Abstract

Background

Air pollution is involved in many pathologies. These pollutants act through several mechanisms that can affect numerous physiological functions, including reproduction: as endocrine disruptors or reactive oxygen species inducers, and through the formation of DNA adducts and/or epigenetic modifications. We conducted a systematic review of the published literature on the impact of air pollution on reproductive function.

Eligible studies were selected from an electronic literature search from the PUBMED database from January 2000 to February 2016 and associated references in published studies. Search terms included (1) ovary or follicle or oocyte or testis or testicular or sperm or spermatozoa or fertility or infertility and (2) air quality or O3 or NO2 or PM2.5 or diesel or SO2 or traffic or PM10 or air pollution or air pollutants. The literature search was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We have included the human and animal studies corresponding to the search terms and published in English. We have excluded articles whose results did not concern fertility or gamete function and those focused on cancer or allergy. We have also excluded genetic, auto-immune or iatrogenic causes of reduced reproduction function from our analysis. Finally, we have excluded animal data that does not concern mammals and studies based on results from in vitro culture. Data have been grouped according to the studied pollutants in order to synthetize their impact on fertility and the molecular pathways involved.

Conclusion

Both animal and human epidemiological studies support the idea that air pollutants cause defects during gametogenesis leading to a drop in reproductive capacities in exposed populations. Air quality has an impact on overall health as well as on the reproductive function, so increased awareness of environmental protection issues is needed among the general public and the authorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

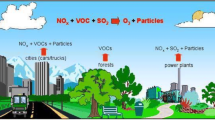

For decades, a causal relationship has been suspected between air pollution and some human health problems. Particulate matter (PM) and ground-level ozone (O3) are Europe’s most problematic pollutants in terms of harm to human health, followed by benzo (a) pyrene (BaP) (an indicator for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) [1]. The main sources of these pollutants are transport and energy followed by industry. Air pollution is involved in cardiovascular disease [2], stroke [3] and respiratory diseases [4, 5] such as lung cancer [6], childhood asthma [7] and atopic dermatitis [8]. Furthermore, perinatal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and particulate matter (PM) has been demonstrated to have a negative impact on neuropsychological development in children [9]. A study carried out in Sydney estimated that reducing particulate matter (PM2.5) by 10% for 10 years would avoid approximately 650 premature deaths [10]. According to Lelieveld et al., model projections based on a business-as-usual emission scenario indicate that the contribution of outdoor air pollution to premature mortality could double by 2050 [11].

Several mechanisms of action may be involved in these health impacts: (1) Endocrine disruptor activity: This is the case of the PAHs and heavy metals (Cu, Pb, Zn, etc.) contained in particulate matter, especially from diesel exhaust [12,13,14,15]. Diesel exhaust particles contain for example substances with estrogenic, antiestrogenic and antiandrogenic activities that can affect gonadal steroidogenesis and gametogenesis. (2) Generation of oxidative stress: NO2, O3 or PM (through the heavy metals and PAHs they contain) can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) [16,17,18]. These cause alterations in DNA, proteins and membrane lipids [19, 20]. (3) Modifications of DNA: Through the formation of DNA adducts, leading to modifications in gene expression and/or the appearance of epigenetic mutations or modifications such as an alteration of DNA methylation [21,22,23].

These are general mechanisms that can affect all functions, including procreation.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate our current understanding of air pollution’s impact on reproductive functions. The results of such a review could sensitize the population and the authorities to take care of air quality.

Methods

Research strategy

We have conducted a systematic review of the literature concerning the exposure to environmental air pollutants and fertility or reproductive health. This analysis was made in compliance with the PRISMA criteria: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [24]. We conducted the research in April 2016 using the PubMed database. All of the research was done using the Advanced Search Builder and the key words were searched in [Title OR Abstract]. Over the period from 01/01/2000 and 04/01/2016, we filtered the hits by selecting articles written in English.

Regarding fertility, we used comprehensive terms in order to optimize the search. Regarding the air quality, we opted for a strategy that combined comprehensive terms and pollutant names so as not to omit any articles.

Therefore, the search was as follows:

(((((((((((((((((air quality [Title/Abstract]) OR O3[Title/Abstract]) OR NO2 [Title/Abstract]) OR Ozone[Title/Abstract]) OR PM2.5 [Title/Abstract]) OR diesel [Title/Abstract]) OR SO2[Title/Abstract]) OR traffic[Title/Abstract])) OR PM10 [Title/Abstract])) OR air pollution[Title/Abstract]) OR air pollutants [Title/Abstract]) AND (“2000/01/01” [PDat]: “2016/04/01” [PDat]))) AND ((((((((((((ovary [Title/Abstract]) OR follicle*[Title/Abstract]) OR follicular [Title/Abstract]) OR ovaries [Title/Abstract]) OR oocyte*[Title/Abstract]) OR testis [Title/Abstract]) OR testicular [Title/Abstract]) OR sperm [Title/Abstract]) OR spermatozoa [Title/Abstract]) OR fertility [Title/Abstract]) OR infertility [Title/Abstract]) AND (“2000/01/01” [PDat]: “2016/04/01” [PDat]))) NOT ((((Cancer [Title/Abstract]) OR allergy [Title/Abstract]) OR bacteria [Title/Abstract]) AND (“2000/01/01” [PDat]: “2016/04/01” [PDat]))) AND “english” [Language].

Article inclusion and exclusion criteria

We have included all of the human and animal studies arising from the search.

We have excluded articles that included results that did not concern fertility, those focused on ovarian cancer, polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis or precocious puberty. Finally, we have excluded animal data that do not concern mammals and studies based on results from in vitro culture (Fig. 1). However, non-mammal and in vitro studies were included for informing the mechanisms of pollutants’ action.

Results

Impact of air pollution on spontaneous fertility (Table 1)

Few studies carried out on animals suggest a negative impact of exposure to air pollution on spontaneous fertility [25, 26]. Two studies were carried out on mice in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil, which has a high level of air pollution. Mohallem et al. found a significant reduction in the number of newborns per mouse and a significant increase in the embryo implantation failure rate in female mice exposed as newborns for 3 months to the city polluted air and then mated with non-exposed males as adults [27]. No effect was evidenced when exposure occurred during adulthood. Veras et al., on the other hand, reported a significant increased number of days in estrus over the studied period (mean (SD): 56.63 (11.65) vs 34.57 (6.68); p < 0.03), a reduction in the number of ovarian antral follicles (mean (SD): 75 (35.2) vs 118.6 (18.4); p < 0.04), an increase in the time to mating as well as a significant decrease in the fertility index (number of pregnant females/total number of females, Table 1) in adult mice exposed to pollution from automobile traffic [28].

Studies carried out on humans in different countries have produced concordant results regarding an impact of polluted air on human fertility although they are discordant regarding the type of air pollutant concerned. In Teplice, a highly polluted district in Czech Republic, Dejmek and colleagues have studied the effect of SO2 exposure during the 4 previous months before conception in a birth cohort of 2585 parental pairs. They found a significantly negative impact of sulfur oxide (SO2) exposure in the second month before conception on fecundability rate (assessed as the pregnancy rates after the 1st menstrual cycle without contraception): the adjusted odd ratios were 0.57 (CI, 0.37–0.88; p< 0.011) in case of medium level exposure (40–80 pg/m3) and 0.49 (CI 0.29–0.8 1; p< 0.006) in case of high level exposure (>80 pg/m3) compared with the reference exposure (<40 pg/m3) [29]. Because in this study the exposure window was retrospectively defined with respect to the date of conception, Slama et al. reanalyzed the data after defining exposure window with respect to the start of unprotected intercourse and examined the effects of others air pollutants. Slama et al. did not confirm the effect of SO2 exposure before conception but they observed that each increase of 10 μg/m3 in PM2.5 concentration was associated with a 22% decrease in fecundability (95% CI = 6–35%). Among the other air pollutants studied (PAH, O3, NO2), only NO2 levels were significantly associated with a decreased fecundability in the first month (adjusted Fecundability Ratio (FR) = 0.71 [95% CI = 0.57–0.87]) and two first months (adjusted FR: 0.72 [95% CI: 0.53–0.97])of unprotected intercourse [30]. In Barcelona, using a cross-sectional study based on registry data at census tract level and a land use regression modeling approach, Nieuwenhuijsen et al. reported a statistically significant link (detailed in Table 1) between a decrease in the fertility rate (number of live births per 1000 women) and an increase in the level of air pollution, notably PM2.5–10 [31]. Lastly, in a recent study, Mahalingaiah et al. compared the risk of infertility in over 36,000 nurses as a function of their exposure to air pollution at their place of residence. In a multivariate analysis, they observed a significantly positive association between infertility and the proximity (<200 m) of the residence to a main road (Hazard Ratio [95% CI] for infertility when living closed to major roads compared to farther = 1.11 (CI: 1.02–1.20), and between infertility and the level of PM2.5–10. They therefore concluded that air pollution has a potentially harmful effect on fertility [32].

In conclusion, both animal and human data are not strong enough to point to a single air pollutant as responsible for a decrease in spontaneous fertility. Most of human data come from retrospective studies, based on declarative answers, predicted/modeled exposure levels and fail to take into account important confounders such as tobacco exposure. However, the only prospective human study based on a large population (36,294 women) and precise geolocalization data, found an impact of the proximity of residential address to major roads on the risk of infertility [32], which corroborates the results from mice studies [27, 28].

Impact of air pollution in vitro fertilization (IVF) outcomes (Table 2)

Studying IVF populations helps provide evidence on the effects of air pollution on human reproduction since it allows to accurately time the key events in ovulation, fertilization and implantation. In this section, we excluded studies on the influence of air quality at IVF laboratories to concentrate on the effects of pollutants on patients undergoing IVF. The influence of environmental factors on assisted reproductive technology (ART) results, and notably on IVF techniques, has been suspected for many years [33], but the specific effects of air pollution on IVF have been little studied in the literature [26].

In 7403 women undergoing their first IVF cycle, Legro et al. assessed the effects of various air pollutants (SO2, NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10) along 4 different steps of the procedure: from the first day of ovarian stimulation to oocyte retrieval (T1); from oocyte retrieval to embryo transfer (T2); from embryo transfer to pregnancy test (T3) and from embryo transfer to pregnancy outcome (T4) [34]. They found negative impacts of a one standard deviation increase in NO2 concentrations on live births in all stages of the IVF cycle except T4 (Table 2). However this impact was stronger when the increase in NO2 concentrations occurred in T3 (Odd ratio (95%CI) for of live birth: 0.76 (0.66–0.86). Although, a biphasic effect of O3 exposure was seen, with a positive effect on live birth when exposure took place before embryo implantation and a negative effect after embryo implantation, no significant effects were observed in the live birth rate for other pollutants after adjusting for NO2 exposure.

Furthermore, in their study of the impact of short-term exposure (14 days after the date of the last menstrual period) to large particulate matter (PM10) on the results of IVF in about 400 women, Perin et al. did not observe any influence of exposure to PM10 on the ovarian stimulation parameters (number of days of treatment, ovarian response, etc.), on the biological parameters (number of oocytes gathered, fertilization rate, embryo morphology, etc.), or on the rates of embryo implantation and pregnancy. On the other hand, they found a statistically significant increase of 5% in the risk of early pregnancy loss per unit increase in follicular phase PM10 exposure, leading to an increased rate of early miscarriages among women exposed to the highest quartile of concentrations of PM10 [35]. In another study on 531 pregnant women, the same authors found that women exposed to high concentrations of large particulate matter (PM10) during the follicular phase of the ovarian cycle had a two-fold increased rate of early miscarriages, no matter if the conception was natural or the result of IVF [36].

Regarding animal data, Maluf et al. assessed the effects of exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from automobile traffic on the development of mouse embryos obtained through IVF from female mice exposed or not to PM2.5 during their pre- or postnatal period until sexual maturity [37]. They did not find any difference between exposed and unexposed mice in terms of the ovarian response to stimulation and the number of blastocysts obtained. However, they did observe a significant effect of PM2.5 exposure on the cell lineage allocation at the blastocyst stage between inner cell mass (ICM i.e. cells participating in the ontogeny of the future fetus) and trophectoderm (TE i.e. cells participating in the ontogeny of the future placenta). Indeed, although similar total blastocyst cells number were found, the number of cells in ICM were significantly increased in unexposed animals (30.06 ± 6.32) compared to pre and postnatally exposed (24.08 ± 4.79) or only postnatally exposed animals (24.45 ± 5.58). Oppositely, the number of cells in TE was decreased in blastocysts from unexposed animals leading to a weaker ICM/TE ratio in exposed animals by about 25%. It is well known in mice [38, 39], that a modified ICM/TE ratio impact on the blastocyst implantation potential and post-implantation outcome. In humans, although this ratio cannot be implemented in a clinical setting, the morphological grading of ICM and TE is linked with embryo ploidy [40] and impacts on blastocyst potential even in euploid blastocysts [41].

In another study, in vitro exposure of mice embryos to diesel exhaust particles extracted from the exhaust pipe of a bus from the Sao Paulo’s public transportation fleet, showed a negative dose-dependent effect on early embryo development and the hatching process, blastocyst cell allocation, ICM morphology and embryonic cells apoptosis [42].

Altogether, the data from the 3 available human studies about air quality and IVF results provide a weak level of evidence because they consist in retrospective studies, with long observation periods (7 [34] to 10 years [35, 36] during which effectiveness of IVF procedures may have improved), with approximated exposures based either on estimated levels from national models of air quality [34] or on average daily exposure of an entire city [35, 36], without accounting for the exact home address [35, 36] or its distance from the nearest monitoring station [34] or with residual confounding from tobacco exposure [34]. Furthermore, the results of these studies are discordant regarding PM10, the only air pollutant commonly evaluated by these studies. This could be due to large differences in PM10 levels between the study sites. Therefore other studies, ideally prospective, are needed to confirm the impact of air pollutants on human ART results.

Impact of air pollution on the male gamete

In animals (Table 3)

Studies carried out on animals have found that various forms of air pollution have harmful effects on sperm quality. A statistically significant decrease in the daily production of spermatozoa has been reported along with an increase in abnormal sperm shapes in mice and rats exposed to car exhaust, notably from diesel vehicles [43,44,45,46,47]. An effect on the nuclear quality of spermatozoa has also been reported [48]. Yauk et al. observed a statistically significant increase in sperm DNA breakage and sperm DNA hypermethylation in mice exposed to ambient air pollution in a Canadian city [22]. These observations were associated with a statistically significant increase in the rate of mutations found in sperm DNA, especially on the loci of DNA sequence repeats. This last phenomenon raises the possibility of genetic mutations in the DNA of germline cells (spermatozoa in this case), that are transmissible to descendants [49].

On the testicular level, Yoshida et al. have observed structural changes in Leydig cells [43], while Watanabe has reported a reduction of Sertoli cells in rats exposed to diesel exhaust [44]. On the hormonal level, Jeng and Yu have demonstrated that extended exposure to PAHs leads to a reduction in blood testosterone levels and an increase in LH levels at the end of the exposure period [46]. Similarly, Inyang et al. found a statistically significant decrease in blood testosterone levels and an increase LH levels in rats exposed to benzo (a) pyrene, a type of PAH [50]. On the other hand, in their study on rats, Tsukue et al. described hormonal modifications in the group exposed to diesel exhaust with a statistically significant increase in blood testosterone levels and LH levels, associated with changes in the weight of the accessory sex glands (prostate, seminal vesicles) [51]. Watanabe and Oonuki also reported a statistically significant increase in the levels of estrogens and testosterone and a significant decrease in LH and FSH levels in a group of rats exposed to diesel exhaust. Furthermore, they observed an increase in the number of degenerative cells between the spermatocyte and spermatid stages [47].

In humans (Table 4)

Over the past few decades, a decline in the quality of sperm has been observed in industrialized countries [52, 53]. One possible reason for this alteration appears to be exposure to toxic substances in the environment, and notably ambient air pollution [54,55,56]. It has indeed been demonstrated that professions exposed to exhaust, such as toll collectors working on expressways, more frequently develop sperm abnormalities [16, 57].

The literature on this subject is rich, but the existing studies are not always comparable because they do not necessarily concern the same pollutants and their methodologies often differ in terms of study populations, and duration and period of exposure. Moreover, their results are sometimes discordant.

Nonetheless, most of the studies find alterations in sperm parameters after exposure to air pollution, providing evidence for a decrease in sperm quality. These alterations involves a reduction in sperm mobility [54, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62], or in the quality of their movement [54, 56]. Altered sperm morphology with a reduction in the percentage of normal shapes, notably the morphology of the head, is also frequently mentioned [21, 56, 57, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. There are discordant results for sperm counts, with some studies reporting a significant decrease in the sperm concentration in semen after exposure to certain forms of air pollution [56, 57, 60, 65, 67], whereas others not observing any significant effects [59, 64, 68]. The same is true for proportion of alive spermatozoa (sperm vitality), with a small number of studies finding a significantly negative effect of air pollution on this parameter [54, 62].

In their study, Guven et al. compared sperm parameters among men exposed to exhaust from diesel vehicles through their work at toll plazas on expressways to unexposed men working as office personnel in the same company. The exposed group had a statistically significant decrease in sperm counts, sperm mobility and sperm morphology notably cephalic defects [57]. Selevan et al. studied sperm parameters in healthy young men from two regions of the Czech Republic, a coal-producing region with high levels of air pollution (Teplice) and a less-polluted region (Prachatice). Compared to low level of exposure, they found a statistically significant negative impact of exposure to medium and high levels of air pollution on the proportion of motile sperm (respectively for low, medium and high exposure: 36.2% ± 17; 27.9% ± 18.1 and 32.5% ± 13.2). The same was true for sperm morphology, notably sperm heads. On the other hand, compared to low level of exposure, they did not evidence an effect of medium or high exposure to air pollution on total sperm count (respectively: for low, medium and high exposure: 113.5 ± 130.7 million/ejaculate; 100.9 ± 97.6 and 129.1 ± 103.1) [59]. The same team found a statistically significant increase in the percentage of spermatozoa with abnormal chromatin (abnormalities in DNA compaction and fragmentation) in men exposed to high levels of air pollution in the Teplice district of Czech Republic [68]. These studies thus suggest that air pollution may alter sperm DNA [48, 69].

Alongside these observations, other authors also reported a possible effect of air pollution on the sperm genome at the chromosomal level [60, 70]. Thus, Jurewicz et al. [70] measured the aneuploidy rate in the sperm of Polish men with normal sperm concentrations (> or = 15 million/ml) consulting for infertility. After adjustment for 12 confounding factors such as age, smoking, alcohol consumption, season, past diseases, abstinence interval, distance from the monitoring station, they observed a significant association between the aneuploidy rate and exposure to certain air pollutants, notably Y-chromosome disomy and PM2.5 (β = 0.68 (95% CI: 0.55–0.85)), disomy 21 and PM10 (β = 0.58 (95% CI: 0.46–0.72)) and PM2.5 (β = 0.78 (95% CI: 0.62–0.97)).

Lastly, as is the case in animals, some authors reported a change in the circulating levels of hormones in the gonadal axis following exposure to air pollution. De Rosa et al. compared a group of exposed men working at a toll plaza on an expressway to an unexposed group working as clerks, drivers, students or doctors and living in the same geographical area. Along with an alteration of sperm parameters (other than ejaculate volume and sperm count), they observed a significantly higher level of FSH in the exposed group (mean ± SE: 4.1 ± 0.3 UI/l vs 3.2 ± 0.2; p < 0.05), although this remained within the normal value range [54]. Radwan et al. [66] also found a negative association between testosterone levels and exposure to certain air pollutants (PM10, PM2.5, CO and NOx).

The evidence for air pollution’s harmful effect on male reproductive parameters is therefore strong. It may also favor a decrease in male fertility. However, the vast majority of the human studies are retrospective. Our search found only one prospective study over a 2-year period in young, non-smoker healthy sperm donors from Los Angeles, California [67]. The population was quite small (n = 48) and only sperm concentration and motility were studied. However, each donor provided at least 10 times during the studied period. Only O3 exposure showed a significant impact on sperm parameters among the 4 air pollutants estimated at place of residence (O3, NO2, CO and PM10) after adjustment for numerous factors including abstinence period and the other air pollutants. For exposure up to 9 days before semen collection, there was a 4.22% decrease in sperm concentration per interquartile range (IQR) of increase in O3 (p = 0.01). For exposure 10–14 days and 70–90 days before ejaculation, there were 2.92% and 3.90% decreases in sperm concentration per IQR of increase in O3, respectively (p = 0.05 in both cases). More longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the negative impact of air pollution on human semen parameters.

Impact of air pollution on the female gamete (Table 5)

Contrary to the male aspect, very few studies have been carried out on the impact of air pollution on female reproductive parameters in spontaneous fertility. This is likely explained by the difficulties involved in such studies. Indeed, it is easier to gather and study male gametes. A small number of authors have nonetheless looked into this subject.

In animals

Veras et al. compared a group of mice exposed to air polluted by automobile traffic in Sao Paulo to a group of mice exposed to less polluted filtered air. The authors observed a significant lengthening of the cycles as well as a decrease in the number of antral follicles in the exposed vs. unexposed groups, but they did not observe a significant effect on follicles at other stages of follicular development (i.e primordial, primary follicles and secondary follicles) [28].They therefore concluded that air pollution has a potentially toxic effect on ovary. Such effect was demonstrated later by the same group comparing the ovarian histology of female mice exposed to diesel exhaust (notably PM2.5) in utero and/or during the postnatal period to unexposed mice [71]. While exposure levels were considered acceptable by the World Health Organization, ovaries showed a statistically significant decrease in the proportion of the area occupied by primordial follicles in exposed mice in all exposure periods (prenatal exposure (from day of vaginal plug to birth); postnatal exposure (from birth until sexual maturity defined as post-natal day 60) or both) compared to unexposed mice. Thus, the authors concluded that there may be a possible decrease in ovarian reserve and therefore in the reproductive potential of mice following exposure to diesel exhaust, notably PM2.5 [71]. However, while the investigators planned to maintain PM2.5 exposure levels within acceptable daily ranges as defined by the World Health Organization (25 μg/m3/d), the daily average exposure was obtained from a 1 h exposure to a much higher level (660 μg/m3). Such an acute exposure could drastically impact the results.

In humans

Only three studies have been carried out among women. Two cross sectional studies have observed the length of menstrual cycles in large populations of women who worked in the petrochemical industry in China and were exposed to organic solvents. Thurston et al. studied the effect of an occupational exposure to benzene (a highly volatile monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbon) evaluated by self-report. They found that the adjusted odds of menstrual cycle abnormalities (fewer than 21 or more than 35 days) did not change significantly during the first 7 years of exposure. However after 7 years, the odds ratio increased to 1.71 (95% CI 1.27–2.31) per additional 5 years of exposure [72]. Cho et al. used a more objective exposure evaluation based on an industrial hygiene evaluation classifying each workplace according to the presence or absence of four organic solvents (benzene, toluene, styrene, and/or xylene) using the information on production steps in the processing of petrochemicals. They described a higher frequency of women with oligomenorrhea (menstrual cycles exceeding 35 days) in the group exposed to styrene, xylene or all solvents. Furthermore, one additional year of exposure to any solvent significantly increased the odds ratio by 7% (CI95%: 1.00–1.14) and a duration of work greater than 3 years yielded an adjusted odds ratio for oligomenorrhea of 1.53 (95% CI:1.00–2.34) [73]. Therefore, these two studies argue for an exposure duration-response relationship for aromatic solvents.

Tomei et al. studied the impact of exposure to pollutants on female police officers assigned to traffic control in Rome compared to a matched-control group of female police officers assigned to indoor activities such as administrative and bureaucratic duties. They found an average level of estradiol that was statistically significantly lower in the exposed group in the follicular phase and luteal phase of the cycle, but not in the ovulatory phase. Although no statistically significant difference between the two groups was noted in terms of disruption of the menstrual cycle, the authors suggest that these hormonal changes could alter ovulation in exposed women [74].

Although these three studies suggest that air pollution may have an impact on female reproductive parameters, notably at the ovarian level, questions remain about whether the pollutants have a direct or indirect effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal regulation.

Mechanisms of action of air pollutants

Four possible mechanisms have been put forward in the literature for the mechanism of action of air pollutants on fertility: hormonal changes due to an endocrine disruptor action, oxidative stress induction, cell DNA alteration or epigenetic modifications. Air pollutants can act as endocrine disruptors mainly through activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) or estrogen or androgen receptors [75]. Another common cellular mechanism by which most air pollutants exert their adverse effects is their ability to act directly as prooxidants of lipids and proteins or as free radicals generators, promoting oxidative stress and the induction of inflammatory responses [76]. Some pollutants can alter the DNA molecule or induce epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications which can be transmitted to future generations.

Action as endocrine disruptors

Air pollutants notably the PAHs and heavy metals (such as Cu, Pb, Zn, etc.) contained in PM, especially from diesel exhaust [12, 13], are described in the literature as endocrine disruptors with either estrogenic, anti-estrogenic or anti-androgenic activity [14, 77,78,79,80,81].

Kizu et al. described anti-androgenic activity of certain particle compounds from diesel exhaust in human PC3/AR cells derived from prostate cancer tumors [15], while Okamura et al. reported anti-estrogenic activity of similar compounds in human MCF-7 cells from breast cancer tumors [14]. In vivo studies carried out on rats found significant changes in the circulating levels of sex steroids and gonadotrophins in groups exposed to diesel exhaust, associated with a decrease in the daily production of sperm, demonstrating inhibited spermatogenesis, as well as morphological changes to germ cells in the seminiferous tubules [46, 47, 50, 51]. Likewise, in their study on mice, Yoshida et al. reported a significant decrease in the level of messenger RNA expression in LH receptors of Leydig cells, and altered morphology of the seminiferous tubules and Leydig cells in the group exposed to diesel exhaust [43].

In men, a small number of studies describe a change in the circulating levels of hormones in the gonadal axis following exposure to air pollution. For example, De Rosa et al. found an alteration in sperm parameters associated with significantly higher levels of FSH in the group exposed to exhaust, although they remained within the normal value range [54], while Radwan et al. reported a negative association between testosterone levels and exposure to certain air pollutants (PM10, PM2.5, CO and NO2) [66].

These hormone disruptions may be induced by air pollutants, notably PAHs, binding to estrogen receptors [78, 79, 82, 83] or androgen receptors [15, 84] with an agonistic or antagonistic effect. They may also be the result of activation of AhR pathway. This is a transcription factor activated by a large number of ligands, including PAHs [82, 83, 85, 86] and involved in many cell processes. For example, extractable organic matter (EOM) from PM2.5 may cause heart malformations and decreased heart rates in zebrafish embryos through the AhR, and these heart defects appear to be counteracted in embryos co-exposed to EOM and an AhR antagonist [87, 88]. Concerning the male reproductive system, Izawa et al. have reported a decrease in the daily production of spermatozoa, an increase in morphological abnormalities in spermatozoa as well as a significant increase in blood testosterone levels in the group exposed to diesel exhaust combined with a significant increase in the AhR activity index [89]. Using strains of mouse with different AhR activity index, they showed that the decrease in daily sperm production due to diesel exhaust exposure was negatively correlated with this index (r = −0.593; p = 0.008) [90]. Concerning the female reproductive system, AhR may regulate ovarian follicle growth, modulate ovarian steroidogenesis and play a role in ovulation [91]. It also appears to relay the toxicity of certain ligands, such as PAHs, notably in the reproductive system, where it may be one of the mediators in steroid hormone disruption and therefore in fertility [89, 90, 92].

Induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Most air pollutants such as NO2are ROSor are capable of generating them, such as O3 or PM, through the heavy metals and the PAHs they contain. They can be transformed by CYP450 dihydro-dehydrogenase, which produces quinone redox, catalyzing electron transfer reactions and thus stimulating ROS production [93, 16,17,18].

For males, several studies have described the potentially harmful effects of oxidative stress on sperm. While a certain amount of ROS is needed for the physiological functions of spermatozoa, notably for the fertilization process, an excess amount may cause damage to the spermatozoa [93]. Indeed, the sperm membrane comprises a large number of polyunsaturated fatty acids that maintain the membrane’s fluidity, making sperm highly sensitive to oxidative stress. Peroxidation of these fatty acids can cause a loss of this fluidity as well as a decrease in activity of the membrane enzymes and the ion channels, and can thus alter sperm mobility and some of the mechanisms needed for fertilizing the oocyte. Furthermore, peroxidation of the sperm DNA bases could lead to breakage of the DNA strands and genetic mutations, causing a decrease in the sperm’s fertilization potential, along with an alteration of subsequent embryo development. The protein oxidation induced by ROS may also alter sperm functions by splitting the polypeptide chains and an accumulation of protein aggregates. Lastly, ROS may initiate chain reactions leading to apoptosis, notably by altering mitochondrial membrane integrity. This process could be sped up by the damage to the DNA and the sperm membrane, possibly leading to a decreased sperm count [94,95,96,97,98].

For women, ROS are produced during folliculogenesis and they also appear to play a physiological role, notably in renewed oocyte meiosis I and in inducing ovulation [99, 100]. Excess ROS, however, leads to a state of oxidative stress and appears to be harmful to ovarian functions. In their study of mutated mice with a deficit of glutathione, the most abundant intracellular antioxidant, Lim et al. described a faster decrease in the number of ovarian follicles in these mutated mice, related to an acceleration in primordial follicle depletion [101]. They also reported a higher percentage of small follicles with a heavy proliferation of granulosa cells, reflecting the accelerated recruitment of primordial follicles. They therefore concluded that oxidative stress in the ovaries may lead to a decrease in the ovarian reserve by speeding up the depletion of primordial ovarian follicles by increasing recruitment from the follicle pool and apoptosis at the most advanced stages of follicle development.

Cell DNA alteration

The third mechanism reported in the literature to explain the pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in fertility alteration caused by air pollution is the induction of alterations in the cell DNA.

First, these DNA alterations could be linked to induced oxidative stress, as described above. Indeed, the inflammation processes due to ROS can alter DNA as reported in a study of taxi drivers [102]. Moreover, telomere length has been reported to increase with increasing annual exposure to NOx, PM2.5 and PM10 [103].

Second, they may occur after the formation of DNA adducts. Indeed, some molecules are able to bind to a DNA base through covalent bonding, thus modifying gene expression. In addition, mutations may occur, leading to an alteration of the cell DNA and increased risk of apoptosis. Some air pollutants are capable of forming DNA adducts in germ cells, notably the PAHs contained in PM [21, 46, 68].

Epigenetic modifications

Epigenetic modifications, notably changes in DNA methylation, can lead to abnormal gene expression. These abnormalities have been implicated in the effect of air pollution on carcinogenesis [104] and respiratory failure [105, 106]. In rats exposed to PM2.5, PM10 and NO2, Ding et al. have demonstrated both hypomethylation and hypermethylation of certain genes [107]. These changes can also affect mitochondrial (mt) DNA [108]. Byun et al. have shown that blood mtDNA methylation in the D-loop promoter was associated with PM2.5 levels [109] Epigenetic alterations have been also reported as involved in the failure of spermatogenesis [110]. In the study of Stouder et al. [111] alcohol administration in pregnant mice induced hypomethylation of H19 imprinted gene and may have contributed to the decreased spermatogenesis. In another study [112], Park et al. have shown that long-term exposure to butyl paraben (BP) can cause DNA hypermethylation from the mitotic through post-meiotic stage in adult rat testes.

Lastly, air pollutants have also been shown to alter microRNA (miRNA). A study by Tsamou et al. has shown that the placental expression of miR-21, miR-146a and miR-222, three miRNA known to be expressed in the placenta and to be affected by air pollution exposure in leucocyte blood cells, was inversely associated with PM2.5 exposure during the 2nd trimester of pregnancy [113].

Conclusion

Air pollution has a negative impact on both male and female gametogenesis. These impacts not only influence the quantity of gametes but also on their quality on a genetic and epigenetic level. These impacts also alter the embryo development.

Most prior studies concern male gametes, probably due to the ease of obtaining and analyzing them, and few prior studies have focused on oocytes and folliculogenesis. Studies have also shown an impact on fetal development, with an increase in miscarriages.

The individual role of specific pollutants is difficult to identify, since subjects in the epidemiological studies are typically exposed to several pollutants simultaneously.

The physiopathology leading to altered fertility is poorly understood. Hormonal disturbances, oxidative stress induction, cell DNA and epigenetic alterations are four mechanisms put forward in the literature, probably working in combination, to explain this negative impact.

As air pollution is ubiquitous and has many origins, it would seem to be indispensable to increase awareness among the population and public authorities to attempt to limit air pollutants as much as possible.

Abbreviations

- AhR:

-

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- ART:

-

assisted reproductive technologies

- DNA:

-

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EOM:

-

extractable organic matter

- FSH:

-

follicle stimulating hormone

- IVF:

-

in vitro fertilization

- LH:

-

luteinizing hormone

- miRNAs:

-

micro ribonucleic acid

- NO2 :

-

nitrogen dioxide

- NOx:

-

nitrogen oxides

- O3 :

-

ozone

- PAH:

-

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- PM:

-

particulate matter

- ROS:

-

reactive oxygen species

References

Air quality in Europe - 2014 report [http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2014].

Cosselman KE, Navas-Acien A, Kaufman JD. Environmental factors in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015; doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2015.152.

Shah AS, Lee KK, McAllister DA, Hunter A, Nair H, Whiteley W, Langrish JP, Newby DE, Mills NL. Short term exposure to air pollution and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015; doi:10.1136/bmj.h1295.

Atkinson RW, Kang S, Anderson HR, Mills IC, Walton HA. Epidemiological time series studies of PM2.5 and daily mortality and hospital admissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2014; doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204492.

Karakis I, Kordysh E, Lahav T, Bolotin A, Glazer Y, Vardi H, Belmaker I, Sarov B. Life prevalence of upper respiratory tract diseases and asthma among children residing in rural area near a regional industrial park: cross-sectional study. Rural Remote Health. 2009;1092

Lemjabbar-Alaoui H, Hassan OU, Yang YW, Buchanan P. Lung cancer: biology and treatment options. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.08.002.

Jassal MS. Pediatric asthma and ambient pollutant levels in industrializing nations. Int Health. 2015; doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihu081.

Ahn K. The role of air pollutants in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014; doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.023.

Suades-Gonzalez E, Gascon M, Guxens M, Sunyer J. Air pollution and neuropsychological development: a review of the latest evidence. Endocrinology. 2015; doi:10.1210/en.2015-1403.

Broome RA, Fann N, Cristina TJ, Fulcher C, Duc H, Morgan GG. The health benefits of reducing air pollution in Sydney. Australia Environmental research. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.envres.2015.09.007.

Lelieveld J, Evans JS, Fnais M, Giannadaki D, Pozzer A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature. 2015; doi:10.1038/nature15371.

Takeda K, Tsukue N, Yoshida S. Endocrine-disrupting activity of chemicals in diesel exhaust and diesel exhaust particles. Environ Sci. 2004;195:11:33–45.

Wang J, Xie P, Kettrup A, Schramm KW. Inhibition of progesterone receptor activity in recombinant yeast by soot from fossil fuel combustion emissions and air particulate materials. Sci Total Environ. 2005; doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.01.019.

Okamura K, Kizu R, Toriba A, Murahashi T, Mizokami A, Burnstein KL, Klinge CM, Hayakawa K. Antiandrogenic activity of extracts of diesel exhaust particles emitted from diesel-engine truck under different engine loads and speeds. Toxicology. 2004;195(2-3):243–54.

Kizu R, Okamura K, Toriba A, Mizokami A, Burnstein KL, Klinge CM, Hayakawa K. Antiandrogenic activities of diesel exhaust particle extracts in PC3/AR human prostate carcinoma cells. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2003; doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfg230.

Arbak P, Yavuz O, Bukan N, Balbay O, Ulger F, Annakkaya AN. Serum oxidant and antioxidant levels in diesel exposed toll collectors. J Occup Health. 2004:281–8.

Cho AK, Sioutas C, Miguel AH, Kumagai Y, Schmitz DA, Singh M, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Froines JR. Redox activity of airborne particulate matter at different sites in the Los Angeles Basin. Environmental Res. 2005; doi:10.1016/j.envres.2005.01.003.

Sklorz M, Briede JJ, Schnelle-Kreis J, Liu Y, Cyrys J, de Kok TM, Zimmermann R. Concentration of oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and oxygen free radical formation from urban particulate matter. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007; doi:10.1080/15287390701457654.

Slimen IB, Najar T, Ghram A, Dabbebi H, Ben Mrad M, Abdrabbah M. Reactive oxygen species, heat stress and oxidative-induced mitochondrial damage. A review Int J Hyperthermia. 2014; doi:10.3109/02656736.2014.971446.

Poljsak B, Fink R. The protective role of antioxidants in the defence against ROS/RNS-mediated environmental pollution. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2014; doi:10.1155/2014/671539.

Gaspari L, Chang SS, Santella RM, Garte S, Pedotti P, Taioli E. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts in human sperm as a marker of DNA damage and infertility. Mutat Res. 2003:155–60.

Yauk C, Polyzos A, Rowan-Carroll A, Somers CM, Godschalk RW, Van Schooten FJ, Berndt ML, Pogribny IP, Koturbash I, Williams A, et al. Germ-line mutations, DNA damage, and global hypermethylation in mice exposed to particulate air pollution in an urban/industrial location. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008; doi:10.1073/pnas.0705896105.

Gao H, Ma MQ, Zhou L, Jia RP, Chen XG, Hu ZD. Interaction of DNA with aromatic hydrocarbons fraction in atmospheric particulates of Xigu District of Lanzhou, China. J Environ Sci (China). 2007;19:948–54.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, Group P-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015; doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Foster WG, Neal MS, Han MS, Dominguez MM. Environmental contaminants and human infertility: hypothesis or cause for concern? Journal of toxicology and environmental health part B. Critical reviews. 2008; doi:10.1080/10937400701873274.

Frutos V, Gonzalez-Comadran M, Sola I, Jacquemin B, Carreras R, Checa Vizcaino MA. Impact of air pollution on fertility: a systematic review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015; doi:10.3109/09513590.2014.958992.

Mohallem SV, de Araujo Lobo DJ, Pesquero CR, Assuncao JV, de Andre PA, Saldiva PH, Dolhnikoff M. Decreased fertility in mice exposed to environmental air pollution in the city of Sao Paulo. Environl Res. 2005; doi:10.1016/j.envres.2004.08.007.

Veras MM, Damaceno-Rodrigues NR, Guimaraes Silva RM, Scoriza JN, Saldiva PH, Caldini EG, Dolhnikoff M. Chronic exposure to fine particulate matter emitted by traffic affects reproductive and fetal outcomes in mice. Environ Res. 2009; doi:10.1016/j.envres.2009.03.006.

Dejmek J, Jelinek R, Solansky I, Benes I, Sram RJ. Fecundability and parental exposure to ambient sulfur dioxide. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:647–54.

Slama R, Bottagisi S, Solansky I, Lepeule J, Giorgis-Allemand L, Sram R. Short-term impact of atmospheric pollution on fecundability. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass). 2013; doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182a702c5.

Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Basagana X, Dadvand P, Martinez D, Cirach M, Beelen R, Jacquemin B. Air pollution and human fertility rates. Environ Int. 2014; doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.05.005.

Mahalingaiah S, Hart JE, Laden F, Farland LV, Hewlett MM, Chavarro J, Aschengrau A, Missmer SA. Adult air pollution exposure and risk of infertility in the Nurses' health study II. Human Reprod (Oxford, England). 2016; doi:10.1093/humrep/dev330.

Younglai EV, Holloway AC, Foster WG. Environmental and occupational factors affecting fertility and IVF success. Human Reprod Update. 2005; doi:10.1093/humupd/dmh055.

Legro RS, Sauer MV, Mottla GL, Richter KS, Li X, Dodson WC, Liao D. Effect of air quality on assisted human reproduction. Human Reprod (Oxford, England). 2010; doi:10.1093/humrep/deq021.

Perin PM, Maluf M, Czeresnia CE, Januario DA, Saldiva PH. Impact of short-term preconceptional exposure to particulate air pollution on treatment outcome in couples undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF/ET). J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010; doi:10.1007/s10815-010-9419-2.

Perin PM, Maluf M, Czeresnia CE, Nicolosi Foltran Januario DA, Nascimento Saldiva PH. Effects of exposure to high levels of particulate air pollution during the follicular phase of the conception cycle on pregnancy outcome in couples undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2010; doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.06.031.

Maluf M, Perin PM, Foltran Januario DA, Nascimento Saldiva PH. In vitro fertilization, embryo development, and cell lineage segregation after pre- and/or postnatal exposure of female mice to ambient fine particulate matter. Fertil Steril. 2009; doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.081.

Lane M, Gardner DK. Ammonium induces aberrant blastocyst differentiation, metabolism, pH regulation, gene expression and subsequently alters fetal development in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2003; doi:10.1095/biolreprod.103.018093.

Burkus J, Kacmarova M, Kubandova J, Kokosova N, Fabianova K, Fabian D, Koppel J, Cikos S. Stress exposure during the preimplantation period affects blastocyst lineages and offspring development. J Reprod Develop. 2015; doi:10.1262/jrd.2015-012.

Minasi MG, Colasante A, Riccio T, Ruberti A, Casciani V, Scarselli F, Spinella F, Fiorentino F, Varricchio MT, Greco E. Correlation between aneuploidy, standard morphology evaluation and morphokinetic development in 1730 biopsied blastocysts: a consecutive case series study. Human Reprod (Oxford, England). 2016; doi:10.1093/humrep/dew183.

Irani M, Reichman D, Robles A, Melnick A, Davis O, Zaninovic N, Xu K, Rosenwaks Z. Morphologic grading of euploid blastocysts influences implantation and ongoing pregnancy rates. Fertil Steril. 2017; doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.11.012.

Januario DA, Perin PM, Maluf M, Lichtenfels AJ, Nascimento Saldiva PH. Biological effects and dose-response assessment of diesel exhaust particles on in vitro early embryo development in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2010; doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq165.

Yoshida S, Sagai M, Oshio S, Umeda T, Ihara T, Sugamata M, Sugawara I, Takeda K. Exposure to diesel exhaust affects the male reproductive system of mice. Int J Androl. 1999;22:307–15.

Watanabe N. Decreased number of sperms and Sertoli cells in mature rats exposed to diesel exhaust as fetuses. Toxicol Lett. 2005; doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.08.010.

Ieradi LA, Cristaldi M, Mascanzoni D, Cardarelli E, Grossi R, Campanella L. Genetic damage in urban mice exposed to traffic pollution. Environ Pollut. 1996:323–8.

Jeng HA, Yu L. Alteration of sperm quality and hormone levels by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on airborne particulate particles. J Environ Sci Health Part A, Toxic/hazardous Subst Environ Engin. 2008; doi:10.1080/10934520801959815.

Watanabe N, Oonuki Y. Inhalation of diesel engine exhaust affects spermatogenesis in growing male rats. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:539–44.

Somers CM, Yauk CL, White PA, Parfett CL, Quinn JS. Air pollution induces heritable DNA mutations. Proc National Academy Sci United States Am. 2002; doi:10.1073/pnas.252499499.

Somers CM, McCarry BE, Malek F, Quinn JS. Reduction of particulate air pollution lowers the risk of heritable mutations in mice. Science. 2004; doi:10.1126/science.1095815.

Inyang F, Ramesh A, Kopsombut P, Niaz MS, Hood DB, Nyanda AM, Archibong AE. Disruption of testicular steroidogenesis and epididymal function by inhaled benzo (a) pyrene. Reprod Toxicol (Elmsford, NY). 2003;17:527–37.

Tsukue N, Toda N, Tsubone H, Sagai M, Jin WZ, Watanabe G, Taya K, Birumachi J, Suzuki AK. Diesel exhaust (DE) affects the regulation of testicular function in male Fischer 344 rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2001; doi:10.1080/15287390151126441.

Rolland M, Le Moal J, Wagner V, Royere D, De Mouzon J. Decline in semen concentration and morphology in a sample of 26,609 men close to general population between 1989 and 2005 in France. Human Reprod (Oxford, England). 2013; doi:10.1093/humrep/des415.

Auger J, Kunstmann JM, Czyglik F, Jouannet P. Decline in semen quality among fertile men in Paris during the past 20 years. N Engl J Med. 1995; doi:10.1056/NEJM199502023320501.

De Rosa M, Zarrilli S, Paesano L, Carbone U, Boggia B, Petretta M, Maisto A, Cimmino F, Puca G, Colao A, et al. Traffic pollutants affect fertility in men. Human Reprod (Oxford, England). 2003;18:1055–61.

Jurewicz J, Hanke W, Radwan M, Bonde JP. Environmental factors and semen quality. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2009; doi:10.2478/v10001-009-0036-1.

Deng Z, Chen F, Zhang M, Lan L, Qiao Z, Cui Y, An J, Wang N, Fan Z, Zhao X, et al. Association between air pollution and sperm quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Pollut. 2016; doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2015.10.044.

Guven A, Kayikci A, Cam K, Arbak P, Balbay O, Cam M. Alterations in semen parameters of toll collectors working at motorways: does diesel exposure induce detrimental effects on semen? Andrologia. 2008; doi:10.1111/j.1439-0272.2008.00867.x.

Hammoud A, Carrell DT, Gibson M, Sanderson M, Parker-Jones K, Peterson CM. Decreased sperm motility is associated with air pollution in salt Lake City. Fertil Steril. 2010; doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.089.

Selevan SG, Borkovec L, Slott VL, Zudova Z, Rubes J, Evenson DP, Perreault SD. Semen quality and reproductive health of young Czech men exposed to seasonal air pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:887–94.

Somers CM. Ambient air pollution exposure and damage to male gametes: human studies and in situ 'sentinel' animal experiments. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2011; doi:10.3109/19396368.2010.500440.

Sram R. Impact of air pollution on reproductive health. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:A542–3.

Wijesekara GU, Fernando DM, Wijerathna S, Bandara N. Environmental and occupational exposures as a cause of male infertility. Ceylon Med J. 2015; doi:10.4038/cmj.v60i2.7090.

Figa-Talamanca I, Cini C, Varricchio GC, Dondero F, Gandini L, Lenzi A, Lombardo F, Angelucci L, Di Grezia R, Patacchioli FR. Effects of prolonged autovehicle driving on male reproduction function: a study among taxi drivers. Am J Ind Med. 1996; doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199612)30:6<750::AID-AJIM12>3.0.CO;2-1.

Hansen C, Luben TJ, Sacks JD, Olshan A, Jeffay S, Strader L, Perreault SD. The effect of ambient air pollution on sperm quality. Environ Health Perspect. 2010; doi:10.1289/ehp.0901022.

Hsu PC, Chen IY, Pan CH, Wu KY, Pan MH, Chen JR, Chen CJ, Chang-Chien GP, Hsu CH, Liu CS, et al. Sperm DNA damage correlates with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons biomarker in coke-oven workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2006; doi:10.1007/s00420-005-0066-3.

Radwan M, Jurewicz J, Polanska K, Sobala W, Radwan P, Bochenek M, Hanke W. Exposure to ambient air pollution-does it affect semen quality and the level of reproductive hormones? Ann Hum Biol. 2016; doi:10.3109/03014460.2015.1013986.

Sokol RZ, Kraft P, Fowler IM, Mamet R, Kim E, Berhane KT. Exposure to environmental ozone alters semen quality. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:360–5.

Rubes J, Selevan SG, Evenson DP, Zudova D, Vozdova M, Zudova Z, Robbins WA, Perreault SD. Episodic air pollution is associated with increased DNA fragmentation in human sperm without other changes in semen quality. Human Reprod (Oxford, England). 2005; doi:10.1093/humrep/dei122.

Evenson DP, Wixon R. Environmental toxicants cause sperm DNA fragmentation as detected by the sperm chromatin structure assay (SCSA). Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005; doi:10.1016/j.taap.2005.03.021.

Jurewicz J, Radwan M, Sobala W, Polanska K, Radwan P, Jakubowski L, Ulanska A, Hanke W. The relationship between exposure to air pollution and sperm disomy. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2015; doi:10.1002/em.21883.

Ogliari KS, Lichtenfels AJ, de Marchi MR, Ferreira AT, Dolhnikoff M, Saldiva PH. Intrauterine exposure to diesel exhaust diminishes adult ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2013; doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.103.

Thurston SW, Ryan L, Christiani DC, Snow R, Carlson J, You L, Cui S, Ma G, Wang L, Huang Y, et al. Petrochemical exposure and menstrual disturbances. Am J Indust Med. 2000;38:555–64.

Cho SI, Damokosh AI, Ryan LM, Chen D, Hu YA, Smith TJ, Christiani DC, Xu X. Effects of exposure to organic solvents on menstrual cycle length. J Occup Environ Med. 2001;43:567–75.

Tomei G, Ciarrocca M, Fortunato BR, Capozzella A, Rosati MV, Cerratti D, Tomao E, Anzelmo V, Monti C, Tomei F. Exposure to traffic pollutants and effects on 17-beta-estradiol (E2) in female workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2006; doi:10.1007/s00420-006-0105-8.

De Coster S, van Larebeke N. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: associated disorders and mechanisms of action. J Environ Public Health. 2012; doi:10.1155/2012/713696.

Kampa M, Castanas E. Human health effects of air pollution. Environ Pollut. 2008; doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.012.

Han Y, Xia Y, Zhu P, Qiao S, Zhao R, Jin N, Wang S, Song L, Fu G, Wang X. Reproductive hormones in relation to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) metabolites among non-occupational exposure of males. Sci Total Environ. 2010; doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.11.021.

Taneda S, Hayashi H, Sakata M, Yoshino S, Suzuki A, Sagai M, Mori Y. Anti-estrogenic activity of diesel exhaust particles. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:1477–80.

Oh SM, Ryu BT, Chung KH. Identification of estrogenic and antiestrogenic activities of respirable diesel exhaust particles by bioassay-directed fractionation. Arch Pharm Res. 2008:75–82.

Noguchi K, Toriba A, Chung SW, Kizu R, Hayakawa K. Identification of estrogenic/anti-estrogenic compounds in diesel exhaust particulate extract. Biomed Chromatogr. 2007; doi:10.1002/bmc.861.

Yoshida S, Hirano S, Shikagawa K, Hirata S, Rokuta S, Takano H, Ichinose T, Takeda K. Diesel exhaust particles suppress expression of sex steroid hormone receptors in TM3 mouse Leydig cells. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007; doi:10.1016/j.etap.2007.07.003.

Meek MD. Ah receptor and estrogen receptor-dependent modulation of gene expression by extracts of diesel exhaust particles. Environ Res. 1998; doi:10.1006/enrs.1998.3870.

Misaki K, Suzuki M, Nakamura M, Handa H, Iida M, Kato T, Matsui S, Matsuda T. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and estrogen receptor ligand activity of organic extracts from road dust and diesel exhaust particulates. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2008; doi:10.1007/s00244-007-9110-5.

Owens CV Jr, Lambright C, Cardon M, Gray LE Jr, Gullett BK, Wilson VS. Detection of androgenic activity in emissions from diesel fuel and biomass combustion. Environ Toxicol Chem / SETAC. 2006;25:2123–31.

Barouki R, Aggerbeck M, Aggerbeck L, Coumoul X. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor system. Drug Metabol Drug Interact. 2012; doi:10.1515/dmdi-2011-0035.

Beischlag TV, Luis Morales J, Hollingshead BD, Perdew GH. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2008;18:207–50.

Mesquita SR, van Drooge BL, Oliveira E, Grimalt JO, Barata C, Vieira N, Guimaraes L, Pina B. Differential embryotoxicity of the organic pollutants in rural and urban air particles. Environ Pollut. 2015; doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2015.08.008.

Zhang H, Yao Y, Chen Y, Yue C, Chen J, Tong J, Jiang Y, Chen T. Crosstalk between AhR and wnt/beta-catenin signal pathways in the cardiac developmental toxicity of PM2.5 in zebrafish embryos. Toxicology. 2016; doi:10.1016/j.tox.2016.05.014.

Izawa H, Kohara M, Watanabe G, Taya K, Sagai M. Diesel exhaust particle toxicity on spermatogenesis in the mouse is aryl hydrocarbon receptor dependent. J Reprod develop. 2007;53:1069–78.

Izawa H, Kohara M, Watanabe G, Taya K, Sagai M. Effects of diesel exhaust particles on the male reproductive system in strains of mice with different aryl hydrocarbon receptor responsiveness. J Reprod Develop. 2007;53:1191–7.

Hernandez-Ochoa I, Karman BN, Flaws JA. The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the female reproductive system. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009; doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2008.09.037.

Shanle EK, Xu W. Endocrine disrupting chemicals targeting estrogen receptor signaling: identification and mechanisms of action. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011; doi:10.1021/tx100231n.

Agarwal A, Allamaneni SS. Free radicals and male reproduction. J Indian Med Assoc. 2011;109:184–7.

Agarwal A, Sharma RK, Nallella KP, Thomas AJ Jr, Alvarez JG, Sikka SC. Reactive oxygen species as an independent marker of male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2006; doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.111.

Agarwal A, Virk G, Ong C, du Plessis SS. Effect of oxidative stress on male reproduction. World J Mens Health. 2014; doi:10.5534/wjmh.2014.32.1.1.

Muratori M, Tamburrino L, Marchiani S, Cambi M, Olivito B, Azzari C, Forti G, Baldi E. Investigation on the origin of sperm DNA fragmentation: role of apoptosis, immaturity and oxidative stress. Mol Med. 2015; doi:10.2119/molmed.2014.00158.

Tvrda E, Knazicka Z, Bardos L, Massanyi P, Lukac N. Impact of oxidative stress on male fertility - a review. Acta Vet Hung. 2011; doi:10.1556/AVet.2011.034.

Walczak-Jedrzejowska R, Wolski JK, Slowikowska-Hilczer J. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in male fertility. Cent European J Urol. 2013; doi:10.5173/ceju.2013.01.art19.

Agarwal A, Aponte-Mellado A, Premkumar BJ, Shaman A, Gupta S. The effects of oxidative stress on female reproduction: a review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol : RB&E. 2012; doi:10.1186/1477-7827-10-49.

Ruder EH, Hartman TJ, Blumberg J, Goldman MB. Oxidative stress and antioxidants: exposure and impact on female fertility. Human Reprod Update. 2008; doi:10.1093/humupd/dmn011.

Lim J, Nakamura BN, Mohar I, Kavanagh TJ, Luderer U. Glutamate Cysteine Ligase modifier subunit (Gclm) null mice have increased ovarian oxidative stress and accelerated age-related ovarian failure. Endocrinol. 2015; doi:10.1210/en.2015-1206.

Barth A, Brucker N, Moro AM, Nascimento S, Goethel G, Souto C, Fracasso R, Sauer E, Altknecht L, da Costa B, et al. Association between inflammation processes, DNA damage, and exposure to environmental pollutants. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016; doi:10.1007/s11356-016-7772-0.

Walton RT, Mudway IS, Dundas I, Marlin N, Koh LC, Aitlhadj L, Vulliamy T, Jamaludin JB, Wood HE, Barratt BM, et al. Air pollution, ethnicity and telomere length in east London schoolchildren: an observational study. Environ Int. 2016; doi:10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.021.

Cao Y. Environmental pollution and DNA methylation: carcinogenesis, clinical significance, and practical applications. Front Med. 2015; doi:10.1007/s11684-015-0406-y.

Lepeule J, Bind MA, Baccarelli AA, Koutrakis P, Tarantini L, Litonjua A, Sparrow D, Vokonas P, Schwartz JD. Epigenetic influences on associations between air pollutants and lung function in elderly men: the normative aging study. Environ Health Perspect. 2014; doi:10.1289/ehp.1206458.

Holloway JW, Savarimuthu Francis S, Fong KM, Yang IA. Genomics and the respiratory effects of air pollution exposure. Respirol. 2012; doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02164.x.

Ding R, Jin Y, Liu X, Zhu Z, Zhang Y, Wang T, Xu Y. Characteristics of DNA methylation changes induced by traffic-related air pollution. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2016; doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2015.12.002.

Byun HM, Barrow TM. Analysis of pollutant-induced changes in mitochondrial DNA methylation. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, NJ). 2015; doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2288-8_19.

Byun HM, Colicino E, Trevisi L, Fan T, Christiani DC, Baccarelli AA. Effects of air pollution and blood mitochondrial DNA Methylation on markers of heart rate variability. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016; doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.003218.

Vecoli C, Montano L, Andreassi MG. Environmental pollutants: genetic damage and epigenetic changes in male germ cells. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016; doi:10.1007/s11356-016-7728-4.

Stouder C, Somm E, Paoloni-Giacobino A. Prenatal exposure to ethanol: a specific effect on the H19 gene in sperm. Reprod Toxicol. 2011; doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.02.009.

Park CJ, Nah WH, Lee JE, Oh YS, Gye MC. Butyl paraben-induced changes in DNA methylation in rat epididymal spermatozoa. Andrologia. 2012; doi:10.1111/j.1439-0272.2011.01162.x.

Tsamou M, Vrijens K, Madhloum N, Lefebvre W, Vanpoucke C, Nawrot TS. Air pollution-induced placental epigenetic alterations in early life: a candidate miRNA approach. Epigenetics. 2016; doi:10.1080/15592294.2016.1155012.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement for this manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in reading referenced papers and writing the manuscript. JC; NG, JM and RL have reviewed studies and JP conceived the review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable (review of published papers).

Consent for publication

Not applicable (review of published papers).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Carré, J., Gatimel, N., Moreau, J. et al. Does air pollution play a role in infertility?: a systematic review. Environ Health 16, 82 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0291-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0291-8