Abstract

Background

Residential youth care (RYC) institutions aim to provide care and stability for vulnerable adolescents with several previous and present challenges, such as disrupted attachments, wide-ranging adverse childhood experiences, mental health problems, and poor quality of life (QoL). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to provide knowledge of the associations between perceived social support and QoL and to explore the potential moderating effect of perceived social support on QoL for adolescents who have experienced maltreatment and polyvictimization.

Methods

All RYC institutions with adolescents between the ages 12–23 in Norway were asked to participate in the study. A total of 86 institutions housing 601 adolescents accepted the invitation, from which 400 adolescents volunteered to participate. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Interview was used to gather information on maltreatment histories and degree of victimization; the Kinder Lebensqualität Fragebogen was used to measure QoL through several domains (overall QoL, physical well-being, emotional well-being, and self-esteem); and the Social Support Questionnaire was used to measure perceived social support. Linear regression and independent samples t-test were used to study the associations between perceived social support and QoL as well as the potential moderating effect of perceived social support in the association between maltreatment history and QoL.

Results

Perceived social support was positively associated with QoL for both girls and boys, with domain-specific findings. A higher number of different types of support persons was associated with overall QoL, emotional well-being, and self-esteem for boys, but only with self-esteem for girls. Individual social support from RYC staff and friends was associated with higher QoL for girls. However, perceived social support did not moderate the association between maltreatment history and reduced QoL for either sex.

Conclusions

This study emphasizes the importance of maintaining social support networks for adolescents living in RYC, the crucial contribution of RYC staff in facilitating social support, and the potential value of social skills training for these vulnerable adolescents. Furthermore, a wider range of initiatives beyond social support must be carried out to increase QoL among adolescents with major maltreatment and polyvictimization experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adolescents living in residential youth care (RYC) institutions often have a background characterized by adverse childhood experiences (ACE), including abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, making them more prone to negative emotional, behavioral, and social developmental outcomes [1,2,3] as well as lower quality of life (QoL) [4, 5]. Consequently, the professional monitoring and establishment of a positive social climate are important in avoiding negative outcomes [6, 7]. Knowledge of the potential protective factors for vulnerable adolescents' development while living in RYC is generally lacking despite its integral role in providing optimal care and in informing policies and practices for providing high-quality RYC institutions. Perceiving social support can be relevant in this regard; however, adolescents in RYC report lower perceived social support [8] compared to adolescents in the general population. Thus, the aim of the current study is to investigate the associations between perceived social support and QoL for these high-risk adolescents and determine the potential moderating effect of perceived social support on QoL for those with maltreatment and polyvictimization experiences.

Adolescents living in RYC

Adolescents living in RYC are characterized as a vulnerable population, often having experienced neglect and abuse during their childhood [2, 9]. Such a background can potentially lead to poor interpersonal relationships and feelings of instability and distrust, especially when the traumatic event occurs within the family [10, 11]. RYC placements by the Norwegian Child Welfare Services (CWS) are aimed at adolescents who have faced a wide range of challenges or have been raised in troubled backgrounds, making it reasonable to assume that they have experienced neglect to some extent. A Norwegian study among foster children found that 86.3% had experienced serious neglect [12]. Growing up with ACE, several placements, and disrupted attachments have been associated with behavioral, psychological, social, and educational problems among adolescents [13,14,15]. During adolescence, the extensive biological, social, and psychological developments [16] are also influenced by both individual and environmental factors [17]. Even though the primary purpose of RYC placements is to support positive development with the provision of a safe and caring environment, the strain caused by the immediate change in residency can disrupt previously established healthy attachments and ultimately negatively impact the adolescents’ mental health, perceived stress, and social relationships [18, 19]. Consequently, these psychosocial strains put them at greater risk for poor QoL [4, 20], mental health problems [21, 22], and low levels of perceived social support [8].

Quality of life

QoL refers to an individual’s subjective perception of well-being in different life domains. For the adolescent population, a broader coverage of this concept is preferred, including measures of QoL related to family, friends, and school [23]. For this reason, we use the health-related definition of QoL, which views it as “a psychological construct which describes the physical, mental, social, psychological and functional aspects of well-being and function from the patient perspective” [24].

Most of the related research have found that girls report lower QoL compared to boys [4, 25], with one exception for disadvantaged youths, where no sex difference has been found [26]. Past research generally reported decreasing QoL and subjective well-being at younger ages [4, 25]. Moreover, both personal and environmental psychosocial risk factors may influence an individual's sense of well-being, thereby affecting QoL [25]. Previous experiences of maltreatment, mental health problems, and other stressful life events have also been associated with poor QoL [20, 27, 28]. The sparse research on adolescents living in RYC report significantly poorer QoL than adolescents living with their biological families [4, 25]. Jozefiak and Kayed [5] studied the same population as in the current study and found that, compared to the general population, adolescents in RYC reported lower scores in the life-domains of physical well-being (PWB), emotional well-being (EWB), self-esteem and friends, which raise major concerns. Greger and colleagues [20] also found a dose–response relationship between the number of types of ACE and QoL, which has also been reported in other populations [29, 30]. Despite these findings and the fact that several researchers have stated a need for more in-depth investigations of the potential predictors of high-risk adolescents’ QoL [4, 25, 31], research on the potentially moderating factors for QoL among adolescents with experiences of maltreatment and polyvictimization is still lacking.

Perceived social support

Perceived social support is defined as the availability of people who make one feel cared about, valued, and loved [32]. Having social relationships with others is a basic human need and is important for a healthy development, as early relational experiences affect and form the quality of and expectations in later social relationships [33, 34]. For adolescents in RYC, a previous lack of stable social relationships and reliable care could cause a mistrust of others and insecurity in their present social relationships [3, 11]. However, new social relationships can still develop positively, as previous experiences are not automatically transferred into new social relationships, and the strength of each social relation is person-specific [31, 35]. For adolescents in RYC, identifying the potential possible social support providers is particularly important, as they may require substitute support persons in the case of inadequate parental support.

One study on the same population as the current study found that adolescents in RYC perceive less social support than adolescents in the general population, with mothers, friends, and RYC staff serving as the important social support providers [8]. Additionally, boys in RYC tend to perceive lower social support than girls [36], whereas girls tend to be more available for emotional closeness in social relationships than boys [37, 38]. Social support, however, is especially important for these vulnerable adolescents, as it has been found to reduce feelings of stress and can facilitate successful adaptation to new situations [39, 40]. Social support is also positively associated with well-being [41], adjustment [36], mental health [42, 43], and educational achievement [44]. However, despite the importance of social support and the risks associated with inadequate support, studies on the associations between social support and QoL for adolescents living in RYC remain sparse.

Quality of life and perceived social support

Social relationships [33, 45] have been found to influence adolescents’ QoL [46], with research suggesting that having a high number of available social resources helps ensure that vulnerable adolescents maintain good QoL. Mendonça and Simões [26] found positive associations between QoL and the availability of social support from multiple sources among socioeconomically disadvantaged youth, but only allowed for three social support categories with poor differentiation among important sources. Alriksson-Schmidt and colleagues [47] found that the availability of several social resources could lead to better QoL for adolescents with mobility disability. However, neither of these studies included adolescents in the out-of-home care setting, nor did they investigate the number of different support persons or individual social support providers.

For adolescents in the general population, family members play a salient role in QoL and overall life-satisfaction [48, 49], especially parents who help in monitoring and developing their communication skills [50]. As adolescents in RYC are separated from their biological families, identifying other adults who can serve as a partial substitute for the lack of parental presence and support, such as the RYC staff [51], is important. The RYC staff can serve as valuable contributors to the overall well-being of adolescents living in RYC [37]. In fact, adolescents who stayed longer in RYC reported higher QoL than those with shorter stays [25], possibly suggesting that secure attachments with the RYC staff can develop over time. Another study found that interpersonal relationships with parents, staff, and friends are the most frequently reported determinants of better overall QoL for adolescents in RYC [52]. However, given the lack of empirical evidence, these hypotheses need further investigation. To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated the unique effects of parental, friend, or staff support on the QoL of adolescents living in RYC.

While the number of childhood adversities has been found to be positively associated with poorer QoL [20], the potential moderating factors should also be investigated, including perceived social support. In a recent study on the QoL of adolescents in the general population, the association between maltreatment and QoL remained significant, and perceived social support moderated the negative effects of the maltreatment [29]. However, other studies claim that perceiving social support is insufficient as a protective factor for adolescents who have experienced severe child maltreatment and abuse [53, 54]. Currently, the potential moderating effect of perceived social support for high-risk adolescents living in RYC has yet to be adequately investigated.

Aims of the current study

The current study aims to investigate the associations between perceived social support and QoL, as well as the potential moderating effect of perceived social support on maltreated adolescents’ QoL. Hence, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

(1)

Perceived social support from a high number of support persons is associated with better QoL.

-

(2)

The association between perceived social support and QoL depends on the individuals from whom the adolescents perceive social support.

-

(3)

Perceived social support moderates the negative effects of maltreatment on adolescents’ QoL.

As previous research has established the importance of sex and age in relation to measuring QoL [55], sex and age differences will be controlled for in the current study.

Methods

Data

Setting

The Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth, and Family has the responsibility for overseeing the operation of RYC facilities in Norway, where children and adolescents aged 12–23 years (> 18 only if volunteering for placement) are placed according to the Child Welfare Act. These placements are often due to family problems, parents’ inability to provide care, parents’ substance use, or adolescent behavior problems [6, 56]. The adolescents in the current sample reported the following main reasons for their first out-of-home placement: problems between the adolescent and the parents (43.4%), such as constant arguing, disagreements, or violence, and individual adolescent (30.6%) or parental (25.6%) characteristics, referring to extensive problems with, for example, anger or violence, apart from wide ranging mental health problems or issues related to substance use.

Norwegian RYC institutions usually house 3–5 residents at a time, with the aim of providing a home-like, caring environment for the adolescents. As they are not primary treatment facilities, direct services are provided by other community agencies. The institutional staff are responsible for the everyday care of the adolescents and serve as substitute parents as they are the adolescents' primary caregivers while living in RYC. Aside from providing care, monitoring, and support, the staff also initiate participation in school (almost 70% attend school) and leisure activities for the adolescents. For each adolescent, one of the staff members functions as a primary contact with the overall responsibility for the adolescent while living in RYC [57]. The staff either work three shifts per day (daytime, evening, or night shift) or they stay at the institutions for 3–7 days before having a longer period off. The educational backgrounds of the staff members differ, as only 50% are required to have relevant education [57]. Over 90% of the adolescents also have contact with their parents or previous caregivers while living in RYC.

Study population

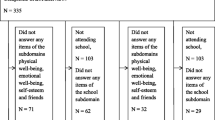

The data used in the current study were obtained from the Norwegian research project entitled Mental Health in Adolescents Living in Residential Youth Care [21]. All adolescents aged 12–23, living in RYC facilities in Norway, and fulfilling the inclusion criteria, were asked to participate in the study. Exclusion was due to both individual and institutional characteristics, described in detail in Fig. 1. In short, 86 institutions accepted participation (N = 601), whereas 201 adolescents did not give their consent. Anonymous CBCL-scores (Child Behavior Checklist) were collected for the non-participants, making it possible to perform an attrition analysis, which shows the statistically significant representativeness of participants on mental health scores (please see Jozefiak et al. [21] for further information). A total of 400 adolescents agreed to participate in the study, giving a response rate of 67%. Table 1 presents the main characteristics of the sample. Of those included in the study, 304 completed the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ), 300 completed the Kinder Lebensqualität Fragebogen (KINDL-R), and 298 adolescents completed both questionnaires. Attrition analysis showed that completers and non-completers had similar distributions for sex, age, age at first out-of-home placement, and total CBCL score [see Additional file 1].

Flow chart for the inclusion of participants. Not able to contact = if the institutional staff did not respond to repeated approaches about participation over a period of several months. There were no significant differences between participating and non-participating institutions with regard to geography and ownership. RYC = Residential Youth Care; SSQ = Social Support Questionnaire; QoL = Quality of Life

Procedures

All RYC institutions in Norway were randomly arranged in a database, and representative staff were contacted personally by research assistants. In the period between 2011 and 2014, four trained research assistants with comprehensive education and work experience with children and their families carried out the data collection. Adolescents, primary contacts, and leaders at the institutions completed different questionnaires. When necessary, breaks were adapted for the adolescents, and data collection was conducted over two days to minimize the strain. Each adolescent was compensated with 500 NOK, and four randomly chosen adolescents won an I-phone.

Instruments

The Kinder Lebensqualität Fragebogen (KINDL-R)

To measure QoL, we used the Norwegian translation of The Kinder Lebensqualität Fragebogen revised version (KINDL-R) [23], a well-established instrument used in numerous clinical and epidemiological studies. KINDL-R consists of 24 items divided into six subscales: Physical well-being (PWB), Emotional well-being (EWB), Self-esteem, Family, Friends, and School. Each item addresses the child’s experiences over the past week rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). A sum score is calculated for each subscale and for the overall score, where a higher score indicates better QoL (max = 100). The questionnaire has shown good scale fit and satisfactory internal consistency [58] and test–retest reliability [59]. For the present study, the subscales Family, School, and Friends were excluded. The Family subscale, which include questions related to family life in the past week, was not relevant for the current population. The School subscale was removed for the main analysis, because 29% of the participants were not attending school, although additional analyses were conducted separately for the participants who were currently enrolled (N = 193). The Friend subscale was removed due to conceptual overlap with the SSQ (e.g., “I was a success with my friends” and “I got along well with my friends”).

Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ)

The Social Support Questionnaire measures three aspects of perceived social support, including perceived number of different types of support persons (SSQ-N), social support satisfaction (SSQ-S), and perceived social support from different social support providers. As the satisfaction scale only measures satisfaction with the perceived support in each situation, not individually for each provider, and that the adolescents are generally satisfied with the support perceived [8], we chose not to include this scale in our analyses. Instead, in the current study, we used a short 5-item version [60] developed from the original 27-item version [32]. Briefly, the questionnaire examines who the adolescents can turn to (nine possible support persons) in five hypothetical situations, including different social support domains. First, the SSQ-N score is calculated by counting the number of different types of support persons listed over the five items. This score is then divided by the number of items to exclude overlapping counts of the support persons for the overall SSQ-N score. This score measures the perceived breadth of the respondents' social support network. Second, perceived social support from different providers can be investigated separately and compared to those adolescents not perceiving support from the same group of providers. More detailed information on the SSQ is given in Singstad et al. [43]. The internal consistencies for the scores in the currently used version of the SSQ were α = 0.79 for SSQ-N and α = 0.76 for SSQ-S.

Childhood adversity

Information about childhood adversity was drawn mainly from selected questions from a semi-structured psychiatric interview (The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment/CAPA). In addition, a measure of household dysfunction was created based on information from a questionnaire completed by the adolescents. Those who confirmed that their parents had a history of mental health problems, often got drunk or used drugs, or that they had been removed from the family home because of parental crime, alcohol or drug abuse, or psychiatric problems received a positive score on household dysfunction. We constructed a scale wherein the numbers of types of adversities were added. These adversities included the following: witness of violence, victim of physical violence, victim of family violence, victim of sexual abuse, and household dysfunction. Greger et al. [2] provided specific information about childhood adversity in the current sample.

Statistical analyses

We used linear regression analyses with the overall QoL score and each of the three subscale scores, separately, as dependent variables, with the overall SSQ-N score serving as the covariate, adjusting for age. Independent samples t-test was used to investigate mean level differences in overall QoL and for each subscale score dependent of indications of support from each type of social support provider. To investigate the possible moderating effect of a perceived social support to maltreated adolescents’ QoL, we used linear regression with overall QoL as the dependent variable as well as the social support variable and the childhood adversity scale and their interactions as covariates, adjusting for age. The normality of residuals was checked by visual inspection of the Q-Q plots [61]. All analyses were conducted separately for girls and boys.

These analyses were performed using SPSS version 26. Results are regarded statistically significant where p values < 0.05. We report 95% confidence intervals (CI) where relevant.

Ethics

The project was approved by The Norwegian Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (Project 2014/1516). The approved procedures were used in the recruitment of participants, and all participants (including the primary caregiver for those under the age of 16) had to sign an informed consent form before participation.

Results

Quality of Life and Breath of Support Network

As detailed in Table 2, for girls, a higher number of different types of support persons (overall SSQ-N) was significantly associated only with higher self-esteem QoL (p = 0.014). For boys, significant associations were found with higher overall QoL (p = 0.005), EWB (p = 0.020), and self-esteem (p = 0.001). A separate analysis on those participating in school (N = 193) revealed no association with the school QoL.

Quality of Life and Different Providers of Social Support

As detailed in Table 3, perceiving social support from parents was not significantly associated with higher overall QoL nor for any subscale for either girls or boys. Girls perceiving staff support reported significantly higher self-esteem compared to those who did not perceive staff support (p = 0.038). For boys, perceiving social support from staff was not significantly associated with any of the QoL scores. Whereas perceiving friend support was significantly associated with an increase in all QoL scores for girls, including overall QoL (p = 0.002), PWB (p = 0.012), EWB (p = 0.010), and self-esteem QoL (p = 0.003), no increase in the QoL scores for boys were found.

Additional analyses for the school participants’ reports on the School subscale for girls found associations between overall QoL and perceiving staff support (p = 0.029) and friend support (p = 0.001). No significant associations were found for perceived social support from individual support providers and overall QoL for boys in the school-participant group.

Moderating effect of perceived social support on maltreated adolescents’ QoL

Table 4 presents the results from analyses to test the moderation by different social support aspects in the relationship between childhood adversity and overall QoL. As none of the relevant interaction terms were statistically significant, and the corresponding confidence intervals were wide, the results did not confirm moderation by either overall SSQ-N or perceiving support from any of the sources considered here.

Discussion

Our results showed that QoL is associated with perceived social support for adolescents living in RYC, although there are differences between girls and boys. For the number of different types of support persons, most associations to QoL were found for boys, namely, for overall QoL, EWB, and self-esteem. For girls, significant associations were only observed for self-esteem. For different providers of support, significant associations were found for girls between the self-esteem and perceiving staff support and for all QoL aspects when perceiving friend support. For boys, no significant associations were found in relation to different providers of support. In addition, perceiving social support did not moderate the negative effects of previous experiences of maltreatment and polyvictimization on adolescents’ QoL.

Quality of life and breath of support network

For boys living in RYC, a higher number of different types of support persons is associated with better QoL in several domains, including overall QoL, EWB, and self-esteem. This is not a surprising finding, as EWB covers the degree of happiness, loneliness, and insecurity. Boys have previously been reported to seek activity in their interactions and seem to benefit the most from receiving social support through group activities [62]. Therefore, having several different support providers who are available in multiple areas can, for example, improve their degree of happiness and contribute to less feelings of loneliness. This also applies to the association with self-esteem, which measures, for example, feelings of worth and satisfaction with one`s own performance. The presence of positive relationships and having a sense of acceptance and being valued through supportive relationships are likely to increase the adolescents’ self-esteem [32, 63]. This also applies to girls based on the significant association found between self-esteem and the breadth of their social network.

Quality of life and different providers of social support

For adolescent girls' QoL, perceiving social support from some specific social support providers (i.e., institutional staff and friends) appears important. Girls perceiving staff support reported higher self-esteem compared to those without this support, although the result is not highly significant. One can assume that institutional staff have an important contribution in supporting these girls in everyday life, possibly fostering a belief in themselves and their own capacity. As girls report a higher need of closeness and one-to-one interactions in their supportive relationships compared to boys [37, 64], the presence and stability of the institutional staff are crucial in this context. Whereas parents most often are the important contributors to children’s self-esteem [65], it might be that the institutional staff can substitute for the lack of parental presence for girls while they live in RYC, which would be encouraging.

Additional analyses on the school participants found significant associations between perceived staff support and overall QoL. Adolescents attending school while in RYC are younger (mean age = 16.0) than those who are not attending school (mean age = 16.9, p < 0.01). Therefore, given that younger adolescents are often in need of significant support from their primary caregivers [8, 66], it is not surprising that the RYC staff are important contributors to these girls’ feelings of security and being cared for in the absence of parental support [8, 67]. The fact that the RYC staff can promote positive outcomes, such as higher well-being for adolescents living in RYC, is consistent with previous research [40, 68, 69]. It is a well-known fact that friends become increasingly important with higher age [66, 70], so the significant associations between friend support and QoL across all domains for girls are not surprising, as they coincide with previous research [52]. Girls mostly report valuing closeness and the emotional aspects of social support through one-to-one interactions [38, 62, 70], so that they consider being cared for, valued, and accepted by friends as particularly important during adolescence [8, 70]. This is also associated with better QoL for girls. For boys, perceiving social support from individual providers did not appear to play a role in their QoL.

The potential moderating effect of perceived social support on maltreated adolescents QoL

We did not find any evidence to support the hypothesis that perceived social support moderated the effect of maltreatment on these adolescents’ QoL. Adolescents living in RYC are particularly vulnerable, as they have simultaneous experiences of maltreatment, household dysfunction, and out-of-home placements. We know that they report poor QoL compared to peers in the general population and that there is a dose–response relationship between the number of events and poorer QoL [20]. Previous research have found that a higher number of childhood adversities reduces the likelihood of social support being a moderator for the adolescents’ poor QoL [53, 54]. The current lack of statistically significant results concerning both the number of different types of support persons and individual support providers strengthens the knowledge of the critical long-term consequences of growing up with child maltreatment and household dysfunction [1, 20]. Perceiving social support does not seem by itself to protect these vulnerable adolescents’ QoL while living in RYC.

Limitations

The cross-sectional nature of this study limits the interpretation of our results. First, the current study cannot state the causal relationships between perceived social support and QoL; it can only indicate the need for a longitudinal study of these associations. Second, more background variables concerning the respondents, such as mental health before and at the time of placement, age at each placement, length of stay in each out-of-home placement, and frequency of contact with significant others outside the RYC, would have been beneficial and could have provided deeper insights. In addition, we did not have the opportunity to include parents as respondents in measuring QoL, because the adolescents did not live at home, which led to the exclusion of considering family functioning. School functioning was also excluded, because it did not apply to a portion of those in RYC. Furthermore, we lacked measurement of QoL for about 25% of the adolescents participating in the overall study, but the analytic sample appeared to be representative because distributions of sex, age, and internalizing and externalizing mental health problems did not differ between the completers and the non-completers.

The SSQ also has some limitations. In measuring perceived social support, additional sources of social support could be addressed, including the opportunity to add unnamed sources. This would have provided deeper insights into the role of different social support providers in improving the QoL of adolescents in RYC.

Future practice

As research on the associations between perceived social support and QoL for this vulnerable group of adolescents is generally lacking, results should be helpful in developing practices to provide the best care possible in RYC and in planning further research. Given that maltreatment is common among these adolescents [20], it is reasonable to assume a high prevalence of social skill deficit in this group [71]. As social support is associated with increased QoL, more specifically to a wider social network for boys and for friend and staff support for girls, further development of social skills and the conduct of social skills training should be prioritized in RYC. An increase in these adolescents’ social skills might contribute to both maintaining and establishing social relationships while living in RYC. The RYC staff also have an important role in ensuring the maintenance of the already established social networks for these adolescents, so they can benefit from their positive effects while living in RYC. At the same time, one should be cautious regarding the possible negative influence some friends could have on the adolescents’ behaviors [72]. Arenas for socialization, preferably close to the institutions, should be prioritized. Finally, the length of the residential stays influence adolescents’ well-being, adjustment, and relations to the staff [36]. Thus, disruptions in the RYC placement should be prevented.

Given that perceiving social support does not appear by itself to moderate the negative effects of maltreatment and polyvictimization on these adolescents’ QoL, other initiatives should be explored to help them improve their QoL. Knowledge about other factors that could moderate the association between the negative effects of maltreatment and QoL would be highly valuable, as it can broaden the scope of possible solutions to help these vulnerable adolescents. Finally, these findings highlight the need for more research on potentially protective factors for adolescents in RYC.

Conclusions

Adolescents living in RYC typically have several previous negative life experiences and face a high prevalence of current difficulties and challenges, which are likely to have a negative effect on their QoL. Therefore, increasing these adolescents’ QoL should be a priority for national authorities as they work on providing the best care possible in RYC. The current study suggests that adolescents’ social support network has an important contribution to their QoL. However, various aspects of social support appear differentially beneficial for girls and boys. A larger network of different types of support persons appears significant for boys, whereas specific providers of social support (especially friends) providing one-to-one interactions appear most beneficial for girls. In summary, these findings expand our current knowledge of the potential critical factors contributing to adolescents’ QoL while living in RYC facilities.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Adverse childhood experiences

- CAPA:

-

The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment

- CBCL:

-

Child Behavior Checklist

- CWS:

-

Child welfare services

- EWB:

-

Emotional well-being

- KINDL-R:

-

The Kinder Lebensqualitat Fragebogen revised version

- PWB:

-

Physical well-being

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RYC:

-

Residential youth care

- SSQ:

-

Social support questionnaire

- Overall SSQ-N:

-

Total number of different types of support persons

- SSQ-S:

-

Social support satisfaction

References

Kerker BD, Zhang J, Nadeem E, Stein REK, Hurlburt MS, Heneghan A, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health, chronic medical conditions, and development in young children. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(5):510–7.

Greger HK, Myhre AK, Lydersen S, Jozefiak T. Previous maltreatment and present mental health in a high-risk adolescent population. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;45:122–34.

Brown LS, Wright J. Attachment theory in adolescence and its relevance to developmental psychopathology. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2001;8(1):15–32.

Damnjanovic M, Lakic A, Stevanovic D, Jovanovic A, Jancic J, Jovanovic M, et al. Self-assessment of the quality of life of children and adolescents in the child welfare system of Serbia. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2012;69:469–74.

Jozefiak T, Kayed NS. Self- and proxy reports of quality of life among adolescents living in residential youth care compared to adolescents in the general population and mental health services. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):104.

Backe-Hansen E, Bakketeig E, Gautun H, Grønningsæter AB. Institusjonsplassering - siste utvei? : betydningen av barnevernsreformen fra 2004 for institusjonstilbudet. (Placement in institutions - the last opportunity. The importance of the child welfare reform in 2004 for placement policy in institutions.). Oslo: Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring; 2011.

Leipoldt JD, Harder AT, Kayed NS, Grietens H, Rimehaug T. Determinants and outcomes of social climate in therapeutic residential youth care: A systematic review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;99:429–40.

Singstad MT, Wallander JL, Lydersen S, Wichstrøm L, Kayed NS. Perceived social support among adolescents in Residential Youth Care. Child Fam Soc Work. 2020;25:384–93.

Collin-Vézina D, Coleman K, Milne L, Sell J, Daigneault I. Trauma experiences, maltreatment-related impairments, and resilience among child welfare youth in residential care. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2011;9(5):577–89.

Wright MOD, Folger SF. Creating a safe haven following child maltreatment : the benefits and limits of social support. In: Teti DM, editor. Parenting and family processes in child maltreatment and intervention. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 23–34.

Tyler S, Allison K, Winsler A. Child neglect: developmental consequences, intervention, and policy implications. Child Youth Care Forum. 2006;35(1):1–20.

Lehmann S, Havik OE, Havik T, Heiervang ER. Mental disorders in foster children: a study of prevalence, comorbidity and risk factors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013;7(1):39.

Brannstrom L, Forsman H, Vinnerljung B, Almquist YB. The truly disadvantaged? Midlife outcome dynamics of individuals with experiences of out-of-home care. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;67:408–18.

Romano E, Babchishin L, Marquis R, Frechette S. Childhood maltreatment and educational outcomes. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16(4):418–37.

Villodas MT, Litrownik AJ, Newton RR, Davis IP. Long-Term Placement trajectories of children who were maltreated and entered the child welfare system at an early age: consequences for physical and behavioral well-being. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;41(1):46–54.

Holmbeck GN. A developmental perspective on adolescent health and illness: an introduction to the special issues. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(5):409–16.

Gaspar T, Matos MG, Pais R, Jose L, Leal I, Ferreira A. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents and associated factors. J Cogn Behav Psychother. 2009;9(1):33–48.

Bederian-Gardner D, Hobbs SD, Ogle CM, Goodman GS, Cordón IM, Bakanosky S, et al. Instability in the lives of foster and nonfoster youth: Mental health impediments and attachment insecurities. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;84:159–67.

Schuengel C, Oosterman M, Sterkenburg PS. Children with disrupted attachment histories: interventions and psychophysiological indices of effects. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2009;3(1):26.

Greger HK, Myhre AK, Lydersen S, Jozefiak T. Child maltreatment and quality of life: a study of adolescents in residential care. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):74.

Jozefiak T, Kayed NS, Rimehaug T, Wormdal AK, Brubakk AM, Wichstrøm L. Prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders among adolescents living in residential youth care. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25:33–47.

González-García C, Bravo A, Arruabarrena I, Martín E, Santos I, Del Valle JF. Emotional and behavioral problems of children in residential care: screening detection and referrals to mental health services. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;73:100–6.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. KINDL-R. Questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents—revised version 2000.2000. http://www.kindl.org.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. Assessing health-related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: first psychometric and content analytical results. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(5):399–407.

Nelson TD, Kidwell KM, Hoffman S, Trout AL, Epstein MH, Thompson RW. Health-related quality of life among adolescents in residential care: description and correlates. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84(3):226–33.

Mendonça C, Simões F. Disadvantaged youths’ subjective well-being: the role of gender, age, and multiple social support attunement. Child Indic Res. 2019;12(3):769–89.

Lanier P, Kohl PL, Raghavan R, Auslander W. A preliminary examination of child well-being of physically abused and neglected children compared to a normative pediatric population. Child Maltreat. 2015;20(1):72–9.

Dey M, Landolt MA, Mohler-Kuo M. Health-related quality of life among children with mental disorders: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(10):1797–814.

Chan KL, Chen M, Chen Q, Ip P. Can family structure and social support reduce the impact of child victimization on health-related quality of life? Child Abuse Negl. 2017;72:66–74.

Weber S, Jud A, Landolt MA. Quality of life in maltreated children and adult survivors of child maltreatment: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(2):237–55.

Bronsard G, Lançon C, Loundou A, Auquier P, Rufo M, Tordjman S, et al. Quality of life and mental disorders of adolescents living in French residential group homes. Child Welfare. 2013;92(3):47–71.

Sarason IG, Levine HM, Basham RB, Sarason BR. Assessing social support: The Social Support Questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44(1):127–39.

Helgeson VS. Social support and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(1):25–31.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol 3: Loss: sadness and depression. London: Pimlico; 1998.

Carlson EA, Sampson MC, Sroufe LA. Implications of attachment theory and research for developmental-behavioral pediatrics. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24(5):364–79.

Hoffnung Assouline AA, Attar-Schwartz S. Staff support and adolescent adjustment difficulties: The moderating role of length of stay in the residential care setting. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;110:104761.

Costa M, Melim B, Tagliabue S, Mota CP, Matos PM. Predictors of the quality of the relationship with caregivers in residential care. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;108:104579.

Lanctôt N, Lemieux A, Mathys C. The value of a safe, connected social climate for adolescent girls in residential care. Resid Treat Child Youth. 2016;33(3–4):247–69.

Cheng Y, Li X, Lou C, Sonenstein FL, Kalamar A, Jejeebhoy S, et al. The association between social support and mental health among vulnerable adolescents in five cities: findings from the study of the well-being of adolescents in vulnerable environments. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(6, Supplement):S31–8.

Sciaraffa MA, Zeanah PD, Zeanah CH. Understanding and promoting resilience in the context of adverse childhood experiences. Early Child Educ J. 2018;46(3):343–53.

Chu PS, Saucier DA, Hafner E. Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2010;29(6):624.

Rueger SY, Malecki CK, Pyun Y, Aycock C, Coyle S. A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychol Bull. 2016;142(10):1017–67.

Singstad MT, Wallander JL, Lydersen S, Kayed NS. Perceived social support and symptom loads of psychiatric disorders among adolescents in residential youth care. Soc Work Res. 2020; in press.

Rothon C, Goodwin L, Stansfeld S. Family social support, community “social capital” and adolescents’ mental health and educational outcomes: a longitudinal study in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(5):697–709.

Petito F, Cummins RA. Quality of life in adolescence: the role of perceived control, parenting style, and social support. Behav Change. 2000;17(3):196–207.

Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, Larson JL. Conceptual Model of Health-Related Quality of Life. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37(4):336–42.

Alriksson-Schmidt AI, Wallander J, Biasini F. Quality of life and resilience in adolescents with a mobility disability. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;32(3):370–9.

Jozefiak T, Wallander JL. Perceived family functioning, adolescent psychopathology and quality of life in the general population: a 6-month follow-up study. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(4):959–67.

Piko BF, Hamvai C. Parent, school and peer-related correlates of adolescents’ life satisfaction. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2010;32(10):1479–82.

Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26(1):399–419.

Schiff M, Nebe S, Gilman R. Life satisfaction among israeli youth in residential treatment care. Br J Soc Work. 2005;36(8):1325–43.

Swerts C, De Maeyer J, Lombardi M, Waterschoot I, Vanderplasschen W, Claes C. “You shouldn’t look at us strangely”: an exploratory study on personal perspectives on quality of life of adolescents with emotional and behavioral disorders in residential youth care. Appl Res Qual Life. 2019;14(4):867–89.

Lo CKM, Ho FKW, Yan E, Lu Y, Chan KL, Ip P. Associations between child maltreatment and adolescents’ health-related quality of life and emotional and social problems in low-income families, and the moderating role of social support. J Interpers Violence. 2019:0886260519835880.

Folger SF, Wright MOD. Altering risk following child maltreatment: Family and friend support as protective factors. J Fam Violence. 2013;28(4):325–37.

Wallander JL, Koot HM. Quality of life in children: a critical examination of concepts, approaches, issues, and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;45:131–43.

Kayed NS, Jozefiak T, Rimehaug T, Tjelflaat T, Brubakk AM, Wichstrøm L. Resultater fra forskningsprosjektet psykisk helse hos barn og unge i barneverninstitusjoner (Results from the research project "Mental Health in Adolescents living in Child Welfare Institutions"). Trondheim: NTNU, Regionalt kunnskapssenter for barn og unge - Psykisk helse og barnevern; 2015.

Bufdir. Kvalitet i barneverninstitusjoner (Quality in child welfare institutions). [Oslo]: Bufdir; 2010. 121 s. p.

Bullinger M, Brutt AL, Erhart M, Ravens-Sieberer U, BELLA Study Group. Psychometric properties of the KINDL-R questionnaire: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17:125–32.

Jozefiak T, Larsson B, Wichstrøm L, Mattejat F, Ravens-Sieberer U. Quality of Life as reported by school children and their parents: a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6(1):34.

Wichstrøm L, Hegna K. Sexual orientation and suicide attempt: a longitudinal study of the general Norwegian adolescent population. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(1):144.

Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall/Pearson; 2010.

Youniss J, Smollar J. Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers and friends. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987.

Birndorf S, Ryan S, Auinger P, Aten M. High self-esteem among adolescents: longitudinal trends, sex differences, and protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(3):194–201.

Frey CU, Röthlisberger C. Social support in healthy adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 1996;25(1):17–31.

Arslan C. Anger, self-esteem, and perceived social support in adolescence. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2009;37(4):555–64.

Bokhorst CL, Sumter SR, Westenberg PM. Social support from parents, friends, classmates, and teachers in children and adolescents aged 9 to 18 years: who is perceived as most supportive? Soc Dev. 2010;19(2):417–26.

Moore T, McArthur M, Death J, Tilbury C, Roche S. Sticking with us through it all: the importance of trustworthy relationships for children and young people in residential care. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;84:68–75.

Schütz FF, Castellá Sarriera J, Bedin LM, Montserrat C. Subjective well-being of children in residential care centers: Comparison between children in institutional care and children living with their families. Psicoperspectivas Individuo y Sociedad. 2015;14(1):19–30.

Mota CP, Matos PM. Adolescents in institutional care: significant adults, resilience and well-being. Child Youth Care Forum. 2015;44(2):209–24.

Levpušček MP. Adolescent individuation in relation to parents and friends: age and gender differences. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2006;3(3):238–64.

Lum JAG, Powell M, Snow PC. The influence of maltreatment history and out-of-home-care on children’s language and social skills. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;76:65–74.

White R, Renk K. Externalizing behavior problems during adolescence: an ecological perspective. J Child Fam Stud. 2012;21(1):158–71.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the RYC adolescents and the RYC staff members for their participation in this study.

Funding

This research was funded by means from the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs, the Norwegian Directorate for Health and Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MTS conceived of the study and its design, carried out the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. JW conceived in the study design, interpretation of the results and contributed in writing the manuscript. HG contributed in the study design, interpretation of results, and in writing the manuscript. SL supervised the statistical analyses. NSK conceived of the study and its design and contributed in interpretation of results and writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The project was approved by The Norwegian Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics. Approved procedures were used in recruitment of participants, and all participants (including primary caregiver for those under the age of 16) had to sign an informed consent before participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Descriptive statistics for completers and non-completers of the Social Support Questionnaire.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Singstad, M.T., Wallander, J.L., Greger, H.K. et al. Perceived social support and quality of life among adolescents in residential youth care: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 19, 29 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01676-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01676-1