Abstract

Aim

The purpose of this study was to compare clinicopathological features of patients with non-schistosomal and schistosomal colorectal cancer to explore the effect of schistosomiasis on colorectal cancer (CRC) patients’ clinical outcomes.

Methods

Three hundred fifty-one cases of CRC were retrospectively analyzed in this study. Survival curves were constructed by using the Kaplan-Meier (K-M) method. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models were performed to identify associations with outcome variables.

Results

Colorectal cancer patients with schistosomiasis (CRC-S) were significantly older (P < 0.001) than the patients without schistosomiasis (CRC-NS). However, there were no significant differences between CRC-S and CRC-NS patients in other clinicopathological features. Schistosomiasis was associated with adverse overall survival (OS) upon K-M analysis (P = 0.0277). By univariate and multivariate analysis, gender (P = 0.003), TNM stage (P < 0.001), schistosomiasis (P = 0.025), lymphovascular invasion (P = 0.030), and lymph nodes positive for CRC (P < 0.001) were all independent predictors in the whole cohort. When patients were stratified according to clinical stage and lymph node metastasis state, schistosomiasis was also an independent predictor in patients with stage III–IV tumors and in patients with lymph node metastasis, but not in patients with stage I–II tumors and in patients without lymph node metastasis.

Conclusion

Schistosomiasis was significantly correlated with OS, and it was an independent prognostic factor for OS in the whole cohort. When patients were stratified according to clinical stage and lymph node metastasis state, schistosomiasis was still an independently unfavorable prognosis factor for OS in patients with stage III–IV tumors or patients with lymph node metastasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Growing pieces of evidence have emerged in recent decades that inflammation is the root of many malignant tumors [1, 2]. As the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the world [3], CRC represents a growing number of cancers that correlated with inflammatio n[1, 4, 5]. Schistosoma japonicum (S. japonicum), which is common in Southeast Asia [6], is regarded as a risk factor of CRC development [7]. Schistosomal infestation has been implicated in the etiology of several human malignancies including bladder, liver, and CRC [8, 9]. The prevalent view is that the sequestered eggs in the mucosa and submucosa incite a severe inflammatory reaction with cellular infiltration and consequent granuloma formation. This in turn leads to mucosal ulceration, microabscess formation, polyposis, and neoplastic transformation [10]. But the causal relationship between S. japonicum and CRC still remained controversial [11]. Some case reports and descriptive studies from Africa and the Middle East raised the possibility of an association between S. japonicum infestation and induction of CRC [12,13,14]. Nonetheless, the pathological evidence supporting this conclusion is rather weak, while some research demonstrated that S. japonicum infestation was unrelated with CRC [15].

In the 1950s, schistosomiasis was epidemic at a large scale in regions along the Yangtze River and in more than 400 counties in South China [16]. Because of the effective prevention and cure measures taken in China in recent years, schistosomiasis has been eliminated in most epidemic regions. However, its spread is not yet completely controlled and schistosomiasis occurs every year in a small number of people in the epidemic regions of China [17]. The Qingpu District of Shanghai used to be one of the 10 areas with serious schistosomiasis epidemic in China [18], and problems of treatment and outcome of a large number of late schistosomiasis patients left over from history are still remaining. Therefore, detailed knowledge about schistosomiasis is necessary to improve the accuracy of clinical prognosis prediction and will shed light on improving our ability to the prevention and control of schistosomiasis.

In the present study, we made a retrospective analysis of schistosomiasis and clinicopathological characteristics in 137 CRC-S patients and 214 CRC-NS patients to investigate the effect of schistosomiasis on CRC patients’ clinical outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

A total of 351 CRC patients were enrolled in this retrospective study. All patients had undergone primary surgical resection at Qingpu Branch of Zhongshan Hospital affiliated to Fudan University, from January 2008 to August 2016. All of the operations followed the principle: adequate resection margins, en bloc high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), and lymphadenectomy. All circumferential margins were cleared. The number of positive lymph nodes and total number of retrieved lymph nodes were recorded. The inpatient medical records and pathological reports were reviewed, and the patients were followed up by telephone. OS is defined as the interval from the surgical operation date to the last follow-up or death caused by CRC. Inclusion criteria included the following: (i) patients with CRC as primary focus, (ii) none of these patients had received any prior anti-tumor therapy, and (iii) patients were diagnosed as adenocarcinoma by pathology after resection of CRC. Exclusion criteria included the following: (i) Tis tumors, (ii) patients who lacked complete information, (iii) patients with synchronous malignancy, and (iv) patients with survival time less than 1 month.

Two expert pathologists reviewed HE-stained slides to determine the diagnosis and to restage the tumors according to the eighth edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).

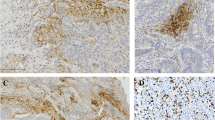

Detection of schistosome ova and assessment of tumor budding

Schistosome ova were observed in all of original HE-stained formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections (usually 4–6 slides), which were examined at × 10 and × 40 magnification fields using a conventional light microscope by two pathologists who were blinded to the clinical data. The diagnosis of schistosomiasis was done by finding schistosome eggs in HE-stained slides.

Tumor budding was defined as the presence of de-differentiated single cells or small clusters of up to 5 cells at the invasive front of CRC [19]. To assess tumor budding in the 10-HPF method [20], the invasive front is first scanned at low magnification (× 4 to × 10) to identify areas of highest budding density. Tumor buds are then counted under high magnification (× 40), and the tumor budding count is reported. The evaluation of tumor budding was conducted by two pathologists who were blinded to the clinical data. Five tumor budding counts were used as breakthrough point. In brief, tumor bud counts greater than or equal to 5 were defined as the high group, otherwise as the low group.

Statistical analysis

The association between schistosomiasis and clinicopathological characteristics was evaluated by using the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. The Kaplan-Meier (K-M) curves with log-rank tests were used to determine the prognostic significance for OS. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were used to identify independent prognostic factors, and P < 0.05 was defined as the criterion for variable deletion when performing backward stepwise selection. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Clinical characteristics in full cohort

A total of 351 surgically resected FFPE primary CRC samples were included in the study. In the whole cohort, 39.0% (137 out of 351) were infected with schistosoma (Fig. 1a). The clinical and pathological features of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. In the whole cohort, the age of patients at diagnosis ranged from 33 to 91 years (median, 69 years) and they were predominantly male (60.2%, 212 out of 351). By anatomic site, 27% tumors were in the rectum, 33% in the left colon, and 40% in the right colon. Lymph node metastasis was observed in 40% of patients, and 46% of patients were at late-stage disease, while patients without lymph node metastasis were 60%. On the basis of the AJCC Staging Manual (seventh edition), there were very few highly differentiated cases in the follow-up data. Thus, highly differentiated and moderately differentiated cases were classified as “well differentiation,” and poorly differentiated cases classified as “poor differentiation.” Seventy-six percent cases were well differentiated, and 24% were poorly differentiated. As shown in Table 1, lymphovascular invasion, perineura invasion, lymph nodes positive for CRC, and tumor budding were prone to appear in patients with stage III–IV tumors or patients with lymph node metastasis. More poorly differentiated tumors and deeper tumor invasion depth were also mostly observed in patients with late tumor stage or patients with lymph node metastasis. The distribution trend of other clinicopathological features, such as colonic perforation, ulceration, and histological type, was similar within different subgroups.

Survival analysis

The median follow-up time was 62.4 (1.25–134.4) months. During the follow-up, there were 41.6% (146 out of 351) patients who died. Mean and median time to OS was 62.54 and 62.85, respectively.

To investigate the association between schistosomiasis and clinical outcomes, we conducted K-M analysis according to schistosoma infection status. Result demonstrated that schistosoma infection was significantly associated with poor survival in total CRC patients (median survival time, 80.82 for CRC-S set and 119.20 for CRC-NS set; P = 0.0277) (Fig. 1b).

Further analysis was conducted to explore the effect of schistosoma infection on CRC patients with similar stage tumors. In stage I–II set (N = 192), a K-M curve was plotted and found that schistosoma infection (40%) was uncorrelated with survival (P = 0.5018) (Fig. 2a). Nevertheless, in stage III–IV set (N = 159), K-M analysis showed a significant correlation between schistosoma infection and OS (P = 0.0260) (Fig. 2b).

K-M analysis of OS in stratified CRC. a Patients with stage I–II tumors (N = 192, P = 0.5018). b Patients with stage III–IV tumors (N = 159, P = 0.0260). c Patients with lymph node metastasis (N = 144, P = 0.0249). d Patients without lymph node metastasis (N = 207, P = 0.4005). P value was calculated by log-rank test

In patients with lymph node metastasis (N = 144), schistosoma infection was observed in 39% (56 out of 144) CRC patients and associated with poor survival (P = 0.0249) (Fig. 2c). In contrast, there was no statistically significant difference observed in OS between CRC-S and CRC-NS patients without lymph node metastasis (P = 0.4005) (Fig. 2d).

Univariate and multivariate analysis

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine factors that may influence OS of CRC patients. In the whole cohort, by univariate analysis and multivariate analysis (Table 2), gender (P = 0.003), TNM stage (P < 0.001), schistosomiasis (P = 0.025), lymphovascular invasion (P = 0.030), and lymph nodes positive for CRC (P < 0.001) were significantly independent predictors. Schistosomiasis was statistically significantly associated with decreasing OS.

In late-stage (III–IV) CRC patients (Table 2), gender (P = 0.030), pathological T stage (P = 0.12), tumor differentiation (P = 0.016), schistosoma infection (P = 0.008), and lymph nodes positive for CRC (P = 0.004) were significantly independent prognostic factors for OS, while in early stage (I–II), lymph nodes positive for CRC (P = 0.007) was the only independent prognostic factor for OS in multivariate analysis.

In patients with lymph node metastasis (Table 2), gender (P = 0.026), pathological T stage (P = 0.025), schistosoma infection (P = 0.023), and lymph nodes positive for CRC (P = 0.003) were independent prognostic factors. In patients without lymph node metastasis (Table 2), TNM stage (P < 0.001) and tumor budding (P = 0.014) but not schistosoma infection were associated with OS in multivariate analysis. These results further proved that schistosoma infection may have different effects on CRC patients’ clinical outcomes, especially for patients with stage III–IV tumor and patients with lymph node metastasis.

Association of schistosomiasis with clinicopathological features

The relationship between schistosomiasis and clinicopathological features is shown in Table 3. Patients with schistosomiasis were significantly older than the patients without schistosomiasis (median age 74.0 years vs 64.0 years, P < 0.001). The clinical stage of patients with and without schistosomiasis was similar (P = 0.816). In the total cohort, the male/female ratio was also higher in the CRC-S set (1.67 vs 1.43). Besides, in patients with lymph node metastasis, there were significant associations between male sex and female sex (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in other clinicopathological characteristics between CRC-NS and CRC-S sets.

In order to further investigate the effect of schistosomiasis on particular CRC population, we divided the whole cohort into different groups according to their clinical stage or the state of lymph node metastasis and further subgrouped them into CRC-S and CRC-NS set based on schistosomiasis. Except age, there were no correlations between other clinicopathological features and schistosomiasis when compared between CRC-NS and CRC-S sets in different groups (Table 3).

Discussion

At present, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that S. haematobium has a role in causing some types of bladder cancer [21,22,23] and hepatocellular carcinoma [6, 10]. There is limited evidence to suggest that S. japonicum leads to CRC.

Our study demonstrated that schistosomiasis was an independently unfavorable factor for OS (P = 0.0260, Fig. 1b; P = 0.025, Table 2). These results indicated that schistosomiasis plays an important role in CRC progression and metastases. Shindo [24] reviewed 276 cases of large intestinal cancer with schistosomiasis and found significant differences between carcinoma with schistosomiasis and non-schistosomiasis-associated carcinoma in symptoms, age, sex, and histological findings, suggesting that schistosomiasis could induce the carcinoma. Ye et al. [25] reported that intestinal schistosomiasis was a risk factor for CRC and that the lesions caused by the disease might be considered precancerous. Liu et al. [26] reported that the history of colon schistosomiasis was a probable risk factor for the development of colorectal neoplasia, but only a few studies reported the clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of patients with schistosomal CRC. This might be explained as follows. Firstly, there is little relevant clinical data in the medical literature, limited to case reports; physicians know little about it [27, 28]. Secondly, cases of colonic schistosomiasis are rare leading to a small sample size and potential bias in data analysis. Previous reports [29, 30] showed that the development of CRC-S occurs in a younger age group unlike our findings. This might be explained by the following reasons. First, since effective prevention and control measures were taken in China in 1983, the infection rate has decreased, which result in large quantity and relatively younger CRC-NS patients. Second, this disparity may be related to differences in hereditary factors and environmental carcinogens. Our results showed that there is also a male predominance (61%, Table 1) in the cohort, although there was no significant difference between CRC-NS and CRC-S patients (Table 3). The Qingpu District of Shanghai was previously predominantly rural and, as more males were engaged in farm work, is likely to be at greater risk for exposure [31,32,33].

In the cohort, there were 22 (1.7%) patients who have stage IV tumors, and the survival time ranged from 1.25 to 118 months. Although it is well known that stage IV tumors have a poor prognosis, we want to investigate the impact of schistosoma on CRC in the complete process.

Schistosomiasis was statistically significant for OS in the univariate analysis and was an independent prognosis factor in multivariate analysis in the whole cohort (P = 0.025, HR = 1.458, 95% CI = 1.049–2.027). When patients were stratified based on clinical stage or state of lymph node metastasis, schistosomiasis was also a significantly independent predictor, except in patients with stage I–II tumor or without lymph node metastasis. Therefore, our observation indicates that schistosomiasis may be a considerable risk for patients in different clinical stages, especially in the late clinical stage. This conclusion may increase the debate that schistosomiasis is a weak risk of CRC [5, 34, 35].

Our study has several limitations. First, because it was performed at a single institution, the uniformity of the results may be low. Further work will be needed to validate the present results. Second, patient selection bias is a possibility due to the nature of the retrospective study. Third, although we found a negative correlation between schistosomiasis and CRC outcomes, the precise functional roles of schistosomiasis in CRC progression and its underlying molecular mechanisms remain obscure. Chen et al. observed a variable degree of colonic epithelial dysplasia in 60% of cases with S. japonicum colitis and regarded these changes as a transition on the way towards cancer development in schistosomal colonic disease [36]. A similar conclusion was drawn by Yu et al. from their studies on different types of schistosomal egg polyps [34]. All these results suggested the pro-tumor mechanisms of S. japonicum in tumor tissues. Therefore, further analysis about the functional roles of schistosoma infection and underlying molecular mechanisms needs to be investigated. In addition, we were not sure if any of these patients suffered from familial cancer syndromes, such as Lynch syndrome. It was known that the proportion of patients with familial polyps and hereditary non-polyposis CRC syndrome is higher in young patients (≤ 40 years old) [37, 38]. In our cohort, there were seven patients (0.02%) under 40 years old. However, work will continue to examine this possibility. Lastly, it was reported that schistosomiasis results from the host’s immune response to schistosome eggs and the granulomatous reaction evoked by the antigens they secrete [39], and the process of granuloma formation will be accompanied by chronic inflammatio n[40, 41], which may induce the development of tumor. However, we could not provide evidence in this study and detection of inflammatory markers will be conducted to strengthen the hypothesis in further work.

In summary, our observations support the pathogenetic role of schistosomiasis and shed light on the adverse effects of schistosomiasis on CRC patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CRC-NS:

-

Patients without schistosomiasis

- CRC-S:

-

Colorectal cancer patients with schistosomiasis

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- IMA:

-

Inferior mesenteric artery

- K-M:

-

Kaplan-Meier

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- S. japonicum :

-

Schistosoma japonicum

References

Mantovani A. Cancer: inflaming metastasis. Nature. 2009;457(7225):36–7.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–74.

Bray F, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

OE, H.S., et al., Colorectal carcinoma associated with schistosomiasis: a possible causal relationship. World J Surg Oncol, 2010. 8: p. 68.

Chen MG. Assessment of morbidity due to Schistosoma japonicum infection in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2014;3(1):6.

Gryseels B, et al. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368(9541):1106–18.

Hamid HKS. Schistosoma japonicum-associated colorectal cancer: a review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;100(3):501–5.

Yosry A. Schistosomiasis and neoplasia. Contrib Microbiol. 2006;13:81–100.

Eder BVA, et al. Sigmoid colon cancer due to schistosomiasis. Infection. 2019;47(6):1071–2.

Ross AG, et al. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(16):1212–20.

Schwartz E, Rozenman J. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(10):766–8 author reply 766-8.

Uthman S, et al. Association of Schistosoma mansoni with colonic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86(9):1283–4.

Al-Mashat F, et al. Rectal cancer associated with schistosomiasis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Saudi Med. 2001;21(1-2):65–7.

Ameh EA, Nmadu PT. Colorectal adenocarcinoma in children and adolescents: a report of 8 patients from Zaria. Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2000;19(4):273–6.

Cheever AW, et al. Schistosoma mansoni and S. haematobium infections in Egypt. III. Extrahepatic pathology. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27(1 Pt 1):55–75.

McManus DP, et al. Conquering ‘snail fever’: schistosomiasis and its control in China. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7(4):473–85.

Zhu, R. and J.J.C.J.o.S.C. Xu, [Epidemic situation of oversea imported schistosomiasis in China and thinking about its prevention and control]. 2014. 26(2): p. 111-114.

Yu SZ. Schistosomiasis must be eradicated: a review of fighting schitosomiasis in Qingpu, Shanghai. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2016;37(7):1044–6.

Koelzer VH, Zlobec I, Lugli A. Tumor budding in colorectal cancer--ready for diagnostic practice? Hum Pathol. 2016;47(1):4–19.

Horcic M, et al. Tumor budding score based on 10 high-power fields is a promising basis for a standardized prognostic scoring system in stage II colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2013;44(5):697–705.

Elsebai I. Parasites in the etiology of cancer--bilharziasis and bladder cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 1977;27(2):100–6.

Bedwani R, et al. Schistosomiasis and the risk of bladder cancer in Alexandria. Egypt. Br J Cancer. 1998;77(7):1186–9.

Barnett R. Schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2018;392(10163):2431.

Shindo K. Significance of Schistosomiasis japonica in the development of cancer of the large intestine: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1976;19(5):460–9.

Ye C, et al. Endoscopic characteristics and causes of misdiagnosis of intestinal schistosomiasis. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8(4):1089–93.

Liu W, et al. Schistosomiasis combined with colorectal carcinoma diagnosed based on endoscopic findings and clinicopathological characteristics: a report on 32 cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(8):4839–42.

Issa I, Osman M, Aftimos G. Schistosomiasis manifesting as a colon polyp: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:331.

Li WC, Pan ZG, Sun YH. Sigmoid colonic carcinoma associated with deposited ova of Schistosoma japonicum: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(37):6077–9.

Xu Z, Su DL. Schistosoma japonicum and colorectal cancer: an epidemiological study in the People’s Republic of China. Int J Cancer. 1984;34(3):315–8.

El-Bolkainy MN, et al. The impact of schistosomiasis on the pathology of bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48(12):2643–8.

Madbouly KM, et al. Colorectal cancer in a population with endemic Schistosoma mansoni: is this an at-risk population? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22(2):175–81.

Xiao, G., et al., Analysis of risk factors and changing trends the infection rate of intestinal schistosomiasis caused by S. japonicum from 2005 to 2014 in Lushan city. Parasitol Int, 2018. 67(6): p. 751-758.

Wang Z, et al. Comparison of the clinicopathological features and prognoses of patients with schistosomal and nonschistosomal colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2020;19(3):2375–83.

Yu, X.R., et al., Histological classification of schistosomal egg induced polyps of colon and their clinical significance. An analysis of 272 cases. Chin Med J (Engl), 1991. 104(1): p. 64-70.

Ojo OS, Odesanmi WO, Akinola OO. The surgical pathology of colorectal carcinomas in Nigerians. Trop Gastroenterol. 1992;13(2):64–9.

Chen MC, et al. Colorectal cancer and schistosomiasis. Lancet. 1981;1(8227):971–3.

Yantiss RK, et al. Clinical, pathologic, and molecular features of early-onset colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(4):572–82.

Antelo M, et al. A high degree of LINE-1 hypomethylation is a unique feature of early-onset colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45357.

Boros DL, Warren KS. Delayed hypersensitivity-type granuloma formation and dermal reaction induced and elicited by a soluble factor isolated from Schistosoma mansoni eggs. J Exp Med. 1970;132(3):488–507.

Peterson WP, Von Lichtenberg F. Studies on granuloma formation. IV. In vivo antigenicity of schistosome egg antigen in lung tissue. J Immunol. 1965;95(5):959–65.

Colley DG, Secor WE. Immunology of human schistosomiasis. Parasite Immunol. 2014;36(8):347–57.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

This work is supported by the China Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (grant no. 20194Y0162).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weixia Wang contributed to the data analysis, manuscript editing, article revision, and data supplement. Kui Lu and Limei Wang assessed all the dyeing slices. Hongyan Jing contributed to the research design, data analysis, and manuscript writing. Weiyu Pan, Sinian Huang, Yanchao Xu, Dacheng Bu, Meihong Cheng, Jing Liu, Jican Liu, Weidong Shen, Yingyi Zhang, and Junxia Yao contributed to the data collection and performed the experiments. Ting Zhu contributed to the data analysis and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Fudan University (ethical approval number 2019-017), in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Prior written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W., Lu, K., Wang, L. et al. Comparison of non-schistosomal colorectal cancer and schistosomal colorectal cancer. World J Surg Onc 18, 149 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-01925-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-01925-5