Abstract

Background

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SNB)-oriented stepwise treatment under local anesthesia has been performed in the outpatient-ambulatory setting in patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy (NAT). We retrospectively reviewed our preliminary experience of ambulatory SNB in breast cancer patients scheduled to undergo NAT to evaluate the usefulness and feasibility of this method as a minimally invasive, stepwise treatment protocol.

Methods

We retrospectively identified 56 patients with breast cancer without obvious nodal involvement who were scheduled to receive NAT before breast surgery. SNB was performed under local anesthesia in an ambulatory outpatient setting before the initiation of NAT.

Results

The average number of removed sentinel lymph nodes was 1.9. Identification of the sentinel node was possible in all cases, and macrometastasis was observed in six cases (10.7%). Micrometastasis was observed in five cases, while isolated tumor cells were noted in six cases. There were no delays in the initiation of NAT as a result of complications of SNB.

Conclusions

This pilot study demonstrated the safety and feasibility of ambulatory SNB prior to NAT. Further studies are warranted to assess the strict indications, patient satisfaction, and medical economics of this procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SNB) in patients undergoing breast cancer surgery (BCS) is currently regarded as the standard minimally invasive strategy for managing clinically node-negative early breast cancer [1-5]. Neoadjuvant therapy (NAT) with chemo- or endocrine therapy is usually administered with the aim of enabling BCS or evaluating drug sensitivity in situ and is also regarded as a standard treatment for operable breast cancer [6,7]. Nodal status is a major factor determining the suitability of NAT. However, although SNB is considered to be an accurate method for evaluating axillary nodal status as an alternative to conservative axillary dissection, SNB after NAT is less reliable, particularly in patients in whom nodal involvement has been already detected prior to NAT [8,9]. Several reports have therefore suggested SNB prior to the initiation of NAT as a useful strategy for assessing axillary nodal status [10-13]. However, the application of SNB before NAT requires additional surgery and may result in delays in administering NAT. We have applied an ambulatory SNB protocol that allows NAT to be initiated based on an accurate histological diagnosis, including axillary nodal status, with minimal patient burden, thus enabling the immediate administration of NAT followed by BCS, with or without hospitalization, in accordance with the patient’s needs.

SNB can be performed safely and adequately under local anesthesia in the outpatient ambulatory setting, without hospitalization [14-20]. A pathological diagnosis can then be obtained from permanent preparations without the need for intraoperative evaluation of frozen sections, in which the latter process is associated with a 7% to 9% false-negative diagnosis rate [5,21-23]. Furthermore, axillary node dissection at surgery after NAT can be avoided in patients with pathologically proven sentinel lymph node (SN)-negative status [23-25].

In this study, we retrospectively reviewed our preliminary experience of ambulatory SNB in breast cancer patients scheduled to undergo NAT and evaluated the usefulness and feasibility of this method as an appropriate, minimally invasive, stepwise treatment protocol.

Methods

Patient characteristics

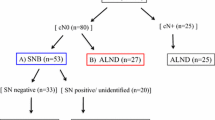

This study included 56 patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of invasive breast cancer following core needle biopsy (CNB) of the tumor between April 2009 and August 2013. All patients were scheduled for BCS following the administration of NAT. Patients with clinical T2 tumors in whom the absence of distant metastasis (M0) was confirmed by computed tomography (CT) and chest and abdomen and bone scintigraphy were enrolled. Patients with multiple tumors or with a previous history of surgery to the affected breast were excluded. Axillary nodal status was evaluated by palpation, CT, and ultrasonography, and patients with obvious node metastasis were also excluded to avoid unnecessary SNB. In these patients, lymph node metastasis was confirmed by either fine needle aspiration cytology or CNB of the affected nodes. Patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were provided with sufficient explanation of the stepwise treatment plan (Figure 1), including the procedure for ambulatory SNB with local anesthesia.

Treatment plan. We administered a series of treatments, including sentinel lymph node biopsy (SNB) under local anesthesia using ambulatory surgical procedures, followed by treatment with neoadjuvant therapy (NAT) based on the histological diagnosis, and subsequent breast cancer surgery (BCS). Ax: Axillary dissection.

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and carried out with the approval of the Ethical Review Board of Osaka City University (#926). Sufficient explanation was provided and written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects for their involvement in this study and for the storage and use of their data.

Surgical procedure

SNs were identified by a combination of radioisotope and dye methods [26]. For radioisotope examination, intradermal and subcutaneous 99mTc-phytic acid colloid 1 mCi (1 mL) was injected into the skin overlying the tumor and in the vicinity of the tumor the day before ambulatory SNB. Lymphoscintigraphy was performed 4 h after injection (Figure 2a). For dye examination, 1.0 mL of 1% lidocaine (not containing epinephrine) was added to 4.0 mL of indocyanine green (5 mg/mL) solution and injected intracutaneously in the areola of the affected side (Figure 2b). Approximately 10 min after injection, a skin incision (approximately 2 cm) was made in the axilla under local anesthesia with 0.5% to 1.0% lidocaine (containing 1:100,000 epinephrine) to identify the blue node [14]. A hand-held gamma probe was used to confirm the accumulation of radioactivity in the SN injected the day before SNB. No drainage tubes were placed. Pathological diagnosis of lymph node metastasis was made by slicing the entire SN into 2-mm-thick sections, and a detailed pathological diagnosis was obtained after conventional hematoxylin-eosin staining associated with touch imprint cytology [27,28], by a pathologist specializing in breast cancer. A positive diagnosis of SN metastasis as an indication for axillary clearance was defined as macrometastasis (i.e., tumor diameter >2 mm) in the SN. Micrometastasis (i.e., tumor diameter >0.2 mm, ≤2 mm, or <200 tumor cells) and isolated tumor cells (ITC, i.e., tumor diameter <0.2 mm or <200 tumor cells) were determined as negative indications [29].

NAT was generally recommended according to the intrinsic subtype of the primary tumor determined from the CNB sample, and axillary dissection was followed by BCS under general anesthesia within 4 weeks after the termination of NAT in SN-positive patients. BCS without axillary dissection was applied in SN-negative patients with or without hospitalization, according to patient preference. Subsequent radiotherapy with 50 to 60 Gy was administered to the residual mammary gland. Standard adjuvant therapy was administered if indicated, according to tumor subtype.

Results

All patients were female, with a median age of 59 (range 28 to 76) years. All SNB procedures were accomplished under local anesthesia without conversion to general anesthesia. No patients required hospitalization after SNB. There were no complications of ambulatory SNB requiring treatment, such as bleeding, infection, or lymphorrhea. The average number of excised SNs was 1.9 ± 1.1 (Table 1), and SN identification was possible in all cases.

Macrometastasis was detected in nine SNs in six patients (10.7%) (median diameter of metastatic lesion: 7.00 ± 2.20 mm). Micrometastasis was observed in ten SNs in five patients (median diameter: 0.60 ± 0.23 mm), and ITC was observed in ten SNs in six patients (median length: 0.14 ± 0.06 mm) (Table 2). NAT was performed according to each intrinsic subtype in all 56 patients after evaluating the histological status of the axillary lymph node metastasis. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) was conducted in 50 cases, resulting in 16 pathological complete responses (pCRs), 29 pathological partial responses (pPRs), and 5 cases of pathological stable disease (pSD). No cases of pathological progressive disease (pPD) were observed. Endocrine therapy was administered in six cases, resulting in no pCRs or pPDs, two cases of pPR, and four cases of pSD. BCS with axillary lymph node dissection was subsequently carried out as the second-phase surgical treatment in six SNB-positive patients, and further, axillary lymph node involvement was found in two of these six patients. Three additional nodes were found to be involved during axillary lymph node dissection after NAT in one patient with a single positive SN before NAT. Two additional metastatic nodes were found after NAT in another patient with three positive SNs before NAT. No additional axillary lymph node metastases were found in the other four patients who underwent axillary lymph node dissection (Table 3). BCS without axillary lymph node dissection was performed in the remaining 50 patients, including 7 patients under local anesthesia and 43 patients under general anesthesia. All patients remained alive without disease after a median follow-up period of 28 (range 3 to 52) months since BCS.

Discussion

The long-term prognosis of SNB patients is not affected by omitting axillary lymph node dissection, according to the results of the large-scale clinical trial NSABP B-32 [23]. SNB-oriented management of axillary lymph node dissection has thus become the standard, minimally invasive surgical strategy for controlling local disease and evaluating the pathological stage in patients with clinically node-negative, early breast cancer [1-5]. General anesthesia is contraindicated in some patients because of co-morbidities or a desire for ambulatory or short-stay surgery. We therefore developed an ambulatory SNB-oriented stepwise treatment strategy for such patients, as described in this study. Surgical methods for performing axillary lymph node dissection under local anesthesia have been reported previously, but the procedure can result in insufficient dissection because of unsatisfactory analgesia [19,20]. General anesthesia is therefore necessary for standard axillary lymph node dissection. SNB, however, can be carried out adequately and safely under local anesthesia, as described in the present study [14-18]. The existence and number of lymph node metastases are major prognostic factors [30,31], and obtaining an accurate diagnosis is mandatory for selecting patients who require additional systemic therapy after surgery. The false-negative rate of SNB for breast cancer is reported to be 7% to 9%, based on the results of meta-analyses [5,21-23]. The major reason for failure with respect to pathological misdiagnosis is thought to involve inadequate intraoperative tissue diagnosis associated with the limitations of tissue-preparation conditions during surgery using frozen specimens. Accordingly, non-definitive results have been demonstrated in 3% to 35% of cases [27,32-35]. These false-negative or indeterminate results may be avoided by standard pathological investigations using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples obtained by ambulatory SNB under local anesthesia.

The administration of NAT may affect the accuracy of SNB. Two large-scale studies demonstrated that performing SNB after NAC was not recommended in patients with apparent axillary lymph node involvement before treatment because of the lower detection and higher false-negative rates (SENTINA trial 14.2%, ACOSOG Z1071 trial 12.6%) of SNB after NAC [36,37]. At the same time, the authors suggested that patients without nodal disease may be candidates for SNB after NAC to avoid repeated surgery, delays in the initiation of NAC, and possible unnecessary axillary dissection in cases where total eradication of nodal disease has been achieved by NAC. Although controversies remain, SNB prior to NAT represents the most reliable way to evaluate axillary lymph node metastasis in patients scheduled for NAT. This procedure could help to predict the effect of NAT on the involved axillary lymph nodes by confirming pathological nodal involvement before NAT. Ambulatory SNB may also minimize the burden on the patient with respect to repeated surgery and delays in administering NAT, as demonstrated in the present study. Furthermore, intimate pathological review of the involved node may aid precise stratification of the patients for additional therapy and follow-up protocols after scheduled NAT and BCS. The current study did not evaluate the appropriate indications for SNB in patients in whom NAT failed, and this issue remains a concern. Patients demonstrating resistance to NAT may require changes in their treatment strategy from chemotherapy to surgical therapy to achieve sufficient disease control. Among such cases, even in those with previous negative results on SNB, simultaneous axillary lymph node dissection may be necessary to confirm negative node involvement and establish complete local control by salvage surgery.

According to the results of the recent Z0011 trial [38], clinicians must reconsider the need for complete axillary dissection in SNB-positive patients with clinically node-negative, early breast cancer scheduled for BCS with radiation and adjuvant therapy, as demonstrated in the present study. Furthermore, the present results also indicate the possibility of skipping SNB in such cases, though further investigations with longer observation periods are required. However, our SNB-oriented stepwise treatment protocol is likely to be beneficial in patients with clinically node-negative, early breast cancer, by offering a sufficient but minimally invasive treatment strategy based on accurate pathological staging.

Conclusions

This pilot study demonstrated the safety and feasibility of ambulatory SNB prior to NAT in patients with operable breast cancer. Future studies, including the determination of strict indications, assessments of patient satisfaction, and medical economics, are warranted.

Abbreviations

- BCS:

-

breast cancer surgery

- CNB:

-

core needle biopsy

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- ITC:

-

isolated tumor cell

- NAT:

-

neoadjuvant therapy

- pCR:

-

pathological complete response

- pPD:

-

pathological progressive disease

- pPR:

-

pathological partial response

- pSD:

-

pathological stable disease

- SN:

-

sentinel lymph node

- SNB:

-

sentinel lymph node biopsy

References

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1227–32.

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1233–41.

Schwartz GF, Giuliano AE, Veronesi U. Proceedings of the consensus conference on the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in carcinoma of the breast April 19 to 22, 2001, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Hum Pathol. 2001;2002(33):579–89.

Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, Luini A, Zurrida S, Galimberti V, et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:546–53.

Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, Luini A, Zurrida S, Galimberti V, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy as a staging procedure in breast cancer: update of a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:983–90.

Wolmark N, Wang J, Mamounas E, Bryant J, Fisher B. Preoperative chemotherapy in patients with operable breast cancer: nine-year results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;30:96–102.

Semiglazov VF, Semiglazov VV, Dashyan GA, Ziltsova EK, Ivanov VG, Bozhok AA, et al. Phase 2 randomized trial of primary endocrine therapy versus chemotherapy in postmenopausal patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:244–54.

Nason KS, Anderson BO, Byrd DR, Dunnwald LK, Eary JF, Mankoff DA, et al. Increased false negative sentinel node biopsy rates after preoperative chemotherapy for invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:2187–94.

Cohen LF, Breslin TM, Kuerer HM, Ross MI, Hunt KK, Sahin AA. Identification and evaluation of axillary sentinel lymph nodes in patients with breast carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1266–72.

Breslin TM, Cohen L, Sahin A, Fleming JB, Kuerer HM, Newman LA, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is accurate after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3480–6.

Mamounas EP, Brown A, Anderson S, Smith R, Julian T, Miller B, et al. Sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol B-27. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2694–702.

Newman EA, Sabel MS, Nees AV, Schott A, Diehl KM, Cimmino VM, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy performed after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is accurate in patients with documented node-positive breast cancer at presentation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2496–952.

Tausch C, Konstantiniuk P, Kugler F, Reitsamer R, Roka S, Pöstlberger S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy after preoperative chemotherapy for breast cancer: findings from the Austrian Sentinel Node Study Group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3378–83.

Kashiwagi S, Onoda N, Takashima T, Asano Y, Aomatsu N, Nakamura M, et al. Breast conserving surgery and sentinel lymph node biopsy under local anesthesia for breast cancer. J Cancer Ther. 2012;3:810–3.

Fenaroli P, Tondini C, Motta T, Virotta G, Personeni A. Axillary sentinel node biopsy under local anaesthesia in early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:1617–8.

Luini A, Gatti G, Frasson A, Naninato P, Magalotti C, Arnone P, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy performed with local anesthesia in patients with early-stage breast carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1157–60.

Smidt ML, Janssen CM, Barendregt WB, Wobbes T, Strobbe LJ. Sentinel lymph node biopsy performed under local anesthesia is feasible. Am J Surg. 2004;187:684–7.

Luini A, Caldarella P, Gatti G, Veronesi P, Vento AR, Naninato P, et al. The sentinel node biopsy under local anesthesia in breast cancer: advantages and problems, how the technique influenced the activity of a breast surgery department; update from the European Institute of Oncology with more than 1000 cases. Breast. 2007;16:527–32.

van Berlo CL, Hess DA, Nijhuis PA, Leys E, Gerritsen HA, Schapers RF. Ambulatory sentinel node biopsy under local anaesthesia for patients with early breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:383–5.

Athey N, Gilliam AD, Sinha P, Kurup VJ, Hennessey C, Leaper DJ. Day-case breast cancer axillary surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:96–8.

Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, Davies C, Elphinstone P, Evans E, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;366:2087–106.

Kim T, Giuliano AE, Lyman GH. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast carcinoma: a metaanalysis. Cancer. 2006;106:4–16.

Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Ashikaga T, et al. Technical outcomes of sentinel-lymph-node resection and conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer: results from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:881–8.

Lyman GH, Giuliano AE, Somerfield MR, Benson 3rd AB, Bodurka DC, Burstein HJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline recommendations for sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7703–20.

Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Costantino JP, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:927–33.

McMasters KM, Tuttle TM, Carlson DJ, Brown CM, Noyes RD, Glaser RL, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer: a suitable alternative to routine axillary dissection in multi-institutional practice when optimal technique is used. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2560–6.

Lee A, Krishnamurthy S, Sahin A, Symmans WF, Hunt K, Sneige N. Intraoperative touch imprint of sentinel lymph nodes in breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2002;96:225–31.

Khanna R, Bhadani S, Khanna S, Pandey M, Kumar M. Touch imprint cytology evaluation of sentinel lymph node in breast cancer. World J Surg. 2011;35:1254–9.

Houvenaeghel G, Nos C, Mignotte H, Classe JM, Giard S, Rouanet P, et al. Micrometastases in sentinel lymph node in a multicentric study: predictive factors of nonsentinel lymph node involvement–Groupe des Chirurgiens de la Federation des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cance. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1814–22.

Recht A, Pierce SM, Abner A, Vicini F, Osteen RT, Love SM, et al. Regional nodal failure after conservative surgery and radiotherapy for early-stage breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:988–96.

Vicini FA, Horwitz EM, Lacerna MD, Brown DM, White J, Dmuchowski CF, et al. The role of regional nodal irradiation in the management of patients with early-stage breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:1069–76.

Motomura K, Inaji H, Komoike Y, Kasugai T, Nagumo S, Noguchi S, et al. Intraoperative sentinel lymph node examination by imprint cytology and frozen sectioning during breast surgery. Br J Surg. 2000;87:597–601.

Llatjós M, Castellà E, Fraile M, Rull M, Julián FJ, Fusté F, et al. Intraoperative assessment of sentinel lymph nodes in patients with breast carcinoma: accuracy of rapid imprint cytology compared with definitive histologic workup. Cancer. 2002;96:150–6.

Henry-Tillman RS, Korourian S, Rubio IT, Johnson AT, Mancino AT, Massol N, et al. Intraoperative touch preparation for sentinel lymph node biopsy: a 4-year experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:333–9.

Aihara T, Munakata S, Morino H, Takatsuka Y. Comparison of frozen section and touch imprint cytology for evaluation of sentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:747–50.

Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, Fleige B, Hausschild M, Helms G, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:609–18.

Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, Ahrendt GM, Wilke LG, Taback B, et al. Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology: sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1455–61.

Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Blumencranz PW, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305:569–75.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sae Ishihara and Tamami Morisaki (Department of Surgical Oncology, Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine) for helpful advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SHK participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. NO helped with data collection and manuscript preparation. YA, KK, SN, HK, and TT helped with study data collection and participated in its design. MO helped with data collection and manuscript preparation. SK and KH conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

SHK, SN, HK, and TT are MD, PhD, Assistant Professors. NO is an MD, PhD, Associate Professor. YA and KK are MD, graduate students. MO, SK, and KH are MD, PhD, Professors.

Naoyoshi Onoda, Yuka Asano, Kento Kurata, Satoru Noda, Hidemi Kawajiri, Tsutomu Takashima, Masahiko Ohsawa, Seiichi Kitagawa and Kosei Hirakawa contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kashiwagi, S., Onoda, N., Asano, Y. et al. Ambulatory sentinel lymph node biopsy preceding neoadjuvant therapy in patients with operable breast cancer: a preliminary study. World J Surg Onc 13, 53 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0471-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0471-3