultimate impediment to ASHA empowerment: “We need to spend more money if we want to really empower them” (KI_03). In other key informant interviews, policy actors expressed their personal commitment to better meeting ASHA needs as a rights issue and in recognition for the increasingly important role that ASHAs have taken on in the Indian health system. For example:

Everyone I think, deep down, feels guilty that ASHAs need to be sort of compensated in a better way… everybody feels that they must do something. (KI_02)

Civil society activists and ASHAs themselves, with coordination through labour unions, have engaged in ongoing agitation and strikes for improved pay (KI_02, KI_06, KI_07, KI_09). The extent of political mobilization varies by state context. Others have noted that labour strikes have occurred in states where support structures had failed ASHAs:

Such protests are happening more in the states where the ASHA’s support structures are weak. You know where she thinks that nobody is really taking care of her, there is no mentor, ASHA facilitators are either not there or not doing the job that they should be doing. The system ownership is not there. This is more in states like [state 1], [state 2], where the support structures have been very weak. So in those states we see this happening a lot. I have not heard of a strike in [state 3] and [state 4]. The ASHAs get really small amounts of money but the investment in the program by the state is so much that, you know, that ASHAs feel part of, ASHAs feel taken care of. But in states like [state 5] where nothing else works for the ASHAs, even the trainings don’t happen for years, these kind of strikes are bound to happen. (KI_07).

Career aspirations and personal growth

Since 2012, government policymakers have added a number of features to the programme to better meet ASHA career aspirations and offer scope for greater personal growth. Residential training workshops with crèche facilities have been introduced so that ASHAs can experience immersive learning, develop empowering knowledge and skills, and build solidarity with other ASHAs [43]. The increasing scope of work and corresponding additional training is vital for addressing ASHA aspirations, including the acquisition of new personal and health-related skills [34]. In an effort to meet ASHA aspirations for career progression, the NHM has committed to paying tuition for all ASHAs seeking to complete secondary school education through the Open School System and to give ASHAs preferred admission to nursing and midwifery schools [44].

Community recognition and relations

Government policy has positioned ASHAs as member secretary of village health committees, thereby creating leadership opportunities in the village beyond the feminized-sphere of reproductive, maternal, and child health [45] (KI_01). While rigid gender norms make it difficult for many ASHAs to step into these roles, some communities have increasingly accepted the ASHA as meeting convener, public speaker, and activist on issues beyond reproductive, maternal and child health [24, 45]. This normative shift can be attributed to community recognition that the ASHA is following the government’s mandate as well as to training and support that has increased ASHA skills and confidence [45].

Safety and gender-based violence

Gender-based violence has been increasingly discussed by the national government as both an issue ASHAs can help address in their communities and as a threat to ASHAs themselves as they carry out their work [37, 46], particularly for lower caste ASHAs or ASHAs who transgress caste and other social hierarchies. Some ASHAs have begun taking action to mobilize their peers to reduce gender based violence [17]. The NHM sought to further support these efforts by developing a training module on the same topic [47]. ASHA safety has increasingly been prioritized with requirements that health facilities create safe overnight rest rooms for ASHAs who have accompanied patients, monthly staff meetings include discussion on sexual harassment, higher level staff take action in cases where threats or harassment are reported, all staff undergo training on violence against women, and grievance redressal systems be strengthened [46]. While these policy guidelines are issued at national level, it is up to states to implement them and for local managers and staff to adhere to them. They are important supportive steps, but they do not by themselves automatically change entrenched gender norms.

Discussion

The ASHA programme is now over 10 years old and just under one million women strong, placing it among the largest health worker cadres in the world. Similar to many CHW programmes, it started with instrumentalist concerns: deploying poor women in rural areas on a volunteer basis to address family planning, maternal and child health concerns. Measures to ensure that she was married locally and that training took place close to villages accommodated gender norms rather than challenged them. Over time, feedback and demands from multiple stakeholders, both within and outside the programme’s formal support structures, have led to efforts to address their marginalized status. Key efforts include improving their remuneration and benefits within fiscal and administrative constraints, supporting their ongoing training and career pathways, bolstering their community recognition and leadership potential, and most recently responding to security concerns and gender-based violence.

The value of community embeddedness for CHW programmes is widely recognized as a mechanism to ensure programme relevance to local needs and secure community ownership, support, and recognition of CHWs [48, 49]. CHW programmes seek to align CHWs with communities and many do so in part by recognizing that cultural norms make female CHWs more acceptable to reaching female beneficiaries [50, 51]. However, such recognition rarely problematizes power structures within communities, including the intersection of caste, marital status, class or age with gender [9]. Although ASHA demographics show adequate representation of all castes [17, 52], becoming an ASHA does not transform caste-based aspects of women’s identity. Lower caste ASHAs were often unable to visit higher caste homes and sometimes experienced discrimination from other health workers [31], and higher caste ASHAs avoided and at times disparaged lower caste areas [19, 28, 53,54,55] and these patterns of caste hierarchy among women are replicated across South Asia [19, 26, 56]. Older female CHWs may not be trusted by adolescents, while unmarried CHWs may not be accepted by older mothers [50]. More fundamentally, a gender transformative approach would seek to engage both men and women in changing conservative gender norms, rather than reaffirm conformity to them [57]. Ongoing research that critically engages with community power dynamics will enable CHW policy to maximize the benefits of community embeddedness while recognizing and responding to CHWs’ capacity to challenge or promote problematic norms related to caste, class or age.

The issue of remunerating female CHWs is also nuanced. The assumption that poor women can set aside time for volunteer work is deeply problematic [58], as are the structural barriers that often prevent their progression in the health workforce [9]. At the same time, this does not negate the fact that female CHWs, including ASHAs, are empowered by the exposure and social affirmation gained through their work, even if it entails juggling domestic responsibilities, livelihood demands and volunteer work [59, 60]. The former however does not preclude measures to support household recognition and sharing of domestic responsibilities and more secure economic security for women. The ASHA programme demonstrates the complexities involved in improving ASHA remuneration and benefits at scale in a federal health system.

Both Pakistan and Ethiopia’s CHW programmes, while being instrumentalist in nature, were also established through political decisions that framed the initiatives as employing and empowering women in rural areas. Despite the political backing behind these programmes and the ASHA programme, the extent and nature of that empowerment remains an open question. While gender theories put forward a linear view of moving from gender blindness to transformation, the ASHA programme demonstrates that change is not linear nor always anticipated. While some policy actors were conscious of how problematic the initial framing of the ASHA programme was, it was not until later that evidence and calls for reform enabled them put in place systems to respond. Finally, while policy guidelines supporting gender equality can be passed nationally, they do not result in transformation if they are not owned and championed by local actors.

Particularly telling is the scepticism by some stakeholders about the ASHAs’ political mobilization and demands for higher pay, revealing gendered assumptions that female CHWs ought to display an inherently altruistic, acquiescent, and apolitical nature. The ASHAs’ political mobilization has gone against the narrative of selfless women, invested in the wellbeing of children and their communities at the expense of themselves. ASHAs have demonstrated agency in seeking more income, as well as courageously standing up for women’s rights in the face of pervasively conservative gender norms. Their agency to voice their demands illustrates that, regardless of whether a programme is instrumentalist or transformative in nature, more powerful actors cannot predict what female CHWs will do as increasingly empowered agents of change.

Conclusions

This analysis identified the gender trade offs and complexities inherent to developing and sustaining a CHW programme at scale within a challenging context of patriarchal norms, health system hierarchies, federal governance structures, and rapidly evolving aspirations, capacities, and demands from female CHWs and the communities in which they reside. While the ASHA programme has consciously tried to move past its instrumentalist origins, continual adaptations are required to address ongoing gender challenges, both anticipated and unanticipated. These reforms, while imperfect due to the complexities faced, do chart progress and highlight the investments and responsive planning required to support gender transformation in CHW programmes.

Abbreviations

- ASHA:

-

Accredited social health activist

- CHW:

-

Community health worker

- KI:

-

Key informant

- NHM:

-

National Health Mission

- NRHM:

-

National Rural Health Mission

References

Schneider H, Okello D, Lehmann U. The global pendulum swing towards community health workers in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review of trends, geographical distribution and programmatic orientations, 2005 to 2014. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14(1):65.

Maher D, Cometto G. Research on community-based health workers is needed to achieve the sustainable development goals. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(11):786.

NHSRC. Update on ASHA programme, January. New Delhi; 2017. Available from: http://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/Update%20on%20ASHA%20Programme-%20January-2017.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr 2017.

George A. Nurses, community health workers, and home carers: gendered human resources compensating for skewed health systems. Glob Public Health. 2008;3(Suppl 1):75–89.

George AS. Human resources for health: a gender analysis. Review Paper prepared for the Women and Gender Equity, and Health Systems, Knowledge Networks Networks (KNs) of the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. 2007. Available from: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/human_resources_for_health_wgkn_2007.pdf.

Standing H. Gender - a missing dimension in human resource policy and planning for health reforms. Hum Resour Heal Dev J. 2000;4(1):27–42.

Newman CJ. Time to address gender discrimination and inequality in the health workforce. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12(1):25.

Kok MC, Kane S, Tulloch O, Ormel H, Theobald S, Dieleman M, et al. How does context influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? Evidence from the literature. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2015;13(1):13.

Steege R, Taegtmeyer M, McCollum R, Hawkins K, Ormel H, Kok M, et al. How do gender relations affect the working lives of close to community health service providers? Empirical research, a review and conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2018;209(April):1–13.

WHO. WHO Gender Mainstreaming Manual for Health Managers: a practical approach [Internet]. Geneva; 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/health_managers_guide/en. Accessed 30 Jan 2018.

USAID/PACE/IGWA. The gender integration continuum. Washington, DC: USAID; 2017.

Bajpai N, Sachs JD, Dholakia RH. Improving access, service delivery and efficiency of the public health system in rural India: Mid-term evaluation of the National Rural Health Mission. Vol. No. 37, CGSD Working Papers. New York: Center on Globalization and Sustainable Development; The Earth Institute at Columbia University; 2009.

MoHFW. Guidelines for antenatal care and skilled attendance at birth by ANMs/LHVs/SNs. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2010.

MoHFW India. National Rural Health Mission (2005–2012): Mission Document [Internet]. New Delhi; 2005. Available from: http://www.nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/about-nrhm/nrhm-framework-implementation/nrhm-framework-latest.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr 2017.

NRHM. Letter from GC Chaturvedi, Additional Secretary and Mission Director (NRHM), Subject: Performance based payment to ASHAs. D.O. No A. 11033/61/2007-Trg. Letter dated 19th Sept 2008. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2008.

MoHFW India. ASHA Guidelines. New Delhi: National Rural Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2006.

NHSRC. ASHA: which way forward? Evaluation of the ASHA Programme. Mission NRH, editor. New Delhi: National Health Systems Resource Centre; 2011.

Gopalan SS, Mohanty S, Das A. Assessing community health workers’ performance motivation: a mixed-methods approach on India’s Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) programme. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5):e001557.

Roalkvam S. Health governance in India: citizenship as situated practice. Glob Public Health. 2014;9(8):910–26.

Scott K, Shanker S. Tying their hands? Institutional obstacles to the success of the ASHA community health worker programme in rural North India. AIDS Care. 2010;22(Suppl 2):1606–12.

Pandey J, Singh M. Donning the mask: effects of emotional labour strategies on burnout and job satisfaction in community healthcare. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(5):551–62.

Saprii L, Richards E, Kokho P, Theobald S, Greenspan J, McMahon S, et al. Community health workers in rural India: analysing the opportunities and challenges accredited social health activists (ASHAs) face in realising their multiple roles. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1):95.

Sundararaman T. Community health-workers: scaling up programmes. Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2058–9.

Nandi S, Schneider H. Addressing the social determinants of health: a case study from the Mitanin (community health worker) programme in India. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:ii71–81.

Deshpande S, Bhanot A, Maknikar S. Assessing the influence of a 360-degree marketing communications campaign with 360-degree feedback. Soc Mark Q. 2015;21(3):142–51.

Srivastava D, Prakash S, Ashish V, Nair K, Gupta S, Nandan DA. Study of Interface of ASHA with the community and the service providers in eastern Uttar Pradesh. Indian J Public Health. 2009;53(3):133.

Shukla A, Bhatnagar T. Accredited social health activists and pregnancy related services in Uttarakhand, India. BMC Proc. 2012;6(Suppl 1):1–2.

Pala S, Kumar D, Jeyashree K, Singh A. Preliminary evaluation of the ASHA scheme in Naraingarh block, Haryana. Natl Med J India. 2011;24(5):315–6.

Mahanta TG, Islam S, Sudke AK, Kumari V, Gogoi P, Rane T, et al. Effectiveness of introducing home-based newborn care (HBNC) voucher system in Golaghat District of Assam. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal. 2016;4(2):69–75.

Praveen D, Patel A, Raghu A, Clifford GD, Maulik PK, Mohammad Abdul A, et al. SMARTHealth India: development and field evaluation of a mobile clinical decision support system for cardiovascular diseases in rural India. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2014;2(4):e54.

Sharma R, Webster P, Bhattacharyya S. Factors affecting the performance of community health workers in India: a multi-stakeholder perspective. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):1–8.

Gopalan SS, Durairaj V. Addressing maternal healthcare through demand side financial incentives: experience of Janani Suraksha Yojana program in India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):319.

Bhatia K. Performance based incentives of the ASHA scheme: stakeholders’ perspectives. Econ Polit Wkly. 2014;49(22):145.

Bhatia K. Community health worker programs in India: a rights-based review. Perspect Public Health. 2014;134(5):276–82.

Nambiar D, Sheikh K, Verma N. Scale-up of community action for health: lessons from a realistic evaluation of the Mitanin program in Chhattisgarh, India. BMC Proc 2012;6; 5(Suppl 5):026.

Dasgupta J, Velankar J, Borah P, Nath GH. The safety of women health workers at the frontlines. Indian J Med Ethics. 2017;2(3):209–13.

Gangotri, Pritisha, Bhargava R, Rehana Adib, Velankar J, Dasgupta J. Report of independent fact-finding into the incident of gang-rape and death of an ASHA worker Somwati Tyagi in Muzaffarnagar District, Uttar Pradesh, India. National Alliance for Maternal Health and Human Rights & Healthwatch Forum Uttar Pradesh. 2016.

Ministry of Finance. Payment of monthly honorarium @ Rs.500, to ASHA in addition to performance incentives available under various programmes, no. 17(10)/PF-II/2004(Vol. IV); 13/04/2009. New Delhi: Ministry of Finance, Government of India; 2009.

MoHFW India. Letter from the principal secretary (health and family welfare) to the states and UTs. Revision of financial norms for implementing UIP-MSG, T.13011/01/2012-CC&V, 25/05/2012. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2012.

NRHM. Old age income security proposed for ASHA under National Pension System, Swavalamban scheme, D.O. no. 7(205)/2012-NRHM.I, 04/09/2012. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2012.

NRHM. Implementation of recommendations of parliamentary committee on working conditions of ASHA, DO no. H-11014(2)/2010-NRHM-I, 15/02/2011. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2011.

NRHM. Letter from additional Secretary & Mission Director (NRHM) to states, incentive to ASHAs for Routine & Recurring Activities - MSG approval, D. O. no. P17018/14/13-NRHM-IV, 03/01/2014. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2014.

NHM. Guidelines for accreditation of training sites and trainers for ASHA training under the National Health Mission, 18/05/2015. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2015.

NRHM. Career progression for the ASHA, D.O. no. Z28014/1/13-NRHM-IV, 18/09/2013. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2013.

Scott K, George AS, Harvey SA, Mondal S, Patel G, Sheikh K. Negotiating power relations, gender equality, and collective agency: are village health committees transformative social spaces in northern India? Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:84.

NHM. Safety measures for ASHAs, D. O. no. 7(12)/2016-NRHM-I, 09/01/2016. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2016.

NHM. Mobilizing for action on violence against women. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2016.

Schneider H, Lehmann U. From community health workers to community health systems: time to widen the horizon? Heal Syst Reform. 2016;2(2):112–8.

Scott K, Beckham S, Gross M, Pariyo G, Rao K, Cometto G, et al. What do we know about community-based health programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers and their integration with health systems. Hum Resour Health. 2018:1–17.

Feldhaus I, Silverman M, Lefevre AE, Mpembeni R, Mosha I, Chitama D, et al. Equally able, but unequally accepted: gender differentials and experiences of community health volunteers promoting maternal, newborn, and child health in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. Int J Equity Health. 2015:1–11.

Viswanathan K, Hansen P, Rahman M, Steinhardt L, Edward A, Arwal S. Can community health workers increase coverage of reproductive health services? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:894–900.

Kohli C, Kishore J, Sharma S, Nayak H. Knowledge and practice of accredited social health activists for maternal healthcare delivery in Delhi. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2015;4(3):359–63.

Mishra A. ‘Trust and teamwork matter’: community health workers’ experiences in integrated service delivery in India. Glob Public Heal An Int J Res Policy Pract. 2014;9(8):960–74.

Nordfeldt C, Roalkvam S. Choosing vaccination: negotiating child protection and good citizenship in modern India. Forum Dev Stud. 2010;37(3):327–47.

Parveen K. Performance evaluation of community health workers during CCSP training programme. Indian J Public Heal Res Dev. 2016;7(1):91–4.

Mumtaz Z, Salway S, Waseem M, Umer N. Gender-based barriers to primary health care provision in Pakistan: the experience of female providers. Health Policy Plan. 2003;18(3):261–9.

Portella A, Gouveia T. Social health policies: a question of gender? The case of community health agents from Camaragibe municipality. Recife: SOS CORPO; 1997.

Maes K, Closser S, Vorel E, Tesfaye Y. Using community health workers: discipline and hierarchy in Ethiopia’s women’s development Army. Ann Anthropol Pract. 2015;39(1):42–57.

Daniels K, Van Zyl H, Clarke M, Dick J, Johansson E. Ear to the ground: listening to farm dwellers talk about the experience of becoming lay health workers. Health Policy (New York). 2005;73:92–103.

Glenton C, Scheel IB, Pradhan S, Lewin S, Hodgins S. The female community health volunteer programme in Nepal: decision makers’ perceptions of volunteerism, payment and other incentives. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(12):1920–7.

Health Survey and Development Committee. Report of the national health survey and development committee (Bhore Committee Report). New Delhi; 1946. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/sites/default/files/pdf/Bhore_Committee_Report_VOL-1.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2017.

MoHFW India. Srivastava committee report: health services and medical education: a program for immediate action. Bombay: Indian Council of Social Science Research; 1975.

Leslie C. What caused India’s massive community health workers scheme: a sociology of knowledge. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21(8):923–30.

MoHFW India, MoHFW. National rural health mission: framework for implementation (2005–2012) [Internet]. New Delhi; 2005. Available from: http://www.nipccd-earchive.wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/PDF/NRHM%20-%20Framework%20for%20Implementation%20-%20%202005-MOHFW.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2017.

National Health Mission. Minutes of 5th Meeting of the Mission Steering Group, National Health Mission, February, 2018. New Delhi; 2018. Available from: http://nhm.gov.in/New_Updates_2018/Monitoring/MSG/5th-MSG-of-NHM-Minutes.pdf. Accessed 5 Mar 2018.

National Health Mission. Minutes of 4th Meeting of the Mission Steering Group, National Health Mission, January, 2017. New Delhi; 2017. Available from: http://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/monitoring/mission-steering-group/Minutes_of_4th_MSG_of_NHM.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2017.

MoHFW India. Guidelines for community processes. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2013.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all key informants for sharing their time and insights.

Role of funding sources

The funding sources had no role in any aspect pertinent to the study, including the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of results. No pharmaceutical companies or other commercial agencies paid us to write this article. All authors including KS the corresponding author have full access to the data in the study.

Funding

This research was made possible in part by funding received from the South African Research Chair in Health Systems, Complexity and Social Change supported by the South African Research Chair’s Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant No 82769). Any opinion, finding and conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the author and the National Research Foundation does not accept any liability in this regard.

This research was made possible in part by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development, under the terms of the Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-14-00028. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

Availability of data and materials

Portions of the qualitative transcripts used and analysed during the current study can be provided from the corresponding author on reasonable request. However, only sections will be made available and only after editing has removed all potentially identifying details. The government policy documents analysed are publically available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RV and ASG conceptualized the study and designed it with support from KS and GG. Government policy documents were collated by OU, GG, SS, and AS with support from RV. Primary key informant interview data was collected by ASG and KS. KS conducted the literature review with support from ASG. Data extraction was conducted by KS, OU, and ASG. Analysis was conducted by ASG, KS, and RV; GG, SS, OU, and AS supported interpretation of results. The full manuscript was drafted by KS and ASG, with input from all other authors. All authors reviewed and agreed to the analyses, results interpretation, and write up of the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Biomedical Science Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Western Cape, South Africa, approved the key informant interviews (reference number: BM17/6/18, rec number REC 130416-050). Our analysis of publically available government policy documents and published academic work are not human subject research. All participants provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

RV, GG, SS, and AS are employees of the National Health Systems Resource Centre, which is a technical support agency for the National Rural Health Mission, under the Government of India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Literature search strategy

PubMed

Search concept #1: ASHA community health worker

}mitanin} OR}Mitanin} OR}sahyogini} OR}Sahyogini} OR}ASHA} or}Accredited Social Health Activist} OR}accredited social health activist} OR}health auxiliary} OR}frontline health workers} OR}frontline health worker} OR}outreach worker} OR}outreach workers} OR}lay health worker} OR}lay health workers} OR}village health worker} OR}village health workers} OR}volunteer health worker} OR}volunteer health workers} OR}voluntary health workers} OR}voluntary health worker} OR}community health agent} OR}community health agents} OR}health promoter} OR}health promoters} OR}Community Health Workers}[Mesh] OR}community health worker} OR}community health workers} OR}community health aide} OR}community health aides} OR}community health volunteer} OR}community health volunteers} OR}community health assistants} OR}community health assistant} OR}community health promoters} OR}community health promoters} OR}community volunteer} OR}community volunteers} OR}health extension workers} OR}health extension worker} OR}village health volunteer} OR}village health volunteers} OR}Community Health Nursing}[Mesh] OR}close-to-community provider} OR}close-to-community providers} OR}community-based practitioner} OR}community-based practitioners} OR}Community Practitioners} OR}Community Practitioner} OR}community-based practitioners} OR}community-based practitioner} OR}rural health auxiliaries} OR}Basic health worker} OR}Basic health workers} OR}Community health agent} OR}Community health agents} OR}Community health promoter} OR}Community health promoters} OR}Community health representative} OR}Community health representatives} OR}Community health volunteer} OR}Community health volunteers} OR}Community resource person} OR}Female multipurpose health worker} OR}Female multipurpose health worker} OR}Health promoter} OR}Health promoters} OR}Outreach educator} OR}Outreach educators} OR}Sevika} OR}Village health helper} OR}Community Case Management Workers} OR}Community Health Agent} OR}Community Health Agents} OR}Community Health Care Provider} OR}Community Health Care Providers} OR}Community HealthCare Provider} OR}Community HealthCare Providers} OR}Cxommunity Health Extension Worker} OR}Community Health Extension Workers} OR}Family Health Worker} OR}Family Health Workers} OR}Family Planning Agent} OR}Family Planning Agents} OR}Family Welfare Assistant} OR}Family Welfare Assistants} OR}Female Community Health Volunteer} OR}Female Community Health Volunteers} OR}Health Agent} OR}Health Agents} OR}Health Assistant} OR}Health Assistants} OR}Maternal and Child Health Worker} OR}Maternal and Child Health Workers} OR}Peer Educator} OR}Peer Educators}.

Search concept #2: India

India[mesh] OR Indian[tiab] OR}Andhra Pradesh} [tiab] OR}Arunachal Pradesh} [tiab] OR Assam[tiab] OR Bihar[tiab] OR Chhattisgarh[tiab] OR Goa[tiab] OR Gujarat[tiab] OR Haryana[tiab] OR}Himachal Pradesh} [tiab] OR Jammu[tiab] OR Kashmir[tiab] OR Jharkhand[tiab] OR Karnataka[tiab] OR Kerala[tiab] OR}Madhya Pradesh} [tiab] OR Maharashtra[tiab] OR Manipur[tiab] OR Meghalaya[tiab] OR Mizoram[tiab] OR Nagaland[tiab] OR Odisha[tiab] OR Orissa[tiab] OR Punjab[tiab] OR Rajasthan[tiab] OR Sikkim[tiab] OR}Tamil Nadu} [tiab] OR Telangana[tiab] OR Tripura[tiab] OR}Uttar Pradesh} [tiab] OR Uttarakhand[tiab] OR}West Bengal} [tiab] OR Andaman[tiab] OR Nicobar[tiab] OR Chandigarh[tiab] OR Dadra[tiab] OR}Nagar Haveli} [tiab] OR Daman[tiab] OR Diu[tiab] OR Lakshadweep[tiab] OR Delhi[tiab] OR Puducherry[tiab] OR Pondicherry[tiab].

EMBASE

Search concept #1: ASHA community health worker

}mitanin} OR}Mitanin} OR}sahyogini} OR}Sahyogini} OR}ASHA} or}Accredited Social Health Activist} OR}accredited social health activist} OR ‘health auxiliary’/exp. OR}health auxiliary} OR}frontline health workers} OR}frontline health worker} OR}outreach worker} OR}outreach workers} OR}lay health worker} OR}lay health workers} OR}village health worker} OR}village health workers} OR}volunteer health worker} OR}volunteer health workers} OR}voluntary health workers} OR}voluntary health worker} OR}community health agent} OR}community health agents} OR}health promoter} OR}health promoters} OR}Community Health Workers} OR}community health worker} OR}community health workers} OR}community health aide} OR}community health aides} OR}community health volunteer} OR}community health volunteers} OR}community health assistants} OR}community health assistant} OR}community health promoters} OR}community health promoters} OR}community volunteer} OR}community volunteers} OR}health extension workers} OR}health extension worker} OR}village health volunteer} OR}village health volunteers} OR}Community Health Nursing} OR}Community Health Nursing}/exp. OR}close-to-community provider} OR}close-to-community providers} OR}community-based practitioner} OR}community-based practitioners} OR}Community Practitioners} OR}Community Practitioner} OR}community-based practitioners} OR}community-based practitioner} OR}rural health auxiliaries} OR}Basic health worker} OR}Basic health workers} OR}Community health agent} OR}Community health agents} OR}Community health promoter} OR}Community health promoters} OR}Community health representative} OR}Community health representatives} OR}Community health volunteer} OR}Community health volunteers} OR}Community resource person} OR}Female multipurpose health worker} OR}Female multipurpose health worker} OR}Health promoter} OR}Health promoters} OR}Outreach educator} OR}Outreach educators} OR}Sevika} OR}Village health helper} OR}Community Case Management Workers} OR}Community Health Agent} OR}Community Health Agents} OR}Community Health Care Provider} OR}Community Health Care Providers} OR}Community HealthCare Provider} OR}Community HealthCare Providers} OR}Community Health Extension Worker} OR}Community Health Extension Workers} OR}Family Health Worker} OR}Family Health Workers} OR}Family Planning Agent} OR}Family Planning Agents} OR}Family Welfare Assistant} OR}Family Welfare Assistants} OR}Female Community Health Volunteer} OR}Female Community Health Volunteers} OR}Health Agent} OR}Health Agents} OR}Health Assistant} OR}Health Assistants} OR}Maternal and Child Health Worker} OR}Maternal and Child Health Workers} OR}Peer Educator} OR}Peer Educators}.

Search concept #2: India

India/exp. OR (India OR Indian OR}Andhra Pradesh} OR}Arunachal Pradesh} OR Assam OR Bihar OR Chhattisgarh OR Goa OR Gujarat OR Haryana OR}Himachal Pradesh} OR Jammu OR Kashmir OR Jharkhand OR Karnataka OR Kerala OR}Madhya Pradesh} OR Maharashtra OR Manipur OR Meghalaya OR Mizoram OR Nagaland OR Odisha OR Orissa OR Punjab OR Rajasthan OR Sikkim OR}Tamil Nadu} OR Telangana OR Tripura OR}Uttar Pradesh} OR Uttarakhand OR}West Bengal} OR Andaman OR Nicobar OR Chandigarh OR Dadra OR}Nagar Haveli} OR Daman OR Diu OR Lakshadweep OR Delhi OR Puducherry OR Pondicherry):ab,ti.

Scopus

Search concept #1: ASHA community health worker

{mitanin} OR {Mitanin} OR {sahyogini} OR {Sahyogini} OR {ASHA} or {Accredited Social Health Activist} OR {accredited social health activist} OR ‘health auxiliary’/exp. OR {health auxiliary} OR {frontline health workers} OR {frontline health worker} OR {outreach worker} OR {outreach workers} OR {lay health worker} OR {lay health workers} OR {village health worker} OR {village health workers} OR {volunteer health worker} OR {volunteer health workers} OR {voluntary health workers} OR {voluntary health worker} OR {community health agent} OR {community health agents} OR {health promoter} OR {health promoters} OR {Community Health Workers} OR {community health worker} OR {community health workers} OR {community health aide} OR {community health aides} OR {community health volunteer} OR {community health volunteers} OR {community health assistants} OR {community health assistant} OR {community health promoters} OR {community health promoters} OR {community volunteer} OR {community volunteers} OR {health extension workers} OR {health extension worker} OR {village health volunteer} OR {village health volunteers} OR {Community Health Nursing} OR {Community Health Nursing}/exp. OR {close-to-community provider} OR {close-to-community providers} OR {community-based practitioner} OR {community-based practitioners} OR {Community Practitioners} OR {Community Practitioner} OR {community-based practitioners} OR {community-based practitioner} OR {rural health auxiliaries} OR {Basic health worker} OR {Basic health workers} OR {Community health agent} OR {Community health agents} OR {Community health promoter} OR {Community health promoters} OR {Community health representative} OR {Community health representatives} OR {Community health volunteer} OR {Community health volunteers} OR {Community resource person} OR {Female multipurpose health worker} OR {Female multipurpose health worker} OR {Health promoter} OR {Health promoters} OR {Outreach educator} OR {Outreach educators} OR {Sevika} OR {Village health helper} OR {Community Case Management Workers} OR {Community Health Agent} OR {Community Health Agents} OR {Community Health Care Provider} OR {Community Health Care Providers} OR {Community HealthCare Provider} OR {Community HealthCare Providers} OR {Community Health Extension Worker} OR {Community Health Extension Workers} OR {Family Health Worker} OR {Family Health Workers} OR {Family Planning Agent} OR {Family Planning Agents} OR {Family Welfare Assistant} OR {Family Welfare Assistants} OR {Female Community Health Volunteer} OR {Female Community Health Volunteers} OR {Health Agent} OR {Health Agents} OR {Health Assistant} OR {Health Assistants} OR {Maternal and Child Health Worker} OR {Maternal and Child Health Workers} OR {Peer Educator} OR {Peer Educators}.

Search concept #2: India

TITLE-ABS({India} OR {Indian} OR {Andhra Pradesh} OR {Arunachal Pradesh} OR {Assam} OR {Bihar} OR {Chhattisgarh} OR {Goa} OR {Gujarat} OR {Haryana} OR {Himachal Pradesh} OR {Jammu} OR {Kashmir} OR {Jharkhand} OR {Karnataka} OR {Kerala} OR {Madhya Pradesh} OR {Maharashtra} OR {Manipur} OR {Meghalaya} OR {Mizoram} OR {Nagaland} OR {Odisha} OR {Orissa} OR {Punjab} OR {Rajasthan} OR {Sikkim} OR {Tamil Nadu} OR {Telangana} OR {Tripura} OR {Uttar Pradesh} OR {Uttarakhand} OR {West Bengal} OR {Andaman} OR {Nicobar} OR {Chandigarh} OR {Dadra} OR {Nagar Haveli} OR {Daman} OR {Diu} OR {Lakshadweep} OR {Delhi} OR {Puducherry} OR {Pondicherry}).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ved, R., Scott, K., Gupta, G. et al. How are gender inequalities facing India’s one million ASHAs being addressed? Policy origins and adaptations for the world’s largest all-female community health worker programme. Hum Resour Health 17, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0338-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0338-0