Abstract

Background

The commitment of hospital managers plays a key role in decisions regarding investments in quality improvement (QI) and the implementation of quality improvement systems (QIS). With regard to the concept of social capital, successful cooperation and coordination among hospital management board members is strongly influenced by commonly shared values and mutual trust. The purpose of this study is to investigate the reliability and validity of a survey scale designed to assess Social Capital within hospital management boards (SOCAPO-B) in European hospitals.

Methods

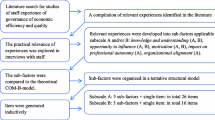

Data were collected as part of the EU funded mixed-method project “Deepening our understanding of quality improvement in Europe (DUQuE)” from 210 hospitals in 7 European countries (France, Poland, Czech Republic, Germany, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey). The Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) completed the SOCAPO-B scale (six-item survey, numeric scale, 1=‘strongly disagree’ to 4=‘strongly agree’) regarding their perceptions of social capital within the hospital management board. We investigated the factor structure of the social capital scale using exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, while construct validity was assessed through Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the scale items.

Results

A total of 188 hospitals participated in the DUQuE-study. Of these, 177 CEOs completed the questionnaire(172 observations for social capital) Hospital CEOs perceive relatively high social capital among hospital management boards (average SOCAPO-B mean of 3.2, SD = 0.61). The exploratory factor analysis resulted in a 1-factor-model with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91. Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the single scale items ranged from 0.48 to 0.68.

Conclusions

The SOCAPO-B−scale can be used to obtain reliable and valid measurements of social capital in European hospital management boards, at least from the CEO’s point of view. The brevity of the scale enables it to be a cost-effective and tool for measuring social capital in hospital management boards.

Trial registration

This validation study was not registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hospital quality management is still in its infancy but developing rapidly in response to new pressures and demands. Modern hospitals around the globe are faced with a range of complex challenges (financial, technological and population based). Improving the quality of care in such circumstances has become a critical issue for hospitals to grapple with around the globe. Hospitals in Europe have adapted their services to meet these challenges and are implementing a range of quality improvement (QI) strategies and attempt to improve the quality and safety of patient care including incident reporting systems, implementation of evidence-based guidelines, breakthrough projects, audits, and a variety of performance indicators and metrics. There are also increasing external pressure on hospitals to provide better, safer care to patients. As such, an increased importance of establishing quality improvements systems (QIS) within health care organizations has become a vital part of QI-strategies in hospitals. Nevertheless, the application of newly developed operational standards and guidelines, information and scientific results appears to advance only slowly and unevenly both within and across countries [1].

Investments in patient safety and the implementation of QIS are to a large extent based on the decisions of senior managers [2, 3]. Moreover, managers sitting at the apex of the organisation are responsible for setting strategic direction, crafting strategy and creating organizational cultures which support (or at least do not hinder QI-efforts [4]. Therefore, the quality of hospital managers leadership and decision-making is an important organizational capability for successfully implementing QI [4,5,6]. In highly fragmented systems such as health care organizations, achieving effective relationships based on trust is a major challenge. From the perspective of an individual hospital, such relationship building and performing has to be nurtured in the context of interprofessional teamworking and multi-hierarchical collaboration. Organization research has highlighted that supervision, standardization and mutual adjustment (informal communication and the ability to adapt to each other) are key mechanisms for a productive organisational culture [7]. Effective organizational relationship building is positively associated with better quality of care [8] and hospital profitability [9].

Social capital is a specific form of organizational resource. The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu conceives of social capital as network of relationships that allow access to resources. The amount of social capital is dependent on (1) grade of expansion regarding the social network, and (2) the volume of capital that can be accessed via the network [10]. According to Putnam [11], a deficit of social capital leads to inefficiency and hampers coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit [11]. A specific characteristic of social capital is that, in contrast to other forms of capital, the resource does not lie in the social actors themselves (such as human capital) or the physical means of production (physical capital), but rather in the structure of relationships [12]. According to Coleman closeness and trustworthiness of social structure are two essential prerequisites for enhancing social capital. That is, that when members of a collective perceive close relationships, they are more likely to help each other, to create effective procedures and share key information [12]. In Germany, the construct of social capital has been used, in a variety of forms for over 20 years to assess the quality and structure of relationships in organisations [13]. In healthcare organizations, social capital has a special significance being associated as it is with higher job satisfaction among clinicians [14], reduced ‘burnout’ among employees [15, 16], improved risk management [17] and better coordination [8]. Organizations with high levels of social capital are characterized by social relations between the members of an organization based on mutual trust and understanding as well as shared convictions and values [18]. Such cultures influence collective organisational endeavours and supports a specific understanding of patient safety and quality of care.

The quality of leadership depends on commonly shared values and mutual trust among hospital management board members. From a social capital perspective, these are essential requirements for successful cooperation and coordination within groups – including the hospital management board [19]. Although it has been used in several earlier studies, the social capital scale has not been intensively validated. An earlier study on employees’ social capital (SOCAPO-E) has recently been published [20]. In this study we focus on CEOs. The development of a brief scale consisting of six items was based on sociological principles relating to social capital described by Bourdieu [10], Coleman [21], Putnam [11, 22], and Fukuyama [23] and especially the concept of community [24]. The general social items of the SOCAPO-E [20] adapted to hospital management boards to measure the social capital within the board from the perspective of board members (SOCAPO-B). We incorporated this scale into the CEO’s questionnaire asking them about their perceptions regarding levels of social capital within the hospital (management) board (SOCAPO-B). Therefore, this study set out to investigate the reliability and validity of a survey scale to assess Social Capital within hospital management boards (SOCAPO-B) in hospitals in 7 European countries.

Methods

Setting, study design and population

This paper is based on data from the parent project “Deepening our understanding of QI-in Europe (DUQuE)” funded by the EU 7th Research Framework Program. More details on the study setting, population, and design have previously been published [25, 26]. DUQuE sought to study the effectiveness of QIS in European hospitals. The study used a multi-method approach to data collection and measurement. Overall, we approached 210 randomly selected hospitals in 7 countries (France, Poland, Germany, Czech Republic, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey). The sample was restricted to hospitals with more than 130 beds that provide for acute myocardial infection, stroke, hip fracture, and delivery. Data were collected at four levels (hospital level, departmental level, professional level, and patient level). However, the analyses presented in this article consists solely of hospital-level constructs measured within a survey for Chief Executive Officers (CEOs). Those were selected as key informants, since the CEOs are considered to have referent and informational power in the hospital and able to implement new structures, strategies and incentives to improve hospital performance. Data were collected through a web-based questionnaire between May 2011 and February 2012.

Measure: social capital of hospital management boards (SOCAPO-B)

The variable ‘social capital’ of management boards’ (SOCAPO-B) was devised to measure two key features of the construct 1) common values and 2) perceived mutual trust in organizations [18]. Originally, the six-item scale was developed to measure communal social capital of healthcare organizations out of the perspectives of employees (SOCAPO-E) [27]. The variable consisted of six items and has been used in several previous studies [5, 28,29,30,31]. The reliability of the social capital scale - tested in a prior German study - is high with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 [27]. Answers were scaled on a 4-point Likert scale (range from 1=‘strongly disagree’ to 4=‘strongly agree’). Higher values indicate that CEOs have a higher perception of social capital in the hospital management board. The six questions of the scale are: When thinking about your Hospital (Management) Board, how much do you agree with the following statements? (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = somewhat agree, 4 = strongly agree): Within our Hospital (Management) Board… (1) … there is unity and agreement, (2) … we trust one another, (3) … there is a “we feeling” among Board members, (4) … the work climate is good, (5) … the willingness to help one is great, (6) … we share many common values.

Translation and adaptation

To ensure comparability and interpretability of data in the cross-national contexts and to obtain practical implications, rigorous study standards regarding study design, translation processes, administration and country coordination must be upheld. In accordance with the recommendations of Guillemin et al. [32] single items from the original social capital scale were translated into English by three independent professional translators/native speakers. The following backwards translations into German were undertaken by another three professional translators/native speakers. Backwards translation has been independently reviewed and assessed by a team of researchers from the Institute of Medical Sociology, Health Services Research, and Rehabilitation Science. Based on this review, the most appropriate translations were selected. In the second step - again using a forward-backward method [32] - the SOCAPO-B-scale was translated together with all DUQuE-data collection tools and as part of the CEO’s questionnaire by the Country Coordinators – who were responsible for data collection in each country. Differences in language, cultures, contextual factors and differences in organisations settings within the countries have been taken into consideration [33, 34].

Statistical analyses

Before embarking on the in-depth analysis, respondents with missing values of > 30 % in social capital items were excluded because of poor data quality. The final dataset used in this analysis contains only hospitals with complete records on all six social capital items.

First, we used descriptive statistics to describe the sample data used for this analysis. For categorical variables we calculated frequencies and percentages. For continuous variables, we calculated the minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation. For sampling adequacy, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Measure of Sample Adequacy (MSA) coefficients have been calculated. Values of > 0.60 indicate a good applicability and values of > 0.90 would indicate a perfect applicability [35].

Prior to undertaking factor analyses, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients for all 6 social capital items (inter-item correlation) and between items and SOCAPO-B-scale (item-total correlation). According to Campbell and Fiske [36], we determined a cut-off value of ≥ 0.70 for inter-item correlation. Higher values indicate that the items measure the same concepts, while values < 0.30 indicate a poor relationship between the single items [35]. Additionally, we examined the homogeneity of SOCAPO-B-scale using item-total correlations. Coefficients of ≥ 0.40 would indicate adequate evidence of scale homogeneity. This analysis was followed by a principal component analysis (PCA) in order to study the component structure of the SOCAPO-B-scale. We set eigenvalues above 1.0 and used Varimax rotation to optimize factor structure [35]. Cut-off value for factor loadings was set to 0.4 to minimize item cross-loadings [35].

During the next stage we performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) [37] to test whether the original developed factor structure of the SOCAPO-B-scale fitted our data. In accordance with Kline [37] and Hair et al. [38] we used global and local fit indices for assessing the appropriateness of the model. Goodness-of-fit was assessed with the Chi-squared values indicating differences in observed and expected covariance matrices [37, 38]. Since Chi-squared value is sensitive to the sample size, we calculated the normed Chi-squared value (Chi²/df) setting a cut-off value of ≤ 2.5 [39]. We also computed the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) as absolute model fit measure with recommended cut off value of > 0.90 [38]. Additionally, we assessed several incremental and descriptive measures of model fit: (1) Comparative Fit Index (CFI); (2) Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI); (3) Bentler-Bonett Non-normed Index (NNFI); (4) Adjusted Goodness od Fit Index (AGFI); (5) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Because the Standardised Root Mean Residual (SRMR) might be biased with less than 12 observed variables [38], we refrained from calculating this measure. With a sample size of N less than 250 and the number of observed variables less than 12, cut-off values were determined as follows: CFI, NNFI and AGFI ≥ 0.90, NFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA (with CFA ≥ 0.90) ≤ 0.07 [38,39,40]. In order to assess the degree to which the scale is reliable and valid we used local fit indices with the following criteria and cut-off values: Indicator reliability ≥ 0.30, factor reliability ≥ 0.60 and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) ≥ 0.50 [41].

Finally, the internal consistency (reliability) was examined through Cronbach’s alpha, which is a coefficient used to assess the interrelatedness of the items and the homogeneity of the scale”, and in addition underline the meaning of the values 0.70 and 0.90 that you have indicated [35, 37].

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Overall, 188 out of 210 hospitals (response rate = 89.5 %) participated in the DUQuE-study. Of these, we received 177 completed questionnaires from hospital CEOs. Due to missing values, we count 172 observations for social capital. The final dataset used for these analyses contains only hospitals with complete records on all SOCAPO-B-items (N = 172).

Characteristics of the hospitals used in this analysis are presented in Table 1. Almost 81.4 % (N = 140) of the hospitals were public hospitals, while 18.6 % (N = 32) were non-public hospitals. The sample included 42.4 % (N = 73) teaching hospitals and 57.6 % (N = 99) non-teaching hospitals. 18 hospitals (10.5 %) had < 200 beds, 74 hospitals (43.0 %) had 200–500 beds, 54 hospitals (31.4 %) had 501–1000 beds and 26 hospitals (15.1 %) had > 1000 beds.

The average mean of the SOCAPO-B-scale is 3.25 (SD = 0.61). The single items scores range between 3.10 (for board1) and 3.36 (for board4). The average mean of social capital per country (results not presented in a table) range from 3.02 (SD = 0.59) and 3.41 (SD = 0.61) (Table 1). The mean values for social capital (1 = ‘I strongly disagree’ and 4 = ‘I strongly agree’) show that hospital’s CEOs perceive a relatively high social capital within the hospital management board. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations for all SOCAPO-B-items and the SOCAPO-B-scale are presented in Table 2.

KMO coefficient value is 0.91, which indicates that the patterns of correlations are very compact and that a factor analysis is therefore appropriate for our data [35]. All SOCAPO-B-items reached superior MSA coefficients values of > 0.90 (range between 0.90 (board1) and 0.92 (board3)). Therefore, both the KMO test and the MSA test indicate that the data appropriately fit the criteria for factor analysis [35].

Factor analysis

Results on Inter-item and inter-total correlations are in Table 3. Inter-item correlation range between 0.48 (board1 and board6) and 0.68 (board2 and board4). Thus, all correlations reached acceptable values between 0.20 and 0.70. Item-total correlations range from 0.80 to 0.86 indicating sufficient scale homogeneity.

PCA resulted in 1 component with eigenvalue greater 1.0 supporting the assumption of a single factor structure for SOCAPO-B-scale. This one factor explains a total variance of 68.45. Rotating factor structure was not required. However, items load high on the extracted component with a range between 0.79 and 0.87 (Table 5).

Results from CFA indicated that the assumed factor structure fits the data for DUQuE’s CEOs. The factor model exhibited an acceptable-to-good global data fit (Table 4). Furthermore, the local fit indices were considered acceptable (Table 5). Regarding the indicator reliability all items exceeded the acceptable values. Moreover, the SOCAPO-B-scale reached the recommended critical values for the factor reliability and reached an adequate AVE value. These results suggested good convergent validity.

Overall Cronbach’s alpha reached a value of 0.91, above the recommended cut-off of 0.90 suggesting a close relation between single items. Dropping any single items would lead to an increase in Cronbach’s alpha.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to examine the psychometric properties of a theory-driven questionnaire measuring social capital among senior managers / hospital management boards in hospitals. The tests of the construct validity indicate that the SOCAPO-B-scale is a valid and reliable method of measuring social capital in European hospital management boards from the CEO’s point of view. Except for Cronbach’s Alpha exceeding minimal the suggested cut-off value of 0.90, results showed an acceptable level of reliability for SOCAPO-B. Based on the average mean of the SOCAPO-B-scale of 3.25 (SD = 0.61), we conclude that hospital’s CEOs perceive a relatively high social capital within the hospital management board.

Although the scale has been used in Germany for over 20 years, only a recent study published its psychometric properties based on employees’ data (SOCAPO-E) embedded in a German survey [20]. Our data were collected as part of the large scale European DUQuE-study on the effectiveness of QIS of hospitals. We believe this to be the first comprehensive study of QIS with an a priori development of a coherent theory to direct data collection and analysis, the variety of 7 European countries and the amount of standardized data [42]. Another major strength of the study is the high response rates of 89.5 %. Asking key informants may improve the understanding of organizational processes and management decisions made. They provide aggregated organizational data by reporting organizational and group properties rather than personal attitudes and behavior [43, 44]. A major limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study design which does not allow for causal conclusions nor conclusions about the sensitivity of change in the scale. Repeated measurements could have further supported the validity of the scale. Furthermore, we cannot be sure that the SOCAPO-B-scale structure is stable in all countries. Especially, the unequally distributed numbers of participating hospitals per country, may have influenced the results. We believe that the general rationale of the validation is independent of country effects and hope that future studies will show to what point the scale is also applicable in other regions. Psychometric testing in future assessments in similar settings would also help to confirm the results. Within the scope of this study, we were not able to examine any relationships between social capital and hospital management outcomes, but this has been conducted and published elsewhere [45]. That the social capital scale was embedded in a larger questionnaire within the DUQuE-study could have influenced the responses of the CEO’s. However, we assumed that the length of the questionnaire would not necessarily affect the validity or reliability of the SOCAPO-B-scale. There is an ongoing discussion, whether scale with even or odd numbers of options should be favored. Particularly for new constructs, to yield a forced tendency may be of advantage, since a middle category may be used as “I do not know” category with ambiguity about the respondent meant indifference or being torn between the different dimensions. Unmotivated respondents may reduce their cognitive effort by selecting the middle category as a consequence of satisficing [46]. Nonetheless, further analyses on validity and reliability should be performed using the SOCAPO-B questionnaire only. A further limitation is that questioning key informants can result in inaccurate or biased data, because informants are either motivated or not to do so [47]. Also, the views of CEOs may vary from front line staff or mid-tier executives lower down the organizational hierarchy. Future studies could explore these possible differences.

A small number of studies already suggest a vital role of social capital as a resource in health care organizations [28, 45]. Relevant processes encompass quality and risk management or strengthening patient-physician relationships. The fact that social capital is associated with work engagement, well-being and depressive symptoms among staff underlines its significance for general health and overall performance in health care organizations [20]. Recent social and economic changes in analyzed countries may be considered in future studies. Although social climate is an important asset in hospital quality development, it has not received much attention, in the literature. The brevity of the scale allows to include this important aspect in wider surveys on other areas of health services research (patient safety, general quality improvement, employees’ satisfaction, patients’ satisfaction).

Strengths and limitations of this study

From the management perspective, it is necessary to assess how the senior management of a hospital (especially the CEOs), assesses social capital within the management board, as they provide aggregated organizational data by reporting organizational and group properties rather than personal attitudes and behavior. We believe this to be the first comprehensive study of QIS using an a priori development of a coherent theory to direct data collection and analysis, the variety of 7 European countries and the amount of standardized data with high response rates of 89.5 %. Based on the positive results regarding the construct validity and an acceptable reliability for the social capital scale within the hospital management board, we recommend the use of this tool in future research. A major limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study design which does not allow for conclusions about causality or the sensitivity of change in the scale.

Conclusions

Decisions regarding investments in QI-and the implementation of QIS are based largely on the commitment of hospital management. Managers set the strategic direction of the organization, craft organisational strategy and guide efforts towards successful quality improvement. Mutual trust and shared values substantially influence the quality of cooperation, communication and ability to act as an organizational group. Therefore, we believe that the assessment of commonly shared values and mutual trust can support the implementation of QIS. Based on our findings regarding validity and reliability, we can recommend the SOCAPO-B-scale for the future assessment of social capital in hospital management boards. Finally, future studies in this area would benefit from examining social capital lower down the hierarchy, at the departmental, ward and team level.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the study group on reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AGFI:

-

Adjusted Goodness od Fit Index

- AVE:

-

Average Variance Extracted

- CEO:

-

chief executive officer

- CFA:

-

confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI:

-

Comparative Fit Index

- DUQuE:

-

“Deepening our understanding of quality improvement in Europe”

- GFI:

-

Goodness of Fit Index

- KMO:

-

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

- MSA:

-

Measure of Sample Adequacy

- NFI:

-

Normed Fit Index

- NNFI:

-

Non-normed Index

- QI:

-

Quality improvement

- QIS:

-

Quality improvement systems

- SOCAPO-B:

-

social capital within hospital management boards

- SOCAPO-E:

-

social capital of healthcare organizations out of the perspectives of employees

- SRMR:

-

Standardised Root Mean Residual

- RMSEA:

-

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

References

Schneider EC. Hospital quality management: a shape-shifting cornerstone in the foundation for high-quality health care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26 Suppl 1:1.

Colla JB, Bracken AC, Kinney LM, Weeks WB. Measuring patient safety climate: a review of surveys. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(5):364–6.

Flin R. Measuring safety culture in healthcare: A case for accurate diagnosis. Safety Science. 2007;45(6):653–7.

Glickman SW, Baggett KA, Krubert CG, Peterson ED, Schulman KA. Promoting quality: the health-care organization from a management perspective. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):341–8.

Hammer A, Ommen O, Rottger J, Pfaff H. The relationship between transformational leadership and social capital in hospitals–a survey of medical directors of all German hospitals. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012;18(2):175–80.

McFadden KL, Henagan S.C., Gowen III C.R. The patient safety chain: Transformational leadership’s effect on patient safety culture, initiatives, and outcomes. JOM. 2009;27(5):390–404.

Mintzberg H. Structures in five. Designing effective organizations.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.; 1993.

Gloede TD, Hammer A, Ommen O, Ernstmann N, Pfaff H. Is social capital as perceived by the medical director associated with coordination among hospital staff? A nationwide survey in German hospitals. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(2):171–6.

Gloede TD, Pulm J., Hammer, A., Ommen, O., Kowalski, C., Groß, S., Pfaff H. Interorganizational relationships and hospital financial performance: a resource-based perspective. The Service Industries Journal. 2013.

Bourdieu P. Ökonomisches Kapital, kulturelles Kapital, soziales Kapital. Soziale Ungleichheiten Sonderband 2 der Sozialen Welt. Göttingen: Kreckel, R.; 1983. p. 183–98.

Putnam RD. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy. 1995(6):65–78.

Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology,. 1988;94:95–120.

Badura B, Greiner, W., Rixgens, P., Ueberle, M., Behr., M. Sozialkapital.Grundlagen von Gesundheit und Unternehmenserfolg. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2008.

Ommen O, Driller E, Kohler T, Kowalski C, Ernstmann N, Neumann M, et al. The relationship between social capital in hospitals and physician job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:81.

Driller E, Ommen O, Kowalski C, Ernstmann N, Pfaff H. The relationship between social capital in hospitals and emotional exhaustion in clinicians: a study in four German hospitals. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(6):604–9.

Kowalski C, Ommen O, Driller E, Ernstmann N, Wirtz MA, Kohler T, et al. Burnout in nurses - the relationship between social capital in hospitals and emotional exhaustion. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(11–12):1654–63.

Ernstmann N, Ommen O, Driller E, Kowalski C, Neumann M, Bartholomeyczik S, et al. Social capital and risk management in nursing. J Nurs Care Qual. 2009;24(4):340–7.

Pfaff HB, Pühlhofer, et al. Das Sozialkapital der Krankenhäuser - wie es gemessen und gestärkt werden kann. In: Badura B, Schellschmidt, H., Vetter, C. Fehlzeiten-Report 2004: Gesundheitsmanagement in Krankenhäusern und Pflegeeinrichtungen; Zahlen, Daten, Analysen aus allen Branchen der Wirtschaft. Berlin: Springer; 2005. p. 81–109.

Putnam R. Social Capital Measuement and Consequences. isuma 2001. 2001:41–51.

Ansmann L, Hower KI, Wirtz MA, Kowalski C, Ernstmann N, McKee L, et al. Measuring social capital of healthcare organizations reported by employees for creating positive workplaces - validation of the SOCAPO-E instrument. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):272.

Coleman JS. Social Capital Foundation of Social Theory: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press 1990. p. 300–21.

Putnam RD. The prosperous community: social capital and public life. The American Prospect. 1993(13):35–42.

Fukuyama F. Social capital, civil society and development. Third World Q. 2001;22(1):7–20.

Calhoun C. Community. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013.

Groene O, Klazinga N, Wagner C, Arah OA, Thompson A, Bruneau C, et al. Investigating organizational quality improvement systems, patient empowerment, organizational culture, professional involvement and the quality of care in European hospitals: the ‘Deepening our Understanding of Quality Improvement in Europe (DUQuE)’ project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:281.

Secanell M, Groene O, Arah OA, Lopez MA, Kutryba B, Pfaff H, et al. Deepening our understanding of quality improvement in Europe (DUQuE): overview of a study of hospital quality management in seven countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26 Suppl 1:5–15.

Pfaff H, Pühlhofer, F., Brinkmann, A., et al. Der Mitarbeiterkennzahlenbogen (MIKE): Kompendium valider Kennzahlen. Köln: Klinikum der Univ. zu Köln, Inst. und Poliklinik für Arbeitsmedizin, Sozialmedizin und Sozialhygiene, Abt. Med. Soziologie; 2004.

Ernstmann N, Driller, E., Kowalski, C., et al. Social capital and quality emphasis: A cross-sectional multicenter study in German hospitals. International Journal of Healthcare Management 2012;5(2):98–103.

Lehner BS, Driller, E., Ansmann, L., et al. Does social capital influence work engagement? The case of hospital physicians in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Health inequalities over the life course: Joint congress of the ESHMS and DGMS 2012.

Pfaff H, Nitzsche, A., Jung, J., et al. Organizational social capital, personality and emotional exhaustion in hospital employees: a multilevel approach. American Public Health Association2012.

Pfaff H, Braithwaite J. A Parsonian Approach to Patient Safety: Transformational Leadership and Social Capital as Preconditions for Clinical Risk Management-the GI Factor. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11).

Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(12):1417–32.

Harkness J. Questionnaire Translation in Comparative Research. In: Harkness J, editor. Cross- Cultural Survey Methods. New Work: Wiley; 2003. p. 35–56.

Lynn P. Developing quality standards for cross-national survey research: five approaches. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2013;6(4):323–36.

Field AP. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: And sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publ.; 2013.

Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol Bull. 1959;56(2):81–105.

Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Hair JF, Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. et al. Multivariate data analysis: Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2010.

Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989.

Hu L-T, Bentler P. M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55.

Zwingmann C, Wirtz M, Muller C, Korber J, Murken S. Positive and negative religious coping in German breast cancer patients. J Behav Med. 2006;29(6):533–47.

Groene O, Sunol R, Consortium DUP. The investigators reflect: what we have learned from the Deepening our Understanding of Quality Improvement in Europe (DUQuE) study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26 Suppl 1:2–4.

Phillips LW. Assessing Measurement Error in Key Informant Reports: A Methodological Note on Organizational Analysis in Marketing. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(4):395.

Seidler J. On Using Informants: A Technique for Collecting Quantitative Data and Controlling Measurement Error in Organization Analysis. American Sociological Review. 1974;39(6):816.

Hammer A, Arah OA, Dersarkissian M, Thompson CA, Mannion R, Wagner C, et al. The relationship between social capital and quality management systems in European hospitals: a quantitative study. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e85662.

Bogner K, Landrock, U. Antworttendenzen in standardisierten Umfragen. Mannheim, GESIS – Leibniz Institut für Sozialwissenschaften (SDM Survey Guidelines). 2015.

Huber GP, Power, D. J. Retrospective reports of strategic-level managers: Guidelines for increasing their accuracy. Strat Magmt J. 1985;6(2):171–80.

Acknowledgements

The DUQuE indicators were critically reviewed by independent parties before their implementation. The following individual experts critically assessed the proposed indicators: Dr. J. Loeb, The Joint Commission (All four areas), Dr. S. Weinbrenner, Germany Agency for Quality in Medicine (All four areas), Dr. V. Mohr, Medical Scapes GmbH & Co. KG, Germany (All four areas), Dr. V. Kazandjian, Centre for Performance Sciences (All four areas), Dr. A. Bourek, University Center for Healthcare Quality, Czech Republic (Delivery). In addition, in France a team reviewed the indicators on myocardial infarction and stroke. This review combined the Haute Autorité de la Santé (HAS) methodological expertise on health assessment and the HAS neuro cardiovascular platform scientific and clinical practice expertise. We would like to thank the following reviewers from the HAS team: L. Banaei-Bouchareb, Pilot Programme-Clinical Impact department, HAS, N. Danchin, SFC, French cardiology scientific society, Past President, J.M. Davy, SFC, French cardiology scientific society, A.Dellinger, SFC, French cardiology scientific society, (A) Desplanques-Leperre, Head of Pilot Programme-Clinical Impact department, HAS, J.L.Ducassé, CFMU, French Emergency Medicine-learned and scientific society, practices assessment, President, M. Erbault, Pilot Programme-Clinical Impact department, HAS, Y. L’Hermitte, Emergency doctor, HAS technical advisor, (B) Nemitz, SFMU, French Emergency Medicine scientific societyB. Nemitz, SFMU, French Emergency Medicine scientific society, F. Schiele, SFC, French cardiology scientific society, (C) Ziccarelli, CNPC French cardiology learned society, M. Zuber, SFNV, Neurovascular Medicine scientific and learned society, President. We also invited the following five specialist organization to review the indicators: European Midwifes Association, European Board and College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, European Stroke Organisation, European Orthopaedic Research Society, European Society of Cardiology.

We thank the experts of the project for their valuable advices, country coordinators for enabling the field test and data collection, providing feedback on importance, metrics and feasibility of the proposed indicators, hospital coordinators to facilitate all data and the respondents for their effort and time to take part in the study.

Funding

The study “Deepening our Understanding of Quality Improvement in Europe (DUQuE) was supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP//2007–2013) under grant agreement no. 241822. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AH drafted the manuscript, contributed to the conception and design of the work, performed the analysis and the interpretation of the data. OAA, RM, OG, RS and HP contributed to the conception and design of the work, participated in the collection and interpretation of the data. KC contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data for the work and drafted parts of the article. All authors critically revised the article and gave final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

DUQuE fulfills all the requirements for research projects in the 7th framework of EU DG. Ethical approval was obtained also by the project coordinator at the Bioethics Committee of the Health Department of the Government of Catalonia, Spain. National legislation or standards of practice available in each country regarding confidentiality were complied with. The study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained by all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Prof. Holger Pfaff is a member of the editorial board of BMC Health Services Research. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hammer, A., Arah, O.A., Mannion, R. et al. Measuring social capital of hospital management boards in European hospitals: A validation study on psychometric properties of a questionnaire for Chief Executive Officers. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 1036 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07067-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07067-y