Abstract

Background

Sub-Saharan Africa has seen substantial reductions in cases and deaths due to malaria over the past two decades. While this reduction is primarily due to an increasing expansion of interventions, urbanisation has played its part as urban areas typically experience substantially less malaria transmission than rural areas. However, this may be partially lost with the invasion and establishment of Anopheles stephensi. A. stephensi, the primary urban malaria vector in Asia, was first detected in Africa in 2012 in Djibouti and was subsequently identified in Ethiopia in 2016, and later in Sudan and Somalia. In Djibouti, malaria cases have increased 30-fold from 2012 to 2019 though the impact in the wider region remains unclear.

Methods

Here, we have adapted an existing model of mechanistic malaria transmission to estimate the increase in vector density required to explain the trends in malaria cases seen in Djibouti. To account for the observed plasticity in An. stephensi behaviour, and the unknowns of how it will establish in a novel environment, we sample behavioural parameters in order to account for a wide range of uncertainty. This quantification is then applied to Ethiopia, considering temperature-dependent extrinsic incubation periods, pre-existing vector-control interventions and Plasmodium falciparum prevalence in order to assess the potential impact of An. stephensi establishment on P. falciparum transmission. Following this, we estimate the potential impact of scaling up ITN (insecticide-treated nets)/IRS (indoor residual spraying) and implementing piperonyl butoxide (PBO) ITNs and larval source management, as well as their economic costs.

Results

We estimate that annual P. falciparum malaria cases could increase by 50% (95% CI 14–90) if no additional interventions are implemented. The implementation of sufficient control measures to reduce malaria transmission to pre-stephensi levels will cost hundreds of millions of USD.

Conclusions

Substantial heterogeneity across the country is predicted and large increases in vector control interventions could be needed to prevent a major public health emergency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sub-Saharan Africa, where 94% of the global malaria burden occurs, has seen a substantial reduction in cases and deaths due to malaria over the past two decades [1]. While this reduction is primarily due to an increase in investment and expansion of interventions such as insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), and diagnosis and treatment, urbanisation also has played a part.

Africa has experienced rapid urbanisation in recent years, rising from 31.5% of the population living in urban areas in 1990 to 42.5% in 2018. By 2050, approximately 60% of the population is expected to live in urban areas [2]. Planned urbanisation will likely have a positive effect on reducing the malaria burden in Africa, as urban areas typically experience substantially lower rates of malaria transmission than rural areas [3]. Primarily, this is thought to be due to improved housing and the reduced availability of suitable larval habitats for African Anopheles vector species [4].

The protective effect conferred by urbanisation may be partially lost with the invasion and establishment of Anopheles stephensi. An. stephensi is found throughout South Asia, where it is capable of transmitting both Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax parasites [5] in a diverse set of habitats, from rural to highly urban settings [6]. The success of this vector in urban locations is due to its ability to utilise water tanks, wells and other artificial containers as larval habitats [7, 8]. Furthermore, it has shown substantial resistance to water pollution [9]. In the last decade, Anopheles stephensi has been discovered outside of its traditional endemic region in Asia and was first detected in Djibouti in 2012 [10].

Prior to 2013, Djibouti had reported less than 3000 cases of malaria per year. Following the year of initial detection of An. stephensi, cases have increased substantially, and in 2019, there were 49,402 confirmed cases of malaria [11]. While causation has not been established between increasing An. stephensi detection and malaria incidence in Djibouti, it has been heavily implicated [12]. Anopheles stephensi has now been found in Sudan, Somalia and Ethiopia [13,14,15,16,17].

Here, we quantify the potential impact of An. stephensi invasion in Djibouti on malaria transmission in order to make projections about what could happen in Ethiopia, where the species has been found at numerous sites and is spreading [18]. Translating the invasion of An. stephensi to its public health impact is difficult due to uncertainty in its vectorial capacity and how public health entities and governments will respond. Different illustrative scenarios are investigated, exploring the public health impact of different vector control interventions.

Methods

Mechanistic malaria model

A deterministic version of a well-established compartmental model of P. falciparum malaria transmission [19,20,21,22,23,24] was utilised. The human population was split into susceptible or infected individuals with those infected being either asymptomatic, having clinical disease, sub-microscopic infections, having been treated, or being in a period of prophylaxis following treatment. The numbers of mosquito larvae, pupae and adults were simulated with adult mosquitoes being either susceptible, exposed or infectious (after the extrinsic incubation period, EIP). The model accounts for heterogeneity in transmission as well as age-dependent mosquito biting rates and the acquisition of natural immunity. The model is summarised in Additional file 1 Section 1 [19, 20, 22, 23, 25,26,27,28].

Vector bionomics and Latin hypercube sampling

The epidemiological impact of An. stephensi invasion will depend on the characteristics of the vector in the new environment. Vector behaviours such as crepuscular biting and resting outside of houses could translate, compared to other African Anopheles species, to a reduced efficacy of interventions such as ITN and IRS, and therefore accurate parameterisation is important. A literature search was undertaken to find A. stephensi-specific bionomic data to parameterise the mechanistic model. These included the daily mortality, proportion of blood meals taken on humans, endophily (the proportion of time spent in human dwellings), bites taken indoors and in sleeping spaces. Data on A. stephensi behaviour within Africa was sparse, and so estimates were primarily acquired from studies in Iran, India and Pakistan, with limited data from Ethiopia. A full list of studies and parameter range estimates are in the Additional file 1 Section 2 [5], (https://www.worldpop.org/), [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

Due to the relatively low number of studies from which the data were collected, and large uncertainty around how the vector would behave, we incorporated parameter sampling in the model fitting and extrapolation stage. This was done through taking the median value from the data, and sampling from values 25% smaller and 25% larger unless otherwise stated (Additional file 1 Section 2). From this, we undertook Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) which is a statistical method for generating near-random samples of parameter values from a multidimensional distribution. This allowed us to efficiently sample different parameter combinations in order to generate broad uncertainty in predictions [55].

The efficacy of current and future ITNs will also depend on the level of pyrethroid resistance. Substantial pyrethroid resistance has been found in Ethiopia, with a mean across years and sites of 57% mosquito survival upon exposure to pyrethroids in a discriminating dose bioassay [18]. This value was assumed throughout the country. There is no clear picture of how An. stephensi abundance will change seasonally in Ethiopia, and so mosquito density was assumed to remain consistent throughout the year, similar to recent patterns reported in Djibouti (Seyfarth et al. 2019). Ethiopia is geographically diverse, with many regions at high altitudes, reducing malaria transmission. The relationship of the extrinsic incubation period and temperature were provided from Stopard et al. (2021) [32]. How this influences transmission is outlined in the Additional file 1 Section 2 and Section 3.

Fitting to Djibouti data

The severity of the public health impact of A. stephensi invasion will depend on the number of mosquitoes per person (vector density) and how it changes over time. In the absence of information on the speed and magnitude of A. stephensi establishment in Ethiopia, we made the simplest assumption that density increases in a sigmoidal manner that mirrors what has happened in Djibouti. Here, given the low levels of malaria reported prior to A. stephensi detection, we assumed that the increase is singly due to A. stephensi, though native Anopheles species such as A. arabiensis are present. This process is conducted in conjunction with 200 LHS parameterisations of vector bionomics. From this, we take the 100 best LHS combinations as defined by their likelihood and calculate the 2.5, 50 and 97.5% quantiles. This provides us with estimates of the vector density required to explain malaria incidence in Djibouti (Additional file 1 Section 3). We then take the vector density required to explain the final year where it appears to have plateaued, 2019, and apply this to Ethiopia. Here, the increase in vector density does not have an effect on pre-existing population dynamics, in the absence of existing information on the interaction of A. stephensi and local Anopheles vectors, we do not model interaction or replacement, and so the existing vector density is increased by the value estimated above.

Current level of disease

Estimates of the geographical distribution of malaria within Ethiopia were generated from malaria slide prevalence in 2–10-year-old estimates extracted using the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP) R package, malariaAtlas [56]. These were aggregated to the 3rd administrative division (woreda) using a population weighted mean. Estimates were adjusted so that the number of cases predicted by the model matched those reported in the World Malaria Report (WMR). In 2019 (the last year data were available), a total of 738,155 cases of P. falciparum malaria were reported in Ethiopia. Here, we concentrate on Falciparum malaria as this is the dominant malaria species with the biggest public health impact. Current estimates of the level of malaria control in Ethiopia are assumed to be maintained throughout the period of A. stephensi invasion. ITN usage was provided at the 1st administrative division (region) assuming pyrethroid-only ITNs, and IRS coverage at the woreda level [57]. Human population sizes were taken from the UN World Population Prospects (https://www.worldpop.org/). The historical use of antimalarial drug treatment was also extracted from malariaAtlas (Additional file 1 Section 2) and is assumed to remain constant over time. In order to reduce computational demands, the prevalence was rounded to 0, 1, 5, 10, 15 and 25%, historical ITN/IRS/treatment to the nearest 20%, and EIP the nearest 1 day. This reduced the number of administrative locations considered from 690 3rd administrative (woreda) units to 64 administrative groupings (see Additional file 1 Section 2).

Projections of future malaria burden

Models were used to project the change in malaria prevalence over time following the invasion of A. stephensi. Here, we assumed an equal and simultaneous introduction in all groupings, which while unrealistic is the most parsimonious response (Additional File, Section 4 [28, 54, 58, 59]). Simulations were run for each administrative grouping. It is likely that A. stephensi will not invade all regions of the country [30] and that invasion in areas above an altitude of 2000m is unlikely to result in an increased malaria burden due to the low temperatures. We therefore estimated the increase in the number of malaria cases in the population within areas found suitable by previous research [30] and beneath 2000 m [31].

Different vector control interventions are considered to mitigate the impact of A. stephensi invasion. As possible scenarios, we investigated the potential impact of increasing ITN usage, deploying IRS and larval source management (LSM). ITN usage was increased from its current level (Additional file 1 Section 2) up to 80% usage assuming mass distribution every 3 years (assuming pyrethroid-only ITNs). For the implementation of synergist piperonyl butoxide (PBO) via PBO-pyrethroid ITNs, the usage of 0% was assumed and scale-up involved replacing all existing standard pyrethroid-only ITNs. Pyrethroid-only and PBO-pyrethroid ITNs efficacy and its decay over their lifespan is estimated from a meta-analyses of experimental hut trial data as detailed in Churcher et al. (2016) [27]. Models parameterised with these data have been able to recreate the epidemiological impact of the mass distribution of pyrethroid-only ITNs, PBO-pyrethroid ITNs and IRS measured in cluster randomised control trials in Tanzania and Uganda [24]. In costing future interventions, we subtracted the cost of existing ITN usage, as we were calculating the additional cost. IRS covering 80% of structures of human habitation is conducted annually with a long-lasting product which the local mosquito population is fully susceptible to; this decays throughout the year as previously described [60]. The impact of LSM against A. stephensi is highly unclear, but in the absence of this information, it was assumed to be constant and at a level to reduce adult emergence across the year by 40%. These values were chosen based on pre-existing usage/coverage in Ethiopia (Additional file 1 Section 2) and from discussions with implementation partners at the Presidents Malaria Initiative (PMI) centred around desired values and feasibility. Note that some of the intervention combinations are not currently recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) but are considered for completeness. To illustrate the broad economic cost of this additional vector control, simple estimates of total costs are provided. Approximate estimates of the cost of intervention (purchasing, delivering and applying) were provided from literature and from the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (Additional file 1 Section 2).

Results

Projected changes in malaria epidemiology

The establishment of A. stephensi is predicted to increase the malaria burden across Ethiopia according to pre-existing transmission levels, interventions and vector bionomics. Here, we show the increases in the prevalence and incidence following introduction and establishment of A. stephensi under their current levels of vector control.

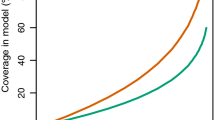

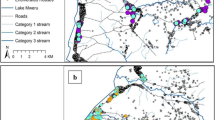

As an example, three locations at very low (~0.1%), low (~2.5%) and moderate (~12%) current P. falciparum prevalence are displayed (Fig. 2). In all example locations, the introduction of A. stephensi leads to increased prevalence, with the most substantial increases in areas with the lowest existing transmission (~0.1%), though estimates are highly uncertain (Fig. 1A). The rate at which the prevalence increases depends on the current levels of transmission, with areas at current negligible levels of transmission taking substantially longer than those areas with current moderate-high transmission to reach the new level of endemicity after mosquito establishment. Sub-nationally, there is considerable variation in the projected increases in prevalence, with some administrative groupings experiencing on average minimal (~0%) increases to absolute prevalence following A. stephensi establishment and others increasing by ~5.5% (Fig. 1B). Overall, the median absolute parasite prevalence increase is ~2.5% in administrative regions, from ~1.6% pre-A. stephensi. At a national level, we predict a median increase of ~368,000 (95% CI 103,000–664,000) clinical P. falciparum malaria cases annually, from a report of ~740,000 in 2019 [1]. This represents a ~49.7% (95% CI 13.9–89.7%) increase if A. stephensi only establishes itself in areas previously found suitable and located under 2000m (Fig. 1C). Substantially, greater increases are seen if A. stephensi invades the whole country and can establish malaria transmission at higher altitudes (Additional file 1 Section 3). Temporal changes in clinical incidence over time for the different settings are shown in Fig. 2. There is considerable uncertainty in the number of clinical cases following invasion, especially in areas with very low history of malaria where populations have no pre-existing immunity to the disease. Here, some model runs projected a substantial increase in malaria cases (greater than in areas with higher malaria prevalence) following a subsequent decline over time that is driven by model assumptions on the acquisition of immunity to clinical disease.

The impact of A. stephensi introduction on malaria prevalence and incidence in areas of Ethiopia in areas under 2000m and identified to be suitable. A Changes in prevalence following introduction and establishment of A. stephensi in 3 areas of malaria transmission in Ethiopia. Vertical dashed lines span the period in which A. stephensi is introduced and coloured shapes the 95% CIs. Green represents a transmission scenario of ~12% prevalence, orange, 2.5% and purple <0.1%. The time scale on the x-axis is deliberately omitted as the rate of invasion is highly uncertain. Prevalence fluctuating due to pre-existing and ongoing mass distribution of ITNs. B The median difference of P. falciparum prevalence following establishment in the different administrative groupings which have been predicted to be suitable based on Sinka et al. (2020) and under 2000m. C The annual increase in clinical incidence of malaria caused by P. falciparum nationally. Individual dots show uncertainty in predictions given differences in mosquito bionomics (for 100 samples of the Latin hyper cube). Periodicity is caused by ongoing distribution of ITNs and IRS which are assumed to continue at pre-invasion levels. For Fig. 1B, C there is no x-axis, and points are jittered for visualisation purposes and to aid ease of interpretation rather than to connote a certain value

The effect of control measures on mitigating the impact of A. stephensi introduction for regions with different pre-existing malaria endemicity. A The change in clinical incidence over time (per 100,000 people per year) following A. stephensi introduction in three locations, with low (~0.1%), medium (~2.5%) and high slide prevalence (~12%). Each location had an EIP of 8 and 40% ITN usage, 0% IRS and 0% LSM pre-A. stephensi introduction and establishment. To aid clarity and interpretation of the figure, we only display the temporal trends of the PBO-ITN and PBO-ITN/IRS/LSM package of interventions, though the impacts of all modelled interventions are displayed in Fig. 2B. Different coloured lines indicate intervention scenarios be it no additional interventions (black), or scale up of PBO-ITNs (blue) or the use of PBO-ITN/IRS/LSM. Coloured shapes show the 95% CIs for model predictions given uncertainty in parameters. The left vertical dashed line indicates the start to the introduction of An. stephensi, which occurs between the dashed lines and is fully established by year 3. As above, the time scale on the x-axis is deliberately omitted due to uncertainty in the timing of events, with clinical incidence fluctuating with 3-year ITN mass campaigns and annual IRS. Additionally, uncertainty continues up to 400 cases per 100,000, but this has been curtailed in order to improve interpretation of median trends. B The median annual increase in malaria incidence per 100,000 per year comparing before and after scenarios for each of the locations across a range of intervention combinations. Red arrows and numbers refer to the percentage increase in the median incidence following the establishment of A. stephensi compared to the 3 years prior to the introduction. Black lines and numbers show the percentage reduction in cases relative to no additional interventions over 3 years caused by the introduction of the different control interventions

Impact of increasing vector control

The impact of additional vector control interventions following A. stephensi establishment is dependent on the level of transmission, pre-existing use of interventions and vector bionomics. Mosquito characteristics such as the proportion of bites taken indoors are unknown and can substantially influence the effectiveness of ITNs and IRS (Additional file 1 Section 4). Here, we have selected three locations with the same pre-existing intervention usage/coverage and EIP values, but differing levels of pre-existing transmission, in order to illustrate how disease endemicity can influence temporal dynamics (Fig. 2). In some circumstances, the model predicts that scaling up of standard ITNs, IRS or LSM in combination is sufficient to suppress malaria to pre-A. stephensi levels and sometimes beyond (Fig. 2A).

In areas with low levels of transmission (~0.1%), increases in incidence are substantial, and in order to reduce transmission to pre-An. stephensi levels of transmission, a suite of interventions must be considered (Fig. 2B). At higher levels of transmission (~12%), the implementation of PBO-ITNs alone may be suitable to initiate a reduction; however, if only pyrethroid-ITNs are available, they should be used in conjunction with IRS and LSM to reduce transmission to pre-A. stephensi levels (Fig. 2B). The efficacy of LSM in the area is highly unclear, but a 40% reduction in mosquito emergence is predicted to have a larger impact in areas of lower endemicity; conversely, ITNs are predicted to be more effective at higher endemicities. The extent of IRS impact is unclear. Overall, we find that if using standard pyrethroid-only ITNs, a combination of ITN/IRS/LSM is needed to reduce national P. falciparum incidence to pre-A. stephensi levels. However, given the unknowns in A. stephensi responses to these interventions, even this may be insufficient (Table 1, Fig. 2B).

The mass distribution of PBO-pyrethroid nets may offer a more cost-effective tool given the high levels of pyrethroid resistance and relatively low levels of endophily in Ethiopian A. stephensi populations (Fig. 2 and Table 1). PBO-pyrethroid nets are predicted to have the most substantial impact on transmission of any single intervention examined and almost achieves the reduction provided by a combination of standard ITNs, IRS and LSM (139,000 (60,000–157,000) vs 194,000 (44,000–410,000) cases averted). Furthermore, PBO-pyrethroid nets only account for a fraction of the cost of this more comprehensive intervention packet, $3.5 (2.9–3.7) vs $70.3 million USD (38.4–100.9).

Layering multiple vector control interventions are predicted to have the largest impact. However, because of the number of sites with minimal malaria transmission before A. stephensi invasion, this may be insufficient to push the national malaria burden beneath current levels unless PBO-pyrethroid nets, higher usage/coverage (ITNs, IRS) or improved effectiveness (LSM) can be achieved (Table 1). Increases in IRS coverage to 80% alone offers substantial improvements due to the relatively limited use of IRS currently nationwide (Additional file 1 Section 2). However, due to low rates of endophily and crepuscular biting, the impact is substantially less than would be expected against African Anopheles species. The cost of implementing interventions is expected to be substantial, with the most comprehensive set of interventions (80% use of PBO-pyrethroid ITN and IRS, 40% reduction in adult emergence) estimated to cost an additional $72.0 million USD ($39.9–$102.5 million) annually or $238 USD ($117–$505) per case averted (over existing malaria prevention budgets).

Discussion

The invasion and establishment of Anopheles stephensi represents an imminent and substantial threat to the Horn of Africa and wider region which could jeopardise progress achieved in malaria control. The modelled increase in malaria is highly uncertain, but without additional interventions, the impact could be considerable, with an estimated ~50% increase from the reported ~740,000 P. falciparum malaria cases in Ethiopia, 2019, to an estimated 1,130,000 (95% CI 843,000–1,404,000) after establishment and disease equilibrium has been reached. This assumes that malaria cases only increase in areas previously predicted as suitable for A. stephensi establishment located under 2000m. Numbers could be substantially higher if invasion is more widespread.

Sub-nationally, significant heterogeneity in public health impact is expected. Analysis suggests that low altitude urban areas at pre-existing low levels of malaria transmission may experience the largest increases in disease burden. In these areas, the absence of existing vector control and low human population immunity indicates the possibility for substantial increases in transmission. These areas are also the most uncertain, with the model predicting the increase that clinical cases could be negligible to more than that observed in areas where malaria has historically been widespread. Our finding that areas with low pre-existing levels of transmission (much of Ethiopia) take substantially longer to see increases in malaria after A. stephensi introduction is particularly worrying. In these locations, in the absence of widespread and routine surveillance for A. stephensi, the first signal detected could be an increase in malaria, which would occur a considerable amount of time after mosquito establishment. While this would not be of significant concern if the vector was easily removed or only led to a relatively minor and easily combatable increase in malaria, our model findings and what has been observed in Djibouti [11, 12] suggest that this is not the case. Once A. stephensi becomes established, it could lead to significant increases in malaria transmission that are not easily reversed. This unnoticed proliferation and subsequent increase in transmission were previously seen in Anopheles arabiensis in North-Eastern Brazil, where its ‘silent spread’ led to a large malaria epidemic [30, 61]. Nevertheless, this work shows that the absence of an increase in reported malaria cases following the identification of the presence of A. stephensi should not be overly interpreted.

To combat the possible increase of malaria transmission following An. stephensi establishment, the deployment of a wide array of vector control interventions should be considered. High levels of pyrethroid resistance observed in A. stephensi captured in Ethiopia [17, 18] suggest that pyrethroid-only ITNs (already in use across the country) will have a limited efficacy for control of malaria transmitted by A. stephensi. Adoption of PBO-ITNs is predicted to be both highly impactful and cost-effective. The impact of different control interventions is unclear given the receptiveness of A. stephensi in this new environment is unquantified. For example, if the mosquito feeds at night and rests inside structures sprayed with IRS, then the widespread use of this intervention alone could be sufficient to mitigate the public health impact (Additional file 1 Section 4). However, if the mosquito was less amenable to indoor vector control, then layering of ITNs and IRS may be insufficient. Within its endemic range, A. stephensi shows a propensity to both crepuscular biting and resting outside of houses compared to African Anopheles species, suggesting a reduced efficacy if it behaves as it does in its endemic range [30] (Additional file 1 Section 2). Compounding this, high-density urban locations, where large-scale vector-control campaigns have been historically absent, will present a challenge for establishing ITN access and use as well as achieving sufficient IRS coverage. While A. stephensi is primarily known as an urban vector of malaria, it is found in both urban and rural settings across its endemic range [30] and in Ethiopia [18], and so there is the potential for its impact on malaria transmission to be found across the country. Differences in environment, housing, culture, human and vector behaviour in urban and rural settings are likely to result in very different public health outcomes, even before considering the logistics of intervention deployment. Though these factors are likely to have a substantial effect, it is presently unknown how these combined factors will translate into malaria transmission and control. In the absence of quantified and validated input data, we have not stratified models by urbanicity at this present time. Nevertheless, additional data on A. stephensi bionomics and the impact of vector control interventions, stratified across urban/rural areas and housing types, should therefore be collected as a matter of urgency to enable model estimates to be refined and contribute to the decision-making process (Additional file 1 Section 4). These compound uncertainties combined with the crude method of economic evaluation adopted here make cost projections highly variable. Though these are substantial ($74.6 million USD ($42.6–$105.4)), the economic burden of an additional ~368,000 (95% CI 103,000–664,000) malaria cases should not be underestimated.

This work was intended to provide initial estimates of the possible scale and impact of A. stephensi invasion rather than detailed predictions of what will happen. As such, there are many limitations to this approach (further detailed in the Additional file 1 Section 4) and results should not be overly interpreted. The public health impact is likely to be underestimated as we only consider P. falciparum malaria, despite A. stephensi having been shown to be capable of efficiently transmitting P. vivax in Ethiopia [54]. Due to the presence of additional Anopheles species in Djibouti, it is unlikely the increases we have seen are purely due to A. stephensi, which we have assumed, and while highly correlated [11], and increasingly implicated [12], the causative role in A. stephensi in the increases seen in Djibouti has not been established. However, the trends observed along with evidence of underreporting in Djibouti are cause for significant concern [12]. Malaria burden is related to the extent to which A. stephensi may invade a region (i.e. the number of mosquitoes per person and not just its presence) and the seasonality of the vector. Malaria transmission is often highly seasonal and an important factor when evaluating local epidemiology and vector control. However, the case of A. stephensi seasonality is a complicated and currently unquantified unknown. Across its endemic range, A. stephensi shows a variety of patterns from unimodal to bimodal to peaking in the dry season to the wet [62], and within Ethiopia, there is a dearth of this data. As we are not modelling seasonally timed interventions, and are concerned with long term rather than intra-annual dynamics, the omission of seasonality in our model does not change model predictions or recommendations, though the quantification of A. stephensi seasonality in the Horn of Africa should be a matter of urgent study.

Conclusions

While we have made use of available published and unpublished sources on A. stephensi bionomics, there is either insufficient data or substantial intra-species variability to simply ascribe a set of characteristics to how A. stephensi will interact with humans and control interventions in Ethiopia. In order to improve predictions, we have identified priority aspects of A. stephensi bionomics (such as anthropophagy, endophily, indoor biting), local transmission (existing distribution of malaria cases between rural and urban areas) and intervention parameters (efficacy of ITNs, IRS and LSM give a certain effort) that should be explored as a priority in order to inform additional mathematical modelling of the impact of A. stephensi on malaria transmission in Africa (see Additional Section 4).

Though there is substantial uncertainty in what will happen if An. stephensi becomes established in Ethiopia and other locations across Africa, the estimates provided here, and the situation seen in Djibouti, should be a stark warning against complacency and highlight the need to rapidly improve surveillance and evaluate effective control interventions in response to this developing threat.

Availability of data and materials

All data and code required to run the analysis is provided at https://github.com/arranhamlet/stephensi_ETH_publication [63]

Abbreviations

- EIP:

-

Extrinsic incubation period

- IRS:

-

Indoor residual spraying

- ITN:

-

Insecticide-treated nets

- LHS:

-

Latin hypercube sampling

- LSM:

-

Larval Source Management

- MAP:

-

Malaria Atlas Project

- PBO:

-

Piperonyl butoxide

- PMI:

-

Presidents malaria initiative

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WMR:

-

World Malaria Report

References

World Health Organization. World malaria report 2020: 20 years of global progress and challenges. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

United Nations. DoEaSA, Population Division. World urbanization prospects: the 2018 revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420). New York: United Nations; 2019.

Hay SI, Guerra CA, Tatem AJ, Atkinson PM, Snow RW. Urbanization, malaria transmission and disease burden in Africa. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(1):81–90.

Trape JF, Zoulani A. Malaria and urbanization in Central Africa: the example of Brazzaville. Part III: relationships between urbanization and the intensity of malaria transmission. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81(Suppl 2):19–25.

Thomas S, Ravishankaran S, Justin NA, Asokan A, Mathai MT, Valecha N, et al. Resting and feeding preferences of Anopheles stephensi in an urban setting, perennial for malaria. Malar J. 2017;16(1):111.

Subbarao SK, Nanda N, Rahi M, Raghavendra K. Biology and bionomics of malaria vectors in India: existing information and what more needs to be known for strategizing elimination of malaria. Malar J. 2019;18(1):396.

Kumar A, Thavaselvam D. Breeding habitats and their contribution to Anopheles stephensi in Panaji. Indian J Malariol. 1992;29(1):35–40.

Gayan Dharmasiri AG, Perera AY, Harishchandra J, Herath H, Aravindan K, Jayasooriya HTR, et al. First record of Anopheles stephensi in Sri Lanka: a potential challenge for prevention of malaria reintroduction. Malar J. 2017;16(1):326.

Batra CP, Adak T, Sharma VP, Mittal PK. Impact of urbanization on bionomics of an. Culicifacies and an. Stephensi in Delhi. Indian J Malariol. 2001;38(3-4):61–75.

Faulde MK, Rueda LM, Khaireh BA. First record of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi and its possible role in the resurgence of malaria in Djibouti. Horn Africa Acta tropica. 2014;139:39–43.

Seyfarth M, Khaireh BA, Abdi AA, Bouh SM, Faulde MK. Five years following first detection of Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae) in Djibouti, horn of Africa: populations established-malaria emerging. Parasitol Res. 2019;118(3):725–32.

de Santi VP, Khaireh BA, Chiniard T, Pradines B, Taudon N, Larreche S, et al. Role of anopheles stephensi mosquitoes in malaria outbreak, Djibouti, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(6):1697–700.

Global Malaria Programme, World Health Organization. 2022. "Malaria Threats Map." from https://apps.who.int/malaria/maps/threats.

Ahmed A, Khogali R, Elnour MB, Nakao R, Salim B. Emergence of the invasive malaria vector Anopheles stephensi in Khartoum state, Central Sudan. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1):511.

Ahmed A, Pignatelli P, Elaagip A, Abdel Hamid MM, Alrahman OF, Weetman D. Invasive malaria vector Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes in Sudan, 2016-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(11):2952–4.

Carter TE, Yared S, Gebresilassie A, Bonnell V, Damodaran L, Lopez K, et al. First detection of Anopheles stephensi Liston, 1901 (Diptera: culicidae) in Ethiopia using molecular and morphological approaches. Acta Trop. 2018;188:180–6.

Yared S, Gebressielasie A, Damodaran L, Bonnell V, Lopez K, Janies D, et al. Insecticide resistance in Anopheles stephensi in Somali region, eastern Ethiopia. Malar J. 2020;19(1):180.

Balkew M, Mumba P, Yohannes G, Abiy E, Getachew D, Yared S, et al. An update on the distribution, bionomics, and insecticide susceptibility of Anopheles stephensi in Ethiopia, 2018-2020. Malar J. 2021;20(1):263.

Griffin JT, Ferguson NM, Ghani AC. Estimates of the changing age-burden of plasmodium falciparum malaria disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3136.

Challenger JD, Olivera Mesa D, Da DF, Yerbanga RS, Lefèvre T, Cohuet A, et al. Predicting the public health impact of a malaria transmission-blocking vaccine. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1494.

Griffin JT, Hollingsworth TD, Okell LC, Churcher TS, White M, Hinsley W, et al. Reducing plasmodium falciparum malaria transmission in Africa: a model-based evaluation of intervention strategies. PLoS Med. 2010;7(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000324.

White MT, Griffin JT, Churcher TS, Ferguson NM, Basanez MG, Ghani AC. Modelling the impact of vector control interventions on Anopheles gambiae population dynamics. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:153.

Griffin JT, Bhatt S, Sinka ME, Gething PW, Lynch M, Patouillard E, et al. Potential for reduction of burden and local elimination of malaria by reducing plasmodium falciparum malaria transmission: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(4):465–72.

Sherrard-Smith E, Winskill P, Hamlet A, Ngufor C, N'Guessan R, Guelbeogo MW, et al. Optimising the deployment of vector control tools against malaria: a data-informed modelling study. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6(2):e100–9.

Carneiro I, Roca-Feltrer A, Griffin JT, Smith L, Tanner M, Schellenberg JA, et al. Age-patterns of malaria vary with severity, transmission intensity and seasonality in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and pooled analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e8988.

Le Menach A, Takala S, McKenzie FE, Perisse A, Harris A, Flahault A, et al. An elaborated feeding cycle model for reductions in vectorial capacity of night-biting mosquitoes by insecticide-treated nets. Malar J. 2007;6:10.

Churcher TS, Lissenden N, Griffin JT, Worrall E, Ranson H. The impact of pyrethroid resistance on the efficacy and effectiveness of bednets for malaria control in Africa. Elife. 2016;5. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.16090.

Walker PG, Griffin JT, Ferguson NM, Ghani AC. Estimating the most efficient allocation of interventions to achieve reductions in plasmodium falciparum malaria burden and transmission in Africa: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(7):e474–84.

World Population Prospects: The 2020 Revision [http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/]

Sinka ME, Pironon S, Massey NC, Longbottom J, Hemingway J, Moyes CL, et al. A new malaria vector in Africa: predicting the expansion range of Anopheles stephensi and identifying the urban populations at risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(40):24900–8.

Fick SE, Hijmans RJ. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2017;37(12):4302–15.

Stopard IJ, Churcher TS, Lambert B. Estimating the extrinsic incubation period of malaria using a mechanistic model of sporogony. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17(2):e1008658.

Shapiro LLM, Whitehead SA, Thomas MB. Quantifying the effects of temperature on mosquito and parasite traits that determine the transmission potential of human malaria. PLoS Biol. 2017;15(10):e2003489.

Shapiro LL, Murdock CC, Jacobs GR, Thomas RJ, Thomas MB. Larval food quantity affects the capacity of adult mosquitoes to transmit human malaria. Proc Biol Sci. 2016;283(1834). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0298.

Murdock CC, Sternberg ED, Thomas MB. Malaria transmission potential could be reduced with current and future climate change. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27771.

Bompard A, Da DF, Yerbanga SR, Morlais I, Awono-Ambene PH, Dabire RK, et al. High plasmodium infection intensity in naturally infected malaria vectors in Africa. Int J Parasitol. 2020;50(12):985–96.

Manouchehri AV, Javadian E, Eshighy N, Motabar M. Ecology of Anopheles stephensi Liston in southern Iran. Trop Geogr Med. 1976;28(3):228–32.

Mehravaran A, Vatandoost H, Oshaghi MA, Abai MR, Edalat H, Javadian E, et al. Ecology of Anopheles stephensi in a malarious area, southeast of Iran. Acta Med Iran. 2012;50(1):61–5.

Vatandoost H, Oshaghi MA, Abaie MR, Shahi M, Yaaghoobi F, Baghaii M, et al. Bionomics of Anopheles stephensi Liston in the malarious area of Hormozgan province, southern Iran, 2002. Acta Trop. 2006;97(2):196–203.

Mojahedi AR, Safari R, Yarian M, Pakari A, Raeisi A, Edalat H, et al. Biting and resting behaviour of malaria vectors in Bandar-Abbas County, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(10):1218–26.

Basseri HR, Abai MR, Raeisi A, Shahandeh K. Community sleeping pattern and anopheline biting in southeastern Iran: a country earmarked for malaria elimination. Am J Trop Med Hygiene. 2012;87(3):499–503.

Basseri H, Raeisi A, Ranjbar Khakha M, Pakarai A, Abdolghafar H. Seasonal abundance and host-feeding patterns of anopheline vectors in malaria endemic area of Iran. J Parasitol Res. 2010;2010:671291.

Dash AP, Adak T, Raghavendra K, Singh OP. The biology and control of malaria vectors in India. Curr Sci. 2007;92(11):1571–8.

Conn JE, Norris DE, Donnelly MJ, Beebe NW, Burkot TR, Coulibaly MB, et al. Entomological monitoring and evaluation: diverse transmission settings of ICEMR projects will require local and regional malaria elimination strategies. Am J Trop Med Hygiene. 2015;93(3 Suppl):28–41.

Maghsoodi N, Ladonni H, Basseri HR. Species composition and seasonal activities of malaria vectors in an area at reintroduction prevention stage, Khuzestan, South-Western Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2015;9(1):60–70.

Herrel N, Amerasinghe FP, Ensink J, Mukhtar M, van der Hoek W, Konradsen F. Adult anopheline ecology and malaria transmission in irrigated areas of South Punjab, Pakistan. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18(2):141–52.

O’Donnell AJ, Rund SSC, Reece SE. Time-of-day of blood-feeding: effects on mosquito life history and malaria transmission. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12(1):301.

Reisen WK, Boreham PF. Estimates of malaria vectorial capacity for anopheles culicifacies and Anopheles stephensi in rural Punjab province Pakistan. J Med Entomol. 1982;19(1):98–103.

Ghosh A, Mandal S, Chandra G. Seasonal distribution, parity, resting, host-seeking behavior and association of malarial parasites of Anopheles stephensi Liston in Kolkata, West Bengal. Entomological Res. 2010;40(1):46–54.

Reisen WK, Mahmood F. Horizontal life table characteristics of the malaria vectors anopheles culicifacies and anopheles Stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae)1. J Med Entomol. 1980;17(3):211–7.

Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Chareonviriyaphap T, Patil AP, Temperley WH, et al. The dominant anopheles vectors of human malaria in the Asia-Pacific region: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic precis. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:89.

Pramanik MK, Aditya G, Raut SK. A survey of anopheline mosquitoes and malarial parasite in commuters in a rural and an urban area in West Bengal, India. J Vector Borne Dis. 2006;43(4):198–202.

Soleimani-Ahmadi M, Vatandoost H, Shaeghi M, Raeisi A, Abedi F, Eshraghian MR, et al. Field evaluation of permethrin long-lasting insecticide treated nets (Olyset((R))) for malaria control in an endemic area, southeast of Iran. Acta Trop. 2012;123(3):146–53.

Tadesse FG, Ashine T, Teka H, Esayas E, Messenger LA, Chali W, et al. Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes as vectors of plasmodium vivax and falciparum, horn of Africa, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(2):603–7. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2702.200019.

Iman RL. Latin hypercube sampling. In: Wiley StatsRef: statistics reference online; 2014.

Pfeffer DA, Lucas TCD, May D, Harris J, Rozier J, Twohig KA, et al. malariaAtlas: an R interface to global malariometric data hosted by the malaria atlas project. Malar J. 2018;17(1):352.

National Malaria Control and Elimination Programme: A survey on ownership and use of long-lasting insecticidal nets and malaria treatment seeking behavior in Ethiopia (2020). In. Edited by Health Mo. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Public Health Institute; 2020.

Griffin JT. The interaction between seasonality and pulsed interventions against malaria in their effects on the reproduction number. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004057.

Cairns ME, Walker PG, Okell LC, Griffin JT, Garske T, Asante KP, et al. Seasonality in malaria transmission: implications for case-management with long-acting artemisinin combination therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Malar J. 2015;14:321.

Sherrard-Smith E, Griffin JT, Winskill P, Corbel V, Pennetier C, Djenontin A, et al. Systematic review of indoor residual spray efficacy and effectiveness against plasmodium falciparum in Africa. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4982.

Killeen GF, Fillinger U, Kiche I, Gouagna LC, Knols BG. Eradication of Anopheles gambiae from Brazil: lessons for malaria control in Africa? Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(10):618–27.

Whittaker C, Winskill P, Sinka M, Pironon S, Massey C, Weiss DJ, et al. The ecological structure of mosquito population dynamics: insights from India. medRxiv. 2021:2021.2001.2009.21249456. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.09.21249456.

Hamlet A. The potential impact of Anopheles stephensi establishment on the transmission of plasmodium falciparum in Ethiopia and prospective control measureshttps://github.com/arranhamlet/stephensi_ETH_publication/releases/tag/public_release_BMC:github.com; 2022.

Acknowledgements

NA.

Funding

We acknowledge funding support from the United States President’s Malaria Initiative, Wellcome Trust (National Institute for Health Research–Wellcome Partnership for Global Health Research Collaborative Award, ‘Controlling emergent Anopheles stephensi in Ethiopia and Sudan (CEASE), Ref: 220870_Z_20_Z) and the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis (reference MR/R015600/1).The MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis is jointly funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), under the MRC/FCDO Concordat agreement and is also part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union; and acknowledges funding by Community Jameel. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative, Wellcome, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.H, T.C, A.S, S.R.I and J.S.A. Methodology; A.H and T.C. Software: A.H.. Supervision: T.C, A.S, S.R.I and J.S.A. Project administration: T.C, A.S, S.R.I and J.S.A. Data curation: A.H, J.E.T, A.S and S.R.I. Writing: A.H, D.D, J.E.T, F.G.T, T.B, M.S, A.S, S.R.I, J.S.A and T.C. Reviewing: A.H, D.D, J.E.T, F.G.T, T.B, M.S, A.S, S.R.I, J.S.A and T.C. Visualisation: A.H. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable, as all data used was publicly available and modelled rather than individual data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Further details of the mechanistic model and underlying data, further analyses and additional limitations and highlighting useful data for collection to further mathematical modelling. Figure S1. Mechanistic model schematic. Figure S2. Parameters included for each administrative grouping. Figure S3. Relationship of EIP and temperature. Table S1. Mosquito bionomics. Table S2. Grouping of administrative units and values. Table S3. Cost per intervention per person per year. Figure S4. Vector bionomics and fitted incidence to data. Figure S5. Sensitivity analysis on impact across assumptions of population exposed. Table S4. Populations and increases in clinical incidence across assumptions of population exposed. Figure S6. Relationship of prevalence and EIP. Table S5. Key parameters to inform modelling and impacts. Figure S7. Univariate analysis of entomological parameters and incidence. Table S6. Vector bionomics from literature search.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamlet, A., Dengela, D., Tongren, J.E. et al. The potential impact of Anopheles stephensi establishment on the transmission of Plasmodium falciparum in Ethiopia and prospective control measures. BMC Med 20, 135 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02324-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02324-1