Abstract

Background

Recently, a preoperative systemic inflammatory response has been reported to be a prognostic factor in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC). However, the prognostic significance of a systemic inflammatory response in the early stage after surgery in patients with CRC is unknown. The aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate the prognostic significance of a postoperative systemic inflammatory response in patients with CRC.

Methods

Two hundred and fifty-four patients who underwent potentially curative surgery for stage II/III CRC were enrolled in this study. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate the relationship between the prognosis and clinicopathological factors, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS), which were measured within two weeks before operation and at the first visit after leaving the hospital.

Results

The overall survival rates were significantly worse in the high preoperative NLR/preoperative GPS/postoperative NLR group. A multivariate analysis indicated that only preoperative GPS, postoperative NLR, and the number of lymph node metastases were independent prognostic factors for a poor survival.

Conclusions

The postoperative NLR is an independent prognostic factor in patients with CRC who underwent potentially curative surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. Although the surgical procedures and chemotherapy have improved, a large number of patients relapse after curative resection, and the mortality from colorectal cancer is still high. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the patients with a high possibility of recurrence, and various biomarkers associated with poor survival have been examined.

Recently, the systemic inflammatory response has been recognized to correlate with the progression of the tumor and the prognosis of various types of cancer, including CRC. The markers of the systemic inflammatory response, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [2–4], serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level [5, 6], and Glasgow prognostic score (GPS) [4, 7, 8] have been reported to be associated with the prognosis in patients with CRC. However, most of these reports investigated the preoperative status, and there have been no reports on the relationship between the systemic inflammatory response in the early stage after surgery and the prognosis after potentially curative resection of CRC. The aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate the prognostic significance of the postoperative systemic inflammatory response in patients with CRC.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed a database of 254 patients who underwent potentially curative surgery for stage II/III CRC at the Department of Surgical Oncology of Osaka City University between 2006 and 2011. Curative surgery was defined as the absence of any gross residual tumor tissue in the surgical bed, with a surgical resection margin that was pathologically negative for tumor invasion. Patients who received preoperative therapy or who had either bowel obstruction or perforation due to their primary tumor were excluded from the analysis.

The patient population consisted of 139 males and 115 females, with a median age of 60 years (range, 26 to 86). One hundred and thirty-one patients had tumors located in the colon, and 123 had tumors located in the rectum. One hundred and seventy-eight patients received monotherapy using an oral pro-drug based on 5-FU, such as capecitabine, while 30 patients received combination therapy with 5-FU and oxaliplatin, such as 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CapeOX) (Table 1).

The postoperative systemic inflammatory response was measured at the first visit after leaving the hospital. The date of the first visit was set to occur two to three weeks after the patient left the hospital. The median (interquartile range) period from the operation until the first visit after leaving the hospital was 29 (23–36) days. The NLR was calculated from a blood sample by dividing the absolute neutrophil count by the absolute lymphocyte count. According to the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve, we set 2.5 as the cut-off value for the preoperative NLR (the sensitivity was 51.9 % and the specificity was 64.2 %) (Fig. 1a) and classified the patients into high preoperative NLR (≥2.5) and low preoperative NLR (<2.5) groups. Moreover, according to the ROC curve, we also set 3.0 as the cut-off value for the postoperative NLR (the sensitivity was 35.7 % and the specificity was 87.3 %) (Fig. 1b) and classified the patients into high postoperative NLR (≥3.0) and low-postoperative NLR (<3.0) groups.

a Receiver-operating characteristic-curve analysis of the preoperative NLR. Area under the curve = 0.618, 95 % confidence interval = 0.502–0.735, p = 0.053. b Receiver-operating characteristic-curve analysis of the postoperative NLR. Area under the curve = 0.680, 95 % confidence interval = 0.573–0.787, p = 0.002

We defined the GPS according to the previous reports as follows [9]: the GPS consists of the combination of an elevated CRP (≥1 mg/dl) and hypoalbuminemia (<3.5 g/dl). Patients with both abnormalities were allocated a GPS of 2. Patients with only one of these abnormalities were allocated a GPS of 1. Patients with normal values for both were allocated a GPS of 0. The patients with a GPS of 1 or 2 were classified into the high GPS group, and those with a GPS of 0 were classified into the low-GPS group.

We then examined the correlations between the clinicopathological parameters, including the postoperative NLR/GPS and the prognosis for survival. All patients were followed up regularly with physical and blood examinations and mandatory screening using colonoscopy and computed tomography until May 2014 or death. Among the total 254 patients, 86 developed recurrent disease and 42 patients died.

The resected specimens were pathologically classified according to the seventh edition of the Union for International Cancer Control TNM classification of malignant tumors [10]. The significance of the correlations between the systemic inflammatory response and the clinicopathological characteristics was analyzed by the χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, and t-test. The duration of survival was calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in the survival curves were assessed with the log-rank test. A multivariate analysis was performed according to the Cox proportional hazards model. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS software package for Windows (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Statistical significance was set at a value of p <0.05.

Results

The preoperative/postoperative indicators of a systemic inflammatory response are shown in Table 1. The distribution of patients based on the indicators of a systemic inflammatory response is shown in Table 2.

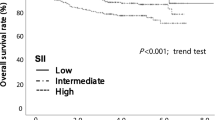

As for the preoperative inflammatory status, an assessment of the prognosis showed that the overall survival rates were significantly worse in the high preoperative NLR/GPS group (NLR, p = 0.0388; GPS, p = 0.0028) (Fig. 2). Moreover, as for the postoperative inflammatory status, the overall survival rates were significantly worse in the high postoperative NLR group (p = 0.0006), while there was no relationship between the postoperative GPS and mortality (Fig. 3). The postoperative NLR had a significant relationship with the amount of blood loss during the operation and the length of the operation and tended to correlated with gender, while there was no relationship between the postoperative NLR and other factors including preoperative NLR (Table 3). The postoperative GPS had a significant relationship with lymphatic involvement, the number of lymph node metastasis, the preoperative CA19-9 level, and the preoperative GPS (Table 3). With regard to the relationships between the postoperative systemic inflammatory response and the sub-classification of the postoperative infectious complications, neither NLR nor GPS showed a significant relationship with the sub-classification of the postoperative infectious complications (Table 4).

a The overall survival according to the preoperative NLR. The overall survival rates were significantly worse in the high preoperative NLR group (p = 0.0388). b The overall survival according to the preoperative GPS. The overall survival rates were significantly worse in the high preoperative GPS group (p = 0.0028)

The correlations between the overall survival and various clinicopathological factors are shown in Table 5. According to a univariate analysis, the overall survival had significant relationships with the postoperative NLR, the preoperative NLR, the preoperative GPS, age, the tumor depth, histological type, venous involvement, and the number of lymph node metastases. However, a multivariate analysis indicated that only the preoperative GPS, the postoperative NLR, and the number of lymph node metastases were independent risk factors for mortality.

We categorized the patients into four groups according to the combination of their preoperative and postoperative NLR. Patients with the low preoperative and postoperative NLR categorized into group A. Patients with the low preoperative NLR and the high postoperative NLR were categorized into group B. Patients with the high preoperative NLR and the low-postoperative NLR were categorized into group C. Patients with the high preoperative and postoperative NLR categorized into group D. The patients in group A exhibited a better prognosis compared to the other groups (AvsB, p = 0.0124; AvsC, p = 0.0202; AvsD, p = 0.0031), while there was no significant difference between groups B, C, and D with regard to survival (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the correlations between the high postoperative NLR and poor survival in patients with colorectal cancer who underwent potentially curative surgery. When considering the prognosis of patients with malignant tumors, the TNM-classification criteria [10], which are factors related to the tumor and accurately reflect the prognosis, have been widely used. Recently, the prognostic significance of the factors related to the host based on the systemic inflammatory response, such as the NLR, CRP, and GPS in patients with CRC, has been reported [2–8]. However, most of the previous reports focused on the preoperative status, and there have been only a few reports which focused on the prognostic significance of the postoperative systemic inflammatory response. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the prognostic significance of the systemic inflammatory response in the early stage after surgery.

Neutrophils play a key role in tumor progression, producing a number of ligands that induce tumor cell proliferation and invasion, and promoting tumor vascularization by releasing proangiogenic chemokines and other factors [11, 12]. As the main cause of recurrence after potentially curative operation may be the growth of micrometastases which had been established prior to resection [13], and because the continuous systemic inflammatory response creates a favorable environment for micrometastatic growth, a persistently elevated level of neutrophils after surgery is considered to correlate with the development of recurrence. In contrast, lymphocytes, which play an important role in anti-tumor immunity, are a factor related to the immune system of the host [14]. The absolute lymphocyte count is assumed to reflect the degree of responsiveness of a cancer patient’s whole immune system [15]. Therefore, a decrease of lymphocytes is considered to correlate with recurrence. Taken together, a persistently high NLR after surgery means the continuation of an environment that is favorable for recurrence. Thus, the postoperative status, as well as the preoperative status of the host, is important when considering the prognosis.

The mechanism of the persistent activation of the systemic inflammatory response after surgery remains unclear. In this study, a high postoperative NLR was significantly correlated with the amount of blood loss during the operation and the length of the operation. These results suggested that a high postoperative NLR might be associated with higher surgical stress. However, we could not conclude that the main cause of the persistent elevation of the systemic inflammatory response after the operation was surgical stress itself, because other than the parameters of blood loss during the operation and the length of the operation, there are no useful markers for evaluating the degree of surgical stress, and the markers on their own were not sufficient to perform an evaluation. On the other hand, the postoperative NLR had no association with the factors related to the tumor, although the preoperative NLR was previously reported to correlate with several factors related to the tumor [2]. Moreover, the postoperative NLR had no relationship with the presence of postoperative infectious complications, even when performing the additional analyses regarding the degree and type of postoperative infectious complications. There were some patients with normal inflammatory marker levels at the first visit after leaving the hospital who developed postoperative infectious complications, while some patients with high postoperative systemic inflammatory marker levels were discharged without postoperative complications. The postoperative infectious complications may not be the main cause of the high postoperative systemic inflammatory response at the first visit after leaving the hospital. Aside from surgical stress and the postoperative infectious complications, the response of the host to the micrometastatic lesion has been reported to cause a persistently high postoperative systemic inflammatory response [16]. However, it is questionable whether the response to the micrometastatic lesion and the response to the primary tumor are equivalent.

Our results were in line with a study by Guthrie et al., which reported that the persistent elevation of the systemic inflammatory response after surgery was correlated with poor survival [16]. However, we obtained different results in relation to the superiority of the postoperative inflammatory markers. We found postoperative NLR to be superior to the postoperative GPS, while Guthrie et al. reported the opposite [16]. Moreover, the timing of the valuation of the postoperative inflammatory response differed between this study and the previous report. In this study the postoperative inflammatory response was evaluated in the early stage after operation (approximately 1–2 months after surgery, when we decided the regimen of adjuvant chemotherapy), while in the previous report, the inflammatory response was evaluated at 3–6 months after surgery [16].

There are some limitations associated with this study. First, we evaluated a relatively small number of patients. Second, the criteria for the first visit after leaving the hospital were not uniform because this study was a retrospective study. Third, the appropriate timing for the evaluation of the postoperative systemic inflammatory response to predict the survival was unknown. Fourth, the mechanism of the persistent elevation of the postoperative inflammatory response remains unclear. A large, prospective study should therefore be performed to confirm our findings.

Conclusions

In this study, the postoperative NLR was demonstrated to correlate with a poor survival as well as the preoperative NLR and the postoperative NLR were investigated to be an independent prognostic factor for poor survival. Therefore, not only the preoperative status of the host, but also the postoperative status of the host, is important when considering the prognosis.

Abbreviations

- CA19-9:

-

carbohydrate antigen 19–9

- CEA:

-

carcinoembryonic antigen

- CapeOX:

-

capecitabine plus oxaliplatin

- CRC:

-

colorectal cancer

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- FOLFOX:

-

5-fluorouracil/leucovorin plus oxaliplatin

- GPS:

-

Glasgow prognostic score

- NLR:

-

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- ROC:

-

receiver-operating characteristic

References

Edwards BK, Noone AM, Mariotto AB, Simard EP, Boscoe FP, Henley SJ, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1290–314.

Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Noda E, Ohtani H, Nishiguchi Y, et al. A high preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with poor survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:3291–4.

Chiang SF, Hung HY, Tang R, Changchien CR, Chen JS, You YT, et al. Can neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predict the survival of colorectal cancer patients who have received curative surgery electively? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1347–57.

Maeda K, Shibutani M, Otani H, Nagahara H, Sugano K, Ikeya T, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer who undergo palliative resection of asymptomatic primary tumors. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:5567–73.

McMillan DC, Canna K, McArdle CS. Systemic inflammatory response predicts survival following curative resection of colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:215–9.

Chung YC, Chang YF. Serum C-reactive protein correlates with survival in colorectal cancer patients but is not an independent prognostic indicator. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:369–73.

Sugimoto K, Komiyama H, Kojima Y, Goto M, Tomiki Y, Sakamoto K. Glasgow prognostic score as a prognostic factor in patients undergoing curative surgery for colorectal cancer. Dig Surg. 2012;29:503–9.

Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Horie T, Kubota K. Inflammation-based prognostic score is a novel predictor of postoperative outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1047–51.

Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dagg K, Scott HR. A prospective longitudinal study of performance status, an inflammation-based score (GPS) and survival in patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1834–6.

Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumors, 7th edn. UICC International Union against cancer. 2009.

Neal CP, Mann CD, Sutton CD, Garcea G, Ong SL, Steward WP, et al. Evaluation of the prognostic value of systemic inflammation and socioeconomic deprivation in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastasis. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:56–64.

Terzic J, Grivennikov S, Karin E, Karin M. Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2101–14.

Fidler IJ, Kripke ML. Metastasis results from preexisting variant cells within a malignant tumor. Science. 1977;197:893–5.

Kitayama J, Yasuda K, Kawai K, Sunami E, Nagawa H. Circulating lymphocyte is an important determinant of the effectiveness of preoperative radiotherapy in advanced rectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:64.

Cézé N, Thibault G, Goujon G, Viguier J, Watier H, Dorval E, et al. Pre-treatment lymphopenia as a prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68:1305–13.

Guthrie GJ, Roxburgh CS, Farhan-Alanie OM, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Comparison of the prognostic value of longitudinal measurements of systemic inflammation in patients undergoing curative resection of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:24–8.

Acknowledgements

The funding agency had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication. We thank Brian Quinn who provided medical-writing service on behalf of JMC Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MS and KM designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. HN, HO, YI, TI, and KS collected the clinical data. KH designed the study and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Shibutani, M., Maeda, K., Nagahara, H. et al. The prognostic significance of a postoperative systemic inflammatory response in patients with colorectal cancer. World J Surg Onc 13, 194 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0609-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0609-3