Abstract

Background

The soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products (sRAGE) has been suggested that it acts as a decoy for capturing advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and inhibits the activation of the oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways. Lung AGEs/sRAGE is increased in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). The objective of the study was to evaluate the AGEs and sRAGE levels in serum as a potential biomarker in IPF.

Methods

Serum samples were collected from adult patients: 62 IPF, 22 chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (cHP), 20 fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia (fNSIP); and 12 healthy controls. In addition, 23 IPF patients were re-evaluated after 3-year follow-up period. Epidemiological and clinical features were recorded: age, sex, smoking habits, and lung function. AGEs and sRAGE were evaluated by ELISA, and the results were correlated with pulmonary functional test values.

Results

IPF and cHP groups presented a significant increase of AGE/sRAGE serum concentration compared with fNSIP patients. Moreover, an inverse correlation between AGEs and sRAGE levels were found in IPF, and serum sRAGE at diagnosis correlated with FVC and DLCO values. Additionally, changes in serum AGEs and sRAGE correlated with % change of FVC, DLCO and TLC during the follow-up. sRAGE levels below 428.25 pg/ml evolved poor survival rates.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate that the increase of AGE/sRAGE ratio is higher in IPF, although the levels were close to cHP. AGE/sRAGE increase correlates with respiratory functional progression. Furthermore, the concentration of sRAGE in blood stream at diagnosis and follow-up could be considered as a potential prognostic biomarker.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most frequent form of fibrotic interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), which presents a variable outcome and is generally fatal within 2–4 years from diagnosis [1]. Histologically, IPF is characterized by an usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern; where honeycombing areas with collagen deposition and fibroblast foci are situated next to structurally preserved areas [2]. Advances in the knowledge of the pathogenesis have been focused in integrating the different factors involved in IPF with the purpose of improving the diagnosis, management and treatment [3].

In clinical practice, some fibrosing lung entities such as chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (cHP) and fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (fNSIP) represent a challenge in the differential diagnosis for IPF as there are clinical and radiological similarities [4,5,6,7,8]. Even after an invasive procedure such as lung biopsy, it occasionally remains difficult to differentiate IPF from cHP [9, 10]. Though some features may be similar to IPF [11], the prognosis is better for fNSIP and cHP, and the treatment differs [12]. The proteomic analysis could be a useful tool to differentiate between these entities and to reach an accurate diagnosis, attempting to avoid invasive diagnostic procedures [13]. In the last decades, serum and broncoalveolar biological markers have been extensively studied in IPF for diagnosis and prognosis [14,15,16,17]. However, despite the progress in identifying new biomolecules involved in IPF pathogenesis, none improve the differential diagnosis and monitoring of the clinical course [18].

Recent studies have reported the implication of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and their receptor (RAGE) with IPF and other fibrotic ILDs [19]. In fact, a previous study within our group reported an AGE-RAGE imbalance in lung tissue from IPF patients compared to controls [20]. The RAGE is an immunoglobulin superfamily protein [21] implicated in the maintenance of alveolar structures in lung tissue [22] and the development and differentiation of Type I pneumocytes [23]. Its soluble form (sRAGE) is secreted directly to the extracellular matrix (ECM) through loss of its transmembrane region by cleavage [24, 25]. This is of particular interest because sRAGE has been proposed as an AGE decoy [26]. Some groups have suggested that sRAGE bind AGEs, blocking the cell signaling pathway of AGEs or attenuating their effects [27,28,29]. AGEs are the result of non-enzymatic reactions between a reducing sugar monosaccharides with a free amino group of proteins [30], widely studied in oxidative stress, inflammation and aging [31, 32]. AGEs also contribute to abnormal wound healing by acting on signaling pathway in cells [33] and ECM protein cross-links [34]; these changes may alter the physicochemical properties of collagen fibers modifying the tissue stiffness [35]. Given that RAGE is highly expressed in lung tissue [36], sRAGE could be a possible serum or plasma biomarker to study the pulmonary disorder.

Some studies of blood [37] and bronchoalveolar lavage [38] indicate a correlation between lung injury and the levels of sRAGE [39,40,41]. Nevertheless, there is scarce information about the specificity of AGE-RAGE imbalance in IPF [42, 43]. Therefore, our study aims to evaluate the potential utility of serological AGEs and sRAGE levels in IPF.

Methods

Ethical statement and patient recruitment

Patients were recruited in the outpatient Unit of ILDs from University Hospital of Bellvitge: 62 IPF, 22 cHP, and 20 fNSIP. The patient’s diagnosis was discussed in the multidisciplinary committee and was established in accordance with the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society criteria [5, 12, 44]. Twelve healthy subjects age-matched were recruited as control. The inclusion criteria of healthy volunteers were the absence of chronic illness and pulmonary functional test abnormalities. We collected serum samples after 3 years from 23 IPF patients in order to analyze the changes of AGEs-sRAGE levels and the progression of the disease. Lung transplantation and mortality were reported. These patients and those that return to their original care centers were excluded for the second serological evaluation.

This observational prospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital of Bellvitge (CEIC, ref. PR082/15) and all patients signed the written informed consent before their inclusion.

Pulmonary function test (PFT)

Spirometry, lung volume, and Diffusing Capacity of Lung for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO) were measured in the Medisoft® bodybox Plethysmograph at the PFT laboratory. Three reproducible spirometry measurements were performed (with a difference of less than 150 ml between each one) to obtain the Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) and Total Lung Capacity (TLC). Two maneuvers were recorded to register the best value by DLCO single-breath technique.

Sample collection, processing and measurement

Peripheral blood samples were collected from participants in a BD Vacutainer® SST™ tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA), and serum faction were obtained using standardized procedures. AGE and sRAGE were measured by specific commercial ELISA kit; Human RAGE Quantikine ELISA Kit (DRG00; R&D Systems, USA) and Human AGEs ELISA Kit (CSB-E09412h; Cusabio Biotech Co., China), following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean [SD] or median [interquartile range] and were compared using one-way ANOVA or Student’s t test, followed by the appropriate post hoc analysis.

To evaluate the power of AGEs/sRAGE to discriminate between the fibrotic ILDs, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed: the levels of AGE and sRAGE in blood serum were considered as a continuous variable and the diagnostic classification was accepted as a dichotomous variable. Cutoff points were calculated by the ROC curves with the highest possible sensitivity and specificity, and their discriminative potential was quantified following 3 different diagnostic accuracy measures: Diagnostic effectiveness (Accuracy), Likelihood ratio for positive test results (LR+), and Youden’s index (J). To determine the serum levels that predict 3-year survival rates in the whole IPF cohort, ROC curve analysis was also performed, and the rate was estimated by Kaplan–Meier analysis using log-rank test as statistic contrast. In addition, Pearson’s correlations were performed to test the relation among PFT, sRAGE and AGE serum levels at the beginning of the study and at the end of the 3-year follow-up. Statistical software SPSS statistic 24 (IBM, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Significant differences were accepted when the p value was < 0.05 (*) or < 0.01 (**).

Results

Clinical characteristics

Clinical features of IPF, cHP, fNSIP and control groups are included in Table 1. IPF patients were predominantly males and former smokers. No statistical differences among the studied groups were found in age, pack-years, nor smoking cessation. Regarding PFTs, control subjects showed better results in the percentage of predicted FVC, DLCO and TLC than fibrotic ILDs, as expected (p < 0.01).

AGEs and sRAGEs serum concentration in pulmonary fibrosis

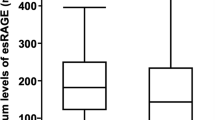

AGEs levels were significantly higher in serum samples from IPF and cHP compared with control and fNSIP patients (p < 0.01). There were no statistical differences in AGEs serum levels between IPF and cHP groups, and no differences were observed when fNSIP was compared to control (Fig. 1a).

ELISA of AGEs and sRAGE in serum blood from controls (CNT) and fibrosing ILDs. a and b ELISA for total AGEs and sRAGE showed significant differences between control group with IPF and cHP (*p < 0.01), and differences between fNSIP patients with IPF (#p < 0.01) and cHP (§p < 0.01) groups. However, there were no significant differences between IPF with cHP and control with fNSIP. c AGEs/sRAGE ratio estimated by ELISA was greater in IPF and cHP groups compared with control (*p < 0.01). The ratio also allowed to distinguish between IPF patients with cHP and fNSIP (#p < 0.05), and cHP with fNSIP group (§p < 0.01), whereas this did not distinguish between control and fNSIP patients. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA following by the appropriate post-hoc analysis

On the other hand, a significant decrease in sRAGE concentration was observed in serum samples from IPF and cHP patients compared to fNSIP and control donors (p < 0.01). There were no significant differences comparing IPF and cHP (Fig. 1b).

The serum AGE/sRAGE ratio of each patient was analyzed from the ELISA results. An increase of 4.20 and 4.48-fold was observed in IPF patients compared with fNSIP and control subjects, respectively (p < 0.01). Furthermore, the ratio was statistically significant higher in IPF patients than cHP patients (p < 0.05). In addition, the AGE/sRAGE ratio was 2.84-fold higher in cHP as compared to fNSIP (p < 0.01). AGE/sRAGE ratio in fNSIP was similar to the control group (Fig. 1c).

AGE and sRAGE as a discriminative factor between IPF and fNSIP

We performed a ROC curve analysis to evaluate the potential IPF specificity of AGEs and sRAGE levels in blood serum (Additional file 1). The results showed that serum sRAGE and AGEs levels present a high capacity to differentiate IPF patients from fNSIP (AUC = 0.801 and 0.879, respectively), and between cHP and fNSIP patients (AUC = 0.887 and 0.883, respectively) (Fig. 2a, b). Furthermore, the AGE/sRAGE ratio also distinguished between fNSIP and IPF (AUC = 0.987, CI = 0.959–1.000), and between cHP and fNSIP (AUC = 0.882, CI = 0.766–0.998).

ROC curve for total AGEs, sRAGE levels and Ages/sRAGE ratio. a AGEs and sRAGE showed a good capability to differentiate between IPF patients and fNSIP group (AUC = 0.879 and 0.801, respectively), whereas the AGEs/sRAGE ratio had higher predictable capability (AUC 0.987, CI = 0.959–1.000) to discriminate between both. b Comparing cHP and fNSIP, all the three indicators (AGEs, sRAGE levels and AGE/sRAGE ratio) showed AUC values quite good to be considered diagnostic tests (AGEs = 0.883, sRAGE = 0.887, Ratio = 0.882). Data were evaluated by ROC analyses; blood serum levels of AGE and sRAGE were considered as a continuous variable, and the diagnostic classification was accepted as a dichotomous variable

On the other hand, AGEs and sRAGE levels did not demonstrate capability to differentiate IPF and cHP (AUC = 0.383 and 0.507, respectively), while ratio showed very low differential power (AUC = 0.713, CI = 0.569–0.856).

To evaluate the discriminative potential of AGEs, sRAGE and AGE/sRAGE, optimal cut-off points were obtained from the ROC curve. Table 2 showed that AGEs/sRAGE ratio had a higher diagnostic effectiveness (accuracy = 98.28%, LR+ = 17.00, J = 0.94) than serum levels of AGEs and sRAGE separate values to distinguish between IPF and fNSIP patients. Moreover, although the diagnostic accuracy and the Youden’s index of the three parameters were quite similar, serum levels of AGEs were more appropriate than sRAGE and the AGEs/sRAGE ratio to differentiate between cHP and fNSIP (LR+ = 14.67, 4.86, and 6.38; respectively).

AGE and sRAGE correlation with PFTs

Pearson’s test showed that increased levels of AGEs correlated with lower sRAGE in IPF patients (r = − 0.541, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3a). Meanwhile, cHP patients also showed a negative correlation (r = − 0.496, p < 0.05), fNSIP patients did not show any significant correlation (Additional file 2).

Pearson’s correlation between sRAGE, AGEs and PFT in IPF patients. a Results showed a negative relationship between sRAGE and AGEs in serum samples from IPF patients. b, c, d There was a positive correlation between sRAGE serum levels and percentages values of FVC, DLCO and TLC in IPF samples. The lineal relationship between the variables was analyzed by Pearson’s correlations coefficient

Pearson’s test also showed that lower levels of sRAGE in serum samples from IPF patients correlated with worse lung functionalism: % predicted of FVC (r = 0.447, p < 0.01), DLCO (r = 0.466, p < 0.01) and TLC (r = 0.315; p < 0.05) (Fig. 3b, c, d). However, the concentration of AGEs did not show any correlation with PFTs in IPF (data not shown). Regarding cHP and fNSIP samples, there was also a positive correlation between sRAGE and PFTs, whereas AGEs levels did not show any correlation in either entity (cHP and fNSIP).

AGEs-sRAGE concentration in the follow-up of IPF patients

Twenty-three IPF patients were re-evaluated 3-years after their inclusion. Table 3 show a decrease in the lung functional values, with a significant decrease in the mean FVC. Regarding ELISA analyses, only sRAGE serum levels showed a significant decrease between the basal level and 3-years after (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4a).

Serum levels and predictive capability of sRAGE for 3-year survival rates. a Results showed a significant decrease of sRAGE in IPF patients beyond 3-years. b Kaplan–Meier analysis showed IPF patients with sRAGE levels in serum under 428.25 pg/ml had lower survival rate (p = 0.014) at 3-yr follow-up. Comparison of AGEs/sRAGE levels in follow-up were analyzed by Paired sample t-test, the threshold of sRAGE levels in blood were calculated by ROC analysis and survival rate was estimated by Kaplan–Meier analysis using log-rank test as statistic contrast

In addition, the ROC analysis of the whole IPF group showed sRAGE levels as a reliable predictor of the 3-year follow-up (AUC = 0.724, 95% CI = 0.586–0.863, p < 0.01). Survival estimation by Kaplan–Meier was lower in IPF patients with serum concentrations of sRAGE under 428.25 pg/mL at the basal level (p = 0.014) (Fig. 4b).

Furthermore, we correlated the changes in serum sRAGE and AGEs from IPF patients adjusted over time (Δ ELISA in a month = [ELISA final – ELISA initial]/month) with the percentage of change of lung function in the same interval (change of % predicted PFT = [PFT final – PFTs initial]/month). The results show a relationship between variations in sRAGE, AGEs and their ratio levels with the lung functional values (% predicted) of FVC, TLC and DLCO (Table 4). IPF patients with a decrease in sRAGE serum levels during the follow-up usually showed a significant decline in % predicted DLCO as well (Fig. 5a). On the other hand, an increase of AGEs serum levels was highly associated with a DLCO decline, while no changes in DLCO associated no changes in AGEs serum levels (Fig. 5b).

Correlation between changes in DLCO and differences in sRAGE-AGEs levels in IPF patients. a In IPF patients, a decline of DLCO was related with a decrease of sRAGE in serum (r = 0.555, p < 0.01). b and c On the contrary, AGEs levels and the AGEs/sRAGE ratio were negatively correlated with the percentage of changes in DLCO in IPF patients (r = − 0.747 and − 0704, respectively, p < 0.01), meaning poor lung function in patients with an increase of AGEs-sRAGE imbalance over time. The changes in serum sRAGE and AGEs and lung function from IPF patients was calculated, adjusting over time: Δ ELISA in a month = [ELISA final – ELISA initial]/month; change of % predicted PFT = [PFT final – PFTs initial]/month. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were performed to analyze the lineal relationship between the variables

With regards to the AGEs/sRAGE ratio, a negative correlation with % predicted DLCO was observed as well. Therefore, IPF patients with an increase of the AGEs/sRAGE ratio had a more rapid decline in DLCO (Fig. 5c). Furthermore, an increment of AGEs in serum was correlated with a loss of their receptor in IPF patients, maintaining a negative correlation over time (Additional file 3).

Discussion

Some reports have shown an association between the blood sRAGE levels and the state of alveolar epithelium and lung injury [40, 45, 46]. Furthermore, previous results from our group found AGEs increased in IPF lungs [20]. The present results suggest that serum AGEs and sRAGE are different in IPF than in fNSIP, and their ratio is even higher than in cHP, which could be a useful information for the differential diagnosis of these fibrotic ILDs. Moreover, low levels of sRAGE at diagnosis predict poor survival in IPF. Finally, the AGE and RAGE changes correlate with lung functional changes over time.

While the radiological fNSIP pattern may be similar to IPF, the histological pattern is completely different. Therefore, lung biopsy is required in some cases to differentiate both entities. In this case, finding biological lung markers that could be measured in blood samples to differentiate both entities would be of interest for the clinical practice. Serum AGEs and sRAGE show a completely different pattern in IPF and fNSIP, probably due to the lack of fibroblastic foci and honeycombing in fNSIP lungs and the pathogenic differences [11]. Lung RAGEs are expressed in alveolar epithelial cells and lungs with usual interstitial pneumonia pattern show lower RAGEs expression than NSIP lungs [20]. Manichaiku et al. showed lower plasma levels in IPF and HP patients than control subjects [47]. The decrease of RAGEs is not present in all fibrotic ILDs; fNSIP presents serum RAGEs and AGEs similar to normal subjects.

Lungs are the main source of RAGEs in healthy conditions [36]. Several studies concluded that cleaving full length RAGE (FL-RAGE), the transmembrane form, is the main way to produce the soluble form of alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) from healthy human lungs [48]. This might suggest that decrease in sRAGE found in IPF patients could be interpreted as a lack of RAGE synthesis or the loss of AECs. Thus, variations in the serum sRAGE levels would reflect the possible changes in lung function. The association between serum sRAGE and PFTs, as well as the changes over time would support this hypothesis. Longitudinal changes in FVC and DLCO have been found to have important prognostic value in IPF [49]. However, predicting prognosis at diagnosis remains a challenge. In our IPF cohort, patients with lower levels of sRAGE at the beginning of this study (under 428.25 pg/mL) showed worse lung-transplant progression free survival rate at 3 years, in accordance with previous observations from Yamaguchi and colleagues [37].

The decrease of sRAGE might be related to the progressive loss of alveolar structures in lung fibrosis lung. Chronic lung diseases that cause a progressive destruction of the alveolar structures such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) showed low levels of sRAGE compared with controls [39, 50]. Those results have been correlated with a deterioration in lung function over time. Similarly, mechanical damage of lung showed low levels of sRAGE [41, 51]. On the other hand, the downregulation of RAGE has also been related to several pro-fibrotic pathways [52, 53]. There are some reports that showed a predisposition to develop a spontaneous pulmonary fibrosis in RAGE null mice [54]. All these findings suggest that the destruction of alveolar structures by fibrotic changes might favor the loss of RAGEs in IPF patients, and this downregulation of sRAGE, at the same time, could favor the fibrosis progression.

Regarding AGEs levels in serum, although a significant increase has been found in IPF and cHP compared to fNSIP, the measurement in the IPF group at the beginning of the study was not associated with pulmonary functional values. However, changes in AGEs levels over time were associated with FVC, TLC and DLCO decline. AGEs are increased in IPF lungs and have been associated with myofibroblast formation and ECM stiffness in vitro [55]. In addition, if sRAGE decreases, the pro-fibrotic effect of AGEs could increase due to the decreased decoy effect [56]. Our results also showed that those IPF patients with higher AGEs/sRAGE ratio showed a faster decline in DLCO. These findings indicate that an increase of AGEs or the AGEs/sRAGE ratio might indicate the degree of remodeling changes due to pulmonary fibrosis.

Some limitations of the study are the small number of the included cases in each group and the lack of validating cohort. Furthermore, no other possible biomarkers have been measured in our cohort in order to compare the differences or supplementary value for diagnostic and prognostic purposes. However, the results are useful for inclusion of this biomarker in longitudinal multicenter studies to evaluate potential biomarkers in fibrotic ILDs.

In the last few years, extensive reviews had been done to evaluate the multiple potential serum markers proposed, some of them implied in ECM remodeling or AEC dysfunction, suggesting a much better diagnostic accuracy and practicality when they were evaluated together [57,58,59]. Our model base on AGEs-sRAGE estimation and ratio also emphasizes the need to mix biomarkers for improving predictive power.

Conclusions

In conclusion, these results demonstrate that the ratio AGEs/sRAGE could be considered as a new potential serum biomarker for aiding in the differential diagnosis between the most common fibrosing ILDs, although a prospective multicenter study for validating this pivotal results would be required. Furthermore, serum sRAGE level is a prognostic biomarker in IPF.

Abbreviations

- AECs:

-

Alveolar Epithelial Cells

- AGEs:

-

Advanced glycation end-products

- AUC:

-

Area Under the Curve

- cHP:

-

Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DLCO:

-

Diffusing Capacity for Carbon Monoxide

- ECM:

-

Extracellular Matrix

- FL-RAGE:

-

Full-length RAGE

- fNSIP:

-

Fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia

- FVC:

-

Forced Vital Capacity

- ILDs:

-

Interstitial Lung Diseases

- IPF:

-

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- J:

-

Youden’s index

- LR+:

-

Likelihood ratio for positive test results

- PFT:

-

Pulmonary Function Test

- RAGE:

-

Receptor for AGEs

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- sRAGE:

-

Soluble RAGE

- TLC:

-

Total Lung Capacity

- UIP:

-

Usual Interstitial Pneumonia

References

Buendía-Roldán I, Mejía M, Navarro C, Selman M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical behavior and aging associated comorbidities. Respir Med. 2017;129:46–52.

Lynch JP, Huynh RH, Fishbein MC, Saggar R, Belperio JA, Weigt SS. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: epidemiology, clinical features, prognosis, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;37:331–57.

Daccord C, Maher TM. Recent advances in understanding idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. F1000Research. 2016;5:1046.

Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Cool CD, Tuder RM, King TE, Brown KK. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis as the sole histologic expression of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Med. 2002;112:490–3.

Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TE, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:733–48.

Grunes D, Beasley MB. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a review and update of histologic findings. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66:888–95.

Spagnolo P, Rossi G, Cavazza A, Bonifazi M, Paladini I, Bonella F, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a comprehensive review. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2015;25:237–50.

Nathan SD, Brown AW, King CS. Diseases that mimic idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. In: Guide to clinical Management of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 33–41.

Takemura T, Akashi T, Kamiya H, Ikushima S, Ando T, Oritsu M, et al. Pathological differentiation of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis/usual interstitial pneumonia. Histopathology. 2012;61:1026–35.

Morell F, Villar A, Montero MÁ, Muñoz X, Colby TV, Pipvath S, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis in patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a prospective case-cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:685–94.

Glaspole I, Goh NSL. Differentiating between IPF and NSIP. Chron Respir Dis. 2010;7:187–95.

Vasakova M, Morell F, Walsh S, Leslie K, Raghu G. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: perspectives in diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:680–9.

Vasakova M, Poletti V. Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases involve different pathogenic pathways with similar outcomes. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffus Lung Dis. 2015;32:246–50.

van den Blink B, Wijsenbeek MS, Hoogsteden HC. Serum biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23:515–20.

Ley B, Brown KK, Collard HR. Molecular biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. AJP Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307:L681–91.

Guiot J, Moermans C, Henket M, Corhay J-L, Louis R. Blood biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung. 2017;195:273–80.

Drakopanagiotakis F, Wujak L, Wygrecka M, Markart P. Biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2018;69:404–21.

Maher TM. PROFILEing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: rethinking biomarker discovery. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22:148–52.

Oczypok EA, Perkins TN, Oury TD. All the “RAGE” in lung disease: the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is a major mediator of pulmonary inflammatory responses. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2017;23:40–9.

Machahua C, Montes-Worboys A, Llatjos R, Escobar I, Dorca J, Molina-Molina M, et al. Increased AGE-RAGE ratio in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2016;17:144.

Hudson BI, Lippman ME. Targeting RAGE signaling in inflammatory disease. Annu Rev Med. 2018;69:349–64.

Uchida T, Shirasawa M, Ware LB, Kojima K, Hata Y, Makita K, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products is a marker of type I cell injury in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1008–15.

Katsuoka F, Kawakami Y, Arai T, Imuta H, Fujiwara M, Kanma H, et al. Type II alveolar epithelial cells in lung express receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:512–6.

Hudson BI, Carter AM, Harja E, Kalea AZ, Arriero M, Yang H, et al. Identification, classification, and expression of RAGE gene splice variants. FASEB J. 2008;22:1572–80.

Raucci A, Cugusi S, Antonelli A, Barabino SM, Monti L, Bierhaus A, et al. A soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is produced by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound form by the sheddase a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10). FASEB J. 2008;22:3716–27.

Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. Soluble RAGE: therapy and biomarker in unraveling the RAGE axis in chronic disease and aging. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1379–86.

Tae HJ, Kim JM, Park S, Tomiya N, Li G, Wei W, et al. The N-glycoform of sRAGE is the key determinant for its therapeutic efficacy to attenuate injury-elicited arterial inflammation and neointimal growth. J Mol Med. 2013;91:1369–81.

Izushi Y, Teshigawara K, Liu K, Wang D, Wake H, Takata K, et al. Soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products attenuates inflammatory pathogenesis in a rat model of lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. J Pharmacol Sci. 2016;130:226–34.

Blondonnet R, Audard J, Belville C, Clairefond G, Lutz J, Bouvier D, et al. RAGE inhibition reduces acute lung injury in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7208.

Ott C, Jacobs K, Haucke E, Navarrete Santos A, Grune T, Simm A. Role of advanced glycation end products in cellular signaling. Redox Biol. 2014;2:411–29.

Byun K, Yoo YC, Son M, Lee J, Jeong GB, Park YM, et al. Advanced glycation end-products produced systemically and by macrophages: a common contributor to inflammation and degenerative diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;177:44–55.

Chaudhuri J, Bains Y, Guha S, Kahn A, Hall D, Bose N, et al. The role of advanced glycation end products in aging and metabolic diseases: bridging association and causality. Cell Metab. 2018;28:337–52.

Sukkar MB, Ullah MA, Gan WJ, Wark PAB, Chung KF, Hughes JM, et al. RAGE: a new frontier in chronic airways disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:1161–76.

Avery NCC, Bailey AJJ. The effects of the Maillard reaction on the physical properties and cell interactions of collagen. Pathol Biol. 2006;54:387–95.

Gautieri A, Passini FS, Silván U, Guizar-Sicairos M, Carimati G, Volpi P, et al. Advanced glycation end-products: mechanics of aged collagen from molecule to tissue. Matrix Biol. 2017;59:95–108.

Mukherjee TK, Mukhopadhyay S, Hoidal JR. Implication of receptor for advanced glycation end product (RAGE) in pulmonary health and pathophysiology. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;162:210–5.

Yamaguchi K, Iwamoto H, Horimasu Y, Ohshimo S, Fujitaka K, Hamada H, et al. AGER gene polymorphisms and soluble receptor for advanced glycation end product in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. 2017;22:965–71.

Willems S, Verleden SE, Vanaudenaerde BM, Wynants M, Dooms C, Yserbyt J, et al. Multiplex protein profiling of bronchoalveolar lavage in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Ann Thorac Med. 2013;8:38.

Iwamoto H, Gao J, Pulkkinen V, Toljamo T, Nieminen P, Mazur W. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products and progression of airway disease. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:68.

Yonchuk JG, Silverman EK, Bowler RP, Agustí A, Lomas DA, Miller BE, et al. Circulating soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) as a biomarker of emphysema and the RAGE axis in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:785–92.

Negrin LL, Halat G, Prosch H, Hüpfl M, Hajdu S, Heinz T. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products quantifies lung injury in Polytraumatized patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:1587–93.

Inghilleri S, Morbini P, Campo I, Zorzetto M, Oggionni T, Pozzi E, et al. Factors influencing oxidative imbalance in pulmonary fibrosis: an immunohistochemical study. Pulm Med. 2011;2011:421409.

Kyung SY, Byun KH, Yoon JY, Kim YJ, Lee SP, Park JW, et al. Advanced glycation end-products and receptor for advanced glycation end-products expression in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and NSIP. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;7:221–8.

Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824.

Jabaudon M, Blondonnet R, Roszyk L, Pereira B, Guérin R, Perbet S, et al. Soluble forms and ligands of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: an observational prospective study. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135857.

Hoonhorst SJM, Lo Tam Loi AT, Pouwels SD, Faiz A, Telenga ED, van den Berge M, et al. Advanced glycation endproducts and their receptor in different body compartments in COPD. Respir Res. 2016;17:46.

Manichaikul A, Sun L, Borczuk AC, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Farber EA, Mathai SK, et al. Plasma soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:628–35.

Ohlmeier S, Mazur W, Salmenkivi K, Myllärniemi M, Bergmann U, Kinnula VL. Proteomic studies on receptor for advanced glycation end product variants in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2010;4:97–105.

Cottin V, Hansell DM, Sverzellati N, Weycker D, Antoniou KM, Atwood M, et al. Effect of emphysema extent on serial lung function in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1162–71.

Wu L, Ma L, Nicholson LFB, Black PN. Advanced glycation end products and its receptor (RAGE) are increased in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2011;105:329–36.

Benjamin JT, Van der Meer R, Slaughter JC, Steele SRN, Plosa EJ, Sucre JM, et al. Inverse relationship between soluble RAGE and risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:1083–6.

Ding H, Ji XH, Chen R, Ma T, Tang Z, Fen Y, et al. Antifibrotic properties of receptor for advanced glycation end products in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;35:34–41.

Song JS, Kang CM, Park CK, Yoon HK, Lee SY, Ahn JH, et al. Inhibitory effect of receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) on the TGF-β-induced alveolar epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Exp Mol Med. 2011;43:517–24.

Englert JM, Hanford LE, Kaminski N, Tobolewski JM, Tan RJ, Fattman CL, et al. A role for the receptor for advanced glycation end products in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:583–91.

Vicens-Zygmunt V, Estany S, Colom A, Montes-Worboys A, Machahua C, Sanabria AAJ, et al. Fibroblast viability and phenotypic changes within glycated stiffened three-dimensional collagen matrices. Respir Res. 2015;16:82.

Prasad K. Low levels of serum soluble receptors for advanced glycation end products, biomarkers for disease state: myth or reality. Int J Angiol. 2014;23:11–6.

Rosas IO, Richards TJ, Konishi K, Zhang Y, Gibson K, Lokshin AE, et al. MMP1 and MMP7 as potential peripheral blood biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e93.

Hamai K, Iwamoto H, Ishikawa N, Horimasu Y, Masuda T, Miyamoto S, et al. Comparative study of circulating MMP-7, CCL18, KL-6, SP-A, and SP-D as disease markers of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:1–8.

Jenkins RG, Simpson JK, Saini G, Bentley JH, Russell AM, Braybrooke R, et al. Longitudinal change in collagen degradation biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an analysis from the prospective, multicentre PROFILE study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:462–72.

Acknowledgments

The author wants to thank Jose Palma from Hospital of Bellvitge for helping in the management of PFTs, and Jessica Germaine Schull for correcting the spelling.

Funding

This research was supported by the Spanish Pneumology and Thoracic Surgeon Society (SEPAR, 010/2017), the Catalan Pneumology Society (SOCAP), the Catalan Foundation of Pulmonology (FUCAP), and the Institute of Health Carlos III (ISCIII, PI15/00710), co-funded by FEDER funds/European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) – “a Way to Build Europe”. We thank CERCA Programme / Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CM set up and performed the several assessments, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. AMW oversaw the experimental assays and revised the draft of the manuscript. LPC prepared the samples, accomplished the database of the patients. RB handled and prepared the samples. MMM conceived, designed and oversaw the experiments, and helped to draft the manuscript. VVZ conceived the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethic Committee of Clinical Research (CEIC, ref. PR082/15) in Bellvitge University Hospital (l’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spain), and all patients agreed to participate and provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have any competing interests (both financial and non-financial) related to this manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

ROC statistics for sRAGE and AGE serum levels. AGE: advanced glycation end-product, AUC: area under the curve, cHP: chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, fNSIP: fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia, CI: confidence interval, IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sRAGE: soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products, ROC: Receiver operating characteristic. (*) p-value < 0.05, (**) p-value < 0.01. (XLSX 9 kb)

Additional file 2:

Correlation between RAGE, AGE and PFT. AGE: advanced glycation end-product, cHP: chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, DLCO: diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide, fNSIP: fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia, FVC: forced vital capacity, IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, r: correlation coefficient, R2: coefficient of determination, sRAGE: soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products, TLC: Total lung capacity. (*) p-value < 0.05, (**) p-value < 0.01. (XLSX 9 kb)

Additional file 3:

AGEs-sRAGE correlation in IPF patients during follow-up. IPF patients with a decline of AGEs in serum showed an increase of soluble fragment of the receptor in blood. (PDF 109 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Machahua, C., Montes-Worboys, A., Planas-Cerezales, L. et al. Serum AGE/RAGEs as potential biomarker in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 19, 215 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0924-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0924-7