Abstract

Background

Although a number of studies on infectious disease trends in China exist, these studies have not distinguished the age, period, and cohort effects simultaneously. Here, we analyze infectious disease mortality trends among urban and rural residents in China and distinguish the age, period, and cohort effects simultaneously.

Methods

Infectious disease mortality rates (1990–2010) of urban and rural residents (5–84 years old) were obtained from the China Health Statistical Yearbook and analyzed with an age-period-cohort (APC) model based on Intrinsic Estimator (IE).

Results

Infectious disease mortality is relatively high at age group 5–9, reaches a minimum in adolescence (age group 10–19), then rises with age, with the growth rate gradually slowing down from approximately age 75. From 1990 to 2010, except for a slight rise among urban residents from 2000 to 2005, the mortality of Chinese residents experienced a substantial decline, though at a slower pace from 2005 to 2010. In contrast to the urban residents, rural residents experienced a rapid decline in mortality during 2000 to 2005. The mortality gap between urban and rural residents substantially narrowed during this period. Overall, later birth cohorts experienced lower infectious disease mortality risk. From the 1906–1910 to the 1941–1945 birth cohorts, the decrease of mortality among urban residents was significantly faster than that of subsequent birth cohorts and rural counterparts.

Conclusions

With the rapid aging of the Chinese population, the prevention and control of infectious disease in elderly people will present greater challenges. From 1990 to 2010, the infectious disease mortality of Chinese residents and the urban-rural disparity have experienced substantial declines. However, the re-emergence of previously prevalent diseases and the emergence of new infectious diseases created new challenges. It is necessary to further strengthen screening, immunization, and treatment for the elderly and for older cohorts at high risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, with the improvement of living standards and the development of medical and health services, the health of Chinese residents has been greatly improved. Disease patterns have also undergone tremendous change in that chronic rather than infectious diseases have become the leading cause of death [1–3]. Most infectious diseases have been eliminated or controlled at a low endemic level since the 1990s. However, upon entering the 21st century, China is facing a complex scenario involving the re-emergence of previously prevalent diseases and the emergence of new infectious diseases [4, 5]. Entities that continue to pose serious threats to lives and health include HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases (e.g., syphilis, gonorrhea), viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, and zoonoses (e.g., rabies, SARS, HPAI, and H1N1). Recent infectious disease outbreaks such as SARS, HPAI, and H1N1 remind us that any slackness in prevention and control will probably trigger disease re-emergence [5]. Infectious diseases not only harm lives and health, but also lead to economic losses and social instability. Considering the increasingly close contacts between China and the rest of the world, infectious diseases are no longer just local issues: if not quickly detected and contained, they may transform into national and even global pandemics [4]. Therefore, the scientific measurement of trends in China’s infectious diseases is critical.

When researching the development trend of infectious diseases in China, special attention should be paid to the unbalanced development between urban and rural areas. In addition to basic living standards, there is also a considerable gap in health services between them. Therefore, the capacity for the prevention and control of infectious diseases in these settings is different. In China, most medical resources are concentrated in urban areas, including the best medical institutions, facilities, and personnel [6]. In 2012, the health expenditure per capita was 2,969 yuan for urban residents and only 1,056 yuan for rural residents; the former is 2.8 times that of the latter [7]. Urban and rural residents are also subject to different health insurance schemes and a widening income gap. Thus, with the rapid increase of health care costs, their medical burdens are different [1, 8–11]. The fourth National Health Services Survey in 2008 showed that the proportions of urban and rural residents who were ill but did not take any therapeutic measures within the last two weeks were 6.4 % and 12.4 % respectively and the proportions of residents untreated for economic reasons were 23.2 % and 30.6 %. The values of both indicators were significantly lower among urban residents than rural residents [12].

A number of studies on infectious disease trends in China already exist. These studies investigated either a variety of infectious diseases [4, 5] or focused on a specific entity. Studied disease entities include HIV/AIDS [13–17], sexually transmitted diseases [18–20], viral hepatitis [21–23], tuberculosis [24–26], rabies [27, 28], and others [29–31]. They focused on comparing infectious disease trends across years, and more detailed studies cared age-specific trends. One disadvantage of these studies is that they did not distinguish the age, period, and cohort effectsFootnote 1 simultaneously. These should be distinguished not only because of their differences, but also because failing to do so leads to bias and makes reliable conclusions difficult to get [32, 33], thereby affecting trend attribution. Although some studies have started using APC models to analyze infectious disease trends outside mainland China [34–37], the model estimation method used in these studies has some disadvantages (see methods section). To overcome shortcomings of former studies, we used the IE [38] to estimate the model. Compared with other methods, this estimation method can not only solve the problem of model identification, but also provide unbiased and relatively efficient estimation results [39, 40].

Here, we aim to analyze infectious disease mortality trends (1990–2010) of urban and rural Chinese residents (5–84 years old) using the APC model and to distinguish the age, period, and cohort effects simultaneously. First, through a descriptive analysis of age-specific mortality rates, we will obtain a visual impression of age, period, and birth cohort effects as well as demonstrate the need to distinguish these three effects. We then use the IE method to estimate the coefficients of the age, period, and cohort variation in infectious disease mortality.

Methods

The age-specific infectious disease mortality rates used in this study were obtained from the China Health Statistical Yearbook. Mortality rates were collected for 5-year age groups. The APC models requires a uniform age group interval [41], and therefore the 0, 1–4, and above 85 age groups were not included in the analysis. Since the mortality rates were organized in 5-year age groups, data with a 5-year interval were used according to the requirement of the APC model at the collective level. In view of data availability and the APC model requirements, this paper analyzes the infectious disease mortality of Chinese urban and rural residents from 1990 to 2010. As data of year 2000 were not available, we used the mean values of the 1999 and 2001 mortality to represent them.

Age-specific infectious disease mortality rates are summarized in the a × p table with a age groups and p time periods. The diagonal elements of the matrix denote c (c = a + p-1) cohorts. The oldest birth cohort observations appear in the oldest age group and earliest years, and the youngest appear in the youngest age group and latest years. The data used in this study comprise 16 5-year age groups ranging from 5–9 to 80–84 and 5 period points with a 5-year interval from 1990 to 2010. These yielded 20 successive 5-year birth cohorts of which the oldest cohort was born in 1906–1910 (80–84 years old in 1990) and the youngest cohort was born in 2001–2005 (5–9 years old in 2010).

Methods

When analyzing infectious disease mortality, we constructed an APC model using the Poisson log-linear model [42]:

In this model, rijk denotes the expected death rate of the i-th age group in the j-th year (k-th birth cohort); dijk denotes the expected number of deaths and is assumed to be distributed as a Poisson variate; nijkdenotes the number of people exposed at risk; μ denotes the intercept or adjusted mean; αi denotes the effect of the i-th age group (i = 1,……,a); βj denotes the effect of the j-th year (j = 1,……,p); and γk denotes the effect of k-th birth cohort (k = 1,……,c), where c = a + p-1.

For a long time, the use of Eq. (1) to construct the APC model was hindered by the so-called “model identification problem”: Because there is a linear relationship between age, period, and birth cohort (Birth Cohort = Period - Age), a definite solution of the model cannot be obtained using traditional estimation methods such as the ordinary least squares method. Although researchers have made various attempts to resolve the problem, such as using a reduced model containing two of the factors or constraining the model parameters [43], no satisfactory solution was identified totally. The use of a reduced model ignores the third effect, while constraining the parameters depends heavily on certain assumptions that are difficult to verify [39, 40]. Here, we use IE [38] to construct the model, which not only solves the problem of model identification but also provides unbiased and relatively efficient estimation results [39, 40].

Results and discussion

Descriptive analysis

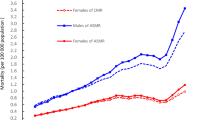

To obtain a visual impression of the age, period, and birth cohort effects of infectious disease mortality and demonstrate the need to distinguish these three effects, we analyzed age-specific mortality rates by period (Fig. 1a) and cohort (Fig. 1b). Fig. 1a shows that mortality is relatively high at age 5–9 but reaches a minimum in adolescence (age 10–19) before rising with age. However, the age pattern in Fig. 1b is quite different from that in Fig. 1a, showing that mortality might not increase with age but instead decline for some birth cohorts. From 1990 to 2010, the infectious disease mortality of urban and rural residents continuously declined, except that the mortality of urban residents showed no apparent decline between 2000 and 2005. By contrast, the mortality of rural residents declined rapidly during 2000 to 2005. During 1990 to 2000, the mortality of rural residents was higher than that of urban residents; it was during 2000 to 2005 that the mortality gap between urban and rural residents shrank rapidly, with mortality rates tending to be convergent with each other (Fig. 2). With few exceptions, later birth cohorts showed lower mortality.

Although comparisons of age-specific mortality are helpful for achieving some insight into age, period, and cohort effects, the obvious disadvantage of this approach is that it cannot distinguish these three effects simultaneously. In other words, the effects will be confounded, making reliable conclusions difficult to obtain [44]. In Fig. 1a, for a given year, the older age group is from an earlier birth cohort, thereby confounding the age and birth cohort effects. For a given age group, those alive in later years also belong to later birth cohorts, thereby confounding the period and cohort effects. Similarly, in Fig. 1b, for a given birth cohort, the older age group was also alive in later years, thereby confounding the age and period effects. For a given age group, the later birth cohorts were also alive in later years, thereby confounding the birth cohort and period effects. In Fig. 1a, b, it is because the age effects are confounded with the birth cohort and period effects respectively that we observe inconsistent age effects. In addition, although comparisons of age-specific mortality can provide a qualitative impression of age, period, and birth cohort effects, it is unable to provide a more accurate quantitative assessment [45].

Age, period, and birth cohort effects

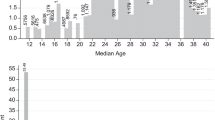

To distinguish the age, period, and cohort effects simultaneously, this study used the APC model (IE) to analyze infectious disease mortality trends (1990–2010) of Chinese urban and rural residents (5–84 years old). Table 1 shows the estimated coefficient, standard error, and other information. To compare the relative mortality risk across ages, periods, and birth cohorts, we calculated the exponential value of the estimated coefficients (exp(coef.) = ecoef.) (Table 1). Specifically, this value denotes the mortality relative risk (RR) of a particular age, period, or birth cohort relative to average levels [46, 47]. To grasp age, period, and cohort effect trends more intuitively, we plotted Fig. 3 based on the exponential value.

Age effects

The infectious disease mortality of Chinese residents is relatively high at age 5–9, reaches a minimum in adolescence (age group 10–19), then continues to rise with age, with the growth rate gradually slowing down from approximately age 75 (Fig. 3a). For example, among rural residents, the lowest mortality occurs at age group 15–19 and the risk decreases by 64 % (1–0.241/0.660 ≈ 0.635) compared with age group 5–9. Mortality RR then persistently increases by about 17 times (4.272/0.241–1 ≈ 16.726) until age group 80–84, with the growth rate of mortality declining from age group 70–74. Compared with urban residents, rural residents’ mortality rates at age group 5–9 were much higher than the minimum rate in adolescence, while the growth rate of mortality after age group 70–74 declined more significantly. As seen in Figs. 1a and 2, the mortality of children aged 5–9 in rural areas was higher than that of urban children before the year 2000, but this gap gradually disappeared after 2000. Before the year 2000, the mortality of rural residents aged 70–84 was higher than that of urban residents while an opposite trend started after 2000.

Period effects

From 1990 to 2000, the infectious disease mortality RR of Chinese residents declined rapidly, by 44 % (1–0.812/1.459 ≈ 0.443) in urban residents and 34 % (1–1.221/1.844 ≈ 0.338) in rural residents (Fig. 3b). From 2000 to 2005, there was a great difference in mortality trends between urban and rural residents, with urban mortality RR increasing by 14 % (0.923/0.812–1 ≈ 0.137) and rural mortality RR decreasing by 54 % (1–0.559/1.221 ≈ 0.542). As mentioned previously, it was during this period that the mortality gap between urban and rural residents substantially narrowed. From 2005 to 2010, the mortality of urban and rural residents declined though at a slower pace. By 2010, urban residents’ mortality was nearly equivalent to the value of year 2000, while the mortality RR of rural residents decreased by 59 % (1–0.498/1.221 ≈ 0.592) during this period.

Birth cohort effects

Among Chinese residents, later birth cohorts experienced lower infectious disease mortality, with the exception of some individual cohorts (Fig. 3c). From the 1906–1910 to the 1941–1945 birth cohorts, the decrease of mortality among urban residents was significantly faster than that of subsequent birth cohorts and rural counterparts (the mortality RR among urban residents declined by 68 % [1–1.087/3.353 ≈ 0.676] while that among rural counterparts declined by 42 % [1–1.311/2.255 ≈ 0.419]). It can be seen from Fig. 1a that the rapid decline in the mortality of urban cohorts is partly due to the combination of two factors: (1) the decline of urban mortality was mainly concentrated from 1990 to 2000; (2) the decline is more significant in middle-aged and elderly people and becomes more obvious with age. Thus, birth cohorts who were right at the middle-aged and elderly stage (namely, from 1906–1910 to 1941–1945 birth cohorts) experienced a more significant decline. For the 1946–1950 to 2001–2005 birth cohorts, the decline rates of urban mortality approached those of rural counterparts. For birth cohorts from 1906–1910 to 2001–2005, mortality RR of urban and rural residents decreased by 91 % (1–0.310/3.353 ≈ 0.908) and 83 % (1–0.375/2.255 ≈ 0.834), respectively.

Conclusions

In the current study, we analyzed infectious disease mortality trends (1990–2010) of urban and rural Chinese residents (5–84 years old) using the APC model and to estimate the age, period, and cohort effects simultaneously. The infectious disease mortality of Chinese residents is relatively high at age group 5–9, reaches a minimum in adolescence (age group 10–19), and then continues to rise with age, with the growth rate gradually slowing down from approximately age 75. The Chinese population is aging rapidly: from 2013 to 2050, the proportion of people aged over 60 will increase rapidly from 13.9 to 32.8 % while the proportion of people aged over 80 will increase from 1.6 to 6.5 % [48]. With the rapid aging of the Chinese population, the prevention and control of infectious disease in elderly people will present a greater challenge. Due to decreased immunity, malnutrition, physiological changes, and many other reasons, the elderly are not only more vulnerable to infectious diseases, but the diseases tend to be more severe and more difficult to treat [49–52]. Therefore, in addition to the prevention and control of infectious diseases in women and children, it is necessary to further strengthen screening, immunization, and treatment for the elderly at high risk.

From 1990 to 2010, the infectious disease mortality of Chinese residents has indeed experienced a substantial decline, except for a slight increase among urban residents from 2000 to 2005. This is largely due to the continuous improvement of living standards and the rapid development of health services. Factors including economic development, scientific and technological progress, as well as the government’s strong commitment and the establishment of an infectious disease surveillance and response system played an important role [4]. In contrast to the slight rise among urban residents during 2000 to 2005, the mortality of rural residents declined rapidly. It was during this period that the mortality gap between urban and rural residents substantially narrowed. This shows that the increased investment in rural health services [6] following the SARS outbreak in 2003 was indeed effective. It is especially worth noting that there was a nationwide expansion of Directly Observed Treatment, Short-Course from 2000 to 2005, which was quickly promoted after SARS [53]. During that period, the tuberculosis mortality rate in rural areas declined rapidly from 7.31/100,000 in 2000 to 2.89/100,000 in 2005 [7]. However, the slight increase in mortality among urban residents during 2000 to 2005 as well as the slowing pace of the decline in mortality among urban and rural residents from 2005 to 2010 indicate that the re-emergence of previously prevalent diseases and the emergence of new infectious diseases created new challenges for China’s prevention and control of infectious disease [4, 5]. Of course, this may be partly associated with the perfection of the infectious disease surveillance system in China [4, 54].

Among Chinese residents, later birth cohorts experienced lower infectious disease mortality. This may be largely due to the better living and health conditions of younger cohorts and their exposure at younger ages under these favorable circumstances [32, 34]. Meanwhile, for birth cohorts from 1906–1910 to 1941–1945, the decrease of mortality among urban residents was significantly faster than that of subsequent birth cohorts and rural counterparts. This is partly because the rapid decline in urban mortality more obviously benefited birth cohorts who were right at the middle-aged and elderly stage. Of course, it may also relate to advanced medical development and antibiotics usage during these birth cohorts’ early life [32]. Further studies are needed to fully understand this difference. Given that infectious disease mortality in older cohorts is still very high, in addition to the prevention and control of infectious disease in younger cohorts, it is necessary to further strengthen screening, immunization, and treatment for older cohorts at high risk. The rapid decline of mortality from 1906–1910 to 1941–1945 birth cohorts supports this viewpoint, and some recent studies also indicate that a prevention and control approach based on birth cohort can be cost-effective [55–57]. In the United States, the prevalence of hepatitis C is highest in the 1945–1965 birth cohorts, but many in these cohorts do not realize they are infected; these studies suggest they should be screened and treated.

Although we analyzed the age, period, and cohort effects of Chinese urban and rural residents’ infectious disease mortality, we could not further evaluate mortality trend differences by disease-specific or gender-specific due to data availability. This analysis is important because it can help clarify the factors that influence infectious disease trends and to locate people at high risk with greater accuracy [32]. For example, in contrast to tuberculosis and hepatitis B, AIDS mortality is higher at middle age, has grown steadily in recent years, and may be trending upward among younger birth cohorts [35]. Also, this analysis can help compare the results with those of existing studies on infectious diseases in China as well as studies in other countries. Meanwhile, further research should distinguish the internal difference in disease mortality trends of urban and rural residents. Since the reform and opening-up policyFootnote 2, the disparity within urban and rural areas continues to expand, and regional disparity is particularly worrisome [58]. This disparity makes a big difference in the ability of various regions to cope with disease, and is evident in the proportions of people who were ill but did not take any therapeutic measures within the last two weeks. In 2008, the proportion in big cities was 19.1 % while that in small cities was as high as 27.3 %; the proportion in first class rural areas was 28.5 % and that in fourth class rural areas was 35.5 % [12]. For residents who are from Central and Western regions, especially the rural areas of these regions, poverty is still an important factor threatening their health; conversely, diseases are also an important reason for their return to poverty [8].

Notes

Age effects refer to the risk differences between different age groups. As people age, changes in physiological status, social roles and life experiences will bring these differences. Period effects refer to the risk differences between different years. These differences reflect the changes of environment or the impact of historical events. Birth cohort effects refer to the risk between different birth cohorts. Different birth cohorts go through stages of life in different years and therefore different life trajectories bring them unique effects [32, 33].

It refers to the program of reforms called “socialism with Chinese characteristics” since 1978 and involves economic, political, cultural and other domains. In the economic domains, China has gradually established the socialist market economic system, and actively tried to attract foreign investment and develop foreign trade. In this process, the Chinese economy has achieved great achievements, but the gap between rich and poor has also been widening rapidly.

References

Hu LL, Hu AG. From unfair to fairer health development: the analysis and suggestions of Chinese urban and rural gap of disease pattern. Manage World. 2003;1:78–87.

Cook IG, Dummer TJB. Changing health in China: re-evaluating the epidemiological transition model. Health Policy. 2004;67(3):329–43.

Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, Gao GF, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):1987–2015.

Wang LD, Wang Y, Jin SG, Wu ZY, Chin DP, Koplan JP, et al. Emergence and control of infectious diseases in China. Lancet. 2008;372(9649):1598–605.

Zhang L, Wilson DP. Trends in notifiable infectious diseases in China: implications for surveillance and population health policy. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31076.

United Nations Development Programme. China human development report 2007–2008. Beijing: China Translation and Publishing Corporation; 2008.

National Health and Family Planning Commission. China health and family planning yearbook 2013. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Press; 2013.

Liu YL, Rao KQ, Hsiao WC. Medical expenditure and rural impoverishment in China. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003;21(3):216–22.

Dummer TJB, Cook IG. Exploring China’s rural health crisis: Processes and policy implications. Health Policy. 2007;83(1):1–16.

Hu S, Tang S, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Escobar ML, de Ferranti D. Reform of how health care is paid for in China: challenges and opportunities. Lancet. 2008;372:1846–53.

Tang SL, Meng QY, Chen L, Bekedam H, Evans T, Whitehead M. Tackling the challenges to health equity in China. Lancet. 2008;372(9648):1493–501.

Center for Health Statistics and Information, Ministry of Health. An Analysis Report of National Health Services Survey in China, 2008. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.cn/cmsresources/mohwsbwstjxxzx/cmsrsdocument/doc9911.pdf.

Qian ZH. Risk of HIV/AIDS in China: subpopulations of special importance. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(6):442–7.

Lu L, Jia MH, Ma YL, Yang L, Chen ZW, Ho DD, et al. The changing face of HIV in China. Nature. 2008;455(7213):609–11.

Wang N, Wang L, Wu Z, Guo W, Sun X, Poundstone K, et al. Estimating the number of people living with HIV/AIDS in China: 2003–09. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(Supplement 2):ii21–8.

Jia Z, Wang L, Chen RY, Li D, Wang L, Qin Q, et al. Tracking the evolution of HIV/AIDS in China from 1989–2009 to inform future prevention and control efforts. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25671.

Zhang L, Chow EPF, Jing J, Zhuang X, Li X, He M, et al. HIV prevalence in China: integration of surveillance data and a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(11):955–63.

Chen XS, Gong XD, Liang GJ, Zhang GC. Epidemiologic trends of sexually transmitted diseases in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27(3):138–42.

Lin CC, Gao X, Chen X, Chen Q, Cohen MS. China’s syphilis epidemic: a systematic review of seroprevalence studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(12):726–36.

Chen Z, Zhang G, Gong X, Lin C, Gao X, Liang G, et al. Syphilis in China: results of a national surveillance programme. Lancet. 2007;369(9556):132–8.

Cui F, Hadler SC, Zheng H, Wang F, Zhenhua W, Yuansheng H, et al. Hepatitis A surveillance and vaccine use in China from 1990 through 2007. J Epidemiol. 2009;19(4):189–95.

Liang X, Bi S, Yang W, Wang L, Cui G, Cui F, et al. Epidemiological serosurvey of hepatitis B in China—declining HBV prevalence due to hepatitis B vaccination. Vaccine. 2009;27(47):6550–7.

Duan Z, Jia J, Hou J, Lou L, Tobias H, Xu XY, et al. Current challenges and the management of chronic hepatitis C in mainland China. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(8):679–86.

China Tuberculosis Control Collaboration. The effect of tuberculosis control in China. Lancet. 2004;364(9432):417–22.

Yang X, Li Y, Mei Y, Yu Y, Xiao J, Luo J, et al. Time and spatial distribution of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among Chinese people, 1981–2006: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(10):e828–37.

Wang L, Zhang H, Ruan Y, Chin DP, Xia Y, Cheng S, et al. Tuberculosis prevalence in China, 1990–2010: a longitudinal analysis of national survey data. Lancet. 2014;383(9934):2057–64.

Si H, Guo Z, Hao Y, Liu Y, Zhang D, Rao S, et al. Rabies trend in China (1990–2007) and post-exposure prophylaxis in the Guangdong province. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:113.

Song M, Tang Q, Rayner S, Tao X, Li H, Guo Z, et al. Human rabies surveillance and control in China, 2005–2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:212.

Xu ZW, Hu WB, Zhang YW, Wang XF, Tong SL, Zhou MG. Spatiotemporal pattern of bacillary dysentery in China from 1990 to 2009: what is the driver behind? PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104329.

Deng T, Huang Y, Yu SC, Gu J, Huang CR, Xiao GX, et al. Spatial-temporal clusters and risk factors of hand, foot and mouth disease at the district level in Guangdong province, China. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56943.

Xing WJ, Liao QH, Viboud C, Zhang J, Sun JL, Wu JT, et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease in China, 2008–12: an epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:308–18.

Yang Y. Trends in U.S. adult chronic disease mortality, 1960–1999: age, period, and cohort variations. Demography. 2008;45(2):387–416.

Reither EN, Hauser RM, Yang Y. Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of the obesity epidemic in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1439–48.

Collins JJ. The contribution of medical measures to the decline of mortality from respiratory tuberculosis: an age-period-cohort model. Demography. 1982;19(3):409–27.

Castilla J, Pollan M, Lopez-Abente G. The AIDS epidemic among Spanish drug users: a birth cohort-associated phenomenon. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(5):770–4.

Wu P, Cowling BJ, Schooling CM, Wong IOL, Johnston JM, Leung C, et al. Age-period-cohort analysis of tuberculosis notifications in Hong Kong from 1961 to 2005. Thorax. 2008;63(4):312–6.

Chung RY, Leung GM, Cowling BJ, Schooling CM. Patterns of and hypotheses for infection-related cancers in a Chinese population with rapid economic development. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140(10):1904–19.

Fu WJ. Ridge estimator in singular design with application to age-period-cohort analysis of disease rates. Commun Stat-Theory Method. 2000; 29: 263–78.

Yang Y, Fu WJ, Land KC. A methodological comparison of age-period-cohort models: the intrinsic estimator and conventional generalized linear models. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34(1):75–110.

Yang Y, Schulhofer-Wohl S, Fu WJ, Land KC. The intrinsic estimator for age-period-cohort analysis: what it is and how to use it. Am J Sociol. 2008;113(6):1697–736.

Yang Y. Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: an age-period-cohort analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 2008;73(2):204–26.

Mason WM, Mason KO, Winsborough HH, Poole WK. Some methodological issues in cohort analysis of archival data. Am Sociol Rev. 1973;38(2):242–58.

Fienberg SE, Mason WM. Identification and estimation of age-period-cohort models in the analysis of discrete archival data. Sociol Methodol. 1979;10:1–67.

Holford TR. Understanding the effects of age, period, and cohort on incidence and mortality rates. Annu Rev Public Health. 1991;12:425–57.

Kupper LL, Janis JM, Karmous A, Greenberg BG. Statistical age-period-cohort analysis: a review and critique. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(10):811–30.

Keyes KM, Miech R. Age, period, and cohort effects in heavy episodic drinking in the US from 1985 to 2009. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1–2):140–8.

Phillips JA. A changing epidemiology of suicide? The influence of birth cohorts on suicide rates in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2014;114:151–60.

United Nations. World population prospects: the 2012 revision. Available at: http://esa.un.org/wpp/.

Gavazzi G, Krause K. Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(11):659–66.

Casau NC. Perspective on HIV infection and aging: Emerging research on the horizon. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(6):855–63.

Blanco JR, Caro AM, Pérez-Cachafeiro S, Gutiérrez F, Iribarren JA, González-García J, et al. HIV infection and aging. AIDS Rev. 2010;12(4):218–30.

Asahina Y, Tsuchiya K, Tamaki N, Hirayama I, Tanaka T, Sato M, et al. Effect of aging on risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2010;52(2):518–27.

Wang L, Liu J, Chin DP. Progress in tuberculosis control and the evolving public-health system in China. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):691–6.

Hipgrave D. Communicable disease control in China: From Mao to now. J Glob Health. 2011;1(2):224–38.

McGarry LJ, Pawar VS, Panchmatia HR, Rubin JL, Davis GL, Younossi ZM, et al. Economic model of a birth cohort screening program for hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2012;55(5):1344–55.

Rein DB, Smith BD, Wittenbom JS, Lesesne SB, Wagner LD, Roblin DW, et al. The cost-effectiveness of birth-cohort screening for Hepatitis C antibody in US primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(4):224–63.

Liu S, Cipriano LE, Holodniy M, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD. Cost-effectiveness analysis of risk-factor guided and birth-cohort screening for chronic Hepatitis C infection in the United States. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58975.

Li Z, Wang PG. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Objective Quality of Life of Chinese Residents: 2006 to 2009. Soc Indic Res. 2013;113(3):1075–90.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Xiaoling Wu, officer in National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China, for her data providing assistant to this study. We would also like to thank Professor Xiaohong Zhou at Nanjing University for the inspiration of his reading group, as well as Professor Yuxiao Wu for his valuable comments on the earlier drafts of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZL: conception and design of the study, statistical analysis, drafts and revision of the manuscript. PW: conception and design of the study, data collection and statistical analysis, critical review of the manuscript. GG: statistical analysis, interpretation of the results, critical revision of the manuscript. CX: contribution to data collection and review of the manuscript. XC: contribution to design of the study and critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Wang, P., Gao, G. et al. Age-period-cohort analysis of infectious disease mortality in urban-rural China, 1990–2010. Int J Equity Health 15, 55 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0343-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0343-7