Abstract

Background

A person’s chronic health condition or disability can have a huge impact on the quality of life (QoL) of the whole family, but this important impact is often ignored. This literature review aims to understand the impact of patients' disease on family members across all medical specialities, and appraise existing generic and disease-specific family quality of life (QoL) measures.

Methods

The databases Medline, EMBASE, CINHAL, ASSIA, PsycINFO and Scopus were searched for original articles in English measuring the impact of health conditions on patients' family members/partner using a valid instrument.

Results

Of 114 articles screened, 86 met the inclusion criteria. They explored the impact of a relative's disease on 14,661 family members, mostly 'parents' or 'mothers', using 50 different instruments across 18 specialities including neurology, oncology and dermatology, in 33 countries including the USA, China and Australia. These studies revealed a huge impact of patients' illness on family members. An appraisal of family QoL instruments identified 48 instruments, 42 disease/speciality specific and six generic measures. Five of the six generics are aimed at carers of children, people with disability or restricted to chronic disease. The only generic instrument that measures the impact of any condition on family members across all specialities is the Family Reported Outcome Measure (FROM-16). Although most instruments demonstrated good reliability and validity, only 11 reported responsiveness and only one reported the minimal clinically important difference.

Conclusions

Family members' QoL is greatly impacted by a relative's condition. To support family members, there is a need for a generic tool that offers flexibility and brevity for use in clinical settings across all areas of medicine. FROM-16 could be the tool of choice, provided its robustness is demonstrated with further validation of its psychometric properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A person’s chronic health condition or disability can have a huge impact on the quality of life (QoL) of the whole family. Sometimes this impact may be similar to or even greater than that experienced by the patient [1,2,3]. Although awareness of the impact of a person’s disease on family quality of life (FQoL) has recently been increasing, there is a need to measure this impact in the clinical setting to inform those providing support to the family. Turnbull et al. first proposed the term in 2000 and defined normal “family quality of life” as being "where the family's needs are met, and family members enjoy their life together as a family and have the chance to do things which are important to them" [4].

Golics et al.’s [5] detailed literature review of the impact of chronic disease on a patient's family revealed that various aspects of family life are affected by relative’s health condition. That review only identified information about a few disease areas and specialities [5] and concluded that there was no generic instrument at that time to measure disease impact on family members of patients.

The investigation of FQoL is a newly emerging field, with research now extending to many different areas of medicine. It is, therefore, timely to update the existing knowledge base on the family impact of disease and identify the development of new generic and disease-specific FQoL tools. This critical appraisal of the literature builds on the areas covered by Golics et al. [5] and summarises the greatly increased research activity over the last seven years. It aims to identify the impact of chronic disease on family members of patients across a range of medical specialities and appraise the characteristics and measurement properties of existing generic and disease-specific FQoL measures.

The definition of ‘family’ has changed over time and its use is no longer restricted to describing 'two parents and their children living under the same roof’. In this review, we use the term as defined by Poston et al. [6] as “People who think of themselves as part of the family, whether related by blood or marriage or not and who support and care for each other on a regular basis”. This review studies the impact of a patient's disease on all family members, including partners, whether or not they are also carers. Although the terms family caregivers, carers and informal caregivers are often used interchangeably, the only caregivers covered by this review are those unpaid carers (caregivers) who are family members or partners.

Methods

Search strategy

A search strategy was developed to identify studies published up to January 2020 that reported the impact of chronic disease on patients’ family members and partners. Six electronic databases were searched: Medline via OVIDSP; EMBASE via OVIDSP; CINHAL via EBSCO; ASSIA via ProQuest; PsycINFO Via OVIDSP; and Scopus using the PICO framework (Population: family members of chronic patients, Intervention: Patients chronic illness, Comparison: Non-applicable, Outcome: impact on family members) to identify and record the data (Additional file 1: Table S1a and S1b). The PICO framework was developed by the lead author and agreed by the other authors. The reference lists of included articles were also examined to ensure that all relevant articles were captured.

The search to identify existing generic and disease-specific FQoL measures was extended by combining search terms such as ‘family*or caregiver’ and ‘quality of life’ with the terms scale, index, measure, instrument, assessment, surveys, questionnaires, inventory, tools, generic or disease-specific (Additional file 1: Table S2). In addition, hand searches were carried out of the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) [7] database and the reference lists of relevant articles. Google Scholar was searched for articles reporting development or psychometric properties of the instruments identified.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included in the review if the source was an original paper, in the English language and measuring the impact of chronic illness or disability on patients' family members/partner using a valid tool. Studies were excluded if they were book chapters, congress abstracts, if they used qualitative methodology or if the caregiver was not a family member. This review paper is in two parts, the first part focuses on the impact of a patient’s disease on family members and the second part appraises the instruments available to measure this impact. As one of the inclusion criteria for the second part was only to include quantitative techniques, it was felt methodologically appropriate to align the two parts by including only quantitative studies in the first part. We recognize this could be considered as a limitation of the study.

Screening

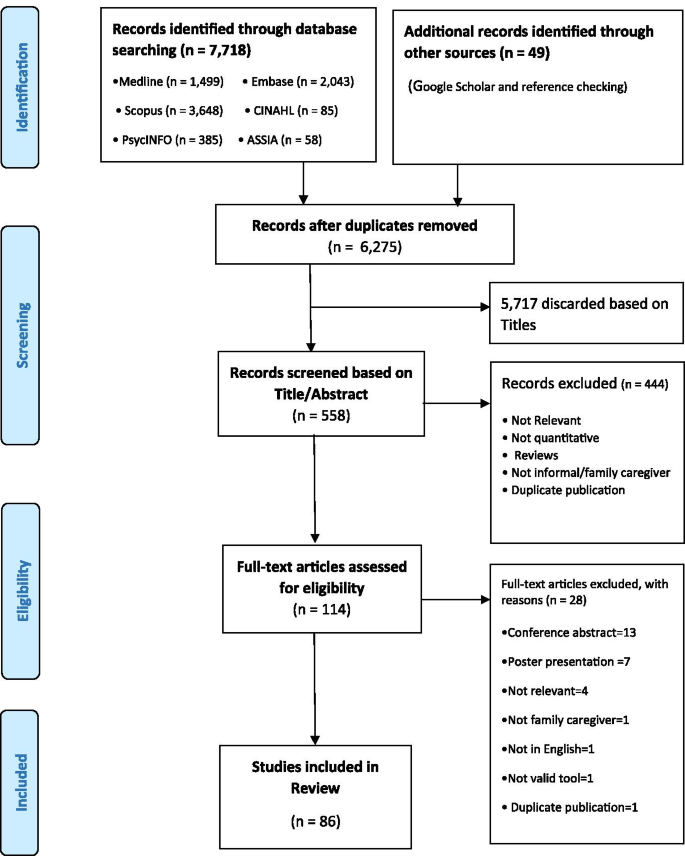

In the first stage of article screening, duplicates were removed, and irrelevant titles and abstracts were discarded based on eligibility criteria. In the second stage, full-text articles of potentially relevant abstracts were read and assessed against eligibility criteria by RS to make a final decision about study selection agreed by MSS and AYF.

Data extraction

Data extraction was carried out by RS and was discussed using an iterative process with other members of the research team (MSS and AYF). The data extracted included authors, publication year, country of study, study design, sample size, patients’ chronic disease, family member gender, relationship to the patient, impact on the family members and tools used to measure this impact (Additional file 1: Table S3).

A separate data extraction table was used for recording psychometric properties of identified family QoL instruments.

Synthesis of data

We used a thematic approach to synthesise findings. Selected papers were carefully read by RS: in case of ambiguity, papers were discussed with FMA, AYF and MSS to ensure accuracy of data extraction. The data on the impact of patients’ disease on family members were summarised as short notes for the 86 studies. These notes were then coded to capture their essence and finally, codes were sorted into potential themes.

Quality assessment and risk of bias

The quality of selected papers and assessment of risk of bias was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs quality assessment tool for cross-sectional and cohort studies, with the involvement of MSS and AYF [8]. The checklist consists of 8–11 questions with answers “yes”, “no” and “unclear”. When all answers were “yes”, the study was considered to have less chance of bias and if any answer was “no”’ the study was classified as having a risk of bias. The PRISMA principles were followed to ensure robustness of the review as well as minimising bias [9].

Results

Screening

A total of 7,767 articles were identified. After removing duplicates and irrelevant titles, 558 abstracts were screened. The resultant 114 articles underwent full-text review, 86 articles met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

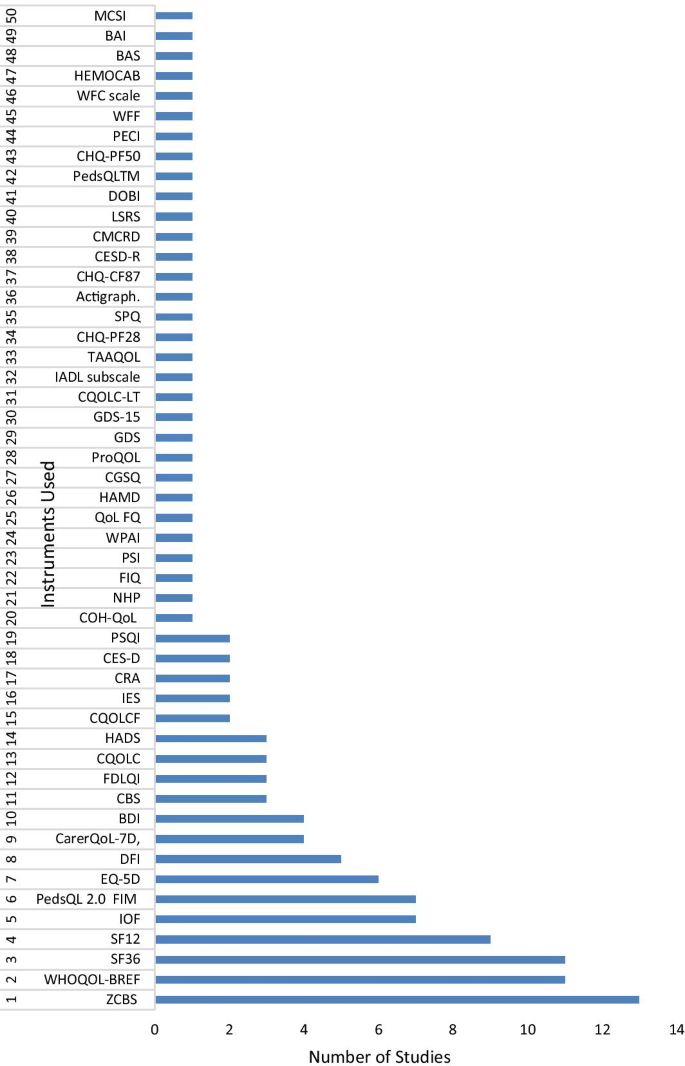

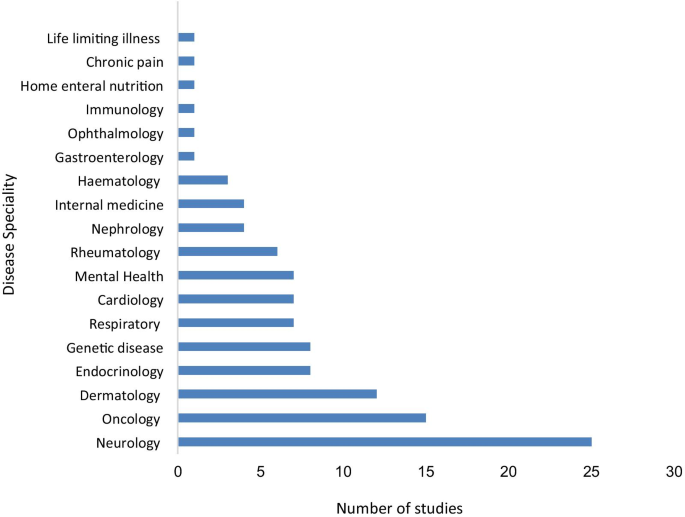

Eighty-one studies were cross-sectional, and five studies were longitudinal prospective cohort studies with follow-up ranging from one month to two years. The studies explored the impact of a relative's disease on a total of 14,661 family members, mostly 'parents' or 'mothers', using 50 different tools across 18 specialities including neurology, oncology and dermatology and covering 33 countries including the USA, China, and Australia (Figs. 2 and 3; Additional file 1: Table S4 and S5). The most widely used tool to measure the impact of a patient's disease on a family member was the Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale (13 studies) followed by WHOQOL (11), SF-36 (11), SF-12 (nine), IOF (seven) and EQ-5D (six) (Fig. 2). While most of the articles reported the impact of a single chronic disease on family members, ten studies included more than one chronic condition, allowing comparison of the family impact of different diseases.

Instruments used in the reviewed studies to measure the impact of the disease on family members/partners. ZCBS: Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale; WHOQOL: The World Health Organization Quality of Life; SF36: The Short Form (36) Health Survey; SF12: 12-item Short Form Health Survey; IOF: Impact on Family Scale; EQ-5D: Euroqol- 5 Dimension; PedsQL 2.0 FIM: PedsQL TM 2.0 Family Impact Module; DFI: Dermatitis Family Impact questionnaire; CBS: Caregiver Burden Scale; CarerQoL-7D: Care-related Quality of Life instrument-7 Dimension; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; FDLQI: Family Dermatology Life Quality Index; CQOLC: Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; CQOLCF: Caregiver Quality of Life Cystic Fibrosis; IES: The Impact of Event Scale; CRA: The Caregivers Reaction Assessment Scale; CES-D: Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; COH-QOL: City of Hope Quality of life Questionnaire: NHP: The Nottingham Health profile questionnaire; FIQ: Family Impact Questionnaire; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSI: The Parenting Stress Index Questionnaire; WPAI-SHP: The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment-Specific Health Problem V2.0; QoLFQ: QoL Family Questionnaire; HAMD: Hamilton Depression Scale; CGSQ: the Caregiver Strain Questionnaire. ProQOL: Professional Quality of Life; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; GDS-15: Geriatric Depression Scale-15; CQOLC-LT: Caregiver Quality of life index-Liver Transplantation; IADL subscale: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; TAAQOL: TNO-AZL Questionnaire for Adult Health-Related Quality of life; CHQ-PF28: Child Health Questionnaire-Parent Form-28; SPQ: Sibling Perception Questionnaire; CHQ-CF87: Child Health Questionnaire-Child Form 87; CESD-R: Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (revised); CMCRD: Caring for my Child with a Juvenile Rheumatic Disease; LSRS: Lifespan Sibling Relationship scale; DOBI: Dutch Objective Burden Inventory; CHQ-PF50: Child Health Questionnaire-Parent Form 50; PECI: Parent Experience of Child Illness; WFF: Work-Family Facilitation scale; WFC scale: Work-Family Conflict scale; PedsQLTM: Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory TM; HEMOCAB: Hemophilia Associated Caregiver Burden Scale; BAS: Burden assessment Scale; BAI: Becks Anxiety Inventory; MCSI: Modified version of Caregiver Strain Index

Quality assessment and risk of bias

Thirteen cross-sectional studies and one cohort study did not mention confounders and strategies to address them while one cohort study did not mention reasons for loss of follow-ups. However, the remaining requirements were met for all of these studies, which all fulfilled the minimum criteria for quality. None of the 86 studies was rejected based on their quality or risk of bias. Overall, all studies were moderate to high quality (Additional file 1: Table S6).

Synthesis of findings—key impact areas

This review revealed a huge impact of patients’ illness on family members’ QoL [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. In general, relatives’ chronic diseases impacted family members in similar ways, with some conditions such as cancer having a bigger impact than others. Some common themes identified in this review are discussed below.

Emotional and psychological impact

Caring for a relative’s chronic disease affects family members’ lives in many ways, impacting their emotional and psychological wellbeing [19]. The family members caring for their relative with a chronic disease were at risk of themselves developing a mental health condition, with an adult offspring or spouse at higher risk than other family members [10, 20, 21], and suffered similar psychological distress, depression and anxiety levels to that of the patient [22,23,24]. The presence of anxiety and/or depression in the family member was the most consistent factor influencing family members’ burden and perceived health-related QoL (HRQoL) [25, 26].

Nature of relationship and psychological impact

Mothers of children with chronic disease experienced high rates of stress, anxiety and depression [15, 27,28,29,30]. Parenting stress was higher when a child was of pre-school age [31, 32] and displaying disruptive behaviours and developmental disabilities [33] or showing flares due to increased severity of their condition [34, 35]. Some parents perceived the increased caring demands of a sick child as 'intrusive' which led to higher levels of parental stress and psychological distress [36] affecting the perception of burden experienced by the mother [37]. However, this emotional distress did not result in mothers being less caring of the sick child [38]. The children of mothers with a chronic condition experienced more symptoms of hyperactivity and inattention, especially when the mothers had psychological problems [39]. Siblings of children with a more severe chronic condition and an unpredictable prognosis reported more internalising of problems and behavioural difficulties than siblings of children with a chronic condition that followed a daily routine treatment pattern [40]. However, poor emotional health of siblings of children with controlled asthma was not related to disease severity [41]. Moreover, what is worrying is that parents are sometimes unaware of the impact of their child’s disease on their other children [42].

Gender differences

Female family members, spouses and mothers, experienced significantly higher rates of depression and anxiety than male family members [15, 21, 25, 28, 29, 43] and the impact was greater when patients suffered from a severe disease such as a long-term mental health condition [44]. However, two studies showed fathers experiencing more stress [45] and lower HRQoL [46] than mothers. Such paternal outcomes could be explained based on increased stressors arising from disease flares, such as additional medical visits and medical bills, both of which could be particularly distressing for fathers compared to mothers [46]. The reverse gender difference was found in siblings of a patient, with female siblings experiencing a lower QoL than male siblings [40].

Impact on physical health

Caring for a relative with a chronic disease can have an impact on family members’ physical health owing to the burden resulting from the relative’s functional disabilities, cognitive impairment [27, 47, 48], medication management [49] duration of care [43, 50] and total daily hours spent on assisting patients with basic activities of daily living and medical tasks [12, 50,51,52]. Caring for their relative can leave family members overwhelmed and physically exhausted [53, 54], which may result in compassion fatigue. It is not the total number of years of caregiving that contributed to differences in compassion fatigue, but the number of hours per week [55], suggesting that intensity of caring rather than duration is the critical factor. Furthermore, family members of people with less severe chronic diseases reported only a moderate burden on QoL [56, 57], indicating that caregiving burden is related to the severity of the patient's disease and the family member's perception of burden [35, 58].

Sleep

The physical health of family members caring for their relative was impacted by poor sleep quality [59,60,61,62,63,64]. Meltzer et al. [61] found that parents of ventilator-assisted children experienced shorter sleep duration and greater variability in sleep quality impacting their physical health compared to parents of healthy children. In the mothers of children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, impaired sleep quality was related to the disease duration [62], while the sleep disturbance in the parents of children with atopic disease was related to the children’s sleep disruption [63]. The partners of cancer patients experienced poor sleep quality: there was a significant correlation between patients' and their partners' sleep quality and sleep onset latency [60]. Although partners used medication to minimise the negative impact of sleep problems, Chen et al. [60] argue that this could have affected their ability to respond to the needs of the patient, indicating that many family members may be hesitant to use drugs to aid sleep.

Impact on social, leisure and daily activities

Family members caring for a relative with a chronic condition experience a considerable impact on their social, leisure and daily activities [38, 51, 58, 65, 66], with women reporting greater disruption than men [67]. Most family members caring for their relative reported difficulties in combining caring tasks with daily activities [29, 68, 69].

Parents of children with chronic disease reported less opportunity for leisure and social activities [38, 53, 68, 70]. The high caregiving demands of children with developmental disabilities, especially if outwardly visible, contributed to social isolation [33]. The parents of children with obsessive compulsive disorder experienced interruptions in social life such as postponing social activities [71]. Parents of children receiving palliative care felt little desire to go out, indicating that the severity of their child's disease led to a loss of interest in leisure activities [72].

There seems to be a cultural aspect to the impact of caregiving on social life. Japanese caregivers reported high social scores on the Zarit burden scale [73], even when their perception of general health was lower than that of the care recipient. This indicates that unlike Western caregivers, Japanese caregivers do not report their feelings about their social life being impacted by caregiving [73]. Arab mothers of children with disabilities experienced reduced social interactions and lower QoL due to the cultural beliefs and the stigma attached to having a child with a disability [48].

Impact on family relationships

A relative's chronic condition has an impact on the relationships among family members and between the patient and the family members [29, 74, 75]. Caring for a family member not only impacts the carer but also the whole family [16, 76] and better family relationships improved QoL for both patient and family members [35, 69, 77].

Mothers caring for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional developmental disorder (ODD) experienced negative feelings towards their affected child. Some mothers attributed their child’s ODD to increased conflicts between them and their partners [74]. However, having more children was seen as being protective against partner conflict and maternal hostility, as siblings could assist the mother by caring for the sick child, thereby reducing parental stress and negative feelings towards the child [74]. Conversely, siblings may internalise their emotional reactions to the situation, leading to behavioural problems [40]. Better alignment and coordination between parents and involving the siblings, however, could lead to family cohesion, tackling the problem together.

Partners of patients experienced poor sexual life and relationship quality because of the patient's symptoms [68, 78], with a significant decrease in the partners’ ability to spend quality time with the patient [70], leading to marital conflicts [68]. For many, the caregiving role restricted them from having more children [72]. Knap et al. [72] reported that 48% of parents of children with life-limiting illnesses choose not to have more children because of their child's illness and associated caring responsibilities.

Financial impact

Caring for a relative with a chronic disease can necessitate increased expenditure [15, 31, 67, 68, 79,80,81,82,83]. In an Australian study, the annual personal cost for mild, moderate, and severe atopic dermatitis was calculated at Aus$330, 818, and 1255, respectively, with most being spent on medication, dressings and non-irritant clothing [64]. In a Swedish study, 20% of parents reported experiencing financial difficulties even after the cost of the chronic disease treatment was covered by the welfare system [84]. The family members reduced their working hours or left their jobs to take up their caring responsibilities. This and the expense of hospital visits contributed to their financial difficulties [64, 84, 85].

Impact on work

Work was seen to have a positive impact on the QoL of mothers, as it provided temporary relief from their caring role, time to socialise and offset the financial burden [47, 71]. However, many family members caring for their relative suffered work impairment [75, 86] and had to give up their jobs, change jobs, alter career choices or reduce their work hours to look after an ill family member and to manage hospital visits [64, 70, 87, 88].

Positive aspect of caregiving

Despite the physical, social and psychological impact that a relative having a disease has on family members, many family members reported a positive experience of caregiving, with older family members reporting more satisfaction than younger ones [55]. Meriggi et al. [67] reported 93.5% family members caring for their relative were happy with their role. Son et al. [77] attribute positivity in family members caring for cancer patients to their spiritual upliftment. Awadalla et al. [89] attribute this positive impact to family cohesion, and an attitude of hopefulness. Adult siblings caring for their parents reported that they see caregiving as a way of giving something back to parents [90]. Although the health status of family members with caring experience was lower than that of non-carers in an Australian study, the difference in scores did not reach the minimal important difference (MID) magnitude for either the mental or physical domains of SF-12, suggesting that caregivers might be satisfied in their caring roles [91].

Existing family QoL instruments

The appraisal of the family QoL measures identified 48 instruments measuring the impact of a patient's disease on family members. Forty-two of the instruments are disease or speciality specific and are limited to that particular group of patients. The properties of these measures are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

The review also identified Six population-specific/generic measures: their properties are summarised in Tables 3 and 4. Five of these measures (Impact on Family Scale, the Beach Centre Family Quality of Life, the PedsQL™ Family Impact Module, Family Quality of Life Survey and Care-related QoL), are aimed at specific populations of carers (parents of children, family members of people with disability, informal caregivers not necessarily family members of people with long term conditions). The only generic instrument that measures the impact of any condition on family members across all specialities is the FROM-16.

The HRQoL instruments, regardless of having been developed for patients or their family member/partner, should demonstrate essential psychometric properties such as validity, reliability and responsiveness to change [159, 160]. Although most instruments demonstrated good internal consistency, reliability and construct validity, only 11 reported responsiveness and only one reported the MID. Thus, it is not known whether these instruments are sensitive to detecting change over time in family members' QoL.

Discussion

This review has demonstrated that family members caring for relatives with various chronic diseases are impacted in similar ways in terms of physical, social and psychological wellbeing. The high number of FQoL instruments identified in this review demonstrates a growing interest in FQoL, though most research has focused on a few medical fields including neurology, oncology and dermatology, findings consistent with the previous review [5]. One key strength of this current review is that its findings are based on studies that have used valid tools to measure the impact of a patient's chronic disease on a family member/partner. The studies included have used many different instruments to measure the impact of chronic disease on family members, indicating a lack of consensus on the use of instruments: perhaps a clear consensus has not yet emerged because this field is still young. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of the instruments used prevents comparison of the impact of caregiving on family members across disease areas. Such comparison is important in identifying the most vulnerable family members and directing them to appropriate support. This is critical as a physically unhealthy family member would be less able to discharge their caregiving duties, thus having a negative impact on the patients' health [20]. While many studies in this review have used disease-specific instruments, most used generic health status or population instruments to measure the family impact of a person's chronic condition, indicating a strong need for a generic QoL measure specific to family members. Furthermore, most instruments used in this review have been designed keeping patients in mind and may not address issues relevant to family members. Using a measure designed to be family-specific should provide a better understanding of the needs of family members, including support services. Disease-specific FQoL instruments are used to assess QoL of family members of people with a specific disease and thus can detect changes in family member’s QoL following clinical interventions. Generic FQoL instruments on the other hand, can assess the effects of a wide range of diseases or treatment on the QoL of a partner or family member. Published research has shown that family members caring for relatives with different health conditions are impacted in similar ways [161]. Thus, generic FQoL instruments allow the comparison of QoL of individuals across different disease areas and identification of population-wide trends. While disease-specific instruments can help clinicians to understand the extent to which a partner or family member has been affected by a person’s disease and inform appropriate treatment decisions, they cannot be used to compare across conditions or between treatments. Moreover, generic instruments can measure the family impact of disease in areas where there are no disease-specific measures. Some research studies may use both generic and disease-specific instruments to capture the different patient/family member viewpoints or to validate the results of using each type of instrument. The FROM-16 could fill this gap as a generic family outcome measure since it has been developed directly from the experience of family members, for family members. One practical feature of FROM-16 is that it is a user-friendly and relatively simple questionnaire with an average completion time of 2–3 min, making it a practical tool for use in a clinical setting.

There are some limitations of this review. The review is not a systematic review. Although not a systematic review, it followed rigorous methodology and fulfilled 19 relevant PRISMA checklist items (Additional file 2: Table S1) [8]. Besides, the review only included studies in the English language, thus limiting understanding of the impact of patients' disease on family members in different cultures. Nevertheless, most studies carried out in different cultures are usually published in English language scientific journals; this suggests the amount of missed information may be minimal. Most studies in this review were cross-sectional. Only five studies were longitudinal, revealing that greater carer burden was associated with poor physical and mental health and lower QoL of family members over time, with women being impacted more than men. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to build understanding of the long-term family impact of disease. This is important as most acute and chronic diseases may influence major life-changing decisions, thus understanding long-term impacts may help clinicians in developing better management plans for patients and their family members [162]. In addition, the majority of family members caring for relatives in the studies reviewed were women, mostly mothers. There is a dearth of research on the impact of caregiving on fathers, although this review highlighted two studies where fathers were impacted more than mothers. The fact that fathers are mostly unavailable at the point of contact results in the impact on fathers being forgotten or difficult to obtain. Thus, future research should focus on the impact of children's diseases on fathers.

An appraisal of existing FQoL instruments identified a recent plethora of FQoL measures indicating the growing recognition of the importance of FQoL. Only a few instruments have published responsiveness and MID information, however evidence of responsiveness is essential for such questionnaires to be useful for clinical monitoring or as an outcome measure to assess the value of interventions. Information concerning MID is important for the clinician to be able to interpret change in scores over time. Most instruments reviewed were developed recently, and perhaps new studies underway might later report their further psychometric properties. Further psychometric testing of existing measures is required. Furthermore, all instruments identified in this review were created in developed countries, highlighting a need for cross-cultural validation in developing countries [163].

Conclusions

In conclusion, this review found that family members caring for their sick relative experience a huge but similar impact on their physical, social and psychological wellbeing across different disease areas. However, to translate this evidence into practice and support family members impacted by their relative's disease, there is a need for a generic family QoL measure which offers acceptable practicality and flexibility both to the relatives and to researchers as well as to clinicians. This review has identified FROM-16 as the only generic user-friendly instrument that can be implemented across all disease areas to measure the family impact of a person with a disease. However, to support the use of FROM-16 across all disciplines of medicine, there is a need for further examination of its psychometric properties. Furthermore, with greater digitalisation of healthcare, such information could be captured routinely and combined with that of the patient’s which would, no doubt, enhance the appropriateness of treatment decision-making. There are many reasons why the routine capture of quality of life information concerning patients may be helpful in enhancing the quality of clinical care [164]. Exactly similar potential advantages may be gained by the use of family quality of life measures. The final thought in this context is the utility of such instruments in meeting the aftermath challenges of the current pandemic crisis and impact of Long Covid on families of the survivors.

Availability of data and materials

All data are included within the article and supplemental material.

Change history

31 August 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01839-0

Abbreviations

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- FQOL:

-

Family quality of life

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- ODD:

-

Oppositional developmental disorder

- FROM-16:

-

Family reported outcome measure-16

- MID:

-

Minimal important difference

- NF:

-

Not Found

References

Rees J, O’Boyle C, MacDonagh R. Quality of life: impact of chronic illness on the partner. J R Soc Med. 2001;94(11):563–6.

Weitzenkamp DA, Gerhart KA, Charlifue SW, Whiteneck GG, Savic G. Spouses of spinal cord injury survivors: the added impact of caregiving. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(8):822–7.

Basra M, Finlay AY. The family impact of skin diseases: the Greater Patient concept. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(5):929–37.

Turnbull AP, Turnbull HR, Poston D, Beegle G, Blue-Banning M, Diehl K, Frankland C, Lord L, Marquis J, Park J, Matt S. Enhancing quality of life of families of children and youth with disabilities in the United States. 2000.

Golics CJ, Basra MKA, Finlay AY, Salek S. The impact of disease on family members: a critical aspect of medical care. J R Soc Med. 2013;106(10):399–407.

Poston D, Turnbull A, Park J, Mannan H, Marquis J, Wang M. Family quality of life: a qualitative inquiry. Ment Retard. 2003;41(5):313–28.

COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments COSMIN. Database of systematic reviews of outcome measurement instruments 2021 [online] 2021. https://database.cosmin.nl/?utf8=%E2%9C%93&search_field=all_fields&q=family+caregivers.

Moola SMZ, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Lisy K, Mu P-F. The Joanna Briggs Institute. . Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. 2017. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Arora A, Gupta ID, Sharma P, Dudani K. A comparative study of family burden and quality of life of caregivers of patients with chronic psychiatric versus chronic medical disorders. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;1:S32–S3.

Jirakova A, Vojackova N, Gopfertova D, Hercogova J. A comparative study of the impairment of quality of life in Czech children with atopic dermatitis of different age groups and their families. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(6):688–92.

Karg N, Graessel E, Randzio O, Pendergrass A. Dementia as a predictor of care-related quality of life in informal caregivers: a cross-sectional study to investigate differences in health-related outcomes between dementia and non-dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):189.

Lazow MA, Jaser SS, Cobry EC, Garganta MD, Simmons JH. Stress, depression, and quality of life among caregivers of children with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33(4):437–45.

Mazzone L, Postorino V, De Peppo L, Della Corte C, Lofino G, Vassena L, et al. Paediatric non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease: impact on patients and mothers' quality of life. Hepat Mon. 2013;13(3):e7871.

Pustišek N, Vurnek Živkovic M, Šitum M. Quality of life in families with children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(1):28–32.

Tadros A, Vergou T, Stratigos AJ, Tzavara C, Hletsos M, Katsambas A, et al. Psoriasis: is it the tip of the iceberg for the quality of life of patients and their families? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(11):1282–7.

Wei L, Li J, Cao Y, Xu J, Qin W, Lu H. Quality of life and care burden in primary caregivers of liver transplantation recipients in China. Medicine. 2018;97(24).

Macchi ZA, Koljack CE, Miyasaki JM, Katz M, Galifianakis N, Prizer LP, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease: a palliative care approach. Ann Palliat Med. 2019:S24–S33.

Bruce DG, Paley GA, Nichols P, Roberts D, Underwood PJ, Schaper F. Physical disability contributes to caregiver stress in dementia caregivers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(3):345–9.

Sewitch MJ, McCusker J, Dendukuri N, Yaffe MJ. Depression in frail elders: impact on family caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(7):655–65.

McCusker J, Latimer E, Cole M, Ciampi A, Sewitch M. Major depression among medically ill elders contributes to sustained poor mental health in their informal caregivers. Age Ageing. 2007;36(4):400–6.

Walsh JD, Blanchard EB, Kremer JM, Blanchard CG. The psychosocial effects of rheumatoid arthritis on the patient and the well partner. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37(3):259–71.

Yildirim SA, Ozer S, Yilmaz O, Duger T, Kilinc M. Depression, anxiety and health related quality of life in the caregivers of the persons with chronic neurological illness. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2009;29(6):1535–42.

Rioux JP, Narayanan R, Chan CT. Caregiver burden among nocturnal home hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2012;16(2):214–9.

Carod-Artal FJ, Ferreira Coral L, Trizotto DS, Menezes MC. Burden and perceived health status among caregivers of stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28(5):472–80.

Ito E, Tadaka E. Quality of life among the family caregivers of patients with terminal cancer at home in Japan. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2017;14(4):341–52.

Okurowska-Zawada B, Wojtkowski J, Kułak W. Quality of life of mothers of children with myelomeningocele. Pediatr Pol. 2013;88(3):241–6.

Serin HM, Akinci A, Mermi O, Atmaca M, Yilmaz E. The depression and anxiety profiles of motherswho have children with epilepsy. Turk Klinikleri Pediatr. 2016;25(3):133–8.

Ten Hoopen LW, de Nijs PFA, Duvekot J, Greaves-Lord K, Hillegers MHJ, Brouwer WBF, et al. Children with an autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers: capturing health-related and care-related quality of life. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(1):263–77.

Sharghi A, Karbakhsh M, Nabaei B, Meysamie A, Farrokhi A. Depression in mothers of children with thalassemia or blood malignancies: a study from Iran. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2.

Chernyshov PV, Ho RC, Monti F, Jirakova A, Velitchko SS, Hercogova J, et al. An international multi-center study on self-assessed and family quality of life in children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23(4):247–53.

Van Nimwegen KJM, Kievit W, van der Wilt GJ, Schieving JH, Willemsen MAAP, Donders ART, et al. Parental quality of life in complex paediatric neurologic disorders of unknown aetiology. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20(5):723–31.

Gupta VB. Comparison of parenting stress in different developmental disabilities. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2007;19(4):417–25.

Grant M, Del Ferraro C, Williams AC, Sun V, Fujinami R, Ferrell B. Quality of life, preparedness, and perceived burden of family caregivers in lung cancer. Support Care in Cancer. 2012;1:S71.

Sikorová L, Bužgová R. Associations between the quality of life of children with chronic diseases, their parents’ quality of life and family coping strategies. Cent Eur J Nurs Midwifery. 2016;7(4):534–41.

Gamwell KL, Mullins AJ, Tackett AP, Suorsa KI, Mullins LL, Chaney JM. Caregiver demand and distress in parents of youth with juvenile rheumatic diseases: examining illness intrusiveness and parenting stress as mediators. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2016;28(6):889–904.

Calderón C, Gómez-López L, Martínez-Costa C, Borraz S, Moreno-Villares JM, Pedrón-Giner C. Feeling of burden, psychological distress, and anxiety among primary caregivers of children with home enteral nutrition. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(2):188–95.

Ho RCM, Giam YC, Ng TP, Mak A, Goh D, Zhang MWB, et al. The influence of childhood atopic dermatitis on health of mothers, and its impact on Asian families. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(3):501–7.

Guo VY, Wong CK, Wong RS, Yu EY, Ip P, Lam CL. Spillover effects of maternal chronic disease on children’s quality of life and behaviors among low-income families. The Patient. 2018;11(6):625–35.

Havermans T, Croock ID, Vercruysse T, Goethals E, Diest IV. Belgian siblings of children with a chronic illness: is their quality of life different from their peers? J Child Health Care. 2015;19(2):154–66.

Yilmaz O, Turkeli A, Karaca O, Yuksel H. Does having an asthmatic sibling affect the quality of life in children? Turk J Pediatr. 2017;59(3):274–80.

Dinleyici M, Carman KB, Ozdemir C, Harmanci K, Eren M, Kirel B, et al. Quality-of-life evaluation of healthy siblings of children with chronic illness. Balkan Med J. 2019;37(1):34–42.

Forbes A, While A, Mathes L. Informal carer activities, carer burden and health status in multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(6):563–75.

Johansson A, Ewertzon M, Andershed B, Anderzen-Carlsson A, Nasic S, Ahlin A. Health-related quality of life—from the perspective of mothers and fathers of adult children suffering from long-term mental disorders. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(3):180–5.

Bonner MJ, Hardy KK, Willard VW, Hutchinson KC. Brief report: psychosocial functioning of fathers as primary caregivers of pediatric oncology patients. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(7):851–6.

Kunz JH, Greenley RN, Howard M. Maternal, paternal, and family health-related quality of life in the context of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(8):1197–204.

Farajzadeh A, Maroufizadeh S, Amini M. Factors associated with quality of life among mothers of children with cerebral palsy. 2020:e12811.

Manee F, Ateya Y, Rassafiani M. A comparison of the quality of life of Arab mothers of children with and without chronic disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2016;36(3):260–71.

Luckett T, Agar M, DiGiacomo M, Lam L, Phillips J. Health status in South Australians caring for people with cancer: a population-based study. Psychooncology. 2019;28(11):2149–56.

Duimering A, Turner J, Chu K, Huang F, Severin D, Ghosh S, et al. Informal caregiver quality of life in a palliative oncology population. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(4):1695–702.

Baji P, Golicki D, Prevolnik-Rupel V, Brouwer WBF, Zrubka Z, Gulacsi L, et al. The burden of informal caregiving in Hungary, Poland and Slovenia: results from national representative surveys. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20(Suppl 1):5–16.

Blanes L, Carmagnani MIS, Ferreira LM. Health-related quality of life of primary caregivers of persons with paraplegia. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(6):399–403.

Arafa MA, Zaher SR, El-Dowaty AA, Moneeb DE. Quality of life among parents of children with heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:91.

Lu L, Pan B, Sun W, Cheng L, Chi T, Wang L. Quality of life and related factors among cancer caregivers in China. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64(5):505–13.

Lynch SH, Shuster G, Lobo ML. The family caregiver experience—examining the positive and negative aspects of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue as caregiving outcomes. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(11):1424–31.

Koşan Z, Yılmaz S, Bilge Yerli E, Köyceğiz E. Evaluation of the burden of care and the quality of life in the parents of turkish children with familial mediterranean fever. J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;48:e21–6.

McDonald L, Turnbull P, Chang L, Crabb DP. Taking the strain? Impact of glaucoma on patients’ informal caregivers. Eye. 2020;34(1):197–204.

Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Veeger N, Tijssen J, Sanderman R, van Veldhuisen DJ. Caregiver burden in partners of Heart Failure patients; limited influence of disease severity. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(6–7):695–701.

Al Robaee AA, Shahzad M. Impairment quality of life in families of children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18(4):243–7.

Chen Q, Terhorst L, Lowery-Allison A, Cheng H, Tsung A, Layshock M, et al. Sleep problems in advanced cancer patients and their caregivers: Who is disturbing whom? J Behav Med. 2019:1–9.

Meltzer LJ, Sanchez-Ortuno MM, Edinger JD, Avis KT. Sleep patterns, sleep instability, and health related quality of life in parents of ventilator-assisted children. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(3):251–8.

Nozoe KT, Polesel DN, Moreira GA, Pires GN, Akamine RT, Tufik S, et al. Sleep quality of mother-caregivers of Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Sleep Breath. 2016;20(1):129–34.

Ridolo E, Caffarelli C, Olivieri E, Montagni M, Incorvaia C, Baiardini I, et al. Quality of sleep in allergic children and their parents. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2015;43(2):180–4.

Su JC, Kemp AS, Varigos GA, Nolan TM. Atopic eczema: Its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76(2):159–62.

Haverman L, van Oers HA, Maurice-Stam H, Kuijpers TW, Grootenhuis MA, van Rossum MA. Health related quality of life and parental perceptions of child vulnerability among parents of a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a web-based survey. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2014;12:34.

Splinter K, Niemi A-K, Cox R, Platt J, Shah M, Enns GM, et al. Impaired health-related quality of life in children and families affected by methylmalonic acidemia. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(5):936–44.

Meriggi F, Andreis F, Premi V, Liborio N, Codignola C, Mazzocchi M, et al. Assessing cancer caregivers’ needs for an early targeted psychosocial support project: the experience of the oncology department of the Poliambulanza Foundation. Palliat Supportive Care. 2015;13(4):865–73.

Jafari H, Ebrahimi A, Aghaei A, Khatony A. The relationship between care burden and quality of life in caregivers of hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):321.

O’Mahony J, Marrie RA, Laporte A, Bar-Or A, Yeh EA, Brown A, et al. Pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis is associated with reduced parental health-related quality of life and family functioning. Mult Scler J. 2019;25(12):1661–72.

Suthoff E, Mainz JG, Cox DW, Thorat T, Grossoehme DH, Fridman M, et al. Caregiver burden due to pulmonary exacerbations in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2019;215:164-71.e2.

Suculluoglu Dikici D, Eser E, Cokmus FP, Demet MM. Quality of Life and associated risk factors in caregivers of patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(4):579–86.

Knapp CA, Madden VL, Curtis CM, Sloyer P, Shenkman EA. Family support in pediatric palliative care: How are families impacted by their children's illnesses? J Palliat Med. 2010; 13(4):421–426.

Morimoto T, Schreiner AS, Asano H. Caregiver burden and health-related quality of life among Japanese stroke caregivers. Age Ageing. 2003;32(2):218–23.

Fleck K, Jacob C, Philipsen A, Matthies S, Graf E, Hennighausen K, et al. Child impact on family functioning: a multivariate analysis in multiplex families with children and mothers both affected by attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). ADHD. 2015;7(3):211–23.

Mowforth OD, Davies BM, Kotter MR. Quality of life among informal caregivers of patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy: cross-sectional questionnaire study. Interact J Med Res. 2019;8(4):e12381.

Hunfeld JA, Perquin CW, Duivenvoorden HJ, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Passchier J, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, et al. Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(3):145–53.

Son KY, Lee CH, Park SM, Lee CH, Oh SI, Oh B, et al. The factors associated with the quality of life of the spouse caregivers of patients with cancer: a cross-sectional study. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(2):216–24.

Roy A, Minaya M, Monegro M, Fleming J, Wong RK, Lewis SK, et al. Partner burden in celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;1:S179–S80.

Farzi S, Farzi S, Moladoost A, Ehsani M, Shahriari M, Moieni M. Caring burden and quality of life of family caregivers in patients undergoing hemodialysis: a descriptive-analytic study. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2019;7(2):88–96.

Ab. Ghani A, Norhayati N, Muhamad R, Ismail Z. Atopic eczema in children: disease severity, quality of life and its impact on family. Int Med J (1994). 2012;20.

Khair K, Mackensen Sv. Caregiver burden in haemophilia: results from a single UK centre. J Haemoph Pract. 2017;4(1):40.

Al Qadire M, Aloush S, Alkhalaileh M, Qandeel H, Al-Sabbah A. Burden among parents of children with cancer in Jordan: prevalence and predictors. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(5):396–401.

Włodarek K, Głowaczewska A, Matusiak Ł, Szepietowski JC. Psychosocial burden of Hidradenitis Suppurativa patients’ partners. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(8):1822–7.

Hoven EI, Lannering B, Gustafsson G, Boman KK. Persistent impact of illness on families of adult survivors of childhood central nervous system tumors: a population-based cohort study. Psychooncology. 2013;22(1):160–7.

Aung L, Saw SM, Chan MY, Khaing T, Quah TC, Verkooijen HM. The hidden impact of childhood cancer on the family: a multi-institutional study from Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2012;41(4):170–5.

Chua CKT, Wu JT, Yeewong Y, Qu L, Tan YY, Neo PSH, et al. Caregiving and its resulting effects—the care study to evaluate the effects of caregiving on caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in Singapore. Cancers. 2016;8(11).

Khair K, Von Mackensen S. Caregiver burden of parents of children with haemophilia—results from a single UK centre. Haemophilia. 2016;22(Supplement 4):113.

Shalitin S, Hershtik E, Phillip M, Gavan M-Y, Cinamon RG. Impact of childhood type 1 diabetes on maternal work-family relations. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2018;31(5):569–76.

Awadalla AW, Ohaeri JU, Al-Awadi SA, Tawfiq AM. Diabetes mellitus patients’ family caregivers’ subjective quality of life. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(5):727–36.

Ngangana PC, Davis BL, Burns DP, McGee ZT, Montgomery AJ. Intra-family stressors among adult siblings sharing caregiving for parents. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):3169–81.

Luckett T, Agar M, DiGiacomo M, Ferguson C, Lam L, Phillips J. Health status of people who have provided informal care or support to an adult with chronic disease in the last 5 years: results from a population-based cross-sectional survey in South Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2019;43(4):408–14.

Basra MKA, Sue-Ho R, Finlay AY. The family dermatology life quality index: measuring the secondary impact of skin disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(3):528–38.

Basra MKA, Edmunds O, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Measurement of family impact of skin disease: further validation of the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(7):813–21.

Lawson V, Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, Reid P, Owens RG. The family impact of childhood atopic dermatitis: the Dermatitis Family Impact Questionnaire. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(1):107–13.

Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. An audit of the impact of a consultation with a paediatric dermatology team on quality of life in infants with atopic eczema and their families: further validation of the Infants’ Dermatitis Quality of Life Index and Dermatitis Family Impact score. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(6):1249–55.

McKenna SP, Whalley D, Dewar AL, Erdman RAM, Kohlmann T, Niero M, et al. International development of the Parents’ Index of Quality of Life in Atopic Dermatitis (PIQoL-AD). Qual Life Res. 2005;14(1):231–41.

Meads DM, McKenna SP, Kahler K. The quality of life of parents of children with atopic dermatitis: interpretation of PIQoL-AD scores. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(10):2235.

Kondo-Endo K, Ohashi Y, Nakagawa H, Katsunuma T, Ohya Y, Kamibeppu K, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire measuring quality of life in primary caregivers of children with atopic dermatitis (QPCAD). Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(3):617–25.

Katsunuma T, Tan A, Ohya Y. Short version of a quality-of-life questionnaire in primary caregivers of children with atopic dermatitis (QPCAD): development and validation of QP9. Arerugi=[Allergy]. 2013;62(1):33–46.

Chamlin SL, Cella D, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Mancini AJ, Lai JS, et al. Development of the Childhood Atopic Dermatitis Impact Scale: initial validation of a quality-of-life measure for young children with atopic dermatitis and their families. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(6):1106–11.

Chamlin SL, Lai J-S, Cella D, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Mancini AJ, et al. Childhood atopic dermatitis impact scale: reliability, discriminative and concurrent validity, and responsiveness. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(6):768–72.

Eghlileb AM, Basra MK, Finlay AY. The psoriasis family index: preliminary results of validation of a quality of life instrument for family members of patients with psoriasis. Dermatology. 2009;219(1):63–70.

Basra MKA, Zammit AM, Kamudoni P, Eghlileb AM, Finlay AY, Salek MS. PFI-14©: a Rasch analysis refinement of the psoriasis family index. Dermatology. 2015;231(1):15–23.

Méni C, Bodemer C, Toulon A, Merhand S, Perez-Cullell N, Branchoux S, et al. Atopic dermatitis burden scale: creation of a specific burden questionnaire for families. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(11):1426–32.

Boccara O, Méni C, Léauté-Labreze C, Bodemer C, Voisard JJ, Dufresne H, et al. Haemangioma family burden: creation of a specific questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(1):78–82.

Mrowietz U, Hartmann A, Weißmann W, Zschocke I. FamilyPso—a new questionnaire to assess the impact of psoriasis on partners and family of patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(1):127–34.

Dufresne H, Hadj-Rabia S, Taieb C, Bodemer C. Development and validation of an epidermolysis bullosa family/parental burden score. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(6):1405–10.

Dufresne H, Hadj-Rabia S, Méni C, Sibaud V, Bodemer C, Taïeb C. Family burden in inherited ichthyosis: creation of a specific questionnaire. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8(1):28.

Taieb C, Hadj-Rabia S, Monnet J, Bennani M, Bodemer C, the Filière Maladies Rares en D. Incontinentia pigmenti burden scale: designing a family burden questionnaire. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):271.

Vandagriff JL, Marrero DG, Ingersoll GM, Fineberg NS. Parents of children with diabetes: what are they worried about? Diabetes Educ. 1992;18(4):299–302.

Spezia Faulkner M, Clark FS. Quality of life for parents of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 1998;24(6):721–7.

Cappelleri JC, Gerber RA, Quattrin T, Deutschmann R, Luo X, Arbuckle R, et al. Development and validation of the WEll-being and Satisfaction of CAREgivers of Children with Diabetes Questionnaire (WE-CARE). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6(1):3.

Katz M, Volkening L, Dougher C, Laffel L. Validation of the Diabetes Family Impact Scale: a new measure of diabetes-specific family impact. Diabet Med. 2015;32(9):1227–31.

Berdeaux G, Hervié C, Smajda C, Marquis P, The Rhinitis Survey G. Parental quality of life and recurrent ENT infections in their children: development of a questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(6):501–12.

Cohen BL, Noone S, Muñoz-Furlong A, Sicherer SH. Development of a questionnaire to measure quality of life in families with a child with food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(5):1159–63.

Boling W, Macrina DM, Clancy JP. The Caregiver Quality of Life Cystic Fibrosis (CQOLCF) scale: modification and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life in cystic fibrosis family caregivers. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(8):1119–26.

Coyne KS, Matza LS, Brewster-Jordan J, Thompson C, Bavendam T. The psychometric validation of the OAB family impact measure (OAB-FIM). Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(3):359–69.

Barnard D, Woloski M, Feeny D, McCusker P, Wu J, David M, et al. Development of disease-specific health-related quality-of-life instruments for children with immune thrombocytopenic purpura and their parents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:56–62.

Aubeeluck A, Buchanan H. The Huntington’s Disease quality of life battery for carers: reliability and validity. Clin Genet. 2007;71(5):434–45.

Aubeeluck A, Dorey J, Toomi M, Buchanan H. Huntington’s disease quality of life battery for carers-short form.(HDQoLC–SF). 2009.

Doward LC. The development of the Alzheimer's carers' quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res. 1997:639.

Benito-León J, Rivera-Navarro J, Guerrero A, Heras V, Balseiro J, Lorenzo E, et al. The CAREQOL-MS was a useful instrument to measure caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;64:675–86.

Jenkinson C, Dummett S, Kelly L, Peters M, Dawson J, Morley D, et al. The development and validation of a quality of life measure for the carers of people with Parkinson’s disease (the PDQ-Carer). Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(5):483–7.

Morley D, Dummett S, Kelly L, Peters M, Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The PDQ-Carer: development and validation of a summary index score. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;19.

Pillas M, Selai C, Quinn NP, Lees A, Litvan I, Lang A, et al. Development and validation of a carers quality-of-life questionnaire for parkinsonism (PQoL Carers). Qual Life Res. 2016;25(1):81–8.

Migliorini C, Callaway L, Moore S, Simpson GK. Family and TBI: an investigation using the Family Outcome Measure - FOM-40. Brain Inj. 2019;33(3):282–90.

Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Maines ML, Vassar SD, Fitten J, Strickland T. Development and preliminary evaluation of a quality of life measure targeted at dementia caregivers. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7(1):56.

Brown A, Page TE, Daley S, Farina N, Basset T, Livingston G, et al. Measuring the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: development and validation of C-DEMQOL. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(8):2299–310.

Locker D, Jokovic A, Stephens M, Kenny D, Tompson B, Guyatt G. Family impact of child oral and oro-facial conditions. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30(6):438–48.

Cohen R, Leis AM, Kuhl D, Charbonneau C, Ritvo P, Ashbury FD. QOLLTI-F: measuring family carer quality of life. Palliat Med. 2006;20(8):755–67.

Minaya P, Baumstarck K, Berbis J, Goncalves A, Barlesi F, Michel G, et al. The CareGiver Oncology Quality of Life questionnaire (CarGOQoL): development and validation of an instrument to measure the quality of life of the caregivers of patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(6):904–11.

Weitzner MA, Jacobsen PB, Wagner H, Friedland J, Cox C. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) scale: development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1999;8(1):55–63.

Ferrell BR, Ferrell BA, Rhiner M, Grant M. Family factors influencing cancer pain management. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67(Suppl 2):S64–9.

City of Hope National Medical Center. QOL Scale - FAMILY. Copyright: City of Hope National Medical Center. Duarte, CA: City of Hope National Medical Center; 2020. https://prc.coh.org/QOL-Family.pdf.

Boruk M, Lee P, Faynzilbert Y, Rosenfeld RM. Caregiver well-being and child quality of life. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(2):159–68.

Dubé E, De Wals P, Ouakki M. Quality of life of children and their caregivers during an AOM episode: development and use of a telephone questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):75.

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in the parents of children with asthma. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(1):27–34.

Minard JP, Thomas NJ, Olajos-Clow JG, Wasilewski NV, Jenkins B, Taite AK, et al. Assessing the burden of childhood asthma: validation of electronic versions of the Mini Pediatric and Pediatric Asthma Caregiver’s Quality of Life Questionnaires. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(1):63–9.

Chow MY, Morrow A, Heron L, Yin JK, Booy R, Leask J. Quality of life for parents of children with influenza-like illness: development and validation of Care-ILI-QoL. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(3):939–51.

Torres-Made MD, Peláez-Ballestas I, García-Rodríguez F, Villarreal-Treviño AV, Fortuna-Reyna BdJ, de la O-Cavazos ME, et al. Development and validation of the CAREGIVERS questionnaire: multi-assessing the impact of juvenile idiopathic arthritis on caregivers. Pediatric Rheumatol. 2020;18(1):3.

Abreu Paiva LM, Gandolfi L, Pratesi R, Harumi Uenishi R, Puppin Zandonadi R, Nakano EY, et al. Measuring quality of life in parents or caregivers of children and adolescents with celiac disease: development and content validation of the questionnaire. 2019.

Nauser JA, Bakas T, Welch JL. A new instrument to measure quality of life of heart failure family caregivers. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26(1):53–64.

Varni JW, Sherman SA, Burwinkle TM, Dickinson PE, Dixon P. The PedsQL Family Impact Module: preliminary reliability and validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:55.

Stein RE, Jessop DJ. The impact on family scale revisited: further psychometric data. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24(1):9–16.

Williams AR, Piamjariyakul U, Williams PD, Bruggeman SK, Cabanela RL. Validity of the revised Impact on Family (IOF) scale. J Pediatr. 2006;149(2):257–61.

Jalil YF, Villarroel GS, Silva AA, Briceño LS, Ormeño VP, Ibáñez NS, et al. Reliability and validity of the revised impact on family scale (RIOFS) in the hospital context. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2019;3(1):28.

Park J, Hoffman L, Marquis J, Turnbull AP, Poston D, Mannan H, et al. Toward assessing family outcomes of service delivery: validation of a family quality of life survey. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2003;47(Pt 4–5):367–84.

Brouwer WB, van Exel NJ, van Gorp B, Redekop WK. The CarerQol instrument: a new instrument to measure care-related quality of life of informal caregivers for use in economic evaluations. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(6):1005–21.

Isaacs BJ, Brown I, Brown RI, Baum N, Myerscough T, Neikrug S, et al. The international family quality of life project: goals and description of a survey tool. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2007;4(3):177–85.

Perry A, Isaacs B. Validity of the family quality of life survey-2006. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2015;28(6):584–8.

Samuel PS, Tarraf W, Marsack C. Family Quality of Life Survey (FQOLS-2006): evaluation of internal consistency, construct, and criterion validity for socioeconomically disadvantaged families. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2018;38(1):46–63.

Golics CJ, Basra MK, Finlay AY, Salek S. The development and validation of the Family Reported Outcome Measure (FROM-16)© to assess the impact of disease on the partner or family member. Quality life Res. 2014;23(1):317–26.

Scarpelli A, Paiva S, Pordeus I, Varni J, Viegas C, Allison P. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ (PedsQL™) family impact module: reliability and validity of the Brazilian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:35.

Hoffman L, Marquis J, Poston D, Summers J, Turnbull A. Assessing family outcomes: psychometric evaluation of the beach center family quality of life scale. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68.

Waschl N, Xie H, Chen M, Poon KK. Construct, convergent, and discriminant validity of the beach center family quality of life scale for Singapore. Infants Young Child. 2019;32(3):201–14.

Rivard M, Mercier C, Mestari Z, Terroux A, Mello C, Bégin J. Psychometric Properties of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life in French-speaking families with a preschool-aged child diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017;122(5):439–52.

Hoefman RJ, van Exel J, Brouwer WBF. Measuring the impact of caregiving on informal carers: a construct validation study of the CarerQol instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(1):173.

McCaffrey N, Bucholc J, Rand S, Hoefman R, Ugalde A, Muldowney A, et al. Head-to-head comparison of the psychometric properties of 3 carer-related preference-based instruments. Value in Health. 2020.

Guyatt G, Walter S, Norman G. Measuring change over time: assessing the usefulness of evaluative instruments. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(2):171–8.

Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, Wyrwich KW, Norman GR, Aaronson N, et al. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(4):371–83.

Golics CJ, Basra MKA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The impact of patients’ chronic disease on family quality of life: an experience from 26 specialties. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:787–98.

Bhatti Z, Salek M, Finlay A. Chronic diseases influence major life changing decisions: a new domain in quality of life research. J R Soc Med. 2011;104(6):241–50.

Camfield L. Quality of Life in Developing Countries. In: Land KC, Michalos AC, Sirgy MJ, editors. Handbook of social indicators and quality of life research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2012. p. 399–432.

Finlay AY, Salek MS, Abeni D, Tomás-Aragonés L, van Cranenburgh OD, Evers AW, et al. Why quality of life measurement is important in dermatology clinical practice: an expert-based opinion statement by the EADV Task Force on Quality of Life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(3):424–31.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

There was no external funding for this Cardiff University study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS carried out the literature review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AYF, FMA and MSS contributed equally to the extensive revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

RS and FMA declared no competing interest. AYF and MSS are joint copyright holders of FROM-16.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary tables-methods and results.

Additional file 2.

Supplementary table S1-PRISMA Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, R., Ali, F.M., Finlay, A.Y. et al. Family reported outcomes, an unmet need in the management of a patient's disease: appraisal of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes 19, 194 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01819-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01819-4