Abstract

Background

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are common chronic inflammatory respiratory diseases, which impose a substantial burden on healthcare systems and society. Fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting β2 agonists (LABA), often administered using dry powder inhalers (DPIs), are frequently prescribed to control persistent asthma and COPD. Use of DPIs has been associated with poor inhalation technique, which can lead to increased healthcare resource use and costs.

Methods

A model was developed to estimate the healthcare resource use and costs associated with asthma and COPD management in people using commonly prescribed DPIs (budesonide + formoterol Turbuhaler® or fluticasone + salmeterol Accuhaler®) over 1 year in Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom (UK). The model considered direct costs (inhaler acquisition costs and scheduled and unscheduled healthcare costs), indirect costs (productive days lost), and estimated the contribution of poor inhalation technique to the burden of illness.

Results

The direct cost burden of managing asthma and COPD for people using budesonide + formoterol Turbuhaler® or fluticasone + salmeterol Accuhaler® in 2015 was estimated at €813 million, €560 million, and €774 million for Spain, Sweden and the UK, respectively. Poor inhalation technique comprised 2.2–7.7 % of direct costs, totalling €105 million across the three countries. When lost productivity costs were included, total expenditure increased to €1.4 billion, €1.7 billion and €3.3 billion in Spain, Sweden and the UK, respectively, with €782 million attributable to poor inhalation technique across the three countries. Sensitivity analyses showed that the model results were most sensitive to changes in the proportion of patients prescribed ICS and LABA FDCs, and least sensitive to differences in the number of antimicrobials and oral corticosteroids prescribed.

Conclusions

The cost of managing asthma and COPD using commonly prescribed DPIs is considerable. A substantial, and avoidable, contributor to this burden is poor inhalation technique. Measures that can improve inhalation technique with current DPIs, such as easier-to-use inhalers or better patient training, could offer benefits to patients and healthcare providers through improving disease outcomes and lowering costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The burden of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Europe

Asthma and COPD are common chronic inflammatory respiratory diseases affecting 45 and 23 million people across Europe in 2011, respectively [1]. Respiratory diseases are the third leading cause of death in the European Union (EU) and have a considerable negative impact on patients’ physical and psychological wellbeing [2–5], imposing a substantial burden on healthcare providers and society as a whole [6].

Asthma and COPD comprise approximately 78 % of total direct healthcare costs associated with managing respiratory diseases in the EU, amounting to €42.8 billion in 2011 [7]. The economic burden of asthma and COPD increases markedly when indirect costs – such as those associated with lost productivity and carer time – are considered. In Europe, the annual indirect costs of asthma and COPD are approximately equal to the direct healthcare costs, totalling €14.4 billion and €25.1 billion in 2011, respectively [7].

Treatment of asthma and COPD

There are a broad range of options available for the management of asthma and COPD. Controller medicines, such as inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), long-acting β2 agonists (LABA) and anti-immunoglobulin E (anti-IgE), are taken preventatively to manage asthma and COPD – although the effectiveness of anti-IgE has been questioned [8]. In contrast, short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMA) and short-acting β2 agonists (SABA) are used as rescue medications to provide immediate relief from exacerbations [9, 10]. For patients with persistent asthma and COPD, global clinical guidelines recommend treatment with a fixed-dose combination (FDC) of ICS + LABA, either as a controller medication with as-needed SABA as rescue medication, or as both controller and rescue medication [9, 10].

Asthma and COPD medicines are commonly administered using either a pressurised metered dose inhaler (pMDI) or a dry powder inhaler (DPI) [9]. pMDIs function by user activation of a pressurised propellant [11], requiring a degree of dexterity, skill and training to co-ordinate actuation and inhalation in order to deliver the correct dose [9, 12]. DPIs are breath-actuated [11], with little hand-breath co-ordination required, making them easier to use than pMDIs [9, 13, 14], and are typically recommended over pMDIs [15, 16]. Clinicians and guidelines from international bodies recognise that the choice of medicine and inhaler is critical for achieving successful management of asthma and COPD [15–17].

Poor inhalation technique

Critical inhaler errors – defined as errors which significantly reduce, or prevent entirely, deposition of medicine in the lungs [18] – can be considered a measure of poor inhalation technique. In 2011, Melani and colleagues published results of a three-month, cross-sectional study of 1,664 Italian asthma and COPD patients using DPIs, which found that 44 % of people using budesonide + formoterol (BF) Turbuhaler® (Symbicort® Turbuhaler®) and 34 % of people using fluticasone + salmeterol (FS) Accuhaler® (Seretide® Accuhaler®) had poor inhalation technique [19]. Moreover, a systematic review of patients with asthma and COPD found that up to 94 % of DPI users made at least one inhaler error when examined by a healthcare professional (HCP) [20].

Importantly, HCPs may also demonstrate poor inhalation technique. Independent studies from multiple countries have shown that at least a third of – and in some cases all – HCPs performed at least one critical error with pMDIs and DPIs [21–25]. Similarly, a review of 20 studies of pMDI and DPI use found that more than three quarters of nurses, and over a third of respiratory specialists, did not perform all stages of inhalation correctly [26]. The frequency with which HCPs can demonstrate poor inhalation technique indicates that commonly prescribed inhalers are difficult to use. As HCPs are charged with teaching patients to use inhalers effectively, poor inhalation technique among HCPs may result in patients receiving incorrect or inconsistent advice and training.

Studies from many countries have shown that poor inhalation technique correlates with reduced disease control and increased use of healthcare resources [16, 27], which in turn negatively impacts patient health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [28]. Therefore, poor inhalation technique presents a potentially considerable, and avoidable, burden to healthcare organisations and patients alike. Although it is widely accepted that inhalation technique is a significant factor in the control of respiratory disease [29], its contribution to the cost of asthma and COPD management has not been quantified. An economic model was designed to assess the healthcare and societal burden of managing asthma and COPD using DPIs containing ICS + LABA FDCs, and how this may be impacted by poor inhalation technique.

Methods

Model design

A burden-of-illness model was developed from a societal perspective for Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom (UK). These countries were chosen in order to give a range of population sizes, geographical locations and economies. The model assessed the economic burden of managing asthma and COPD using either BF Turbuhaler® or FS Accuhaler® over 1 year, and estimated the contribution of poor inhalation technique to this burden. These inhalers were chosen as they are the most commonly prescribed DPIs in Europe [30].

Direct and indirect costs were included in the model. Direct costs included inhaler acquisition costs, scheduled healthcare costs (visits to nurses, general practitioners (GPs), and specialists) and unscheduled healthcare costs (hospitalisations, emergency department (ED) visits, and additional courses of antimicrobials or oral corticosteroids (OCS)). Indirect costs were determined using the number of productive days lost due to asthma or COPD. Costs for Sweden and the UK were converted to Euro using historical exchange rates [31]. All costs were inflated to 2015 values based on healthcare-specific consumer price indices (CPIs) [32–34], except the cost of each lost productive day, which was inflated using national CPIs [35].

Parameters

Model population

Adult asthma or COPD patients using BF Turbuhaler® or FS Accuhaler® were included in the analysis. This population was estimated based on the number of individuals aged 18 years and older with diagnosed asthma or COPD, according to population estimates from national statistical databases [36–38] and epidemiological data from national regulatory bodies [39–42]. The proportion of patients receiving FDCs of ICS + LABA to manage their asthma or COPD was calculated based on data from national regulatory bodies and published studies [39–41, 43, 44]. The annual number of patients receiving BF Turbuhaler® or FS Accuhaler®, at each delivered dose strength, was estimated using 2014 national sales data (moving annual total; a rolling measure of data from the past year taken every month) [30] (Table 1).

Inhaler acquisition costs

Costs of BF Turbuhaler® and FS Accuhaler® in Spain, Sweden and the UK were sourced from the Ministry of Health [45], national sales data (moving annual total) [30] and the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS) [46, 47], respectively (Table 2).

Resource use and healthcare costs

Direct and indirect healthcare events and costs are displayed in Table 3. The majority of resource use inputs and all costs were derived from country-specific sources, such as national or regional registries and peer-reviewed articles; where necessary, reasonable assumptions were made to utilise applicable data.

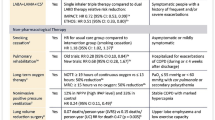

Impact of poor inhalation technique

The proportion of patients demonstrating poor inhalation technique with BF Turbuhaler® (43.5 %) and FS Accuhaler® (34.5 %) was based on the study by Melani and colleagues [19]. It was assumed that the increased risk of unscheduled healthcare events over baseline due to poor inhalation technique reported in this Italian study [19] was applicable to other European countries (Table 4). We conservatively assumed that the increased risk of lost productivity due to poor inhalation technique was equal to the lowest risk increase reported for any other event (ie hospitalisation).

Sensitivity analyses

One-way sensitivity analyses were performed using upper and lower bounds based on reported values where possible – if no data were available bounds were set at ±20 %. The following parameters were varied:

-

Proportion of patients using ICS + LABA FDCs (±10 %) – variation accounts for changes in prescription habits

-

Number of doses per day – the upper (3) and lower (1) bounds reflect recommendations in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPCs) for each inhaler

-

Cost of hospitalisation (±20 %)

-

Cost of ED visits (±20 %)

-

Cost of additional courses of antimicrobials (±20 %)

-

Cost of additional courses of OCS (±20 %)

-

Proportion of patients with poor inhalation technique (±20 %)

Results

Number of events

The annual number of events is shown in Table 5. The largest eligible patient population was in the UK, followed by Spain and Sweden. The number of productive days lost due to asthma and COPD aligned with the relative size of the eligible population for each country, and comprised 83.8–93.8 % of the total number of all reported events in each country.

Costs

The estimated total direct costs of asthma and COPD in 2015 were predicted to be €813 million, €560 million and €774 million in Spain, Sweden and the UK, respectively. Despite having the largest eligible population, the costs of asthma and COPD per patient were lowest in the UK, while the highest per-patient costs were incurred in Spain (Fig. 1). Inclusion of indirect costs increased the burden of asthma and COPD substantially, with the costs per-patient rising to €2,474, €3,675 and €4,060 in Spain, Sweden and UK, respectively, resulting in total annual costs of €1.4 billion, €1.7 billion and €3.3 billion, respectively. Despite patients in Spain losing more productive days on average compared with patients in Sweden, total annual indirect costs in Spain were approximately half of those for Sweden (€0.60 billion compared with €1.18 billion, respectively).

Poor inhalation technique

The contribution of poor inhalation technique to the burden of asthma and COPD is summarised in Table 6. Across the three countries studied, 15.4–20.7 % of unscheduled healthcare events and costs were attributable to poor inhalation technique.

Figure 2 reveals that the per-patient costs of unscheduled healthcare events due to poor inhalation technique were highest in Spain (€109), followed by Sweden (€55) and the UK (€21). Per-patient costs in Spain were substantially higher than in the other two countries due to the high costs of hospitalisation. The contribution of additional courses of antimicrobials and OCS to the cost burden of poor inhalation technique in Spain and Sweden was negligible; however, in the UK, these costs were each greater than the costs of ED visits.

The total cost burden of poor inhalation technique more than doubled when productivity losses were taken into account (Table 6). These indirect costs were highest in the UK (€390 million), followed by Sweden (€194 million) and Spain (€93 million). Inclusion of indirect costs increased the total per-patient costs of poor inhalation technique to €271 in Spain, €466 in Sweden and €506 in the UK.

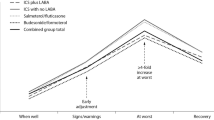

Sensitivity analyses

The results of the one-way sensitivity analyses are shown in Fig. 3. The model was most sensitive to the proportion of patients using ICS + LABA, and moderately sensitive to the number of doses per day and the cost per hospitalisation. The ranking of each parameter was similar across the three countries; with regards to Spain, the model was more sensitive to the costs of hospitalisation than to the number of doses per day for mid-strength inhalers, while the model in Sweden was more sensitive to the number of doses per day for mid strength inhalers than high strength inhalers.

One-way sensitivity analyses. *Patients prescribed 320/9 μg or 500 μg inhalers, **Patients prescribed 160/4.5 μg or 250 μg inhalers, ***Patients prescribed 80/4.5 μg or 100 μg inhalers. Sensitivity analyses for a) Spain, b) Sweden and c) the UK. Parameters were varied as described in the Methods section. Results are displayed from the greatest change to the least change for each country. Values are subject to rounding

Discussion

We developed a model to estimate the burden of managing asthma and COPD with the most commonly prescribed DPIs in Spain, Sweden and the UK. Our analysis estimated the burden to be substantial, with 572,317, 473,022 and 803,821 adults using BF Turbuhaler® or FS Accuhaler® in Spain, Sweden and the UK, respectively. Given the population size differences between countries, the proportion of adults included in the model for Sweden was high relative to those values estimated for Spain and the UK – this was likely due to a higher prevalence of asthma and COPD, and higher prescription rates of BF Turbuhaler®.

A total of 5.5 million scheduled and 2.8 million unscheduled healthcare events were estimated to occur across the three countries annually. The highest number of scheduled healthcare events was estimated to occur in Spain, primarily driven by a higher incidence of specialist visits compared with other countries. The highest number of unscheduled healthcare events occurred in Sweden, despite it having the lowest eligible patient population among the countries studied; this may be due to the high prescription rates of BF Turbuhaler®, as patients using this inhaler have a higher risk of incurring unscheduled healthcare events than patients using FS Accuhaler® [19].

The model estimated direct per-patient costs (inhaler acquisition costs, scheduled healthcare costs and unscheduled healthcare costs) of disease management in Spain, Sweden and the UK to be €1,421, €1,183 and €963, respectively. These values are in broad agreement with previously published cost estimates. For example, in 2007, a prospective observational study of 627 asthma patients in Spain reported a direct annual cost of €1,533 per patient [48], while in 2003 a separate, multicentre, epidemiological study of 10,711 Spanish COPD patients determined the cost per patient to be €1,922 [49]. When inflation is applied to these values, the reported annual per-patient costs of asthma and COPD in Spain are €1,675 and €2,111, respectively [32]. Minor differences in cost estimates compared with our results are likely due to variations in methods of data collection and analysis, treatment regimens, patient populations and disease severity, and regional healthcare costs.

In the UK, the direct cost burden of asthma and COPD was reported to be £1.8 billion in 2012 [50], which, when converted to Euro and inflated to 2015 values [31], equates to €2.6 billion. Our analysis estimated the direct cost of managing patients using BF Turbuhaler® or FS Accuhaler® – who represent 20 % of the total UK asthma and COPD patient population – to be €774 million, which is approximately 29.8 % of the reported total costs for the UK. Therefore, assuming the two studies are comparable, patients considered by our model have higher than average costs of asthma and COPD management, which is to be expected as these patients have persistent forms of disease.

The model showed that the indirect costs of asthma and COPD exceeded the direct costs in Sweden and the UK, while the two were approximately equal in Spain. This is similar to results reported by the European Respiratory Society (ERS), which stated that direct and indirect costs for the whole of Europe were approximately equal [7]. Estimating the indirect costs associated with a disease is challenging, as they are not well defined and can be calculated in multiple ways. Whilst disability and family carer costs add to the indirect burden of disease [7], these costs were not included in our analysis. Instead, productivity losses were calculated based solely on the number of work days lost and the average salary within each country. Our estimation of the indirect burden of asthma and COPD is therefore conservative, and the true costs would likely eclipse those reported here.

Studies from many countries have shown that poor inhalation technique – which is commonly observed in users of BF Turbuhaler® and FS Accuhaler® [19] – correlates with reduced disease control and increased healthcare costs [16, 27]. However, to our knowledge, no in-depth attempt has previously been made to quantify the contribution of poor inhalation technique to overall healthcare costs in DPI users. Our analysis estimated the total direct costs of poor inhalation technique to be €105 million annually across the three countries, amounting to 4.9 % of the total direct costs of asthma and COPD management. When lost productivity was included, the total costs of poor inhalation technique rose to €782 million (12.2 %) in Spain, Sweden and the UK. Poor inhalation technique therefore represents a substantial budgetary and societal burden.

Several studies have shown that patient inhalation technique can be improved with additional training [27, 51, 52], however, regular check-ups are required to maintain correct inhalation technique over time [51]. Additionally, HCPs charged with teaching patients to use inhalers correctly often demonstrate poor inhalation technique themselves [26]. Education of HCPs and patients is an important step in improving the management of asthma and COPD [53]; however, training alone is unlikely to be sufficient for achieving optimal control [54]. Consequently, the introduction of novel, easy-to-use inhalers that have the potential to improve patient inhalation technique will play an important role in optimising control of respiratory diseases [54]. Inhalers that are more intuitive to use or require less dexterity than BF Turbuhaler® or FS Accuhaler® could reduce the likelihood of patients making critical inhaler errors [54], which would lower the risk of unscheduled healthcare events [19], and – provided acquisition costs of these novel inhalers are comparable to currently prescribed DPIs – therefore result in direct cost savings. Indeed, correct choice of inhaler is seen as a critical factor in the management of asthma and COPD [15–17], as increased patient satisfaction with an inhaler is associated with improved adherence to treatment and enhanced disease control [55]. Introduction of novel inhalers that address current unmet needs could therefore reduce the patient and economic burden associated with asthma and COPD management.

Sensitivity analyses showed that the model was most sensitive to the proportion of patients using ICS + LABA, and moderately sensitive to the number of doses per day and the costs per hospitalisation; variations among the remaining inputs had little effect on the output of the model. We therefore conclude that the model is robust. However, there are a number of limitations to the model. Firstly, the model does not consider the frequency with which patients take their medication, the impact of patient adherence or comorbidities. Whilst poor patient adherence is associated with increased use of healthcare resources [56], the absence of data supporting the contribution of adherence to the different costs considered in this analysis meant that we did not factor adherence into the model calculations. Comorbidities contribute to the number of exacerbations [57] and, subsequently, days of lost productivity [58] experienced by patients; however, the costs of comorbidities are hard to quantify, and were therefore not included in this analysis. This, together with the exclusion of patient adherence, likely results in conservative estimates of asthma and COPD management costs.

Secondly, visits to nurses, GPs and specialists were based on the total number of visits per year. The model considered all of these visits to be scheduled healthcare events, though in actuality some of these visits would be due to exacerbations and would therefore be classed as unscheduled healthcare events. As such, the model may overestimate the cost of scheduled healthcare events and underestimate the cost of unscheduled healthcare events and, consequently, our reported burden of poor inhalation technique is likely to be conservative. Therefore, any reduction in the number of unscheduled healthcare events will likely lead to greater cost savings than would be predicted by our model.

Thirdly, the prevalence of poor inhalation technique in the countries studied was assumed to be the same as reported in Italy [19], and the increased risk of healthcare resource use due to poor inhalation technique was assumed to be the same across all countries. While practices perceivably vary from country to country, no studies have estimated the impact of poor inhalation technique in Spain, Sweden or the UK. This information would help provide a more accurate estimate of the costs of poor inhalation technique within these countries.

Finally, this study focusses on the impact of poor inhalation technique on unscheduled healthcare use and productivity losses only. Reduced disease control due to poor inhalation technique likely reduces patient HRQoL, which is not measured in this analysis. Melani and colleagues reported a significant association between asthma and COPD patients making at least one critical inhaler error and several patient-reported outcomes, such as limitations during everyday life, shortness of breath, use of rescue inhaler, and sleep disturbance [19]. Applying quantifiable estimates to such outcomes would emphasise further the burden of poor inhalation technique.

Conclusions

The cost of managing asthma and COPD with DPIs is considerable. A substantial, and avoidable, contributor to this burden is poor inhalation technique with currently prescribed DPIs. Measures that can improve inhalation technique with current DPIs, such as easier-to-use inhalers and better patient training, could offer benefits to patients and healthcare providers through improved disease outcomes and lowered costs.

Abbreviations

BF, budesonide + formoterol; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPI, consumer price index; DPI, dry powder inhaler; ED, Emergency department; ERS, European Respiratory Society; EU, European Union; FDC, fixed dose combination; FS, fluticasone + salmeterol; GP, general practitioner; HCP, healthcare professional; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; ISPOR, International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes research; LABA, long-acting β2 agonists; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonists; MIMS, monthly Index of Medical Specialities; OCS, oral corticosteroids; pMDI, pressurised metered dose inhaler; SABA, short-acting β2 agonists; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonists; SmPC, summary of product characteristics; UK, United Kingdom

References

World Health Organization. World Health Survey. Available from: www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/en/. Accessed: Jan 2012.

European Respiratory Society (ERS). Assessing asthma quality of life: its role in clinical practice. Available from: http://www.ers-education.org/lrMedia/2005/pdf/40500.pdf. Accessed: Nov 2013

Gonzalez-Barcala FJ et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in adults with asthma. A cross-sectional study. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2012;7(1):32.

Apfelbacher CJ et al. Validity of two common asthma-specific quality of life questionnaires: juniper mini asthma quality of life questionnaire and Sydney asthma quality of life questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:97.

Stahl E et al. Health-related quality of life is related to COPD disease severity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:56.

European Commission. Cause of death statistics. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Causes_of_death_statistics. Accessed: Nov 2013

European Respiratory Society. European lung white book. 2013. Available from: http://www.erswhitebook.org/chapters/. Accessed: Oct 2013

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Omalizumab for treating severe persistent allergic asthma. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta278/chapter/4-Evidence-and-interpretation#summary-of-appraisal-committees-key-conclusions. Accessed: Mar 2016.

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). 2015. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/. Accessed: Mar 2015.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). 2015. Global strategy for diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. Available from: http://goldcopd.org/. Accessed: Mar 2015.

Newman SP. Inhaler treatment options in COPD. Eur Resp Rev. 2005;14(96):102–8.

Chrystyn H. The Diskus: a review of its position among dry powder inhaler devices. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(6):1022–36.

Molimard M et al. Assessment of handling of inhaler devices in real life: an observational study in 3811 patients in primary care. J Aerosol Med. 2003;16(3):249–54.

Roche N et al. Effectiveness of inhaler devices in adult asthma and COPD. EMJ Respir. 2013;1:64–71.

Laube BL et al. What the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapies. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(6):1308–31.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. QS25 Quality standard for asthma. Available from: http://publications.nice.org.uk/quality-standard-for-asthma-qs25. Accessed: Dec 2013.

Dekhuijzen PNR et al. Prescription of inhalers in asthma and COPD: towards a rational, rapid and effective approach. Respir Med. 2013;107(12):1817–21.

Broeders ME et al. The ADMIT series-issues in inhalation therapy. 2. Improving technique and clinical effectiveness. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18(2):76–82.

Melani AS et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):930–8.

Lavorini F et al. Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2008;102(4):593–604.

P710. Evaluation of inhaler devices device usage skills among the medical personnels (pulmonologist, family physician, nurse), pharmacist and assistant pharmacist. Available from: http://lrp.ersnet.org//abstract_print_13/files/83.pdf. Accessed: Dec 2013

Osman A et al. Are Sudanese community pharmacists capable to prescribe and demonstrate asthma inhaler devices to patrons? A mystery patient study. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2012;10(2):110–5.

Kim SH et al. Inappropriate techniques used by internal medicine residents with three kinds of inhalers (a metered dose inhaler, Diskus, and Turbuhaler): changes after a single teaching session. J Asthma. 2009;46(9):944–50.

Basheti IA et al. User error with Diskus and Turbuhaler by asthma patients and pharmacists in Jordan and Australia. Respir Care. 2011;56(12):1916–23.

Lenney J et al. Inappropriate inhaler use: assessment of use and patient preference of seven inhalation devices. Respir Med. 2000;94(5):496–500.

Self TH et al. Inadequate skill of healthcare professionals in using asthma inhalation devices. J Asthma. 2007;44(8):593–8.

Crane MA et al. Inhaler device technique can be improved in older adults through tailored education: findings from a randomised controlled trial. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14034.

Newman S. Improving inhaler technique, adherence to therapy and the precision of dosing: major challenges for pulmonary drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11(3):365–78.

Price D et al. Inhaler competence in asthma: common errors, barriers to use and recommended solutions. Respir Med. 2013;107(1):37–46.

IMS Midas, MAT 06/’14. Data on file. TEVA Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Dec 2014

XE.com. Current and historical rate tables. Available from: http://www.xe.com/currencytables/. Accessed May 2015.

Office for National Statistics (ONS). Consumer Price Indices (CPI) tables. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/taxonomy/index.html?nscl=Consumer+Prices+Index#tab-data-tables. Accessed: Jun 2015.

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (INE). Consumer Price Indices (CPI) Report. Available from: http://www.ine.es/buscar/searchResults.do;jsessionid=BABCE790BC0E88D54B2F3A160D023613.buscar03?searchString=inflacion&Menu_botonBuscador=Search&searchType=DEF_SEARCH&startat=0&L=0. Accessed: Jun 2015.

Statistiska centralbyrån. Consumer Price Index (CPI). Available from: http://www.scb.se/en_/Finding-statistics/Statistics-by-subject-area/Prices-and-Consumption/Consumer-Price-Index/Consumer-Price-Index-CPI/Aktuell-Pong/33779/Consumer-Price-Index-CPI/291619/. Accessed: Jun 2015.

Historical inflation – CPI inflation year pages. Available from: http://inflation.eu/inflation-rates/historic-cpi-inflation.aspx. Accessed: May 2015.

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (INE). Short-term population projections 2013–23. Available from: http://www.ine.es/jaxi/menu.do?type=pcaxis&path=/t20/p269/&file=inebase. Accessed: Jun 2015.

Statistiska centralbyrån. Statistikdatabasen. 2014. Available from: http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Statistikdatabasen/Accessed: Jun 2015.

Office for National Statistics. Population estimates for UK England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, mid-2014. Jun 2015. Available at: http://ons.gov.uk/ons/taxonomy/index.html?nscl=Population#tab-data-tables. Accessed: Sept 2014.

Plaza V et al. GEMA (guía española de manejo del asma). Arch Bronconeumol. 2009;45(7):2–35.

Ancochea J. Infradiagnóstico de la enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica en mujeres cuantificación del problema, determinantes y propuestas de acción. Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49(6):223–9.

LIF – de forskande läkemedelsföretagen. Fokus på nationella riktlinjer och uppnådda behandlingsresultat för astma- och KOL-vården. Available from: http://www.lif.se/statistik/. Accessed: Apr 2014.

UK Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) database. 2013. Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB18887. Accessed: May 2014.

Gars T et al. Luftsvägsregistret Årsrapport 2012 års resultat. Available from: http://mb.cision.com/Public/13/9471839/b8b442f2b6025c5b.pdf. Accessed: Apr 2014.

Covvey J et al. Is the BTS/SIGN guideline confusing? A retrospective database analysis of asthma therapy. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(3):209–5.

Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Información sobre los productos incluidos en la prestación farmacéutica del SNS. Available from: http://www.msssi.gob.es/profesionales/nomenclator.do?metodo=buscarProductos. Accessed: May 2015.

Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS). Symbicort® Turbuhaler®. Available from: http://www.mims.co.uk/. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS). Seretide® Accuhaler®. Available from: http://www.mims.co.uk/. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Martinez-Moragon E et al. Economic cost of treating the patient with asthma in Spain: the AsmaCost study. Arch Bronconeumol. 2009;45(10):481–6.

de Miguel DJ et al. Determinants and predictors of the cost of COPD in primary care: a Spanish perspective. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3(4):701–12.

An outcomes strategy for COPD and asthma: NHS companion document. 2012. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216531/dh_134001.pdf. Accessed: May 2014.

Basheti IA et al. Improved asthma outcomes with a simple inhaler technique intervention by community pharmacists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(6):1537–8.

Toumas-Shehata M et al. Exploring the role of quantitative feedback in inhaler technique education: a cluster-randomised, two-arm, parallel-group, repeated-measures study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14071.

Basheti IA et al. Inhaler technique training and health-care professionals: effective long-term solution for a current problem. Respir Care. 2014;59(11):1716–25.

Virchow JC et al. A review of the value of innovation in inhalers for COPD and asthma. JMAHP. 2015;3:28760.

Small M et al. Importance of inhaler-device satisfaction in asthma treatment: real-world observations of physician-observed compliance and clinical/patient-reported outcomes. Adv Ther. 2011;28:202–12.

Bender B, Rand C. Medication non-adherence and asthma treatment cost. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:191–5.

Panek M et al. The epidemiology of asthma and its comorbidities in Poland – health problems of patients with severe asthma as evidenced in the Province of Lodz. Respir Med. 2016;112:31–8.

Bahadori K et al. Economic burden of asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:24.

Socialstyrelsen. Socialstyrelsens riktlinjer för vård av astma och kroniskt obstruktiv lungsjukdom (KOL). 2004. Available from: www.allergicentrumstockholm.se/getfile.ashx?cid=284965&cc=3&refid=3. Accessed: May 2015.

Masa J et al. Costes de la EPOC en España. Estimación a partir de un estudio epidemiológico poblacional. Arch Bronconeumol. 2004;40(2):72–9.

Orden 731/2013, de 6 de septiembre, del Consejero de Sanidad, por la que se fijan los precios públicos por la prestación de los servicios y actividades de naturaleza sanitaria de la Red de Centros de la Comunidad de Madrid.

Jansson S et al. The economic consequences of asthma among adults in Sweden. Respir Med. 2007;101(11):2263–70.

Södra regionvårdsnämnden. Regionala priser och ersättningar för södra sjukvårdsregionen. 2014. Available from: http://www.skane.se/Upload/Webbplatser/Sodra%20regionvardsnamnden/prislista/2014/helaprislistan2014.pdf. Accessed: Apr 2014.

National Records of Scotland. Scotland’s Census. 2011. Available from: http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/ods-web/area.html#. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Information Services Division Scotland. Practice Team Information programme. 2003/04–2012/13. Available from: http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/General-Practice/GP-Consultations/. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Quality and Outcomes Framework. National prevalence summaries by register and year. 2004/05–2012/13. Available from: http://www.isdscotland.org/qof. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Personal Social Services Research Unit. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. 2013. Available from: http://www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/2013/. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Martínez-Moragón E et al. Coste economico del paciente asmatico en España (Estudio AsmaCost). Arch Bronconeumol. 2009;45(10):481–6.

Erickson S et al. The impact of allergy and pulmonary specialist care on emergency asthma utilization in a large managed care organization. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5):1443–65.

Jansson SA et al. Health economic costs of COPD in Sweden by disease severity – has it changed during a ten years period? Respir Med. 2013;107(12):1931–8.

COPD Uncovered. Healthcare utilization in COPD: the burden carried by primary care. 5th ed. Toronto: IPCRG World Conference; 2010.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Hospital Episode Statistics for England. Inpatient statistics. 2011–12. Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hes. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Quality and Outcomes Framework achievement, prevalence and exceptions data, 2012/13. Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB12262. Accessed: May 2014.

Department of Health. Payments by results in the NHS: tariff for 2013 to 2014. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/payment-by-results-pbr-operational-guidance-and-tariffs. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Accordini S et al. The cost of persistent asthma in Europe: an international population-based study in adults. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;160:93–101.

Forum. Clinical Review. Gauging the need for nurse-led clinics. May 2010.

Guia española de la EPOC (GesEPOC). Available from: http://www.msssi.gob.es/profesionales/nomenclator.do?metodo=verDetalle&prod=691253. Accessed: May 2014.

Tandvårds och läkemedelsförmånsverket (TLV). Beslut - Sök i databasen – Läkemedel. Available from: http://www.tlv.se/beslut/sok/lakemedel/. Accessed: May 2014

British National Formulary. Ketek. Available from: https://www.bnf.org/. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Johnston S et al. The effect of telithromycin in acute exacerbations of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):589–600.

Cole S et al. ‘The blue one takes a battering’ why do young adults with asthma overuse bronchodilator inhalers? A qualitative study. BMJ. 2013;3(2):e002247.

British National Formulary. Prednisolone. Available from: http://www.bnf.org/bnf/index.htm. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Boggon R et al. Variability of antibiotic prescribing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:32.

Albert R et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):689–98.

British National Formulary. Azithromycin. Available from: http://www.bnf.org/bnf/index.htm. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Ojeda P et al. Coste Asma Study. Costs associated with workdays lost and utilization of health care resources because of asthma in daily clinical practice in Spain. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2013;23(4):234–41.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). StatExtracts. Average annual hours actually worked per worker. 2013. Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ANHRS. Accessed: May 2015.

Statistiska centralbyrån. Statistikdatabasen. 2013. Available from: http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Statistikdatabasen/. Accessed: Apr 2014.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). StatExtracts. Average annual hours actually worked per worker. 2012. Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ANHRS. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Demoly P et al. Repeated cross-sectional survey of patient-reported asthma control in Europe in the past 5 years. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21(123):66–74.

Confederation of British Industry: The Voice of Business. Healthy Returns. Absence and workplace health survey. 2011. Available from: http://www.cbi.org.uk/media-centre/news-articles/2011/05/healthy-returns-absence-and-workplace-health-survey-2011/. Accessed: Feb 2014.

Halpin DM, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the disease and its burden to society. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3(7):619–23.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Guilherme Safioti and Fredrik Lindqvist from Sweden, Laura Garcia-Bujalance and Rainel Sanchez from Spain, and John Holmes, James Dale and Simon Chandler from the UK (all employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals) for their support with providing local data. We would also like to thank Lewis Ruff (Covance Market Access, London) for discussions and guidance relating to the model.

Funding

Covance Market Access, London, received funding from Teva Pharmaceuticals Europe B.V. to conduct this study and develop the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The inputs used for the main analysis and sensitivity analyses can be found in the accompanying Additional file 1.

Authors’ contributions

Alexandra Lewis, Michael Blackney, Saku Torvinen and Adam Plich contributed to the development of the model, data collection and validation. Alex Watson performed the country-wise data analysis and, along with Alexandra Lewis and Michael Blackney, drafted the manuscript. Richard Dekhuijzen, Henry Chrystyn, Saku Torvinen and Adam Plich provided critical review of the manuscript and guidance. All authors contributed to the writing of the final manuscript, and have approved it for publication.

Authors’ information

A.L., A.T.W. and M.B. are employees of Covance Market Access, London.

S.T. and A.P. are employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals Europe B.V.

P.N.R.D. is Professor of Pulmonology at the Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

H.C. is Emeritus Professor of Pharmacy at the University of Huddersfield and a fellow of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain.

Competing interests

In the last 3 years, Richard Dekhuijzen and/or his department have received research grants, unrestricted educational grants, and/or fees for lectures and advisory board meetings from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, MundiPharma, Novartis, Takeda and Teva Pharmaceuticals Europe B.V.

Henry Chrystyn has no shares in any pharmaceutical companies. He has received sponsorship to carry out studies, together with some consultant agreements and honoraria for presentations from several pharmaceutical companies that market inhaled products (Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Innovata Biomed, Meda, MundiPharma, Napp Pharmaceuticals, NorPharma, Orion, Sanofi, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Truddell Medical International, UCB, Zentiva). He has also received research sponsorship from grant-awarding bodies (Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and Medical Research Council (MRC)).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Inputs used in the model for the analyses presented in this publication. (XLSX 20 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lewis, A., Torvinen, S., Dekhuijzen, P.N.R. et al. The economic burden of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the impact of poor inhalation technique with commonly prescribed dry powder inhalers in three European countries. BMC Health Serv Res 16, 251 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1482-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1482-7