Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers and a leading cause of death worldwide. Due to latent liver disease, late diagnosis, and nonresponse to systemic treatments, surgical resection and/or biopsy specimens are still generally considered as the gold standard by clinicians for clinical decision-making until now. Since the conventional tissue biopsy is invasive and contains small tissue samples, it is unable to represent tumor heterogeneity or monitor dynamic tumor progression. Therefore, it is imperative to find a new less invasive or noninvasive diagnostic strategy to detect HCC at an early stage and to monitor HCC recurrence. Over the past years, a new diagnostic concept known as “liquid biopsy” has emerged with substantial attention. Liquid biopsy is noninvasive and allows repeated analyses to monitor tumor recurrence, metastasis or treatment responses in real time. With the advanced development of new molecular techniques, HCC circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) detection have achieved interesting and encouraging results. In this review, we focus on the clinical applications of CTCs and ctDNA as key components of liquid biopsy in HCC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers and a leading cause of death worldwide. There are more than 841,000 patients diagnosed with HCC globally. In China, HCC ranks third in cancer-related mortality [1] as the result of latent liver disease, late diagnosis, and limited treatments. Currently, surgical resection or liver transplantation remains the primary therapy for HCC patients. Unfortunately, most patients at the time of first HCC diagnosis, have already reached an advanced cancer stage, and only approximately 20–30% of the patients are eligible for surgical intervention. Moreover, although the 5-year survival rate of early HCC (BCLC stage A) is high (50–75%), the prognosis of HCC is still limited due to 50–70% recurrence rate after radical surgical resection or ablation [2]. Currently, early detection or monitoring HCC recurrence mainly relies on imageology, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels and tissue biopsy [3]. Nevertheless, imaging and pathological examinations still have their limitations in diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity, while common serum markers display poor diagnostic performance [4]. Therefore, it is critical to find a robust method to detect early HCC and to monitor tumor recurrence.

A new diagnostic concept known as “liquid biopsy” has emerged with substantial attention over the past years [5, 6]. A liquid biopsy collects the sample of body nonsolid biological tissue, such as blood for different analyses. Several other body fluids could also be used for specific liquid biopsy applications, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for central nervous system tumors, saliva for head and neck tumors, pleural fluid for thoracic and metastatic cancers, ascites for abdominal and metastatic cancers, stool for gastrointestinal tract cancers and urine for urinary tract cancers [7]. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) are cornerstones of liquid biopsy. Besides, cell-free microRNA and extracellular RNA, such as exosomes or tumor-educated platelets (TEPS), are also present in a liquid biopsy specimen.

In HCC, the molecular pathogenesis is extremely complex and heterogeneous. Currently, the pathological profile of HCC is obtained from surgical or biopsy specimens. However, a conventional biopsy cannot always be performed routinely due to its invasive nature. The information acquired from a single biopsy provides a limited snapshot of a tumor and always fails to reflect its heterogeneity. However, a liquid biopsy can overcome this weakness, provide the genetic profile of all cancerous lesions (primary and metastatic tumors) as well as offer the opportunity to systematically and dynamically track genomic evolution [8]. Moreover, analysis of therapeutic targets and drug resistance-conferring gene mutations from CTCs and ctDNA released into the circulation contributes to a better understanding and clinical management of drug resistance in cancer patients. To date, excellent progress has been made using liquid biopsy as blood-based biomarkers in HCC. These novel biomarkers are believed to have great potential and could provide more detailed individualized decision-making during HCC management, including early detection, prediction of treatment and prognostic outcome. In this review, we focus on the clinical applications of CTCs and ctDNA as crucial components of the liquid biopsy in the HCC diagnosis, prognosis and therapy.

Main text

The biological basis of liquid biopsy

CTCs

In the 1860s, CTCs were discovered using a microscope to examine the peripheral blood [9]. In brief, CTCs are cancer cells that circulate in the bloodstream after being naturally shed from the original or metastatic tumors, which can lead to a new fatal metastasis and can be vividly described as “seeds” of the tumors (Fig. 1).

CTCs and ctDNA in the peripheral blood. CTCs and ctDNA are the essential elements and are widely believed to be the cornerstones of the liquid biopsy. CTCs are cancer cells that circulate in the bloodstream after being naturally shed from the original or metastatic tumors, they are “seeds” of tumors and can lead to a new fatal metastasis; ctDNA is derived from apoptotic and necrotic tumor cells that release their fragmented DNA into the circulation and contain genetic defects identical to the original tumor cells

The number of CTCs in the blood are very low, which count up to a few hundred per milliliter depending on the available detection/isolation technology and the CTC definition used. To date, many “CTC” definitions exist; the CellSearch definition is considered as the current standard and states that a CTC is a circulating nucleated cell larger than 4 μm, expressing epithelial proteins EpCAM, and cytokeratins 8, 18, and/or 19, while being negative for the leukocyte-specific antigen CD45 [10].

The time of CTCs in the bloodstream is short (half-life: 1–2.4 h [11]), and the detection of CTCs in patient blood months or years after primary tumor resection indicates tumor recurrence or metastasis. Although the capture of CTCs from the whole blood is cumbersome, CTCs offer the opportunity to obtain information at the DNA, RNA and protein levels. However, the clinical application of CTCs remains challenging. The most important difficulty is that the earlier the cancer stage is, the fewer the CTCs. When CTCs enter the circulatory system, they will undergo apoptosis due to loss of adhesion to the extracellular matrix, hemodynamic shear forces, attacks of the body immune system [12] and target drugs. Only less than 0.01% of CTCs released into the circulation survive to produce metastasis [13]. These properties limit the application of CTCs detection in the early cancer diagnosis. Therefore, a detection technique of high sensitivity and specificity is urgently needed to expand the clinical applicability of CTCs.

ctDNA

Regarding ctDNA, cell-free DNA (cfDNA) must be mentioned. cfDNA is released by dying nonmalignant host cells and possibly also is actively secreted by lymphocytes [14]. Tumor DNA can be released from the primary or metastatic tumors, and CTCs into the blood of cancer patients [6]. It is widely accepted that the majority of such ctDNA is derived from apoptotic and necrotic tumor cells that release their fragmented DNA into the circulation [8, 14,15,16]; In principle, ctDNA contains genetic defects identical to the tumor cells they originated from (Fig. 1). However, ctDNA represents only a small fraction of the total cfDNA and is always diluted by larger quantities of DNA from noncancerous origins. Currently, there is no way to isolate ctDNA specifically from other circulating DNAs, and only the detection of tumor-specific mutations on circulating cfDNA indicates the presence of ctDNA [17].

cfDNA is double-stranded DNA existing in plasma or serum, and ctDNA molecules are usually shorter than nonmutant cfDNA molecules [18]. The modal size of ctDNA for many cancers is less than 167 bp, which is the length of DNA wrapping around the chromatosome. Additionally, selecting fragments between 90 and 150 bp improved the detection of ctDNA [19]. Interestingly, cancer patients have much higher levels of normal cfDNA than healthy individuals, which dilutes the ctDNA in particular when tissue-damaging therapies, such as surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, are administered [6]. Additionally, cfDNA has a short half-life between 16 min and 2.5 h [20, 21]. All these factors make ctDNA detection more difficult. Early studies showed that ctDNA possess many cancer-associated molecular characteristics, such as single-nucleotide mutations [22,23,24,25,26], methylation changes [27,28,29,30] and cancer-derived viral sequences [31,32,33], which may allow the discrimination of ctDNA from normal circulating cfDNA and guide the development of detection techniques.

Methodology of liquid biopsy detection in HCC

In recent decades, CTCs and ctDNA have been intensively detected in HCC patients. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the previously demonstrated characteristics of CTCs and ctDNA.

Technology platform for CTCs

In recent years, many different CTC isolation techniques have been developed, which can be generally divided into two groups: physical methods and biological methods. The former mainly depends on the physical properties of CTCs, such as size (filtration-based devices), density (Ficoll centrifugation), electric charge (dielectrophoresis), migratory capacity, and deformability [52]. The latter mainly relies on the antigen-antibody binding by using antibodies against tumor-specific biomarkers, including epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and so on [82]. Above all, EpCAM is the most commonly used antigen in CTC purification because its expression is virtually universal in cells of epithelial origin and is absent in blood cells [83]. Furthermore, the EpCAM-based CellSearch system is still the first and only clinically validated FDA-approved test for capturing and enumerating CTCs. Using anti-EpCAM-coated magnetic beads, CTCs are extracted from the blood, fixed, stained, and manually counted. However, this approach may miss highly metastatic potential tumor cells during the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process, which is characterized by the decreased expression of epithelial markers and the acquisition of mesenchymal features [84].

In summary, multiple different approaches will likely be required to capture CTCs, possibly consisting of the combinations of less specific enrichment steps (physical methods), followed by more specific isolation techniques, including fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), microarray, immune-fluorescence, sequencing, flow cytometry, and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) [85].

However, in liver cancers, only a small percentage (0–20%) of HCC patients were positive for EpCAM [86, 87]. As an alternative to macroscale systems, researchers have turned to emerging microfluidic technology to build promising microscale CTC isolation system since 2007, when a so-called CTC chip was developed to capture rare CTCs [88]. The CTC-chip has advantages, including enhanced interactions between the CTCs, functionalized surface and dynamic flows that prohibit nonspecific binding [89]. In summary, various types of techniques are available to collect and isolate CTCs, which will facilitate future cancer research. Of course, most techniques need to be validated as well.

Technology platform for ctDNA

ctDNA accounts for only a small percentage (sometimes < 0.01%) of the total cfDNA in the peripheral blood. The changes of ctDNA in plasma are quantitative and qualitative. The former refers to the total ctDNA concentrations, and the latter refers to DNA aberrations, such as single nucleotide mutations, copy number variations and methylation changes [85].

In recent years, many methods with high sensitivity and specificity have been developed, including digital PCR [90], BEAMing [21], Safe-SeqS [91], Capp-Seq [92] and TAm-Seq [93], to detect single-nucleotide mutations in ctDNA or whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to establish copy-number changes. In brief, techniques based on the analysis of ctDNA can be mainly divided as targeted or untargeted. The former aims to detect mutations in a set of predefined genes (e.g., KRAS), and the latter aims to screen the genome and discover new genomic aberrations (e.g., WGS), such as those confer resistance to a specific targeted therapy [94].

Currently, both digital PCR (dPCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are the two advanced techniques for detecting DNA aberrations. The dPCR technique has been widely applied to detect targeted DNA aberrations. Although the PCR-based technique has very high sensitivity and, for example, can monitor tumor-associated genetic mutations at frequencies as low as 0.01% [22], this technique can only detect limited numbers of foci. To overcome this issue, the NGS technique is now used to obtain a more comprehensive view of the entire genomic landscape. Approaches involving deep sequencing include Safe-SeqS, Capp-Seq, TAm-Seq and AmpliSeq [95]. With these techniques, the NGS provides information to characterize personalized cancer gene maps and develop personalized medicine.

Prognostic value of CTCs in HCC

CTCs are widely believed to be a significant determinant of metastasis and recurrence in cancers and are not recommended as an independent HCC diagnostic tool [96]. Therefore, CTCs may serve as a potential biomarker for prognosis.

Currently, EpCAM+CTCs have been intensively investigated in HCC, although the knowledge about their clinical relevance in HCC is lagging behind other major tumor types, such as breast cancer, prostate cancer and lung cancer [97]. The overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were significantly shorter in the CTC-positive cohort with HCC [34] and also associated with poor clinical characteristics [40]. However, the definition of CTC positivity is still conflicting. Some researchers defined CTC positivity as “≥1 CTC” or “≥2 CTC”, but others used “≥5 CTC” to analyze results. However, one thing for sure is that the more CTCs are detected, the poorer prognosis the patients will have.

In addition, EpCAM+CTCs may serve as a real-time parameter for monitoring HCC recurrence. A preoperative CTC (7.5 ml) of ≥2 is a novel predictor for tumor recurrence in HCC patients after surgery, especially in patient subgroups with AFP levels of ≤400 ng/mL or low tumor recurrence risk [48]. Nevertheless, only approximately 35% of HCC cases express EpCAM, limiting the clinical application of EpCAM+CTCs in predicting prognosis. Some other methods have tried to overcome this dilemma. For instance, detection of EpCAM+CTCs with co-existing CD4 + CD25 + Foxp3+ Treg cells indicated HCC recurrence. Zhou et al. [98] discovered that patients with high CTC/Treg levels showed a significantly higher risk of developing postoperative HCC recurrence than those with low CTC/Treg levels (66.7% vs. 10.3%, P < 0.001). Apart from this attempt, other subtypes of CTCs for early prediction of HCC recurrence were also explored. Zhong et al. [99] found that of the 62 HCC patients, mesenchymal CTCs and mixed CTCs in the recurrence group were significantly higher than in the nonrecurrence group, and mesenchymal CTC positivity (HR = 3.453, P = 0.007) was an independent risk factor for early recurrence. A similar study [35] also found that CTC count ≥16 and mesenchymal-CTC percentage ≥ 2% before resection were significantly associated with early recurrence, multi-intrahepatic recurrence, and lung metastasis. Altogether, different markers and combinations in CTCs can serve as a tool for predicting HCC recurrence and prognosis, but those markers may not be specific to HCC and limit the use of CTCs in early diagnosis in some way.

Diagnostic value of ctDNA in HCC

In general, ctDNA mainly shows great diagnostic value in HCC. ctDNA is superior to that of previously described plasma biomarkers in terms of higher sensitivity and better clinical correlation.

In recent years, the “methylation pattern” of ctDNA has been the most intensively investigated hotspot [13]. Since methylation changes in ctDNA occur early in tumorigenesis and are potentially reversible, changes in methylation may offer the best hope for early cancer detection. Furthermore, methylation patterns are unique to each cell type and are highly stable under physiologic or pathologic conditions [100]. Therefore, the recognition of different methylation patterns may have the potential to serve as discriminatory tools for the detection and diagnosis of HCC. Wong and colleagues [81] detected for the first time that concurrent p15 and p16 methylation was positive in the plasma/serum of 92% (11 of 12) of HCC patients. Following this study, many researchers investigated the cfDNA methylation profile in HCC patients. For instance, Ras association domain family 1A (RASSF1A) promoter hypermethylation [77] was detected in 90% of the HCC group and could differentiate HCC patients from healthy controls and chronic HCV infection alone with an overall predictive accuracy of 77.5 and 72.5%, respectively. Therefore, aberrant promoter methylation in ctDNA could be evaluated as a screening tool for HCC patients, especially for small HCC among high-risk populations at an early stage.

Moreover, several hot methylated genes were combined to diagnose HCC. For example, p16, p15 and RASSF1A were explored in the serum of 50 HCC patients and provided an overall predictive accuracy of 89% with sensitivity and specificity of 84 and 94%, respectively [73]. A panel of four genes (APC, GSTP1, RASSF1A, and SFRP1, [68]) could discriminate HCC from normal controls with 92.7% sensitivity and 81.9% specificity. Additionally, three abnormally methylated genes (APC, COX2, RASSF1A) and one miRNA (miR-203) were combined to establish a predictive model by which nearly 75% of patients, who could not be diagnosed with AFP at 20 ng/mL, were detected [56]. Recently, Xu et al. [101] identified an HCC-specific methylation marker panel including ten markers and constructed a diagnostic prediction model that showed high diagnostic specificity (90.5%) and sensitivity (83.3%) superior to AFP (AUC 0.696 vs. 0.816), differentiating HCC patients from those with liver diseases or healthy controls. Interestingly, normal controls with positive detection likely to had etiological risk factors of HCC such as HBV infection and/or alcohol drinking history. In conclusion, hypermethylation in promoter regions is now recognized as an important early event in carcinogenesis. The combinations of different methylated tumor suppressor genes were absent or very low in normal tissues DNA. Therefore, detection of those DNA is specific to HCC and can diagnose HCC with high specificity and sensitivity.

Currently, the most commonly used serum marker AFP has limited diagnostic value because of low sensitivity of only 50% in HCC. cfDNA levels could discriminate HCC and HCV carriers at the optimal cutoff value of 73.0 ng/ml with a sensitivity of 69.2% and a specificity of 93.3% [76]. In addition, the combined AFP and cfDNA detection can improve HCC diagnosis. A study [102] showed an elevated diagnostic value with 95.1% sensitivity and 94.4% specificity in discriminating HCC from normal controls when using the combined detection of cfDNA and AFP. A similar study [103] found that the sensitivity of the combined detection of cfDNA with one marker (AFP or AFU) and cfDNA with two markers (AFP and AFU) was 71.8, 87.2 and 89.7% vs. 56.4, 53.8 and 66.7% for cfDNA, AFP and AFU when used alone, respectively. In AFP-negative HCC, the levels of plasma hTERT DNA in HCC patients with AFP ≤ 20 ng/ml were significantly higher than in HBV patients [69], indicating that hTERT DNA may serve as a novel complementary tool for AFP in the screening and detection of HCC. In a word, quantitative analysis of cfDNA is sensitive and feasible, and the diagnostic value of cfDNA is superior to AFP or AFU. Combined detection of cfDNA with AFP or AFU or both could improve diagnostic sensitivity of HCC. Furthermore, it is intriguing to imagine quantitation of cfDNA together with somatic mutation analysis to screen malignancy in the further. However, the definition of elevated cfDNA level is hard to decide and the optimal cut-off point is controversial in different researches because of various detection methods used.

Apart from its association with the malignancy, cfDNA could also be used as a potential biomarker to stratify liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Hardy, T. et al. [104] found that plasma DNA methylation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) gene promoter increased with fibrosis severity and could be used as an independent predictor of fibrosis severity in NAFLD.

Prognostic value of ctDNA in HCC

Except for early diagnosis, ctDNA also plays a vital role in HCC prognosis. For untargeted ctDNA, the levels of cfDNA are always negatively associated with DFS and OS [105, 106] and may serve as an independent prognostic factor for HCC recurrence and extrahepatic metastasis [107].

Targeted ctDNA detection can also reflect intratumoral heterogeneity and predict poor prognosis. Hot spot mutants, such as TP53, CTNNB1, and TERT, were the most preferred targets for the detection of ctDNA aberrations. Using droplet digital PCR, 27 of 48 HCC patients (56.3%) were found to have at least one kind of circulating mutant, with the mutant allele frequency ranging from 0.33 to 23.7% [58], indicating intra-tumoral heterogeneity in HCC. Another study used the MiSeq™ system to detect the same mutations, finding that ctDNA with mutations could be detected more easily in patients who suffered vascular invasion (P = 0.041) and predicted a shorter DFS time (P < 0.001, [57]). In addition, allelic imbalance (AI) on chromosome 8p at D8S264 in circulating plasma DNA was closely associated with the 3-year DFS (P = 0.014), and combined detection with cfDNA levels was independently associated with DFS (P = 0.018) and OS (P = 0.002) of patients with HCC [75]. In general, continuous detection of tumor-associated mutations in ctDNA can overcome the limitations of tumor heterogeneity and predict prognosis of HCC. However, there is still a problem because the circulating mutants are not all derived from tumor cells since germline mutation might also be detected in plasma. Therefore, it is necessary to screen corresponding tumor samples to identify their origins.

Tumor monitoring and therapeutic evaluation

Surgical resection remains the primary treatment for HCC. ctDNA and CTCs are also used to assess the effect of surgical resection and monitor tumor burden. For instance, Wong et al. [79] found that the median p16INK4a methylation induced in plasma and buffy coat concordantly decreased 12- and 15-fold after surgical resection, respectively; Fan and his colleagues [108] used an orthotopic model by in vivo flow cytometry to detect CTCs in HCC, finding that the number of CTCs and early metastases decreased significantly after the resection, concluding that the resection prominently restricted hematogenous disseminating and distant metastases.

Subtypes of CTCs may associate with therapeutic response and could serve as a supplement for molecular subtype in HCC. Nel et al [109] investigated 11 patients with different therapies (watch and wait: 3; selective internal radiation therapy: 5; transarterial chemoembolization (TACE): 1; resection: 1; Nexavar: 1), detected a remarkable variation of CTCs with epithelial, mesenchymal, liver-specific, and mixed characteristics and found that different subgroups varied significantly among patients. Importantly, these CTC subgroups were associated with the therapeutic outcomes, and an increase in epithelial cells was associated with a worse treatment outcome in HCC patients. In addition, pERK+/pAkt- CTCs were more sensitive to sorafenib and remained an independent factor associated with a good prognosis (hazard ratio = 9.389, P < 0.01) in HCC patients [110]. Moreover, in vitro released CTCs were also evaluated for their sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs. Zhang at el [38] used a microfluidic chip to isolate and release viable CTCs, and the CTCs-treated sorafenib (5 samples) or oxaliplatin (5 samples) formed a significantly less number of spheroids compared to the control. To conclude, individual profiling of CTCs may have distinct clinical implications, which might help to predict outcome and potentially to select the appropriate treatment.

Importantly, somatic mutation frequency of ctDNA reflected clinical dynamics corresponding to sequential therapy and might provide a possible solution for monitoring tumor burden and prognosis. Cai et al. [111] monitored an HCC patient during the course of comprehensive therapy and observed an increased circulating level of 8 somatic mutations even before imaging diagnosis and the increase of AFP levels after the first TACE treatment. In this process, 1 nonsynonymous somatic mutation (HCKp. V174 M) was identified after the first TACE treatment and then became undetectable after the second surgery, while it sharply increased during the second recurrence. Therefore, ctDNA could track the change of different mutants and therapeutic responses in real-time longitudinal monitoring.

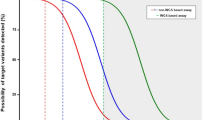

Moreover, somatic mutations detected in ctDNA can guide therapy. Ikeda et al. [54] evaluated 14 patients with advanced HCC. A patient with a CDKN2A-inactivating and a CTNNB1-activating mutation received palbociclib (CDK4/6 inhibitor) and celecoxib (COX-2/Wnt inhibitor) treatment and found low levels of AFP at baseline at 2 months. Another patient with a PTEN-inactivating and a MET-activating mutation received sirolimus (mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitor) and cabozantinib (MET inhibitor) and found AFP declined by 63% (8320 to 3045 ng/mL). In conclusion, ctDNA derived from noninvasive blood tests can provide exploitable genomic profiles in patients with HCC and guide therapy in some ways (Fig. 2).

Phantom drawing of clinical applications of liquid biopsy in HCC patients. Monitoring the response and relapse of HCC patients using liquid biopsy, the levels of ctDNA and CTCs correlate well with HCC progression as well as various therapies, including surgical resection, TACE, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and targeted molecular therapy

Challenges and perspectives

In general, liquid biopsy is an exciting method that is noninvasive, overcomes tumor heterogeneity and can monitor tumor progression, recurrence or therapeutic response in real time. There is also an ongoing clinical trial (NCT02973204) from the US National Laboratory of Medicine (NIH) for CTCs and ctDNA in HCC, aiming at predicting which patients require special monitoring and individualized therapy and exploring the value of these tests in supporting clinical decision-making. However, there are challenges that researchers face in translating liquid biopsy from bench to bedside that still stand in the way.

First, the biological basis of CTCs or ctDNA is controversial; for example, the exact mechanisms by which ctDNA is released into the blood remains to be clarified. Apoptosis and necrosis are the most discussed origins of cfDNA [112]. Autophagy and hypoxia might account for ctDNA release. Malignant cells could activate autophagy as a survival mechanism, and autophagic activity regulates apoptosis; as a result, ctDNA is released [113]. Exposures to intermittent hypoxia (IH) could increase the shedding of ctDNA into the circulation [114]. Therefore, it is important to gain a better understanding of the biological characteristics of the liquid biopsy.

The descriptions of CTCs and ctDNA in this review are mainly focused on HCC. However, many other types of cancers may detect the same mutations in genes, such as TP53, KRAS, or BRAF. Cancer-associated mutations occur with increasing age, raising a problem that cannot be neglected: how could cfDNA be tissue-specific? The epigenetic biomarkers of cfDNA may answer this question [115]. DNA methylation is the most favored epigenetic modification whose profile is highly tissue-specific and shows the potential to determine the tissue origin of cfDNA [116,117,118,119]. In addition, the nucleosome occupancy and the ending pattern of cfDNA molecules also reflect the original tissues. By deep sequencing cfDNA, Snyder et al. generated maps of genome-wide in vivo nucleosome occupancy and found nucleosome spacing patterns, providing the information of the tissues of origin for cfDNA [120]. There were millions of plasma ctDNA end coordinates across the genome, and HCC-associated ctDNA had preferred end signatures different from other cfDNA [121], making it possible to trace the origin of ctDNA.

Moreover, liquid biopsy, especially ctDNA, shows considerable potential in classifying molecular subtyping of certain malignancies. Plasma ctDNA genotyping can classify transcriptionally defined tumor subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Biopsy-free plasma genotyping of ctDNA in 41 DLBCL patients was highly consistent with tumor tissue biopsy classification (88%) [122], which may facilitate individualized therapy. Martínez-Ricarte F et al developed a sequencing platform to simultaneously and rapidly genotype seven genes (IDH1, IDH2, TP53, TERT, ATRX, H3F3A, and HIST1H3B) in CSF ctDNA, allowing the subclassification of diffuse gliomas, the most common primary tumor of the brain, having different subtypes with diverse prognoses [123].

Nevertheless, liquid biopsy has its own limitations. The techniques of collecting “liquid”, and the isolation, enrichment or detection of CTCs and ctDNA must be standardized. Most of the current studies used different technologies or assays to detect CTCs or ctDNA, resulting in diverse sensitivity and specificity. Although ctDNA has high specificity in diagnosis, a multi-marker analysis may offer a more comprehensive insight into cancer specificity [55, 56, 101]. In addition, more multicenter, larger and longer-term studies are urgently needed for the implementation of the liquid biopsies clinically, including clinical trials. Currently, most of the data gathered have been within proof-of-concept studies and lack of credibility. Altogether, the liquid biopsy is a critical part of precise medicine, and is believed will become a clinical reality in near future.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- AFU:

-

α-L-fucosidase

- AI:

-

Allelic imbalance

- APC:

-

Adenomatosis Polyposis Coli

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- BEAMing:

-

Bead, Emulsion, Amplification, Magnetic

- Capp-Seq:

-

Cancer personalized profiling by deep sequencing

- CDK6:

-

Cyclin-dependent kinase 6

- cfDNA:

-

Cell-free DNA

- COX2:

-

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CTCs:

-

Circulating tumor cells

- ctDNA:

-

Circulating tumor DNA

- CTNNB1:

-

Catenin beta 1

- DFS:

-

Disease-free survival

- dPCR:

-

Digital PCR

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- EMT:

-

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- EpCAM:

-

Epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- GSTP1:

-

Glutathione S-transferase pi 1

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B Virus

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C Virus

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- hTERT:

-

Human telomerase reverse transcriptase

- KRAS:

-

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- miRNA:

-

MicroRNA

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- CDKN2A(p16INK4a):

-

Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- PTEN:

-

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- RASSF1A:

-

Ras association domain family 1A

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- Safe-SeqS:

-

Safe-Sequencing System

- SFRP1:

-

Secreted frizzled related protein 1

- TACE:

-

Transarterial chemoembolization

- TAm-Seq:

-

Tagged-amplicon deep sequencing

- TEPS:

-

Tumor-educated blood platelets

- TERT:

-

Telomerase reverse transcriptase

- TP53:

-

Tumor protein p53

- WGS:

-

Whole-genome sequencing

References

Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–32.

European Association For The Study Of The L, European Organisation For R, Treatment Of C. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56(4):908–43.

Colombo F, Baldan F, Mazzucchelli S, Martin-Padura I, Marighetti P, Cattaneo A, et al. Evidence of distinct tumour-propagating cell populations with different properties in primary human hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21369.

Zhou L, Liu J, Luo F. Serum tumor markers for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(8):1175–81.

Diaz LA Jr, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsies: genotyping circulating tumor DNA. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):579–86.

Alix-Panabieres C, Pantel K. Clinical applications of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA as liquid biopsy. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(5):479–91.

Corcoran RB, Chabner BA. Application of cell-free DNA analysis to Cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(18):1754–65.

Crowley E, Di Nicolantonio F, Loupakis F, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsy: monitoring cancer-genetics in the blood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(8):472–84.

Ashworth TR. A case of cancer in which cells similar to those in the tumours were seen in the blood after death. Aust Med J. 1869;14:146–9.

van de Stolpe A, Pantel K, Sleijfer S, Terstappen LW, den Toonder JM. Circulating tumor cell isolation and diagnostics: toward routine clinical use. Cancer Res. 2011;71(18):5955–60.

Meng S, Tripathy D, Frenkel EP, Shete S, Naftalis EZ, Huth JF, et al. Circulating tumor cells in patients with breast cancer dormancy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(24):8152–62.

Strilic B, Offermanns S. Intravascular survival and extravasation of tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(3):282–93.

Okajima W, Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, Miyamae M, Ohashi T, Imamura T, et al. Liquid biopsy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: circulating tumor cells and cell-free nucleic acids. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(31):5650–68.

van der Vaart M, Pretorius PJ. The origin of circulating free DNA. Clin Chem. 2007;53(12):2215.

Stroun M, Lyautey J, Lederrey C, Olson-Sand A, Anker P. About the possible origin and mechanism of circulating DNA apoptosis and active DNA release. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;313(1–2):139–42.

Anker P, Stroun M, Maurice PA. Spontaneous release of DNA by human blood lymphocytes as shown in an in vitro system. Cancer Res. 1975;35(9):2375–82.

Pantel K, Alix-Panabieres C. Real-time liquid biopsy in cancer patients: fact or fiction? Cancer Res. 2013;73(21):6384–8.

Underhill HR, Kitzman JO, Hellwig S, Welker NC, Daza R, Baker DN, et al. Fragment length of circulating tumor DNA. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(7):e1006162.

Mouliere F, Chandrananda D, Piskorz AM, Moore EK, Morris J, Ahlborn LB, et al. Enhanced detection of circulating tumor DNA by fragment size analysis. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(466).

Lo YM, Zhang J, Leung TN, Lau TK, Chang AM, Hjelm NM. Rapid clearance of fetal DNA from maternal plasma. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(1):218–24.

Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, Romans K, Goodman S, Li M, et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med. 2008;14(9):985–90.

Chan KC, Jiang P, Zheng YW, Liao GJ, Sun H, Wong J, et al. Cancer genome scanning in plasma: detection of tumor-associated copy number aberrations, single-nucleotide variants, and tumoral heterogeneity by massively parallel sequencing. Clin Chem. 2013;59(1):211–24.

Yung TK, Chan KC, Mok TS, Tong J, To KF, Lo YM. Single-molecule detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in plasma by microfluidics digital PCR in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(6):2076–84.

Diehl F, Li M, Dressman D, He Y, Shen D, Szabo S, et al. Detection and quantification of mutations in the plasma of patients with colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(45):16368–73.

Qiu M, Wang J, Xu Y, Ding X, Li M, Jiang F, et al. Circulating tumor DNA is effective for the detection of EGFR mutation in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24(1):206–12.

Freidin MB, Freydina DV, Leung M, Montero Fernandez A, Nicholson AG, Lim E. Circulating tumor DNA outperforms circulating tumor cells for KRAS mutation detection in thoracic malignancies. Clin Chem. 2015;61(10):1299–304.

Wong IH, Lo YM, Zhang J, Liew CT, Ng MH, Wong N, et al. Detection of aberrant p16 methylation in the plasma and serum of liver cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1999;59(1):71–3.

Chan KC, Lai PB, Mok TS, Chan HL, Ding C, Yeung SW, et al. Quantitative analysis of circulating methylated DNA as a biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chem. 2008;54(9):1528–36.

Chan KC, Jiang P, Chan CW, Sun K, Wong J, Hui EP, et al. Noninvasive detection of cancer-associated genome-wide hypomethylation and copy number aberrations by plasma DNA bisulfite sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(47):18761–8.

Balgkouranidou I, Chimonidou M, Milaki G, Tsarouxa EG, Kakolyris S, Welch DR, et al. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor-1 promoter methylation in cell-free DNA provides prognostic information in non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(8):2054–62.

Lo YM, Chan LY, Lo KW, Leung SF, Zhang J, Chan AT, et al. Quantitative analysis of cell-free Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59(6):1188–91.

Chan KC, Hung EC, Woo JK, Chan PK, Leung SF, Lai FP, et al. Early detection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA analysis in a surveillance program. Cancer. 2013;119(10):1838–44.

Campitelli M, Jeannot E, Peter M, Lappartient E, Saada S, de la Rochefordiere A, et al. Human papillomavirus mutational insertion: specific marker of circulating tumor DNA in cervical cancer patients. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43393.

Yu JJ, Xiao W, Dong SL, Liang HF, Zhang ZW, Zhang BX, et al. Effect of surgical liver resection on circulating tumor cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):835.

Qi LN, Xiang BD, Wu FX, Ye JZ, Zhong JH. Circulating tumor cells undergoing EMT provide a metric for diagnosis and prognosis of patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2018;78(16):4731–44.

von Felden J, Schulze K, Krech T, Ewald F, Nashan B, Pantel K, et al. Circulating tumor cells as liquid biomarker for high HCC recurrence risk after curative liver resection. Oncotarget. 2017;8(52):89978–87.

Ogle LF, Orr JG, Willoughby CE, Hutton C, McPherson S, Plummer R, et al. Imagestream detection and characterisation of circulating tumour cells - a liquid biopsy for hepatocellular carcinoma? J Hepatol. 2016;65(2):305–13.

Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zhang J, Sun B, Zheng L, Li J, et al. Microfluidic chip for isolation of viable circulating tumor cells of hepatocellular carcinoma for their culture and drug sensitivity assay. Cancer Biol Ther. 2016;17(11):1177–87.

Wang S, Zhang C, Wang G, Cheng B, Wang Y, Chen F, et al. Aptamer-mediated transparent-biocompatible nanostructured surfaces for Hepotocellular circulating tumor cells enrichment. Theranostics. 2016;6(11):1877–86.

Kelley RK, Magbanua MJ, Butler TM, Collisson EA, Hwang J, Sidiropoulos N, et al. Circulating tumor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma: a pilot study of detection, enumeration, and next-generation sequencing in cases and controls. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:206.

Choi GH, Kim GI, Yoo JE, Na DC, Han DH, Roh YH, et al. Increased expression of circulating Cancer stem cell markers during the perioperative period predicts early recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(Suppl 3):S1444–52.

Bahnassy AA, Zekri AR, El-Bastawisy A, Fawzy A, Shetta M, Hussein N, et al. Circulating tumor and cancer stem cells in hepatitis C virus-associated liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(48):18240–8.

Guo W, Yang XR, Sun YF, Shen MN, Ma XL, Wu J, et al. Clinical significance of EpCAM mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma by an optimized negative enrichment and qRT-PCR-based platform. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(18):4794–805.

Morris KL, Tugwood JD, Khoja L, Lancashire M, Sloane R, Burt D, et al. Circulating biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74(2):323–32.

Fang ZT, Zhang W, Wang GZ, Zhou B, Yang GW, Qu XD, et al. Circulating tumor cells in the central and peripheral venous compartment - assessing hematogenous dissemination after transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1311–8.

Li YM, Xu SC, Li J, Han KQ, Pi HF, Zheng L, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers expressed in circulating tumor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with different stages of disease. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e831.

Schulze K, Gasch C, Staufer K, Nashan B, Lohse AW, Pantel K, et al. Presence of EpCAM-positive circulating tumor cells as biomarker for systemic disease strongly correlates to survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(9):2165–71.

Sun YF, Xu Y, Yang XR, Guo W, Zhang X, Qiu SJ, et al. Circulating stem cell-like epithelial cell adhesion molecule-positive tumor cells indicate poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1458–68.

Liu S, Li N, Yu X, Xiao X, Cheng K, Hu J, et al. Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 by hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells and circulating tumor cells. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):1031–41 e10.

Xu W, Cao L, Chen L, Li J, Zhang XF, Qian HH, et al. Isolation of circulating tumor cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel cell separation strategy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(11):3783–93.

Fan ST, Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN, Yu WC, Wong J. Prediction of posthepatectomy recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma by circulating cancer stem cells: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2011;254(4):569–76.

Vona G, Estepa L, Beroud C, Damotte D, Capron F, Nalpas B, et al. Impact of cytomorphological detection of circulating tumor cells in patients with liver cancer. Hepatology. 2004;39(3):792–7.

Mou DC, Cai SL, Peng JR, Wang Y, Chen HS, Pang XW, et al. Evaluation of MAGE-1 and MAGE-3 as tumour-specific markers to detect blood dissemination of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(1):110–6.

Ikeda S, Tsigelny IF, Skjevik AA, Kono Y, Mendler M, Kuo A, et al. Next-generation sequencing of circulating tumor DNA reveals frequent alterations in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2018;23(5):586–93.

Wu HC, Yang HI, Wang Q, Chen CJ, Santella RM. Plasma DNA methylation marker and hepatocellular carcinoma risk prediction model for the general population. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38(10):1021–8.

Lu CY, Chen SY, Peng HL, Kan PY, Chang WC, Yen CJ. Cell-free methylation markers with diagnostic and prognostic potential in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(4):6406–18.

Liao W, Yang H, Xu H, Wang Y, Ge P, Ren J, et al. Noninvasive detection of tumor-associated mutations from circulating cell-free DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma patients by targeted deep sequencing. Oncotarget. 2016;7(26):40481–90.

Huang A, Zhang X, Zhou SL, Cao Y, Huang XW, Fan J, et al. Detecting circulating tumor DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma patients using droplet digital PCR is feasible and reflects Intratumoral heterogeneity. J Cancer. 2016;7(13):1907–14.

Kuo CC, Lin CY, Shih YL, Hsieh CB, Lin PY, Guan SB, et al. Frequent methylation of HOXA9 gene in tumor tissues and plasma samples from human hepatocellular carcinomas. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52(8):1235–45.

Ji XF, Fan YC, Gao S, Yang Y, Zhang JJ, Wang K. MT1M and MT1G promoter methylation as biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(16):4723–9.

Huang G, Krocker JD, Kirk JL, Merwat SN, Ju H, Soloway RD, et al. Evaluation of INK4A promoter methylation using pyrosequencing and circulating cell-free DNA from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52(6):899–909.

Han LY, Fan YC, Mu NN, Gao S, Li F, Ji XF, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation of G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor Gpbar1 (TGR5) is a potential biomarker for hepatitis B virus associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(2):164–71.

Zhang P, Wen X, Gu F, Deng X, Li J, Dong J, et al. Methylation profiling of serum DNA from hepatocellular carcinoma patients using an Infinium human methylation 450 BeadChip. Hepatol Int. 2013;7(3):893–900.

Sun FK, Fan YC, Zhao J, Zhang F, Gao S, Zhao ZH, et al. Detection of TFPI2 methylation in the serum of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(4):1010–5.

Piciocchi M, Cardin R, Vitale A, Vanin V, Giacomin A, Pozzan C, et al. Circulating free DNA in the progression of liver damage to hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int. 2013;7(4):1050–7.

Mohamed NA, Swify EM, Amin NF, Soliman MM, Tag-Eldin LM, Elsherbiny NM. Is serum level of methylated RASSF1A valuable in diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic viral hepatitis C? Arab J Gastroenterol. 2012;13(3):111–5.

Iizuka N, Oka M, Sakaida I, Moribe T, Miura T, Kimura N, et al. Efficient detection of hepatocellular carcinoma by a hybrid blood test of epigenetic and classical protein markers. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412(1–2):152–8.

Huang ZH, Hu Y, Hua D, Wu YY, Song MX, Cheng ZH. Quantitative analysis of multiple methylated genes in plasma for the diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;91(3):702–7.

Yang YJ, Chen H, Huang P, Li CH, Dong ZH, Hou YL. Quantification of plasma hTERT DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma patients by quantitative fluorescent polymerase chain reaction. Clin Invest Med. 2011;34(4):E238.

Iyer P, Zekri AR, Hung CW, Schiefelbein E, Ismail K, Hablas A, et al. Concordance of DNA methylation pattern in plasma and tumor DNA of Egyptian hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Exp Mol Pathol. 2010;88(1):107–11.

Szymanska K, Chen JG, Cui Y, Gong YY, Turner PC, Villar S, et al. TP53 R249S mutations, exposure to aflatoxin, and occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort of chronic hepatitis B virus carriers from Qidong, China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18(5):1638–43.

Chang H, Yi B, Li L, Zhang HY, Sun F, Dong SQ, et al. Methylation of tumor associated genes in tissue and plasma samples from liver disease patients. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008;85(2):96–100.

Zhang YJ, Wu HC, Shen J, Ahsan H, Tsai WY, Yang HI, et al. Predicting hepatocellular carcinoma by detection of aberrant promoter methylation in serum DNA. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(8):2378–84.

Tan SH, Ida H, Lau QC, Goh BC, Chieng WS, Loh M, et al. Detection of promoter hypermethylation in serum samples of cancer patients by methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction for tumour suppressor genes including RUNX3. Oncol Rep. 2007;18(5):1225–30.

Ren N, Qin LX, Tu H, Liu YK, Zhang BH, Tang ZY. The prognostic value of circulating plasma DNA level and its allelic imbalance on chromosome 8p in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132(6):399–407.

Iizuka N, Sakaida I, Moribe T, Fujita N, Miura T, Stark M, et al. Elevated levels of circulating cell-free DNA in the blood of patients with hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2006;26(6C):4713–9.

Yeo W, Wong N, Wong WL, Lai PB, Zhong S, Johnson PJ. High frequency of promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A in tumor and plasma of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2005;25(2):266–72.

Chu HJ, Heo J, Seo SB, Kim GH, Kang DH, Song GA, et al. Detection of aberrant p16INK4A methylation in sera of patients with liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19(1):83–6.

Wong IH, Zhang J, Lai PB, Lau WY, Lo YM. Quantitative analysis of tumor-derived methylated p16INK4a sequences in plasma, serum, and blood cells of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(3):1047–52.

Huang XH, Sun LH, Lu DD, Sun Y, Ma LJ, Zhang XR, et al. Codon 249 mutation in exon 7 of p53 gene in plasma DNA: maybe a new early diagnostic marker of hepatocellular carcinoma in Qidong risk area, China. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(4):692–5.

Wong IH, Lo YM, Yeo W, Lau WY, Johnson PJ. Frequent p15 promoter methylation in tumor and peripheral blood from hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(9):3516–21.

Patil MA, Gutgemann I, Zhang J, Ho C, Cheung ST, Ginzinger D, et al. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization reveals recurrent chromosomal aberrations and Jab1 as a potential target for 8q gain in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(12):2050–7.

Krebs MG, Metcalf RL, Carter L, Brady G, Blackhall FH, Dive C. Molecular analysis of circulating tumour cells-biology and biomarkers. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(3):129–44.

Thompson EW, Haviv I. The social aspects of EMT-MET plasticity. Nat Med. 2011;17(9):1048–9.

Yin CQ, Yuan CH, Qu Z, Guan Q, Chen H, Wang FB. Liquid biopsy of hepatocellular carcinoma: circulating tumor-derived biomarkers. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:1427849.

de Boer CJ, van Krieken JH, Janssen-van Rhijn CM, Litvinov SV. Expression of ep-CAM in normal, regenerating, metaplastic, and neoplastic liver. J Pathol. 1999;188(2):201–6.

Went PT, Lugli A, Meier S, Bundi M, Mirlacher M, Sauter G, et al. Frequent EpCam protein expression in human carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(1):122–8.

Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, et al. Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature. 2007;450(7173):1235–9.

Yu X, Wang B, Zhang N, Yin C, Chen H, Zhang L, et al. Capture and release of Cancer cells by combining on-Chip purification and off-Chip enzymatic treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(43):24001–7.

Taly V, Pekin D, Benhaim L, Kotsopoulos SK, Le Corre D, Li X, et al. Multiplex picodroplet digital PCR to detect KRAS mutations in circulating DNA from the plasma of colorectal cancer patients. Clin Chem. 2013;59(12):1722–31.

Kinde I, Wu J, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Detection and quantification of rare mutations with massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(23):9530–5.

Newman AM, Bratman SV, To J, Wynne JF, Eclov NC, Modlin LA, et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat Med. 2014;20(5):548–54.

Forshew T, Murtaza M, Parkinson C, Gale D, Tsui DW, Kaper F, et al. Noninvasive identification and monitoring of cancer mutations by targeted deep sequencing of plasma DNA. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(136):136ra68.

Murtaza M, Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Gale D, Forshew T, Piskorz AM, et al. Non-invasive analysis of acquired resistance to cancer therapy by sequencing of plasma DNA. Nature. 2013;497(7447):108–12.

Rothe F, Laes JF, Lambrechts D, Smeets D, Vincent D, Maetens M, et al. Plasma circulating tumor DNA as an alternative to metastatic biopsies for mutational analysis in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(10):1959–65.

Sun C, Liao W, Deng Z, Li E, Feng Q, Lei J, et al. The diagnostic value of assays for circulating tumor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96(29):e7513.

Zhang Y, Li J, Cao L, Xu W, Yin Z. Circulating tumor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma: detection techniques, clinical implications, and future perspectives. Semin Oncol. 2012;39(4):449–60.

Zhou Y, Wang B, Wu J, Zhang C, Zhou Y, Yang X, et al. Association of preoperative EpCAM circulating tumor cells and peripheral Treg cell levels with early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma following radical hepatic resection. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:506.

Wang Z, Luo L, Cheng Y, He G, Peng B, Gao Y, et al. Correlation between postoperative early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and mesenchymal circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22(4):633-9.

Bergman Y, Cedar H. DNA methylation dynamics in health and disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(3):274–81.

Xu RH, Wei W, Krawczyk M, Wang W, Luo H, Flagg K, et al. Circulating tumour DNA methylation markers for diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Mater. 2017;16(11):1155–61.

Huang Z, Hua D, Hu Y, Cheng Z, Zhou X, Xie Q, et al. Quantitation of plasma circulating DNA using quantitative PCR for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2012;18(2):271–6.

Chen K, Zhang H, Zhang LN, Ju SQ, Qi J, Huang DF, et al. Value of circulating cell-free DNA in diagnosis of hepatocelluar carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(20):3143–9.

Hardy T, Zeybel M, Day CP, Dipper C, Masson S, McPherson S, et al. Plasma DNA methylation: a potential biomarker for stratification of liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2017;66(7):1321–8.

Ren N, Ye QH, Qin LX, Zhang BH, Liu YK, Tang ZY. Circulating DNA level is negatively associated with the long-term survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(24):3911–4.

Tokuhisa Y, Iizuka N, Sakaida I, Moribe T, Fujita N, Miura T, et al. Circulating cell-free DNA as a predictive marker for distant metastasis of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(10):1399–403.

Ono A, Fujimoto A, Yamamoto Y, Akamatsu S, Hiraga N, Imamura M, et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis for liver cancers and its usefulness as a liquid biopsy. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1(5):516–34.

Fan ZC, Yan J, Liu GD, Tan XY, Weng XF, Wu WZ, et al. Real-time monitoring of rare circulating hepatocellular carcinoma cells in an orthotopic model by in vivo flow cytometry assesses resection on metastasis. Cancer Res. 2012;72(10):2683–91.

Nel I, Baba HA, Ertle J, Weber F, Sitek B, Eisenacher M, et al. Individual profiling of circulating tumor cell composition and therapeutic outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2013;6(4):420–8.

Li J, Shi L, Zhang X, Sun B, Yang Y, Ge N, et al. pERK/pAkt phenotyping in circulating tumor cells as a biomarker for sorafenib efficacy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(3):2646–59.

Cai ZX, Chen G, Zeng YY, Dong XQ, Lin MJ, Huang XH, et al. Circulating tumor DNA profiling reveals clonal evolution and real-time disease progression in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(5):977–85.

Jahr S, Hentze H, Englisch S, Hardt D, Fackelmayer FO, Hesch RD, et al. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(4):1659–65.

Thierry AR, El Messaoudi S, Gahan PB, Anker P, Stroun M. Origins, structures, and functions of circulating DNA in oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(3):347–76.

Cortese R, Almendros I, Wang Y, Gozal D. Tumor circulating DNA profiling in xenografted mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia. Oncotarget. 2015;6(1):556–69.

Gai W, Sun K. Epigenetic biomarkers in cell-free DNA and applications in liquid biopsy. Genes. 2019;10(1).

Sun K, Jiang P, Chan KC, Wong J, Cheng YK, Liang RH, et al. Plasma DNA tissue mapping by genome-wide methylation sequencing for noninvasive prenatal, cancer, and transplantation assessments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(40):E5503–12.

Lehmann-Werman R, Neiman D, Zemmour H, Moss J, Magenheim J, Vaknin-Dembinsky A, et al. Identification of tissue-specific cell death using methylation patterns of circulating DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(13):E1826–34.

Moss J, Magenheim J, Neiman D, Zemmour H, Loyfer N, Korach A, et al. Comprehensive human cell-type methylation atlas reveals origins of circulating cell-free DNA in health and disease. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5068.

Guo S, Diep D, Plongthongkum N, Fung HL, Zhang K, Zhang K. Identification of methylation haplotype blocks aids in deconvolution of heterogeneous tissue samples and tumor tissue-of-origin mapping from plasma DNA. Nat Genet. 2017;49(4):635–42.

Snyder MW, Kircher M, Hill AJ, Daza RM, Shendure J. Cell-free DNA comprises an in vivo nucleosome footprint that informs its tissues-of-origin. Cell. 2016;164(1–2):57–68.

Jiang P, Sun K, Tong YK, Cheng SH, Cheng THT, MMS H, et al. Preferred end coordinates and somatic variants as signatures of circulating tumor DNA associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(46):E10925–e33.

Scherer F, Kurtz DM, Newman AM, Stehr H, Craig AF, Esfahani MS, et al. Distinct biological subtypes and patterns of genome evolution in lymphoma revealed by circulating tumor DNA. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(364):364ra155.

Martinez-Ricarte F, Mayor R, Martinez-Saez E. Molecular diagnosis of diffuse gliomas through sequencing of cell-free circulating tumor DNA from Cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(12):2812–9.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the help from Dr. Jimin Liu (Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, NLIU@haltonhealthcare.com) in English language improvement.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2017ZX10203205).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QY collected the related papers and drafted the manuscript. SL revised the manuscript and drafted the figures. SZ and XX participated in the design of the review and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, Q., Ling, S., Zheng, S. et al. Liquid biopsy in hepatocellular carcinoma: circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA. Mol Cancer 18, 114 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-019-1043-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-019-1043-x