Abstract

Background

This review aims to critically appraise and compare the measurement properties of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-specific health-related quality of life instruments.

Methods

Medline, EMBASE and ISI Web of Knowledge were searched from their inception to May 2016. IBD-specific instruments for patients with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis or IBD were enrolled. The basic characteristics and domains of the instruments were collected. The methodological quality of measurement properties and measurement properties of the instruments were assessed.

Results

Fifteen IBD-specific instruments were included, which included twelve instruments for adult IBD patients and three for paediatric IBD patients. All of the instruments were developed in North American and European countries. The following common domains were identified: IBD-related symptoms, physical, emotional and social domain. The methodological quality was satisfactory for content validity; fair in internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, hypotheses testing and criterion validity; and poor in measurement error, cross-cultural validity and responsiveness. For adult IBD patients, the IBDQ-32 and its short version (SIBDQ) had good measurement properties and were the most widely used worldwide. For paediatric IBD patients, the IMPACT-III had good measurement properties and had more translated versions.

Conclusions

Most methodological quality should be promoted, especially measurement error, cross-cultural validity and responsiveness. The IBDQ-32 was the most widely used instrument with good reliability and validity, followed by the SIBDQ and IMPACT-III. Further validation studies are necessary to support the use of other instruments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are characterized by chronic, uncontrolled and relapsing inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, which encompasses Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is defined as a broad, multidimensional concept comprising patients’ physical health (including disease), psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and relationship to their environment [1, 2]. The evaluation of HRQoL for patients with IBD in clinical research and clinical practice enhances the understanding of the disease impact and the effects of treatments on the disease. Thus, the evaluation of HRQoL should be recognized as an important outcome indicator by patients and their clinicians.

Up to now, a large number of IBD-specific HRQoL instruments have been developed and validated for the IBD patients [3,4,5,6,7]. These instruments have been used to assess patients’ understanding of IBD symptoms and the subjective perception of the illness in clinical practice and research [3, 4]. They have also been used to compare the effect of treatment strategies and to provide evidence for health policy makers [3,4,5].

Several researchers have conducted reviews that measure the HRQoL of patients with IBD [3,4,5,6,7,8]. However, the reviews only enrolled some of the instruments, while other instruments are commonly ignored. The measurement properties and methodological quality of measurement properties should be evaluated systematically for clinical practitioner and researchers. We aimed to comprehensively collect all of the eligible IBD-specific HRQoL instruments to gain an understanding of their measurement properties. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to critically appraise and compare the measurement properties of the instruments to help clinicians and researchers select an appropriate instrument.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study was conducted following the guideline of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA statement) [9]. Articles were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) Types of patients: Patients diagnosed as CD, UC or IBD were enrolled. Patients with other diseases (infectious colitis, ischemic colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, etc.) were excluded. (2) Types of instruments: The HRQoL instruments developed and validated for patients with CD, UC or IBD were eligible. HRQoL was defined as a broad, multidimensional concept comprising patients’ physical health (including disease), psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and relationship to their environment. Both the self-administered and rater-administered instruments were included. The instruments for child or adult patients were included. (3) Types of languages: The full-text articles were published in English. General HRQoL instruments were excluded, such as the SF-36. Disease-specific instruments not related or only partially related to IBD were also excluded, such as the gastrointestinal quality of life index [10].

Literature search

The following relevant electronic databases were searched for English-language articles: Medline (via Pubmed) and EMBASE. The search period was from the inception of the databases to May 31th 2016. The search strategy for Medline (see Additional file 1: Appendix S1) consisted of 3 types of search terms for the following: (1) IBD, UC or CD; (2) HRQoL; and (3) measurement properties. The latter two filters were developed according to the syntax established by Kotecha et al. [11].

In addition, Google Scholar was used to search for relevant articles and literature. The citations of the reviews and the references of included articles were also checked. The patient-reported outcome and quality of life instruments database (website: https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/) was searched for eligible instruments. Two review authors (XLC, FBL) independently performed the literature search. Disagreements between the two authors were resolved by discussion with another author (LHZ).

Literature extraction

A set of questions regarding the characteristics of the instruments were drafted. The characteristics were as follows: Which type of disease does the instrument assess (IBD, UC or CD)? How is the instrument administered (self-administered or rater-administered)? How long does it take to complete (completion time)? At what time does it measure the HRQoL of the patients (recall period)? How many items does it contain? What is the form of the item (response options: including Likert or visual analogue scale [VAS])? What is the range of the scores? What domains does it contain? Are classical test theory and item response theory applied? Data about the first author, year of publication, the full and abbreviated names of the instrument and the country of origin (the first version) were also collected.

The methodological quality of measurement properties was assessed according to the consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments (COSMIN) checklist with a 4-point scale [12,13,14]. The COSMIN had the following items: internal consistency, reliability (test-retest reliability), measurement error, content validity, structural validity, hypothesis testing, cross-cultural validity, criterion validity and responsiveness. For each instrument, the measurement properties were rated as “poor”, “fair”, “good” or “excellent” based on predefined criteria [12,13,14]. The definitions of measurement properties for measurement properties based on COSMIN checklist are shown in Additional file 1: Appendix S2. The following measurement properties of the instruments were also evaluated: reliability (internal consistency, test-retest reliability), content validity (interviews/focus groups, pilot test), structural validity (convergent/divergent, discriminant), criterion validity and responsiveness.

The methodological quality of measurement properties was based on the original version, except that cross-cultural validity was based on the translated versions. Two of the three review authors (XLC, LHZ or YW) independently performed the article selection, screened and extracted the characteristics of the instruments and assessed the measurement properties. Disagreements between the two authors were resolved by discussion with another author (TWL or XYL).

Results

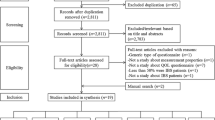

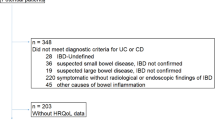

In total, 2075 articles were identified through the search, and 155 potential articles were included for the full text evaluation (Fig. 1). After manually evaluating the full text, 19 IBD-specific HRQoL instruments were identified. The Crohn’s and colitis quality of life questionnaire [15], inflammatory bowel disease impact and symptom scales [16], the Crohn’s disease patient-reported outcomes [17] and ulcerative colitis patient-reported outcomes [18] were excluded due to the lack of full text. At last, 15 articles investigating 15 IBD-specific instruments were included [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Among them, three instruments were for paediatric IBD patients, and the others were for adult IBD patients.

The basic characteristics of the included instruments are shown in Table 1. The quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IMPACT) [19, 34], IMPACT-II [20, 35] and IMPACT-III [21, 36] were IMPACT series instruments. The IMPACT series instruments were for paediatric IBD patients. The 32-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ-32) [22, 37], the 36-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ-36) [24], the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (SIBDQ) [23, 38] and the 9-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ-9) [25] were IBDQ series instruments. All the instruments were developed for patients with IBD, except the Crohn’s life impact questionnaire (CLIQ) for patients with CD [33]. All of the instruments were developed in North American and European countries. All of the instruments were self-administered. Four instruments also had rater-administered versions [22, 23, 25, 29]. Response options in 9 instruments were Likert scales [21,22,23,24,25, 27, 28, 31, 32], and others were VAS scales.

The numbers of domains in the 15 instruments varied from 1 to 6 (Table 2). For the instruments of paediatric IBD, the IMPACT series instruments contained four domains: IBD-related symptoms, physical functioning, emotional functioning and social functioning. For adult IBD patients, some instruments contained the above four domains, whereas some only contained one or two domains. In total, of 55 domains were obtained from all the instruments. (1) Among them, 19 domains were about IBD-related symptoms, which contained bowel or intestinal symptoms (10 domains), systemic symptoms or impairment (6 domains), other symptoms (2 domains) and disease complications (1 domain). (2) Fifteen domains were related to physical functioning or general wellbeing, comprising general quality of life or general wellbeing (5 domains), body image or body stigma (4 domains), functional functioning or impairment (2 domains), energy (2 domains), activity limitations (1 domain) and sexual intimacy (1 domain). (3) Nine domains were about emotional functioning, comprising emotional functioning or impairment (6 domains), disease-related worry (2 domains) and embarrassment (1 domain). (4) Ten domains were about social functioning, containing social functioning (6 domains), social impairment (2 domains) and treatment (2 domains). Another two domains were about information [31] and the total score of the IBDQ-9 (unidimensional) [25].

The methodological quality of measurement properties based on the COSMIN checklist with 4-point scale ratings is shown in Table 3. All of the instruments were developed and assessed based on classical test theory. Item response theory was also used in the IBDQ-9 and CLIQ. (1) Most of the instruments scored “excellent” or “good” for content validity. The items of these instruments were mainly from interviews with patients, review of the literature and professional experience. The pilot study was used to ensure the applicability of the items in the seven instruments. The domains of these instruments mainly contained IBD-related symptoms, physical, emotional and social functioning (Table 2). For example, the IBDQ-32 contained bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional and social domains [22]. (2) Most of the instruments scored “good” or “fair” for internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, hypotheses testing and criterion validity. For example, structural validity was rated in 12 instruments. Among them, two instruments scored “excellent” [25, 33], three scored “good” [21, 26, 31], five scored “fair” [19, 20, 22,23,24] and two scored “poor” [29, 30]. (3) Most of the instruments scored “fair” or “poor” for measurement error, responsiveness and cross-cultural validity. The reasons for responsiveness scoring “fair” or “poor” included: the magnitude of the correlations or differences was not stated; and the criterion for change was not considered as a reasonable gold standard. The reasons for cross-cultural validity scoring “poor” and “fair” included: whether the two translators work independently was not reported; whether the items translated forward and backward was not reported; how differences between the original and translated versions were resolved was not described in detail; the cultural relevance of the translation was not checked; and differential item function between language groups was not assessed.

The measurement properties of the instruments are shown in Table 4. (1) The IMPACT series instruments (IMPACT, IMPACT-II and IMPACT-III) were used to assess the HRQoL of paediatric IBD patients. The IMPACT series instruments, especially IMPACT-II and IMPACT-III, had good content validity and were translated into other languages. They were easily administered and contained the main domains (symptoms, physical, emotional and social domains). (2) The IBDQ-32 was considered to be of good measurement properties (content validity) and was proven to be valid, reliable and responsive. The IBDQ-32 contained the main domains: symptom, social and emotional domains. Furthermore, the IBDQ-32 was the most widely used and was translated and back-translated into a variety of languages. (3) The rating form of IBD patient concerns (RFIPC) had good content validity, internal consistency and internal consistency and acceptable responsiveness. Although the original version did not report the responsiveness, its responsiveness was confirmed in the translated version [39]. The RFIPC contained symptoms and emotional domains but did not contain emotional or social domains. (4) The SIBDQ, IBDQ-9, Cleveland global quality of life (CGQL), short health scale (SHS), Edinburgh inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (EIBDQ) and Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis questionnaire (CUCQ) were short instruments, which were all easily administered and could be completed in a short time. The IBDQ-9, SIBDQ, CUCQ and SHS had good measurement properties. The SIBDQ and IBDQ-9 were short versions of the IBDQ-32 and IBDQ-36, respectively. The SIBDQ was used in the UK, the US, Germany and Spain [40,41,42,43]. The SIBDQ contained symptoms, emotional and social domains. The IBDQ-9 was used in Spain and Iran [25, 44], which only contained one domain (total score). The SHS contained symptom burden, general wellbeing, disease-related worry and social functioning. The SHS was used in England, Norway and Sweden [45,46,47]. The CUCQ was used only in the UK, which should be further evaluated in other languages [32]. (5) For the IBDQ-36, the Cleveland clinic questionnaire for inflammatory bowel disease (CCQIBD) and Padova inflammatory bowel disease quality of life (PIBDQL), limited evidence was available for their measurement properties.

The translated versions of the instruments are shown in Table 5. (1) For the instruments of paediatric IBD, the IMPACT-II had 3 translated versions [48,49,50]. The IMPACT-III had 4 translated versions [51,52,53,54]. (2) For the instruments of adult IBD, the IBDQ-32 and RFIPC were the most widely used worldwide. The IBDQ-32 has been translated and validated in 93 languages [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] and was found to be reliable and valid in some languages. The IBDQ-32 was also used as an important outcome in randomized controlled trials [71,72,73,74,75]. The RFIPC had at least 6 translated versions [76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. The SIBDQ had 4 translated versions [40,41,42,43]. The IBDQ-9 [44], IBDQ-36 [83, 84], PIBDQL [85] and CGQL [86] also had translated versions.

Discussion

The present review summarizes an overview of 15 IBD-specific HRQoL instruments with respect to their measurement properties and the methodological quality based on the COSMIN checklist.

According to the results of the COSMIN checklist, most of the instruments did not include all the methodological quality. Only content validity was assessed properly in most of the included instruments. Most of the instruments scored “good” or “fair” for internal consistency, reliability, structural validity, hypotheses testing and criterion validity. The information regarding measurement error, responsiveness and cross-cultural validity was limited or was of poor measurement property because they did not reach the required criteria or because of insufficient information. Our results were consistent with other instruments appraised by the COSMIN criteria, such as irritable bowel syndrome-specific QOL instruments [87]; rheumatoid arthritis-specific QOL instruments [88]; and QOL instruments for infants, children and adolescents with eczema [89]. Most of the IBD-specific instruments did not show adequate methodological quality. One reason for this was that most of the IBD-specific HRQoL instruments were developed before 2010. However, COSMIN guidelines were developed approximately 2010 [12,13,14]. Therefore, older articles could not follow COSMIN guidelines, and their measurement properties might be underestimated.

Based on the results of the measurement properties and translated versions of the included instruments, some instruments had good psychometric characteristics and were widely used. (1) For paediatric IBD-specific instruments, most of the measurement properties were tested properly, especially the IMPACT-III [21]. The IMPACT-III had the same items as the IMPACT-II. However, The IMPACT-III was on a 0–4 Likert scale, which was easily understood by children. The IMPACT-III was translated into at least 4 translated versions [51,52,53,54]. The IMPACT-III was recommended to assess the HRQoL for paediatric IBD patients. (2) For the adult IBD instruments, the IBDQ-32 and SIBDQ (short version of IBDQ-32) had good measurement properties. The two instruments had excellent content validity and proved to be valid, reliable and responsive. The two instruments contained symptoms, emotional and social domains. The two instruments were used widely. The IBDQ-32 has been translated and validated in 93 languages. The SIBDQ was used in the UK, the US, Germany and Spain [40,41,42,43]. The IBDQ-9, CGQL, SHS, EIBDQ and CUCQ were all short instruments, which had relatively high methodological quality. However, they had fewer translated versions. The IBDQ-36, CCQIBD, PIBDQL, CGQL and EIBDQ had the lowest measurement properties. The PIBDQL and CGQL instruments were developed and assessed based on IBD patients receiving surgery, and they were translated into other languages. The EIBDQ had not been translated into other languages, which limited its use.

Compared with reviews of IBD-specific instruments published by other authors [3,4,5,6,7,8], our review had the following advantages. (1) Our review included more eligible IBD-specific HRQoL instruments. For example, the review conducted by Alrubaiy et al. enrolled 10 instruments [8]. Among them, only five instruments were about HRQoL instruments, while others were burden or disability instruments, such as the Crohn’s disease burden questionnaire, the IBD disability score and the IBD disability index. (2) Our review fully evaluated the measurement properties, including content reliability, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, measurement error, convergent/divergent, discriminant validity, criterion validity, cross-cultural validity and responsiveness. Previous reviews did not evaluate criterion validity, discriminant validity or cross-cultural validity for each instrument [8]. Criterion validity and discriminant validity are important features for the instrument. Criterion validity reflects the extent to which scores on a particular instrument relate to a gold standard. Discriminant validity refers to how well the scale can discriminate between different features of the participants.

All of the IBD-specific instruments were developed in North American and European countries. This is likely because the highest incidence and prevalence rates of IBD are in Europe and North America [90]. Another reason might be associated with the popularity of the QOL concepts and the standard procedure for QOL development [91, 92]. In developing countries, researchers mainly focused on translating and back-translating the IBD-specific instruments and used them to assess the QOL of IBD patients.

Although there was a lack of consensus regarding the specific domains among all of the instruments, the common domains measured in the instruments were identified: IBD-related symptoms, physical functioning or general wellbeing, emotional functioning and social functioning. These domains were consistent with the concepts of the common scales, such as the WHOQOL and FACT-G [92,93,94]. The typical manifestation of IBD included diarrhea with blood, fever, abdominal pain and malnutrition. These symptoms are the most frequently occurring, meaning that the domains contribute the most important information to the IBD-specific instruments.

The limitations of this study were as follows: (1) Non-English articles were not enrolled because of language restrictions; thus, the restriction resulted in limited negative evidence for this study; (2) Articles about the original language were used to assess the measurement properties of the included instruments. The translated articles were not used for the assessment of measurement properties; and (3) Some articles about clinical trials may have been excluded in this review, which resulted in a limited ability to examine responsiveness.

Conclusions

This review better guides the use of IBD-specific HRQoL instruments and helps clinicians and researchers choose appropriate IBD instruments. The measurement properties scored low for some IBD-specific HRQoL instruments. Based on the characteristics, measurement properties and applications of the instruments, the IBDQ-32 was the most widely used and had the strongest evidence of being reliable, valid and responsive for adult IBD patients. As a short instrument, the SIBDQ also had good measurement properties and was widely used. The IMPACT-III had good measurement properties and was widely used for paediatric IBD patients. For worldwide use of the new instruments, it is necessary to develop instruments according to the standard procedures (for example, the COSMIN) and make sure their measurement properties had excellent or good ratings. New instruments for IBD should take into account IBD-related symptoms and physical, emotional and social domains.

Abbreviations

- CCQIBD:

-

Cleveland clinic questionnaire for inflammatory bowel disease;

- CD:

-

Crohn’s disease

- CGQL:

-

Cleveland global quality of life

- CLIQ:

-

Crohn’s life impact questionnaire

- COSMIN:

-

Consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments

- CTT:

-

Classical test theory

- CUCQ:

-

Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis questionnaire

- EIBDQ:

-

Edinburgh inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel diseases

- IBDQ-32:

-

32-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- IBDQ-36:

-

36-item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- IBDQ-9:

-

9-Item inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- IMPACT:

-

Quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease

- IMPACT-II:

-

Quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease II

- IMPACT-III:

-

Quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease III

- IRT:

-

Item response theory

- PIBDQL:

-

Padova inflammatory bowel disease quality of life

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- RFIPC:

-

Rating form of IBD patient concerns

- SHS:

-

Short Health Scale

- SIBDQ:

-

Short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- UC:

-

Ulcerative colitis

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

References

Saxena S, Orley J. Quality of life assessment: the World Health Organization perspective. European psychiatry. 1997;12:263s–6s.

Power M, Bullinger M, Harper A. The World Health Organization WHOQOL-100: tests of the universality of quality of life in 15 different cultural groups worldwide. Health Psychol. 1999;18:495–505.

Munkholm P, Pedersen N. Evaluation of quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. In: In: Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: From Epidemiology and Immunobiology to a Rational Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approach.

Veríssimo R. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. In: In: Inflammatory Bowel Disease - Advances in Pathogenesis and Management.

Irvine EJ. Quality of life of patients with ulcerative colitis: past, present, and future. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:554–65.

Wexner SD, Frattini JC: Quality of life in Crohn's disease. In: Handbook of Disease Burdens and Quality of Life Measures.

Pallis AG, Mouzas IA. Instruments for quality of life assessment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:682–8.

Alrubaiy L, Rikaby I, Dodds P, Hutchings HA, Williams JG. Systematic review of health-related quality of life measures for inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:284–92.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmulling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H. Gastrointestinal quality of life index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg. 1995;82:216–22.

Kotecha D, Ahmed A, Calvert M, Lencioni M, Terwee CB, Lane DA. Patient-reported outcomes for quality of life assessment in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of measurement properties. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165790.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–45.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–49.

Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RW, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:651–7.

Alrubaiy L, Hutchings HA, Williams JG. Protocol for a prospective multicentre cohort study to develop and validate two new outcome measures for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003192.

Rauchensteiner S, Miltenburger C, Schaefer M. PGI25 Development and validation of patient reported outcomes measurement scales for Crohn's disease: the inflammatory bowel disease impact and symptom scales (IBDIMSYS). Value Health. 2007;10:A359.

Higgins PD, Harding G, Patrick DL, Revicki DA, Globe G, Viswanathan HN, Trease S, Fitzgerald K, Borie DC, Leidy NK. Tu1124 Development of the Crohn's Disease Patient-Reported Outcomes (CD-PRO) Questionnaire. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S-768. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(13)62840-1.

Higgins PD, Harding G, Patrick DL, Revicki DA, Globe G, Viswanathan HN, Trease S, Fitzgerald K, Borie DC, Leidy NK. Tu1123 Development of the Ulcerative Colitis Patient-Reported Outcomes (UC-PRO) Questionnaire. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:S-768. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(13)62839-5.

Griffiths AM, Nicholas D, Smith C, Munk M, Stephens D, Durno C, Sherman PM. Development of a quality-of-life index for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: dealing with differences related to age and IBD type. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:S46–52.

Loonen HJ, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF, de Haan RJ, Bouquet J, Derkx BHF. Measuring quality of life in children with inflammatory bowel disease: the impact-II (NL). Qual Life Res. 2002;11:47–56.

Ogden CA, Abbott J, Aggett P, Derkx BH, Maity S, Thomas AG. Pilot evaluation of an instrument to measure quality of life in British children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:117–20.

Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine E, Singer J, Williams N, Goodacre R, Tompkins C. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804–10.

Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571–8.

Love JR, Irvine EJ, Fedorak RN. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:15–9.

Alcalá MJ, Casellas F, Fontanet G, Prieto L, Malagelada J. Shortened questionnaire on quality of life for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:383–91.

Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Patrick DL. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701–12.

Farmer RG, Easley KA, Farmer JM. Quality of life assessment by patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cleve Clin J Med. 1992;59:35–42.

Martin A, Leone L, Fries W, Naccarato R. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1995;27:450–4.

Fazio VW, O'riordain MG, Lavery IC, Church JM, Lau P, Strong SA, Hull T. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;230:575–84.

Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Tysk C, Blomberg B, Almer S, Ström M. The short health scale: a valid measure of subjective health in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;41:1196–203.

Smith GD, Watson R, Palmer KR. Inflammatory bowel disease: developing a short disease specific scale to measure health related quality of life. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39:583–90.

Alrubaiy L, Cheung WY, Dodds P, Hutchings HA, Russell IT, Watkins A, Williams JG. Development of a short questionnaire to assess the quality of life in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:66–76.

Wilburn J, McKenna SP, Twiss J, Kemp K, Campbell S. Assessing quality of life in Crohn's disease: development and validation of the Crohn's life impact questionnaire (CLIQ). Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2279–88.

Otley A, Smith C, Nicholas D, Munk M, Avolio J, Sherman PM, Griffiths AM. The IMPACT questionnaire: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:557–63.

Loonen HJ, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF, Koopman HM, Derkx HHF. Quality of life in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease measured by a generic and a disease-specific questionnaire. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:348–54.

Ogden CA, Akobeng AK, Abbott J, Aggett P, Sood MR, Thomas AG. Validation of an instrument to measure quality of life in British children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:280–6.

Irvine EJ. Quality of life-measurement in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:36–9.

Irvine EJ, Feagan BG, Wong CJ. Does self-administration of a quality of life index for inflammatory bowel disease change the results? J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1177–85.

Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Moum B, Bernklev T. Worries and concerns among inflammatory bowel disease patients followed prospectively over one year. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:492034.

Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Barton JR, Welfare MR. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire is reliable and responsive to clinically important change in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2921–8.

Rose M, Fliege H, Hildebrandt M, Körber J, Arck P, Dignass A, Klapp B. Validation of the new German translation version of the "short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire" (SIBDQ). Z Gastroenterol. 2000;38:277–86.

Lam MY, Lee H, Bright R, Korzenik JR, Sands BE. Validation of interactive voice response system administration of the short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:599–607.

López-Vivancos J, Casellas F, Badia X, Vilaseca J, Malagelada JR. Validation of the Spanish version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire on ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Digestion. 1999;60:274–80.

Samsamikor M, Daryani NE, Asl PR, Hekmatdoost A. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized, double-blind. Placebo-controlled Pilot Study Arch Med Res. 2015;46:280–5.

Jelsness-Jørgensen L-P, Bernklev T, Moum B. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: translation, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change of the Norwegian version of the short health scale (SHS). Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1671–6.

McDermott E, Keegan D, Byrne K, Doherty GA, Mulcahy HE. The short health scale: a valid and reliable measure of health related quality of life in English speaking inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohn's Colitis. 2013;7:616–21.

Stjernman H, Grännö C, Järnerot G, Ockander L, Tysk C, Blomberg B, Ström M, Hjortswang H. Short health scale: a valid, reliable, and responsive instrument for subjective health assessment in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:47–52.

Otley AR, Griffiths AM, Hale S, Kugathasan S, Pfefferkorn M, Mezoff A, Rosh J, Tolia V, Markowitz J, Mack D. Health-related quality of life in the first year after a diagnosis of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:684–91.

Perrin JM, Kuhlthau K, Chughtai A, Romm D, Kirschner BS, Ferry GD, Cohen SA, Gold BD, Heyman MB, Baldassano RN. Measuring quality of life in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: psychometric and clinical characteristics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:164–71.

Haapamäki J, Roine RP, Sintonen H, Kolho KL. Health-related quality of life in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease related to disease activity. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:832–7.

Otley AR, Xu S, Yan S, Olson A, Liu G, Griffiths AM. IMPACT-III is a valid, reliable and responsive measure of health-related quality of life in pediatric Crohn's disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:S49.

Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Disease activity, behavioral dysfunction, and health-related quality of life in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1581–6.

Abdovic S, Mocic Pavic A, Milosevic M, Persic M, Senecic-Cala I, Kolacek S. The IMPACT-III (HR) questionnaire: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in Croatian children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn's Colitis. 2013;7:908–15.

Werner H, Landolt MA, Buehr P, Koller R, Nydegger A, Spalinger J, Heyland K, Schibli S, Braegger CP. Validation of the IMPACT-III quality of life questionnaire in Swiss children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:641–8.

W-y C, Garratt AM, Russell IT, Williams JG. The UK IBDQ- a British version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: development and validation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:297–306.

Han SW, McColl E, Steen N, Barton JR, Welfare MR. The inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a valid and reliable measure in ulcerative colitis patients in the north east of England. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:961–6.

Russel MG, Pastoor CJ, Brandon S, Rijken J, Engels L, Van der Heijde D, Stockbrügger RW. Validation of the Dutch translation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ): a health-related quality of life questionnaire in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 1997;58:282–8.

Pontes RMA, Miszputen SJ, Ferreira-Filho OF, Miranda C, Ferraz MB. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: translation to Portuguese language and validation of the "inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire"(IBDQ). Arq Gastroenterol. 2004;41:137–43.

Vlachonikolis IG, Pallis AG, Mouzas IA. Improved validation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire and development of a short form in Greek patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1802–12.

Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Tysk C, Blomberg B, Almer S, Ström M. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire in Swedish patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:77–85.

Bernklev T, Moum B, Moum T. Inflammatory bowel south-eastern Norway Group of G. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: translation, data quality, scaling assumptions, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change of the Norwegian version of IBDQ. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1164.

Hashimoto H, Green J, Iwao Y, Sakurai T, Hibi T, Fukuhara S. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Japanese version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1138–43.

Hauser W, Dietz N, Grandt D, Steder-Neukamm U, Janke KH, Stein U, Stallmach A. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire IBDQ-D, German version, for patients with ileal pouch anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie. 2004;42:131–40.

Ren WH, Lai M, Chen Y, Irvine EJ, Zhou YX. Validation of the mainland Chinese version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ) for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:903–10.

Leong RWL, Lee YT, Ching JYL, Sung JJY. Quality of life in Chinese patients with inflammatory bowel disease: validation of the Chinese translation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:711–8.

Kim WH, Cho YS, Yoo HM, Park IS, Park EC, Lim JG. Quality of life in Korean patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease and intestinal Behcet's disease. Int J Color Dis. 1999;14:52–7.

Abdul-Baki H, ElHajj I, El-Zahabi L, Azar C, Aoun E, Zantout H, Nasreddine W, Ayyach B, Mourad FH, Soweid A. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Lebanon. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;13:475–80.

Oliveira S, Zaltman C, Elia C, Vargens R, Leal A, Barros R, Fogaça H. Quality-of-life measurement in patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving social support. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:470–4.

Ciccocioppo R, Klersy C, Russo ML, Valli M, Boccaccio V, Imbesi V, Ardizzone S, Porro GB, Corazza GR. Validation of the Italian translation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:535–41.

Maleki I, Taghvaei T, Barzin M, Amin K, Khalilian A. Validation of the Persian version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ) in ulcerative colitis patients. Caspian J Intern Med. 2015;6:20–4.

Kennedy AP, Nelson E, Reeves D, Richardson G, Roberts C, Robinson A, Rogers AE, Sculpher M, Thompson DG. A randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness and cost of a patient orientated self management approach to chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:1639–45.

Schreiber S, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Kamm MA, Boivin M, Bernstein CN, Staun M, Thomsen OØ, Innes A. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of certolizumab pegol (CDP870) for treatment of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:807–18.

Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–9.

Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, Sutherland LR, Thomson AB, Williams CN, Nilsson L, Persson T. Oral budesonide as maintenance treatment for Crohn's disease: a placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Canadian inflammatory bowel disease study group. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:45–51.

Van Assche G, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, D'Haens G, Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Ternant D, Watier H, Paintaud G, Rutgeerts P. Withdrawal of immunosuppression in Crohn's disease treated with scheduled infliximab maintenance: a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1861–8.

Hjortswang H, Strom M, Almeida RT, Almer S. Evaluation of the RFIPC, a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire, in Swedish patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:1235–40.

Jaghult S, Saboonchi F, Johansson U-B, Wredling R, Kapraali M. Factor structures of the Swedish version of the RFIPC: investigating the validity of measurements of IBD Patients' worries and concerns. Gastroenterology Research. 2010;3:191–200.

Jelsness-Jørgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Torp R, Moum BA. Chronic fatigue is associated with impaired health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:106–14.

Torres EA, Pérez C, Chinea B, Arroyo J, Aponte N, Guzmán A, Magno P, Provenzale D. Evaluation of the rating form for inflammatory bowel diseases patients concerns (RFIPC) spanish translation in Puerto Ricans with IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;118:2643.

Blondel-Kucharski F, Chircop C, Marquis P, Cortot A, Baron F, Gendre J-P, Colombel F. Health-related quality of life in Crohn's disease: a prospective longitudinal study in 231 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2915–20.

Levenstein S, Li Z, Almer S, Barbosa A, Marquis P, Moser G, Sperber A, Toner B, Drossman DA. Cross-cultural variation in disease-related concerns among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1822–30.

Argyriou K, Roma E, Kapsoritakis A, Tsakiridou E, Oikonomou K, Manolakis A, Potamianos S. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: translation, validation, and first implementation of the Greek version. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:6267175.

Casellas F, Alcalá MJ, Prieto L, Miró JR, Malagelada JR. Assessment of the influence of disease activity on the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease using a short questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:457–61.

Casellas F, Arenas JI, Baudet JS, Fabregas S, Garcia N, Gelabert J, Medina C, Ochotorena I, Papo M, Rodrigo L. Impairment of health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a Spanish multicenter study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:488–96.

Scarpa M, Victor CJ, O'Connor BI, Cohen Z, McLeod RS. Validation of an English version of the Padova quality of life instrument to assess quality of life following ileal pouch anal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:416–22.

Somashekar U, Gupta S, Soin A, Nundy S. Functional outcome and quality of life following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis in Indians. Int J Color Dis. 2010;25:967–73.

Lee J, Lee EH, Moon SH. A systematic review of measurement properties of the instruments measuring health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:2985–95.

Lee J, Kim SH, Moon SH, Lee EH. Measurement properties of rheumatoid arthritis-specific quality-of-life questionnaires: systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2779–91.

Heinl D, Prinsen CAC, Sach T, Drucker AM, Ofenloch R, Flohr C, Apfelbacher C. Measurement properties of quality-of-life measurement instruments for infants, children and adolescents with eczema: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:878–89.

Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:S3–9.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Powers JH, Scott JA, Rock EP, Dawisha S, O'Neill R, Kennedy DL. Patient-reported outcomes to support medical product labeling claims: FDA perspective. Value Health. 2007;10:S125–37.

The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1569–85.

WHOQoL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8.

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Min Xu in Hong Kong Baptist University for searching the full texts of the corresponding instruments.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 81774451; 81403296, 81373786), the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Guangdong Province Colleges and Universities (YQ2015041), the Young Talents Foundation of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (QNYC20140101), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2017A030313827) and the Guangdong High Level Universities Program of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine.

Availability of data and materials

All the data are available in the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XLC carried out the design, assessed the measurement properties of the instruments and wrote and modified the manuscript. LHZ assessed the measurement properties of the instruments, wrote and modified the manuscript. YW helped to extract the data and assessed the measurement properties. TWL and XYL helped to extract the characteristics of the studies. ZKH and YH helped to interpret the results. CWM performed the statistical analyses. FBL carried out the design and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Appendix S1 and Appendix S2. (DOC 80 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, XL., Zhong, Lh., Wen, Y. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease-specific health-related quality of life instruments: a systematic review of measurement properties. Health Qual Life Outcomes 15, 177 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0753-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0753-2