Abstract

Discriminatory health systems and inequalities in service provision inevitably create barriers for certain populations in a health emergency. Persons with disabilities have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. They commonly experience three increased risks - of contracting the disease, of severe disease or death, and of new or worsening health conditions. These added risks occur due to a range of barriers in the health sector, including physical barriers that prevent access to health facilities and specific interventions; informational barriers that prevent access to health information and/or reduce health literacy; and attitudinal barriers which give rise to stigma and exclusion, all of which add to discrimination and inequality. Furthermore, national health emergency preparedness and planning may fail to consider the needs and priorities of persons with disabilities, in all their diversity, thus leaving them behind in responses. This commentary discusses the importance of inclusive health systems strengthening as a prerequisite for accessible and comprehensive health emergency preparedness and response plans that reach everyone. Lessons learned relating to disability inclusion in the COVID-19 pandemic can inform health systems strengthening in recovery efforts, addressing underlying barriers to access and inclusion, and in turn improving preparedness for future health emergencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Sustainable Development Goals set forth global commitments to achieve universal health coverage. Health systems strengthening is seen as a central vehicle for progressing universal health coverage, with equity and inclusion recognized as “intermediary objectives” in most national health policies, plans and strategies [1]. Essential health service coverage and public health interventions improve the overall health status of affected populations, contributing to the prevention of outbreaks, mitigating risks and building community resilience to such hazards [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, has laid bare the gaps in health systems strengthening efforts, and in turn preparedness for and resilience to health emergencies. The 2021 Sustainable Development Goals Report documents how progress towards health goals has been derailed, with 90% of countries reporting ongoing disruptions to essential health services and exacerbation of health inequalities [3]. There is also a growing body of evidence to demonstrate that COVID-19 disproportionately affects marginalized groups who face intersecting forms of discrimination based on age, gender, disability, ethnicity, or race, among other factors [4]. As such, inclusive health systems strengthening is a prerequisite for inclusive health emergency preparedness and response plans that reach everyone.

Disability is part of being human. Everybody is likely to experience difficulties in functioning at some point in their lives, particularly when growing older. According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), disability is an umbrella term which describes how health conditions and impairments, in combination with a range of environmental and personal factors, can restrict the participation and activities of an individual in their community [5]. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) further describes persons with disabilities as “those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” [6].

Even outside of times of crisis, persons with disabilities experience health inequities driven by unjust or unfair conditions, such as stigma and discrimination, poverty and poor living conditions, exclusion from education and employment, and barriers in accessing quality healthcare. For example, 37% of premature deaths among persons with intellectual disabilities have been linked to poor quality care compared to only 13% in the general population [7]. With an estimated 15% of the world’s population experiencing disability [8], efforts toward universal health coverage, promoting healthier populations, and ensuring protection in health emergencies will only be effective if the needs, priorities and contributions of persons with disabilities are considered.

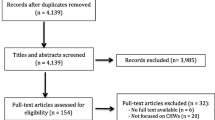

This commentary will explore how lessons learned relating to disability inclusion in the COVID-19 pandemic can inform health systems strengthening, addressing underlying barriers to access and inclusion, and in turn improving preparedness and response in future health emergencies. It draws on preliminary findings relating to COVID-19 from a scoping review on disability inclusion in health emergencies being conducted for the upcoming Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities by the World Health Organization. A total of 569 papers were identified through searches of academic databases, of which 242 were included in the wider health emergencies scoping review – 209 focused on the COVID-19 pandemic. Papers were included if they discussed key concepts relating to the impact of health emergencies on persons with disabilities, barriers to access and inclusion in emergency responses, and strategies to promote disability inclusion in these responses. Papers published over 10 years ago, as well as articles, conference abstracts and editorials which did not present substantial evidence relating to the experiences of persons with disabilities were excluded. While academic searches included all languages and countries, most papers which met inclusion criteria were in English (203 in English, four in Spanish, one in Russian and one in Portuguese) and presented research from high-income contexts. The academic literature search was supplemented with a search of grey literature, bringing forth another 85 publications relating to disability inclusion in the COVID-19 pandemic, including health emergency response plans, organizational research reports and recommendations from organizations of persons with disabilities.

How are persons with disabilities affected by the COVID-19 pandemic?

There is evidence that persons with disabilities are disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. First, persons with disabilities may be at greater risk of contracting COVID-19 due to difficulties in maintaining physical distancing, implementing hygiene measures, and inaccessible public health information [9, 10]. While evidence of COVID-19 infection risk among the wider population of persons with disabilities is still inconclusive [11], some studies have found infection rates to be 4–5 times higher among those living in residential or long-term care facilities compared with the general population [12]. Furthermore, persons with disabilities living in low- and middle-income countries [9], and those living in humanitarian contexts [13] may lack access to appropriate water, sanitation and hygiene facilities and materials (e.g., water, soap, hand sanitizer), as well as personal protective equipment, such as masks.

Second, persons with disabilities have an increased risk of severe disease or death when infected due to potential underlying health conditions, and barriers in accessing appropriate and timely healthcare.Footnote 1 Excess risk is more marked among women than men with disabilities [14] and persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities [15,16,17,18,19]. Evidence from the UK indicates that persons with intellectual disabilities are 4–5 times more likely to be admitted to hospital, and up to 8 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than those without an intellectual disability [16]. This group also faces greater risk at younger ages [15, 19, 20], and when living in residential facilities [15, 21]. Initial studies, again from the UK, also suggest that persons with intellectual disabilities are less likely to receive critical care interventions, despite having more severe symptoms on admission and similar rates of complications as COVID-19 patients without disabilities [22], raising concerns about discriminatory triage processes and unconscious bias among medical staff.

Third, persons with disabilities may face new or worsening health conditions as lockdowns, physical distancing requirements and prioritization of health services disrupt access to regular health check-ups, medication, assistive devices, psychosocial support, rehabilitation [9, 23, 24], as well as assistant and home support services [25], which are critical to their independence and autonomy. COVID-19 and the public health measures enacted have also added to the psychosocial stress experienced by persons with disabilities [9, 15, 23, 26,27,28], and there is a growing body of evidence about how isolation due to physical distancing and movement restrictions has exacerbated the risk of violence against persons with disabilities [9, 23, 29], especially women, girls, transgender and non-binary persons with disabilities [30, 31]. Lastly, already more likely to live in poverty [32], persons with disabilities are facing job losses, reduced household income, and in some countries, food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic [9, 24, 33], with some studies demonstrating greater economic impacts compared to those without disabilities [9, 23, 34, 35] – all of which are determinants of health and well-being.

How is disability inclusion considered in COVID-19 responses?

A range of strategies have been employed to promote disability inclusion in national COVID-19 responses. However, there is a lack of data and information on the outcomes of such strategies, who they reach and don’t reach, and their effectiveness. One of the most common approaches referenced in the literature is the production of public health information in multiple formats, including Easy-to-Read publications; the addition of audio descriptors, sign language and captions to audio-visual materials; and screen-reader accessible formats [36,37,38,39]. However, there are still gaps in ensuring these accessible materials are also available in multiple languages [36].

COVID-19 guidelines for persons with disabilities have been developed at a global level [13, 40,41,42,43] and in some countries [44,45,46,47]. However, they often fail to fully reflect the diversity of needs in the population of persons with disabilities; address the intersecting disadvantage faced due to gender, age or socioeconomic status; or include a plan for implementation and monitoring [47, 48].

There are examples of existing or new coordination mechanisms, which usually include a range of stakeholders, advising on and supporting disability inclusion in COVID-19 responses. For example, in Saudi Arabia and Jordan, already established mechanisms to support coordination between government bodies and non-governmental organizations, including organizations of persons with disabilities, played a role in: 1. Developing comprehensive communication strategies for persons with disabilities and their families about COVID-19 (e.g., educational channels on YouTube and seminars targeting persons with disabilities and their families with COVID-19 prevention information); 2. Engaging with Ministries of Health on disability inclusion (e.g., “issuing directives” on healthcare for persons with disabilities in Jordan, although specific details are lacking; and providing health reports in sign language in Saudi Arabia); and, 3. Adapting distance education approaches to ensure accessibility and reasonable accommodation for persons with disabilities (e.g., the adaptation of education curricula, examinations, and computerized educational programs) [49]. Similarly, in China there are reports of strengthening the “committee system of persons with disabilities”, as well as launching the “remote interactive decision-making system” whereby persons with disabilities can raise problems and difficulties directly with authorities and are consulted on solution development [50]. Non-governmental organizations and civil society have played a critical role identifying the injustices faced by persons with disabilities and influencing governments to act accordingly. One such example comes from the UK where voluntary organizations and care-givers challenged the use of the Clinical Frailty ScaleFootnote 2 to assess COVID-19 patients for escalation of medical treatment, because biased implementation may disadvantage persons with intellectual disabilities (among other groups) [51] – this directly led to the updating of clinical guidelines [52].

What are the gaps and opportunities to strengthen inclusion and equity in COVID-19 responses?

There are three priority areas where strengthening disability inclusion in COVID-19 responses and health systems strengthening intersect – 1. Data collection and analysis of health inequities among persons with disabilities; 2. Equitable access to new modalities and innovations, such as telehealth, which in turn increases access to information as well as wider healthcare services in an emergency; and 3. Inclusive decision-making processes – all of which would contribute to improved equity, accountability, and resilience of health systems before, during and after crises.

Expanding on the first area relating to data, there is a distinct gap in empirical evidence on the health inequities faced by persons with disabilities in low- to middle-income countries in the COVID-19 pandemic, and a need to strengthen disability data collection and analysis, not only to inform health emergency policies and programs, but also to feed into health systems strengthening efforts. For example, the Coronavirus Disability Survey (COV-DIS) has been used in the USA to assesses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on persons with disabilities in domains of general and psychological health, activities of daily living, financial resources, and information and transportation access [53, 54], with some authors suggesting that it “could help improve the evidence for ongoing response and recovery during this emergency” [9]. However, a more inclusive and intersectional approach could be to include disability as one of many variables considered in health emergency data collection, allowing for disaggregated analysis of the risks factors faced by different groups and informing responses accordingly [11]. These initiatives should link to existing health information and service data systems, including government health insurance schemes, to provide more comprehensive analyses of health equity [55] (Table 1).

Secondly, the COVID-19 pandemic has indirectly advanced the use of digital technology in all facets of life, including health, work, education, and social connection – these new practices and ways of working are likely to continue far beyond the COVID-19 crisis and will no doubt be a cornerstone in future pandemic responses. The increased uptake of telehealth has been suggested to provide “long-awaited opportunities for people with disabilities to receive evidence-based health care comfortably in their own homes” [60]. However, a range of intersectional factors, such as gender, age, socioeconomic status, and type of impairment (among others) makes this means that not all persons with disabilities benefit equally from these advancements. For example, in low- and middle-income countries this modality is less accessible, with low digital literacy, reduced access to devices, and poor and / or costly internet connections [9]. It is critical to upscale efforts to address the “digital divide” faced by different groups, including persons with disabilities [9, 61], women and girls [62], and those living in displacement and resource limited settings [63], not only to ensure equitable access to health services, but also to address structural inequality and the social determinants health. There are calls for a range of diverse persons with disabilities, including those with intellectual disabilities, to be directly involved in research into adaptive technology, so that we can learn more about their preferences, and what is most effective in terms of capacity development and implementation [51].

Third, inclusive decision-making systems are critical to effective pandemic prevention and guaranteeing the rights of persons with disabilities in pandemic responses [64]. Given the complexity of analysis and the diversity of strategies required, it is important to adopt “people-centered approaches” whereby persons with disabilities, family members, support services and health care providers play a central role in health emergency planning, working together to fully understand the consequences of proposed public health interventions and identify the needs of individuals with disabilities when implemented. Such an approach has the potential to better address both the direct and indirect impact of COVID-19 on persons with disabilities and can bring forth contextualized solutions which address environmental, personal and participation factors [65].

Addressing these gaps at a systems level, Jesus and colleagues [66] propose the PREparedness, RESponse and SySTemic transformation (PRE-RE-SyST) model with four levels of strategic action (including “simple rules”) to systematically integrate disability into health emergency preparedness and response: 1. Respond to prevent or reduce inequalities related to disability during a pandemic crisis; 2. Prepare ahead for pandemic and other crises responses; 3. Design systems and policies for a structural disability-inclusiveness; and, 4. Transform society’s cultural assumptions about disability. While this model is largely based on literature from high-income countries, it may serve as a starting point to guide governments, policymakers, and other stakeholders on disability-inclusive pandemic response planning, through health systems strengthening and by addressing social determinants and structural inequalities in the health sector.

Conclusions

In a health emergency, such as that related to COVID-19, actions to reduce infection, morbidity, and mortality due to the virus, may concurrently add new health risks and needs for different groups, such as persons with disabilities. People-centered approaches can support inclusive decision-making at multiple levels and are a vehicle to ensure that health emergency responses meet the needs of diverse groups, including sub-populations who may face added vulnerability, in the affected community. Health emergency programming needs to not only prevent, recognize and respond to disability disparities during a crisis, it also needs to address structural inequalities and transform cultural assumptions about disability, especially in preparedness and recovery efforts. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought forth an unprecedented engagement from the disability community in a health emergency – there is a wealth of experience and perspectives among persons with disabilities and their representative organizations that can and should be drawn on in knowledge-generation and policy development in health systems strengthening for effective health emergency responses.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Notes

Studies of mortality and morbidity among persons with disabilities infected with COVID-19 are mostly from high-income countries, such as the UK, USA, and Canada.

A study by Festen and colleagues (2021) has demonstrated that the Clinical Frailty Scale incorrectly classified 74.9% of patients with intellectual disabilities as being too frail to have a good probability of survival. Source: Festen D, Josje S, Hilgenkamp T, Oppewal A. Determining frailty in people with intellectual disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2021;34(5):1314–5.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- CRPD:

-

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- FDD11:

-

Functioning and Disability Disaggregation Tool

- ICF:

-

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

- MDS:

-

Model Disability Survey

- PRE-RE-SyST:

-

PREparedness, RESponse and SySTemic transformation model

- WHO-DAS II:

-

WHO Disability Assessment Schedule II

References

Kieny MP, Bekedam H, Dovlo D, Fitzgerald J, Habicht J, Harrison G, et al. Strengthening health systems for universal health coverage and sustainable development. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(7):537–9.

World Health Organization. Health emergency and disaster risk management framework. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. https://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/preparedness/health-emergency-and-disaster-risk-management-framework-eng.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2022.

United Nations. Sustainable development goals report 2021. New York: United Nations; 2021. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2021.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2022.

Paremoer L, Nandi S, Serag H, Baum F. COVID-19 pandemic and the social determinants of health. BMJ. 2021;372:n129.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organziation; 2001. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42407. Accessed 26 Jan 2022.

UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: resolution adopted by the general assembly, 24 January 2007, A/RES/61/106. New York: United Nations; 2007. https://www.refworld.org/docid/45f973632.html. Accessed 26 Jan 2022.

Heslop P, Blair PS, Fleming P, Hoghton M, Marriott A, Russ L. The confidential inquiry into premature deaths of people with intellectual disabilities in the UK: a population-based study. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):889–95.

World Health Organization & World Bank. World report on disability. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44575. Accessed 26 Jan 2022.

Hillgrove T, Blyth J, Kiefel-Johnson F, Pryor W. A synthesis of findings from ‘rapid assessments’ of disability and the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for response and disability-inclusive data collection. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):15.

Yap J, Chaudhry V, Jha CK, Mani S, Mitra S. Are responses to the pandemic inclusive? A rapid virtual audit of COVID-19 press briefings in LMICs. World Dev. 2020;136:105122.

Gupta A, Kavanagh A, Disney G. The impact of and government planning and responses to pandemics for people with disability: a rapid review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):16.

Kamalakannan S, Bhattacharjya S, Bogdanova Y, Papadimitriou C, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Bentley J, et al. Health risks and consequences of a COVID-19 infection for people with disabilities: scoping review and descriptive thematic analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8).

Reference Group on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities. COVID-19 response: key messages on applying the IASC guidelines on inclusion of persons with disabilities in humanitarian action. Geneva: Inter-Agency Standing Committee; 2020. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2020-11/IASC%20Key%20Messages%20on%20Applying%20IASC%20Guidelines%20on%20Disability%20in%20the%20COVID-19%20Response%20%28final%20version%29.pdf. Accessed 9 Dec 2021.

Bosworth ML, Ayoubkhani D, Nafilyan V, Foubert J, Glickman M, Davey C, et al. Deaths involving COVID-19 by self-reported disability status during the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in England: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(11):e817–e25.

Doody O, Keenan PM. The reported effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with intellectual disability and their carers: a scoping review. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):786–804.

Williamson EJ, McDonald HI, Bhaskaran K, Walker AJ, Bacon S, Davy S, et al. Risks of COVID-19 hospital admission and death for people with learning disability: population based cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. BMJ. 2021;374:n1592.

Das-Munshi J, Chang CK, Bakolis I, Broadbent M, Dregan A, Hotopf M, et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality in people with mental disorders and intellectual disabilities, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;11:100228.

Lunsky Y, Durbin A, Balogh R, Lin E, Palma L, Plumptre L. COVID-19 positivity rates, hospitalizations and mortality of adults with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities in Ontario, Canada. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(1):101174.

Turk MA, Landes SD, Formica MK, Goss KD. Intellectual and developmental disability and COVID-19 case-fatality trends: TriNetX analysis. Disabil Health J. 2020;13(3):100942.

Heslop P, Byrne V, Calkin R, Huxor A, Sadoo A, Sullivan B. Deaths of people with intellectual disabilities: analysis of deaths in England from COVID-19 and other causes. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(6):1630–40.

Landes SD, Turk MA, Ervin DA. COVID-19 case-fatality disparities among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: evidence from 12 US jurisdictions. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(4):101116.

Baksh RA, Pape SE, Smith J, Strydom A. Understanding inequalities in COVID-19 outcomes following hospital admission for people with intellectual disability compared to the general population: a matched cohort study in the UK. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):e052482.

Jesus TS, Bhattacharjya S, Papadimitriou C, Bogdanova Y, Bentley J, Arango-Lasprilla JC, et al. Lockdown-related disparities experienced by people with disabilities during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: scoping review with thematic analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6178.

Hearst MO, Hughey L, Magoon J, Mubukwanu E, Ndonji M, Ngulube E, et al. Rapid health impact assessment of COVID-19 on families with children with disabilities living in low-income communities in Lusaka, Zambia. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0260486.

Brennan CS. Disability rights during the pandemic: a global report on findings of the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor. COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor; 2020. https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/sites/default/files/disability_rights_during_the_pandemic_report_web_pdf_1.pdf. Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

Lund EM, Forber-Pratt A, J., Wilson C, Mona LR. The COVID-19 pandemic, stress, and trauma in the disability community: a call to action. Rehabil Psychol. 2020;65(4):313–22.

Aishworiya R, Kang YQ. Including children with developmental disabilities in the equation during this COVID-19 pandemic. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(6):2155–8.

Okoro CA, Strine TW, McKnight-Eily L, Verlenden J, Hollis ND. Indicators of poor mental health and stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic, by disability status: a cross-sectional analysis. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(4):101110.

Lund EM. Interpersonal violence against people with disabilities: additional concerns and considerations in the COVID-19 pandemic. Rehabil Psychol. 2020;65(3):199–205.

Women Enabled International. COVID-19 at the intersection of gender and disability: findings of a global human rights survey. Washington D.C.: Women Enabled International; 2020. https://womenenabled.org/wp-content/uploads/Women%20Enabled%20International%20COVID-19%20at%20the%20Intersection%20of%20Gender%20and%20Disability%20May%202020%20Final.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2021.

Pearce E. Research query: disability considerations in GBV programming during the COVID-19 pandemic. London: GBV AOR Helpdesk; 2020. https://www.sddirect.org.uk/media/2086/gbv-aor-hd-covid-19-gbv-disability_updated-28092020.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2022.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. UN flagship report on disability and development 2018: realization of the sustainable development goals by, for and with persons with disabilities. New York: United Nations; 2018. https://social.un.org/publications/UN-Flagship-Report-Disability-Final.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan 2022.

Brucker DL, Stott G, Phillips KG. Food sufficiency and the utilization of free food resources for working-age Americans with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabil Health Journal. 2021;14(4):101153.

Jones M. COVID-19 and the labour market outcomes of disabled people in the UK. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114637.

Emerson E, Stancliffe R, Hatton C, Llewellyn G, King T, Totsika V, et al. The impact of disability on employment and financial security following the outbreak of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. J Public Health. 2021;43(3):472–8.

Colon-Cabrera DS, Shivika; Warren, Narelle; Sakellariou, Dikaios. Examining the role of governmsent in shaping disability inclusiveness around COVID-19: a framework analysis of Australian guidelines. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):166.

Kavanagh A, Dickinson H, Carey G, Llewellyn G, Emerson E, Disney G, et al. Improving health care for disabled people in COVID-19 and beyond: lessons from Australia and England. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(2):101050.

Metintas S. COVID-19: infection control strategy and public health awareness for disabled individuals in Turkey. Erciyes Med J. 2021;43(4):315–7.

Kuper H, Banks LM, Bright T, Davey C, Shakespeare T. Disability-inclusive COVID-19 response: what it is, why it is important and what we can learn from the United Kingdom's response. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:79.

International Disability Alliance. Toward a disability-inclusive COVID19 response: 10 recommendations from the international disability Alliance. 2020. https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/sites/default/files/ida_recommendations_for_disability-inclusive_covid19_response_final.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2022.

World Health Organization. Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Disability-2020-1. Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

UNICEF. COVID-19 response: considerations for children and adults with disabilities. New York: UNICEF; 2020. https://sites.unicef.org/disabilities/files/COVID-19_response_considerations_for_people_with_disabilities_190320.pdf. Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

United Nations. Policy brief: a disability-inclusive response to COVID-19. New York: United Nations; 2020. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_on_persons_with_disabilities_final.pdf. Accessed 6 Dec 2021.

Daegu Solidarity Against Disability Discrimination (SADD). Guideline on hopitalisation of COVID-19 confirmed PWD (translated by the Korean disability forum). Korean Disability Forum; 2020. https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/sites/default/files/guideline_on_hospitalisation_of_covid-19_confirmed_pwd.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2022.

Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities Government of India. Comprehensive disability inclusive guidelines for protection and safety of persons with disabilities (Divyangjan) during COVID 19. 2020. https://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/content/GuidelinesforwelfareofPersonswithDisabilities.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2022.

Zhang SB, Chen Z. China's prevention policy for people with disabilities during the COVID-19 epidemic. Disabil Soc. 2021;36(8):1368–72.

Velasco JV, Obnial JC, Pastrana A, Ang HK, Viacrusis PM, Lucero-Prisno Iii DE. COVID-19 and persons with disabilities in the Philippines: a policy analysis. Health Promot Perspect. 2021;11(3):299–306.

Sakellariou D, Malfitano APS, Rotarou ES. Disability inclusiveness of government responses to COVID-19 in South America: a framework analysis study. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):131.

Al-Zoubi SM, Bakkar BS. Arab prophylactic measures to protect individuals with disabilities from the spread of COVID-19. Int J Spec Educ. 2021;36(1):69–76.

Qi F, Wu Y, Wang Q. Experience and discussion: safeguards for people with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Front Public Health. 2021;9:744706.

Courtenay K, Perera B. COVID-19 and people with intellectual disability: impacts of a pandemic. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(3):231–6.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE updates rapid COVID-19 guideline on critical care, 25 March 2020. London: NICE; 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/news/article/nice-updates-rapid-covid-19-guideline-on-critical-care. Accessed 22 Jan 2022.

Bernard A, Weiss S, Stein JD, Ulin SS, D'Souza C, Salgat A, et al. Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on persons with disabilities: development of a novel survey. Int J Public Health. 2020;65(6):755–7.

Bernard A, Weiss S, Rahman M, Ulin SS, D'Souza C, Salgat A, et al. The impact of COVID-19 and pandemic mitigation measures on persons with sensory impairment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;234:49–58.

Boyle CA, Fox MH, Havercamp SM, Zubler J. The public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic for people with disabilities. Disabil Health Journal. 2020;13(3):100943.

World Health Organization WPR. Disability-inclusive health services toolkit: a resource for health facilities in the Western Pacific region. 2020. https://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/14639/9789290618928-eng.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2022.

Washington Group on Disability Statistics. WG short set on functioning (WG-SS) website. London: UNiversity College London; 2022. https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/question-sets/wg-short-set-on-functioning-wg-ss/. Accessed 10 Feb 2022.

World Health Organization, World Bank. Model disability survey (MDS) - survey manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241512862. Accessed 10 Feb 2022.

Üstün T, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J. Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/measuring-health-and-disability-manual-for-who-disability-assessment-schedule-(-whodas-2.0). Accessed 10 Feb 2022.

Kendall E, Ehrlich C, Chapman K, Shirota C, Allen G, Gall A, et al. Immediate and long-term implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for people with disabilities. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(12):1774–9.

Cho M, Kim KM. Effect of digital divide on people with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabil Health Journal. 2022;15(1):101214.

Bryant J, Holloway K, Lough O, Willitts-King B. Briefing note: bridging humanitarian digital divides during COVID-19. London: Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute; 2020. https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/Bridging_humanitarian_digital_divides_during_Covid-19.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2022.

Casswell J. The digital lives of refugees: how displaced populations use mobile phones and what gets in the way. GSMA; 2019. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/70843.pdf. Accessed 26 Jan 2022.

Qi F, Wang Q. Guaranteeing the health rights of people with disabilities in the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives from China. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:2357–63.

Senjam SS. A persons-centered approach for prevention of COVID-19 disease and its impacts in persons with disabilities. Front Public Health. 2020;8:608958.

Jesus TS, Kamalakannan S, Bhattacharjya S, Bogdanova Y, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Bentley J, et al. PREparedness, REsponse and SySTemic transformation (PRE-RE-SyST): a model for disability-inclusive pandemic responses and systemic disparities reduction derived from a scoping review and thematic analysis. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):204.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of International Journal for Equity in Health Volume 21 Supplement 3, 2022: COVID-19 and inequality. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-21-supplement-3.

Funding

All authors are in roles funded by the World Health Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EP led the scoping review and drafting of this article, with reviews and contributions from KK, DB and AC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

EP is a consultant for the WHO Sensory functions, disability and rehabilitation unit, KK is a technical officer for the WHO Sensory functions, disability and rehabilitation unit, DB is the technical lead for the WHO Sensory functions, disability and rehabilitation unit, AC is the unit head of the WHO Sensory functions, disability and rehabilitation unit.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode), which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. If you remix, transform, or build upon this article or a part thereof, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. In any reproduction of this article there should not be any suggestion that World Health Organisation or this article endorse any specific organization or products. The use of the World Health Organisation logo is not permitted. This notice should be preserved along with the article's original URL.

About this article

Cite this article

Pearce, E., Kamenov, K., Barrett, D. et al. Promoting equity in health emergencies through health systems strengthening: lessons learned from disability inclusion in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Equity Health 21 (Suppl 3), 149 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-022-01766-6

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-022-01766-6