Abstract

Background

Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) is recommended for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in Africa. However, increasing SP resistance (SPR) affects the therapeutic efficacy of the SP. As molecular markers, Pfdhfr (dihydrofolate reductase) and Pfdhps (dihydropteroate synthase) genes are widely used for SPR surveillance. This study aimed to assess the prevalence of Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes mutations and haplotypes in Plasmodium falciparum isolates collected from Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea (EG).

Methods

In total, 180 samples were collected in 2013–2014. The single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes were identified with nested PCR and Sanger sequencing. The genotypes and linkage disequilibrium (LD) tests were also analysed.

Results

Sequences of Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes were obtained from 92.78% (167/180) and 87.78% (158/180) of the samples, respectively. For Pfdhfr, 97.60% (163/167), 87.43% (146/167) and 97.01% (162/167) of the samples carried N51I, C59R and S108N mutant alleles, respectively. The prevalence of the Pfdhps S436A, A437G, K540E, A581G, and A613S mutations were observed in 20.25% (32/158), 90.51% (143/158), 5.06% (8/158), 0.63% (1/158), and 3.16% (5/158) of the samples, respectively. In total, 3 unique haplotypes at the Pfdhfr locus and 8 haplotypes at the Pfdhps locus were identified. A triple mutation (CIRNI) in Pfdhfr was the most prevalent haplotype (86.83%), and a single mutant haplotype (SGKAA; 62.66%) was predominant in Pfdhps. A total of 130 isolates with 12 unique haplotypes were found in the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps combined haplotypes, 65.38% (85/130) of them carried quadruple allele combinations (CIRNI-SGKAA), whereas only one isolate (0.77%, 1/130) was found to carry the wild-type (CNCSI-SAKAA). For LD analysis, the Pfdhfr N51I was significantly associated with the Pfdhps A437G (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Bioko Island possesses a high prevalence of the Pfdhfr triple mutation (CIRNI) and Pfdhps single mutation (SGKAA), which will undermine the pharmaceutical effect of SP for malaria treatment strategies. To avoid an increase in SPR, continuous molecular monitoring and additional control efforts are urgently needed in Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria is a major global public health concern particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, with 219 million cases of malaria and approximately 435,000 deaths in 2017 [1]. Most of the severe clinical cases and deaths were caused by Plasmodium falciparum. Furthermore, pregnant women and children under 5 years old are the main victims of falciparum malaria. To alleviate the global malaria burden in a susceptible population, sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for use as intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women (IPTp) and infants (IPTi) in malaria-endemic regions [2].

Equatorial Guinea (EG) is a hyperendemic area of year-round malaria transmission [3], and the population is more frequently exposed to episodes of malaria [4]. Recent studies demonstrated P. falciparum parasites are the predominant species in EG, leading to approximately 291,700 cases in 2016; 15% of the deaths from this species were in children under 5 years old [5]. The authorities have deployed a series of measures that include effective anti-malarial drugs, vector control and case management for malaria control [6]. In 2004, The Bioko Island Malaria Control Project (BIMCP) was initiated on Bioko Island [7]. That project succeeded in reducing the infection rate, anaemia and child mortality [6]. Subsequently, similar measures have been adopted and were applied on mainland EG by the Equatorial Guinea Malaria Control Initiative (EGMCI) in 2007 [8]. In EG, SP has been used as a second-line treatment in cases of uncomplicated falciparum malaria for several decades. Furthermore, it was administered as the partner drug with artesunate as a first-line drug because of chloroquine treatment failure and as a malaria prophylaxis since 2004 [9], which may have led to P. falciparum isolates undergoing sustainable selection pressure. Soon afterwards, SP was replaced by artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) in response to widespread drug resistance in 2009, but it still remains the only choice for IPTp [10]. Of even greater concern, SP resistance (SPR) had already evolved in most African countries before SP was implemented as the recommended treatment. To ensure the prophylactic efficacy of this approach and support the national anti-malarial policy, large-scale screening and surveillance of SP drug resistance is highly recommended [11].

Targeting the P. falciparum enzymes dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), SP acts as a synergistic inhibitor of folate in the parasite [12, 13]. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that SPR is mainly conferred by amino acid point mutations at codons N51I, C59R, S108N, and I164L of Pfdhfr and S436A, A437G, K540E, A581G, and A613S of Pfdhps [14]. These hotspot mutations are suggested to be gradually displayed with the increase of SPR [15]. Many clinical failures have been reported after SP treatment was found in Africa [16,17,18]. Thus, an urgent need exists to continue monitoring and assessing resistance in P. falciparum populations when determining whether to administer this drug for prevention.

On Bioko Island, IPTp was introduced in 2004 [7, 9], and the Ministry of Health has implemented the use of two doses of SP during pregnancy and antenatal care, starting from the second trimester and 1 month apart [19]. An assessment of the prevalence of mutations in P. falciparum genes related to SPR on Bioko Island is needed to provide complementary information for this preventive strategy. In the current study, an assessment of the prevalence of the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps gene mutations and haplotypes was conducted on P. falciparum isolates collected from Bioko Island, EG.

Methods

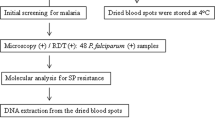

Study area and samples collection

The study was performed in 2013–2014 on Bioko Island, the Insular Region of EG, where malaria is endemic and has continuous transmission throughout the year. Venous blood (3 ml) was collected from P. falciparum-infected patients and confirmed by thick and thin smears stained with diluted Giemsa. Additionally, positive blood spots were air dried, individually reserved in coded plastic bags with silica desiccant beads, and kept at room temperature for further molecular assessment.

Ethics statement

The Ethics Committees of Malabo Regional Hospital on Bioko Island gave scientific and ethical permission (EGCNGD-071). Consent was obtained from all persons or their legal guardians before sample collection.

DNA extraction and PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from dried filtered bloodspots (DBS) by following the Chelex-100 extraction procedure described in the previous report [20]. The Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes were amplified by nested PCR, and the conditions for amplification were as previously described [21]. The mutations of the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes in the amplified nested PCR products were purified and detected subsequently by Sanger sequencing (Genewiz, Soochow, China). All sequences were analysed using DNAstar (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI, USA).

Data analysis

All data were analysed with SPSS 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The percentages of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and haplotypes were calculated with a 95% CI as described previously [22]. Differences in allele prevalence were compared using Pearson Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test, when conditions were appropriate. To determine the association between the SNPs of the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes, linkage disequilibrium (LD) tests were performed for each possible pair-wise SNP implicated as a drug-resistant marker in the two genes by calculating the D’ and r2 values using Haploview 4.2 software [23]. P values, less than 0.05 indicated significance.

Results

General information

In total, 180 isolates were evaluated. Then, 167 and 158 samples were successfully amplified, sequenced and genotyped for the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes, respectively. Of these successfully sequenced isolates, 130 sequences without any mixed types in Pfdhfr and Pfdhps were analysed for combined genotypes.

Prevalence of individual point mutations in Pfdhfr and Pfdhps

A high prevalence of Pfdhfr mutant alleles was detected in the analysed samples. The two major mutations, N51I (97.60%; 163/167) and S108N (97.01%; 162/167), showed similar prevalence, followed by C59R (87.43%; 146/167). The C59R mutant allele showed lower prevalence compared to N51I and S108N (χ2 = 6.141, P = 0.013; χ2 = 6.082, P = 0.014). No mutation was identified at positions 50 and 164. The key mutation of Pfdhps linked to sulfadoxine resistance at codon A437G was predominant at 90.51% (143/158), while the prevalence of the S436A mutation was found to be 20.25% (32/158), and the K540E, A581G and A613S mutations were less frequent, occurring at rates of 5.06% (8/158), 0.63% (1/158) and 3.16% (5/158), respectively. The A437G mutation occurred at a significantly different rate compared with S436A (χ2 = 153.837, P < 0.001), K540E (χ2 = 234.34, P < 0.001), A581G (χ2 = 259.538, P < 0.001), and A613S (χ2 = 249.161, P < 0.001). Similar to A437G, the S436A occurred at a significantly different rate compared with K540E (χ2 = 17.929, P < 0.001), A581G (χ2 = 34.142, P < 0.001) and A613S (χ2 = 24.726, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Prevalence of Pfdhfr and Pfdhps haplotypes

In the reconstitution of the haplotypes, 3 and 8 distinct genotypes were observed in Pfdhfr and Pfdhps, respectively, and mixed genotypes were also found in both genes. For Pfdhfr, only 1.2% (2/167) of the isolates were wild type CNCSI whereas 86.83% (145/167) carried the triple mutation CIRNI. The double mutant CICNI occurred with low prevalence at 5.99% (10/167). The overall prevalence of the mixed haplotypes was 5.99% (10/167) as follows: 0.6% (1/167) CNC/RSI, 4.19% (7/167) CIC/RNI, 0.6% (1/167) CIRS/NI, and 0.6% (1/167) CN/IC/RS/NI. For Pfdhps, the single mutated haplotype SGKAA was present in 62.66% (99/158) of the samples, followed by the double mutant haplotypes AGKAA in 10.76% (17/158), whereas only one isolate exhibited the triple mutated haplotype SGEGA. Of the remaining samples, 5.7% (9/158) harboured AAKAA, 4.43% (7/158) SGEAA, 0.63% (1/158) SGKAS, and 2.53% (4/158) AGKAS. The overall prevalence of mixed haplotypes was 11.39% (18/158) as follows: 0.63% (1/158) S/AAKAA, 3.8% (6/158) S/AGKAA, 1.9% (3/158) SGK/EAA, 0.63% (1/158) SGKA/GA, 1.27% (2/158) AGKA/GA, 0.63% (1/158) S/AGKA/GA, 1.9% (3/158) S/AA/GKAA, and 0.63% (1/158) SGK/EA/GA (Table 2).

Pfdhfr and Pfdhps allele combinations

When the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps haplotypes were combined, 12 genotypes were verified and are shown in Table 3. Quadruple mutant haplotypes with a triple Pfdhfr and a single Pfdhps mutation (CIRNI-SGKAA) was the most common at 65.38% (85/130). One sample at the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps loci was fully a wild type. The second prevalent haplotype was CIRNI-AGKAA with a frequency of 12.31% (16/130). The quintuple mutation (CIRNI-SGEAA) and sextuple mutation (CIRNI-SGEGA) were found in 4.62% (6/130) and 0.77% (1/130) of the isolates, respectively. The occurrence of other combined haplotypes was generally low: 0.77% (1/130) CNCSI-SGKAA, 4.62% (6/130) CICNI-SGKAA, 0.77% (1/130) CIRNI-SAKAA, 0.77% (1/130) CICNI-SGEAA, 5.38% (7/130) CIRNI-AAKAA, 0.77% (1/130) CIRNI-SGKAS, and 3.08% (4/130) CIRNI-AGKAS.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) test for Pfdhfr and Pfdhps haplotypes

The LD pattern for each SNP in the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes was assessed (Fig. 1). For the Pfdhfr gene, base substitution mutations of T152A, T175C and G323A were related to the single amino acid mutations of N51I, C59R, S108N, respectively. Similarly, the T1482G, C1486G, A1794G, and G2013T in the Pfdhps gene indicated mutations of S436A, A437G, K540E, and A613S, respectively.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between pairs of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located in Pfdhfr and Pfdhps and implicated in drug resistance for Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. For the Pfdhfr gene, base substitution mutations of T152A, T175C, and G323A are related to single amino acid mutations of N51I, C59R, and S108N, respectively. Similarly, the T1482G, C1486G, A1794G, and G2013T in the Pfdhps gene are related to mutations of S436A, A437G, K540E, and A613S, respectively. According to the four-gamete test, these SNPs are divided into two blocks (black frame). The number in the square indicates a D’ value. The square with dark red and light red indicates a linkage that was statistically significant (P < 0.05). The square with Cambridge blue indicates a linkage is present but is not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The square with white indicates no linkage is present

Several statistically significant associations were found among the SNPs located in both the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes (Fig. 1). For the Pfdhfr gene, T152A, T175C and G323 were in an LD block. The T152A (N51I) were significantly associated with the SNPs (T175C, C59R and G323A, S108N) with a D’ value of 0.84 (P < 0.05) and 1.0 (P < 0.05), respectively. Similarly, the T175C was significantly associated with the G323A (0.71, P < 0.05). For the Pfdhps gene, T1482G, C1486G, A1794G, and G2013T formed an LD block. The sole SNP (T1482G, S436A) were significantly associated with the SNPs (C1486G, A437G; A1794G, K540E; and G2013T, A613S) with D’ values of 0.75, 1.0 and 0.73, respectively. The SNP (T152A) of the Pfdhfr gene coding N51I was significantly associated with the C1486G, and the value is 0.68. No such association was detected in the other SNPs of either the Pfdhfr or Pfdhps genes.

Discussion

The rapid and widespread development of anti-malarial drug resistance is directly influencing and hindering the process of malaria control, prevention and elimination [24]. Surveillance with molecular markers has allowed the early detection of drug resistance susceptibility and may provide fundamental information for drug policy [25]. The current study displays the mutations and haplotypes of the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes from isolates collected from the general population on Bioko Island, thus allowing the degree of SPR in this malaria hotspot to be inferred.

The results demonstrate that Pfdhfr polymorphism associated with SPR persists at high frequency. A high prevalence of the Pfdhfr N51I mutation in 97.60% and the S108N mutation in 97.01% of the samples was found among the P. falciparum population on Bioko Island (Table 1), and these mutations also had been found at a very high level (97.9 and 99.1%, respectively) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in 2008 [26]. For C59R, the level was significantly lower than for N51I and S108N, similar to observations in the mainland of EG [4]. Like neighbouring countries, Pfdhfr I164L, which is related to high-grade SPR, has been reported at low proportions (1.4%) in rural areas of the EG mainland [4, 27]. Fortunately, this mutation was not found in any isolates within the study. Although the mutations of Pfdhfr C50R and I164L are not found in the present data, the high prevalence of three well-characterized mutations in Pfdhfr (N51I, C59R, S108N) indicate the P. falciparum isolates from Bioko island display high pyrimethamine resistance that needs to be addressed by the EGMCI. For the Pfdhfr haplotypes, 86.83% of the isolates carried the Pfdhfr triple mutation (CIRNI) (Table 2) and was reported in 80% of P. falciparum infections in 2005 from the mainland of EG, 100% in 2005 in Cameroon [28], and 72.4% in Gabon [29]. This triple mutation is an important SPR indicator, but its detrimental effects may be largely compromised by an absence of the Pfdhfr I164L mutation [30, 31]. The frequency of the Pfdhfr double mutant CICNI was 5.99% (Table 2), and this genotype has a lesser degree of resistance compared with the triple mutation CIRNI [29]. For the dominant mutant haplotype CIRNI (86.83%) and the double mutant haplotype CICNI (5.99%), the results are consistent with previous studies in EG and Central Africa [4, 10, 32, 33]. If the CIRNI haplotype is found concurrently with the Pfdhps mutations, it is associated with a high level of resistance [34]. The reported prevalence of the Pfdhfr triple mutation was also lower than those previously reported at the site where the proportion of the Pfdhfr triple mutation reached a frequency of 97%. Only 1.2% of the isolates (2/167) were a pure Pfdhfr wild type (CNCSI) (Table 2). The results indicate that almost all samples collected harbour pyrimethamine resistance.

Compared with the mutations of the Pfdhfr gene, the mutations of the Pfdhps gene exhibit a relatively low prevalence, except for the A437G mutation (90.51%, 143/158) (Table 1), which is also common in other EG regions and several African countries [27, 31, 35]. This mutation has been reported to occupy the key position of the initial mutation of sulfadoxine resistance, and its resistance increases along with the augmentation of other mutations in Pfdhps [36]. Although the prevalence of S436A is significantly lower than that of A437G, it is higher than for other mutations, including K540E, A581G and A613S. In Central Africa, the Pfdhps K540E mutation was less prevalent, which was also confirmed in this study (5.06%, 8/158) (Table 1). This mutation is more common in East Africa, particularly in Tanzania [37] and Uganda [17]. The WHO has recommended that IPT with SP should be abandoned in areas where the K540E mutation has been detected at > 95% and Pfdhps the A581G mutations are detected at > 10% because it could be ineffective [11]. Fortunately, only 5.06% (5/158) of the isolates showed the Pfdhps K540E mutation, and 0.63% (1/158) of the isolates harboured the A581G mutation in current survey (Table 1). The relatively low prevalence of these mutations suggests that IPT-SP can possibly be efficacious on Bioko Island, EG. The A613S mutations were detected in 3.16% (5/158) of the isolates, which is consistent with reports in Central African countries, including the DRC [27] and Cameroon [29]. For the Pfdhps haplotype, the single-mutant SGKAA haplotype predominates in our results (62.66%) (Table 2), similar to observations made in Gabon [38] and the DRC [39]. AGKAA is present in 10.76% of the isolates (Table 2), and an increased trend was detected in Gabon between 2013 and 2014 [38]. Parasites with double- and triple-mutant Pfdhps haplotypes were observed at a low frequency (Table 2), suggesting a low tendency in the emergence and development of the sulfadoxine resistance alleles.

The combination of the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps mutant alleles generated 12 different haplotypes in the present survey (Table 3). Only one wild-type haplotype (CNCSI-SAKAA) was found in this study (Table 3). The quadruple mutant (CIRNI-SGKAA) was predominant, with a prevalence of 65.38% (Table 3), which is higher than reports from mainland EG (54%) [4]. The saturation of the Pfdhfr triple mutants could further induce the Pfdhps mutants, and thus, the presence of quadruple mutants (CIRNI-SGKAA) was common [40]. Although quintuple mutant genotypes (CIRNI-SGEAA) are highly linked to SP failure [34], this mutant was detected at a rate of 4.62% (Table 3). WHO recommends surveillancefor this genotype and inhibition of IPTp-SP when the prevalence of this quintuple mutant exceeds 50% [31]. To date, this quintuple mutant is less than 10% in other areas of EG [4, 10]. Previous in vitro studies demonstrated that the quadruple mutant (CIRNI-SGKAA) has a less deleterious effect on SP-IPT than the quintuple mutant genotypes (CIRNI-SGEAA) [41]. Notably, the ‘super resistant’ alleles (CIRNI-SGEGA) may render SP ineffective [42], but these were detected in only one isolate. Although this occurrence is low, sustainable monitoring for SPR and avoiding the growth of super resistance alleles are still critical.

Although the LD analysis of the SNPs between the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes showed a strong linkage between N51I and A437G, those main SNPs of the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes form two independent LD blocks, respectively. These results indicate that the mutations located in the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes have relative independence. However, combined chemotherapy will likely lead to the occurrence and progress of resistance gene mutations even though the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes are located on different chromosomes [40]. For the Pfdhfr gene, T152A, T175C, and G323A develop as a block. When distributed in the Pfdhfr gene, these SNPs exhibit strong linkage, particularly of N51I and S108N (D’: 0.71–1, P < 0.05). For the Pfdhps gene, the T1482G, C1486G, A1794G, and G2013T were found in an LD block. Although the SNPs in Pfdhps gene show weak linkage and no significant differences (P > 0.05), strong linkages were also commonly detected from S436A and other mutations, including A437G, K540E and A613S. Notably, the study had weaknesses, including the small sample size and the lack of full-length DNA sequences for the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes. In the present study, a 594-bp fragment of the Pfdhfr and a 711-bp fragment of the Pfdhps gene were amplified, based on previous study [21]. The sequences from these two fragments provide only limited information for LD analysis. Thus, the complete nucleotide sequences from the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes and the microsatellite loci flanking these genes [43] need to be amplified and genotyped in further study. Genetic diversity information and differentiation data from microsatellite loci flanking the Pfdhfr and Pfdhps genes will demonstrate whether the P. falciparum isolates have ever undergone selection in response to SP and may provide valuable information to solve anti-malarial drug resistance, particularly SPR.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that this area had a high prevalence of the Pfdhfr triple mutation (CIRNI) and the Pfdhps single mutation (SGKAA), which could undermine the efficacy of SP for chemoprevention strategy. To avoid increases in SPR, continuous molecular monitoring and additional control efforts are urgently needed.

References

WHO. World Malaria Report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Gosling RD, Cairns ME, Chico RM, Chandramohan D. Intermittent preventive treatment against malaria: an update. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:589–606.

Benito A, Roche J, Molina R, Amela C, Alvar J. Application and evaluation of QBC malaria diagnosis in a holoendemic area. Appl Parasitol. 1994;35:266–72.

Berzosa P, Estebancantos A, García L, González V, Navarro M, Fernández T, et al. Profile of molecular mutations in pfdhfr, pfdhps, pfmdr1, and pfcrt genes of Plasmodium falciparum related to resistance to different anti-malarial drugs in the Bata District (Equatorial Guinea). Malar J. 2017;16:28.

Guerra M, de Sousa B, Ndong-Mabale N, Berzosa P, Arez AP. Malaria determining risk factors at the household level in two rural villages of mainland Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2018;17:203.

Kleinschmidt I, Sharp B, Benavente LE, Schwabe C, Torrez M, Kuklinski J, et al. Reduction in infection with Plasmodium falciparum one year after the introduction of malaria control interventions on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:972–8.

Kleinschmidt I, Torrez M, Schwabe C, Benavente L, Seocharan I, Jituboh D, et al. Factors influencing the effectiveness of malaria control in Bioko Island, equatorial Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:1027–32.

Ridl FC, Bass C, Torrez M, Govender D, Ramdeen V, Yellot L, et al. A pre-intervention study of malaria vector abundance in Rio Muni, Equatorial Guinea: their role in malaria transmission and the incidence of insecticide resistance alleles. Malar J. 2008;7:194.

Charle P, Berzosa P, Descalzo MA, Lucio AD, Raso J, Obono J, et al. Efficacy of artesunate + sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine (AS + SP) and amodiaquine + sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine (AQ + SP) for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Equatorial Guinea (Central Africa). J Trop Med. 2014;2009:781865.

Guerra M, Neres R, Salgueiro P, Mendes C, Ndongmabale N, Berzosa P, et al. Plasmodium falciparum genetic diversity in continental Equatorial Guinea before and after Introduction of artemisinin-based combination therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;61:e02556.

WHO. Policy brief for the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Triglia T, Wang P, Sims PF, Hyde JE, Cowman AF. Allelic exchange at the endogenous genomic locus in Plasmodium falciparum proves the role of dihydropteroate synthase in sulfadoxine-resistant malaria. EMBO J. 1998;17:3807–15.

Zolg JW, Plitt JR, Chen GX, Palmer S. Point mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene as the molecular basis for pyrimethamine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;36:253–62.

Felix KK, Damien B, Anna F, Michael N, Christevy V, Francine N. High prevalence of sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine resistance-associated mutations in Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from pregnant women in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;33:32–6.

Mita T, Ohashi J, Venkatesan M, Marma ASP, Nakamura M, Plowe CV, et al. Ordered accumulation of mutations conferring resistance to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:130–9.

Uchenna Anthony U, Obi SN, Onah HE, Ugwu EOV, Leonard Ogbonna A, Chioma Roseline U, et al. The impact of intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine on the prevalence of malaria parasitaemia in pregnancy. Trop Doct. 2012;42:133–5.

Braun V, Rempis E, Schnack A, Decker S, Rubaihayo J, Tumwesigye NM, et al. Lack of effect of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy and intense drug resistance in western Uganda. Malar J. 2015;14:372.

Desai M, Gutman J, Taylor SM, Wiegand RE, Khairallah C, Kayentao K, et al. Impact of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance on effectiveness of intermittent preventive therapy for malaria in pregnancy at clearing infections and preventing low birth weight. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;62:323–33.

Rehman AM, Mann AG, Schwabe C, Reddy MR, Roncon Gomes I, Slotman MA, et al. Five years of malaria control in the continental region, Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2013;12:154.

Li J, Chen J, Xie D, Montenguba S, Eyi JUM, Matesa RA, et al. High prevalence of pfmdr1 N86Y and Y184F mutations in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Bioko island, Equatorial Guinea. Pathog Glob Health. 2014;108:339.

Pearce RJ, Chris D, Daniel C, Frank M, Cally R. Molecular determination of point mutation haplotypes in the dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase of Plasmodium falciparum in three districts of northern Tanzania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1347–54.

Li J, Chen J, Xie D, Eyi UM, Matesa RA, Obono MMO, et al. Molecular mutation profile of Pfcrt and Pfmdr1 in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;36:552–6.

Patel P, Bharti PK, Bansal D, Ali NA, Raman RK, Mohapatra PK, et al. Prevalence of mutations linked to antimalarial resistance in Plasmodium falciparum from Chhattisgarh, Central India: a malaria elimination point of view. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16690.

Xu C, Wei Q, Yin K, Sun H, Li J, Xiao T, et al. Surveillance of Antimalarial Resistance Pfcrt, Pfmdr1, and Pfkelch13 Polymorphisms in African Plasmodium falciparum imported to Shandong Province, China. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12951.

Vestergaard LS, Ringwald P. Responding to the challenge of antimalarial drug resistance by routine monitoring to update national malaria treatment policies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77(6 Suppl):153–9.

Mobula L, Lilley B, Tshefu AK, Rosenthal PJ. Resistance-mediating polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum infections in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:555–8.

Nkoli Mandoko P, Rouvier F, Matendo Kakina L, Moke Mbongi D, Latour C, Losimba Likwela J, et al. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum parasites resistant to sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: emergence of highly resistant pfdhfr/pfdhps alleles. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:2704–15.

Menemedengue V, Sahnouni K, Basco L, Tahar R. Molecular epidemiology of malaria in Cameroon. XXX. sequence analysis of Plasmodium falciparum ATPase 6, dihydrofolate reductase, and dihydropteroate synthase resistance markers in clinical isolates from children treated with an artesunate-sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine combination. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:22–5.

Ngomo JMN, Mawilimboumba DP, M’Bondoukwe NP, Ella RNN, Akotet MKB. Increased prevalence of mutant allele Pfdhps 437G and Pfdhfr triple mutation in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from a rural area of Gabon, three years after the change of malaria treatment policy. Malar Res Treat. 2016;2016:1–6.

Rain AN, Azrina NN, Jenarun J, Hakim SL, Hasidah MS, Zakiah I, et al. High prevalence of mutation in the Plasmodium falciparum dhfr and dhps genes in field isolates from Sabah, Northern Borneo. Malar J. 2013;12:198.

Grais RF, Laminou IM, Woimesse L, Makarimi R, Bouriema SH, Langendorf C, et al. Molecular markers of resistance to amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine in an area with seasonal malaria chemoprevention in south central Niger. Malar J. 2018;17:98.

Mendes C, Salgueiro P, Gonzalez V, Berzosa P, Benito A, do Rosario VE, et al. Genetic diversity and signatures of selection of drug resistance in Plasmodium populations from both human and mosquito hosts in continental Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2013;12:114.

Chauvin P, Menard S, Iriart X, Nsango SE, Tchioffo MT, Abate L, et al. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum parasites resistant to sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine in pregnant women in Yaounde, Cameroon: emergence of highly resistant pfdhfr/pfdhps alleles. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2566–71.

Salem MS, Lekweiry KM, Bouchiba H, Pascual A, Pradines B, Boukhary AO, et al. Characterization of Plasmodium falciparum genes associated with drug resistance in Hodh Elgharbi, a malaria hotspot near Malian-Mauritanian border. Malar J. 2017;16:140.

Osarfo J, Tagbor H, Magnussen P, Alifrangis M. Molecular markers of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance in parasitemic pregnant women in the middle forest belt of Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:1714–7.

Wernsdorfer WH, Noedl H. Molecular markers for drug resistance in malaria: use in treatment, diagnosis and epidemiology. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:553–8.

Kavishe RA, Kaaya RD, Nag S, Krogsgaard C, Notland JG, Kavishe AA, et al. Molecular monitoring of Plasmodium falciparum super-resistance to sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine in Tanzania. Malar J. 2016;15:335.

Voumbo-Matoumona DF, Kouna LC, Madamet M, Maghendji-Nzondo S, Pradines B, Lekana-Douki JB. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum antimalarial drug resistance genes in Southeastern Gabon from 2011 to 2014. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:1329–38.

Baraka V, Delgadoratto C, Nag S, Ishengoma DS, Madebe RA, Mavoko HM, et al. Different origin and dispersal of sulphadoxine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum haplotypes between Eastern Africa and Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;49:456–64.

Zhang Y, Yan H, Wei G, Han S, Huang Y, Zhang Q, et al. Distinctive origin and spread route of pyrimethamine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Southern China. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 2014;58:237–46.

Kaingonadaniel EPS, Gomes LR, Gama BE, Almeidadeoliveira NK, Fortes F, Ménard D, et al. Low-grade sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from Lubango, Angola. Malar J. 2016;15:309.

Hemming-Schroeder E, Umukoro E, Lo E, Fung B, Tomás-Domingo P, Zhou G, et al. Impacts of antimalarial drugs on Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance markers, western Kenya, 2003–2015. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98:692–9.

Alam MT, de Souza DK, Vinayak S, Griffing SM, Poe AC, Duah NO, et al. Selective sweeps and genetic lineages of Plasmodium falciparum drug -resistant alleles in Ghana. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:220–7.

Authors’ contributions

JL conceived and designed the experiments. ML and JTC coordinated the field collections of patient isolates. JTC, JUME, RAM and MMOO carried out microscopic examination. YY and TTJ performed the experiments. JL, HXF, KW, WXD, and HBT analysed the data. JL and TTJ wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Chinese Medical Aid Team to the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, and to all participants who contributed their blood samples. The authors also thank Santiago-m Monte-Nguba for his technical help during the samples collection and diagnosis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Current study was approved by the ethics committees of Malabo Regional Hospital in Bioko Island. The informed consent was obtained from all participated individuals.

Funding

This study was supported by the Foundation for Innovative Research Team of Hubei University of Medicine (Grant Number FDFR201603) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 81802046).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, T., Chen, J., Fu, H. et al. High prevalence of Pfdhfr–Pfdhps quadruple mutations associated with sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Malar J 18, 101 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-2734-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-2734-x