Abstract

Background

Leptospiral glycolipoprotein (GLP) is a potent and specific Na/K-ATPase inhibitor. Severe pulmonary form of leptospirosis is characterized by edema, inflammation and intra-alveolar hemorrhage having a dismal prognosis. Resolution of edema and inflammation determines the outcome of lung injury. Na/K-ATPase activity is responsible for edema clearance. This enzyme works as a cell receptor that triggers activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) intracellular signaling pathway. Therefore, injection of GLP into lungs induces injury by triggering inflammation.

Methods

We injected GLP and ouabain, into mice lungs and compared their effects. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected for cell and lipid body counting and measurement of protein and lipid mediators (PGE2 and LTB4). The levels of the IL-6, TNFα, IL-1B and MIP-1α were also quantified. Lung images illustrate the injury and whole-body plethysmography was performed to assay lung function. We used Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) knockout mice to evaluate leptospiral GLP-induced lung injury. Na/K-ATPase activity was determined in lung cells by nonradioactive rubidium incorporation. We analyzed MAPK p38 activation in lung and in epithelial and endothelial cells.

Results

Leptospiral GLP and ouabain induced lung edema, cell migration and activation, production of lipid mediators and cytokines and hemorrhage. They induced lung function alterations and inhibited rubidium incorporation. Using TLR4 knockout mice, we showed that the GLP action was not dependent on TLR4 activation. GLP activated of p38 and enhanced cytokine production in cell cultures which was reversed by a selective p38 inhibitor.

Conclusions

GLP and ouabain induced lung injury, as evidenced by increased lung inflammation and hemorrhage. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing GLP induces lung injury. GLP and ouabain are Na/K-ATPase targets, triggering intracellular signaling pathways. We showed p38 activation by GLP-induced lung injury, which was may be linked to Na/K-ATPase inhibition. Lung inflammation induced by GLP was not dependent on TLR4 activation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Leptospirosis is a worldwide zoonosis caused by pathogenic spirochetes of the genus Leptospira. This disease affects both animals and humans and has veterinary, economic and medical relevance [1]. In tropical countries, epidemic outbreaks occur in the rainy season and after floods [2]. Infection commonly occurs after contact with contaminated soil and water. An intact keratinocyte layer is a barrier against leptospiras [3], but water sprays can facilitate bacterial entry [4]. During the acute phase of the disease, leptospiras are found in the liver and kidneys [5]. Pulmonary involvement in leptospirosis (Weil’s disease) has been reported over the last 20 years and is related to the severity and mortality of the disease [6],[7].

Bacterial recognition by a host during leptospirosis is still not completely understood, but the presence of leptospira may be sensed through Toll-like receptors (TLR4 and TLR2) [8],[9]. The leptospiral lipopolysaccharide (LPS) differs from those found in other Gram(-) bacteria. In this regard, lipid A, the active component of leptospiral LPS, is structurally and functionally different from that of E. coli[10]. The recognition of L. interrogans LPS requires CD14 and TLR2, but L. interrogans LPS is incapable of inducing intracellular signaling through TLR4 activation [9]. A key protein of the outer leptospiral membrane, the lipoprotein LipL32, is produced during leptospirosis [11]. This protein is highly conserved and found exclusively in pathogenic leptospiras [12]. LipL32 has been shown to activate TLR2 [9] in a Ca2+-binding cluster-dependent manner [13].

Another leptospiral component with cytotoxic activity is the glycolipoprotein fraction GLP [14]. The observation that GLP causes a decrease in renal water absorption provides new evidence that this component is an important contributor to the virulence of pathogenic Leptospira[15]. Due to their peculiar metabolism, leptospiras are able to store fatty acids [14]. Some of them (e.g., palmitovaccenic and linoleic acids) are associated with GLP [14], while others (e.g., hydroxylauric and palmitic acids) are associated with LPS and lipopolysaccharide-like substance (LLS) [16]. Oleic acid is associated with both LPS and GLP.

We have proposed that nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) produce toxic effects and are involved in multi-organ failure that is characteristic of Weil’s disease [17]. Supporting those findings, we have demonstrated increased molar ratios of serum NEFA; in particular, the linoleic and oleic acids/albumin molar ratios are increased in severe forms of leptospiral infection [17].

The resolution of pulmonary edema and lung inflammation are important determinants of the outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [18]. Resolution of alveolar edema is dependent on the transfer of salt and water across the alveolar epithelium through apically located sodium channels (ENaC) followed by extrusion to the lung interstitium via the basolaterally located Na/K-ATPase [19].

GLP inhibits Na/K-ATPase [20], and oleic acid has been shown to inhibit Na/K-ATPase in the lung in a rabbit model, resulting in a complete block of active sodium transport and enhancement of endothelial permeability [21]. Cardiac glycosides are a large family of clinically relevant, specific Na/K-ATPase inhibitors that have been classically used to treat heart failure [22]. In addition to their classical effects, ouabain induces internalization and lysosomal degradation of Na/K-ATPase [23], triggering intracellular pathways (including MAPK activation) [24] and inducing lung injury [25].

Increased cytokine production correlates with a lethal outcome in leptospirosis patients [26]. IL-6 release seems to play a key role in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), although its detailed mechanism of action remains unclear [27]. In addition, the infection of guinea pigs with L. interrogans serovar Icteroheamorrhagiae leads to increased IL-6 and TNFα mRNA levels in the lung [28]. IL-1β and IL-18 are produced as cytosolic precursors that require secondary proteolytic cleavage, which is dependent on inflammasome activation [29]. The inflammasome consists of several proteins. One of these, NLRP3, is involved in the recognition of bacterial RNA, ATP, uric acid and low intracellular potassium concentrations (which is a consequence of the inhibition of Na/K-ATPase) [30].

In Brazil, the clinical patterns of leptospirosis have changed, and severe cases with pulmonary involvement have been detected [31],[32]. Nevertheless, the associated pulmonary distress is not due to extensive bacterial lung colonization [33],[34]. Leptospiral components, including GLP, can induce lung injury following their release by bacteria killed during the immune response, as they can ultimately reach the lung.

Oleic acid, an inhibitor of Na/K-ATPase activity [20],[21], has been used experimentally to induce lung injury in mice [35]. Intravenously and intratracheally injected oleic acid targets lung Na/K-ATPase in vivo[25],[36]. In this respect, GLP is a much more specific Na/K-ATPase inhibitor than only oleic acid [20]. Oleic acid-induced lung injury and IL-6 production in the murine lung occur through ERK1/2 activation [36], and as we have shown, Na/K-ATPase is a target for GLP and fatty acids and plays an important role in leptospirosis physiopathology [37]. GLP fatty acid components, including oleic acid, are responsible for the biological effects of GLP [20].

In this study, we compared two specific Na/K-ATPase inhibitors (GLP and ouabain), which were administered through the intra-tracheal route, for their ability to induce lung edema, cell migration and activation, and the production of lipid mediators and cytokines in different mouse strains. Because oleic acid triggers lung injury through MAPK ERK [38], we also investigated if GLP can activate the MAPK pathway.

Methods

Animals

We used male mice (25 – 30 g) of the following strains: Swiss Webster (SW) and C57Bl/10 (from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation breeding unit, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and C57Bl/10ScCr (kindly provided by the Federal Fluminense University breeding unit, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). The animals were housed at 22°C with a 12-h light/dark cycle and free access to food and water.

Ethical statement

The Animal Welfare Committee of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation approved all the experiments under license numbers 002-08 and LW36/10 (CEUA/FIOCRUZ).

Reagents

Ouabain (purity > 99%) and E. coli LPS were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. All other reagents were of the highest purity grade.

Preparation of the GLP fraction

GLP was prepared from Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni strain Fiocruz L1-130 as previously described [14]. L. interrogans was grown at 28°C in EMJH medium (Bio-Rad) without agitation. At the end of the exponential phase, the bacteria were pelleted at 9000 × g in an endotoxin-free, 50-mL polypropylene tube and frozen at -80°C. The pellet was resuspended in endotoxin-free 0.01 M Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), lysed at 4-8°C for 48 h by agitating with glass beads and then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 18°C. The supernatant was treated with RNase and DNase (50 μg/mL each for 3 h at 37°C) and then dialyzed for 24 h at 4°C against 0.1 M Tris/HCl buffer (pH 7.4). After acidification to pH 3.7 with 1 M acetic acid at 4°C, GLP was sedimented by ultracentrifugation (4000 × g, 30 min, 4°C), washed twice with 0.1 M acetic acid and lyophilized. The lyophilized GLP was kept frozen at -20°C. At the time of usage, the lyophilized powder was suspended in sterile saline, and 50 μL of the solution, containing 12 μg of GLP protein, was injected into each animal. The Bradford method was used to determine the protein concentration of the GLP preparation [39]. The preparation (6 μg of GLP protein) retained its inhibitory properties, inhibiting approximately 50% the activity of a standard Na/K-ATPase preparation according to our previous work [20]. This means that the GLP inhibitory properties were tested in vitro prior to its injection into mice lung.

Intra-tracheal administration of GLP, ouabain or Gram(-) LPS

Each mouse was anesthetized with isoflurane, and an incision was made above the thyroid region to expose the trachea. Then, using a syringe, 50 μL of the following doses were instilled into the tracheas of different groups of mice: ouabain (0.075 μmol/animal), GLP (12 μg of GLP protein/animal), Gram(-) E. coli LPS (500 ng/animal) and, for the control groups, 50 μL of sterile saline. Ouabain was injected into SW mice, E. coli LPS was injected into C57Bl/10 and C57Bl/10ScCr, and GLP was injected into all mouse strains.

Total and differential cell analysis and total protein quantification in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF)

After euthanizing the mice in a CO2 chamber, the tracheas were isolated by blunt dissection, and three 1.0-mL aliquots of PBS were sequentially instilled into each animal through a small-caliber tube inserted into the airway. After gentle aspiration, 1 mL of fluid was recovered per instillation/aspiration cycle. The aliquots were pooled, for a total of approximately 3 mL of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid per mouse. Total leukocyte counts were performed using microscopy and Neubauer chambers after diluting the BALF samples in Türk solution (2% acetic acid). The differential leukocyte counts of cytocentrifuged smears stained by the May-Grunwald-Giemsa method were determined. The total protein in the BALF supernatants was determined using the Micron BCA Kit method (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Lipid body staining and quantification

While still moist, the leukocytes on the CytoSpin slides were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hank’s buffered salt solution (HBSS; pH 7.4) and stained with 1.5% OsO4 [40]. The lipid bodies in 50 consecutively scanned leukocytes were enumerated by microscopy.

Cytokine/chemokine measurement assays

The IL-6, CCL3/MIP-1α, TNFα and IL1β concentrations in the cell free-BALF supernatants were measured using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Duo Set, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA).

PGE2 and LTB4 assays

The concentrations of LTB4 and PGE2 in the BALF supernatants were assayed using enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Measurement of airway function

The airway function in individual unrestrained animals was evaluated 24 h after challenge by barometric plethysmography using a whole body plethysmograph (WBP, Buxco, Troy, NY) as previously described [41].

Morphological studies

Twenty-four hours after challenge with leptospiral GLP, E. coli LPS, ouabain or saline, the animals were euthanized in a CO2 chamber, and the lungs were removed. For microscopic studies, the lungs were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Isolation of human endothelial cells

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were isolated as previously described [42],[43] and grown in 199 medium (M-199, Sigma) supplemented with 15 mM HEPES, antibiotics (100 U penicillin/mL, 100 mg streptomycin/mL), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 20% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS, Cultilab complete medium). The cells were used at the first or second passages only, and subcultures were obtained by treatment of confluent cultures with 0.025% (w/v) trypsin/0.2% (w/v) EDTA in PBS. Cell viability was assessed with Trypan blue, and it remained above 95%.

Epithelial cell culture experiments

A549 lung epithelial cells were kindly provided by Dr. Cristina Plotkowski (from the Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil) and were maintained in complete DMEM/F12 (Hyclone) medium (containing 2% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin, and 100 UI/mL streptomycin). A day before the experiment, the cells were treated with trypsin (0.025%), centrifuged at 4°C and 400 × g for 10 min, resuspended in the complete medium, and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 in 24-well plates (300,000 cells per well). The cells were then washed with PBS 30 min after the stimulus, lysed with lysis buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton) containing protease inhibitors (Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets from Roche), and stored at -20°C.

Lung tissue experiments

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and then perfused with 20 mL of 20 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) pH 7.4 through the right cardiac ventricle. Then, the lung tissues were cut into small pieces and homogenized at 4°C in a homogenizer using the lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors.

Evaluation of p38 activation in cultured cells and lung tissues

Cell suspensions and lung lysates in the electrophoresis sample buffer were heated at 100°C for 5 min and run in 10% polyacrylamide gels (PAGE-SDS). After transfer of the proteins to nitrocellulose membranes at 15 V for 60 min (Biorad semidry system), the membranes were incubated with a blocking solution followed by incubation with a monoclonal antibody against phosphorylated p38 (Cell Signaling; 1:1000 dilution) and then with a peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Pierce; 1:10,000). Detection was performed by utilizing the “Super Signal Chemiluminescence” kit (Pierce) and then exposing the membrane to an autoradiograph film (Kodak MR Biomax). Membranes containing proteins were stripped, blocked again, and incubated with monoclonal antibodies to total p38 (Cell Signaling; 1:1000) or glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) followed by treatment with an anti-mouse antibody conjugated to peroxidase. After digitalized and analysis by size and intensity using the Image Master 2D Elite 4.01 equipment, the bands were compared to those of the controls and normalized against total p38 or GAPDH. The expression results are in folds over the controls.

Treatment with a MAPK p38 phosphorylation inhibitor

The p38 phosphorylation selective inhibitor SB203580 (4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-5-(4- pyridyl)imidazole) at a concentration of 10 μM was incubated with A549 cells 30 min before GLP stimuli. The SB203580 was previously dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) and diluted with PBS when used.

Na/K ATPase assay in HUVECs based on Rb+incorporation

E.coli LPS, ouabain and leptospiral GLP were diluted in KCl free-Hank’s solution containing non-radioactive Rb+ and incubated with cells for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. The culture was washed with cold PBS and cells were lysed with 600 μL of SDS 0.25%. Samples were centrifuged 10000 × g[44] and Rb+ was quantified by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) using an Ultima 2 apparatus with Mira Mist Nebulizer and spray chamber (Jobin Yvon, Longjumeau, France). A rubidium nitrate standard (Ultra Scientific, EUA) was used to construct the calibration curve. Results were expressed in μmol of Rb+ incorporated per 30 min per 3 × 105 cells.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Newman-Keuls-Student posttest to compare all columns. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Results

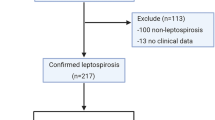

GLP (12 μg of protein/animal) and ouabain (0.075 μmol/animal) injected intratracheally induced cell accumulation in BALF, as demonstrated by the increased number of neutrophils (Figure 1A and B). The total protein concentration of BALF supernatants was also increased after GLP administration (Figure 1C), indicating increased vascular permeability and edema formation.

Cell migration and protein extravasation in BALF of SW mice 24 h after intra-tracheal challenge with ouabain (0.075 μmol/animal) or GLP (12 μg of GLP protein/animal). (A) Total cells, (B) neutrophils, and (C) total protein in BALF supernatant. Controls received 50 μL of sterile saline. Cell migration and edema formation in lungs of C57BL/10 and C57BL/10ScCr (TLR4-deficient) mice 24 h after intra-tracheal challenge with LPS (500 ng/animal) or GLP (12 μg of GLP protein/animal). Controls received 50 μL of sterile saline. Controls (white bars), LPS-treated (gray bars), and GLP-treated (black bars). (D) Total cells, (E) neutrophils and (F) total protein in BALF supernatants. The results are the means ± SEM of at least 8 animals. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group; #P < 0.05 when both strains were compared.

As the activation of TLR4 protects mice against lethal leptospiral infection [45], we compared the effects of leptospiral GLP and E. coli LPS challenges in C57BL10/ScCr mice, which possess a null mutation for TLR4 and are therefore resistant to high doses of LPS [46]. The wild-type controls showed a typical response to LPS, with increased cell migration and higher total protein content in BALF, while, as expected, the C57BL10/ScCr mice did not respond to LPS. GLP and ouabain not only induced cell accumulation in BALF but also augmented the total protein in both C57BL10/ScCr and wild type control animals (Figure 1D, E and F), thus excluding the possibility of LPS contamination of our GLP preparation.

BALF leukocytes showed signs of activation because lipid body numbers were markedly augmented 24 h after GLP administration (Figure 2A). The concentrations of the lipid mediators PGE2 (Figure 2B) and LTB4 (Figure 2C) were significantly increased in the BALF supernatants after GLP or ouabain challenge. In addition to inflammatory lipid mediators, we also observed increased cytokine concentrations (IL-6, IL-1β, MIP-1α and TNFα) in BALF supernatants 24 h after administration of GLP or ouabain (Figure 3A, B, C and D, respectively).

Lipis body formation and lipid mediators production in BALF of SW mice 24 h after intra-tracheal challenge with ouabain (0.075 μmol/animal) or GLP (12 μg of GLP protein/animal). Lipid body numbers (A), PGE2 concentrations (B) and LTB4 concentrations (C) in BALF of SW mice 24 h after intra-tracheal challenge with ouabain (0.075 μmol/animal) or GLP (12 μg of GLP protein/animal). Controls received 50 μL of sterile saline. Number of leukocyte lipid bodies and the production of LTB4 and IL-1β in BALF supernatants of C57BL/10 and C57BL/10ScCr mice 24 h after intra-tracheal challenge with LPS (500 ng/animal) or GLP (12 μg of GLP protein/animal). Controls received 50 μL of sterile saline. Controls (white bars), LPS-treated (gray bars), and GLP-treated (black bars). (D) Lipid bodies, (E) LTB4 and (F) IL-1β. The results are the means ± SEM of 6 to 8 animals per group. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group; #P < 0.05 when both strains were compared.

Production of inflammatory cytokines in BALF supernatants of SW mice 24 h after intra-tracheal challenge with ouabain (0.075 μmol/animal) or GLP (12 μg of GLP protein/animal). (A) IL-6, (B) IL-1β, (C) MIP-1α, and (D) TNF-α. Controls received 50 μL of sterile saline. The results are the means ± SEM of at least 8 animals.

As TLR4 is an important leptospiral sensor, we further investigated other inflammatory parameters, such as lipid body formation and the production of LTB4 and IL-1β, in TLR4-deficient mice. GLP-induced lipid body formation was similar in wild-type and C57BL10/ScCr mice (Figure 1D). The same pattern was observed for the IL-1β and LTB4 levels in BALF supernatants (Figure 1B and C). Again, as expected, LPS did not induce lipid body formation or the production of IL-1β and LTB4 in C57BL10/ScCr mice.

The lung is a key target in leptospirosis; ARDS patients frequently present hemorrhage, which can be fatal [32], and leptospirosis-susceptible animals present lung hemorrhage [47]. Macroscopic lung evaluation (Figure 4B and C) clearly showed intense hemorrhage 24 h after GLP or ouabain administration compared to controls (Figure 4A). Microscopic analyses of the lungs confirmed intense alveolar hemorrhage in GLP- (Figure 4E), ouabain- (Figure 4F) and GLP plus ouabain-treated animals (Figure 4G) compared to control animals (Figure 4D). All stimuli induced structural damage in the lung, with inflammatory cell infiltration and focused hemorrhage, characterizing a direct lung insult. Ouabain induced a less-intense hemorrhage, and animals injected with GLP plus ouabain presented high mortality rates immediately after injection (data not shown). Functional analysis by lung plethysmography (bar graph, Figure 4H) revealed altered pulmonary function after challenge with ouabain or GLP.

Representative macro and microphotographs of SW mouse lungs 24 h after intra-tracheal challenge with ouabain (0.075 μmol/animal), GLP (12 μg of GLP protein/animal) or ouabain plus GLP. Macroscopic photos of mouse lungs challenged with (A) sterile saline (control), (B) ouabain or (C) GLP. Photomicrographs of the same lungs, showing intact alveolar structures in the control group (D) and hemorrhagic sites in the lungs from mice challenged with leptospiral GLP (E), ouabain (F) or GLP plus ouabain (GLP + ouabain) (G). Plethysmographic analysis of lung function (H), where the enhanced pause (Penh) was used to represent airway resistance. The plethysmographic results are represented as the mean ± SEM of 7 to 15 animals. *P < 0.05.

Na/K-ATPase is a signal transducer that interacts with different signaling proteins to form a complex called the signalosome [48]. One pathway involves activation of the Ras-Raf-MAPK cascade [49], which ultimately activates ERK, c-jun kinase (JNK) and p38. In this regard, we evaluated p38 activation in the lung, lung epithelial cells and human endothelial cells. GLP induced p38 activation, increasing its phosphorylation in lung (Figure 5A), which was different from the effect of oleic acid. Oleic acid activates the ERK pathway [38]. GLP induced p38 phosphorylation (6.7×) and the production of the IL-8 chemokine in human endothelial cells (Figure 6A and B) as well as lung inflammation, demonstrating that the intra-tracheal administration of leptospiral GLP causes lung injury. Based on our previous in vitro report showing GLP as a Na/K-ATPase inhibitor [20],[50] and the results of the present work, we suggest that this enzyme is a target for GLP in vivo.

GLP-induced p38 phosphorylation in the lung tissue. Lungs were removed from SW animals 4 h after the GLP challenge. The graphs represent densitometry analysis of the phosphorylated p38 and total p38 bands (A), as detailed in the Methods section. The bars represent the medians of the two animals. Oleic acid, a constituent of GLP did not activate p38.

GLP-induced p38 phosphorylation and IL-8 production in HUVECs. Cultured cell lysates were prepared after incubation with GLP for 30 min or for up to 24 h to measure the IL-8 level (B) the in the supernatant. The graphs represent densitometry analysis of phosphorylated p38 and total p38 bands (A), as detailed in the Methods section.

Finally, GLP induced p38 phosphorylation and IL-6 production in lung epithelial cells, and this effect was reversed by the selective p38 inhibitor SB203580 (Figure 7A), which addresses a key role of p38 in GLP-induced lung inflammation.

Blocking p38 activation by treatment with the selective inhibitor SB203580 decreases GLP-induced p38 phosphorylation and IL-6 production. Cultured cell lysates were prepared after incubation with SB203580 and GLP for 30 min, as detailed in the Methods section. Cultured cell were incubated with GLP for up to 24 h to measure the IL-6 level in the supernatant (A). *P < 0.05 compared to the control group; #P < 0.05 compared to the GLP group.

We showed that GLP inhibited purified Na/KATPase in vitro[20]. During leptospirosis, the immune response kills the bacteria, releasing GLP into the bloodstream, where it reaches the lung capillary net. In the present work, ouabain and GLP inhibited Na/K-ATPase in endothelial cells (Figure 8), whereas E. coli LPS had no effect.

Inhibition of Rb+incorporation into HUVECs by E. coli LPS, ouabain or leptospiral GLP. The control group was incubated solely with KCl-free Hank’s solution containing non-radioactive Rb+. We compared the effects of ouabain (100, 250 and 500 nM), LPS 1 μg/mL and GLP (6 and 12 μg of GLP protein) in the experimental groups. Rb+ incorporation in cell cultures after 30 min of treatment was measured by ICP-OES. The results are expressed in μmol Rb+ incorporated per hour per 3 × 105 cells. Ouabain-sensitive inhibition of Na/K-ATPase is shown as a difference between Rb+ incorporation in the absence and in the presence of ouabain. Ouabain-insensitive Rb+ incorporation represents the amount of Rb+ entering cells through potassium channels and through passive diffusion. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group.

Discussion

We used a murine model to study the effects of leptospiral GLP on inflammation [51]. GLP decreased the mRNA levels of Na/K-ATPase β1 in vitro[52]. These results revealed that Na/K-ATPase inhibition in alveolar cells is involved in lung edema formation.

Neutrophils are the main cells that migrate to the lung during ARDS. When activated, they release an arsenal of potent molecules that contribute to tissue damage and inflammation [53]. Our data showed neutrophil infiltration after GLP or ouabain injection. Cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukins (mainly IL-1β and IL-6) contribute to the development of ARDS by increasing vascular permeability and organ dysfunction [53]. GLP has also been shown to activate blood mononuclear cells, leading to augmented TNF-α and IL-6 production [54]. Ouabain is known to affect the immune system by modulating cytokine production, and its administration has been shown to induce IL-1 and TNF-α production by mononuclear cells [55]. Our results showed increased lung levels of IL-6, IL-1β, MIP-1α and TNFα in BALF supernatants in GLP- or ouabain-challenged animals. To our knowledge, this is the first report of lung injury induced by intra-tracheal ouabain injection. The chemokine MIP-1α, a chemotactic factor for monocytes [56], was also increased in our model. Therefore, challenge with GLP or ouabain induced the main inflammatory mediators involved in ARDS.

The levels of LTB4, a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils [57], increased after GLP or ouabain challenge; therefore, LTB4 might be involved in neutrophil migration. The production of PGE2 was also elevated after either type of challenge. Recent work has shown that ouabain-induced PGE2 production in the murine lung is dependent on cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) activation [58]. In this regard, some evidence has suggested that the COX-2/PGE2 pathway plays an important role in augmenting the inflammatory immune response during ARDS, as the inhibition of PGE2 synthesis prevents edema formation, neutrophil infiltration, pro-inflammatory cytokine production and the expression of adhesion molecules, thereby restoring lung morphology and increasing survival during poly-microbial sepsis [59]. The GLP-induced production of lipid mediators is most likely associated with increased number of lipid bodies, which serve as privileged sites for lipid mediator production [60],[61].

Hemorrhage can lead to high mortality rates [62]. Lung hemorrhage can be present in severe leptospirosis [1],[6],[63],[64] but is less frequent in other ARDS etiologies. This hemorrhagic syndrome has been described in leptospirosis patients in China, Korea, Brazil and Nicaragua [65],[66]. Animals with leptospirosis infection also display lung hemorrhage [47],[67]. We have previously shown that ouabain induces hemorrhagic foci in the lung following local administration [68] and that the hemorrhage is less extensive compared to GLP. GLP induced both lung inflammation and hemorrhage, which contribute to decreased lung function. Lung hemorrhage may have influenced the quantities of cytokines and proteins in the BALF because serum may have flooded the alveoli, increasing the albumin content; therefore, systemic cytokines may have contributed to the total cytokine levels measured in the BALF.

We cannot eliminate the possible presence of a contaminating molecule in our GLP preparation. Nevertheless, when a mouse strain carrying a null TLR4 mutation was compared with the corresponding wild-type strain, we found that GLP did not act through TLR4 activation, which indicates that our GLP preparation was free of Gram(-) LPS. Accordingly, evidence for renal colonization by leptospira inducing a mild renal fibrosis in mice through TLR- and NLR-independent pathways would explain the TLR4-independent effect of GLP [69]. Leptospiral GLP activates the NLRP3 inflammasome protein by down regulating the Na/K-pump [52]. Inflammasome activation is an important step in IL-1β release, and in our study, the IL-1β production in the lung was similar to that induced by GLP and ouabain. Therefore, inflammasome activation may play an important role in the inflammatory events related to leptospirosis.

The signal transduction capacity of Na/K-ATPase occurs through properties different from its function as an ion pump and does not depend on changes in the intracellular Na+ and K+ concentrations [70]. We showed a new GLP mechanism of action through the activation of p38, whereby Na/K-ATPase activity and lung inflammation triggered by GLP are linked. Therefore, we suggest another mechanism of Na/K-ATPase in lung inflammation beyond its key role in edema formation and/or clearance, strengthening the idea that Na/K-ATPase may be involved in inflammation [71].

Na/K-ATPase has signaling properties [72] that promote intracellular activation [73]. Furthermore, the GLP components oleic acid and ouabain target the Na/K-ATPase in the lung when injected intravenously and cause lung injury [25]. Both GLP and ouabain injected directly into the lung induced similar levels of lung inflammation in SW mice. Furthermore, GLP inhibited Na/K-ATPase in HUVECs and induced inflammatory mediators in both endothelial and lung epithelial cells. Considering Na/K-ATPase as the sole receptor described for ouabain to date, we suggest that GLP may also affect the Na/K-ATPase-dependent activation of signaling cascades.

Conclusions

GLP and ouabain inhibited Na/K-ATPase in endothelial cells and induced lung injury, as shown by increases in lung inflammation markers and hemorrhage, which also occurs in some leptospirosis patients. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing that GLP induces lung injury. The lung inflammation induced by GLP in our in vivo mouse model was not dependent on the activation of TLR4. Although inflammasome activation by low concentrations of intracellular K+ surely plays an important role, we showed that GLP activates the p38 pathway, possibly through Na/K-ATPase, resulting in inflammation.

Abbreviations

- GLP:

-

Glycolipoprotein fraction

- Na/K-ATPase:

-

Enzyme sodium potassium ATPase

- TLR:

-

Toll-like receptor

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NEFA:

-

Nonesterified fatty acids

- LLS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide-like substance

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- LipL:

-

Leptospiral outer membrane lipoprotein

- BALF:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- LTB4:

-

Leukotriene B4

- PGE2:

-

Prostaglandin E2

- NLRP3:

-

NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3

- ICP-OES:

-

Inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry

References

Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, Matthias MA, Diaz MM, Lovett MA, Levett PN, Gilman RH, Willig MR, Gotuzzo E, Vinetz JM: Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003, 3: 757-771. 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00830-2.

Reis RB, Ribeiro GS, Felzemburgh RD, Santana FS, Mohr S, Melendez AX, Queiroz A, Santos AC, Ravines RR, Tassinari WS, Carvalh MS, Reis MG, Ko AI: Impact of environment and social gradient on leptospira infection in urban slums. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008, 2: e228-10.1371/journal.pntd.0000228.

Zhang Y, Lou XL, Yang HL, Guo XK, Zhang XY, He P, Jiang XC: Establishment of a leptospirosis model in guinea pigs using an epicutaneous inoculations route. BMC Infect Dis. 2012, 12: 20-10.1186/1471-2334-12-20.

Goris MG, Boer KR, Duarte TA, Kliffen SJ, Hartskeerl RA: Human leptospirosis trends, the Netherlands, 1925-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013, 19: 371-378. 10.3201/eid1903.111260.

Athanazio DA, Silva EF, Santos CS, Rocha GM, Vannier-Santos MA, McBride AJ, Ko AI, Reis MG: Rattus norvegicus as a model for persistent renal colonization by pathogenic Leptospira interrogans. Acta Trop. 2008, 105: 176-180. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.10.012.

Ranawaka N, Jeevagan V, Karunanayake P, Jayasinghe S: Pancreatitis and myocarditis followed by pulmonary hemorrhage, a rare presentation of leptospirosis- a case report and literature survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2013, 13: 38-10.1186/1471-2334-13-38.

Del Carlo BF, Ctenas B, da Silva LF, Nicodemo AC, Saldiva PH, Dolhnikoff M, Mauad T: Immune receptors and adhesion molecules in human pulmonary leptospirosis. Hum Pathol. 2012, 43: 1601-1610. 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.11.017.

Nahori MA, Fournie-Amazouz E, Que-Gewirth NS, Balloy V, Chignard M, Raetz CR, Saint Girons I, Werts C: Differential TLR recognition of leptospiral lipid A and lipopolysaccharide in murine and human cells. J Immunol. 2005, 175: 6022-6031. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6022.

Werts C, Tapping RI, Mathison JC, Chuang TH, Kravchenko V, Saint Girons I, Haake DA, Godowski PJ, Hayashi F, Ozinsky A, Underhill DM, Kirschning CJ, Wagner H, Aderem A, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ: Leptospiral lipopolysaccharide activates cells through a TLR2-dependent mechanism. Nat Immunol. 2001, 2: 346-352. 10.1038/86354.

Que-Gewirth NL, Ribeiro AA, Kalb SR, Cotter RJ, Bulach DM, Adler B, Girons IS, Werts C, Raetz CR: A methylated phosphate group and four amide-linked acyl chains in leptospira interrogans lipid A. The membrane anchor of an unusual lipopolysaccharide that activates TLR2. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279: 25420-25429. 10.1074/jbc.M400598200.

Hsu SH, Lo YY, Tung JY, Ko YC, Sun YJ, Hung CC, Yang CW, Tseng FG, Fu CC, Pan RL: Leptospiral outer membrane lipoprotein LipL32 binding on toll-like receptor 2 of renal cells as determined with an atomic force microscope. Biochemistry. 2010, 49: 5408-5417. 10.1021/bi100058w.

Murray GL: The lipoprotein LipL32, an enigma of leptospiral biology. Vet Microbiol. 2013, 162: 305-314. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.11.005.

Lo YY, Hsu SH, Ko YC, Hung CC, Chang MY, Hsu HH, Pan MJ, Chen YW, Lee CH, Tseng FG, Sun YJ, Yang CW, Pan RL: Essential Calcium-binding Cluster of Leptospira LipL32 Protein for Inflammatory Responses through the Toll-like Receptor 2 Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2013, 288: 12335-12344. 10.1074/jbc.M112.418699.

Vinh T, Adler B, Faine S: Glycolipoprotein cytotoxin from Leptospira interrogans serovar copenhageni. J Gen Microbiol. 1986, 132: 111-123.

Cesar KR, Romero EC, de Braganca AC, Blanco RM, Abreu PA, Magaldi AJ: Renal involvement in leptospirosis: the effect of glycolipoprotein on renal water absorption. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e37625-10.1371/journal.pone.0037625.

Vinh T, Adler B, Faine S: Ultrastructure and chemical composition of lipopolysaccharide extracted from Leptospira interrogans serovar copenhageni. J Gen Microbiol. 1986, 132: 103-109.

Burth P, Younes-Ibrahim M, Santos MC, Castro-Faria Neto HC, de Castro Faria MV: Role of nonesterified unsaturated fatty acids in the pathophysiological processes of leptospiral infection. J Infect Dis. 2005, 191: 51-57. 10.1086/426455.

Matthay MA, Folkesson HG, Clerici C: Lung epithelial fluid transport and the resolution of pulmonary edema. Physiol Rev. 2002, 82: 569-600.

Sznajder JI, Factor P, Ingbar DH: Invited review: lung edema clearance: role of Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase. J Appl Physiol. 2002, 93: 1860-1866.

Burth P, Younes-Ibrahim M, Goncalez FH, Costa ER, Faria MV: Purification and characterization of a Na+, K + ATPase inhibitor found in an endotoxin of Leptospira interrogans. Infect Immun. 1997, 65: 1557-1560.

Vadasz I, Morty RE, Kohstall MG, Olschewski A, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Ghofrani HA: Oleic acid inhibits alveolar fluid reabsorption: a role in acute respiratory distress syndrome?. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005, 171: 469-479.

Schoner W, Scheiner-Bobis G: Endogenous and exogenous cardiac glycosides and their mechanisms of action. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2007, 7: 173-189. 10.2165/00129784-200707030-00004.

Cherniavsky-Lev M, Golani O, Karlish SJ, Garty H: Ouabain-induced internalization and lysosomal degradation of the Na+/K+ ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2013, 289 (2): 1049-1059. 10.1074/jbc.M113.517003.

Xie Z, Askari A: Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase as a signal transducer. Eur J Biochem. 2002, 269: 2434-2439. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02910.x.

Goncalves-de-Albuquerque CF, Burth P, Silva AR, de Moraes IM, de Jesus Oliveira FM, Santelli RE, Freire AS, Bozza PT, Younes-Ibrahim M, de Castro-Faria-Neto HC, de Castro-Faria MV: Oleic acid inhibits lung Na/K-ATPase in mice and induces injury with lipid body formation in leukocytes and eicosanoid production. J Inflamm (Lond). 2013, 10: 34-10.1186/1476-9255-10-34.

Wagenaar JF, Goris MG, Gasem MH, Isbandrio B, Moalli F, Mantovani A, Boer KR, Hartskeerl RA, Garlanda C, van Gorp EC: Long pentraxin PTX3 is associated with mortality and disease severity in severe Leptospirosis. J Infect. 2009, 58: 425-432. 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.04.004.

Imai Y, Kuba K, Neely GG, Yaghubian-Malhami R, Perkmann T, van Loo G, Ermolaeva M, Veldhuizen R, Leung YH, Wang H, Liu H, Sun Y, Pasparakis M, Kopf M, Mech C, Bavari S, Peiris JS, Slutsky AS, Akira S, Hultqvist M, Holmdahl R, Nicholls J, Jiang C, Binder CJ, Penninger JM: Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell. 2008, 133: 235-249. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.043.

Marinho M, Oliveira-Junior IS, Monteiro CM, Perri SH, Salomao R: Pulmonary disease in hamsters infected with Leptospira interrogans: histopathologic findings and cytokine mRNA expressions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 80: 832-836.

Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J: The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002, 10: 417-426. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3.

Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O: Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006, 124: 783-801. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015.

Ko AI, Galvao Reis M, Ribeiro Dourado CM, Johnson WD, Riley LW: Urban epidemic of severe leptospirosis in Brazil. Salvador Leptospirosis Study Group. Lancet. 1999, 354: 820-825. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80012-9.

Gouveia EL, Metcalfe J, de Carvalho AL, Aires TS, Villasboas-Bisneto JC, Queirroz A, Santos AC, Salgado K, Reis MG, Ko AI: Leptospirosis-associated severe pulmonary hemorrhagic syndrome, Salvador, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008, 14: 505-508. 10.3201/eid1403.071064.

Zaltzman M, Kallenbach JM, Goss GD, Lewis M, Zwi S, Gear JH: Adult respiratory distress syndrome in Leptospira canicola infection. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981, 283: 519-520. 10.1136/bmj.283.6290.519.

Pereira MM, Andrade J, Marchevsky RS, Ribeiro dos Santos R: Morphological characterization of lung and kidney lesions in C3H/HeJ mice infected with Leptospira interrogans serovar icterohaemorrhagiae: defect of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells are prognosticators of the disease progression. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1998, 50: 191-198. 10.1016/S0940-2993(98)80083-3.

Goncalves de Albuquerque CF, Burth P, Younes Ibrahim M, Garcia DG, Bozza PT, Castro Faria Neto HC, Castro Faria MV: Reduced plasma nonesterified fatty acid levels and the advent of an acute lung injury in mice after intravenous or enteral oleic acid administration. Mediators Inflamm. 2012, 2012: 601032-

Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque C, Silva A, Burth P, Moraes I, Oliveira F, Younes Ibrahim M, Santos M, D’Ávila H, Bozza P, Castro Faria Neto H, Castro Faria M: Oleic acid induces lung injury in mice through activation of the ERK pathway. Mediators Inflamm. 2012, 2012: 11-

Goncalves-de-Albuquerque CF, Burth P, Silva AR, Younes-Ibrahim M, Castro-Faria-Neto HC, Castro-Faria MV: Leptospira and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2012, 2012: 317950-

Goncalves-de-Albuquerque CF, Silva AR, Burth P, de Moraes IM, Oliveira FM, Younes-Ibrahim M, dos Santos Mda C, D’Avila H, Bozza PT, Faria Neto HC, Faria MV: Oleic acid induces lung injury in mice through activation of the ERK pathway. Mediators Inflamm. 2012, 2012: 956509-

Bradford MM: A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976, 72: 248-254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3.

Bozza PT, Yu W, Weller PF: Mechanisms of formation and function of eosinophil lipid bodies: inducible intracellular sites involved in arachidonic acid metabolism. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997, 92 (Suppl 2): 135-140. 10.1590/S0074-02761997000800018.

Hamelmann E, Schwarze J, Takeda K, Oshiba A, Larsen GL, Irvin CG, Gelfand EW: Noninvasive measurement of airway responsiveness in allergic mice using barometric plethysmography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997, 156: 766-775.

Figueiredo CC, Deccache PM, Lopes-Bezerra LM, Morandi V: TGF-beta1 induces transendothelial migration of the pathogenic fungus Sporothrix schenckii by a paracellular route involving extracellular matrix proteins. Microbiology. 2007, 153: 2910-2921. 10.1099/mic.0.2006/005421-0.

Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick CR: Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest. 1973, 52: 2745-2756. 10.1172/JCI107470.

Dos Santos MC, Burth P, Younes-Ibrahim M, Goncalves CF, Santelli RE, Oliveira EP, de Castro Faria MV: Na/K-ATPase assay in the intact guinea pig liver submitted to in situ perfusion. Anal Biochem. 2009, 385: 65-68. 10.1016/j.ab.2008.10.046.

Viriyakosol S, Matthias MA, Swancutt MA, Kirkland TN, Vinetz JM: Toll-like receptor 4 protects against lethal Leptospira interrogans serovar icterohaemorrhagiae infection and contributes to in vivo control of leptospiral burden. Infect Immun. 2006, 74: 887-895. 10.1128/IAI.74.2.887-895.2006.

Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B: Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998, 282: 2085-2088. 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085.

Pereira MM, Da Silva JJ, Pinto MA, Da Silva MF, Machado MP, Lenzi HL, Marchevsky RS: Experimental leptospirosis in marmoset monkeys (Callithrix jacchus): a new model for studies of severe pulmonary leptospirosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005, 72: 13-20.

Liang M, Tian J, Liu L, Pierre S, Liu J, Shapiro J, Xie ZJ: Identification of a pool of non-pumping Na/K-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2007, 282: 10585-10593. 10.1074/jbc.M609181200.

Li Z, Xie Z: The Na/K-ATPase/Src complex and cardiotonic steroid-activated protein kinase cascades. Pflugers Arch. 2009, 457: 635-644. 10.1007/s00424-008-0470-0.

Younes-Ibrahim M, Burth P, Faria MV, Buffin-Meyer B, Marsy S, Barlet-Bas C, Cheval L, Doucet A: Inhibition of Na, K-ATPase by an endotoxin extracted from Leptospira interrogans: a possible mechanism for the physiopathology of leptospirosis. C R Acad Sci III. 1995, 318: 619-625.

Mutlu GM, Machado-Aranda D, Norton JE, Bellmeyer A, Urich D, Zhou R, Dean DA: Electroporation-mediated gene transfer of the Na+, K + -ATPase rescues endotoxin-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007, 176: 582-590.

Lacroix-Lamande S, d’Andon MF, Michel E, Ratet G, Philpott DJ, Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Vandewalle A, Werts C: Downregulation of the Na/K-ATPase pump by leptospiral glycolipoprotein activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 2012, 188: 2805-2814. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101987.

Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA: The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012, 122: 2731-2740. 10.1172/JCI60331.

Dorigatti F, Brunialti MK, Romero EC, Kallas EG, Salomao R: Leptospira interrogans activation of peripheral blood monocyte glycolipoprotein demonstrated in whole blood by the release of IL-6. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2005, 38: 909-914. 10.1590/S0100-879X2005000600013.

Foey AD, Crawford A, Hall ND: Modulation of cytokine production by human mononuclear cells following impairment of Na, K-ATPase activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997, 1355: 43-49. 10.1016/S0167-4889(96)00116-4.

Brueckmann M, Hoffmann U, Dvortsak E, Lang S, Kaden JJ, Borggrefe M, Haase KK: Drotrecogin alfa (activated) inhibits NF-kappa B activation and MIP-1-alpha release from isolated mononuclear cells of patients with severe sepsis. Inflamm Res. 2004, 53: 528-533. 10.1007/s00011-004-1291-z.

Samuelsson B, Dahlen SE, Lindgren JA, Rouzer CA, Serhan CN: Leukotrienes and lipoxins: structures, biosynthesis, and biological effects. Science. 1987, 237: 1171-1176. 10.1126/science.2820055.

Feng S, Chen W, Cao D, Bian J, Gong FY, Cheng W, Cheng S, Xu Q, Hua ZC, Yin W: Involvement of Na(+), K (+)-ATPase and its inhibitors in HuR-mediated cytokine mRNA stabilization in lung epithelial cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011, 68: 109-124. 10.1007/s00018-010-0444-1.

Ang SF, Sio SW, Moochhala SM, MacAry PA, Bhatia M: Hydrogen sulfide upregulates cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E metabolite in sepsis-evoked acute lung injury via transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 channel activation. J Immunol. 2011, 187: 4778-4787. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101559.

Bozza PT, Bakker-Abreu I, Navarro-Xavier RA, Bandeira-Melo C: Lipid body function in eicosanoid synthesis: an update. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2011, 85: 205-213. 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.04.020.

Melo RC, D’Avila H, Wan HC, Bozza PT, Dvorak AM, Weller PF: Lipid bodies in inflammatory cells: structure, function, and current imaging techniques. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011, 59: 540-556. 10.1369/0022155411404073.

Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012, 307: 2526-2533.

Dolhnikoff M, Mauad T, Bethlem EP, Carvalho CR: Pathology and pathophysiology of pulmonary manifestations in leptospirosis. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007, 11: 142-148. 10.1590/S1413-86702007000100029.

Marchiori E, Lourenco S, Setubal S, Zanetti G, Gasparetto TD, Hochhegger B: Clinical and imaging manifestations of hemorrhagic pulmonary leptospirosis: a state-of-the-art review. Lung. 2011, 189: 1-9. 10.1007/s00408-010-9273-0.

Plank R, Dean D: Overview of the epidemiology, microbiology, and pathogenesis of Leptospira spp. in humans. Microbes Infect. 2000, 2: 1265-1276. 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01280-6.

Goncalves AJ, de Carvalho JE, Guedes e Silva JB, Rozembaum R, Vieira AR: [Hemoptysis and the adult respiratory distress syndrome as the causes of death in leptospirosis. Changes in the clinical and anatomicopathological patterns]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1992, 25: 261-270. 10.1590/S0037-86821992000400009.

Nally JE, Chantranuwat C, Wu XY, Fishbein MC, Pereira MM, Da Silva JJ, Blanco DR, Lovett MA: Alveolar septal deposition of immunoglobulin and complement parallels pulmonary hemorrhage in a guinea pig model of severe pulmonary leptospirosis. Am J Pathol. 2004, 164: 1115-1127. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63198-7.

Rocco PR, Pelosi P: Pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome: myth or reality?. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008, 14: 50-55.

Fanton d’Andon M, Quellard N, Fernandez B, Ratet G, Lacroix-Lamande S, Vandewalle A, Boneca IG, Goujon JM, Werts C: Leptospira Interrogans Induces Fibrosis in the Mouse Kidney through Inos-Dependent, TLR- and NLR-Independent Signaling Pathways. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014, 8: e2664-10.1371/journal.pntd.0002664.

Pierre SV, Xie Z: The Na, K-ATPase receptor complex: its organization and membership. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2006, 46: 303-316. 10.1385/CBB:46:3:303.

Rocafull MA, Thomas LE, del Castillo JR: The second sodium pump: from the function to the gene. Pflugers Arch. 2012, 463: 755-777. 10.1007/s00424-012-1101-3.

Xie Z, Cai T: Na + -K + –ATPase-mediated signal transduction: from protein interaction to cellular function. Mol Interv. 2003, 3: 157-168. 10.1124/mi.3.3.157.

Edwards A, Pallone TL: Ouabain Modulation of Cellular Calcium Stores and Signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007, 293 (5): F1518-F1532.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Inflammation Laboratory of FIOCRUZ for whole-body plethysmograph data acquisition. This work received financial support from Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Programa Estratégico de Apoio à Pesquisa em Saúde (PAPES), FIOCRUZ, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). The authors acknowledge the following institutions where this work was accomplished: Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ), Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), and Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors state that they have no competing interest to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

CFGA – Conception and design of the experiments; participation in the drafting of the manuscript and direct participation in the experiments. PB – Performance of the Na/K-ATPase experiments based on Rb+ incorporation. ARS - Performance of the animal manipulations and aid in drafting the manuscript. IMMM and FMJO - Participation in the animal experiments. GSL and EDS - In charge of Leptospira culture; CIS - Performed in vitro experiments. VM - In charge of the design of the experiments with HUVECs and cell culture; PTB - In charge of the lipid bodies and of the design of the lipid mediator experiments. RES and ASF - Performance of data acquisition and analysis of the Na/K-ATPase results on Rb+ incorporation. MYI - Participation in the experimental design and in manuscript drafting. HCCFN - Conception of the study, participation in its design and aid in drafting the manuscript. MVCF - Conception of the study, participation in the manuscript drafting and approval of the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque, C.F., Burth, P., Silva, A.R. et al. Murine lung injury caused by Leptospira interrogans glycolipoprotein, a specific Na/K-ATPase inhibitor. Respir Res 15, 93 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-014-0093-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-014-0093-2