Abstract

Background

The liver is a major target organ for metastases of various types of cancers. Surgery is a well-established option for colorectal liver metastases (CRLM). Regarding the improved surgical and anesthetic techniques, the safety of liver resection has increased. Consequently, the interest in the surgical management of non-colorectal liver metastases (non-CRLM) has gained significant attention. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the surgical treatment outcomes for non-CRLM and to compare it with an outcome of CRLM in a tertiary care center in the Baltic country—Lithuania.

Methods

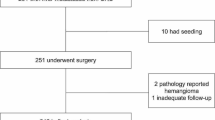

We retrospectively analyzed data from all patients who underwent liver resection for CRLM or non-CRLM between 2010 and 2017 in a tertiary care center—Vilnius University hospital Santaros Clinics. Demographic and metastasis characteristics, as well as disease-free and overall survival, were compared between the study groups.

Results

In total, 149 patients were included in the study. Patients in the CRLM group were older (63.2 ± 1.01 vs 54.1 ± 1.8 years, p < 0.001) and mainly predominant by males. Overall postoperative morbidity rate (16.3% vs 9.8%, p = 0.402) and major complications rate (10% vs 7.8%, p = 0.704) after liver resection for CRLM and non-CRLM was similar. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed higher disease-free survival in the CRLM group with 89.4% vs 76.5% and 64.9% vs 31.4% survival rates at 1 and 3 years, respectively (p = 0.042), although overall survival was not different between the CRLM and non-CRLM groups with 89.4% vs 78.4% and 72.0% vs 46.1% survival rates at 1 and 3 years, respectively (p = 0.300).

Conclusions

In this study, we confirmed comparable short- and long-term outcomes after liver resection for CRLM and non-CRLM. Surgical resection should be encouraged as an option in well-selected patients with non-CRLM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The liver is a major target organ for metastases of various types of cancer. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide [1, 2] and about 50% of CRC patients will develop colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) throughout their course of disease [3, 4]. Surgery for CRLM is well defined by current guidelines, and it is the only treatment method that may be potentially curative. In contrast, the therapeutic approaches for non-colorectal liver metastases (non-CRLM) remain controversial. Due to the wide heterogeneity of origin, the different biological behavior of different cancers, and the relatively lower incidence, there are no strict guidelines on how to manage non-CRLM. Systemic treatment for non-CRLM is available, although it does not offer satisfactory results, with survival for only a few months [5]. Regarding, the improved surgical and anesthetic techniques, the safety of liver resection has improved over the last decades [5]. Consequently, the interest in the surgical management of non-CRLM has gained significant attention, although the surgery for non-CRLM remains non-standardized. Thus, there is a need for studies investigating short- and long-term outcomes after liver resection for non-CRLM. Moreover, the outcomes of liver surgery strongly depend on a surgeon and a hospital volume [6]. While the centralization of liver surgery in large and well-developed countries is feasible, it may remain challenging in smaller or developing countries. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the outcomes of surgery for non-CRLM and to compare it with outcomes after liver resection for CRLM in a tertiary care center in the Baltic country—Lithuania.

Materials and methods

Ethics

Vilnius regional biomedical research ethics committee approval (No. 158200-18/7-1054-553) was obtained before this study was conducted. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion criteria

All patients who underwent liver resection for CRLM or non-CRLM between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2017, at a tertiary care center—Vilnius University hospital Santaros Clinics—were included in the study. In all cases, surgical resection was performed after patients were discussed at a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Data collection

Data on patient characteristics were extracted from the prospectively collected institutional electronic database. They included age; gender; the history of previous cancer treatment; origin, number, and size of metastases; surgical approach (open surgery, laparoscopic surgery); and intraoperative data such as length of surgery, blood loss, and postoperative complications by Clavien-Dindo classification.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was overall survival (OS). The secondary outcomes included disease-free survival (DFS) and postoperative morbidity. OS was defined as the time from liver resection to death. Data on survival and date of death were collected from the National Lithuanian Cancer registry. DFS was defined as the time from surgery to disease progression including local or distant recurrence.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical program SPSS 24.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation or median with an interquartile range where appropriate. Categorical variables are shown as proportions. Continuous variables were compared by a t test or ANOVA, and categorical variables by the Pearson’s chi-square test. Overall and recurrence-free survival rates were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Statistical significance was considered when p value < 0.05 was achieved.

Results

Baseline characteristics

In total, 149 patients were included in the study. Based on the origin of the metastases, 98 (65.7%) were allocated to CRLM and 51 (34.2%) to the non-CRLM group. The baseline clinicopathological characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients in the CRLM group were older (63.2 ± 1.01 vs 54.1 ± 1.8 years, p < 0.001) and mainly predominant by males, while in the non-CRLM group by females (60/38 vs 11/40, p < 0.001).

Liver metastasis

In the CRLM group, the most common origin of metastases was sigmoid and rectal cancer (52.0%) while in the non-CRLM group gynecological and neuroendocrine tumors (43.1%) (Fig. 1). Metachronous metastases accounted for 86.7% and 94.7% in the CRLM and non-CRLM groups, respectively, p < 0.171. The mean number (2.3 ± 2.0 vs 2.4 ± 2.5, p = 0.706) and size (3.0 ± 2.7 vs 3.0 ± 3.6 cm, p = 0.984) of metastases were not different between the CRLM and non-CRLM groups (Table 2).

Surgery and short-term outcomes

Atypical resection was dominating surgical intervention accounting for 77.8% of all operations. In the CRLM group, 31 (31.6%) patients underwent combined surgical intervention of resection and radiofrequency ablation. There were no differences between the CRLM and non-CRLM groups regarding operation time, intraoperative blood loss, and postoperative blood transfusions (Table 3). Overall postoperative morbidity rate was similar between the CRLM and non-CRLM groups (16.3% vs 9.8%, p = 0.402). Major complications by the Clavien-Dindo III-IV rate were similar (10% vs 7.8%, p = 0.704) as well. The most common complications were postoperative hematomas, biliomas, and intraabdominal abscesses. One (1.0%) patient from CRLM died after surgery, while all patients in the non-CRLM group were successfully discharged from the hospital.

Long-term outcomes

The median time to follow-up was 38 (Q1;Q3, 22;55) months. Four (2.6%) patients were lost to follow-up. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed higher DFS in the CRLM group with 89.4% vs 76.5% and 64.9% vs 31.4% survival rates at 1 and 3 years, respectively (p = 0.042) (Fig. 2a), although OS was not different between the CRLM and non-CRLM groups with 89.4% vs 78.4% and 72.0% vs 46.1% survival rates at 1 and 3 years, respectively (p = 0.300) (Fig. 2b).

Discussion

Liver resection remains the only potentially curative option for patients with liver metastasis. Resection is a well-established option for CRLM; however, its role for non-CRLM remains controversial because of invasiveness and unclear oncological benefits, although continuously improving surgical techniques, better intensive care, and modern chemotherapeutic regimens made liver resection safer and more acceptable option [7]. Thus, patients with non-CRLM may also be considered for radical surgery nowadays.

The present study confirmed similar safety of liver resection for CRLM and non-CRLM. Our findings are consistent with some previous reports suggesting satisfactory short-term outcomes in patients with non-CRLM since the modern and standardized operation techniques are adopted [8,9,10,11]. Liver surgery changed in the past 20–30 years after resections became refined, and with an accumulation of evidence, liver parenchyma-sparing techniques, such as atypical resections for metastases, became dominant to preserve liver volume and function [12]. In our cohort, most of all resections were atypical and major resections were limited to cases with multiple lesions in the single lobe. With increasing trends of laparoscopic approach in modern liver surgery, we also incorporated it into our clinical practice, because the laparoscopic approach has been proven to be not inferior to open liver resection in terms of safety and oncological outcomes including surgery for non-CRLM [9, 13,14,15].

Further, our study showed comparable long-term outcomes after liver resection for CRLM or non-CRLM. Nowadays, the reported 5-year OS rate for CRLM exceeds 50% [7, 16] and similar outcomes were achieved in our study. In contrast, the reported OS rate for non-CRLM varies between 5 and 50% [17,18,19,20,21,22], and such differences exist because of high heterogeneity for a different type of tumors in this group of patients. In our cohort, the majority of CRLM originated from the left side colon and rectum, which is typically a more common origin for liver metastasis compared to the right colon [2]. Our non-CRLM group was heterogeneous, but most metastases originated from gynecological and neuroendocrine tumors. Such predominance might be associated with a high rate of females in the non-CRLM group compared to the high rate of males in the CRLM group. Females are known to be more susceptible to genitourinary metastasis [23, 24]. Also, some patients in the non-CRLM group had very aggressive cancers, like melanoma, sarcoma, and genitourinary tract cancers. Such tumors are prominent in younger patients [17, 18, 25]; thus, it may lead to age differences between the study groups, where non-CRLM patients were younger. On the other hand, due to the retrospective design of the study, we cannot exclude the selection bias, that elderly patients with non-CRLM were not considered for resection. While the majority of non-CRLM are known for aggressive biological behavior, it was not surprising that DFS in the non-CRLM group was lower, although, despite faster relapses in the non-CRLM group, the comparable OS should encourage surgeons to consider resection for non-CRLM as well.

Limitations of the study

The present study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective design study and it might lead to selection bias to perform liver resection for non-CRLM only in very selected cases, although, to our best knowledge, there are no large, prospective, randomized trials evaluating the role of surgery for non-CRLM. Second, the non-CRLM group was heterogeneous by including patients with different types of cancers, although it is important to mention that surgery for non-CRLM remains non-standard; thus, accumulating a sufficient sample size for a homogenous group of one type of metastases is hardly realizable.

Third, the study may be underpowered due to a relatively small number of patients included.

Conclusions

In this study, we confirmed comparable short- and long-term outcomes after liver resection for CRLM and non-CRLM. Surgical resection should be encouraged as an option in well-selected patients with non-CRLM.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CRLM:

-

Colorectal liver metastasis

- DFS:

-

Disease-free survival

- OS:

-

Overall survival

References

Adam R, De Gramont A, Figueras J, Guthrie A, Kokudo N, Kunstlinger F, et al. The oncosurgery approach to managing liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Oncologist. 2012;17(10):1225–39.

Engstrand J, Nilsson H, Stromberg C, Jonas E, Freedman J. Colorectal cancer liver metastases - a population-based study on incidence, management and survival. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):78.

Adam R, de Gramont A, Figueras J, Kokudo N, Kunstlinger F, Loyer E, et al. Managing synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41(9):729–41.

Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B, Arnold D, Group EGW. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl 3):iii1–9.

Parisi A, Trastulli S, Ricci F, Regina R, Cirocchi R, Grassi V, et al. Analysis of long-term results after liver surgery for metastases from colorectal and non-colorectal tumors: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2016;30:25–30.

Vasavada D, Mehta S, Parhad S. 38 hepatic resection-scope for general surgeon! J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2011;1(2):149–50.

Imamura H, Seyama Y, Kokudo N, Maema A, Sugawara Y, Sano K, et al. One thousand fifty-six hepatectomies without mortality in 8 years. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1198–206 discussion 1206.

Triantafyllidis I, Gayet B, Tsiakyroudi S, et al. Perioperative and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic liver resections for non-colorectal liver metastases [published online ahead of print, 2019 Oct 4]. Surg Endosc, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-07148-4.

Aghayan DL, Kalinowski P, Kazaryan AM, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection for non-colorectal non-neuroendocrine metastases: perioperative and oncologic outcomes. World J Surg Oncol. 2019 Sep;17(1):156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1700-y.

Holzner PA, Makowiec F, Klock A, et al. Outcome after hepatic resection for isolated non-colorectal, non-neuroendocrine liver metastases in 100 patients - the role of the embryologic origin of the primary tumor. BMC Surg. 2018 Oct;18(1):89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-018-0424-1.

Sano K, Yamamoto M, Mimura T, et al. Outcomes of 1,639 hepatectomies for non-colorectal non-neuroendocrine liver metastases: a multicenter analysis. Journal of Hepato-biliary-pancreatic Sciences. 2018 Nov;25(11):465–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.587.

Primrose JN. Surgery for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(9):1313–8.

Liang Y, Lin C, Zhang B, Cao J, Chen M, Shen J, et al. Perioperative outcomes comparing laparoscopic with open repeat liver resection for post-hepatectomy recurrent liver cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2020;79:17.

Veereman G, Robays J, Verleye L, Leroy R, Rolfo C, Van Cutsem E, et al. Pooled analysis of the surgical treatment for colorectal cancer liver metastases. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;94(1):122–35.

Moris D, Ronnekleiv-Kelly S, Rahnemai-Azar AA, Felekouras E, Dillhoff M, Schmidt C, et al. Parenchymal-sparing versus anatomic liver resection for colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(6):1076–85.

Garritano S, Selvaggi F, Spampinato MG. Simultaneous minimally invasive treatment of colorectal neoplasm with synchronous liver metastasis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:9328250.

Yoo TG, Cranshaw I, Broom R, Pandanaboyana S, Bartlett A. Systematic review of early and long-term outcome of liver resection for metastatic breast cancer: is there a survival benefit? Breast. 2017;32:162–72.

Gandy RC, Bergamin PA, Haghighi KS. Hepatic resection of non-colorectal non-endocrine liver metastases. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87(10):810–4.

Clift AK, Frilling A. Liver transplantation and multivisceral transplantation in the management of patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumours. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(20):2152–62.

House MG, Ito H, Gonen M, Fong Y, Allen PJ, DeMatteo RP, et al. Survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: trends in outcomes for 1,600 patients during two decades at a single institution. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(5):744–52 752-745.

Moris D, Tsilimigras DI, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Beal EW, Felekouras E, Vernadakis S, et al. Liver transplantation in patients with liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors: a systematic review. Surgery. 2017;162(3):525–36.

Montagnani F, Crivelli F, Aprile G, Vivaldi C, Pecora I, De Vivo R, et al. Long-term survival after liver metastasectomy in gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;69:11–20.

Neri F, Ercolani G, Di Gioia P, Del Gaudio M, Pinna AD. Liver metastases from non-gastrointestinal non-neuroendocrine tumours: review of the literature. Updat Surg. 2015;67(3):223–33.

Slupski M, Jasinski M, Pierscinski S, Wicinski M. Long-term results of simultaneous and delayed liver resections of synchronous colorectal cancer liver metastases. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:1119.

Uggeri F, Ronchi PA, Goffredo P, Garancini M, Degrate L, Nespoli L, et al. Metastatic liver disease from non-colorectal, non-neuroendocrine, non-sarcoma cancers: a systematic review. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:191.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RR contributed to data collection and analysis and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. AB contributed to data analysis and writing the manuscript. VS and MP contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript. KS contributed to data analysis, manuscript writing, and review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Vilnius regional biomedical research ethics committee approval (No. 158200-18/7-1054-553) was obtained before this study was conducted. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Račkauskas, R., Baušys, A., Sokolovas, V. et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of surgery for colorectal and non-colorectal liver metastasis: a report from a single center in the Baltic country. World J Surg Onc 18, 164 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-01944-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-01944-2