Abstract

Background

The obesity prevalence in children and adolescents has increased worldwide during the past 30 years. Although diet has been identified as one risk factor for developing obesity in this age group, the role of specific dietary factors is still unclear. One way to gain insight into the role of these factors might be to detect biomarkers that reflect metabolic health and to identify the associations between dietary factors and these biomarkers. This would enable nutrition-related metabolic changes to be detected early in life, which might be a promising strategy to prevent childhood obesity. However, existing literature offers only inconclusive evidence for diet and some of these obesity-related biomarkers (e.g., blood lipids). We thus conducted a systematic literature review to further examine eligible studies that investigate associations between dietary factors and 12 obesity-related biomarkers in healthy children and adolescents aged 3-18 years.

Methods

We searched the scientific databases PubMed/Medline and Web of Science Core Collection for potentially eligible articles. Our final literature search resulted in 2727 hits. After the selection process, we included 81 articles that reported on 1111 single observations on dietary factors and any of the obesity-related biomarkers.

Results

Around 81% of the total observations showed nonsignificant results. For many biomarkers we did not find enough observations to draw clear conclusions on possible associations between a dietary factor and the respective biomarker. In cases where we identified enough observations, the results were contradictory. Since these nonsignificant and inconclusive findings may impede the development of effective strategies against childhood obesity, this article takes a closer look at possible reasons for such findings. In addition, it provides action points for future research efforts.

Conclusions

In conclusion, current evidence on associations between dietary factors and obesity-related biomarkers is inconclusive. We thus provided an overview on which specific limitations may impede current research. Such knowledge is necessary to enable future research efforts to better elucidate the role of diet in the early stages of obesity development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The obesity prevalence in children and adolescents has increased worldwide during the past 30 years [1, 2]. According to the BMI cut-off-points of the International Obesity Task Force worldwide about 10% (155 million) of children and adolescents aged 5-17 years old were estimated to be overweight in 2004 [3, 4]. Moreover, among those 2-3% (30-45 million) were estimated to be obese [4, 5]. In the pediatric age group, obesity is associated with significant health consequences, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and diabetes [1, 2]. Furthermore, it is an important risk factor for adult morbidity and mortality [6].

Diet is considered to play a key role in obesity development [7], and researchers worldwide have undertaken efforts to clarify the role of specific dietary factors in the complex etiology of obesity [8]. However, it is still unclear which nutrients and foods contribute to the development of obesity in children and adolescents [9]. This might be one reason for the limited success of existing obesity prevention strategies, as these strategies mainly focus on dietary behavior either alone or in combination with physical activity [10, 11].

One strategy to obtain new insights into the complex role diet is playing in obesity development may be the identification of biological markers that reflect metabolic health. Determining associations between dietary factors and such biomarkers could be helpful in detecting nutrition-related metabolic changes early in life, thus providing new pathways in the fight against obesity.

Former literature reviews already focused on some of these biomarkers. For example, a systematic review investigated associations between protein intake and three biomarkers of cardiovascular health: blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, and blood lipids in children [12]. The authors concluded the current evidence between protein intake and these cardiovascular biomarkers to be inconclusive. In addition, a narrative review on the impact of diet on cardiovascular health revealed that results were inconsistent even for those dietary factors that were studied most, such as fast food and sugar-sweetened beverages [13]. The results of these reviews indicate that various factors such as measurement errors may exist that obscure the true associations between diet and obesity-related biomarkers in the age group of children and adolescents. We therefore decided to conduct a systematic literature review to further examine eligible studies that focus on associations between diet and 12 obesity-related biomarkers in healthy children and adolescents aged 3-18 years. We aimed to: a) expand the findings of former literature reviews, b) examine, if we can confirm the inconclusive findings of these reviews, and c) if yes, take a closer look on possible reasons for those inconclusive findings.

Methods

Literature search

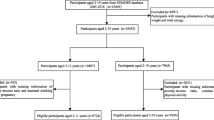

We conducted our systematic literature review in accordance to the PRISMA Statement [14]. We searched the scientific databases PubMed/Medline and Web of Science Core Collection (WoS CC) for potentially eligible articles. We developed a systematic search strategy, which included the following Medical Subject Heading terms from PubMed: “child”, “adolescent”, “food and beverages”, “diet” “food quality”, “triglycerides”, “blood glucose”, “blood pressure”, and “C-reactive protein”. In addition, we took into account free-text terms like “dietary intake” and “biomarker”. For the WoS CC database we adapted our final PubMed search strategy. In Additional file 1 we provide the exact search strategies of both literature databases. The final screen on 2016/02/29 resulted in 2727 hits (Fig. 1) from both databases after excluding 335 duplicates identified via Endnote software (Thomson Reuters).

Study selection

Table 1 provides an overview of the a priori defined inclusion and exclusion criteria that we applied to select eligible articles. The exposure variable was a dietary factor (macronutrient, single food, dietary pattern). The outcomes of interest were obesity-related biomarkers (Table 1), which we had previously derived from two existing literature reviews that investigated associations between biomarkers and obesity in children and adolescents [8, 15]. Barkin, et al. [15] revealed that biomarkers related to obesity in adults (e.g., cortisol) did not show such associations in children. We therefore took only those biomarkers into account that were associated with obesity in children.

Three of the authors (JHK, IM, CB) independently screened all 2727 abstracts. By applying inclusion/exclusion criteria to the information contained in the abstract, we reduced the pool of potentially eligible articles to 316 (Fig. 1). The same three authors also evaluated the retrieved full-text articles applying the same inclusion and exclusion criteria that were used for the abstract selection. Any disagreements during the selection process were discussed among all three reviewers since consensus was reached. Finally we included 81 full-text articles into our review.

Data extraction, data elements, and quality assessment

Three of the authors (JHK, IM, CB) extracted relevant information from all 81 articles using a standardized data extraction template. We designed our template with the intent of shedding light on possible reasons for inconclusive findings. Thus we included detailed information on food/nutrient intake (e.g., assessment method, nutrient databases) and biomarkers (e.g., assessment method, blood collection procedures), in addition to general information on study design and characteristics of the study population (e.g., recruitment methods, sample size). We also extracted from each article details on data analyses (e.g., statistical methods, adjustment for confounders) and relevant information to evaluate a potential risk of bias.

Study quality was assessed by two of the authors (JHK, CB) independently. We slightly adapted a quality assessment tool that was originally developed by Voortman, et al. [12] to evaluate study quality of all articles included in our review. The quality assessment tool used a rating scheme ranging from low to high (low quality: 0-4, moderate quality: 5-8, high quality: 9-11). We took into account the following characteristics to rate the study quality: study design, sample size, intake validity, adjustment for potential confounders, and the occurrence of a selection bias (Additional file 2). We decided to use this assessment tool because it takes criteria into account that are unique for nutrition studies (e.g., the validity of the dietary assessment) and thus are not reflected by the standard tools. As measurement error in dietary intake assessment might also be on potential explanation for inconclusive findings we preferred the tool introduced by Voortman et al. 2015 to quality assessment tools conventionally used in systematic reviews.

Data preparation

Two of the authors (CB, JHK) rechecked a random sample of all data extracted to ensure high data quality. Afterwards, we prepared data for descriptive data analyses. In some cases, we extracted multiple subentries (from now on labeled as observations) from one article because they reported one value for the total study sample and, for example, additional values for either males or females. In such cases, we decided to exclude the overall value from further analyses to avoid double counting of individuals. In addition, several articles reported on associations between a dietary factor and more than one biomarker (e.g., blood pressure, total cholesterol) or on associations between different dietary factors (e.g., vegetables, dairy products, sweets) and one biomarker. In these cases, we kept multiple observations from one article in the descriptive analyses as these observations provided separate information of interest.

Data analyses

We conducted descriptive analyses to give an overview of the main characteristics of all articles included (see Additional file 3 for a detailed overview of the characteristics of each single study). Due to heterogeneity of the articles with regard to, for example, study designs, dietary assessment methods, and statistical analyses, we decided that conducting a formal meta-analysis was not appropriate. Instead we provide a descriptive summary of our results.

Results

We included a total of 81 articles with an overall sample size of 52,764 (sample sizes range: 79-21,111). The majority of articles (79.0%) had a cross-sectional design. Most articles assessed dietary intake using food frequency questionnaires (FFQs; 38.3%), followed by 37.0% of articles that used 24-h recalls. Following our quality assessment tool we rated more than half of the articles (58.0%) low in quality and only 3.7% achieved a high quality score (Table 2).

The 81 articles reported on 1111 single observations of associations between a dietary factor and a biomarker of interest. Figure 2 shows the number of observations found for each biomarker of interest (besides Adiponectin, where no observations could be identified). We identified most observations for systolic blood pressure (n = 149), followed by observations on total cholesterol (n = 143), diastolic blood pressure (n = 139), and Homeostatic Model Assessment (HOMA)-insulin resistance (n = 135). Overall, 19.2% of all 1111 observations found significant associations between a dietary factor and any of the obesity-related biomarkers considered. Figure 2 also provides an overview on the percentage of significant associations separated by biomarker. In relative terms, we observed the highest percentage of significant associations for C-reactive protein (CRP; 35.5%) followed by fasting triglycerides (31.1%), and fasting insulin (25.0%). For all other biomarkers the number of significant associations observed was below 20.0% (Fig. 2). A separate consideration of 180 observations (18 articles) that examined associations between dietary patterns and obesity- related biomarkers revealed that 17.2% (n = 31) of these observations were significant.

As mentioned above we observed the highest percentage of significant associations for CRP. Table 3 provides a brief overview of all observations (n = 62) found between dietary factors and CRP levels. Overall, these observations came from 13 articles that reported on 31 different dietary factors. For most of these dietary factors, only one or two observations were available that reported on possible associations between CRP and the respective dietary factor. In cases where we identified more than two observations, results were inconsistent. For example, Aeberli et al. 2006 [16] found a significant association between fat and CRP levels (β = 0.28; p = 0.007). In contrast, Thomas et al. 2008 [17] did not find such an association, neither for girls (r = 0.05; p = 0.705) nor for boys (r = −0.25; p = 0.053). For some associations, we also observed sex differences (e.g., for whole grains [18]).

We also saw such inconsistencies for systolic blood pressure, the biomarker with most observations found. About 16.0% of all 149 observations identified (Fig. 2), showed a significant association between a dietary factor and systolic blood pressure. For example, we found six observations (derived from three articles: [19,20,21]) that examined associations between sugar sweetened beverages and systolic blood pressure. While four of these six observations showed nonsignificant results, two observations reported a positive association between sugar sweetened beverages and systolic blood pressure ([20, 21]; Additional file 3). However, while Bremer et al. 2009 [20] reported a significant association for girls only (β = 0.38; p < 0.05), Chan et al. 2009 [21] found such an association for boys (β = 1.6; p < 0.043) but not for girls (β = 0.8; p = 0.171). We saw a similar inconsistent picture for all other biomarkers of interest (Additional file 3).

Discussion

Summary of main findings and comparison with previous reviews

Our systematic review revealed that only a minority (19.2%) of the total observations showed significant associations between a dietary factor and any of the obesity-related biomarkers included. Furthermore, for many biomarkers we were not able to identify enough observations to draw clear conclusions on possible associations between a dietary factor and the respective biomarker. Our results confirm the findings of existing reviews [12, 13]. Since nonsignificant and inconclusive findings may impede the development of effective strategies against childhood obesity, we decided to take a closer look at possible reasons for these findings.

Possible reasons for the nonsignificant and inconclusive findings in our review

Dietary intake

The common approach to studying diet-disease relationships focuses on single nutrients or food items. One major criticism of this approach is that typical diets do not consist of single nutrients or foods: indeed, these items are eaten in combination [22]. Another shortcoming of this approach is that the effect of a single nutrient might be too small to detect [22]. Therefore, an examination of dietary patterns has been suggested because these patterns may reflect the complexity of the diet better than single nutrients or food items [23]. In addition, Hu suggested that the cumulative effects of multiple nutrients or food items reflected by a dietary pattern might be large enough to be detected [22]. However, at least in our review, taking into account only observations on dietary patterns did not change the results.

Measurement errors in dietary intake assessment

Nutrition epidemiology is also affected by bias resulting from imprecision in the measurement of dietary intake [24]. Measurement error may cause over- or underestimation of the impact of exposure [24]. Thus the accurate assessment of dietary intake in children and adolescents is essential not only to monitor nutritional status but also to draw reliable conclusions on diet-disease relationships within this age group [25]. However, valid assessment of dietary intake can be particularly difficult for this age group [26]. Children younger than 8 years do not have the cognitive abilities to report their dietary intake [27]. Therefore, involving proxy respondents like parents or other caregivers is necessary to obtain information on children’s dietary intake [27]. Overall, 43.2% of all articles included in our review reported the involvement of parents in dietary intake assessment. In the youngest age group (three- to seven-year-old children), the percentage was even higher, with more than 75% of articles stating that parents assisted in dietary intake assessment. However, parents often do not know what their children have consumed when the children are supervised by other persons, for example, by their teachers at school [28]. Another issue in the assessment of dietary intake is the estimation of portion sizes: most children, in addition to lacking the cognitive abilities necessary to accurately report portion sizes, simply do not pay attention to frequencies and portion sizes while they are eating [27]. Among adolescents valid reporting of dietary intakes is affected by unstructured eating patterns, increased out-of-home eating, and lack of motivation [27]. Another possibility of measurement error is the dietary assessment method itself. Although 24-h recalls, FFQs, and dietary records are the common methods to assess dietary intake, their accuracy and appropriateness in the age group of children has been questioned [29]. A current systematic review indicates that the FFQ might be the most appropriate method to assess dietary intake in children aged 11 years and younger [29]. However, the authors concluded that further research on the validity and reliability of dietary assessment methods in children is needed due to a limited generalizability of the results.

Moreover, current dietary assessment methods are prone to social desirability bias [13]. Underreporting of foods considered as unhealthy (e.g., sugar-sweetened beverages) and overreporting of foods perceived as healthy (e.g., fruits and vegetables) might be another reason why we do not find consistent associations between a dietary factor and the obesity-related biomarkers included. Archer et al. [30] examined the issue of dietary reporting error in different waves of the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). They found that the self-reported energy intakes were implausible for more than half of all participants [30]. Moreover, a large European multicenter study in children and infants revealed that parental underreporting was strongly affected by parental concerns/perceptions of their child’s weight status [31].

Biomarkers

Furthermore, it may be that inappropriate biomarkers are being measured in children. For example, there might be differences in the metabolism of nutrients between children and adults. Kostyak, et al. [32] reported that, compared to adults, pre-pubertal children oxidize greater amounts of fat per calorie expended each day. Such differences in metabolism may also exist for other nutrients, and thus the age group might be too young to observe associations between dietary intake and the biomarkers considered in our review. Another explanation might be that metabolic consequences may not occur before early adulthood because children and adolescents may cope with an unbalanced diet better than adults can. Former studies indicate that puberty seems to influence biomarker levels. For example, HDL cholesterol levels have been found to be higher among girls at pubertal stage compared to boys [33, 34]. This may explain sex differences that we observed for some of the diet-biomarker associations. In addition, it is important that these differences are taken into account in statistical analyses by conducting separate analyses for girls and boys or at least by adjusting the analyses for the pubertal stage.

Measurement errors at the biomarker level

In contrast to the measurement of dietary intake, subjective reporting errors like social desirability bias are not affecting biomarkers [35]. However, biomarker measurements are not free of error. For example, blood sampling techniques, storage procedures, and laboratory assay errors can influence the results [36]. In addition, biomarker levels may vary over time within an individual; a single biomarker measurement, as common in many epidemiological studies [36], may thus not be able to reflect long-term consequences of diet. Another shortcoming of biomarker measurement is determining adequate reference values for the age group of children and adolescents [37]. For example, there are currently four methods used to determine insulin levels: bioassays, high-performance liquid chromatography, stable isotope dilution mass spectrometry assay, and immunoassays [37]. However, separate reference values for the pediatric population have not been defined for any of these methods [37]. As discussed above, growth and pubertal stage may affect biomarkers in this age group, making the establishment of reference intervals for children and adolescents a major challenge [37].

Study quality

Another reason why we did not find clear associations between dietary factors and the obesity-related biomarkers may be related to study quality. The majority of the studies included (58.0%) were rated low in quality, mainly because few articles considered important confounding factors like energy intake and body weight. This finding is in line with the review by Voortman, et al. [12] on protein intake and cardiovascular health.

In our review the low sample sizes reported in the majority of articles (56.8%) may not have allowed an adequate adjustment for potential confounders in most studies included. Furthermore, these low sample sizes may have resulted in a low statistical power and thus may have reduced the chance of detecting significant associations. In addition, most of the articles included in our review reported on cross-sectional studies. As long-term exposure to unbalanced diets and not eating a single unhealthy meal causes diet-related diseases, cross-sectional studies may not be able to adequately reflect the adverse health effects of unbalanced diets [38].

Action points for the future

Longitudinal studies in particular should be conducted to obtain information on long-term consequences of dietary intake on obesity-related biomarkers in children and adolescents. In addition, large sample sizes are necessary to ensure adequate adjustment for important confounding factors such as: sex, age, energy intake and anthropometric measurements. In addition, other confounding factors include: pubertal stage, sex hormones, parental overweight, physical activity, and socioeconomic status.

The development of novel dietary assessment methods for children and adolescents or at least a refinement of existing methods is necessary and should take into account age, cognitive abilities, and adequate tools for portion size estimation [27]. In addition, tools to assess dietary intake in adolescents should be less burdensome and more able to motivate young people, as a lack of motivation in reporting dietary intake seems to exist in this age group [27]. As the age group of adolescents is very computer literate, smartphone applications for assessing dietary intake may greatly improve dietary intake reporting within that age group [27]. Furthermore, we also need better reporting on the details of dietary assessment. For example, a statement on the validity of the dietary assessment method used should be given. Moreover, it is important that novel dietary assessment methods reflect the usual diet of an individual and not merely provide a snapshot of what an individual has eaten during a single day or week. Smartphone technologies may be helpful in collecting long-term data on dietary intake without too much effort for the individual.

In addition, novel biomarkers that better reflect dietary intake in the age group of children and adolescents are necessary [35]. These biomarkers should be valid, noninvasive, cost-effective, and able to reflect changes in dietary intake over time [35]. Moreover, they should enable researchers and health professionals to detect early on children that have an increased risk of becoming overweight or obese. Kuhnle suggested to analyze hair specimens as an alternative to the current blood sample analyses, due to its ability to reflect long-term diet [39]. The emerging field of metabolomics may also be helpful in discovering novel biomarkers [35]. Current metabolomic screenings identified urinary markers that are associated with the consumption of a specific food or food groups [40]. For example, researchers found urinary markers reflecting the intake of oily fish, a meat-rich diet, and a vegetable-rich diet [40]. Furthermore, metabolomics may be helpful in validating the findings from observational or epidemiological studies in the future [41].

Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of our literature review include the application of a systematic search strategy and adherence to PRISMA guidelines [14]. Furthermore, we searched for eligible studies in two of the most renowned biomedical literature databases, which also decreased the probability of missing relevant articles. However, as we only included peer-reviewed articles we cannot fully exclude the occurrence of a publication bias. In addition, a language bias may have affected our results as we only took English-language articles into account. Nevertheless, our literature review provides valuable insights into possible reasons for the nonsignificant and inconclusive findings with regard to associations between dietary factors and obesity-related biomarkers in the age group of children and adolescents.

Conclusions

Our systematic review confirmed that associations between diet and obesity-related biomarkers are nonsignificant and inconclusive. We thus focused on possible reasons for these inconclusive findings because they may impede the development of effective strategies against childhood obesity. We provided action points for future research efforts, such as improving dietary intake assessment in children and adolescents and identifying appropriate obesity-related biomarkers. Such research efforts are urgently needed to clarify the role of diet in early stages of obesity development and may enable the implementation of evidence-based interventions to prevent childhood obesity.

Abbreviations

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- HOMA-IR::

-

Homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- WoS CC:

-

Web of Science Core Collection

References

Han J, Lawlor D, Kimm S. Childhood obesity – 2010: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2010;375:1737–48.

Velazquez-Lopez L, Santiago-Diaz G, Nava-Hernandez J, Munoz-Torres AV, Medina-Bravo P, Torres-Tamayo M. Mediterranean-style diet reduces metabolic syndrome components in obese children and adolescents with obesity. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:175.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–3.

Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev. 2004;5(Suppl 1):4–104.

Ahmad QI, Ahmad CB, Ahmad SM. Childhood obesity. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2010;14:19–25.

Cali AM, Caprio S. Obesity in children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:S31–6.

O'Sullivan A, Gibney MJ, Brennan L. Dietary intake patterns are reflected in metabolomic profiles: potential role in dietary assessment studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:314–21.

Pate RR, O'Neill JR, Liese AD, Janz KF, Granberg EM, Colabianchi N, et al. Factors associated with development of excessive fatness in children and adolescents: a review of prospective studies. Obes Rev. 2013;14:645–58.

Ambrosini GL. Childhood dietary patterns and later obesity: a review of the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;73:137–46.

Summerbell CD, Waters E, Edmunds LD, Kelly S, Brown T, Campbell KJ. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2005:CD001871.

Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, Brown T, Campbell KJ, Gao Y, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011:CD001871.

Voortman T, Vitezova A, Bramer WM, Ars CL, Bautista PK, Buitrago-Lopez A, et al. Effects of protein intake on blood pressure, insulin sensitivity and blood lipids in children: a systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:383–402.

Funtikova AN, Navarro E, Bawaked RA, Fito M, Schroder H. Impact of diet on cardiometabolic health in children and adolescents. Nutr J. 2015;14:118.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–41.

Barkin S, Rao Y, Smith P, Po'e E. A novel approach to the study of pediatric obesity: a biomarker model. Pediatr Ann. 2012;41:250–6.

Aeberli I, Molinari L, Spinas G, Lehmann R, l'Allemand D, Zimmermann MB. Dietary intakes of fat and antioxidant vitamins are predictors of subclinical inflammation in overweight Swiss children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:748–55.

Thomas NE, Baker JS, Graham MR, Cooper SM, Davies B. C-reactive protein in schoolchildren and its relation to adiposity, physical activity, aerobic fitness and habitual diet. Br J Sports Med. 2008;2008:42.

Hur IY, Reicks M. Relationship between whole-grain intake, chronic disease risk indicators, and weight status among adolescents in the National Health and nutrition examination survey, 1999-2004. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:46–55.

Ambrosini GL, Oddy WH, Huang RC, Mori TA, Beilin LJ, Jebb SA. Prospective associations between sugar-sweetened beverage intakes and cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:327–34.

Bremer AA, Auinger P, Byrd RS. Relationship between insulin resistance-associated metabolic parameters and anthropometric measurements with sugar-sweetened beverage intake and physical activity levels in US adolescents: findings from the 1999-2004 National Health and nutrition examination survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:328–35.

Chan TF, Lin WT, Huang HL, Lee CY, Wu PW, Chiu YW, et al. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome in adolescents. Nutrients. 2014;6:2088–103.

Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:3–9.

Fung TT, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Rifai N, Tofler GH, Willett WC, Hu FB. Association between dietary patterns and plasma biomarkers of obesity and cardiovascular disease risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:61–7.

Marshall JR. Methodologic and statistical considerations regarding use of biomarkers of nutritional exposure in epidemiology. J Nutr. 2003;133:881–7.

Livingstone MB, Robson PJ, Wallace JM. Issues in dietary intake assessment of children and adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:213–22.

Burrows TL, Martin RJ, Collins CE. A systematic review of the validity of dietary assessment methods in children when compared with the method of doubly labeled water. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1501–10.

Livingstone MB, Robson PJ. Measurement of dietary intake in children. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:279–93.

Foster E, Adamson A. Challenges involved in measuring intake in early life: focus on methods. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;73:201–9.

Olukotun O, Seal N. A systematic review of dietary assessment tools for children age 11 years and younger. ICAN. 2015;7:139–47.

Archer E, Hand GA, Blair SN. Validity of U.S. nutritional surveillance:National Health and nutrition examination survey caloric energy intake data, 1971-2010. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76632.

Bornhorst C, Huybrechts I, Ahrens W, Eiben G, Michels N, Pala V, et al. Prevalence and determinants of misreporting among European children in proxy-reported 24 h dietary recalls. Br J Nutr. 2013;109:1257–65.

Kostyak JC, Kris-Etherton P, Bagshaw D, DeLany JP, Farrell PA. Relative fat oxidation is higher in children than adults. Nutr J. 2007;6:19.

LaRosa JC. Lipids and cardiovascular disease: do the findings and therapy apply equally to men and women? Womens Health Issues. 1992;2:102–11. discussion 111-103

Truthmann J, Richter A, Thiele S, Drescher L, Roosen J, Mensink GB. Associations of dietary indices with biomarkers of dietary exposure and cardiovascular status among adolescents in Germany. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2012;9:92.

Hedrick VE, Dietrich AM, Estabrooks PA, Savla J, Serrano E, Davy BM. Dietary biomarkers: advances, limitations and future directions. Nutr J. 2012;11:109.

Tworoger SS, Hankinson SE. Use of biomarkers in epidemiologic studies: minimizing the influence of measurement error in the study design and analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:889–99.

Shaw JL, Binesh Marvasti T, Colantonio D, Adeli K. Pediatric reference intervals: challenges and recent initiatives. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2013;50:37–50.

van Ommen B, Keijer J, Heil SG, Kaput J. Challenging homeostasis to define biomarkers for nutrition related health. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009;53:795–804.

Kuhnle GG. Nutritional biomarkers for objective dietary assessment. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:1145–9.

Astarita G, Langridge J. An emerging role for metabolomics in nutrition science. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2013;6:181–200.

Jenab M, Slimani N, Bictash M, Ferrari P, Bingham SA. Biomarkers in nutritional epidemiology: applications, needs and new horizons. Hum Genet. 2009;125:507–25.

Au LE, Economos CD, Goodman E, Houser RF, Must A, Chomitz VR, et al. Dietary intake and cardiometabolic risk in ethnically diverse urban schoolchildren. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:1815–21.

Chan She Ping-Delfos WL, Beilin LJ, Oddy WH, Burrows S, Mori TA. Use of the dietary guideline index to assess cardiometabolic risk in adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:1741–52.

Gonzalez-Gil EM, Santabarbara J, Russo P, Ahrens W, Claessens M, Lissner L, et al. Food intake and inflammation in European children: the IDEFICS study. Eur J Nutr. 2015;55(8):2459–68.

Holt EM, Steffen LM, Moran A, Basu S, Steinberger J, Ross JA, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and its relation to markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:414–21.

Kosova EC, Auinger P, Bremer AA. The relationships between sugar-sweetened beverage intake and cardiometabolic markers in young children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:219–27.

Lin Y, Huybrechts I, Vereecken C, Mouratidou T, Valtuena J, Kersting M, et al. Dietary fiber intake and its association with indicators of adiposity and serum biomarkers in European adolescents: the HELENA study. Eur J Nutr. 2014;54(5):771–82.

Qureshi MM, Singer MR, Moore LL. A cross-sectional study of food group intake and C-reactive protein among children. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2009;6:40.

Vyncke KE, Huybrechts I, Dallongeville J, Mouratidou T, Van Winckel MA, Cuenca-Garcia M, et al. Intake and serum profile of fatty acids are weakly correlated with global dietary quality in European adolescents. Nutrition. 2013;29:411–9. e411-413

Zhu Y, Wang H, Hollis JH, Jacques PF. The associations between yogurt consumption, diet quality, and metabolic profiles in children in the USA. Eur J Nutr. 2014;54(4):543–50.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Volker Braun and Maurizio Grilli from the library of the Medical Faculty Mannheim for their valuable assistance in developing the search strategy and adapting the Pubmed search to the WoS CC database. We also thank Benedict Katzenberger (Mannheim Institute of Public Health) and Tabea Becker-Gruenig (Department of Pediatrics, University Medicine Mannheim) for their assistance in data processing. In addition, we acknowledge financial support by “Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg” within the funding program Open Access Publishing.

Funding

We received financial support from the Ministry of Science, Research, and Art of Baden-Wuerttemberg. The funding source had no influence on the design of the study, analysis or interpretation of the data and also had no role in the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JHK and KH defined the scope of the project, developed the search strategy, wrote the manuscript, and had the final responsibility for the content of the manuscript. JHK, IM, and CB selected and extracted the literature. JHK and CB did the quality assessment. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Detailed search strategies for Pubmed and WoS CC. (DOCX 22 kb)

Additional file 2:

Quality score used to assess study quality. (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 3:

Detailed characteristics of all 81 studies included. (DOCX 690 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hilger-Kolb, J., Bosle, C., Motoc, I. et al. Associations between dietary factors and obesity-related biomarkers in healthy children and adolescents - a systematic review . Nutr J 16, 85 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-017-0300-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-017-0300-3