Abstract

Background

In many countries health policy encourages patients to choose their hospital, preferably by considering information of performance reports. Previous studies on hospital choice mainly have focused on patients undergoing elective surgery. This study examined a representative sample of hospital inpatients across disciplines and treatment interventions in Germany. Its research questions were: How many patients decide where to go for hospital treatment? How much time do patients have before admission? Which sources of information do they use, and which criteria are relevant to their decision?

Methods

Cross-sectional observational study covering 1925 inpatients of 46 departments at 17 hospitals in 2012. The stratified survey comprised 11 medical disciplines (internal medicine, gynaecology, obstetrics, paediatrics, psychiatry, orthopaedics, neurology, urology, ENT and geriatrics) on 3 hospital care levels representing 91.9% of all hospital admissions to inpatient care in Germany in 2012. The statistical analysis calculated the frequency distributions and 95% confidence intervals of characteristics related to the hospital choice.

Results

63.0% [60.9–65.2] of patients in Germany chose the hospital themselves, but only 21.1% [19.3–22.9] had more than one week to decide prior to admission. Major sources of information were personal knowledge of hospitals, relatives, outpatient health professionals and the Internet. Main criteria for the decision were personal experience with a hospital, recommendations from relatives and providers of outpatient services, a hospital’s reputation and distance from home. Specific quality information as provided by performance reports were of secondary importance.

Conclusions

A majority of patients in the German health system choose their hospital freely. Providers of outpatient health care can have an important “agent” function in the quality-oriented hospital choice especially for patients with little time prior to admission and those who do not decide themselves. Hospitals have an impact on patients’ future hospital choices by the treatment experience they provide to patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Free choice of healthcare providers, especially of hospitals, is a declared health policy objective in many countries and in Germany as well [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The reasons to promote free provider choice are diverse. In market-oriented health systems, like in the USA, free choice of healthcare providers is considered a competitive mechanism that improves quality and reduces costs [3, 4, 7]. Tax-funded and social security health systems expect a steering effect on the number of healthcare providers and the range of services offered, ultimately reducing waiting times and improving outcomes. [8,9,10,11]. Across health care systems, the free choice of healthcare providers constitutes an important element of patient autonomy. A more active role of patients in treatment processes is intended to improve therapy compliance and thereby outcomes [12,13,14,15], and promotes patient orientation as an independent quality dimension in health care [16, 17].

In Germany approximately 2000 hospitals with some 500,000 beds provide hospital care [rehabilitation clinics not included] with the hospitalist model as the standard provision of medical care for inpatients. They treat about 19 million inpatient cases with statutory and private insurance coverage per year [18]. About 88% of the 81 million inhabitants in Germany have statutory health insurance, and 11% are privately insured. A guideline of the Federal Joint Committee stipulates the hospital admission procedure for inpatients [19]. The Federal Joint Committee is the highest decision-making body of the joint self-government of physicians, dentists, hospitals and health insurance funds in the German health care system. Its respective guideline states that the indication for hospital treatment comes from outpatient doctors and is confirmed by the hospital physicians upon admission. The referring physician specifies “the two nearest reachable suitable hospitals …in appropriate cases” on the referral order [19]. In practice, however, patients are free in their choice of a hospital, encouraged by guides on patient rights as published by the Ministry of Health. Furthermore, in Germany patients are not registered with a specific hospital in their community, nor are primary care practitioners [54,000 in 2015] or specialised physicians in the ambulatory setting [94,000 in 2015] obliged to transfer a patient to a specific hospital. In Germany outpatient care is still provided mainly by medical specialists in their own practice in the ambulatory care setting. That is the reason for the hospitalist being the standard care model in hospitals. Thus the ambulatory care physician, who indicates hospital admission, is not an agent on behalf of a hospital. Some integrated care models provide a tight connexion with a specific hospital, especially with hospital owned policlinics, but patients are free to inscribe in such models with mostly a 12-month term of notice. Until now, though, very few patients are under these terms. For the sickness funds a free choice of hospitals does hardly imply different costs since diagnosis related groups were introduced in 2004 as reimbursement scheme for hospital treatments all over Germany with only minor differences between the 16 Laender. But it might occur that a patient is required to pay the transport to a distant hospital.

Informed decision is considered a core requirement for the free choice of healthcare providers. For this purpose, information on hospitals needs to be publicly available and known, easily accessible, comparable, structured and standardised. As to content, it should comprise scientifically validated and relevant quality indicators and be easily understandable in terms of language, scope and level of aggregation [20,21,22,23,24,25]. In Germany all hospitals have to publish obligatory quality reports whose structure and format is defined by the Federal Joint Committee. The reports are supposed to serve patients’ informed decision making when choosing a hospital and are freely available via Internet [26]. Numerous studies have analysed the significance of such performance information for patients and find it rather limited [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Although patient surveys have revealed much interest in quality information, it plays a minor role in the decision-making process even for elective interventions, and even if patients know and understand the quality information. Faber and colleagues [31] conclude that patient behaviour in this respect does not correspond to the model of market-oriented consumer choice, and Marshall and McLoughlin refer to the knowledge construction model supported by psychological and sociological studies as more relevant for patients’ decisions making in the healthcare context [33].

Studies on hospital choice have focused so far especially on two aspects: first, which criteria are important in the choice of a hospital from the patient perspective, and second, which sources of information do patients use. Numerous studies explore these two aspects [9, 22, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51], using various populations in qualitative, quantitative or experimental study designs. The selection lists for decision criteria and sources of information differ in terms of numbers, content, classification and assessment scale. A validated survey instrument for hospital choice does not yet exist. Due to this heterogeneity, the results of the above-mentioned studies are of limited comparable value.

Surveys reveal differences, however, depending on whether members of the general public or insured individuals who are mainly healthy and not required to choose a hospital were interviewed as “potential” patients [34,35,36,37], or whether respondents were patients before admission or after discharge from hospital treatment [9, 22, 27,28,29, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

A lot of surveys in Germany address the general population or persons with health insurance. The important criteria for their hypothetical hospital choice are: qualification of medical and nursing staff, hospital specialisation, detailed data on hygiene, interventions, outcomes and patient involvement. They quote their own outpatient care providers, information material, health insurers/sickness funds and patient counselling offices as the main sources of information [34,35,36,37]. Surveys interviewing patients find as the most important decision criteria: personal experience with hospitals, recommendations from outpatient care providers and relatives, the hospital’s reputation, distance from home and ease of access, but also aspects of the patient-caregiver relation such as degree of participation, sufficient time for conversation, or friendliness of staff, and in some health care systems the waiting time and whether a hospital has a supply contract with the patient’s health insurer. Main sources of information for patients are their own experience with a hospital, outpatient caregivers and relatives [9, 22, 27,28,29, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

These previous studies exploring patients’ hospital choice have mainly surveyed groups of patients undergoing elective hospital interventions with a longer period prior to the intervention, such as orthopaedic or general surgery, or cardiac or vascular surgery. There is a lack of studies analysing patient behaviour in choosing a hospital in day-to-day practice, across disciplines, type of intervention and level of care, including the time that remains to patients prior to admission. Furthermore, it is not known how many patients actually can choose their hospital. Against this background, our study explored four research questions on hospital choice from the patient perspective in the German health system:

-

1.

How many patients decide where to go for hospital treatment?

-

2.

How much time passes from indication for hospitalisation to admission?

-

3.

Which sources of information on hospitals do patients use prior to hospitalisation?

-

4.

Which criteria are of relevance to patients in choosing a hospital?

Methods

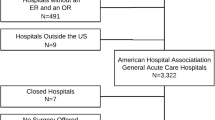

This survey is an observational cross-sectional study, based on quantitative primary data collected in a multi-centric study via questionnaire among inpatients in Germany. The population to which the study refers comprises all patients admitted for inpatient care to German hospitals in 2012 [18]. The sample was a disproportionally stratified random sample with an average of about 50 patients admitted consecutively for inpatient care in 46 departments of 17 hospitals in a total of 15 cities and towns situated in 5 different urban and rural regions in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW). NRW is the most populated federal state with 17.6 million citizens, i.e. 22% of Germany’s population. Hospitals were selected on the basis of regional differences and the level of care and contacted with the request to participate.

Stratification criteria are the medical discipline and the level of care. 11 medical disciplines with considerable patient intake (internal medicine, gynaecology, obstetrics, paediatrics, psychiatry, orthopaedics, neurology, urology, ENT and geriatrics) have been considered in the sample. In the year of data collection in 2012 these disciplines covered 17.1 million (91.9%) of the total of 18.6 million hospital admissions to inpatient care in Germany. Disciplines not part of the sample and covering some 8.1% of all inpatients in Germany are for example ophthalmology, dermatology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, neurosurgery, and nuclear medicine.

The stratification criterion “level of care” considers 3 care levels, defined according to number of beds: standard care (hospitals with less than 200 beds), specialist care (hospitals with 200–499 beds) and maximum care (hospitals with more than 499 beds). At the level of specialist and maximum care the sample covered two hospital departments for each discipline in different hospitals. ENT as the only exception has been considered at the maximum care level only since this discipline with lower case numbers is mainly covered by affiliated doctors at the specialist care level. The standard care level comprises internal medicine and surgery. Two hospital departments of each discipline from different hospitals formed part of the sample. In order to compare the realised study sample with all hospital patients in the study year in Germany the distribution of admissions by weekday, gender and age categories are given. The sample size was calculated to obtain a confidence interval of +/− 3% for a confidence level of 95%.

Two interviewers conducted the survey between January 2012 and March 2013. The 46 hospital departments with more than 200 ward teams in total were contacted and informed about the survey in the same pre-arranged manner. Interviewers received three training units to ensure uniform procedures in the patient survey.

The stratified sample was weighted for statistical analysis according to the distribution of all inpatients of the 11 disciplines in Germany (Table 1). Weighting was not adjusted for the level of care since the sample distribution is close to the distribution in all hospitals in Germany according to the level of care, with factors of 0.8 (standard care), 1.0 (specialist care) and 1.1 (maximum care). The software IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22 was used for statistical analysis to calculate the frequency distributions of criteria for hospital choice. Approximate 95% confidence intervals were calculated based on the standard normal distribution.

The questionnaire employed for the survey is the revised version of a questionnaire developed for an earlier project on the same issue [47]. The items offered in the item lists for decision criteria and sources of information follow those typically presented in the cited German and international studies [9, 22, 25,26,27,28, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The questionnaire was subjected to another pre-test using the “think aloud” method with ten hospitalised patients respectively from internal medicine, surgery, gynaecology and obstetrics in order to check the comprehensibility of items and revise where necessary. Patients may fill in the questionnaire either autonomously or assisted by an interviewer. For paediatric patients the questionnaire was adjusted to be completed by parents. The questionnaire addresses previous hospital experience, the context of admission and decision, sources of information (complete itemised list in Table 4) and decision criteria (complete itemised list in Table 5) and patients’ socio demography. The two questions on sources of information and predominant selection criteria explicitly enquire which sources and criteria the respondent actually used for the present hospital admission and which were essential in the decision. Participants were free to mark each single item that is applicable and relevant with a cross (multiple selection), but were not requested to answer each item. Additional remarks could be added on the questionnaire as free text. An English translation of the questionnaire is given as an additional file (Additional file 1).

Results

Sample

The study population comprised 2368 patients consecutively admitted to the 46 hospital departments of whom 1925 respondents constitute the study sample with completed questionnaires (22.0% completed alone, 78.0% together with interviewer) (Table 1). The reasons for the 18.7% non-respondents were: permanent (6.3%) or current (4.7%) physical or mental impairment, already discharged (4.0%) or termination of study (1.6%) prior to contact, questionnaire not returned (1.3%), refusal to participate (1.2%) or insufficient fluency in German (0.7%). A socio-demographic comparison revealed non-respondents as 48.6% male, which is 4% more than among respondents, and as a slightly larger proportion of the age categories over 75.

Table 2 lists participants’ information on socio-demography, previous hospital experience and admission day. Compared to all hospital patients in Germany receiving inpatient care in 2012, 2.3% more women were among respondents, less patients in the age category up to 24, and more in the age group from 50 to 79. Distribution of admissions by weekday mainly corresponded to the distribution of all hospital patients in the same year [Federal Statistical Office: statistical analysis on authors’ request, 2015]. With 47.2% the hospitalisation rate over the past twelve months was almost four times as high as among the general German population [52]. Almost two thirds have already known the hospital, and 42.7% the hospital department from a previous stay.

Hospital choice and time prior to admission

Responding to the question “Who decided on admission to this hospital?”, 63.0% said they decided themselves. Emergency rescue services decided in 12.4% of cases, followed by family doctors and outpatient care specialists (Table 3). Asked for the time between indication of hospitalisation and admission, 55.7% said they were admitted on the day of or one day after indication, 22.7% after 2 to 7 days, and 21.1% after more than 1 week (Table 3).

Sources of information

Previous personal experience of the hospital was the only source of information for 44.1% of patients; one quarter did not seek information; 30.5% used at least one external source of information (Table 4), whereby half of the latter group used several such sources (multiple response). Among the 14 defined external sources of information, relatives constituted the most frequent category with 14.2%. “Relatives” in this context refer to a patient’s personal social environment and include family, in-laws and partners, friends, acquaintances and colleagues. 11.6% consulted the specialist who provided outpatient treatment, 10.4% the family doctor, 9.1% the Internet and 4.7% a hospital outpatient department. Less than 2% respectively used the remaining 9 external sources of information.

Decision criteria

Among the group of 1207 patients who chose the hospital themselves, personal previous experience of the hospital was the most frequent main decision criterion (58.7%), and for 33.5% of respondents even the only one. 25.3% mention further criteria (Table 5). The reputation of a hospital and recommendations from their own outpatient caregivers were important criteria for approximately 30%, followed by distance from home (24.9%) and recommendations from relatives (20.9%). The next two criteria referred to a participative patient-doctor relationship, i.e. whether doctors take enough time for patients (13.6%), and whether patients were included in decisions on treatment (9.6%). All of the further 11 criteria which address more specific operationalised quality criteria were rated as important by between 6% and less than 1% respectively.

Discussion

In the German healthcare system almost two thirds of hospital patients perceive the decision on a hospital as their own choice, across disciplines, type of intervention and care level. This means that the declared health policy objective of patient participation in the choice of a hospital is often accomplished. This high percentage has to be contextualised by the high level of choice in the German health care system where patients have and expect free choice of providers in the ambulatory setting for primary and all secondary care by specialists, and now for years in the tertiary inpatient hospital care as well. Assigned care providers, often part of tax-funded health care systems with strong gate-keeping functions, are not characteristic for the German social health care system [53].

But what about the policy objective to have patients base their choice on public quality reporting made available for this purpose? Such performance reports are now published for each German hospital on an annual basis and available via Internet. However, more than half of patients are admitted to the hospital on the day of indication or one day later, so that in effect many patients do not have sufficient time to find, review, evaluate and compare hospital quality reports and make them part of their decision. It remains to determine how much time on average patients require – either alone or assisted by relatives – to obtain the required information on the planned intervention and base their hospital choice on a comparative decision. It appears evident that hours or even a few days are not enough for a majority of patients. Assuming at least one week prior to admission as sufficient, 21% of patients would have the time to review quality reports; if a period of at least 4 weeks is defined as sufficient time to obtain information, the percentage would be 6%. Apart from participation options and the time available prior to admission as significant framework conditions for hospital choice, another result of the study is of practical relevance as well. The majority of hospital patients have previous experience with hospitals; half of them were hospitalised during the past 12 months, and almost two thirds know the hospital personally from a previous stay, more than 40% from a stay even in the same department. This explains that for many patients (44%) their personal knowledge of the hospital constitutes the immediately available and exclusively used source of information. Only one third of patients obtain information from external sources, partially in addition to their own hospital experience. The most important external sources of information are relatives and outpatient caregivers, followed by the Internet and information received from the hospital. Hence this third of all patients, who indeed address external sources, rely especially on immediate and personal access to information based on familiar, trusted third parties.

As a result, personal previous experience with the hospital is the most frequent decision criterion for more than 50% of patients who choose the hospital themselves. This means that most patients choose and stay with what they know best in the situation being confronted with a hospitalisation. Recommendations from outpatient caregivers and the hospital’s reputation are relevant criteria for almost one third, followed by distance from home, relatives’ recommendations and aspects of an attentive and participative caregiver-patient relationship at the hospital. These criteria have far more relevance for patient decisions compared to single defined quality indicators often given in quality reports, such as complication rates, hygiene indices, intervention frequency or mortality figures. As with the favoured information sources, patients prefer aggregate and evaluative information in the form of personally conveyed experience or recommendation by familiar, trusted (expert) persons.

These results confirm the findings in international studies and indicate that patients behave similarly across very diverse organised and financed health care systems, and the patients’ choice behaviour seems to be rather stable over time even though more evidence-based quality information are available in the last years in many countries [9, 22, 27,28,29, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. But what is not addressed in our analyses are possible patient subgroup differences according to sociodemographic patient characteristics such as gender, age, socioeconomic status, migration status, or language competency. All these factors can influence choice behaviour and even the possibility to exercise choice as shown by Fotaki [54, 55].

What do our findings on hospital choice of a representative inpatient sample indicate? Is treatment quality as described best by scientifically sound, objective, evidence based quality measures not relevant to patients in choosing a hospital as their place of treatment? Yes and no, yes, the best quality is most relevant for patients, and no, for most patients quality indicators well presented in report cards are of low practical relevance. This fact is well known in the literature [7, 15, 20, 21, 23] and addressed as a cognitive problem of comprehension by the respective consumers. In fact, it might be that it is not a consumer who decides in the situation of a personal upcoming hospitalisation, but a patient. As Marshall and McLoughlin [33] point out the patients’ specific situation when choosing a hospital must be considered to understand their preference for aggregate information based on personal recommendation. These authors refer to psychological and sociological theories to understand and model patients’ decision-making: “These theories regard decision making as primarily a social process rather than a cognitive one. People draw on past experiences and are influenced by their expectations and fears and by the views of others - particularly people they trust”. [33]. Therefore free choice of a hospital is more than the possibility to choose, the time to consider, and the availability of well adapted quality information. The important role of trust building in this situation is described by Geuter [56] in a qualitative study with hospitalised patients: “Patients require individually and emotionally compatible information referring to professional care providers which they mainly obtain from their own social network or from outpatient caregivers, and which enable them to build up trust. Trust in the persons who provide care at the hospital constitutes a core factor determining a patient’s decision-making process”.

Limitations

The sample has some limitations. Medical disciplines not included in the study and covering 8% of admissions may affect results. But we see no evidence that these patients would behave in a basically different manner. The 19% non-respondents may distort our results to some degree; above all, the largest group (6%) of patients incapable of being interviewed on a permanent basis suggests a less active decision behaviour. The study was conducted in one German state exclusively, so that potential regional characteristics of other states remain unaccounted for. However, structures and procedures in hospital care do not differ fundamentally between German states. Possible effects have at least been partially offset by consideration of care levels and weighting adjustment according to medical disciplines on the federal level.

Conclusions

In view of the framework conditions identified and of patients’ considerations in choosing a hospital, two conclusions appear to be of particular relevance.

First, for lack of time, or as a matter of general preference, many patients require aggregate quality information in the form of recommendations instead of personally researched quality indicators when choosing a hospital. At least at the time of the indication for hospitalisation, outpatient caregivers are always involved in the patient’s decision-making, and frequently they are the only advisors with medical competence in the decision process. This fact assigns them the core role of “agents” who need to be responsible enough to base their advice on quality information and thus help the patient to use quality reporting. This applies also to the one third of cases where patients do not choose the hospital themselves. Access to, and forms of presenting, quality data should therefore be geared not only to the needs of patients but also specifically to the needs of these professional users [57, 58]. This agent function involves a high degree of responsibility, i.e. the motivation to keep the patient’s best interest in mind and not serve one’s own interests or those of third parties.

Second, personal experience with hospital treatment is a core criterion in a patient’s subsequent decision for or against a hospital, and is therefore of primary importance. Caregivers in the hospital may consistently take this fact into account. Their efforts to create a positive treatment experience should combine subject-specific medical competence with all aspects of an attentive and participative caregiver-patient relationship [59]. Hospital treatment of this kind receives positive feedback from patients, relatives, outpatient care providers, and also in terms of the hospital’s reputation. Depending on discipline and indication a number of activities may be helpful for some patient groups to develop trust in caregivers and hospitals, such as outpatient ward consultation, informative events or guided hospital tours.

References

Vrangbaek K, Robertson R, Winblad U, van de Bovenkamp H, Dixon a. Choice policies in northern European health systems. Health economics, Policy and Law. 2012;7(Special Issue 01):47–71.

Victoor A, Friele RD, Delnoij DMJ, Rademakers JJDJM. Free choice of healthcare providers in the Netherlands is both a goal in itself and a precondition: modelling the policy assumptions underlying the promotion of patient choice through documentary analysis and interviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:441.

Bernstein AB, Gauthier AK. Choices in health care: what are they and what are they worth? Med Care Res Rev. 1999;56(Suppl 1):5–23.

Kolstad JT, Chernew ME. Quality and consumer decision making in the market for health insurance and health care services. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(1 suppl):28S–52S.

Ringard Å. Equitable access to elective hospital services: the introduction of patient choice in a decentralised healthcare system. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2012;40(1):10–7.

Costa-i-Font J, Zigante V. ‘The Choice Agenda’ in European Health Systems: The Role of ‘Middle Class Demands’. The London School of Economics and Political Science ‚Europe in Question’ Discussion Paper Series. LEQS Paper No. 82/2014. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2522841 Accessed 10. Oct 2017.

Hibbard JH, Greene J, Sofaer S, Firminger K, Hirsh J. An experiment shows that a well-designed report on costs and quality can help consumers choose high-value health care. Health Aff. 2012;31(3):560–8.

Or Z, Cases C, Lisac M, Vrangbæk K, Winblad U, Bevan G. Are health problems systemic? Politics of access and choice under Beveridge and Bismarck systems. Health Economics, Policy and Law. 2010;5(3):269–93.

Lako CJ, Rosenau P. Demand-driven care and hospital choice. Dutch health policy toward demand-driven care: results from a survey into hospital choice. Health Care Anal. 2009;17(1):20–35.

Dixon A, Robertson R, Bal R. The experience of implementing choice at point of referral: a comparison of the Netherlands and England. Health Economics, Policy and Law. 2010;5(3):295–317.

Thomson S, Dixon A. Choices in health care: the European experience. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2006;11(3):167–71.

Foster MM, Earl PE, Haines TP, Mitchell GK. Unravelling the concept of consumer preference: implications for health policy and optimal planning in primary care. Health Policy. 2010;97(2–3):105–12.

Losina E, Plerhoples T, Fossel AH, et al. Offering patients the opportunity to choose their hospital for total knee replacement: impact on satisfaction with the surgery. Arthritis. Rheumatism. 2005;53(5):646–52.

E a.G J, Defuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, Staak CPF v d, C a.J d j. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(4):219–26.

Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks R, Overton V, Parrotta CD. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff. 2015;34(3):431–7.

Berwick DM. What “patient-centered” should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff. 2009;28(4):w555–65.

Fung CH, Lim Y-W, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):111–23.

Statistisches Bundesamt [Federal Statistical Office]. Destatis Fachserie 12 Reihe 6.1.1. Gesundheit, Grunddaten der Krankenhäuser 2012. [Health, basic data on hospitals 2012] Stand 20.3.2014. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2013. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Gesundheit/Krankenhaeuser/GrunddatenKrankenhaeuser.html;jsessionid=D8295A0266E4B90272BB2975AFDD8B1B.cae4 Accessed 10. Oct 2017.

Federal Joint Committee (G-BA): regulation on hospital admission. Bundesanzeiger 2003; Nr. 188: p. 22577. https://www.g-ba.de/informationen/richtlinien/16/. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Hibbard JH, Greene J, Daniel D. What is quality anyway? Performance reports that clearly communicate to consumers the meaning of quality of care. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(3):275–93.

Damman OC, Hendriks M, Rademakers J, Spreeuwenberg P, Delnoij DMJ, Groenewegen PP. Consumers’ interpretation and use of comparative information on the quality of health care: the effect of presentation approaches. Health Expect. 2012;15(2):197–211.

Dijs-Elsinga J, Otten W, Versluijs MM, et al. Choosing a hospital for surgery: the importance of information on quality of care. Med Decis Mak. 2010;30(5):544–55.

Vaiana ME, McGlynn EA. What cognitive science tells us about the Design of Reports for consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59(1):3–35.

Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. The public release of performance data - what do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence. JAMA. 2000;283(14):1866–74.

Zwijnenberg NC, Hendriks M, Damman OC, et al. Understanding and using comparative healthcare information; the effect of the amount of information and consumer characteristics and skills. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2012;12:101.

Federal Joint Committee (G-BA): regulations on hospital quality reports: https://www.g-ba.de/informationen/richtlinien/39/ Accessed 10. Oct 2017.

Turnpenny A, Beadle-Brown J. Use of quality information in decision-making about health and social care services--a systematic review. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2015;23(4):349–61.

Victoor A, Delnoij DMJ, Friele RD, Rademakers JJDJM. Determinants of patient choice of healthcare providers: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):272.

Ketelaar NABM, Faber MJ, Westert GP, Elwyn G, Braspenning JC. Exploring consumer values of comparative performance information for hospital choice. Qual Prim Care. 2014;22(2):81–9.

Ketelaar NABM, Faber MJ, Flottorp S, Rygh LH, Deane KHO, Eccles MP. Public release of performance data in changing the behaviour of healthcare consumers, professionals or organisations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD004538.

Faber M, Bosch M, Wollersheim H, Leatherman S, Grol R. Public reporting in health care: how do consumers use quality-of-care information? A systematic review. Med Care. 2009;47(1):1–8.

Geraedts M. Qualitätsberichte deutscher Krankenhäuser und Qualitätsvergleiche von Einrichtungen des Gesundheitswesens aus Versichertensicht. [Quality reports of German hospitals and quality comparisons of health care providers from the perspective of the insured] In: Böcken J, Braun B, Amhof R, Schnee M (eds): Gesundheitsmonitor 2006 [health monitor 2006]. Gesundheitsversorgung und Gestaltungsoptionen aus der Perspektive von Bevölkerung und Ärzten [health care and organization options from the perspective of the general public and physicians]. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung; 2006. p. 154–170.

Marshall M, McLoughlin V. How do patients use information on health providers? Br Med J. 2010;341(nov25 1):c5272.

Mansky T. Was erwarten potenzielle Patienten vom Krankenhaus? [What do prospective patients expect from a hospital?] In: Böcken J, Braun B, Repschläger U (eds): Gesundheitsmonitor 2012 [Health Monitor 2012]. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung 2012. p. 136-159.

Streuf R, Maciejek S, Kleinfeld A, Blumenstock G, Reiland M, Selbmann HK. Informationsbedarf und Informationsquellen bei der Wahl eines Krankenhauses. [information needs and information sources in search of a hospital.]. Gesundheitsökonomie und Qualitätsmanagement. 2007;12(02):113–20.

Vonberg R-P, Sander C, Gastmeier P. Consumer attitudes about health care acquired infections: a German survey on factors considered important in the choice of a hospital. Am J Med Qual. 2008;23(1):56–9.

Simon A. Patienteninvolvement und Informationspräferenzen zur Krankenhausqualität. [patient involvement and information preferences on hospital quality. Results of an empirical analysis]. Unfallchirurg. 2011;114(1):73–8.

Marang-van de Mheen PJ, Dijs-Elsinga J, Otten W, et al. The relative importance of quality of care information when choosing a hospital for surgical treatment: a hospital choice experiment. Med Decis Mak. 2011;31(6):816–27.

Zwijnenberg NC, Damman OC, Spreeuwenberg P, Hendriks M, Rademakers JJ. Different patient subgroup, different ranking? Which quality indicators do patients find important when choosing a hospital for hip- or knee arthroplasty? BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:299.

Geraedts M, de Cruppé W. Wahrnehmung und Nutzung von Qualitätsinformationen durch Patienten [how patients perceive and use quality information]. In: Klauber J, Geraedts M, Friedrich J, Wasem J, editors. Krankenhaus-report 2011 [hospital report 2011]. Schwerpunkt: Qualität durch Wettbewerb [topic: quality by competition]. Stuttgart: Schattauer; 2011. p. 93–104.

Victoor A, Delnoij D, Friele R, Rademakers J. Why patients may not exercise their choice when referred for hospital care. An exploratory study based on interviews with patients. Health Expectation. 2014; doi:10.1111/hex.12224.

Groenewoud S, Van Exel NJA, Bobinac A, Berg M, Huijsman R, Stolk EA. What influences patients’ decisions when choosing a health care provider? Measuring preferences of patients with knee arthrosis, chronic depression, or Alzheimer’s disease, using discrete choice experiments. Health Serv Res. 2015; doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12306.

Mühlbacher AC, Bethge S, Reed SD, Schulman KA. Patient preferences for features of health care delivery systems: a discrete choice experiment. Health Serv Res 2015; doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12345.

Tu HT, Lauer JR. Word of mouth and physician referrals still drive health care provider choice. Research Brief. 2008;9:1–8.

Feldman R, Jung K. Testing the Hirshleifer–Riley model: the values of information sources for a future hospital stay. J Consum Policy. 2012;35(3):355–71.

Abraham J, Sick B, Anderson J, Berg A, Dehmer C, Tufano A. Selecting a provider: what factors influence patients’ decision making? J Healthc Manag. 2011;56(2):99–114. discussion 114–5

de Cruppé W, Geraedts M. Wie wählen Patienten ein Krankenhaus für elektive operative Eingriffe? [how do patients choose a hospital for elective surgery?]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2011;54(8):951–7.

de Groot IB, Otten W, Dijs-Elsinga J, et al. Choosing between hospitals: the influence of the experiences of other patients. Med Decis Mak. 2012;32(6):764–78.

Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Birkmeyer JD. How do elderly patients decide where to go for major surgery? Telephone interview survey. Br Med J. 2005;331(7520):821.

Sofaer S, Crofton C, Goldstein E, Hoy E, Crabb J. What do consumers want to know about the quality of Care in Hospitals? Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6p2):2018–36.

Leister J, Stausberg J. Why do patients select a hospital? A conjoint analysis in two German hospitals. Journal of hospital marketing & public relations. 2007;17(2):13–31.

Rattay P, Butschalowsky H, Rommel A, et al. Utilization of outpatient and inpatient health services in Germany: results of the German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56(5–6):832–44.

Fotaki M, Boyd A, Smith L, et al. Patient Choice and the Organisation and Delivery of Health Services: Scoping Review. A Report to the NHS Service Delivery and Organisation (NCCSDO). London: SDO; 2006:174. http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_ES_08-1410-080_V01.pdf Accessed 10. Oct 2017.

Fotaki M. Is patient choice the future of health care systems? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2013;1(2):121–3. 10.15171/ijhpm.2013.22.

Fotaki M, Roland M, Boyd A, McDonald R, Scheaff R, Smith L. What benefits will choice bring to patients? Literature review and assessment of implications. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(3):178–84. doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2008.007163.

Geuter G, Weber J (2009) Informationsbedarf chronisch kranker Menschen bei der Krankenhauswahl – untersucht unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Internets [Information need of chronically ill persons when choosing a hospital – analysed in consideration of the internet]. Veröffentlichungsreihe des Instituts für Pflegewissenschaft an der Universität Bielefeld (IPW). P09–140. Bielefeld www.uni-bielefeld.de/gesundhw/ag6/downloads/ipw-140.pdf Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Geraedts M, Schwartze D, Molzahn T. Hospital quality reports in Germany: patient and physician opinion of the reported quality indicators. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:157.

Geraedts M, Hermeling P, de Cruppé W. Communicating quality of care information to physicians: a study of eight presentation formats. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(3):375–82.

Rademakers J, Delnoij D, de Boer D. Structure, process or outcome: which contributes most to patients’ overall assessment of healthcare quality? BMJ Quality & Safety. 2011;20(4):326–31.

Statistisches Bundesamt [Federal Statistical Office]. Fachserie 12 Reihe 6.4 Gesundheit. Fallpauschalenbezogene Krankenhausstatistik (DRG-Statistik) Diagnosen, Prozeduren, Fallpauschalen und Case Mix der vollstationären Patientinnen und Patienten in Krankenhäusern 2012. [Health. DRG-based hospital statistics diagnoses, procedures, DRG and case-mix of inpatients 2012] Stand 15.1.2014. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2013. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Gesundheit/Krankenhaeuser/FallpauschalenKrankenhaus.html Accessed 10. October 2017.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Prof. Dr. Frank Krummenauer, Witten/Herdecke University, for his statistical advice and Dipl.-Dolm. Christina Wagner, Witten/Herdecke University, for assistance in translating the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany, grant number 01GX1047. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, in collecting, analysing, and interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WDC: He made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, he drafted the manuscript. MG: He made substantial contributions to conception and design, interpretation of data, and has been involved in drafting the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee at Witten/Herdecke University approved the study, reference number: 95/2010.

Patient informed consent was obtained by a first contact of the patient by the medical ward staff asking if the patient would consider participating in this study. Then the patient was given detailed information and his/her questions were answered by the interviewer in a face-to-face contact. All patients received as well a hand-out with a written information on the study and a consent form for their own purpose and a second consent form which they signed and returned before the interview took place.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Patient questionnaire on hospital choice in Germany. English translation of the applied patient questionnaire to survey hospital choice in Germany. (PDF 246 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de Cruppé, W., Geraedts, M. Hospital choice in Germany from the patient’s perspective: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 17, 720 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2712-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2712-3