Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility, safety, and potential benefits of laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG) comparing with open gastrectomy (OG) in elderly population.

Methods

Studies comparing LG with OG for elderly population with gastric cancer, published between January 1994 and July 2015, were identified in the PubMed, Embase, and ISI Web of Science databases. Operative outcomes (intraoperative blood loss, operative time, and the number of lymph nodes harvested) and postoperative outcomes (time to first ambulation, time to first flatus, time to first oral intake, postoperative hospital stay, postoperative morbidity) were included and analyzed. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to assess the quality of the pooled study. A funnel plot was used to evaluate the publication bias.

Results

Seven studies totaling 845 patients were included in the meta-analysis. LG in comparison to OG showed less intraoperative blood loss (weighted mean difference (WMD) −127.47; 95 % confidence interval (CI) −202.79 to −52.16; P < 0.01), earlier time to first ambulation (WMD −2.07; 95 % CI −2.84 to −1.30; P < 0.01), first flatus (WMD −1.04; 95 % CI −1.45 to −0.63; P < 0.01), and oral intake (WMD −0.94; 95 % CI −1.11 to −0.77; P < 0.01), postoperative hospital stay (WMD −5.26; 95 % CI −7.58 to −2.93; P < 0.01), lower overall postoperative complication rate (odd ratio (OR) 0.39; 95 % CI 0.28 to 0.55; P < 0.01), less surgical complications (OR 0.47; 95 % CI 0.32 to 0.69; P < 0.01), medical complication (OR 0.35; 95 % CI 0.22 to 0.56; P < 0.01), incisional complication (OR 0.40; 95 % CI 0.19 to 0.85; P = 0.02), and pulmonary infection (OR 0.49; 95 % CI 0.26 to 0.93; P = 0.03). No significant differences were observed between LG and OG for the number of harvested lymph nodes. However, LG had longer operative times (WMD 15.73; 95 % CI 6.23 to 25.23; P < 0.01).

Conclusions

LG is a feasible and safe approach for elderly patients with gastric cancer. Compared with OG, LG has less blood loss, faster postoperative recovery, and reduced postoperative morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide, especially in East Asia [1–4]. Radical gastrectomy is the mainstay of the curative treatment for gastric cancer. As life expectancy has increased consistently, inevitably, an increasing number of aged people with gastric cancer are anticipated to undergo gastrectomy with the goal of radical treatment [5]. Characteristics of elderly patients such as declining physiological function and poor nutritional status, together with severe surgical traumas of radical gastrectomy, appear to result in higher postoperative morbidity, prolonged hospital stay, increasing financial burden, and even higher postoperative mortality. Approaches with less surgical traumas and milder acute inflammation response are urged.

Despite of controversy, laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG) has been developed as an innovation in the management of gastric cancer [6–8]. Many previous studies including several randomized clinical trials on LG have referred to its surgical benefits of less invasiveness [9–12]. In addition, recent advances in laparoscopic instruments and accumulating surgical experience impelled surgeons to apply LG in locally advanced gastric cancer. Growing evidences have suggested LG was able to achieve equivalent oncological outcomes as open gastrectomy (OG) in both early and advanced gastric cancer [13, 14]. Though concerning the pneumoperitoneum, LG has been gradually performed in elderly population. Researches specifically studying the application of LG in elderly population are limited. Hence, we comprehensively collected relevant evidences and conducted this systematic review with meta-analysis to assess the feasibility, safety, and potential benefits of LG in elderly population.

Methods

Search strategy

Articles published from January 1994 to July 2015 were searched in the PubMed, Embase, and ISI Web of Science databases. The search strategy was performed using the following terms: “gastric cancer,” “gastric adenocarcinoma,” “gastric neoplasms,” “laparoscopy,” “laparoscopic,” “elderly,” “old,” and “aged.” All abstracts retrieved from the electronic databases were screened. Then, the full texts were retrieved when abstracts were relevant. The references of all relevant articles were also manually searched for potentially relevant studies.

Study selection

Eligibility criteria included the following: (1) histologically confirmed gastric cancer; (2) published studies comparing LG with OG for gastric cancer; (3) inclusion of elderly patients; and (4) availability of data on information of at least three outcome measures. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) recurrent gastric cancer; (2) hand-assisted surgery or robotic surgery; (3) combined with other malignancies; (4) abstracts presented at meetings, review articles, case report, or letters; and (5) palliative gastrectomy. If more than one study of a single institution existed, the study with the most recent or the most informative data was included unless the relevant outcomes were only published in earlier version.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted and checked data using a standard form. Disagreements in data extraction were resolved through discussion and consensus of the study team. The following data were extracted from each study: study name, study period, sample size, age, body mass index (BMI), comorbidity, extent of lymph node dissection, method of gastrectomy, tumor size, tumor location, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, number of harvested lymph nodes, time to first flatus, time to first oral intake, length of postoperative hospital stay, and postoperative complications. The qualities of studies were evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) [15]. Studies with a score equal to or higher than six stars were considered methodologically sound.

Statistical methods

Dichotomous variables were evaluated by using odds ratio (OR) with a 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI), and continuous variables were analyzed using the weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95 % CI. If the study provided medians and ranges instead of means and standard deviations (SDs), the means and SDs were calculated using the method described by Hozo et al. [16]. Heterogeneity was evaluated by Cochran’s Q-statistic and I 2 [17]. If data was not significantly heterogeneous (P > 0.05 or I 2 < 50 %), the pooled effects were calculated using a fixed model [18]. Otherwise, the pooled effects were calculated using a random-effects model [19]. Publication bias was evaluated visually using a funnel plot. All data were analyzed using the Review Manager Version 5.0 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study characteristics

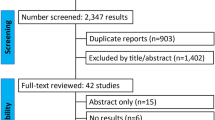

The search strategy initially identified 2069 studies. After exclusion of irrelevant studies, 20 potentially relevant articles were obtained for assessment. Thirteen studies were excluded due to non-comparative studies, did not compare LG with OG, and including palliative gastrectomy cases. Finally, seven studies (three from Japan and four from China) published between 2004 and 2015 were included [20–26]. The PRISMA flowchart of literature review is shown in Fig. 1. The characteristics of these seven studies are summarized in Table 1. A total of 845 patients from East Asia were pooled in this meta-analysis: 422 in the LG group and 423 in the OG group. Patients more than 70 years old were categorized as elderly patients in four studies [20, 21, 24, 25], more than 65 years old in two studies [22, 23], and more than 75 years old in one study [26]. Patients from Japan mostly suffered early gastric cancer and underwent D1 or D1+ lymphadenectomy, while the majority of patients from China suffered advanced gastric cancer and underwent D2 lymphadenectomy. Three studies compared the prognostic outcomes and demonstrated no significant difference between LG and OG. Oncological outcomes of included studies are showed in Table 2. All seven studies were methodologically sound with no less than six stars (Table 3).

Operative outcomes

All seven pooled studies reported the operation time and intraoperative blood loss. Our meta-analysis suggested LG was associated with a reduction in intraoperative blood loss (WMD −127.47; 95 % CI −202.79 to −52.16; P < 0.01; Fig. 2a), although longer operation time was also observed (WMD 15.73; 95 % CI 6.23 to 25.23; P < 0.01; Fig. 2b). In addition, LG achieved equivalent lymph nodes compared with OG (WMD 1.00; 95 % CI −0.24 to 2.24; P = 0.11; Fig. 2c).

Postoperative outcomes

Patients in the LG group have earlier time to ambulation than those in the OG group by about 2 days (WMD −2.07; 95 % CI −2.84 to −1.30; P < 0.01; Fig. 3a). The LG group also had favored time to first flatus (WMD −1.04; 95 % CI −1.45 to −0.63; P < 0.01; Fig. 3b), time to resume oral intake (WMD −0.94; 95 % CI −1.11 to −0.77; P < 0.01; Fig. 3c), and postoperative hospital length (WMD −5.26; 95 % CI −7.58 to −2.93; P < 0.01; Fig. 3d).

The postoperative complications were recorded in all studies. The LG group had lower overall postoperative complication rate than the OG group (OR 0.39; 95 % CI 0.28 to 0.55; P < 0.01; Fig. 4a). In detail, LG comparing with OG showed reduced surgical complications (OR 0.47; 95 % CI 0.32 to 0.69; P < 0.01; Fig. 4b) and medical complication (OR 0.35; 95 % CI 0.22 to 0.56; P < 0.01; Fig. 4c). Further analysis also revealed that the LG group was associated with lower incisional complication (OR 0.40; 95 % CI 0.19 to 0.85; P = 0.02; Fig. 4d) and pulmonary infection rate (OR 0.49; 95 % CI 0.26 to 0.93; P = 0.03; Fig. 4e).

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by exclusion of the highest weighted study in each pooled analysis. These exclusions did not alter the results obtained in cumulative analyses. Funnel plot based on the overall postoperative complication was performed to assess publication bias. No significant publication bias was detected by visual inspection of the funnel plot in which the pooled studies were almost symmetrical and none of them was outside the 95 % CI (Fig. 5).

Discussion

With continuing growth of the elderly population, more elderly patients undergo gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Generally, the elderly patients are usually accompanied with impaired physiological function, clinically presenting as a higher incidence of comorbidities, which is likely to have adverse effects on perioperative outcomes and result in postoperative complications or even death [27, 28]. Lee et al. reported postoperative morbidity including systemic complication, and severe complication showed higher tendency with increased age [29]. Minimally invasive and enhanced recovering approaches are urged for this special population. Surgeons have applied laparoscopic technique in nearly all abdominal surgeries, including gastric cancer. However, convincing evidences remain lacking which impels us to conduct this meta-analysis. We found that patients who underwent LG were associated with less blood loss, faster recovery, and less postoperative morbidity as compared with its open counterpart.

Postoperative complications of gastrectomy result in several events, including longer hospital stays, increased medical expenses, delayed adjuvant chemotherapy, and oncological outcomes. Kubota et al. revealed that postoperative complications that can cause prolonged inflammation result in shorter overall survival (OS) and worse disease-specific mortality even if the tumor is resected curatively [30]. One of the main concerns with LG in elderly population is the possibility of cardiopulmonary complication related to pneumoperitoneum. Whereas our meta-analysis found that patients who underwent LG have lower risk of medical complication, especially the postoperative pneumonia, which was in conformity with several reports [31]. Milder pain associated with LG encourages patients to expectorate and to start postoperative activity earlier. Suzuki et al. also reported that the cardiopulmonary adverse effects due to pneumoperitoneum were transitory and normalized during the intraoperative period and were acceptable even among decrepit elderly patients having cardiopulmonary disease [26]. Avoidance of the large incision and completing the gastrointestinal reconstruction with or without a mini-laparotomy reduces the risk of wound infection. Smaller incision and meticulous manipulation helped to remit the postoperative pain and reduce surgical stress. Okholm et al. reported that LG attenuates the postoperative immune response compared to open surgery [32]. From this point, patients who underwent LG were able to have enhanced bowel recovery. Our study also found that the LG group had shorter bedbound time, time to first flatus, time to resume oral intake, and length of hospital stay.

In accordance with previous studies [33–35], the LG group had a longer operation time by about 15 min in our study. Longer operation time was considered as an adverse factor of surgical outcomes. Miki et al. reported that patients with extended operation time had higher risk of severe postoperative complication [36]. Owing to the introduction of automatic-sewn techniques and avoidance of open and closure of conventional surgical incision as OG, operation time of LG gradually reduced in recent years. Several large sample studies have indicated LG achieved similar or even shorter operation time compared with OG when surgeons have passed the learning curve [37–39], suggesting it may be a drawback of LG no longer in the future.

As a general benefit of laparoscopic techniques, the LG group was favored with less intraoperative blood loss. High heterogeneity between groups was observed in our study, which was likely to relate with the diversity of surgeons’ experience and methods to estimate the blood loss. This notable benefit mainly attributed to the nature of laparoscopic techniques. Magnified operation view facilitates meticulous manipulation. On the other hand, using harmonic instruments contribute to dissecting vessels around the stomach precisely and efficiently [40]. Less blood loss during LG may help maintain cardiopulmonary function stability and reduced the subsequently potential risk of postoperative morbidity.

Because none of the pooled studies reported the hazard ratios and its 95 % CI and the Kaplan-Meier curves in several pooled studies were of poor quality, we did not analyze the pooled 5-year OS rate. However, all three pooled studies reported that a 5-year OS rate of LG was comparable with OG. Though indirectly, the number of retrieved lymph nodes is usually used as an indicator of the oncologic adequacy of gastrectomy. In our study, no significant difference of retrieved lymph nodes was observed between two groups. The number of retrieved lymph nodes in both the LG and OG group was more than 15 as recommended [41], which was considered to be oncologically acceptable. The extent of lymphadenectomy remains controversial, though D2 lymphadenectomy has been reported to yield better prognostic outcomes [42–44]. In elderly patients, surgeons are usually reluctant to perform D2 resection to avoid major postoperative complications. Takeshita et al. reported that radical lymph node dissection for elderly patients may reduce life expectancy, especially in stage I and II patients [27]. They also recommend that R0 resection with at least limited lymph node dissection according to the Japanese guideline should be considered as the first choice of treatment for this population. It was actually reported that there are no significant benefits of D2 over D1 for patients >70 years old (5-year OS 19.8 % for D2 and 23.1 % for D1; P > 0.05) [45]. The average life expectancy of elderly patients is short, which may obscure the value of D2 lymphadenectomy. Therefore, more well-designed studies need to evaluate the proper extent of lymph node dissection in elderly patients.

Our studies also had some limitations, which should be taken into consideration before clinical practices. First, there was no randomized controlled study included in this study. Potential bias may exist in the selection of patients into the LG and OG group. Second, heterogeneity in studies with different cutoff age of elderly patients may also decrease the plausibility of the results. Third, the overall sample size of our study remained limited, and the inclusion of some small sample size studies or the method to estimate means and SDs described by Hozo may also result in bias. Fourth, this meta-analysis only included studies published in English or Chinese which may omit some important studies in other languages. Other biases may lie in that all pooled studies were from East Asia while no article comparing the LG and OG from other regions was retrieved. Nevertheless, Singh et al. reported that Western elderly patients could also undergo laparoscopic gastrectomy with low postoperative morbidity rate (3/20), suggesting the superior safety of LG in elderly patient [46].

Conclusions

In conclusion, LG is a feasible and safe approach for elderly patients with gastric cancer. Compared with its open counterpart, LG has less blood loss, faster postoperative recovery, and reduced postoperative morbidity.

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108.

Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zhao P, Li G, Wu L, He J. Report of incidence and mortality in China cancer registries, 2009. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:10–21.

Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Levi F, Praud D, Ferlay J, Negri E, Malvezzi M, La Vecchia C. Recent patterns in gastric cancer: a global overview. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:666–73.

Matsuda T, Marugame T, Kamo K, Katanoda K, Ajiki W, Sobue T. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2006: based on data from 15 population-based cancer registries in the monitoring of cancer incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:139–47.

Saif MW, Makrilia N, Zalonis A, Merikas M, Syrigos K. Gastric cancer in the elderly: an overview. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:709–17.

Chen K, Mou YP, Xu XW, Pan Y, Zhou YC, Cai JQ, Huang CJ. Comparison of short-term surgical outcomes between totally laparoscopic and laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a 10-y single-center experience with meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 2015;194:367–74.

Mochiki E, Kamiyama Y, Aihara R, Nakabayashi T, Asao T, Kuwano H. Laparoscopic assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: Five years’ experience. Surgery. 2005;137:317–22.

Lee SI, Choi YS, Park DJ, Kim HH, Yang HK, Kim MC. Comparative study of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy and open distal gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:874–80.

Haverkamp L, Brenkman HJF, Seesing MFJ, Gisbertz SS, Henegouwen M, Luyer MDP, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Wijnhoven BPL, van Lanschot JJB, de Steur WO. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer, a multicenter prospectively randomized controlled trial (LOGICA-trial). BMC Cancer. 2015;15:556.

Lin J-X, Huang C-M, Zheng C-H, Li P, Xie J-W, Wang J-B, Lu J, Chen Q-Y, Cao L-L, Lin M. Surgical outcomes of 2041 consecutive laparoscopic gastrectomy procedures for gastric cancer: a large-scale case control study. Plos One. 2015;10:e0114948.

Sun JF, Li J, Wang JW, Pan T, Zhou J, Fu XH, Zhang SZ. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on laparoscopic gastrectomy vs. open gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 2012;59:1699–705.

Huscher CGS, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, Ponzano C. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer—five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232–7.

Sugita H, Kojima K, Inokuchi M, Kato K. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Surg Res. 2015;193:190–5.

Kim HH, Han SU, Kim MC, Hyung WJ, Kim W, Lee HJ, Ryu SW, Cho GS, Song KY, Ryu SY. Long-term results of laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a large-scale case-control and case-matched Korean multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:627–33.

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses, http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–48.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

Yasuda K, Sonoda K, Shiroshita H, Inomata M, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in the elderly. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1061–5.

Mochiki E, Ohno T, Kamiyama Y, Aihara R, Nakabayashi T, Asao T, Kuwano H. Laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in young and elderly patients. World J Surg. 2005;29:1585–91.

Meng CY, Lin JX, Huang CM, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB. Laparoscopy-assisted radical gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer in the elderly. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2012;15:152–6.

Hu JH, Yang DS, Zheng L, Li SJ, Wang CY, Ren XQ. Study on the application of laparoscopy-assisted radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer in the elderly. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2013;16:1092–5.

Li H, Han X, Su L, Zhu W, Xu W, Li K, Zhao Q, Yang H, Liu H. Laparoscopic radical gastrectomy versus traditional open surgery in elderly patients with gastric cancer: benefits and complications. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:530–4.

Qiu JF, Yang B, Fang L, Li YP, Shi YJ, Yu XC, Zhang MC. Safety and efficacy of laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer in the elderly. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:3562–7.

Suzuki S, Nakamura T, Imanishi T, Kanaji S, Yamamoto M, Kanemitsu K, Yamashita K, Sumi Y, Tanaka K, Kuroda D, Kakeji Y. Carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum led to no severe morbidities for the elderly during laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1548–54.

Takeshita H, Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Surgical outcomes of gastrectomy for elderly patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:2891–8.

Huang CM, Tu RH, Lin JX, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lu J, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M. A scoring system to predict the risk of postoperative complications after laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer based on a large-scale retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e812.

Lee KG, Lee HJ, Yang JY, Oh SY, Bard S, Suh YS,Kong SH, Yang HK. Risk factors associated with complication following gastrectomy for gastric cancer: retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data based on the Clavien-Dindo system. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1269–77.

Kubota T, Hiki N, Sano T, Nomura S, Nunobe S, Kumagai K, Aikou S, Watanabe R, Kosuga T, Yamaguchi T. Prognostic significance of complications after curative surgery for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:891–8.

Cai J, Wei D, Gao CF, Zhang CS, Zhang H, Zhao T. A prospective randomized study comparing open versus laparoscopy-assisted D2 radical gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer. Dig Surg. 2011;28:331–7.

Okholm C, Goetze JP, Svendsen LB, Achiam MP. Inflammatory response in laparoscopic vs. open surgery for gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1027–34.

Qiu J, Pankaj P, Jiang H, Zeng Y, Wu H. Laparoscopy versus open distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:1–7.

Wang W, Chen K, Xu XW, Pan Y, Mou YP. Case-matched comparison of laparoscopy-assisted and open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3672–7.

Cheng Q, Pang TC, Hollands MJ, Richardson AJ, Pleass H, Johnston ES, Lam VW. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open distal gastrectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1087–99.

Miki Y, Tokunaga M, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Terashima M. Perioperative risk assessment for gastrectomy by surgical Apgar score. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2601–7.

Huang C, Lin M, Chen Q, Lin J, Zheng C, Li P, Xie J, Wang J, Lu J, Chen T, Yang X. A modified intracorporeal Billroth-I anastomosis after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a safe and feasible technique. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:247.

Lee IS, Kim TH, Kim KC, Yook JH, Kim BS. Modified techniques and early outcomes of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy with side-to-side esophagojejunostomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:876–80.

Lee HH, Song KY, Lee JS, Park SM, Kim JJ. Delta-shaped anastomosis, a good substitute for conventional Billroth I technique with comparable long-term functional outcome in totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2545–52.

Sun ZC, Xu WG, Xiao XM, Yu WH, Xu DM, Xu HM, Gao HL, Wang RX. Ultrasonic dissection versus conventional electrocautery during gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:527–33.

Ajani JA, Bentrem DJ, Besh S, D'Amico TA, Das P, Denlinger C,Fakih MG, Fuchs CS, Gerdes H, Glasgow RE, et al. Gastric cancer, version 2.2013: featured updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:531–46.

Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:439–49.

Kasakura Y, Mochizuki F, Wakabayashi K, Kochi M, Fujii M, Takayama T. An evaluation of the effectiveness of extended lymph node dissection in patients with gastric cancer: a retrospective study of 1403 cases at a single institution. J Surg Res. 2002;103:252–9.

Edwards P, Blackshaw GR, Lewis WG, Barry JD, Allison MC, Jones DR. Prospective comparison of D1 vs modified D2 gastrectomy for carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1888–92.

Liang YX, Deng JY, Guo HH, Ding XW, Wang XN, Wang BG, Zhang L, Liang H. Characteristics and prognosis of gastric cancer in patients aged >/= 70 years. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6568–78.

Singh KK, Rohatgi A, Rybinkina I, McCulloch P, Mudan S. Laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: early experience among the elderly. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1002–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JFW and JJZ designed the study. JFW wrote the manuscript. SZZ, NYZ, and JFW performed the literature review, extraction of the data, and analysis of the pooled data. ZYW, JYF, and LPY revised the manuscript. JJZ reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Jf., Zhang, Sz., Zhang, Ny. et al. Laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for elderly patients with gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Onc 14, 90 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-0859-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-016-0859-8