Abstract

Background

Guidelines have classified patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and diabetes as a special population, with specific sections presented for the management of these patients considering their extremely high risk. However, in China up-to-date information is lacking regarding the burden of diabetes in patients with ACS and the potential impact of diabetes status on the in-hospital outcomes of these patients. This study aims to provide updated estimation for the burden of diabetes in patients with ACS in China and to evaluate whether diabetes is still associated with excess risks of early mortality and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) for ACS patients.

Methods

The Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China-ACS Project was a collaborative study of the American Heart Association and the Chinese Society of Cardiology. A total of 63,450 inpatients with a definitive diagnosis of ACS were included. Prevalence of diabetes was evaluated in the overall study population and subgroups. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to examine the association between diabetes and in-hospital outcomes, and a propensity-score-matched analysis was further conducted.

Results

Among these ACS patients, 23,880 (37.6%) had diabetes/possible diabetes. Both STEMI and NSTE-ACS patients had a high prevalence of diabetes/possible diabetes (36.8% versus 39.0%). The prevalence of diabetes/possible diabetes was higher in women (45.0% versus 35.2%, p < 0.001). Even in patients younger than 45 years, 26.9% had diabetes/possible diabetes. While receiving comparable treatments for ACS, diabetes/possible diabetes was associated with a twofold higher risk of all-cause death (adjusted odds ratio 2.04 [95% confidence interval 1.78–2.33]) and a 1.5-fold higher risk of MACCE (adjusted odds ratio 1.54 [95% confidence interval 1.39–1.72]).

Conclusions

Diabetes was highly prevalent in patients with ACS in China. Considerable excess risks for early mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events were found in these patients.

Trial registration NCT02306616. Registered December 3, 2014

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patients with both clinical cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes were classified as extreme-risk groups in recently published guidelines issued by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology [1]. The latest guidelines for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) also classified patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and diabetes as a special population and presented specific sections for the management of these patients in consideration of their extremely high risk [2,3,4,5]. However, limited studies have been conducted to evaluate the burden of diabetes on ACS patients in China in recent years. The latest studies to focus on the prevalence of diabetes were conducted more than 10 years ago [6, 7]. With the rapid increase in the prevalence of diabetes among the general population in China, the burden of diabetes among Chinese ACS patients needs to be re-evaluated. In addition, despite the advancements in the clinical management and the wide application of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the past decade, whether the excess risk caused by diabetes is reduced among ACS has remained unclear. Therefore, an up-to-date evaluation regarding the prevalence of diabetes in ACS patients in China and the potential impact of diabetes status on the outcomes of these patients during hospitalization is needed.

In this study, we aim to provide an updated estimation of the burden of diabetes in patients with ACS and to evaluate whether diabetes is still associated with excess risks for in-hospital all-cause death or major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) to these patients in China, based on the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China-ACS Project (CCC-ACS Project), a large nationwide registry and quality improvement study.

Research design and methods

Study design and population

The CCC-ACS project, a nationwide registry and quality improvement study with an ongoing database focusing on quality of ACS care, was launched in 2014 as a collaborative initiative of the American Heart Association and the Chinese Society of Cardiology. In Phases I and II of the project, only the tertiary hospitals were included, 150 centers representing the diversity of care for ACS in tertiary hospitals across China. Since July 2017, Phase III of the project has extended into secondary hospitals. The data for this study are based on Phases I and II of the project. Details of the design and methodology of the CCC project have been published [8]. A standard web-based data collection platform (Oracle Clinical Remote Data Capture, Oracle) was used in this study. Trained data abstractors in the participating hospitals reported the required data, which they abstracted from the patients’ original medical records. Eligible patients were consecutively reported to the CCC-ACS database for each month before the middle of the following month. Third-party clinical research associates performed quality audits to ensure that cases were reported consecutively rather than selectively. In addition, about 5% of reported cases were randomly selected, and the reported information was compared with the original medical records as a quality assessment and a method to promote accuracy and completeness of the reported data. According to the quality audit reports, the data in this study were appropriately reported with an accuracy rate greater than 95%.

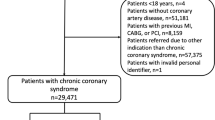

Based on principal discharge diagnosis, 63,641 inpatients with ACS were registered between November 2014 and June 2017 from 150 hospitals. Of these, 63,450 inpatients were included in this study after excluding 191 (0.3%) patients with incomplete demographic information. The flow chart for study population recruitment can be found in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Definition of diabetes

Diabetes was defined according to one of the following criteria: (1) a self-reported diabetes which was previously diagnosed by physicians or use of glucose-lowering drugs before hospitalization; (2) diabetes listed in the medical records as the secondary discharge diagnosis; (3) glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) concentration ≥ 6.5%.

Possible diabetes was defined in ACS patients with level of fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥ 7.0 mmol/L but without measurement of HbA1c, as we could not distinguish between undiagnosed diabetes and stress hyperglycemia in this group of patients by the results of FBG alone.

Definition of in-hospital outcomes

The outcomes of this study included all-cause deaths and MACCEs that occurred during hospitalization. MACCEs were defined as a combination of cardiac death, recurrent myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, and stroke. All of these outcomes were diagnosed by doctors during patients’ hospitalization and recorded in medical records.

Definition of other variables

Hypertension was defined as having a history of hypertension, receiving antihypertensive therapy, or systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg at admission. Elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was defined as serum LDL-C ≥ 1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL). Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) was defined as serum HDL-C < 1.0 mmol/L (40 mg/dL). Elevated triglyceride (TG) was defined as serum TG ≥ 2.3 mmol/L (200 mg/dL). Current smoking was defined as smoking in the preceding 1 year according to the medical records of the patients. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by the equation developed by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration [9]. A history of coronary heart disease (CHD) was specified if the patients had a clinical history of myocardial infarction or underwent PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) before the current hospitalization. Other clinical history of diseases, including cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, peripheral artery disease (PAD), atrial fibrillation, and renal failure was defined according to the notes on original medical records. Heart failure, cardiac arrest, and cardiac shock occurring within 24 h of the current admission were defined as a severe clinical condition. The definition of fivefold elevated myocardial injury markers was elevation of cardiac injury marker beyond fivefold the upper reference limit [5]. In addition, we evaluated the risk of in-hospital death using the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score whereby patients with a score greater than 140 were classified as high risk [10]. Subtypes of ACS were defined based on the principal discharge diagnosis of medical records. Patients with a diagnosis of non-STEMI and unstable angina were classified as NSTE-ACS. Cardiologists diagnosed patients based on guidelines of STEMI and NSTE-ACS issued by the Chinese Society of Cardiology [11, 12]. The diagnostic criteria included symptoms of chest pain, results of ECG, and biomarkers of myocardial injury.

Statistical analysis

As most of the patients with possible diabetes could be undiagnosed or were at high risk of developing diabetes, and needed the same care as diabetic patients during hospitalization [2,3,4,5, 13], for the purposes of this study we combined diabetes and possible diabetes for analysis. Prevalence of diabetes/possible diabetes and its 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated in the overall study population and in subgroups by sex, age groups, and CHD history. The characteristics, in-hospital treatments, and in-hospital outcomes of these patients were described and compared according to diabetic status in ACS patients. Continuous variables with normal distribution were shown as mean (standard deviation [SD]) and differences between groups were compared using t-tests; continuous variables with skewed distribution were shown as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test; and categorical variables were presented as the number (percentage) and compared using chi-square test. Logistic multivariable regression analysis was carried out to examine the association between diabetes/possible diabetes and in-hospital outcomes. Univariate analysis was performed first, followed by multivariate-adjusted analysis. The candidate adjusted factors are confounding factors that either have been included in the risk assessment or have been reported more than once with an effect on death or MACCE, including baseline characteristics, risk factors, medical history, clinical conditions at admission, and treatment during hospitalization, i.e., age (continuous), sex (male/female), current smoking (yes/no), SBP levels (continuous), heart rate (continuous), cardiac arrest at admission (yes/no), Killip class at admission (class I/II–III/IV), history of CHD (yes/no), cerebrovascular disease (yes/no), PAD (yes/no), heart failure (yes/no), renal failure (yes/no), eGFR (continuous), administration of dual antiplatelet therapy (yes/no), anticoagulant therapy (yes/no), statins (yes/no), β-blockers (yes/no), and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs)/angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) (yes/no) during hospitalization, PCI treatment (yes/no), fivefold elevated myocardial injury markers (yes/no), type of ACS (STEMI/NSTE-ACS), and whether patients were transferred from another hospital before the current hospitalization (yes/no). After forward stepwise selection with entry and exit criteria both set at the p = 0.15 level, the variables listed in the legend of Table 4 were eventually included in the multivariable adjusted logistic model of all-cause death and MACCE, respectively. Given the differences in pathologies, management, and prognosis of STEMI and NSTE-ACS, we performed the above analyses in these two subtypes of ACS patients.

Since some ACS patients with FBG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L but with HbA1c < 6.5% were classified as patients without diabetes, who could mostly be diagnosed with stress hyperglycemia and associated with increased risk of death and MACCE, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding these patients and recalculated the risk of diabetes/possible diabetes.

Subgroup analysis, including age, sex, Killip class, eGFR, GRACE score, PCI treatment, types of ACS, and whether the patient was transferred before the current hospitalization, was performed by using important characteristics in a multivariable adjusted logistic regression model. Odds ratios (ORs) between subgroups were compared using a Z-test [14].

In addition, we conducted a propensity-score-matched analysis to further confirm the association between diabetes/possible diabetes and in-hospital outcomes. First, a propensity score of having diabetes/possible diabetes was calculated by a logistic regression model with the variables age, sex, SBP levels, heart rate, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, eGFR, Killip class at admission, history of myocardial infarction, PCI, CABG, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, PAD, atrial fibrillation, renal failure, and type of ACS. Patients with and without diabetes/possible diabetes were then matched at a 1:1 ratio by propensity score using nearest-neighbor matching without replacement, with a caliper of 0.02. The absolute standardized differences of variables included for the calculation of propensity score were compared before and after propensity-score matching. Standardized differences < 10.0% for these included variables indicated a relatively small imbalance. The baseline characteristics and in-hospital management between the two propensity-score-matched subsets were re-compared. As some characteristics did not exactly match between the two groups even after the propensity-score matching, multivariable logistic regression was further performed to compare the risk by adjusting factors eventually included in the whole study population by stepwise selection.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Stata 14.0 (Stata, College Station, TX, USA). Two-tailed p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Prevalence of diabetes in ACS patients

The average age of the 63,450 ACS patients, 25.1% of whom were female, was 62.9 (± 12.4) years. Among these patients, a total of 23,880 (37.6%) had diabetes/possible diabetes (Table 1), including 29.7% diabetes and 7.9% possible diabetes. Both STEMI and NSTE-ACS patients had a high prevalence of diabetes/possible diabetes, but prevalence was slightly higher in patients with NSTE-ACS than in those with STEMI (39.0% versus 36.8%). Women had a higher proportion of diabetes/possible diabetes than men (45.0% versus 35.2%). The prevalence of diabetes/possible diabetes increased significantly with age. However, even in patients younger than 45 years, 26.9% of them had diabetes/possible diabetes. Patients with a history of CHD had a higher prevalence of diabetes/possible diabetes than those without CHD history (45.9% versus 36.6%).

Characteristics of ACS patients with diabetes

Compared with ACS patients without diabetes, patients with diabetes/possible diabetes had a higher frequency of previous diseases and major cardiovascular risk factors (Table 2). Of these ACS patients with diabetes/possible diabetes, 21.5% had previously diagnosed CVD and 51.2% had three or more other cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, different types of dyslipidemia, and smoking.

ACS patients with diabetes/possible diabetes also had more severe clinical conditions than those without diabetes at admission, with a higher frequency of heart failure (11.9% versus 7.2%), cardiac shock (3.7% versus 2.7%), and cardiac arrest (2.2% versus 1.8%). In addition, the proportion of high-risk patients based on GRACE scores was also significantly higher in patients with diabetes/possible diabetes in comparison with non-diabetic patients (39.2% versus 31.2%). Similar results were observed in subtypes of ACS patients with and without diabetes/possible diabetes.

In-hospital management of ACS patients with diabetes

We compared the treatments for ACS between patients with and without diabetes/possible diabetes with regard to STEMI and NSTE-ACS (Table 3). Most of the received treatments, including PCI, antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulant therapy, statins, and β-blockers, were comparable between patients with and without diabetes/possible diabetes. We did not observe a higher rate of CABG in ACS patients with diabetes in this study.

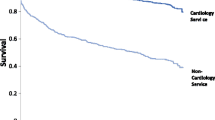

In-hospital outcomes of ACS patients with diabetes

The in-hospital outcomes were compared between ACS patients with and without diabetes/possible diabetes (Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Higher rates of all-cause death and MACCE were observed in all ACS patients with diabetes/possible diabetes as well as in the subtypes of ACS. In univariate logistic regression analysis, a significantly higher risk of all-cause death and MACCE was observed in patients with diabetes/possible diabetes (Table 4). The independent association was further evaluated using multivariable analyses (Table 4 and Additional file 1: Tables S2 and S3). After multivariable adjustment, diabetes/possible diabetes was associated with a twofold increased risk of all-cause death (OR, 2.04 [95% CI 1.78–2.33]) and a 1.5-fold increased risk of MACCE (OR, 1.54 [95% CI 1.39–1.72]).

In-hospital outcomes of ACS patients with and without diabetes. a In-hospital all-cause death of the whole study population. b In-hospital all-cause death of the propensity-score-matched population. c In-hospital MACCE of the whole study population. d In-hospital MACCE of the propensity-score-matched population. MACCE major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

We then conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the risk of diabetes/possible diabetes. After excluding patients with possible stress hyperglycemia (n = 2465) in patients without diabetes, diabetes/possible diabetes was still associated with an increased risk of in-hospital all-cause death (OR, 2.22 [95% CI 1.92–2.56]) and MACCE (OR, 1.63 [95% CI 1.46–1.83]).

Subgroup analyses were performed based on important baseline characteristics. Diabetes/possible diabetes was associated with increased risk of all-cause death and MACCE in all subgroups (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis for the association between diabetes/possible diabetes and in-hospital outcomes. a Association between diabetes/possible diabetes and all-cause death during hospitalization. b Association between diabetes/possible diabetes and MACCE during hospitalization. OR odds ratio, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, GRACE Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, ACS acute coronary syndrome, STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, NSTE-ACS non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome, MACCE major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

In addition, we conducted a propensity-score-matched analysis to further confirm the association between diabetes/possible diabetes and in-hospital outcomes. After propensity-score matching, 19,315 ACS patients with diabetes/possible diabetes were matched with 19,315 patients without diabetes (patients with possible stress hyperglycemia were excluded before matching). After matching, the standardized differences were less than 10.0% for all variables included for the calculation of propensity score, indicating that ACS patients with and without diabetes/possible diabetes were well matched (Additional file 1: Figure S2). The characteristics and in-hospital treatment between these two groups were re-compared, whereby most of the characteristics were comparable (Additional file 1: Table S4). The rates of all-cause death and MACCE remained higher in patients with diabetes/possible diabetes, and an excess risk of in-hospital outcomes independently associated with diabetes/possible diabetes was also found (all-cause death: OR, 2.21 [95% CI 1.83–2.66]; MACCE: OR, 1.58 [95% CI 1.38–1.82]) (Fig. 1 and Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we provided an updated estimation of the burden of diabetes in ACS patients in China and evaluated whether diabetes was independently associated with excess risks for in-hospital all-cause death and MACCE to these patients, based on a nationally representative registry study with a large sample.

Heavy burden of diabetes among ACS patients

We found that 1 in 3 male ACS patients and 2 in 5 female ACS patients had diabetes/possible diabetes. With the rapid increase in prevalence of diabetes in China, the proportion of diabetes in the ACS patients will continue to rise [15]. The China Heart Study published in 2006 reported that 37.4% of patients with acute coronary artery disease were diagnosed with diabetes by medical history and FBG [7], and 17.4% of these patients were further diagnosed with diabetes by oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). In this situation, the prevalence of diabetes in ACS patients may be higher than the current prevalence reported herein, as some patients with diabetes may not have been identified because OGTT currently is not applied in the routine clinical workup to assess the diabetic status of patients. These findings indicate that cardiologists in China have to manage a large proportion of ACS patients with diabetes in their clinical care.

However, there remains some doubt about whether our cardiologists are fully prepared to manage this group of patients. In this study, we found that 68.2% of patients (with both measurement of FBG and HbA1c) with FBG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L could be diagnosed with diabetes by HbA1c, which meant that about 70% of patients with possible diabetes could be diagnosed with diabetes with HbA1c tests; however, 57.0% patients did not receive a test for HbA1c during hospitalization. Therefore, for a considerable number of patients the best opportunity to identify and treat their previously undiagnosed diabetes might have been missed, particularly for those patients with little or no routine health care before the occurrence of ACS events. Effectively identifying these patients during hospitalization is thus the first key step in cardiologists’ management strategy. In addition, diabetes also has a great impact on the prognosis of various diseases, and long-term monitoring is necessary [16,17,18].

Worse in-hospital outcomes of ACS patients with diabetes

Our study showed that ACS patients with diabetes/possible diabetes had a substantially high risk for in-hospital outcomes compared with patients without diabetes, namely a twofold increased risk of all-cause death and a 1.5-fold increased risk of MACCE. A recently published systematic review and meta-analysis provided a summarized excess risk of early mortality from diabetes status in patients with myocardial infarction/ACS based on 86 studies published from 1970 to 2011 [19]. Here it was reported that diabetes was associated with a 1.7-fold higher risk of early mortality and that the relative risk of early death associated with diabetes did not change over time [19]. Compared with previous studies in Chinese ACS patients, the rates of all-cause death and MACCE during hospitalization have been significantly decreased in our study [20,21,22]. These findings might suggest that the advancements in the management of ACS patients during the last decades have improved the prognosis of ACS patients but have not led to a reduction of the risk gap between diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

However, one point worth noting is that most of the previous studies did not address the problem of undiagnosed diabetes and stress hyperglycemia [23, 24], which has been defined as possible diabetes in our study. Researchers compared patients with history (previously diagnosed) of diabetes and those without history of diabetes, which included all patients without diabetes, with undiagnosed diabetes, or with stress hyperglycemia. These analyses may underestimate the relative risks of diabetes given the increased risk of the reference group. In our study, we classified patients with undiagnosed diabetes and stress hyperglycemia (FBG ≥ 7 mmol/L) as possible diabetes as they did not have an HbA1c result, and who were associated with a threefold increased risk of all-cause death compared with those without diabetes. Therefore, all ACS patients with FBG ≥ 7 mmol/L or with diabetes should raise major concern in clinical practice in light of their extremely high risk. Relative hyperglycemia, a new concept, reported to associated with complications following an acute myocardial infarction [25], also need to be concerned.

The reasons for the excess risk of all-cause death and MACCE in ACS patients with diabetes/possible diabetes could be partially be explained [26,27,28], but some reasons are unexplained based on current analysis as the information on anti-diabetic treatment was not available to our study. In our study, we observed that the in-hospital management for ACS was similar between patients with and without diabetes. However, anti-diabetic therapy in the acute phase is also very important for the prognosis of ACS patients with diabetes, and inappropriate hypoglycemic treatment could significantly increase the risk of death [29]. The guidelines have given clear anti-diabetic drug recommendations for patients with both CVD and diabetes [30, 31], and an increasing number of studies have found that newer types of anti-diabetic drugs have a beneficial effect on lowering both blood glucose levels and risks of CVD, but conflicting results still exist [32,33,34,35,36]. In addition, the combined use of anti-diabetic drugs on cardiovascular events should also be concerned [37]. Future studies should take this information into consideration.

Whether in the American, European, or other countries of the world, ACS patients with diabetes is common (usually greater than one-third of patients) and associated with a higher risk of death and other adverse events [2,3,4,5, 38]. Although studies have reported that the cardiovascular outcomes of diabetes have been improved in recent years, number of people with diabetes still rises, the absolute burden of CVD will still be high [39]. Effective strategies to better manage the risk of these ACS patients with diabetes and improve their prognosis has always been the focus but also a challenge for cardiologists worldwide. In 2013, the European Society of Cardiology in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes developed the second guideline for diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, which calls for physicians in the fields of cardiovascular medicine and diabetes to join forces to research and manage these conditions, given the close relationship between CVD and diabetes [30]. In 2015, the Chinese Society of Cardiology in collaboration with other societies also issued a guideline on the management of abnormal glucose metabolism and CVD [40]. Following the efforts of both cardiologists and diabetologists, the risk of adverse events for ACS patients with diabetes/possible diabetes is expected to decrease [41].

Limitations

Some limitations of this study are worthy of mention. First, the results of OGTT during hospitalization were unavailable to this study, thus some diabetic patients may have been missed. However, OGTT was not routinely used in clinical practice, which future studies should take into consideration. Second, some patients with only increased FBG could not be definitively diagnosed with diabetes. However, using only tests for FBG revealed that at present, cardiologists do not pay sufficient attention to the diagnosis of diabetes in ACS patients. Finally, as this was a real-world study for ACS patients based on medical records, limited information regarding diabetes was gathered, including incomplete data on body mass index as well as uncollected data on physical exercise information, diabetes types, and in-hospital anti-diabetic therapy. Some other interest points regarding diabetes, such as gender differences, different revascularization strategies, and regional impacts, still need more research in the future [42,43,44].

Conclusions

Our results showed that diabetes was highly prevalent among ACS patients in China. Considerable excess risk for early mortality and MACCE was found in ACS patients with diabetes. These findings highlight the importance of early detection and appropriate management of diabetes in ACS patients, using specific therapies that have been demonstrated to improve outcomes.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease

- STEMI:

-

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- NSTE-ACS:

-

non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

- ACS:

-

acute coronary syndrome

- MACCE:

-

major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

- HbA1c:

-

glycated hemoglobin A1c

- FBG:

-

fasting blood glucose

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- LDL-C:

-

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TG:

-

triglyceride

- eGFR:

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- CHD:

-

coronary heart disease

- PCI:

-

percutaneous coronary intervention

- CABG:

-

coronary artery bypass grafting

- PAD:

-

peripheral artery disease

- GRACE:

-

Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- ACEIs:

-

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARBs:

-

angiotensin-receptor blockers

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- OGTT:

-

oral glucose tolerance test

- DAPT:

-

dual antiplatelet therapy

- UFH:

-

unfractionated heparin

- LMWH:

-

low molecular weight heparin

References

Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, Bloomgarden ZT, Fonseca VA, Garber AJ, Grunberger G, Guerin CK, Bell DSH, Mechanick JI, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(Supplement 2):1–87.

American College of Emergency P, Society for Cardiovascular A, Interventions, O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78–140.

Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR Jr, Jaffe AS, Jneid H, Kelly RF, Kontos MC, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-st-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139–228.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with st-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119–77.

Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267–315.

Liu J, Zhao D, Liu Q, Wang W, Sun J-Y, Wang M, Suo M. Study on the prevalence of diabetes mellitus among acute coronary syndrome inpatients in a multiprovincial study in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2008;29(6):526–9.

Hu DY, Pan CY, Yu JM for the China Heart Survey Group. The relationship between coronary artery disease and abnormal glucose regulation in China: the China Heart Survey. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(21):2573–9.

Hao Y, Liu J, Liu J, Smith SC Jr, Huo Y, Fonarow GC, Ma C, Ge J, Taubert KA, Morgan L, et al. Rationale and design of the improving care for cardiovascular disease in China (CCC) project: a national effort to prompt quality enhancement for acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2016;179:107–15.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YP, Castro AF, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12.

Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O, Pieper KS, Eagle KA, Cannon CP, Van De Werf F, Avezum A, Goodman SG, Flather MD, et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(19):2345–53.

Chinese Society of Cardiology, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. CSC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Chin J Cardiol. 2017;5:18.

Chinese Society of Cardiology, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. CSC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Chin J Cardiol. 2015;5:14.

Ali Abdelhamid Y, Kar P, Finnis ME, Phillips LK, Plummer MP, Shaw JE, Horowitz M, Deane AM. Stress hyperglycaemia in critically ill patients and the subsequent risk of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):301.

Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics notes—interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. Br Med J. 2003;326(7382):219.

Chan JCN, Zhang Y, Ning G. Diabetes in China: a societal solution for a personal challenge. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(12):969–79.

Luo M, Lim WY, Tan CS, Ning Y, Chia KS, van Dam RM, Tang WE, Tan NC, Chen R, Tai ES, et al. Longitudinal trends in HbA1c and associations with comorbidity and all-cause mortality in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;133:69–77.

Valent F, Tonutti L, Grimaldi F. Does diabetes mellitus comorbidity affect in-hospital mortality and length of stay? Analysis of administrative data in an Italian Academic Hospital. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54(12):1081–90.

Issa M, Alqahtani F, Ziada KM, Stanazai Q, Aljohani S, Berzingi C, Giordano J, Alkhouli M. Incidence and outcomes of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in patients hospitalized with decompensated diabetes. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(8):1297–302.

Bauters C, Lemesle G, de Groote P, Lamblin N. A systematic review and meta-regression of temporal trends in the excess mortality associated with diabetes mellitus after myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2016;217:109–21.

Tian L, Wei C, Zhu J, Liu L, Liang Y, Li J, Yang Y. Newly diagnosed and previously known diabetes mellitus and short-term outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2013;24(8):669–75.

Li J, Li X, Wang Q, Hu S, Wang Y, Masoudi FA, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM, Jiang L, China PCG. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in China from 2001 to 2011 (the China PEACE-Retrospective Acute Myocardial Infarction Study): a retrospective analysis of hospital data. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):441–51.

Yu LT, Tan HQ, Zhu J, Zhang Y, Li JD, Liu LS. Clinical characteristics, treatments and outcome of diabetic patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes in China. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2011;39(5):390.

Donahoe SM, Stewart GC, McCabe CH, Mohanavelu S, Murphy SA, Cannon CP, Antman EM. Diabetes and mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2007;298(7):765–75.

Franklin K, Goldberg RJ, Spencer F, Klein W, Budaj A, Brieger D, Marre M, Steg PG, Gowda N, Gore JM, et al. Implications of diabetes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(13):1457–63.

Lee TF, Burt MG, Heilbronn LK, Mangoni AA, Wong VW, McLean M, Cheung NW. Relative hyperglycemia is associated with complications following an acute myocardial infarction: a post hoc analysis of HI-5 data. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):157.

Savonitto S, Morici N, Nozza A, Cosentino F, Perrone Filardi P, Murena E, Morocutti G, Ferri M, Cavallini C, Eijkemans MJ, et al. Predictors of mortality in hospital survivors with type 2 diabetes mellitus and acute coronary syndromes. Diabetes Vasc Dis Res. 2018;15(1):14–23.

She J, Deng Y, Wu Y, Xia Y, Li H, Liang X, Shi R, Yuan Z. Hemoglobin A1c is associated with severity of coronary artery stenosis but not with long term clinical outcomes in diabetic and nondiabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):97.

Dai D, Chang Y, Chen Y, Yu S, Guo X, Sun Y. Gender-specific association of decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate and left vertical geometry in the general population from rural Northeast China. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):24.

Deedwania P, Kosiborod M, Barrett E, Ceriello A, Isley W, Mazzone T, Raskin P. Hyperglycemia and acute coronary syndrome: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Diabetes Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2008;117(12):1610–9.

Authors/Task Force M, Ryden L, Grant PJ, Anker SD, Berne C, Cosentino F, Danchin N, Deaton C, Escaned J, Hammes HP, et al. ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: the task force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J. 2013;34(39):3035–87.

Hong TP, Mu YM, Ji LN, Guo XH, Zhu DL, Tong NW, Huo Y, Shen YP, Zhao D, Jiao K, et al. Chinese expert consensus on anti-diabetic agents in treating patients with type 2 diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Chin J Diabetes. 2017;25(6):481–92.

Wang MT, Lin SC, Tang PL, Hung WT, Cheng CC, Yang JS, Chang HT, Liu CP, Mar GY, Huang WC. The impact of DPP-4 inhibitors on long-term survival among diabetic patients after first acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):89.

Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117–28.

Tsutsumi Y, Tsujimoto Y, Ikenoue T. Lixisenatide in type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1094–5.

Zhang Z, Chen X, Lu P, Zhang J, Xu Y, He W, Li M, Zhang S, Jia J, Shao S, et al. Incretin-based agents in type 2 diabetic patients at cardiovascular risk: compare the effect of GLP-1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors on cardiovascular and pancreatic outcomes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):31.

Li YR, Tsai SS, Chen DY, Chen ST, Sun JH, Chang HY, Liou MJ, Chen TH. Linagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes after acute coronary syndrome or acute ischemic stroke. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):2.

Chan CW, Yu CL, Lin JC, Hsieh YC, Lin CC, Hung CY, Li CH, Liao YC, Lo CP, Huang JL, et al. Glitazones and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors as the second-line oral anti-diabetic agents added to metformin reduce cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes patients: a nationwide cohort observational study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):20.

de Miguel-Yanes JM, Jimenez-Garcia R, Hernandez-Barrera V, Mendez-Bailon M, de Miguel-Diez J, Lopez-de-Andres A. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on in-hospital-mortality after major cardiovascular events in Spain (2002–2014). Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):126.

Jung CH, Chung JO, Han K, Ko SH, Ko KS, Park JY, Taskforce Team of Diabetes Fact Sheet of the Korean Diabetes A. Improved trends in cardiovascular complications among subjects with type 2 diabetes in Korea: a nationwide study (2006–2013). Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):1.

Chinese Society of Cardiology. The abnormal glucose metabolism and clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease diagnosis and treatment guidelines. Chin J Cardiol. 2015;43(6):488–506.

Bailey CJ, Tahrani AA, Barnett AH. Future glucose-lowering drugs for type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(4):350–9.

Ramanathan K, Abel JG, Park JE, Fung A, Mathew V, Taylor CM, Mancini GBJ, Gao M, Ding L, Verma S, et al. Surgical versus percutaneous coronary revascularization in patients with diabetes and acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(24):2995–3006.

Laverty AA, Bottle A, Kim SH, Visani B, Majeed A, Millett C, Vamos EP. Gender differences in hospital admissions for major cardiovascular events and procedures in people with and without diabetes in England: a nationwide study 2004–2014. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):100.

Shvartsur R, Shiyovich A, Gilutz H, Azab AN, Plakht Y. Short and long-term prognosis following acute myocardial infarction according to the country of origin. Soroka acute myocardial infarction II (SAMI II) project. Int J Cardiol. 2018;259:227–33.

Authors’ contributions

SS, YH, GF, JG, KT, CSM, YLH, and DZ designed the study; MGZ, YCH, NY, YYX and JL cleaned the data; MGZ analyzed the data; MGZ and DZ wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of all investigators in participating hospitals to the project (Additional file 1: Table S5).

Competing interests

Dr. Gregg C. Fonarow reports consulting for Bayer, Janssen, and Novartis. The authors declare that they have no competing interests in relation to this work.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of intellectual property rights, but are available from the corresponding author (Prof. Dong Zhao) on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board approval was granted for this research by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University. No informed consent was required.

Funding

The Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China (CCC)-ACS project is a collaborative study of the American Heart Association and Chinese Society of Cardiology. The American Heart Association was funded by Pfizer for the quality improvement initiative through an independent grant for learning and change.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

In-hospital outcomes of ACS patients with diabetes/possible diabetes. Table S2. The association between diabetes/possible diabetes and in-hospital all-cause death. Table S3. The association between diabetes/possible diabetes and in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Table S4. Characteristics of ACS patients with and without diabetes/ possible diabetes after propensity-score matching. Table S5. Investigators of CCC-ACS project. Figure S1. Flow chart for study population recruitment. Figure S2. Absolute standard differences before and after propensity score matching.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, M., Liu, J., Hao, Y. et al. Prevalence and in-hospital outcomes of diabetes among patients with acute coronary syndrome in China: findings from the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China-Acute Coronary Syndrome Project. Cardiovasc Diabetol 17, 147 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0793-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0793-x