Abstract

Background

Despite the growing number of people with migrant background in Germany, a systematic review about their utilization of health care and differences to the non-migrant population is lacking. By covering various sectors of health care and migrant populations, the review aimed at giving a general overview and identifying special areas of potential intervention.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted in PubMed database including records that were published until 1st of June 2017. Further criteria for eligibility were a publication in a peer-reviewed journal written in English or German language. The studies have to report quantitative and original data of a population residing in Germany. The appropriateness of the studies was judged by both authors. Studies were excluded if native controls were not originated from the same sample. Moreover, indicators of health care utilization have to assess individual behaviour like consultation or participation rates. 63 studies met the inclusion criteria for a qualitative synthesis of the findings.

Results

The overall findings indicate a lower utilization among migrants, although the results vary in terms of health care sector, indicator of health care utilization and migrant population. For specialist care, medication use, therapist consultations and counselling, rehabilitation as well as disease prevention (early cancer detection, prevention programs for children and oral health check-ups) a lower utilization among people with migrant background was found. The lower usage was particularly shown for migrants of the 1st generation, people with two-sided migrant background, children/adolescents and women. Due to the methodological heterogeneity a meta-analysis was not feasible. As most of the studies were cross-sectional, no causal interpretations could be drawn.

Conclusions

The inequalities in utilization could not substantially be explained by differences in the socioeconomic status. Other reasons of lower utilization could be due to differences in need, preferences, information, language and formal access barriers (e.g. charges, waiting times, travel distances or lost wages). Different migrant-specific and migrant-sensitive strategies are relevant to address the problem for certain health care sectors and migrant populations.

Trial registration

The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42014015162).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health and health care among migrants are relevant and controversial issues in Europe since many years [1, 2]. The number of people with migrant status living in Europe is growing rapidly. In Germany, more than 20% of the total population of about 82.4 million people have a migrant background, resulting in about 18.6 million individuals (based on a definition of migrant background to people with foreign nationality, foreign country of birth, or if at least one parent is foreigner or was born abroad) [3]. In this context, health care access and utilization of migrants have become an essential subject [4, 5]. Ethnicity is an important determinant of health care utilization included in the well-established Behavioral Model of Health Services Use by Ronald Andersen [6,7,8]. His conceptual framework distinguishes between predisposing, enabling and need factors of health care use. Ethnicity is a contextual (ethnic and racial composition, spatial segregation) and an individual (nationality, country of origin) predisposing characteristic when analysing disparities in health care utilization [6]. Migrant populations may have different health care needs, preferences and expectations or face barriers to their use of health services. Previous studies and reviews about inequalities in health care utilization among migrants in Germany or Europe were restricted to particular somatic or mental health outcomes, health care sectors, specific migrant populations, were not systematic or did not include native controls to analyse disparities [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. The aim of this review is to assess inequalities in health care utilization among migrants and natives in Germany. Three research questions are of main interest: (1) Are there inequalities in health care utilization between people with and without migrant background in Germany? (2) Are there differences regarding health care sector or indicator of health care utilization? (3) Are there differences in terms of particular migrant populations and type of migrant background?

Methods

A systematic review was conducted based on the PRISMA guidelines [16]. The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42014015162). The PubMed database was searched including all publications until 1st of June 2017 (for more information about the search strategy see Additional file 1). Furthermore, the search was completed by scanning the references of identified publications and an additional hand search. Inclusion criteria were as follows: eligible articles have to be published or in-press in a peer-reviewed journal and written in English or German language. The studies have to report quantitative and original data of a population residing in Germany, reviews or commentaries were excluded. The indicators of health care utilization have to assess individual behaviour like consultation or participation rates (i.e. studies using biomarker, health outcomes or disease stage at presentation as surrogate for utilization were excluded). Inequality between migrants and natives should be analysed by originating native controls from the same sample. Studies that compare results with normative data or other surveys to analyse inequalities were not included. Moreover, studies that only adjust for the migrant background as a confounder without explicitly reporting associations with health care utilization were excluded. Titles and abstracts of studies were screened by the two authors for eligibility. After the exclusion of studies that did not provide quantitative data on the relation between migrant status and health care utilization, full texts were retrieved. Disagreements on the exclusion of studies were discussed by the two reviewers until a consensus was found. In some cases, the investigators were contacted for further questions. Information extracted from the selected studies includes: first author and publication date, net sample size, area, year of data collection, operationalization of migrant background, indicator(s) of health care utilization, adjustments in the full model (if applicable), statistical measure (i.e., percentage, mean, odds ratio, relative risk etc.) and findings. In terms of adjustment, gender, age and socioeconomic status (SES) were considered as covariates in most studies. Results were specified when 1st and 2nd generation migrants or one- or two-sided migrant background were distinguished in the studies. Moreover, the qualitative assessment of the trend of inequality in the different health care sectors were summarised in a table. A meta-analysis including pooled estimates as well as an assessment of study quality and risk of bias was not conducted due to the number of studies and their heterogeneity concerning health care sectors (e.g. diverse outpatient care, inpatient care, rehabilitation and prevention programs) and methodological approaches (e.g. sample characteristics, outcome measurements, statistical analyses and reported effect estimates).

Results

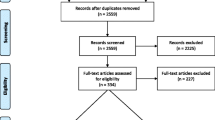

The initial search in PubMed Database generated 822 records. After screening of titles and abstracts 86 publications remain for a full-text review. Thereof, 34 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. Main reasons for exclusion were an ineligible indicator of health care utilization or the absence of native controls within the sample. Additionally, 11 records were found by screening the reference lists of all extracted articles and by hand search resulting in 63 studies finally included in the review. Detailed information is provided in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1.

The publications were categorised according to the following groups which are summarised in the Additional files 2, 3 and 4 including a more detailed presentation of measurements, statistical methods and findings:

-

utilization of outpatient care (subdivided into unspecific physician consultation, general practitioner (GP)/paediatrician), specialist care, inpatient care, emergency care and rehabilitation (Additional file 2),

-

utilization of therapists, counselling services and medication use (incl. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)) (Additional file 3), and

-

utilization of disease prevention provided by a physician (i.e. early cancer detection, early detection program for children, vaccination, general health check-up, oral health check-up) (Additional file 4). Utilization of health promotion programs (e.g. behavioural prevention programs) was not included into the review.

Outpatient care (physicians), inpatient care, emergency care and rehabilitation

Five publications examined associations regarding unspecific outpatient care (i.e. no distinction between GP/paediatrician and specialist) [17,18,19,20,21]. Overall, a slightly higher utilization among people with migrant background (PMB) was reported. The utilization of GPs and paediatricians was assessed by five studies showing small differences between PMB and the non-migrant population (NMP) [22,23,24,25,26]. The largest number of studies (n = 14) was found for specialist consultations [22, 23, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The majority of the results showed lower utilization for PMB, especially among 1st generation migrants. For instance, one study showed a lower probability of utilization especially among 1st generation migrants (odds ratio (OR): 0.58; confidence interval (CI): 0.40–0.83) [23]. Inpatient care was assessed by the number of hospitalizations and elective surgeries (mostly caesarean section) [17, 18, 23, 25, 26, 29, 30, 37,38,39]. The 10 studies revealed an inconsistent pattern in terms of ethnical disparities. The small number of studies (n = 3) that examined emergency care utilization do not enable a definitive conclusion. One current publication showed higher utilization [40] among PMB while two others found no differences [26, 41]. Also, the four studies regarding the utilization of rehabilitation (out- and inpatient) provide insufficient evidence [26, 42,43,44], albeit the trend suggests a lower participation among PMB. A table with all details of the selected studies is provided in Additonal file 2.

Therapists, counselling services and medication

The publications that investigated inequalities in using therapists and counselling services (n = 8) mostly reported lower utilization among PMB. This holds true for physical (adult 1st generation migrants, children and adolescents) [45, 46] and occupational therapy (children and adolescents) [47], psychosocial care/counselling [26, 28, 48], but not for the two studies analysing utilization of psychotherapists and psycho-oncologists [22, 49]. In terms of physical therapy, a recent multi-level analysis found a lower probability of utilization among 1st generation migrants (OR: 0.67; CI: 0.51–0.89) [45]. Medication use (especially self-medication/over-the-counter drugs) [50,51,52] and utilization of CAM [24, 26, 53,54,55,56] (13 studies) was more prevalent among NMP (adults as well as children and adolescents). There is no clear pattern in terms of prescribed drugs and off-label medicine (see Additional file 3 for more details) [51, 57,58,59].

Disease prevention

Compared to the other health care sectors, there are more studies on migrant-specific utilization of disease prevention programs (in sum n = 34). In case of early cancer detection, five out of seven studies indicated lower participation for PMB [17, 26, 60,61,62,63,64]. Particularly, this holds true for migrants of the 1st generation or with a two-sided migrant background. Similarly, the participation in preventive health care programs for children aged zero to 5 years (named “u-examinations” in the German health care system) is consistently less prevalent among PMB [25, 65,66,67,68]. A different pattern was shown in terms of vaccination uptake. Subject to the type of vaccination, inequalities substantially vary, so a clear trend cannot be identified [41, 61, 66, 67, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77]. Only two studies examined ethnic inequalities in the utilization of the general health check-up that is offered to every person aged ≥35 years [26, 61]. PMB participated less often. Finally, consistent inequalities were shown when participation in oral health check-ups was investigated, with PMB showing lower rates in all age groups (see Additional file 4 for more details) [24, 26, 27, 58, 61, 78, 79]. For example, a recent publication among adults showed a significantly lower probability of utilization of oral health check-ups even in the fully adjusted model (OR: 0.71; CI: 0.65–0.77) [78].

A summary of the findings including number of studies, trend of inequality and description of trend for all health care sectors is provided in Table 1.

Discussion

There are inequalities in health care utilization between migrants and natives in Germany. These disparities vary in terms of health care sector, indicator of health care utilization and migrant population. A lower utilization among PMB was particularly shown for specialist care, medication use, therapist consultations and counselling as well as disease prevention (especially early cancer detection, prevention programs for children and oral health check-ups). No disparities or inconsistent patterns were shown for GP/paediatrician visits, inpatient care and vaccinations. A low number of studies regarding emergency and general health check-up does not allow a clear statement. Usage of rehabilitation tends to be more prevalent among NMP. Furthermore, migrants of the 1st generation, people with two-sided migrant background, children and adolescents as well as women were identified as migrant groups with a particularly low utilization. Studies from other European countries are in line with some presented results. Two systematic reviews showed higher utilization of emergency departments by migrants [10, 11] while one indicated inconsistent results [12]. Furthermore, specialist visits and screening uptake were reduced among PMB in different countries [11, 12]. This also holds true for the utilization of mental health care [13].

Moreover, it is an important topic if the SES (income, education, occupational status) contributes to potential inequalities between migrants and non-migrants [80, 81]. Notably, the pattern of migrant-specific inequalities in health care utilization is quite similar to disparities in utilization regarding SES [82]. Some of the extracted studies aimed at analysing the contribution of SES concerning ethnic disparities in health care utilization [42, 62, 64]. Even after stepwise introduction of SES variables into the model, no or only a low reduction of the association between migrant background and health care utilization was shown for different health care sectors. A number of studies introduce various covariates (including SES variables) at once into the analysis, and both the estimates of migrant background and SES remain significant (data not shown in detail) [e.g. 40, 45, 51, 53, 78]. In other cases, the association with migrant background is significant while the association with SES is not [19, 72, 20]. These results suggest that in many cases, migrant background/ethnicity is a determinant of health care use, independent from SES, and associations between migrant status and health care utilization cannot substantially be explained by SES.

Reasons for differences in health care utilization

Differences in health care utilization between migrants and non-migrants can imply acceptable or unacceptable inequalities [83]. The former include differences in expectations and preferences (e.g. individual/cultural preferences or health beliefs), the latter mean differences in information (e.g. about service availability), language/communication or (formal) access barriers (e.g. charges, waiting times, travel distances or lost wages). For the majority of the extracted studies, it is not possible to figure out the reasons for non-utilization of health care. In a German survey, language barriers, lack of information about the health care system and the assumption that cultural peculiarities would not be understood by the expert staff were indicated as the main reasons for a non-utilization (any health care sector) [84]. Another study including patients in a paediatric setting and health care providers found out that a major difficulty was the lack of mutual understanding, often associated with language barriers and difficulties in managing cultural diversity [85]. In mental health care, translation problems and misunderstandings based on divergent explanations in terms of the causes, course, and adequate treatment of different disorders were found to play an important role [86]. Furthermore, lower health literacy (i.e. knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information) for migrants living in Germany than for German natives were shown for different age groups [87]. A lower utilization of, for instance, over-the-counter drugs could be due not only to lower health literacy but also to limited financial resources. Another barrier comprises factors of discrimination. US-American research examined that a higher prevalence of discrimination among ethnic minorities may contribute to their underutilization of health care services [88]. Finally, differences in health care needs could also be a reason for disparities in health care utilization [6, 83]. There is still a lack of evidence and unclear patterns about health care needs of migrants. Often, they are initially healthier compared with NMP (healthy migrant effect) while some data suggest that they tend to be more vulnerable to certain diseases [2, 89].

Strengths and limitations

Generally, most of the studies were cross-sectional and had a descriptive and explorative approach. So, no causal conclusion can be drawn and most of the inequalities could not be explained by statistical data. Studies differ in the assessment and definition of migration status/background (e.g. country of birth, nationality, language spoken at home) including information about important subgroups (e.g. 1st/2nd generation, one- or two-sided background) and in recruitment strategies (register-based, community-orientated) [90, 91]. Therefore, comparability of the data is somewhat limited. Furthermore, some articles did not focus on migrants although results regarding migrant background as covariate was shown in the tables. Thus, the identification of eligible studies is hampered to a certain degree. The reference screening of the identified publications and the additional hand search was aimed to minimize that potential limitation. As mentioned in the Methods section, a meta-analysis including a risk of bias assessment and a pooled estimate could not be conducted due to the methodological heterogeneity of the selected studies. The qualitative synthesis of inequality was not based on a specific criterion. Moreover, the aforementioned adjustment of need (e.g. level of ill-health, capacity to benefit from health care or the expenditure a person ought to have) was not (or insufficiently) realized in the majority of the studies [83]. Often, the subjective health status was used as a proxy for need and this measure is amongst others known to be biased by ethnicity [92]. Finally, due to a comparatively small number of studies, evidence is not sufficient for conclusions in terms of some health care sectors (emergency care, rehabilitation, general health check-up).

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive systematic review that worked out migrant-specific inequalities in health care utilization for numerous health care sectors and migrant populations in Germany. The detailed and sensitive search strategy was aimed to identify all relevant publications and to provide evidence of ethnic disparities in German health care. However, it is possible that additional studies could not been identified, but it is assumed that additional results would not have altered the overall findings. Nevertheless, a publication bias could have limited the results as studies resulting in weak or no associations at all tend to be published less often.

Implications and interventions

Generally, two different strategies are discussed to address migrant populations. ‘Exclusive’ migrant-specific strategies imply services and interventions specifically addressed at this group [93]. It is argued that differences in e.g. biology, life course, language, culture between migrants and natives require specific health and preventive interventions. Potential stigmata and the heterogeneity of migrant groups are named to be disadvantageous for this strategy. The ‘inclusive’ migrant-sensitive approach aims at adapting the existing routine health and preventive services to the specific requirements. Thus, the social determinants of health which affect all members of a society underlie ethnic disparities, whilst cultural differences would be overestimated [94]. There is strong evidence that social inequalities in health, health care access and utilization are a major topic for health policy in various countries [95, 96]. For the case of Germany, this review shows that patterns of ethnic inequalities in health care utilization are quite similar to inequalities according to SES (i.e. income-related, educational, occupational), but the ethnic disparities could not substantially be explained by the SES of the patients. There are controversial discussions if differences in SES are the essential explanation for migrant-specific disparities in health and health care [80, 81]. Indeed, the assumption that migration is an independent social determinant of health is becoming more and more popular [80, 97]. The complexity of social inequalities among ethnic minority groups cannot be fully captured by simple measures of SES. Specifics among migrants are a non-comparability of SES markers across ethnic groups, the importance of life course inequalities and other risk factors like racism and geographical segregation that may affect health. Finally, a mixture of health care programs that include (migrant-sensitive) and specifically address (migrant-specific) PMB is needed [98].

Beside the discussion of fundamental strategies, the aforementioned different aspects of non- or under-utilization implies different needs for action in practice. The German concept of “intercultural opening” implies reduction of communication barriers by using interpreters, mediating between divergent explanations, avoiding cultural stereotyping and supporting an open-minded, reflective professional approach [86, 99]. Language barriers are often mentioned to be a major problem for migrants when accessing and utilizing health care. Professional face-to-face interpretation, professional interpretation by telephone, informal face-to-face interpretation, bilingual professionals or cultural mediators (health workers) are methods for tackling language barriers [2]. There are attempts to overcome these barriers (e.g. in a German hospital setting), but the current resources seem not to be appropriate and sufficient [100]. A development of quality standards and the provision of financial resources are recommendations for a significant improvement. Moreover, the strengthening of migrants’ health literacy and knowledge of available care programs by native speaking counselling services, and developing culturally sensitive patient information material aim at improving health care access and utilization of PMB in Germany [101, 102]. The different ways migrants perceive health problems or face administrative requirements has to be of interest, too [2]. For the utilization of prevention or emergency care, tailored education measures on the general functioning of the German health systems should be provided for an improved patient empowerment [40, 98]. For instance, this could be included in integration classes that are offered to people migrating to Germany. Nevertheless, attention should be paid on established formal access barriers for socially deprived people like waiting times, co-payments, travel distances or lost wages [103]. A particular topic for research and intervention programs are the special needs and restricted entitlements for the growing number of refugees, asylum-seekers and undocumented migrants in the recent years [4, 104]. Studies specifically addressing these populations were included into the initial search, but were subsequently excluded due to unmet inclusion criteria [105, 106]. Their insecure residence permit status implies some more formal and informal barriers to access and utilize health care [4]. Experiences of war, devastation and escape leads to particular needs in the fields of psychosocial and mental health, chronic diseases and the provision of care to children [104, 107]. Despite the increased number of publications, a lack of valid data avoids evidence-based decisions.

Conclusions

This comprehensive overview covers numerous health care sectors and migrant populations in association with inequalities of health care utilization in Germany. Overall, people with migrant background indicate a lower utilization of health care, but inequalities vary with health care sector and subpopulation of migrants. The SES cannot substantially explain migrant-specific inequalities. Hence, the enlisted aspects and complexity of migration, health care and their interaction need further efforts in research and practice. With respect to different areas of health care and vulnerable groups, various migrant-specific and migrant-sensitive interventions are required. The current available data provides some references for action.

References

Brzoska P, Ellert U, Kimil A, Razum O, Sass A-C, Salman R, et al. Reviewing the topic of migration and health as a new national health target for Germany. Int J Public Health. 2015;60:13–20.

Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Ingleby D, Mackenbach JP, McKee M. Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet. 2013;381:1235–45.

Federal Statistical Office (Destatis). Statistisches Jahrbuch. 2017. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/StatistischesJahrbuch/StatistischesJahrbuch2017.html. Accessed 24 Oct 2018.

Razum O, Bozorgmehr K. Restricted entitlements and access to health care for refugees and immigrants: the example of Germany. Glob Soc Policy. 2016;16:321–4.

Razum O, Karrasch L, Spallek J. Migration: A neglected dimension of inequalities in health? Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016;59:259–65.

Andersen RM, Davidson PL, Baumeister SE. Improving access to care. In: Kominski GE, editor. Changing the U.S. health care system: key issues in health services, policy, and management. San Francisco: Wiley & Sons; 2014. p. 33–69.

Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. Psycho-Soc Med. 2012;9:Doc11.

Brzoska P, Erdsiek F, Waury D. Enabling and predisposing factors for the utilization of preventive dental health care in migrants and non-migrants in Germany. Front Public Health. 2017;5:201.

Bozorgmehr K, Mohsenpour A, Saure D, Stock C, Loerbroks A, Joos S, et al. Systematic review and evidence mapping of empirical studies on health status and medical care among refugees and asylum seekers in Germany (1990-2014). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016;59:599–620.

Credé SH, Such E, Mason S. International migrants’ use of emergency departments in Europe compared with non-migrants’ use: a systematic review. Eur J Pub Health. 2018;28:61–73.

Graetz V, Rechel B, Groot W, Norredam M, Pavlova M. Utilization of health care services by migrants in Europe—a systematic literature review. Br Med Bull. 2017;121:5–18.

Norredam M, Nielsen SS, Krasnik A. Migrants’ utilization of somatic healthcare services in Europe--a systematic review. Eur J Pub Health. 2010;20:555–63.

Lindert J, Schouler-Ocak M, Heinz A, Priebe S. Mental health, health care utilisation of migrants in Europe. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:14–20.

Kowalski C, Loss J, Kölsch F, Janssen C. Utilization of prevention services by gender, age, socioeconomic status, and migration status in Germany: an overview and a systematic review. In: Janssen C, Swart E, von Lengerke T, editors. Health care utilization in Germany. New York: Springer; 2014. p. 293–320.

Schouler-Ocak M. Mental health care for immigrants in Germany. Nervenarzt. 2015;86:1320–5.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, et al.. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6.

Aparicio ML, Döring A, Mielck A, Holle R, KORA Study-Group. Differences between eastern European immigrants of German origin and the rest of the German population in health status, health care use and health behaviour: a comparative study using data from the KORA-Survey 2000. Soz Praventivmed. 2005;50:107–18.

Bächle C, Haastert B, Holl RW, Beyer P, Grabert M, Giani G, et al. Inpatient and outpatient health care utilization of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes before and after introduction of DRGs. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118:644–8.

Fassmer AM, Ramos AL, Boiselle C, Dreger S, Helmer S, Zeeb H. [Tobacco Use and Utilization of Medical Services in Adolescence: An Analysis of the KiGGS Data]. Gesundheitswesen 2016. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-116590.

Hirschfeld G, Wager J, Zernikow B. Physician consultation in young children with recurrent pain-a population-based study. PeerJ. 2015;3:e916.

Sundmacher L, Kopetsch T. Waiting times in the ambulatory sector - the case of chronically ill patients. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:77.

Bermejo I, Frank F, Maier I, Hölzel LP. Health care utilisation of migrants with mental disorders compared with Germans. Psychiatr Prax. 2012;39:64–70.

Glaesmer H, Wittig U, Braehler E, Martin A, Mewes R, Rief W. Health care utilization among first and second generation immigrants and native-born Germans: a population-based study in Germany. Int J Public Health. 2011;56:541–8.

Huber J, Lampert T, Mielck A. Inequalities in health risks, morbidity and health care of children by health insurance of their parents (statutory vs. private health insurance): results of the German KiGGS study. Gesundheitswesen. 2012;74:627–38.

Kamtsiuris P, Bergmann E, Rattay P, Schlaud M. Use of medical services. Results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50:836–50.

Zeeb H, Baune BT, Vollmer W, Cremer D, Krämer A. Health situation of and health service provided for adult migrants--a survey conducted during school admittance examinations. Gesundheitswesen. 2004;66:76–84.

Aarabi G, Reissmann DR, Seedorf U, Becher H, Heydecke G, Kofahl C. Oral health and access to dental care - a comparison of elderly migrants and non-migrants in Germany. Ethn Health. 2017:1–15.

Brenne S, David M, Borde T, Breckenkamp J, Razum O. Are women with and without migration background reached equally well by health services? The example of antenatal care in Berlin. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:569–76.

David M, Borde T, Brenne S, Ramsauer B, Henrich W, Breckenkamp J, et al. Comparison of perinatal data of immigrant women of Turkish origin and German women - results of a prospective study in Berlin. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2014;74:441–8.

David M, Schwartau I, Anand Pant H, Borde T. Emergency outpatient services in the city of Berlin: factors for appropriate use and predictors for hospital admission. Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13:352–7.

Gruber S, Kiesel M. Inequality in health care utilization in Germany? Theoretical and empirical evidence for specialist consultation. J Public Health. 2010;18:351–65.

Kavuk I, Weimar C, Kim BT, Gueneyli G, Araz M, Klieser E, et al. One-year prevalence and socio-cultural aspects of chronic headache in Turkish immigrants and German natives. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:1177–81.

Koller D, Lack N, Mielck A. Social differences in the utilisation of prenatal screening, smoking during pregnancy and birth weight--empirical analysis of data from the perinatal study in Bavaria (Germany). Gesundheitswesen. 2009;71:10–8.

Reime B, Lindwedel U, Ertl KM, Jacob C, Schücking B, Wenzlaff P. Does underutilization of prenatal care explain the excess risk for stillbirth among women with migration background in Germany? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:1276–83.

Simoes E, Kunz S, Schmahl F. Utilisation gradients in prenatal care prompt further development of the prevention concept. Gesundheitswesen. 2009;71:385–90.

Spallek J, Lehnhardt J, Reeske A, Razum O, David M. Perinatal outcomes of immigrant women of Turkish, Middle Eastern and North African origin in Berlin, Germany: a comparison of two time periods. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:505–12.

David M, Borde T, Brenne S, Henrich W, Breckenkamp J, Razum O. Caesarean section frequency among immigrants, second- and third-generation women, and non-immigrants: prospective study in Berlin/Germany. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127489.

Geyer S, Peter R, Siegrist J. Socioeconomic differences in children’s and adolescents’ hospital admissions in Germany: a report based on health insurance data on selected diagnostic categories. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:109–14.

Icks A, Rosenbauer J, Strassburger K, Grabert M, Giani G, Holl RW. Persistent social disparities in the risk of hospital admission of paediatric diabetic patients in Germany-prospective data from 1277 diabetic children and adolescents. Diabet Med. 2007;24:440–2.

Kietzmann D, Knuth D, Schmidt S. (Non-)utilization of pre-hospital emergency care by migrants and non-migrants in Germany. Int J Public Health. 2017;62:95–102.

Wenner J, Razum O, Schenk L, Ellert U, Bozorgmehr K. The health of children and adolescents from families with insecure residence status compared to children with permanent residence permits: analysis of KiGGS data 2003–2006. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016;59:627–35.

Brzoska P, Voigtländer S, Spallek J, Razum O. Utilization and effectiveness of medical rehabilitation in foreign nationals residing in Germany. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:651–60.

Ritter S, Dannenmaier J, Jankowiak S, Kaluscha R, Krischak G. [Total hip and knee arthroplasty - utilization of postoperative rehabilitation]. Rehabil. 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-102135.

Zollmann P, Pimmer V, Rose AD, Erbstosser S. Comparison of psychosomatic rehabilitation for German and foreign patients. Rehabilitation. 2016;55:357–68.

Rommel A, Kroll LE. Individual and regional determinants for physical therapy utilization in Germany: multilevel analysis of national survey data. Phys Ther. 2017;97:512–23.

Weber A, Karch D, Thyen U, Rommel A, Schlack R, Hölling H, et al. Utilization of physiotherapy services by children and adolescents - results of the KiGGS- baseline survey. Gesundheitswesen. 2016;79:164–73.

Weber A, Karch D, Thyen U, Rommel A, Schlack R, Hölling H, et al. Utilization of occupational therapy in children - results from the KiGGS basis survey. Klin Padiatr. 2016;228:77–83.

Häfner S, Schmidt-Lachenmann B. Psychic symptoms and mental health service utilization - an epidemiologic study in the city of Stuttgart. Gesundheitswesen. 2008;70:81–7.

Zeissig SR, Singer S, Koch L, Zeeb H, Merbach M, Bertram H, et al. Utilisation of psychosocial and informational services in immigrant and non-immigrant German cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2015;24:919–25.

Du Y, Knopf H. Self-medication among children and adolescents in Germany: results of the National Health Survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS). Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:599–608.

Eckel N, Sarganas G, Wolf I-K, Knopf H. Pharmacoepidemiology of common colds and upper respiratory tract infections in children and adolescents in Germany. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;15:44.

Knopf H. Medicine use in children and adolescents. Data collection and first results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50:863–70.

Du Y, Knopf H. Paediatric homoeopathy in Germany: results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:370–9.

Du Y, Wolf I-K, Zhuang W, Bodemann S, Knöss W, Knopf H. Use of herbal medicinal products among children and adolescents in Germany. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:218.

Kalder M, Knoblauch K, Hrgovic I, Münstedt K. Use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy and delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:475–82.

Mani J, Juengel E, Arslan I, Bartsch G, Filmann N, Ackermann H, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine before and after organ removal due to urologic cancer. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1407–12.

Knopf H, Hölling H, Huss M, Schlack R. Prevalence, determinants and spectrum of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication of children and adolescents in Germany: results of the German health interview and examination survey (KiGGS). BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000477.

Knopf H, Rieck A, Schenk L. Oral hygiene. KIGGS data on caries preventative behaviour. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2008;51:1314–20.

Knopf H, Wolf I-K, Sarganas G, Zhuang W, Rascher W, Neubert A. Off-label medicine use in children and adolescents: results of a population-based study in Germany. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:631.

Berens E-M, Stahl L, Yilmaz-Aslan Y, Sauzet O, Spallek J, Razum O. Participation in breast cancer screening among women of Turkish origin in Germany - a register-based study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:24.

Brand T, Kleer D, Samkange-Zeeb F, Zeeb H. Prevention among migrants: participation, migrant sensitive strategies and programme characteristics. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:584–92.

Brzoska P, Abdul-Rida C. Participation in cancer screening among female migrants and non-migrants in Germany: A cross-sectional study on the role of demographic and socioeconomic factors. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4242.

Lemke D, Berkemeyer S, Mattauch V, Heidinger O, Pebesma E, Hense H-W. Small-area spatio-temporal analyses of participation rates in the mammography screening program in the city of Dortmund (NW Germany). BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1190.

Rommel A, Saß AC, Born S, Ellert U. Health status of people with a migrant background and impact of socio-economic factors: first results of the German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:543–52.

Becker S, Kurz K. Social inequality in early childhood health – participation in the preventive health care program for children. Schmollers Jahrb. 2011;131:381–9.

Koller D, Mielck A. Regional and social differences concerning overweight, participation in health check-ups and vaccination. Analysis of data from a whole birth cohort of 6-year old children in a prosperous German city. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:43.

Rosenkötter N, van Dongen MCJM, Hellmeier W, Simon K, Dagnelie PC. The influence of migratory background and parental education on health care utilisation of children. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:1533–40.

Stich HL, Mikolajczyk RT, Krämer A. Determinants of participation in paediatric preventive health care examinations (U1–U8). A public health analysis of health services in childhood. Präv Gesundheitsf. 2009;4:265–71.

Bödeker B, Remschmidt C, Müters S, Wichmann O. Influenza, tetanus, and pertussis vaccination coverage among adults in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:174–81.

Böhmer MM, Walter D, Krause G, Müters S, Gösswald A, Wichmann O. Determinants of tetanus and seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in adults living in Germany. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7:1317–25.

Mikolajczyk RT, Akmatov MK, Stich H, Krämer A, Kretzschmar M. Association between acculturation and childhood vaccination coverage in migrant populations: a population based study from a rural region in Bavaria, Germany. Int J Public Health. 2008;53:180–7.

Poethko-Müller C, Ellert U, Kuhnert R, Neuhauser H, Schlaud M, Schenk L. Vaccination coverage against measles in German-born and foreign-born children and identification of unvaccinated subgroups in Germany. Vaccine. 2009;27:2563–9.

Poethko-Müller C, Kuhnert R, Schlaud M. Vaccination coverage and predictors for vaccination level. Results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS). Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50:851–62.

Remschmidt C, Walter D, Schmich P, Wetzstein M, Deleré Y, Wichmann O. Knowledge, attitude, and uptake related to human papillomavirus vaccination among young women in Germany recruited via a social media site. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2014;10:2527–35.

Remschmidt C, Fesenfeld M, Kaufmann AM, Deleré Y. Sexual behavior and factors associated with young age at first intercourse and HPV vaccine uptake among young women in Germany: implications for HPV vaccination policies. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1248.

Samkange-Zeeb F, Spallek L, Klug SJ, Zeeb H. HPV infection awareness and self-reported HPV vaccination coverage in female adolescent students in two German cities. J Community Health. 2012;37:1151–6.

Stumm C, Hahn D, Heberlein I, Doherr F, Hofmann W. Knowledge of human papillomavirus infection and the possibilities for prevention among 13- to 21-year-old students from Fulda, Hessen. Gesundheitswesen. 2017;79:399–406.

Erdsiek F, Waury D, Brzoska P. Oral health behaviour in migrant and non-migrant adults in Germany: the utilization of regular dental check-ups. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17:84.

Kühnisch J, Heinrich-Weltzien R, Senkel H. Oral health and use of dental care by 8-year-old immigrants and German students of the Ennepe-Ruhr district. Gesundheitswesen. 1998;60:500–4.

Nazroo JY, Williams DR. The social determination of ethnical/racial inequalities in health. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson GR, editors. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 238–66.

WHO. How health systems can address health inequities linked to migration and ethnicity. 2017. http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/how-health-systems-can-address-health-inequities-linked-to-migration-and-ethnicity. Accessed 24 Oct 2018.

Klein J, Hofreuter-Gätgens K, von dem Knesebeck O. Socioeconomic status and the utilization of health services in Germany: a systematic review. In: Janssen C, Swart E, von Lengerke T, editors. Health care utilization in Germany. New York: Springer; 2014. p. 117–43.

Allin S, Masseria C, Sorenson C, Papanicolas I, Mossialos E. Measuring inequalities in access to health care: a review of the indices. European Commission. 2007. http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?langId=en&docId=3952&. Accessed 24 Oct 2018.

Bermejo I, Hölzel LP, Kriston L, Härter M. Barriers in the attendance of health care interventions by immigrants. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2012;55:944–53.

Ciupitu CC, Babitsch B. Why is it not working? Identifying barriers to the therapy of paediatric obesity in an intercultural setting. J Child Health Care. 2011;15:140–50.

Penka S, Schouler-Ocak M, Heinz A, Kluge U. Cross-cultural aspects of interaction and communication in mental health care. Barriers and recommendations for action. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2012;55:1168–75.

Quenzel G, Vogt D, Schaeffer D. Differences in health literacy of adolescents with lower educational attainment, older people and migrants. Gesundheitswesen. 2016;78:708–10.

Burgess DJ, Ding Y, Hargreaves M, van Ryn M, Phelan S. The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:894–911.

Kohls M. Mortality risks of migrants: analysis of the healthy-migrant-effect after the 2011 German census. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:519–26.

Reiss K, Makarova N, Spallek J, Zeeb H, Razum O. Identification and sampling of people with migration background for epidemiological studies in Germany. Gesundheitswesen. 2013;75:e49–58.

Reiss K, Dragano N, Ellert U, Fricke J, Greiser KH, Keil T, et al. Comparing sampling strategies to recruit migrants for an epidemiological study. Results from a German feasibility study. Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24:721–6.

Lindeboom M, Van Doorslaer E. Cut-point shift and index shift in self-reported health. J Health Econ. 2004;23:1083–99.

Razum O, Spallek J. Addressing health-related interventions to immigrants: migrant-specific or diversity-sensitive? Int J Public Health. 2014;59:893–5.

Razum O, Stronks K. The health of migrants and ethnic minorities in Europe: where do we go from here? Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24:701–2.

Fjær EL, Stornes P, Borisova LV, McNamara CL, Eikemo TA. Subjective perceptions of unmet need for health care in Europe among social groups: findings from the European social survey (2014) special module on the social determinants of health. Eur J Pub Health. 2017;27:82–9.

Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, Goldblatt P, Consortium for the European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380:1011–29.

Castañeda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, Young M-ED, Beyeler N, Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:375–92.

Spallek J, Zeeb H, Razum O. Prevention among immigrants: the example of Germany. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:92.

Penka S, Kluge U, Vardar A, Borde T, Ingleby D. The concept of “intercultural opening”: the development of an assessment tool for the appraisal of its current implementation in the mental health care system. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(Suppl 2):63–9.

Langer T, Zapf T, Wirth S, et al. How are pediatric hospitals in North-Rhine Westfalia prepared to overcome language barriers? A pilot study exploring the structural quality of inpatient care. Gesundheitswesen. 2017;79:535–41.

Hölzel LP, Ries Z, Zill JM, Kriston L, Dirmaier J, Härter M, et al. Development and testing of culturally sensitive patient information material for Turkish, polish, Russian and Italian migrants with depression or chronic low back pain (KULTINFO): study protocol for a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:265.

Horn A, Vogt D, Messer M, Schaeffer D. Strengthening health literacy of people with migration background: results of a qualitative evaluation. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:577–83.

Klein J, von dem Knesebeck O. Social disparities in outpatient and inpatient care: an overview of current findings in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016;59:238–44.

Frank L, Yesil-Jürgens R, Razum O, et al. Health and healthcare provision to asylum seekers and refugees in Germany. Journal of Health Monitoring. 2017;2:22–42.

Bozorgmehr K, Schneider C, Joos S. Equity in access to health care among asylum seekers in Germany: evidence from an exploratory population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:502.

Schneider C, Joos S, Bozorgmehr K. Disparities in health and access to healthcare between asylum seekers and residents in Germany: a population-based cross-sectional feasibility study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008784.

Bajbouj M, Alabdullah J, Ahmad S, Schidem S, Zellmann H, Schneider F, Heuser I. Psychosocial care of refugees in Germany: insights from the emergency relief and development aid. Nervenarzt. 2018;89:1–7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study did not receive any funding.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JK and OvdK designed the study, JK developed the searches, JK and OvdK screened and analysed the literature, JK drafted the manuscript and interpreted the findings, OvdK contributed to writing and provided feedback on drafts. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. (PDF 168 kb)

Additional file 2:

Overview of the characteristics of included studies (utilization of outpatient care (physicians), inpatient care, emergency care and rehabilitation). (DOCX 31 kb)

Additional file 3:

Overview of the characteristics of included studies (utilization of therapists and counselling services, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and medication use). (DOCX 20 kb)

Additional file 4:

Overview of the characteristics of included studies (utilization of disease prevention). (DOCX 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Klein, J., von dem Knesebeck, O. Inequalities in health care utilization among migrants and non-migrants in Germany: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health 17, 160 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0876-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0876-z