Abstract

Background

Rectum cancer is a type of colorectal cancer. Its etiology and etiopathogenesis are similar to other colon diseases. We aimed to evaluate the tumor budding for predicting prognosis of resected rectum cancer patients.

Methods

We retrospectively collected the data of 75 operated rectum adenocarcinoma patients who were treated neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy between 2013 and 2018 in Umraniye Research and Training Hospital and Acıbadem University Medical Oncology Outpatient Clinic. Tumor budding was investigated as a prognostic factor for disease-free survival.

Results

This study included 75 rectum cancer patients and 51 were male (68%). Median age was 56 (range 19 to 77 years). There were 29 (39%) and 46 (61%) patients in tumor budding low-intermediate and high groups respectively. In multivariate analysis, tumor budding was found to be an independent prognostic factor for disease-free survival (p = 0.00).

Conclusions

According to our study, having high tumor budding suggests a high likelihood of relapse. Therefore, we might need additional follow-up protocol in these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide. It is the third most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and second in women. Several trials have shown the relationship between tumor budding and disease prognosis in colorectal cancer. The aim of our study was to investigate the prognostic value of tumor budding in patients with rectum cancer who underwent radical curative surgery after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide. It is the third most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and second in women [1]. Although CRC mortality has been rapidly declining since 1990, nowadays, its rate is approximately 1.7 to 1.9% per year [2]. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is the standard therapeutic approach in rectal cancer [3, 4]. There is no ideal marker for predicting prognosis after chemoradiotherapy. Factors affecting prognosis in colorectal cancers can be summarized as individual (age, sex, family history), clinical, biochemical, pathologic prognostic factors, tumor progression at the time of diagnosis, and adjunctive therapy (surgery, adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant treatment) [5, 6]. We know that about 25% of patients with early-stage colorectal cancer develop distant metastases [7]. The TNM staging system may not be a good candidate for a prognostic parameter in colorectal cancer because some patients in the same pathological stage may present various oncological outcomes such as early recurrence or mortality [8]. Several other novel histopathological parameters are also being explored as potential prognostic biomarkers for colorectal cancer, such as tumor budding (TB), poorly differentiated clusters (PDCs), extramural vascular (vein) invasion (EMVI), perineural invasion (PNI), tumor deposits (TDs), mucin pools (MPs), and extranodal extension of nodal metastasis (ENE), but some of these are yet to be fully investigated in larger phase trials for their association with prognosis of colorectal cancer. For example, ENE has been reported to be associated with a significantly increased risk of recurrence and mortality in a meta-analysis [9, 10].

Tumor budding was defined as the presence of isolated single cells or small cell clusters of less than five cells in the literature. Tumor buddings are disturbed within the stroma at the tumor margin. They tend to lose adhesion and dissociate, and this situation causes the tumor to be aggressive. There is a close relationship between tumor budding and the process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. In this transitional process, epithelial cells lose intracellular and cell-matrix contacts mediated by E-cadherin, resulting in invasion and ultimately metastatic cancer spread [11,12,13]. Several trials have shown the relationship between tumor budding and disease prognosis in colorectal cancer. Especially, tumor budding might be closely related to poor survival and high risk of recurrence [14, 15].

The aim of our study was to investigate the prognostic value of tumor budding in patients with rectum cancer who underwent radical curative surgery after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

Method

Patients

We retrospectively collected the data of 80 operated rectum adenocarcinoma patients who were treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy between 2013 and 2018 in Umraniye Research and Training Hospital and Acıbadem University Medical Oncology Outpatient Clinic. Inclusion criteria were histological diagnosis of non-metastatic rectal adenocarcinoma, treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, and having complete medical records. All patients were older than 18 years old. Five patients with a complete response were excluded from the study. A total of 75 patients were evaluated.

All patients received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Radiotherapy was given for a total of 45 Gy/28 days. Capecitabine 825 mg/m2/day or 5-fluorouracil 200 mg/m2 D1-5 weekly was administered. All of the patients were operated on an average of 8–12 weeks.

We defined the follow-up duration as the time from the start of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy treatment until death of any reason/the last visit. Disease-free survival was defined as the time from date of surgery until radiological progression or death/the last visit. The data cutoff date was accepted on September 2018.

Pathological evaluation

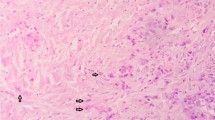

Seventy-five patients’ pathology slides from the adenocarcinoma area are kept in department storage and were evaluated for tumor budding in a light microscope. All rectum specimens were sliced transversely at 3–4-mm intervals, and at least eight tumor samples were taken in every specimen. However, patients’ paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were not cut into any section for hematoxylin and eosin and/or other histochemical or immunohistochemical staining.

A three-tier system, which is recommended by the ITBCC (The International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference) 2016 group, was used [16]. The ITBCC group also recommends that, in addition to the Bd category, the absolute bud count should be provided (e.g., Bd 3 (count 17)). We grouped the patients to be low-intermediate and high due to the small number of patients.

The three-tier system is categorized as:

-

0–4 buds—low budding (Bd 1)

-

5–9 buds—intermediate budding (Bd 2)

-

10 or more buds—high budding (Bd 3)

Tumor budding was assessed in one hotspot (in a field measuring 0.785 mm2) at the invasive front. Firstly, we selected the H&E slide with the greatest degree of budding at the invasive front and then scanned ten individual fields at medium power (10× objective) to identify the hotspot area. Ultimately, we counted tumor buds in the selected hotspot area (20× objective) and divided the bud count by the normalization factor to determine the tumor bud count per 0.7 85mm2 as defined by the ITBCC group.

The tumor grading was categorized into well differentiated (> 95% gland formation), moderately differentiated (50–95% gland formation), and poorly differentiated (< 50% gland formation). Patients were grouped into four categories according to the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging, based on the American Joint Cancer Committee (AJCC) cancer staging manual 7th edition.

Tumor regression was assessed by the four-tier AJCC/CAP tumor regression grading system. It is categorized as [17]:

-

No viable cancer cells—0 (complete response)

-

Single cells or small groups of cancer cells—1 (moderate response)

-

Residual cancer outgrown by fibrosis—2 (minimal response)

-

Minimal or no tumor kill, extensive residual cancer—3 (poor response)

Statistical analysis

Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method from the operated date. Prognostic factors were compared using the log-rank test in univariate analysis. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were also calculated. All p values were two-sided in the tests, and p values of 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multivariate analysis was carried out using the Cox proportional hazards model to assess the effect of prognostic factors on survival.

Results

Patients demographic and clinical characteristics outcomes

Data from a total of 75 operated rectum cancer patients treated with systemic treatment and available medical records were analyzed retrospectively. Fifty-one of the seventy-five patients were male (68%) and the median age was 56 (range 19–77 years). Pretreatment demographic and clinical characteristics of patients based on tumor budding groups for the entire study cohort were outlined in Table 1. There were 29 (39%) and 46 (61%) patients in tumor budding low-intermediate and high groups respectively. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were similar between the two groups, with the exception of microsatellite instability. Tumor budding high group had more microsatellite instability patients compared to the low-intermediate group (p = 0.02).

Survival outcomes

Adjuvant treatment, relapse, mutational status characteristics, and overall clinical outcomes are shown in Table 2. Median follow-up duration was 35 months (range 9–65 months). During the follow-up period, 41(55%) of the 75 patients relapsed. For the whole cohort, median disease-free survival (DFS) was 30 months (95% CI 26.8–33.1) (Fig. 1a). According to the tumor budding low-intermediate and high groups, median DFS was 43 months in the tumor budding low-intermediate group (95% CI 25.7–60.2) and 28 months in the high group (95% CI 25.2–30.7) (p = 0.003) (Fig. 1b).

Univariate and multivariate outcomes

Univariate and multivariate analysis results are summarized in Table 3. Grade (poorly vs well-intermediate), stage groups (0–2 vs 3), lymph nodes (N0 vs N1–2), microsatellite instability (low vs high), and tumor budding (low-intermediate vs high) had a significant statistical association with DFS in univariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, grade and tumor budding status were found to be independent prognostic factors for DFS (p = 0.00).

Discussion

Our study is a report on high tumor budding status relationship of survival. We demonstrated that high tumor budding was correlated with poor disease-free survival and found independent prognostic factor by multivariate analysis.

In the recent years, several trials showed that tumor budding associated with different clinical and histological parameters such as tumor site, tumor size, histologic type, grade, nodal involvement, AJCC stage, distant metastasis, and local recurrence. Ohtsuki et al. evaluated 149 patients with colorectal cancer and reported that tumor budding significantly associated with wall penetration, the incidence of lymph node metastasis, and cancer recurrence [18]. Another study reported that high budding associated with an infiltrative growth pattern and lymphovascular invasion. Five-year cancer-specific survival was significantly poorer in high compared with low budding groups [19]. Sevda et al. showed a statistically significant relationship between high-grade tumor budding density and histological grade, lymph node involvement, and vascular invasion in their research [20]. Conservely, in our study, we did not find an association between tumor budding, histological grade, and lymph node involvement. We evaluated only patients with treated neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy which situation may have affected our assessment of tumor grade and lymph node involvement.

There are several studies in the literature investigating the relationship between tumor budding and disease-free survival. In a study of 138 patients diagnosed with stage 2 colon cancer, Tanaka et al. reported that the cumulative disease-specific survival rates at 5 years for patients with tumor budding low and high were 98 and 74%, respectively [21]. As mentioned above, Wang et al. also showed that the 5-year cancer-specific survival was significantly poorer in high compared with low budding groups [19]. Petrelli et al., in their meta-analysis, showed that tumor budding was a significant histologic marker in the prognosis of stage 2 colorectal cancer and high-grade tumor budding in these patients is related to a 25% increase at the risk of death in 5 years. Researchers suggested that this may be a useful prognostic factor when deciding the adjuvant treatment in these patients groups [22]. Another systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2016 have confirmed the impact of tumor budding in colorectal cancer, and it can be a predictive marker of recurrence and cancer-related death at 5 years [23]. Also, Cappellesso et al., in their meta-analysis which included 41 studies involving a total of 10,137 patients, demonstrated the prognostic value of tumor budding in pT1 colorectal cancer patients. Nodal metastasis was 28.5% in tumor budding positive and 7.2% in negative patients. Researchers revealed that tumor budding positivity increased the risk of nodal metastasis by 6.44 (OR value of 6.44 (95% CI 5.26–7.87; p < 0.0001; I2 = 30%; 41 studies) and concluded it was an independent histologic prognostic biomarker in pT1 colorectal cancer [24].

Jager et al. investigated the prognostic value of tumor budding for neoadjuvant treatment response in a cohort of 128 rectum cancer patients. Positive tumor budding was associated with significantly reduced T-level downstaging, tumor regression, and poor 5-year relapse-free survival. Besides, a multivariate analysis confirmed a positive tumor budding after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy as a negative predictive histologic biomarker for relapse-free survival [25]. In another study conducted in 2012 in which the same group of patients was included, tumor budding was found to be an independent prognostic factor in terms of disease-free survival [26]. Tumor regression especially pathological complete response following neoadjuvant treatment is related to long-term survival with low rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis [27]. Therefore, a standardized pathological evaluation after chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer is recommended. Tumor regression grade (TRG) has been defined as a useful method of scoring tumor response [28, 29]. Fokas et al. reported that higher TRG after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy predicted a favorable long-term outcome [30]. In our study, the relationship between tumor budding and disease-free survival is similar to the literature. We found a median DFS of 43 months in tumor budding low-intermediate groups and 28 months in high groups. One and three-year disease-free survival rates were higher in the tumor budding low-intermediate group compared to the high group. High tumor budding in multivariate analysis was found as an independent prognostic factor for disease-free survival. On the other hand, we did not find any significant association with tumor response, lymph node involvement, and grade between two groups. Unlike Jager et al., this situation may be related to the different groupings according to tumor budding in our study. In conclusion, further phase 3 trials are needed to validate TRG and tumor budding (or related with together use) as a surrogate marker for survival in rectum cancer patients after neoadjuvant treatment. The current literature which is investigating the prognostic role of tumor budding in patients with rectum cancer who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy was outlined in Table 4.

Tumor budding has also evaluated in other gastrointestinal cancers such as squamous esophageal cancer, gastric adenocarcinoma, and pancreatic cancer patients [31,32,33]. High tumor budding in the three cancers has also shown to be associated with poor prognosis. Additionally, several non-gastrointestinal cancers such as lung cancer, head and neck carcinomas, and breast cancer have shown that tumor budding was a prognostic factor [34,35,36].

Conclusion

We had some limitations in our study. Firstly, the relatively low number of patients may cause selection bias. Secondly, we also had to divide the patients into two groups. Therefore, we could not evaluate the relationship between the low and intermediate budding group clearly. Patients with high tumor budding have shorter disease-free survival than patients with low-intermediate tumor budding. In our patient population, having high tumor budding suggests a high likelihood of relapse. Therefore, we might need additional follow-up protocol in these patients.

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108.

Cronin KA, Lake AJ, Scott S, Sherman RL, Noone AM, Howlader N, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part I: national cancer statistics. Cancer. 2018;124:2785.

Roh MS, Colangelo LH, O'Connell MJ, Yothers G, Deutsch M, Allegra CJ, et al. Preoperative multimodality therapy improves disease-free survival in patients with carcinoma of the rectum: NSABP R-03. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5124.

Gérard JP, Conroy T, Bonnetain F, Bouché O, Chapet O, Closon-Dejardin MT, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy with or without concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin in T3-4 rectal cancers: results of FFCD 9203. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4620.

Sandler RS. Epidemiology and risk factors for colorectal cancer. Gastroenteol Clin North Am. 1996;25:717–33.

Burt RW. Familial risk and colorectal cancer. Gastroenteol Clin North Am. 1996;25:793–805.

Glimelius B, Cavalli-Björkman N. Metastatic colorectal cancer: current treatment and future options for improved survival. Medical approach—present status. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:296–314.

Puppa G, Sonzogni A, Colombari R, Pelosi G. TNM staging system of colorectal carcinoma: a critical appraisal of challenging issues. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:837–52.

Athanasakis E, Xenaki S, Venianaki M, Chalkiadakis G, Chrysos E. Newly recognized extratumoral features of colorectal cancer challenge the current tumor-node-metastasis staging system. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31(5):525–34.

Veronese N, Nottegar A, Pea A, et al. Prognostic impact and implications of extracapsular lymph node involvement in colorectal cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:42–8.

Hase K, Shatney C, Johnson D, Trollope M, Vierra M. Prognostic value of tumor “budding” in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(7):627–35.

Ueno H, Murphy J, Jass JR, Mochizuki H, Talbot IC. Tumour ‘budding’ as an index to estimate the potential of aggressiveness in rectal cancer. Histopathology. 2002;40(2):127–32.

Lugli A, Karamitopoulou E, Zlobec I. Tumour budding: a promising parameter in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(11):1713–7.

Park KJ, Choi HJ, Roh MS, Kwon HC, Kim C. Intensity of tumor budding and its prognostic implications in invasive colon carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(8):1597–602.

Choi HJ, Park KJ, Shin JS, Roh MS, Kwon HC, Lee HS. Tumor budding as a prognostic marker in stage-III rectal carcinoma. Int J Color Dis. 2007;22(8):863–8.

Lugli A, Kirsch R, Ajioka Y, et al. Recommendations for reporting tumor budding in colorectal cancer based on the International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC) 2016. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(9):1299.

Jäger T, Neureiter D, Urbas R, et al. Applicability of American Joint Committee on Cancer and College of American Pathologists Regression Grading System in Rectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(8):815–26.

Ohtsuki K, Koyama F, Tamura T, et al. Prognostic value of immunohistochemical analysis of tumor budding in colorectal carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:1831–6.

Wang LM, Kevans D, Mulcahy H, et al. Tumor budding is a strong and reproducible prognostic marker in T3N0 colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:134–41.

Sevda SB, Gülsün IM, Ibrahim MC, et al. Tumor budding in colorectal carcinomas. Turk J Pathol. 2012;28:61–6.

Tanaka M, Hashiguchi Y, Ueno H, Hase K, Mochizuki H. Tumor budding at the invasive margin can predict patients at high risk of recurrence after curative surgery for stage II, T3 colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1054–9.

Petrelli F, Pezzica E, Cabiddu M, et al. Tumour budding and survival in stage II colorectal cancer: a systematic review and pooled analysis. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46(3):212–8.

Rogers AC, Winter DC, Heeney A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of tumor budding in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:831–40.

Cappellesso R, Luchini C, Veronese N, et al. Tumor budding as a risk factor for nodal metastasis in pT1 colorectal cancers: a meta-analysis. Hum Pathol. 2017;65:62–70 Epub 2017 Apr 22.

Jäger T, Neureiter D, Fallaha M, et al. The potential predictive value of tumor budding for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy response in locally advanced rectal cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2018;194(11):991–1006.

Du C, Xue W, Li J, Cai Y, Gu J. Morphology and prognostic value of tumor budding in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant radiotherapy. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1061–7.

ST M, Heneghan HM, Winter DC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes following pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99(7):918–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.8702. Epub 2012 Feb 23.

Dworak O, Keilholz L, Hoffmann A. Pathological features of rectal cancer after preoperative radiochemotherapy. Int J Color Dis. 1997;121:19–23.

Ryan R, Gibbons D, Hyland JMP. Pathological response following long-course neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Histopathology. 2005;47:141–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02176.

Fokas E, Ströbel P, Fietkau R, et al. Tumor regression grading after preoperative chemoradiotherapy as a prognostic factor and individual-level surrogate for disease-free survival in rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(12):djx095.

Che K, Zhao Y, Qu X, Pang Z, Ni Y, Zhang T, Du J, Shen H. Prognostic significance of tumor budding and single cell invasion in gastric adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:1039–47 [PMID: 28255247. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S127762.

Miyata H, Yoshioka A, Yamasaki M, Nushijima Y, Takiguchi S, Fujiwara Y, Nishida T, Mano M, Mori M, Doki Y. Tumor budding in tumor invasive front predicts prognosis and survival of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinomas receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 2009;115:3324–34 [PMID: 19452547 DOI: 10.1002/cncr.24390].

Masugi Y, Yamazaki K, Hibi T, Aiura K, Kitagawa Y, Sakamoto M. Solitary cell infiltration is a novel indicator of poor prognosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1061–8 [PMID: 20413143]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2010.01.016.

Kadota K, Yeh YC, Villena-Vargas J, Cherkassky L, Drill EN, Sima CS, Jones DR, Travis WD, Adusumilli PS. Tumor budding correlates with the protumor immune microenvironment and is an independent prognostic factor for recurrence of stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Chest. 2015;148:711–21 [PMID: 25836013]. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-3005.

Salhia B, Trippel M, Pfaltz K, Cihoric N, Grogg A, Lädrach C, Zlobec I, Tapia C. High tumor budding stratifies breast cancer with metastatic properties. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:363–71 [PMID: 25779101]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3333-3.

Shimizu S, Miyazaki A, Sonoda T, Koike K, Ogi K, Kobayashi JI, Kaneko T, Igarashi T, Ueda M, Dehari H, Miyakawa A, Hasegawa T, Hiratsuka H. Tumor budding is an independent prognostic marker in early stage oral squamous cell carcinoma: with special reference to the mode of invasion and worst pattern of invasion. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195451 [PMID: 29672550]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195451.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There is no funding or conference presentation information to disclose

Availability of data and materials

Additional datasets from the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD, the first author, drafted the manuscript. OA contributed to the design of the writing and support of the literature and is the corresponding author. EO contributed to the pathological evaluation and support of the literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Ethics/institutional review board approval of research Faculty of Medicine, Acibadem University, Istanbul, Turkey. Number: 2018-19/16 Date: 06.12.2018

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this original research. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Demir, A., Alan, O. & Oruc, E. Tumor budding for predicting prognosis of resected rectum cancer after neoadjuvant treatment. World J Surg Onc 17, 50 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1588-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1588-6