Abstract

Background

Resistance to anti-malarial drugs hinders efforts on malaria elimination and eradication. Following the global spread of chloroquine-resistant parasites, the Republic of Congo adopted artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) in 2006 as a first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria. To assess the impacts after implementation of ACT, a molecular surveillance for anti-malarial drug resistance was conducted in Congo 4 and 9 years after the introduction of ACT.

Methods

Blood samples of 431 febrile children aged 1–10 years were utilized from two previous studies conducted in 2010 (N = 311) and 2015 (N = 120). All samples were screened for malaria parasites using nested PCR. Direct sequencing was used to determine the frequency distribution of genetic variants in the anti-malarial drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum genes (Pfcrt, Pfmdr1, Pfatp6, Pfk13) in malaria-positive isolates.

Results

One-hundred and nineteen (N = 70 from 2010 and N = 49 from 2015) samples were positive for P. falciparum. A relative decrease in the proportion of chloroquine-resistant haplotype (CVIET) from 100% in 2005, 1 year before the introduction and implementation of ACT in 2006, to 98% in 2010 to 71% in 2015 was observed. Regarding the multidrug transporter gene, a considerable reduction in the frequency of the mutations N86Y (from 73 to 27%) and D1246Y (from 22 to 0%) was observed. However, the prevalence of the Y184F mutation remained stable (49% in 2010 compared to 54% in 2015). Isolates carrying the Pfatp6 H243Y was 25% in 2010 and this frequency was reduced to null in 2015. None of the parasites harboured the Pfk13 mutations associated with prolonged artemisinin clearance in Southeast Asia. Nevertheless, 13 new Pfk13 variants are reported among the investigated isolates.

Conclusion

The implementation of ACT has led to the decline in prevalence of chloroquine-resistant parasites in the Republic of Congo. However, the constant prevalence of the PfMDR1 Y184F mutation, associated with lumefantrine susceptibility, indicate a selective drug pressure still exists. Taken together, this study could serve as the basis for epidemiological studies monitoring the distribution of molecular markers of artemisinin resistance in the Republic of Congo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the Republic of Congo, malaria remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Chloroquine and sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine were extensively used for several decades as first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria, but parasites rapidly developed resistance to both these drugs [1–5]. As a result, in 2006, Congo changed its national drug policy and switched to artesunate + amodiaquine (ASAQ) and artemether + lumefantrine (AL) combinations as first-line and second-line drugs, respectively, for the treatment of acute uncomplicated malaria.

Chloroquine resistance (CQR) is caused by mutations in two genes, Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (Pfcrt) and multidrug resistance transporter-1 (Pfmdr1), both located on the digestive food vacuole of the parasite [6]. These two genes also reduce the susceptibility to other quinolone anti-malarial agents such as amodiaquine, lumefantrine and mefloquine [7–9]. Many studies reported that in the absence of drug pressure, chloroquine-resistant strains have been replaced by sensitive ones [10, 11].

Many P. falciparum candidate genes are believed to be associated with artemisinin resistance. The endoplasmic and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase orthologue of P. falciparum (Pfatp6) has been postulated to be the target of artemisinin [12]. The H243Y, L263E, E431K, A623E, and S769N mutations have been shown to influence the functional activities in Pfatp6 [13–15]. In 2014, Ariey et al. showed that mutations (C580Y, R539T, Y493H, M476I) in the Pfk13 gene were associated with delayed parasite clearance [16]. As chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum strains spread worldwide from Southeast Asia, a similar devastating effect can also occur in case of artemisinin-resistant isolates. However, it has been shown that artemisinin-resistant parasites could also emerge independently in Southeast Asia, as Pfk13 mutations occur unexpectedly in many sites within the region [17].

Long-term monitoring of parasite sensitivity to previously withdrawn anti-malarial drugs, such as CQ, can provide useful surveillance information if these drugs target similar resistance markers to current or candidate ACT partner drugs [18]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of polymorphisms in the anti-malarial resistance genes, including Pfcrt, Pfmdr1, Pfatp6, and Pfk13 in field isolates from the Republic of Congo collected from two cross-sectional studies conducted in 2010 and 2015, approximately four and nine years after the adoption of ACT.

Methods

Study site and sample collection

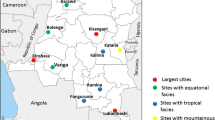

The study was conducted in the Southern and Northern districts in Brazzaville, the capital of the Republic of Congo. Malaria occurs holo-endemically and the transmission rates in the country are high and perennial, the majority of malaria cases being caused by P. falciparum. A total of 431 children aged 1–9 years were recruited in two phases: from April to June 2010 [Group A (N = 311)] and from September 2014 to February 2015 [Group B (N = 120)] from previous studies [19, 20] were utilized in this study. The 2010 cohort was from three districts of Makélékélé health division in southern region of Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. This cohort comprised of children aged 1–9 years and are permanent residents of the study area. The second cohort (September 2014 to February 2015) was collected from children aged from 1 to 10 years presenting with fever at the paediatric ward of the MNG hospital in Talangai, a northern Brazzaville region in Republic of Congo. This study was conducted in febrile children presenting with fever at the MNG hospital. Children who were positive for malaria by microscopy were included. Febrile children with other pathologies such as severe diarrhoea, pulmonary infection and HIV were excluded. At the time of enrolment 4 mL of whole blood were collected in heparinized tubes from all children and thick and thin blood smears were performed. In the case of malaria (positive thick and thin blood smears with axillary temperature ≥37.5 °C), collected blood samples were stored at −80 °C for molecular analyses, parasite density determined and children were treated with AS + AQ or AL. Ethical approval was given by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Research on Health Sciences of the Republic of Congo. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians of children.

Plasmodium species identification, and Pfcrt, Pfmdr1, Pfatp6, Pfk13 genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from 200 μL of peripheral whole blood samples using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The Plasmodium 18S rRNA gene was amplified by nested PCR to detect positive samples and further differentiate the species as described elsewhere [21, 22]. The primer pairs and thermocycling conditions are summarized in Table 1. Fragments of the Pfcrt (410 bp containing the polymorphisms at codons 72–76), Pfmdr1 [(580 bp including the polymorphisms at codons 86 and 184) and (864 bp containing the polymorphisms at codons 1034–1246)], Pfatp6 (800 bp carrying the polymorphisms at codons 243–769) and Pfk13 (849 bp comprising the main polymorphisms associated with delayed clearance in Southeast Asia) were amplified by nested PCR as described elsewhere [11, 23, 24]. The primer sequences and PCR conditions are described in Table 2. The PCR products were visualized through electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gel stained with SYBR Green I in 1× Tris-electrophoresis buffer (90 mM Tris–acetate, pH 8.0, 90 mM boric acid, 2.5 mM EDTA). Thereafter, PCR products were purified using Exo-SAP-IT (USB, Affymetrix, USA) and directly used as templates for DNA sequencing using the BigDye terminator v. 1.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) on an ABI 3130XL DNA sequencer. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified by assembling the sequences with each reference sequence using Codon code Aligner 4.0 software and were reconfirmed visually from their respective electropherograms.

Results

Plasmodium species identification

Using nested PCR for the species identification, 22.5% (70/311) and 40.8% (49/120) samples collected in 2010 and 2015, respectively, were positive for P. falciparum. The other species namely Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale were not detected in the study samples. The positive samples for P. falciparum malaria infection were screened for genetic variants in the Pfcrt, Pfmdr1, Pfatp6, and Pfk13 associated with anti-malarial drug resistance.

Pfcrt polymorphisms

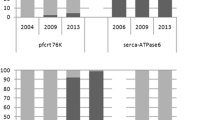

The success rate of Pfcrt amplicon sequencing was equally 57% with the samples from the 2010 cohort (40/70) and the 2015 cohort (28/49). The mutation frequencies are shown in Table 3. A triple mutation M74I, N75E and K76T was observed, each occurring at a frequency of 98% in 2010 and 71% in 2015. All the mutants carried the Cysteine–Valine–Isoleucine–Glutamate–Threonine (CVIET) haplotype while the wild type strains had the Cysteine–Valine–Methionine–Asparagine–Lysine (CVMNK) haplotype.

Pfmdr1 polymorphisms

Forty-one samples (59%) from 2010 and 26 samples (53%) from 2015 were sequenced for the detection of Pfmdr1 polymorphisms. The frequency of the Pfmdr1 gene mutations at positions 86 and 1246 are shown in Table 3. The frequency of N86Y mutant alleles was 73% in 2010 and 27% in 2015. The D1246Y mutation in 2010 occurred at a frequency of 22 and 0% in 2015. Neither the S1034C mutation nor the N1042D mutation in the Pfmdr1 gene was observed in the sequenced samples. The prevalence of the Y184F variant was 49% in 2010 and 54% in 2015. Other mutations occurred at quite low frequencies are represented in Table 3.

Pfatp6 polymorphisms

Eight samples (11%) from 2010 and 16 samples (33%) from 2015 were successfully sequenced to identify mutations in the Pfatp6 gene. Out of all the five key point mutations that were investigated, only H243Y and E431K mutations were observed. Both mutations occurred in 2010 at a frequency of 25% (2/8) and 12% (1/8), respectively, while in 2015, only the E431K mutation was observed occurring at a frequency of 12% (2/16). Other mutations found at positions 291 (I291V), 402 (L402V), 569 (N569K), 630 (A630S), 632 (G632E), 639 (G639D), 646 (F646F), and 747 (H747Y) are shown in Table 4. In addition to these SNPs, a variation of asparagine-tandem repeat region (codon 457–465) was observed in one sample from 2010, with an insertion of two asparagine residues after the 465th codon.

Pfk13 polymorphisms

Regarding the Kelch13 propeller domain, 41 out of 70 samples (59%) for 2010 cohort and 25 out of 49 samples (51%) for 2015 cohort were sequenced and used for analysis. The identified mutations in the Kelch13 propeller domain are shown in Table 4. The Pfk13 variants M476I, Y493H, R539T, I543T, and C580Y reported to occur in Southeast Asia were not observed in the Republic of Congo. Thirteen new substitutions were identified in the Pfk13 propeller domain. Six Pfk13 non-synonymous substitutions were observed in the propeller blades. The Pfk13 non-synonymous variants I552M and S549P observed in this study were previously reported in Central African Republic and in India, respectively.

Discussion

Malaria is still considered as one of the major health problems in the Republic of Congo and uncomplicated malaria occurs in young children due to P. falciparum. Malaria incidence is 0.9 malaria episode/year/child in Brazzaville and malaria transmission is perennial both in southern and northern Brazzaville, with P. falciparum being the most predominant species. In this study, P. falciparum was the only species detected in all the malaria-positive samples. Several factors, including both malaria parasite (e.g., pyrogenic threshold, multiplication rate, cytoadhesion) and host genetics (e.g., immunity, tolerance, pregnancy, co-morbidities) can influence the prevalence of the disease [25]. The wide spread of CQ-resistant parasites prompted the WHO to recommend ACT for the management of the disease in endemic regions. In 2006, Congo changed its national policy introducing ACT for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. The first report describing the prevalence of polymorphisms in Pfcrt conferring CQR showed that all the P. falciparum isolates were carrying the Pfcrt mutant alleles [2, 5]. The Pfcrt CVIET haplotype has been shown to be the most prevalent in Africa in contrast to the SVMNT haplotype found predominantly in Southeast Asia [23, 26]. Also, the occurrence of the Pfcrt M74I and N75E mutations has been linked to the K76T mutation as reported by Severini et al. who noted a 100% linkage between these alleles [27]. This explains the occurrence at the same frequency of these three mutations in this study. Studies conducted in Malawi and Tanzania reported a successful restoration of CQ-sensitive strains after the implementation of ACT for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria [28–30]. The return of these CQ-sensitive strains as observed in other studies support the hypothesis that the removal of drug pressure has led to a re-expansion of a heterogeneous susceptible parasites that might have prevailed when CQ was used.

Likewise, a significant decrease in the prevalence of the Pfcrt haplotypes associated with CQR was noted in this study from 2005 in republic of Congo [2], 1 year before the treatment policy was changed. However, their frequency did not decrease further after 9 years since the implementation of ACT, suggesting a possible use of CQ in the region by the population owing to the fact that it is less expensive than ACT.

Mutations in the Pfmdr1 and changes in its copy number have been associated with the development of decreased parasite sensitivity to several anti-malarial drugs. The major SNPs in the Pfmdr1 gene are N86Y, Y184F and D1246Y. The wild-type N86 has been shown to be responsible for the increased tolerance to drugs such as artemether [31] and 86Y associated with delayed parasite clearance with parenteral artesunate [32]. The mutant allele 86Y has been shown to associate with increased susceptibility to mefloquine in in vitro experiments [33]. Many studies that evaluated the influence of Pfmdr1 mutations in vitro have reported that, 184F or 1042N alleles decrease artemether and lumefantrine sensitivity in Thai isolates [34], Pfmdr1 86Y and Pfcrt76T in Kenyan isolates [35]. A yet another recent study from Burkina Faso reports on influence of Pfmdr1 86Y and Pfcrt76T mutations in AL and ASAQ treatment [36]. The N86Y and Y184F mutants are prevalent in Asian and African continents while S1034C, N1042F and D1246Y alleles are common in South American countries [37]. It is interesting to note that 86Y mutant allele prevalence is decreased in 2015 when compared to 2010 cohort samples. Pfmdr1 86Y and 1246Y alleles are linked to CQR in Africa and the 86Y allele is associated with decreased quinine sensitivity in African clinical isolates. The fact that Pfmdr1 gene mutations are not the principal actor in CQR [38, 39] might explain the decrease in the frequency of the Pfmdr1 mutations linked to CQR observed between 2010 and 2015. Both Pfmdr1 and Pfcrt genes are present on the membrane of the digestive vacuole in the malarial parasite and is believed to regulate the chemical solutes from the drug across the membrane. Few studies have reported that certain Pfmdr1 and Pfcrt alleles are in linkage and substantiated their functional relatedness [40, 41].

The occurrence of key mutations in the Pfatp6 gene linked to artemisinin resistance before the use of artemisinin and its derivatives in malaria treatment has been a major subject of controversy. The main question raised is whether these mutations occur as a result of some natural events or through prior exposure of parasites to drug pressure [14, 24]. One possible confounding factor could be the use of herbal plants in the treatment of malaria, which might have similar chemical constituents to artemisinin, and which is common practice in many malaria-endemic countries. Only the Pfatp6 H243Y and E431K mutations were identified among the five key mutations investigated. The variation in the asparagine-tandem repeat region had been previously reported by Tanabe et al. [42] but this had no role in artemisinin resistance. Despite the fact that none of the driving mutations for artemisinin resistance in the Pfk13 propeller domain reported by Ariey et al. [16] was identified, in the present study non-synonymous variants I552M and S549P are detected, which were previously reported in isolates from the Central African Republic and India, respectively.

Conclusions

The new and unreported mutations identified in this study could help in long-term surveillance of the development of artemisinin resistance in the Republic of Congo. This study on molecular surveillance will support to predict sensitivity to different anti-malarials used in Republic of Congo and will additionally provide information on fixation of any multidrug resistance alleles in this population. The results observed in this study could serve as the basis for epidemiological studies monitoring the distribution of molecular markers of anti-malarial drug resistance in the Republic of Congo.

Abbreviations

- Pfmdr1 :

-

Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance 1

- Pfatp6 :

-

Plasmodium falciparum Ca2+-ATPase

- Pfk13 :

-

Plasmodium falciparum Kelch-13 propeller domain

- ACT:

-

artemisinin-based combination therapies

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Mabiala-Babela J, Makoumbou P, Mbika-Cardorelle A, Tsiba J, Senga P. Evolution de la mortalité hospitalière chez l’enfant à Brazzaville (Congo). Med Afr Noire. 2009;56:5–8.

Mayengue PI, Ndounga M, Davy MM, Tandou N, Ntoumi F. In vivo chloroquine resistance and prevalence of the pfcrt codon 76 mutation in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the Republic of Congo. Acta Trop. 2005;95:219–25.

Ndounga M, Tahar R, Basco LK, Casimiro PN, Malonga DA, Ntoumi F. Therapeutic efficacy of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and the prevalence of molecular markers of resistance in under 5-year olds in Brazzaville, Congo. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1164–71.

Ndounga M, Casimiro PN, Miakassissa-Mpassi V, Loumouamou D, Ntoumi F, Basco LK. [Malaria in health centres in the southern districts of Brazzaville, Congo](in French). Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2008;101:329–35.

Nsimba B, Jafari-Guemouri S, Malonga DA, Mouata AM, Kiori J, Louya F, et al. Epidemiology of drug-resistant malaria in Republic of Congo: using molecular evidence for monitoring antimalarial drug resistance combined with assessment of antimalarial drug use. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:1030–7.

Babiker HA, Pringle SJ, Abdel-Muhsin A, Mackinnon M, Hunt P, Walliker D. High-level chloroquine resistance in Sudanese isolates of Plasmodium falciparum is associated with mutations in the chloroquine resistance transporter gene pfcrt and the multidrug resistance Gene pfmdr1. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1535–8.

Duraisingh MT, Jones P, Sambou I, von Seidlein L, Pinder M, Warhurst DC. The tyrosine-86 allele of the pfmdr1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum is associated with increased sensitivity to the anti-malarials mefloquine and artemisinin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;108:13–23.

Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, Bolaji OM, Sowunmi A, Kyle DE, et al. Association between mutations in Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter and P. falciparum multidrug resistance 1 genes and in vivo amodiaquine resistance in P. falciparum malaria-infected children in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:155–61.

Picot S, Olliaro P, de Monbrison F, Bienvenu AL, Price RN, Ringwald P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence for correlation between molecular markers of parasite resistance and treatment outcome in falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2009;8:89.

Bell DJ, Nyirongo SK, Mukaka M, Zijlstra EE, Plowe CV, Molyneux ME, et al. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine-based combinations for malaria: a randomised blinded trial to compare efficacy, safety and selection of resistance in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1578.

Mekonnen SK, Aseffa A, Berhe N, Teklehaymanot T, Clouse RM, Gebru T, et al. Return of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum parasites and emergence of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax in Ethiopia. Malar J. 2014;13:244.

Eckstein-Ludwig U, Webb RJ, Van Goethem ID, East JM, Lee AG, Kimura M, et al. Artemisinins target the SERCA of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2003;424:957–61.

Jambou R, Legrand E, Niang M, Khim N, Lim P, Volney B, et al. Resistance of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates to in vitro artemether and point mutations of the SERCA-type PfATPase6. Lancet. 2005;366:1960–3.

Menegon M, Sannella AR, Majori G, Severini C. Detection of novel point mutations in the Plasmodium falciparum ATPase6 candidate gene for resistance to artemisinins. Parasitol Int. 2008;57:233–5.

Valderramos SG, Scanfeld D, Uhlemann AC, Fidock DA, Krishna S. Investigations into the role of the Plasmodium falciparum SERCA (PfATP6) L263E mutation in artemisinin action and resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3842–52.

Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505:50–5.

Takala-Harrison S, Jacob CG, Arze C, Cummings MP, Silva JC, Dondorp AM, et al. Independent emergence of artemisinin resistance mutations among Plasmodium falciparum in Southeast Asia. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:670–9.

Plowe CV, Roper C, Barnwell JW, Happi CT, Joshi HH, Mbacham W, et al. World antimalarial resistance network (WARN) III: molecular markers for drug resistant malaria. Malar J. 2007;6:121.

Etoka-Beka MK, Ntoumi F, Kombo M, Deibert J, Poulain P, Vouvoungui C, et al. Plasmodium falciparum infection in febrile Congolese children: prevalence of clinical malaria 10 years after introduction of artemisinin-combination therapies. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21:1496–503.

Koukouikila-Koussounda F, Malonga V, Mayengue PI, Ndounga M, Vouvoungui CJ, Ntoumi F. Genetic polymorphism of merozoite surface protein 2 and prevalence of K76T pfcrt mutation in Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from Congolese children with asymptomatic infections. Malar J. 2012;11:105.

Fuehrer HP, Stadler MT, Buczolich K, Bloeschl I, Noedl H. Two techniques for simultaneous identification of Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri by use of the small-subunit rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:4100–2.

Snounou G, Singh B. Nested PCR analysis of Plasmodium parasites. Methods Mol Med. 2002;72:189–203.

Ariey F, Fandeur T, Durand R, Randrianarivelojosia M, Jambou R, Legrand E, et al. Invasion of Africa by a single pfcrt allele of South East Asian type. Malar J. 2006;5:34.

Zakeri S, Hemati S, Pirahmadi S, Afsharpad M, Raeisi A, Djadid ND. Molecular assessment of atpase6 mutations associated with artemisinin resistance among unexposed and exposed Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates to artemisinin-based combination therapy. Malar J. 2012;11:373.

Galatas B, Bassat Q, Mayor A. Malaria parasites in the asymptomatic: looking for the hay in the haystack. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:296–308.

Awasthi G, Satya Prasad GB, Das A. Pfcrt haplotypes and the evolutionary history of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107:129–34.

Severini C, Menegon M, Sannella AR, Paglia MG, Narciso P, Matteelli A, et al. Prevalence of pfcrt point mutations and level of chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Africa. Infect Genet Evol. 2006;6:262–8.

Alifrangis M, Lusingu JP, Mmbando B, Dalgaard MB, Vestergaard LS, Ishengoma D, et al. Five-year surveillance of molecular markers of Plasmodium falciparum antimalarial drug resistance in Korogwe District, Tanzania: accumulation of the 581G mutation in the P. falciparum dihydropteroate synthase gene. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:523–7.

Kublin JG, Cortese JF, Njunju EM, Mukadam RA, Wirima JJ, Kazembe PN, et al. Reemergence of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum malaria after cessation of chloroquine use in Malawi. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1870–5.

Malmberg M, Ngasala B, Ferreira PE, Larsson E, Jovel I, Hjalmarsson A, et al. Temporal trends of molecular markers associated with artemether-lumefantrine tolerance/resistance in Bagamoyo district, Tanzania. Malar J. 2013;12:103.

Lekana-Douki JB, Dinzouna Boutamba SD, Zatra R, Zang Edou SE, Ekomy H, Bisvigou U, et al. Increased prevalence of the Plasmodium falciparum Pfmdr1 86N genotype among field isolates from Franceville, Gabon after replacement of chloroquine by artemether–lumefantrine and artesunate–mefloquine. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:512–7.

Kremsner PG, Adegnika AA, Hounkpatin AB, Zinsou JF, Taylor TE, Chimalizeni Y, et al. Intramuscular artesunate for severe malaria in African Children: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001938.

Phompradit P, Wisedpanichkij R, Muhamad P, Chaijaroenkul W, Na-Bangchang K. Molecular analysis of pfatp6 and pfmdr1 polymorphisms and their association with in vitro sensitivity in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from the Thai–Myanmar border. Acta Trop. 2011;120:130–5.

Mungthin M, Khositnithikul R, Sitthichot N, Suwandittakul N, Wattanaveeradej V, Ward SA, et al. Association between the pfmdr1 gene and in vitro artemether and lumefantrine sensitivity in Thai isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:1005–9.

Mwai L, Kiara SM, Abdirahman A, Pole L, Rippert A, Diriye A, et al. In vitro activities of piperaquine, lumefantrine, and dihydroartemisinin in Kenyan Plasmodium falciparum isolates and polymorphisms in pfcrt and pfmdr1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5069–73.

Sondo P, Derra K, Diallo NS, Tarnagda Z, Kazienga A, Zampa O, et al. Artesunate-amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine therapies and selection of Pfcrt and Pfmdr1 alleles in Nanoro, Burkina Faso. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151565.

Veiga MI, Dhingra SK, Henrich PP, Straimer J, Gnadig N, Uhlemann AC, et al. Globally prevalent PfMDR1 mutations modulate Plasmodium falciparum susceptibility to artemisinin-based combination therapies. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11553.

Duraisingh MT, Cowman AF. Contribution of the pfmdr1 gene to antimalarial drug-resistance. Acta Trop. 2005;94:181–90.

Valderramos SG, Fidock DA. Transporters involved in resistance to antimalarial drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:594–601.

Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, Sowunmi A, Bolaji OM, Fateye BA, et al. Linkage disequilibrium between two distinct loci in chromosomes 5 and 7 of Plasmodium falciparum and in vivo chloroquine resistance in Southwest Nigeria. Parasitol Res. 2006;100:141–8.

Tumwebaze P, Tukwasibwe S, Taylor A, Conrad M, Ruhamyankaka E, Asua V et al. Changing antimalarial drug resistance patterns identified by surveillance at three sites in Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2016:jiw614.

Tanabe K, Zakeri S, Palacpac NM, Afsharpad M, Randrianarivelojosia M, Kaneko A, et al. Spontaneous mutations in the Plasmodium falciparum sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ -ATPase (PfATP6) gene among geographically widespread parasite populations unexposed to artemisinin-based combination therapies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:94–100.

Authors’ contributions

TPV and FN designed, supervised the experiments, performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. FFK, SJ, CNN, CNN, and KCK performed the experiments. MKEB contributed to the study design and sampling procedures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff and technicians of the pediatric ward of Marien Ngouabi Hospital in Brazzaville, and of the three districts of Makélékélé health division: Ngoko, Kinsana and Mbouono for their assistance in collecting the blood samples and clinical data of patients during the study. We express our gratitude to all the study participants involved in this study. We also acknowledge Velia Grummes for technical help during sequencing procedures.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are within the paper.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved to its final submission.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians of all participating children. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Research on Health Sciences of the Republic of Congo.

Funding

This work has been supported through the CANTAM project. CANTAM (Central Africa Network on Tuberculosis, HIV/AIDs and Malaria) is a network of excellence supported by EDCTP.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Koukouikila-Koussounda, F., Jeyaraj, S., Nguetse, C.N. et al. Molecular surveillance of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance in the Republic of Congo: four and nine years after the introduction of artemisinin-based combination therapy. Malar J 16, 155 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1816-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1816-x