Abstract

Background

Over the last decade, progress in reducing maternal mortality in Rwanda has been slow, from 210 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015 to 203 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2020. Access to quality antenatal care (ANC) can substantially reduce maternal and newborn mortality. Several studies have investigated factors that influence the use of ANC, but information on its quality is limited. Therefore, this study aimed to identify the determinants of quality antenatal care among pregnant women in Rwanda using a nationally representative sample.

Methods

We analyzed secondary data of 6,302 women aged 15–49 years who had given birth five years prior the survey from the Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey (RDHS) of 2020 data. Multistage sampling was used to select RDHS participants. Good quality was considered as having utilized all the ANC components. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted to explore the associated factors using SPSS version 25.

Results

Out of the 6,302 women, 825 (13.1%, 95% CI: 12.4–14.1) utilized all the ANC indicators of good quality ANC); 3,696 (60%, 95% CI: 58.6–61.1) initiated ANC within the first trimester, 2,975 (47.2%, 95% CI: 46.1–48.6) had 4 or more ANC contacts, 16 (0.3%, 95% CI: 0.1–0.4) had 8 or more ANC contacts. Exposure to newspapers/magazines at least once a week (aOR 1.48, 95% CI: 1.09–2.02), lower parity (para1: aOR 6.04, 95% CI: 3.82–9.57) and having been visited by a field worker (aOR 1.47, 95% CI: 1.23–1.76) were associated with more odds of receiving all ANC components. In addition, belonging to smaller households (aOR 1.34, 95% CI: 1.10–1.63), initiating ANC in the first trimester (aOR 1.45, 95% CI: 1.18–1.79) and having had 4 or more ANC contacts (aOR 1.52, 95% CI: 1.25–1.85) were associated with more odds of receiving all ANC components. Working women had lower odds of receiving all ANC components (aOR 0.79, 95% CI: 0.66–0.95).

Conclusion

The utilization of ANC components (13.1%) is low with components such as having at least two tetanus injections (33.6%) and receiving drugs for intestinal parasites (43%) being highly underutilized. Therefore, programs aimed at increasing utilization of ANC components need to prioritize high parity and working women residing in larger households. Promoting use of field health workers, timely initiation and increased frequency of ANC might enhance the quality of care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the 2019 World Health Organization's (WHO) report, over 810 maternal deaths are registered every day, with over 94% occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [1]. Most of these deaths could be prevented or significantly reduced through interventions such as receiving quality antenatal care (ANC), skilled birth attendance (SBA) and post-natal care (PNC) [2, 3]. The WHO’s latest ANC recommendations emphasize the importance of every pregnant woman receiving prompt, appropriate, and high-quality care throughout her pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum period [4, 5].

Antenatal care (ANC) can be described as care given to pregnant women by professional health care providers to ensure the best health outcomes for both mothers and babies during pregnancy and child birth [6]. It also serves as an entry point to the utilization of maternal care services. Evidence shows that women that receive quality services during ANC develop confidence in the maternal care services, are more likely to deliver under the care of a skilled birth attendant, and also seek early postnatal care (PNC) [2, 5]. The aim of ANC is to help women sustain normal pregnancies through early identification of preexisting conditions, identifying complications that arise during childbirth, and promotion of well-being [2, 7]. Currently, the WHO guidelines recommend at least eight contacts, with the first one occurring within the first 12 weeks of gestation [8].

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), several countries have reported a significant improvement in the utilisation of ANC services by pregnant women, yet the maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality has remained unacceptably high [7, 9]. Adequate and quality ANC has been documented to contribute towards reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality. Tiruye et al. showed that attending at least one ANC contact can decrease the risk of neonatal death by 42% [10]. However, SSA regions such as East Africa continue to share some of the poorest ANC utilization statistics and a significant share of global maternal and newborn mortality [10, 11]. This may be related to the quality of ANC care that is provided, which has been criticized in several studies from SSA [12]. Recently published data have documented low ANC utilization in East Africa with overall quality of ANC at 11.6%, utilization of at least 4 contacts at 56.4% and use of skilled ANC providers at 78.7% [11, 13]. Countries like Ethiopia have reported the lowest quality of ANC at 5.6% [13]. With the highest proportion of at least four ANC contacts in East Africa observed in Uganda at 61%, this shows the need to prioritize ANC programs in the region to ensure progress in the reduction of maternal and neonatal mortalities [11].

Rwanda was among the countries that achieved the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) 4 and 5 [14, 15] and also registered reduction in the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) from 750 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2005 to 210 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015 [16]. However, very slow progress has been registered between 2015 and 2020 from 210 deaths per 100,000 live births to 203 deaths per 100,000 live births [16]. Furthermore, according to the latest Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey (RDHS), less than half of all the women are able to utilise more than four ANC contacts, yet over 94% deliver under the care of a SBA [16]. This is further supported by a regional paper that shows Rwanda to have the lowest optimal ANC utilization proportion [11]. In order to ensure successful implementation of the latest WHO ANC guidelines that recommend at least eight contacts for every pregnant woman and progress towards reduction of the MMR to less than 70 per 100,000 live births, there is need to explore the different factors such as quality of ANC that might affect utilisation of ANC [4, 8, 17]. In addition to affecting pregnancy outcomes, inadequate quality of care might discourage women from utilizing ANC and other maternal healthcare services [12, 18]. Although several studies that have looked at ANC in Rwanda, no post MDG era national study has been able to extensively evaluate ANC in the country with a focus on the utilization of ANC components and also considering the latest WHO ANC guidelines. Therefore, this study aimed mainly to identify the factors associated with utilization of ANC components among pregnant women in Rwanda using a nationally representative sample of 2020 RDHS.

Methods

Setting

Rwanda located in central-eastern part of Africa is a low-income country with a population of about 12 million people [16, 19]. Rwanda’s public health system comprises of national referral hospitals as the highest level of care followed by provincial hospitals, district hospitals, health centers, and health posts [20, 21]. Community health workers (CHWs) who are over 45,000 provide health services at the village level [20, 22]. These CHWs provide the first line of basic health services with each village having a male–female CHW pair [20]. Rwanda has a universal, community-based health insurance program that has a household subscription and co-payments at the time of care and all citizens are eligible to enroll into it [20, 23]. Community-Based Health Insurance (CBHI) is purchased by about 86% of households [24].

Study design

Cross sectional study to analyze secondary data.

Study sampling and participants

The 2019–20 Rwanda Demographic Survey (RDHS) was used for this analysis. Data collection started in November 2019 and ended in July 2020 taking longer than expected due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions [16]. The Rwanda National Ethics Committee (RNEC) and the ICF Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the survey protocol [16]. The2019-20 RDHS employed a two-stage sample design with the first stage involving sample points (clusters) selection consisting of enumeration areas (EAs) leading to 500 clusters being selected (112 in urban areas and 388 in rural areas) [16]. The second stage involved systematic sampling of households in all the selected EAs leading to a total of 13,005 households [16]. The RDHS used five questionnaires that included: the household, the woman’s, the man’s, the biomarker, and the fieldworker questionnaires. The data used in this analysis were from the household and the woman’s questionnaires.

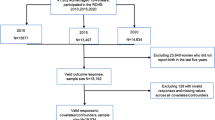

Women aged 15–49 years who were either permanent residents of the selected households or visitors who stayed in the household the night before the survey were eligible to be interviewed. Out of the total 13,005 households that were selected for the survey, 12,951 were occupied and 12,949 were successfully interviewed leading to 100% response rate of 100.0% [16]. This study included women aged 15–49 years who were in need of ANC having had childbirth within five years preceding the survey. For those with more than one birth, the latest birth was considered. Among the interviewed households,14,675 women aged 15–49 were eligible to be interviewed and 14,634 women were successfully interviewed leading to a 99.7% response rate [16]. Out of the 14,634 successfully interviewed women, a weighted sample of 6,302 women had given birth within the last five years preceding the survey as shown in the supplementary file 1.

Variables

Dependent variables

The primary outcome variable was complete utilization of ANC components available in the RDHS women dataset that included: having blood pressure measurement, urine and blood samples being taken, being given iron tablets/syrups and intestinal parasite drugs and having had at least two tetanus injections [25,26,27]. Complete utilization of all the six ANC components was considered a proxy for having received good quality ANC and was coded 1 while inadequate quality was coded zero [25, 28].

The secondary outcomes were timing of ANC initiation and frequency of ANC visits. As recommended by the latest WHO guidelines, early ANC initiation was considered as initiation within the first trimester coded as one and initiation after first trimester coded as zero [27]. Adequate ANC frequency was considered as 4 and more contacts and coded as one and less than 4 contacts coded as zero [2, 6]. However, sensitivity analysis was done using 8 or more contacts as a measure of adequate ANC frequency recommended by the latest WHO guidelines [27].

Independent variables

This study included determinants of ANC initiation timing, frequency and quality based on evidence from available literature and data [6, 16, 25, 28]. Twenty explanatory variables were used in this study as shown in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

RDHS sample weights were used through the analysis to account for the unequal probability sampling in different strata [29] and to ensure representativeness of the findings [30]. In order to account for the multistage sample design inherent in the DHS dataset and to avoid any effect of the study design on the results hence ensuring accurate and reliable results, SPSS version 25.0 statistical software complex samples package was used. The complex samples’ package the analysis plan incorporated the sample individual weight, strata for sampling errors/design, and cluster number used in the RDHS which accounted for the multistage sample design inherent in the RDHS dataset [31,32,33]. Furthermore, use of weights enables making statistical inference at the population level while incorporating strata and cluster ensures getting correct standard error. Bivariable logistic regression was done to assess the association of each independent variable with each outcome and crude odds ratio (COR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-values are presented. Independent variables found significant at bivariable level with p-values less than 0.25 were added in the multivariable logistic regression model. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR), 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) and p-values were calculated with statistical significance level set at p-value < 0.05 [34]. All variables in the model were assessed for collinearity, which was considered present if the variables had a variance inflation factor (VIF) greater than 3. Sensitivity analysis was done with 8 or more ANC contacts as the outcome.

Results

A total of 6,302 women were included in the analysis (Table 2). Majority of the women resided in rural areas (82.2%), had primary education (64.6%), had no exposure to newspapers (80.5%), no internet access (89.3%), had health insurance (81.1%), were married (80.8%) and were working (75.7%). Out of the 6,302 women, 3,696 (60%, 95% CI: 58.6–61.1) initiated ANC within the first trimester, 2,975 (47.2%, 95% CI: 46.1–48.6) had 4 or more ANC contacts, 16 (0.3%, 95% CI: 0.1–0.4) had 8 or more ANC contacts and 825 (13.1%, 95% CI: 12.4–14.1) utilized all the ANC components (good quality ANC). Details of the ANC components are shown in Table 3.

Factors associated with utilization of all ANC components

Exposure to newspapers/magazines at least once a week (aOR 1.48, 95% CI: 1.09–2.02), lower parity (para1: aOR 6.04, 95% CI: 3.82–9.57), having been visited by a field worker (aOR 1.47, 95% CI: 1.23–1.76) and belonging to smaller households (aOR 1.34, 95% CI: 1.10–1.63) were associated with more odds of utilizing all ANC components. Furthermore, initiating ANC in the first trimester (aOR 1.45, 95% CI: 1.18–1.79) and having had 4 or more ANC contacts (aOR 1.52, 95% CI: 1.25–1.85) were associated with more odds of utilizing all ANC components. Working women had lower odds of utilizing all ANC components (aOR 0.79, 95% CI: 0.66–0.95) as shown in Table 4. Factors associated with secondary outcomes (timing of ANC initiation and ANC frequency) are shown in supplementary file 2.

Discussion

In this study, only one in ten women in Rwanda reported to have experienced good quality ANC. Of these, two thirds had initiated ANC within the first trimester, about half had 4 or more ANC contacts, and less than one percent had 8 or more ANC contacts. Exposure to newspapers/magazines, parity, being visited by a fieldworker, working status, household size, timing of first ANC visit, and frequency of ANC visits were associated with utilization of all components of ANC.

Although still very low, at 13.1%, this proportion of women who utilized all ANC components in Rwanda represents a significant increase from the 1.9% of the 2015 RDHS [12]. It is slightly higher than the East African region prevalence of 11% [13]. In 2019, Benova et al., analyzed DHS data from 10 LMICs’s, which showed that Rwanda’s current proportion of women receiving all ANC components is higher than Nigeria’s (6.7%), close to that of Democratic Republic of Congo (12.6%) and lower than that of Zambia (21.8%) [12]. However, the proportion is similar to that observed in a study based on Cameroon's most recent DHS data (13.5%) [26]. Although components such as having a blood sample taken, blood pressure measured, urine sample taken and receiving iron tablets/syrups were utilized by over 80% of the women (95.5%, 87.4%, 82.6% and 80.6% respectively), having at least two tetanus injections (33.6%) and receiving drugs for intestinal parasites (43%) were highly underutilized. A similar pattern of low tetanus toxoid vaccine among pregnant women has been registered in the East African region (50.4%) [35] and in The Gambia (34.8%) [36]. More efforts such as awareness and sensitization to women and increasing availability of immunization logistics and human resources are needed to ensure increased uptake.

Women visited by a fieldworker, were more likely to receive adequate ANC services compared to their counterparts that were not visited. Rwanda has a strong community health based programme as the lowest unit of its national health system [24]. Maternal health community health workers (CHWs) provide the first point of contact health services for most women seeking care [37]. Through a male–female CHW pair,women are able to receive the first line maternal and newborn health services within their own communities [20]. These CHWs ensure easier and equitable access to maternal care especially in hard-to-reach areas where health facilities are located far from the beneficiaries [37]. Interaction with field health workers has been documented to be associated with better maternal healthcare utilisation [37, 38]. This may be possible due to the counselling and information on key themes including the use of antenatal services, linkages to other reproductive health services, behavior change and delivery in health facilities [39, 40]. Furthermore, maternal health CHWs promote timely maternal health care seeking, document and follow up ANC appointments, promote male involvement in maternal health utilization and provide timely maternal health reports to their respective health centres with vital statistics such as number of pregnant women they have in their village, their ANC appointments and due dates [37, 41].

In this study, initiating ANC in the first trimester and attending ANC four or more times was associated with higher odds of receiving all components of ANC during pregnancy. Relatedly, women who made less than four ANC visits had lower odds of reporting quality ANC compared to those that had four or more visits. This is consistent with evidence from previous studies [42,43,44]. Initiating ANC in the first trimester accords opportunities to get timely ANC counselling and more time to have several ANC contacts in the subsequent months hence increasing the odds of receiving all the necessary components of ANC care [5, 42, 44]. Women who obtain 4 or more ANC visits have more contact with healthcare providers which renders them more likely to receive extensive health education and the best possible care [45, 46]. Invariably, 4 or more ANC attendance is an indication of a woman’s consciousness and commitment to her wellbeing in pregnancy [6, 26]. Additionally, frequent contact between the skilled provider and the pregnant woman helps in the development of good rapport between the two, enhances women’s familiarity with the health system, builds trust and confidence in the services received [47]. All these motivate women to freely share information with the ANC providers thereby facilitating the process of receiving more ANC components or reporting positively [2, 47, 48]. This demonstrates that Rwanda maternal health stakeholders need to prioritize explorative research to understand barriers of utilizing the recommended ANC contacts. These findings can help inform policy to ensure effective implementation of the latest WHO ANC model which recommends at least eight contacts for every pregnancy, in order to increase the odds of utilizing ANC components [42].

In this study, utilization of all ANC components reduced markedly with increasing parity. The odds of receiving all ANC components were six times higher among women who had at least one child, and reduced by half to three times higher among those with two to four children, compared to those with five or more children. This finding is not surprising because it has been reported consistently by studies in Ethiopia [45, 49], Haiti [50], Nigeria [51], and in an analysis of combined DHS data of six East African countries [13]. This could be due to the fact that women with multiple parities have a lower desire to continue attending all the recommended ANC visits. Largely because of the erroneous belief that they might no longer be in need of those services as they already have experience with pregnancy and childbirth [45, 49]. Therefore, they are less anxious and perceive their risk to be very low [13]. It could also possibly be because high parity pregnancies are more likely to be unintended, which has been linked to the later timing and lower amount of antenatal visits and hence reduced likelihood of receiving complete ANC components [52]. The increased odds of receiving all ANC components associated with low parity could also partly be linked to the observed association between women belonging to smaller households and good quality ANC. Women who belonged to smaller households had higher odds of receiving all ANC components compared to those from larger households a finding that has been shown in other studies [7, 53]. This might be partly attributed to availability of more resources and time because of less house chores in the smaller households [7, 52]. Having time enables women to initiate ANC early and have frequent subsequent ANC contacts hence leading to increased likelihood of receiving all the needed ANC contacts.

Working women had lower odds of receiving all ANC components. This is contrary to the evidence that women who work have higher prospects of effective maternal healthcare utilisation because they are likely to have a wider social network and receive information from other women they meet at the work place [6, 54, 55]. This may present an opportunity for them to learn about quality ANC and its importance and hence demand for it during ANC visits, unlike those who do not work. Similar to our findings, working women have been shown to have lower odds of utilizing quality ANC and other maternal health services [39, 56]. A possible explanation for this finding of a negative association could be related to the fact that working women do not have time to attend ANC care because of unfavorable work-related schedules and pressures such as limited or no leave days, and long working hours [39, 56, 57]. Subsequently, such barriers hinder their ability to initiate ANC on time and adhere to the recommended schedule of at least eight ANC contacts.

Exposure to newspapers/magazines was associated with higher odds of receiving all ANC components. Previous studies have showed a positive association between exposure to mass media and maternal health utilisation including ANC [58,59,60,61]. Exposure to mass media leads to positive health seeking behavioral changes through sharing information about the benefits of timely and frequent ANC contacts [3, 58]. Through mass media, women are also able to get information on availability of services and the working hours of these health facilities [39, 58, 62]. Furthermore, women that have access to newspapers are usually literate with better education, which allows them to engage in heath literacy related discussions with others. These discussions have the potential to challenge unfavorable stereotypes that may affect health seeking behaviors [5, 63, 64].

Study strength and limitations

The study used a nationally representative dataset, making our findings generalizable to all women in Rwanda. In addition to considering the latest WHO ANC guidelines such as utilization of eight or more ANC contacts, the study used the most recent national data set with a large sample hence results are timely for policy makers to assess progress towards the global and national targets and implementation of the WHO ANC guidelines. However, the cross-sectional design doesn’t allow the establishment of causal relationships, but rather only associations. The use of self-reported answers without means of verification risked possibility of giving less accurate data. However, to mitigate this, data about the most recent birth was considered.

There was also a lack of data on other key determinants of adequate ANC such as male involvement and support, knowledge of ANC, the perceived quality/satisfaction of received care all of which could affect the uptake of ANC services and some health facility and health system determinants such as availability of medical supplies, waiting time etc. Lastly, the survey only included women with live births leaving out those with poor pregnancy outcomes such as still births.

Explorative qualitative research could be helpful in getting a deeper understanding why working women, those in Kigali and those belonging to larger households have lower odds of utilizing all ANC components. To enable comprehensive analysis of ANC and other maternal services in relation to the latest WHO guidelines, we recommend DHS to add more variables as per WHO guidelines recommendations such as use of ultrasound scan and specifying the timing and number of the ANC contacts in the different trimesters instead of just providing data on the timing of the first ANC contact. Furthermore, we recommend DHS to consider adding data on crucial factors such as male involvement and support, knowledge of ANC, the perceived quality/satisfaction of received care and some health facility and health system determinants such as availability of medical supplies, waiting time etc. or primary research that can incorporate the above factors.

Conclusion

In Rwanda, the proportion of women who utilize all ANC components has improved since the last DHS, but it is still very low. Among the ANC components, TT injection uptake is at 33.6% which is the lowest hence more efforts such as awareness and sensitization to women, more research to explore factors associated with this low utilization and increasing availability of immunization logistics and human resources are needed to ensure increased uptake. Ministry of Health programs need to capitalize on existing positive interventions to further increase their coverage such as supporting women to subscribe to health insurance schemes and strengthening the community health programme to enable more field health workers providing counseling and providing care. High parous, unmarried, poor, Kigali resident women from larger households should be targeted for these programmes and policies aimed at increasing utilisation of ANC.

Availability of data and materials

The data set used is openly available upon permission from MEASURE DHS website (URL: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm).

Abbreviations

- EA:

-

Enumeration area

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COR:

-

Crude Odds Ratio

- DHS:

-

Demographic Health Survey

- RDHS:

-

Rwanda Demographic Health Survey

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- PNC:

-

Postnatal care

- SBA:

-

Skilled Birth Attendance

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Science

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Marternal mortality. 2019. (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality).

Sserwanja Q, Mukunya D, Nabachenje P, Kemigisa A, Kiondo P, Wandabwa JN, Musaba MW. Continuum of care for maternal health in Uganda: A national cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2):e0264190.

Sserwanja Q, Mufumba I, Kamara K, Musaba MW. Rural–urban correlates of skilled birth attendance utilisation in Sierra Leone: evidence from the 2019 Sierra Leone Demographic Health Survey. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3): e056825.

World Health Organization. WHO Recommendation on Antenatal Care for Positive Pregnancy Experience. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

Sserwanja Q, Musaba MW, Mutisya LM, Olal E, Mukunya D. Continuum of maternity care in Zambia: a national representative survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):604.

Sserwanja Q, Nabbuye R, Kawuki J. Dimensions of women empowerment on access to antenatal care in Uganda: a further analysis of the Uganda demographic health survey. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2016;2022:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3439.

Okedo-Alex IN, Akamike IC, Ezeanosike OB, Uneke CJ. Determinants of antenatal care utilisation in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10): e031890.

Tunçalp Ӧ, Pena-Rosas JP, Lawrie T, Bucagu M, Oladapo OT, Portela A, Metin Gülmezoglu A. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience-going beyond survival. BJOG. 2017;124(6):860–2.

Musarandega R, Nyakura M, Machekano R, Pattinson R, Munjanja SP. Causes of maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of studies published from 2015 to 2020. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04048–04048.

Tiruye G, Shiferaw K, Shunu A, Sintayeu Y, Seid AM. Antenatal care predicts neonatal mortality in Eastern Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Neonatol. 2022;36(1):42–54.

Raru TB, Ayana GM, Zakaria HF, Merga BT. Association of higher educational attainment on antenatal care utilization among pregnant women in east africa using Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from 2010 to 2018: a multilevel analysis. Int J Women’s Health. 2022;14:67–77.

Benova L, Tunçalp Ö, Moran AC, Campbell OMR. Not just a number: examining coverage and content of antenatal care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(2): e000779.

Raru TB, Mamo Ayana G, Bahiru N, Deressa A, Alemu A, Birhanu A, Yuya M, Taye Merga B, Negash B, Letta S. Quality of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in East Africa using Demographic and Health Surveys: A multilevel analysis. Womens Health. 2022;18:17455065221076732.

Magge H, Chilengi R, Jackson EF, Wagenaar BH, Kante AM, Hingora A, Mboya D, Exavery A, Tani K, Manzi F, et al. Tackling the hard problems: implementation experience and lessons learned in newborn health from the African Health Initiative. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(3):829.

Magge H, Nahimana E, Mugunga JC, Nkikabahizi F, Tadiri E, Sayinzoga F, Manzi A, Nyishime M, Biziyaremye F, Iyer H, et al. The all babies count initiative: impact of a health system improvement approach on neonatal care and outcomes in Rwanda. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2020;8(3):000.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda - NISR, Ministry of Health - MOH, ICF. Rwanda demographic and health survey 2019–20. Kigali, Rwanda and Rockville: NISR/MOH/ICF; 2021.

de Masi S, Bucagu M, Tunçalp Ö, Peña-Rosas JP, Lawrie T, Oladapo OT, Gülmezoglu M. Integrated person-centered health care for all women during pregnancy: implementing world health organization recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(2):197–201.

Peet ED, Okeke EN. Utilization and quality: How the quality of care influences demand for obstetric care in Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0211500.

Hategeka C, Arsenault C, Kruk ME. Temporal trends in coverage, quality and equity of maternal and child health services in Rwanda, 2000–2015. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(11): e002768.

Sayinzoga F, Lundeen T, Gakwerere M, Manzi E, Nsaba YDU, Umuziga MP, Kalisa IR, Musange SF, Walker D. Use of a facilitated group process to design and implement a group antenatal and postnatal care program in Rwanda. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2018;63(5):593–601.

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Finance Mo, Economic Planning/Rwanda, Ministry of Health/Rwanda, ICF International. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2014–15. Kigali: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning/Rwanda, Ministry of Health/Rwanda, and ICF International; 2016.

Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Health. Health Sector Policy. Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Health: Kigali. 2015. http://www.moh.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/policies/Health_Sector_Policy___19th_January_2015.pdf. Accessed 31 Dec 2021.

Lu C, Chin B, Lewandowski JL, Basinga P, Hirschhorn LR, Hill K, Murray M, Binagwaho A. Towards universal health coverage: an evaluation of Rwanda Mutuelles in its first eight years. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39282–e39282.

Schurer JM, Fowler K, Rafferty E, Masimbi O, Muhire J, Rozanski O, Amuguni HJ. Equity for health delivery: opportunity costs and benefits among Community Health Workers in Rwanda. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9): e0236255.

Joshi C, Torvaldsen S, Hodgson R, Hayen A. Factors associated with the use and quality of antenatal care in Nepal: a population-based study using the demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):94.

Ameyaw EK, Dickson KS, Adde KS, Ezezika O. Do women empowerment indicators predict receipt of quality antenatal care in Cameroon? Evidence from a nationwide survey. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):343.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience Summary. Geneva: WHO; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Blackstone SR. Evaluating antenatal care in Liberia: evidence from the demographic and health survey. Women Health. 2019;59(10):1141–54.

Abrha S, Shiferaw S, Ahmed KY. Overweight and obesity and its socio-demographic correlates among urban Ethiopian women: evidence from the 2011 EDHS. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:636.

Dankwah E, Zeng W, Feng C, Kirychuk S, Farag M. The social determinants of health facility delivery in Ghana. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):101.

Agbadi P, Eunice TT. Complex samples logistic regression analysis of predictors of the current use of modern contraceptive among married or in-union women in Sierra Leone: Insight from the 2013 demographic and health survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231630.

Zou D, Lloyd J.E.V, Baumbusch J.L. Using SPSS to analyze complex survey data. A Primer J Modern Appl Stat Methods. 2019;18(1):eP3253. https://doi.org/10.22237/jmasm/1556670300.

Croft Trevor N, Aileen MJM, Courtney KA, et al. Guide to DHS Statistics. ICF: Rockville; 2018.

Sserwanja Q, Musaba MW, Mukunya D. Prevalence and factors associated with modern contraceptives utilization among female adolescents in Uganda. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):61.

Belay AT, Fenta SM, Agegn SB, Muluneh MW. Prevalence and risk factors associated with rural women’s protected against tetanus in East Africa: evidence from demographic and health surveys of ten East African countries. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3): e0265906.

Barrow A, Barrow S, Jobe A. Differentials in prevalence and correlates on uptake of tetanus toxoid and intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine during pregnancy: a community-based cross-sectional study in the Gambia. SAGE Open Med. 2022;10:20503121211065908.

Tuyisenge G, Crooks VA, Berry NS. Facilitating equitable community-level access to maternal health services: exploring the experiences of Rwanda’s community health workers. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2019;18(1):181.

Tuyisenge G, Hategeka C, Luginaah I, Cechetto DF, Rulisa S. “I cannot say no when a pregnant woman needs my support to get to the health centre”: involvement of community health workers in Rwanda’s maternal health. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):524.

Sserwanja Q, Nuwabaine L, Kamara K, Musaba MW. Prevalence and factors associated with utilisation of postnatal care in Sierra Leone: a 2019 national survey. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):102.

McMahon SA, Ho LS, Scott K, Brown H, Miller L, Ratnayake R, Ansumana R. “We and the nurses are now working with one voice”: How community leaders and health committee members describe their role in Sierra Leone’s Ebola response. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):495.

Tuyisenge G, Hategeka C. Mothers’ perceptions and experiences of using maternal health-care services in Rwanda. 2019;59(1):68–84.

Haile D, Habte A, Bogale B. Determinants of frequency and content of antenatal care in postnatal mothers in Arba Minch Zuria district, SNNPR, Ethiopia, 2019. Int J Women’s Health. 2020;12:953–64.

Bryce E, Katz J, Pema Lama T, Khatry SK, LeClerq SC, Munos M. Antenatal care processes in rural Southern Nepal: gaps in and quality of service provision—a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12): e056392.

Afulani PA. Rural/urban and socioeconomic differentials in quality of antenatal care in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2): e0117996.

Tadesse Berehe T, Modibia LM. Assessment of quality of antenatal care services and its determinant factors in public health facilities of Hossana Town, Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: a longitudinal study. Advances in Public Health. 2020;2020:5436324.

Majrooh MA, Hasnain S, Akram J, Siddiqui A, Memon ZA. Coverage and quality of antenatal care provided at primary health care facilities in the ‘Punjab’ Province of ‘Pakistan.’ PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11): e113390.

Kare AP, Gujo AB, Yote NY. Quality of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women attending government hospitals in Sidama Region. Southern Ethiopia SAGE Open Med. 2021;9:20503121211058056–20503121211058056.

Kassaw A, Debie A, Geberu DM. Quality of prenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women at public health facilities of Wogera District, Northwest Ethiopia. J Pregnancy. 2020;2020:9592124–9592124.

Muchie KF. Quality of antenatal care services and completion of four or more antenatal care visits in Ethiopia: a finding based on a demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):300.

Babalola SO. Factors associated with use of maternal health services in Haiti: a multilevel analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2014;36(1):1–9.

Emelumadu O, Ukegbu A, Ezeama N, Kanu O, Ifeadike C, Onyeonoro U. Socio-demographic determinants of maternal health-care service utilization among rural women in anambra state, South East Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(3):374–82.

Ali AAA, Osman MM, Abbaker AO, Adam I. Use of antenatal care services in Kassala, eastern Sudan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(1):67.

Sahito A, Fatmi Z. Inequities in antenatal care, and individual and environmental determinants of utilization at national and sub-national level in Pakistan: a multilevel analysis. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(8):699–710.

Asim M, Hameed W, Saleem S. Do empowered women receive better quality antenatal care in Pakistan? An analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1): e0262323.

Afulani PA, Buback L, Essandoh F, Kinyua J, Kirumbi L, Cohen CR. Quality of antenatal care and associated factors in a rural county in Kenya: an assessment of service provision and experience dimensions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):684.

El-Gilany AH, El-Wehady A, El-Hawary A. Maternal employment and maternity care in Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13(3):304–12.

Karl M, Schaber R, Kress V, Kopp M, Martini J, Weidner K, Garthus-Niegel S. Precarious working conditions and psychosocial work stress act as a risk factor for symptoms of postpartum depression during maternity leave: results from a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1505.

Sserwanja Q, Mutisya LM, Musaba MW. Exposure to different types of mass media and timing of antenatal care initiation: insights from the 2016 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):10.

Sserwanja Q, Mukunya D, Musaba MW, Kawuki J, Kitutu FE. Factors associated with health facility utilization during childbirth among 15 to 49-year-old women in Uganda: evidence from the Uganda demographic health survey 2016. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1160.

Regassa N. Antenatal and postnatal care service utilization in southern Ethiopia: a population-based study. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11(3):390–7.

Ekholuenetale M, Benebo FO, Idebolo AF. Individual-, household-, and community-level factors associated with eight or more antenatal care contacts in Nigeria: evidence from Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9): e0239855.

Tiruneh FN, Chuang K-Y, Chuang Y-C. Women’s autonomy and maternal healthcare service utilization in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):718.

Asp G, Pettersson KO, Sandberg J, Kabakyenga J, Agardh A. Associations between mass media exposure and birth preparedness among women in southwestern Uganda: a community-based survey. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):22904.

Bwalya BB, Mulenga MC, Mulenga JN. Factors associated with postnatal care for newborns in Zambia: analysis of the 2013–14 Zambia demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):418.

Acknowledgements

We thank the DHS program for making the data available for this study.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QS conceived the idea, drafted the manuscript, performed analysis, interpreted the results and drafted the subsequent versions of the manuscript. LN, GG, JNW and MWM drafted the manuscript, interpreted the results and drafted the subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The 2019–2020 RDHS ensured that all methods were carried out in accordance with national and international relevant guidelines and regulations. “The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Rwanda National Ethics Committee (RNEC) and the ICF Institutional Review Board”[16]. Furthermore, during data collection, local authorities’ permission and informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). Ethical approval ID was not provided in the RDHS survey report. Authors received written permission from DHS to access this dataset.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure 1.

Flow chat of sampling process.

Additional file 2.

Factors associated with ANC initiation timing and frequency as per RDHS 2019-20.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sserwanja, Q., Nuwabaine, L., Gatasi, G. et al. Factors associated with utilization of quality antenatal care: a secondary data analysis of Rwandan Demographic Health Survey 2020. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 812 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08169-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08169-x