Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) correlates with accelerated aging and earlier appearance of geriatric phenotypes, including frailty. However, whether pre-frailty or frailty predicts greater healthcare utilization in diabetes patients is unclear.

Methods

From the Longitudinal Cohort of Diabetes Patients in Taiwan (n = 840,000) between 2004 and 2010, we identified 560,795 patients with incident type 2 DM, categorized into patients without frailty, or with 1, 2 (pre-frail) and ≥ 3 frailty components, based on FRAIL scale (Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, and body weight Loss). We examined their long-term mortality, cardiovascular risk, all-cause hospitalization, and intensive care unit (ICU) admission.

Results

Among all participants (56.4 ± 13.8 year-old, 46.1% female, and 84.8% community-dwelling), 77.8% (n = 436,521), 19.2% (n = 107,757), 2.7% (n = 15,101), and 0.3% (n = 1416) patients did not have or had 1, 2 (pre-frail), and ≥ 3 frailty components (frail), respectively, with Fatigue and Illness being the most common components. After 3.14 years of follow-up, 7.8% patients died, whereas 36.6% and 9.1% experienced hospitalization and ICU stay, respectively. Cox proportional hazard modeling discovered that patients with 1, 2 (pre-frail), and ≥ 3 frailty components (frail) had an increased risk of mortality (for 1, 2, and ≥ 3 components, hazard ratio [HR] 1.05, 1.13, and 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–1.07, 1.08–1.17, and 1.15–1.36, respectively), cardiovascular events (HR 1.05, 1.15, and 1.13; 95% CI 1.02–1.07, 1.1–1.2, and 1.01–1.25, respectively), hospitalization (HR 1.06, 1.16, and 1.25; 95% CI 1.05–1.07, 1.14–1.19, and 1.18–1.33, respectively), and ICU admission (HR 1.05, 1.13, and 1.17; 95% CI 1.03–1.07, 1.08–1.14, and 1.06–1.28, respectively) compared to non-frail ones. Approximately 6–7% risk elevation in mortality and healthcare utilization was noted for every frailty component increase.

Conclusion

Pre-frailty and frailty increased the risk of mortality and cardiovascular events, and entailed greater healthcare utilization in patients with type 2 DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Frailty, an emerging public health concern worldwide, is characterized by an age-related accumulation of health deficits accompanied with an increased susceptibility to exogenous and endogenous insults [1, 2]. Whether defined by the deficit-accumulation approach or the physical frailty approach, the presence of frailty correlates with functional impairment and adverse health outcomes, providing the background for subsequent disability, hospitalization, nursing home stay, and loss of independence [3, 4]. Current studies suggest that frailty is not synonymous with multimorbidity and contributes independently to impaired outcomes in old adults [4]. In addition, a transitory status termed “pre-frailty” has been proposed to mark the early and potentially reversible condition prior to full-fledged frailty; pre-frailty is reportedly associated with a significantly higher risk of cardiovascular diseases, prolonged hospital stay, and impaired quality of life in affected elderly [5, 6]. Researchers have proposed that the identification of pre-frailty can facilitate earlier and more aggressive intervention to contain the detrimental influences of ensuing frailty, disability, and possibly mortality [7]. In light of these results, understanding the effect of frailty and especially pre-frailty, on the overall health and patients’ healthcare utilization assumes great importance for the care of old patients.

The global burden of diabetes mellitus (DM) rises with ageing, and is accompanied by a high mortality among affected individuals [8]. In Taiwan, a nationwide survey found that the overall incidence of DM rose from 0.76 to 0.93% within 10 years, equivalent to a 25% increase, and there were 1.22 million Taiwanese affected by DM in 2009. This was accompanied by an 80% increase in the total diabetic population and 55% increase in the prevalence rate during the sampling period [9]. Patients aged 60 or higher accounted for the majority (30–50%) of the diabetic population, and the proportion of male outnumbered that of female after 2005 [9]. On the other hand, the annual incidence of type 1 DM remained stable, with an increased risk among female children of older age [10].

Frailty is recognized as an influential complication for patients with DM, irrespective of age. In a large group of middle-aged adults, Chode et al. found that individuals with diabetes had a higher likelihood of being frail than those without diabetes, and the presence of frailty in DM patients conferred an even greater risk of functional impairment and deteriorated performance [11]. Another group also revealed that frailty in middle-aged to older diabetes adults predisposed these patients to limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) compared to non-frail ones [12]. The pathogenic linkage between DM and frailty potentially includes premature senescence of organ systems in a hyperglycemic status, chronic inflammation, increased oxidative stress, advanced glycation end-product accumulation, and insulin resistance, although a conclusive list is still under active pursuit [13, 14]. Nonetheless, previous data have already established the prognostic importance of frailty in patients with diabetes [15], while only a few studies have addressed the significance of pre-frailty. Furthermore, most studies focused on the adverse health outcomes of frailty including overall survival and functional outcomes, but the issue of healthcare utilization is under-recognized, especially among patients with diabetes. We hypothesized that both pre-frailty and frailty increased healthcare utilization in addition to mortality in patients with type 2 DM. We aimed to examine whether diabetic patients with pre-frailty or frailty consumed more healthcare resources than those without, using a national administrative database from Taiwan, an area with universal health coverage and a suitable substrate for analysis.

Methods

Ethical approval

The institutional review board of National Taiwan University Hospital (No. 201802063W) approved the current study; the study protocol adheres to the declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived due to data anonymity.

Participant enrollment and data sources

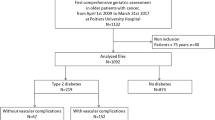

We harnessed the Longitudinal Cohort of Diabetes Patients database (LHDB), a population-based data source compiled by the National Health Research Institute of Taiwan, between 2004 and 2010, for participant recruitment. The database consists of an annual random sampling of 120,000 patients with an incident DM diagnosis from all areas of Taiwan, with their clinical records retrospectively traced up to 1999 and followed until 2014 [16], constituting a longitudinal cohort for epidemiologic analysis. The diagnosis of DM was established based on the presence of at least two times of out-patient International Classification of Disease-9-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 250.xx within 1 year, at least one time of DM diagnosis accompanied by prescriptions of any oral anti-diabetic agents (OADs), or at least one diagnosis during admission. Prior studies have affirmed of the validity and the utility of this diabetes cohort for analyzing short- and long-term outcome predictors and the quality of care among DM patients [16, 17]. We further narrowed down the diagnostic criteria by increasing the times of diagnosis required to at least three, and excluded pediatric patients (≤ 20 years), patients with type 1 DM, prevalent DM patients, and patients with premature mortality after developing type 2 DM (Fig. 1). The date when patients satisfied the criteria for DM diagnosis (the last out-patient clinic with a DM diagnosis) was designated as the index date. The severity of DM was evaluated using adjusted diabetic complication severity index (aDCSI) [18,19,20]. In brief, aDCSI is a modified version of DCSI and gauges the severity of DM based on the number of diabetic complications without laboratory finding criteria. Results from aDCSI exhibit good correlation with the original DCSI ones, and higher aDCSI scores are associated with a greater number of hospitalizations among DM patients during follow-up [18].

Exposures and primary outcomes

The primary exposure variable in this study was the presence and the severity of frailty. There are two approaches for assessing frailty in the existing literature, frail index and frail phenotype, both of which exhibit close associations with adverse outcomes in diverse populations [1, 2]. Evaluation of frailty severity was performed with the FRAIL scale, a highly cited and well-validated instrument consisting of five components (Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, and Loss of weight) [21,22,23]. We chose the FRAIL scale since its applicability in DM patients has been affirmed in the literature [11, 24]. However, the FRAIL scale is often assessed in research context but rarely during clinical encounter, rendering large-scale frailty screening based on FRAIL scale difficult [25]. Consequently, we attempted to operationalize frailty using FRAIL scale through the formulation of different diagnostic groupings.

Each frailty component was assessed based on the presence of selective diagnoses during at least two outpatient clinics or one hospitalization outlined in Table 1, within the preceding 5 years of the index date. Because the claim database did not contain measured clinical data (laboratory data), or results from in-person interviews or physical examinations, we selected diagnoses based on keyword search and relevant literature review [26, 27], followed by an in-depth review of expert geriatricians and epidemiologists, with consensus reached after two rounds of discussions. Diagnostic codes with close proximity or as surrogates to the underlying nature of the frailty components were included in the list (Table 1). The “Fatigue” component was identified using diagnoses containing the keywords “malaise” or “asthenia”. The ICD-9-CM code 780.7x (malaise and fatigue) has been shown to effectively capture patient complaint by others and in domestic studies [28, 29]. We additionally include 300.5 (neurasthenia), 797 (senile asthenia), and 780.99 (general weakness) to increase the detection efficiency and avoid under-reporting.

For “Resistance”, patients need to have difficulty stair climbing, and in this study, we identified “Resistance” based on the presence of “debility” or “fall”. Stair negotiation limitation is an important surrogate for functional decline and debility, while prior studies established that the code 799.3 could identify those with physical deconditioning [28, 30] and a tendency for fall. A history of fall correlates closely with gait imbalance and difficulty in stair climbing [31]. In light of these, we believe that the selected code groups can identify those with difficulty in stair climbing. “Ambulation” was recognized based on “walking difficulty” or “gait abnormality”. The diagnostic codes 719.7 (difficulty in walking) and 781.2 (gait abnormality) have been utilized to identify those with ambulation difficulty in large claim databases [28]. “Illness” was coded using the presence of at least four morbidities out of totally 10 within the lists (Table 1). The diagnostic code combinations for identifying each chronic illness have been validated by others in the literature and also in the database we used [32,33,34]. “Loss of weight” was identified using codes associated with “malnutrition”, “feeding difficulty”, “cachexia”, or “muscle wasting”, an approach validated in the past [32]. We defined pre-frailty as the presence of 1 or 2 components described above, and frailty as the presence of more than 2 components [21, 35].

The primary outcome of our study was the use of healthcare resources, including the incidence of hospitalization or intensive care unit (ICU) stay during follow-up. Secondary outcomes included the overall mortality and incident cardiovascular events during follow-up. Cardiovascular events examined in this study included incident myocardial infarction, unstable angina, heart failure, new-inset stroke (ischemic, hemorrhagic, or transient ischemic attack), and submission to revascularization procedures (coronary artery bypass graft/percutaneous coronary intervention) [36]. For patients with cardiovascular events, hospitalization or ICU admission, only the first episode of the event was included in our analysis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical variables were compared using independent t-tests and Chi square tests, respectively, while comparisons of more than two groups were performed with ANOVA. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA), and two-tail P-values lower than 0.05 were considered significant.

We first examined the distribution of each frailty component in the entire diabetes cohort, followed by categorization of patients with type 2 diabetes based on their frail component counts (0, 1, 2, ≥ 3) or the presence or absence of pre-frailty or frailty. We compared the demographic profiles, comorbidity statuses, DM severity, selected co-existing medications with influences on the survival and functional status, and OAD types between patients without and with different severities of frailty. We followed these patients until the end of this study or until 12/31/2010, and constructed Kaplan–Meier survival and event-free curves with between-group comparisons with a log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard modeling with mortality, cardiovascular events, hospitalization, and ICU admission as dependent variables was conducted, incorporating demographic (age, gender) and comorbidity profiles (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, malignancy, gout, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, obesity, and mental illnesses), experiences of hypoglycemia, substance use history (smoking and alcohol abuse), aDCSI, and co-existing medications (aspirin, β-blocker, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, clopidogrel, statin, fibrate, allopurinol, warfarin, benzodiazepine, anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, and all OADs identified) in full models. We also constructed Cox proportional hazard-based survival curves based on frailty component counts. Finally, we evaluated the contribution of each frailty component to the outcomes of interest individually, based on Cox regression modeling. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to examine the validity of our findings.

Results

Between 2004 and 2010, 840,000 patients with incident diabetes were identified; after using stricter criteria for DM diagnosis and excluding prevalent diabetes patients and pediatric and type 1 DM patients, 560,795 incident type 2 DM patients were finally enrolled for further analysis (Fig. 1). Among these patients, the mean age was 56.4 ± 13.8 years, with 46.1% female and 84.8% being community-dwelling. 77.8% (n = 436,521), 19.2% (n = 107,757), 2.7% (n = 15,101), and 0.3% (n = 1416) did not have or had 1, 2, and ≥ 3 frailty components, respectively, yielding a prevalence of pre-frailty and frailty at 21.9% and 0.3%, respectively. Among participants with diabetes with pre-frailty or frailty, Fatigue was the most common component qualified (60–95%), followed by Illness (30–95%) and Body weight loss (3–55%) (Table 2). Ambulation was the least common qualified component.

Severity of frailty was positively correlated with age, severity of diabetes and the incidence of most comorbidities except hyperlipidemia (Table 3). People with higher severity of frailty were more likely to receive medications that potentially affect their overall and cardiovascular survival, except statin and fibrate (Table 3). In contrast, those with higher frailty severity, possibly due to their increased risk of hypoglycemia, were less likely to receive multiple OADs including biguanides, sulfonylurea, α-glucosidase inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (Table 3).

After a mean 3.14 years of follow-up, mortality rate was 7.8%, and cardiovascular event rate was 8.1%. In addition, 36.6% and 9.1% of patients had an episode of hospitalization and ICU admission, respectively. Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrated that pre-frail and frail diabetes participants showed significantly higher mortality, cardiovascular risk, and healthcare utilization (hospitalization and ICU admission) than non-frail individuals (Fig. 2; P < 0.001 for comparisons between all four groups for all endpoints). Cox proportional hazard modeling revealed that compared to non-frail diabetes participants, diabetes participants with 1, 2, or ≥ 3 frailty components had gradually higher overall mortality (for 1, 2, and ≥ 3 components, hazard ratio [HR] 1.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–1.07; HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.08–1.17; and HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15–1.36, respectively) after adjusting for demographic profiles, comorbidities, diabetes severity, and medications (Table 4). For every 1-component increase, 6% higher mortality was noted (HR 1.06; 95% CI 1.04–1.08). Similarly, compared to those without frailty, diabetes participants with 1, 2, or ≥ 3 frailty components had higher risk of developing cardiovascular events (for 1, 2, and ≥ 3 components, HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.02–1.07; HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.1–1.2; and HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.01–1.25, respectively), with a 6% higher cardiovascular risk per component increase (HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.04–1.08). Frail diabetes participants also used significantly more healthcare resources, assessed as higher likelihood of hospitalization (for 1, 2, and ≥ 3 components, HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.05–1.07; HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.14–1.19; and HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.18–1.33, respectively) and ICU admission (for 1, 2, and ≥ 3 components, HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.07; HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.08–1.14; and HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.06–1.28, respectively), than non-frail ones (Table 4). Cox proportional hazard-based survival and event-free curves for overall survival, cardiovascular events, hospitalization, and ICU admission dictated essentially dictated similar findings (Fig. 3).

We further analyzed the primary and secondary endpoints based on the presence of each frailty component per se, instead of frailty component counts. After adjusting for demographic profiles, all comorbidities, aDCSI, all the medications including outcome-modifying medications and OADs, and other frailty components, we found that Fatigue (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1–1.06), Resistance (HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.13–1.3), and Body weight loss (HR 1.37, 95% CI 1.3–1.44) were independently associated with higher mortality (Table 5). For cardiovascular events, resistance (HR 1.09, 95% CI 1–1.17), illness (HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.14–1.21), and body weight loss (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.07–1.23) exhibited risk association. For healthcare utilization, the presence of each of the five components was associated with a significantly higher risk of hospitalization, while impairment in Resistance (HR 1.2, 95% CI 1.12–1.28) and Body weight loss (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.25–1.4) were associated with a higher risk of ICU admission (Table 5).

Finally, we performed sensitivity analyses by accounting for additional comorbidities and lifestyle factors, varying the length during which frailty components were ascertained (Fig. 4), and including those with type 1 DM (Table 4). After adjusting for mental illnesses history, obesity, hypoglycaemia history, and substance use history, we showed that frail diabetes participants with 1, 2, or ≥ 3 frailty components still had higher overall mortality (for 1, 2, and ≥ 3 components, HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.02–1.07; HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.09–1.18; and HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15–1.36, respectively) than non-frail ones (Table 4). Similarly, frail diabetes participants with 1, 2, or ≥ 3 frailty components had significantly higher risk of developing cardiovascular events (for 1, 2, and ≥ 3 components, HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.08; HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.1–1.2; and HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.02–1.25, respectively) than non-frail ones. Frail diabetes participants consumed significantly more healthcare resources, assessed as higher likelihood of hospitalization (for 1, 2, and ≥ 3 components, HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.05–1.07; HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.13–1.19; and HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.17–1.33, respectively) and ICU admission (for 1, 2, and ≥ 3 components, HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.02–1.07; HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.08–1.17; and HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.06–1.27, respectively), than non-frail ones (Table 4). In addition, we used stricter criteria to identify frailty in these diabetes participants through narrowing the time frame of frailty definition from 5 to 1 or 3 years. Pre-frail and frail patients were still associated with a significantly higher risk of mortality, developing cardiovascular events, and utilization of more healthcare resources, compared to non-frail individuals, even after varying the time frame of frailty definition to 1 or 3 years (Additional file 1: Table S1). Finally, the inclusion of type 1 DM patients in our analysis did not alter our findings (Table 4).

Discussion

In the current study, we estimated the prevalence of pre-frailty and frailty in a nationally representative sample of diabetes patients, based on a widely used FRAIL scale applicable to populations with various diseases. We discovered that patients with pre-frailty and frailty had a significantly higher healthcare utilization and an increased risk of adverse overall and cardiovascular outcome than non-frail individuals; furthermore, this risk increase was correlated with frailty severity independent of other interfering factors, with a 6–7% increase per frailty component. In light of the importance of frailty and also pre-frailty, we propose that early management targeting the entire spectrum of frailty may have the potential to reduce healthcare spending, and thus to benefit public health, in addition to its known effect on patient survival.

Identifying frailty using large claim datasets has become an attractive approach recently [27], because patients with frailty are often under-represented in most clinical studies and claim datasets possess the advantage of large case numbers with a higher probability of balanced clinical features. Using data from Medicare beneficiaries ≥ 65 years old, Kim et al. created a claims-based frailty index approximating a survey-based one, and their results exhibited similar to even better predictive efficacy for adverse health outcomes [37]. A similar approach has been attempted by others using the deficit accumulation approach based on diagnoses groups, with good outcome discrimination ability [38]. On the other hand, Segal et al. implemented Fried’s frail phenotype based on Medicare claims from the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort; similarly, their results were predictive of patient mortality and the risk of nursing home admission [26]. In this study, we adopted a method similar to that of Segal et al. albeit with modifications, including the matching of each included diagnosis to the FRAIL scale (fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illnesses, and weight loss), the exclusion of demographic and socioeconomic variables to mimic the physical frail phenotype directly, and the removal of codes with indirect relationship to the FRAIL construct. Because the results from our approach exhibited excellent predictive efficacy for adverse outcomes (Table 4), we believe that the groups of patients being identified likely have physical frailty with impaired prognosis.

In this study, we found that “Fatigue” was the predominant frailty component in type 2 diabetes patients with pre-frailty and frailty, followed by “Illness” (multimorbidity) (Table 2). This may seem different from the estimated prevalence of each component in the initial FRAIL study (fatigue, 20.1%; illness, 2.1%) [39], however in light of the diabetes background and the advanced age of our frail participants (57.8 vs. 75 years), an increase in multimorbidity prevalence can be reasonable in this study. In addition, studies have demonstrated that diabetes patients had a significantly higher risk of developing chronic fatigue than matched controls, and those with fatigue tend to have more severe functional limitations [40]. The association between hyperglycemia and fatigue may be explained by the co-existence of other diabetic symptoms, psychological distress from self-care, or glucose control variability [41, 42].

During the analysis of associations between each frailty component and outcomes, we found that only “Body weight loss” and “Resistance” impairment were consistently associated with adverse health outcomes and more healthcare utilization, while “Ambulation” was unrelated to adverse health outcomes (Table 5). The low number of diagnoses used to recognize impairment in “Ambulation” and the low prevalence of this frailty component might be plausible reasons to explain these findings. Alternatively, the constituents of healthcare utilization in this study are based more on acute care instead of subacute or long-term care, and that difficulty in ambulation may have a comparatively more prominent association with care types of the latter [43]. Nonetheless, it is evident that each frailty component influences either health outcomes or healthcare utilization.

Past studies that linked healthcare utilization and frailty mostly focused on generally older populations. Comans et al., using a community-based post-acute care cohort, identified that a higher degree of frailty predicted a higher likelihood of re-hospitalization and greater healthcare costs within 6 months, independent of other confounders [44]. In community-dwelling middle-aged to older adults, Blodgett et al. similarly found that frail index scores positively correlated with the risk of hospitalization, more physician visits and medications used [45]. In contrast, the influence of pre-frailty on healthcare utilization is rarely addressed in the literature. A large cross-sectional study in an Australian older population revealed a gradient effect between frailty severity and both hospital and non-hospital based services use [46], providing evidence for the influence of pre-frailty on healthcare utilization. However, a recent study discovered that developing pre-frailty was not associated with an increase in total healthcare utilization in a German cohort [47], rendering this relationship controversial. In the current study, we reported that the status of pre-frailty and frailty were both associated with higher healthcare utilization compared to non-frail patients with DM, in addition to their influence on patient survival. It is plausible that the differences in patient background illness severity account for this discrepancy, because we specifically focused on patients with DM while prior studies addressed older adults in general. It may be easier to detect meaningful differences in populations with higher incidence of outcomes of interest.

Based on our findings, the presence of frailty and even pre-frailty can lead to a higher risk of adverse health outcomes and greater healthcare utilization. Assessing frailty can assist in predicting patient outcomes and in allocating healthcare resource [48]. Moreover, interventions aiming to prevent or ameliorate frailty can offer the chance to reduce healthcare consumption. A recent study suggests that institution-wide frailty assessment can provide valuable information when allocating limited healthcare resources to nursing homes [49], and similar utility is likely demonstrable in patients with DM. Furthermore, care coordination and integration into routine practice has been shown to reduce the frequency of medical encounter among frail elderly, including unplanned hospitalization and medication costs [50]. There are also on-going studies examining the effect of individual-level frailty intervention on healthcare utilization [51]. We believe that frailty-targeted managements can be an important yet under-recognized approach for reducing healthcare resource consumption in DM patients, although further study is still needed for confirmation.

Prior studies reported that the prevalence of frailty in diabetes patients varied between 1 and 48% [11, 12, 52]; in our study, the prevalence of frailty was estimated at 0.3%, which was relatively lower than that reported by others. We propose that under-coding of the diagnoses allocated to the frailty components by physicians [53], the stricter criteria we imposed to identify frailty, and the adoption of the physical frail approach instead of the frail index, might partially account for this discrepancy, although more data are needed to support this conclusion. In addition, we enrolled incident type 2 DM patients instead of long-standing diabetic patients in this study (Fig. 1), and this may be another reason for the low frailty prevalence in our diabetic participants. Furthermore, the mean aDCSI score of our participants was 0.28, significantly lower than that of prevalent DM patients in Taiwan reported previously [18], lending support to the relatively minor diabetic severity and potentially lower prevalence of frailty among these patients.

Our study has its strengths and limitations. The large number of participants enrolled and the comprehensiveness of confounding variables included provide support to the credibility of our findings. Since we did not find any population-based study addressing the influence of frailty on healthcare utilization of diabetic patients, we believe that a study supporting the existence of such association in this population is important to fill the knowledge gap. We also showed that pre-frailty exhibited a similar association with higher healthcare utilization in addition to mortality in diabetes patients, a question rarely addressed before, and our results are expected to clarify the role of pre-frailty in the management of patients with DM. A more in-depth comparison between our findings and those of others shows that there can be differences in the magnitude of risk elevation conferred by frailty between diabetic patients and those with other illnesses (ex. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart failure). These issues warrant further investigation in the future. However, our study is limited by the lack of data from actual physical examinations including vial signs. The claim database in use did not contain information regarding laboratory profiles such as glycated hemoglobin, serum cholesterol or triglyceride levels, and obtaining an accurate history of smoking, alcohol consumption, or comorbidities with a low incidence was difficult. There could be important variables that failed to be considered during our analyses [54,55,56]. Most importantly, the definition of frailty was based on diagnostic groupings rather than a questionnaire survey, and this approach could suffer from a low sensitivity for detecting abnormalities. As an extended period was required for ascertaining the diagnosis presence in this study, it would be difficult to validate this frailty definition using physical assessment results, since the timing of physical assessment could not be determined. The reported prevalence of each frailty component might not be generalizable to other diabetic population, and extrapolation of our findings should be cautious. Although our findings should be independently confirmed, we believe that programs for early management of frailty and even pre-frailty might be beneficial to diabetes patients in the future [57].

Conclusion

Using a large representative cohort of patients with type 2 DM, we found that both pre-frailty and frailty increased the risk of long-term mortality and cardiovascular events, and significantly increased healthcare utilization compared to non-frail ones. We believe that management directed against pre-frailty and frailty can reduce healthcare spending in these patients, in addition to improving patient survival.

Abbreviations

- aDCSI:

-

adjusted diabetic complication severity index

- ADL:

-

activities of daily living

- CHS:

-

Cardiovascular Health Study

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- DM:

-

diabetes mellitus

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- ICD-9-CM:

-

International Classification of Disease-9-Clinical Modification

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- LHDB:

-

Longitudinal Cohort of Diabetes Patients database

- OAD:

-

oral anti-diabetic agents

References

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–57.

Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, MacKnight C, McDowell I, Hébert R, Hogan DB. A brief clinical instrument to classify frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 1999;353(9148):205–6.

Papachristou E, Wannamethee SG, Lennon LT, et al. Ability of self-reported frailty components to predict incident disability, falls, and all-cause mortality: results from a population-based study of older British men. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(2):152–7.

Herr M, Arvieu JJ, Robine JM, Ankri J. Health, frailty and disability after ninety: results of an observational study in France. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:166–75.

Sergi G, Veronese N, Fontana L, et al. Pre-frailty and risk of cardiovascular disease in elderly men and women: The Pro.V.A. Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(10):976–83.

Yu R, Morley JE, Kwok T, Leung J, Cheung O, Woo J. The effects of combinations of cognitive impairment and pre-frailty on adverse outcomes from a prospective community-based cohort study of older Chinese people. Front Med. 2018;5:50.

Serra-Prat M, Sist X, Domenich R, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to prevent frailty in pre-frail community-dwelling older people consulting in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):401–7.

de Miguel-Yanes JM, Jimenez-Garcia R, Hernandez-Barrera V, Mendez-Bailon M, de Miguel-Diez J, Lopez-de-Andres A. Impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus on in-hospital-mortality after major cardiovascular events in Spain (2002–2014). Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):126.

Jiang YD, Chang CH, Tai TY, Chen JF, Chuang LM. Incidence and prevalence rates of diabetes mellitus in Taiwan: analysis of the 2000–2009 nationwide health insurance database. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111(11):599–604.

Lu CL, Shen HN, Chen HF, Li CY. Epidemiology of childhood type 1 diabetes in Taiwan, 2003–2008. Diabet Med. 2014;31(6):666–73.

Chode S, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK, Morley JE. Frailty, diabetes, and mortality in middle-aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(8):854–9.

Liccini AP, Malmstrom TK. Frailty and sarcopenia as predictors of adverse health outcomes in persons with diabetes mellitus. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(9):846–51.

Sinclair AJ, Abdelhafiz AH, Rodríguez-Mañas L. Frailty and sarcopenia-newly emerging and high impact complications of diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31(9):1465–73.

Casanova F, Adingupu DD, Adams F, et al. The impact of cardiovascular co-morbidities and duration of diabetes on the association between microvascular function and glycaemic control. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):114.

Ulley J, Abdelhafiz AH. Frailty predicts adverse outcomes in older people with diabetes. Practitioner. 1800;2017(261):17–20.

Li P-I, Wang J-N, Guo H-R. A long-term quality-of-care score for predicting the occurrence of macrovascular diseases in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:72–80.

Ou H-T, Chang K-C, Li C-Y, Wu J-S. Risks of cardiovascular diseases associated with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and other antidiabetic drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes: a nation-wide longitudinal study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):41.

Chang H-Y, Weiner J, Richards T, Bleich S, Segal J. Predicting costs with diabetes complications severity index in claims data. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(4):213–9.

Chao C-T, Wang J, Wu H-Y, Huang J-W, Chien K-L. Age modifies the risk factor profiles for acute kidney injury among recently diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients: a population-based study. GeroScience. 2018;40(2):201–17.

Mohammedi K, Woodward M, Marre M, et al. Comparative effects of microvascular and macrovascular disease on the risk of major outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):95.

Van Kan GA, Rolland Y, Bergman H, Morley JE, Kritchevsky SB, Vellas B. The I.A.N.A. task force on frailty assessment of older people in clinical practice. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(1):29–37.

Chao C-T, Hsu Y-H, Chang P-Y, et al. Simple self-report FRAIL scale might be more closely associated with dialysis complications than other frailty screening instruments in rural chronic dialysis patients. Nephrology. 2015;20(5):321–8.

Chao C-T, Huang J-W, Chiang C-K. Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—the fatigue scale exhibits stronger associations with clinical parameters in chronic dialysis patients compared to other fatigue-assessing instruments. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1818.

Li Y, Zou Y, Wang S, et al. A pilot study of the FRAIL scale on predicting outcomes in Chinese elderly people with type 2 diabetes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(8):714-e7–12.

Faurot KR, Funk MJ, Pate V, et al. Using claims data to predict dependency in activities of daily living as a proxy for frailty. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(1):59–66.

Segal JB, Chang H-Y, Du Y, Walston JD, Carlson MC, Varadhan R. Development of a claims-based frailty indicator anchored to a well-established frailty phenotype. Med Care. 2017;55(7):716–22.

Hyun KD, Sebastian S. Measuring frailty using claims data for pharmacoepidemiologic studies of mortality in older adults: evidence and recommendations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(9):891–901.

Von Gunten CF, Ferris FD, Kirschner C, Emanuel LL. Coding and reimbursement mechanisms for physician services in hospice and palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(2):157–64.

Kuo YT, Chang TT, Muo CH, et al. Use of complementary traditional Chinese medicines by adult cancer patients in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17(2):531–41.

Verghese J, Wang C, Xue X, Holtzer R. Self-reported difficulty in climbing up or down stairs in nondisabled elderly. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(1):100–4.

Herman T, Inbar-Borovsky N, Brozgol M, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. The dynamic Gair index in healthy older adults: the role of stair climbing, fear of falling and gender. Gait Posture. 2009;29(2):237–41.

Chao CT, Hou CC, Wu VC, et al. The impact of dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury on long-term prognosis of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: nationwide population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e50675.

Chao CT, Tang CH, Cheng RW, Wang MY, Hung KY. Protein-energy wasting significantly increases healthcare utilization and costs among patients with chronic kidney disease: a propensity-score matched cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(9):1705–13.

Wang WJ, Chao CT, Huang YC, et al. The impact of acute kidney injury with temporal dialysis on the risk of fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(3):676–84.

Chao C-T, Lai H-J, Tsai H-B, Yang S-Y, Huang J-W. Frail phenotype is associated with distinct quantitative electroencephalographic findings among end-stage renal disease patients: an observational study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):277.

Lin TC, Solomon DH, Tedeschi SK, Yoshida K, Kao Yang YH. Comparative risk of cardiovascular outcomes between topical and oral nonselective NSAIDs in Taiwanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(11):e006874.

Kim DH, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Lipsitz LA, Rockwood K, Avorn J. Measuring frailty in medicare data: development and validation of a claims-based frailty index. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(7):980–7.

Wen Y-C, Chen L-K, Hsiao F-Y. Predicting mortality and hospitalization of older adults by the multimorbidity frailty index. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0187825.

Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(7):601–8.

Goedendorp MM, Tack CJ, Steggink E, Bloot L, Bazelmans E, Knoop H. Chronic fatigue in type 1 diabetes: highly prevalent but not explained by hyperglycemia or glucose variability. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):73–80.

Hanjong P, Chang P, Laurie Q, Cynthia F. Glucose control and fatigue in type 2 diabetes: the mediating roles of diabetes symptoms and distress. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(7):1650–60.

Mohammedi K, Woodward M, Hirakawa Y, et al. Presentations of major peripheral arterial disease and risk of major outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: results from the ADVANCE-ON study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):129.

Freeman S, Armstrong JJ, Tyas SL, Neufeld E. Clinical characteristics and patterns of health deficits of centenarians receiving home care and long-term care services. Exp Gerontol. 2017;99:46–52.

Comans TA, Peel NM, Hubbard RE, Mulligan AD, Gray LC, Scuffham PA. The increase in healthcare costs associated with frailty in older people discharged to a post-acute transition care program. Age Ageing. 2016;45(2):317–20.

Blodgett JM, Theou O, Howlett SE, Wu FCW, Rockwood K. A frailty index based on laboratory deficits in community-dwelling men predicted their risk of adverse health outcomes. Age Ageing. 2016;45(4):463–8.

Dent E, Dal Grande E, Price K, Taylor AW. Frailty and usage of health care systems: results from the South Australian Monitoring and Surveillance System (SAMSS). Maturitas. 2017;104:36–43.

Hajek A, Bock J-O, Saum K-U, et al. Frailty and healthcare costs—longitudinal results of a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2018;47(2):233–41.

Wu IC, Lin CC, Hsiung CA. Emerging roles of frailty and inflammaging in risk assessment of age-related chronic diseases in older adults: the intersection between aging biology and personalized medicine. Biomedicine. 2015;5(1):1.

Cesari M, Costa N, Hoogendijk EO, Vellas B, Canevelli M, Perez-Zepeda MU. How the frailty index may support the allocation of health care resources: an example from the INCUR study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(5):448–50.

Robusto F, Bisceglia L, Petrarolo V, et al. The effects of the introduction of a chronic care model-based program on utilization of healthcare resources: the results of the Puglia care program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):377.

Landi F, Cesari M, Calvani R, et al. The “Sarcopenia and Physical fRailty IN older people: multicomponent Treatment strategies” (SPRINTT) randomized controlled trials: design and methods. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017;29(1):89–100.

Yanase T, Yanagita I, Muta K, Nawata H. Frailty in elderly diabetes patients. Endocr J. 2017;65(1):1–11.

Wilchesky M, Tamblyn RM, Huang A. Validation of diagnostic codes within medical services claims. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(2):131–41.

Noh M, Kwon H, Jung CH, et al. Impact of diabetes duration and degree of carotid artery stenosis on major adverse cardiovascular events: a single-center, retrospective, observational cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):74.

Bots SH, van der Graaf Y, Nathoe HM, et al. The influence of baseline risk on the relation between HbA1c and risk for new cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes and symptomatic cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):101.

Tao X, Li J, Zhu X, et al. Association between socioeconomic status and metabolic control and diabetes complications: a cross-sectional nationwide study in Chinese adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:61.

Mallery LH, Ransom T, Steeves B, Cook B, Dunbar P, Moorhouse P. Evidence-informed guidelines for treating frail older adults with type 2 diabetes: from the Diabetes Care Program of Nova Scotia (DCPNS) and the Palliative and Therapeutic Harmonization (PATH) program. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(11):801–8.

Authors’ contributions

Study design: CTC, KLC; Data collection and analysis: CTC, JW, KLC; Article drafting: CTC, JW, KLC; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the assistants from the T1 research center of the National Taiwan University Hopital BeiHu branch, and thank the COGENT study group members including Hung-Bin Tsai, Chih-Kang Chiang, Jenq-Wen Huang, Ding-Cheng Chan, and Kuan-Yu Hung.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to declare in relation to this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board of National Taiwan University Hospital (No. 201802063W) approved the current study; the study protocol adheres to the declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived due to data anonymity.

Funding

The study is financially sponsored by National Taiwan University Hospital BeiHu branch, and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 106-2314-B-002-132-MY2). The sponsors have no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, and result interpretation of this study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Sensitivity analyses consisting of different ranges of data for identifying frailty.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chao, CT., Wang, J., Chien, KL. et al. Both pre-frailty and frailty increase healthcare utilization and adverse health outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 17, 130 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0772-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0772-2