Abstract

Background

During interviews, medical students may feel uncomfortable asking questions that might be important to them, such as parental leave. Parental leave policies may be difficult for applicants to access without asking the program director or other interviewers. The goal of this study is to evaluate whether parental leave information is presented to prospective residents and whether medical students want this information.

Methods

Fifty-two program directors (PD’s) at 3 sites of a single institution received a survey in 2019 to identify whether parental leave information is presented at residency interviews. Medical students received a separate survey in 2020 to identify their preferences. Fisher exact tests, Pearson χ2 tests and Cochran-Armitage tests were used where appropriate to assess for differences in responses.

Results

Of the 52 PD’s, 27 responded (52%) and 19 (70%) indicated that information on parental leave was not provided to candidates. The most common reason cited was the belief that the information was not relevant (n = 7; 37%). Of the 373 medical students, 179 responded (48%). Most respondents (92%) wanted parental leave information formally presented, and many anticipated they would feel extremely or somewhat uncomfortable (68%) asking about parental leave. The majority (61%) felt that these policies would impact ranking of programs “somewhat” or “very much.”

Conclusions

Parental leave policies may not be readily available to interviewees despite strong interest and their impact on ranking of programs by prospective residents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thousands of medical students interview for residency programs each year, and over 50% of medical students were women in 2019 [1]. The average age of US women having their first child is 26 years [2], which coincides with the beginning of residency for many trainees [3]. In a survey of 269 residency and fellowship programs, 40% of trainees indicated that they planned to have children during their graduate medical education (GME) [4].

A training program with a supportive culture can foster an ideal learning environment for residents [5]. Among residents planning to start or grow their family during training, the institution’s parental leave policy becomes an important part of the decision-making process when ranking residency programs [6]. The known benefits of paid parental leave include decreased infant mortality, improved physical and mental health for mother and infant, increased maternal participation in the labor force, and enhanced morale of parents [7,8,9,10]. However, parental leave policies vary widely between institutions [11]. In an analysis of the top 50 medical schools with affiliated GME programs, 42% had paid leave policies for residents and fellows (average duration, 5.1 weeks), 42% did not provide any paid leave, and 22% offered state-mandated, partially paid leave [12].

During residency interviews, presentations of parental leave policies may also vary, and prospective residents may not inquire directly about these policies despite their interest, because of perceived potential negative consequences. These fears of stigma are not unfounded. In various surveys of PD’s, 61–83% have reported a belief that becoming a parent during residency negatively affects the performance of female physicians [7, 13].

Family and lifestyle factors are among the most influential considerations for medical students as they plan their lives and careers [14], so it is important for parental leave policies to be presented uniformly and consistently during the interview process. We sought to investigate whether parental leave policies are presented during residency interviews and to evaluate whether medical students are interested in that information.

Methods

An electronic survey for PD’s was developed to determine whether parental leave policies were presented during residency interviews (Supplemental Digital Appendix 1). The voluntary electronic survey was emailed in November 2019 to all PD’s within our institution, with training sites in 3 states. PD’s were asked whether they addressed parental leave policies at interviews and why or why not. Multiple responses could be selected, and free text responses were later grouped according to similarity. Responses were compared by respondents’ sex and age (< 50 years or ≥ 50 years).

An electronic survey for medical students was created to determine whether parental leave policies were presented at residency interviews (Supplemental Digital Appendix 2). The voluntary electronic survey was emailed in June 2020 to medical students at our institution, which has 1 medical school and 3 sites. Results were analyzed according to sex, age, marital status, current parental status, and reproductive plans during residency.

Responses were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Fisher exact tests were used to assess for group differences in the responses from PD’s. Differences in responses from medical students were assessed with Pearson χ2 tests for nominal variables and Cochran-Armitage tests for Likert scale variables. In addition, Cramer’s V and Cliff’s Delta effect sizes were computed to show association strength for nominal variables and Likert scale variables respectively. Association strength based on Cramer’s V is considered negligible if less than 0.1; small if between 0.1 and 0.3; medium if between 0.3 and 0.5; and large if 0.5 or greater [15]. Association strength based on Cliff’s Delta is considered negligible if the magnitude is less than 0.147; small if between 0.147 and 0.33; medium if between 0.33 and 0.474; and large if 0.474 or greater [16]. Two-sided P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with R version 3.6 software (R Foundation) [17]. Institutional review was sought, and the project was deemed exempt.

Results

Of the 52 PD’s who were surveyed, 27 responded (52%). A majority (n = 19; 70%) indicated that parental leave was not addressed with candidates for reasons that included the following: information was not relevant (n = 7; 37%); candidates were not interested (n = 2; 11%); policy was addressed elsewhere (n = 4; 21%); residents should not have children during training (n = 1; 5%); policy was provided only upon request (n = 3; 16%); and insufficient time (n = 3; 16%) (Table 1). Presentation methods varied amongst the 8 PD’s who presented policy information and included slide presentation (n=4HR presentation (n=1) discussion if asked (n=4), discussed with all candidates (n=3). There were no statistically significant differences in PD’s responses when evaluated by sex or age.

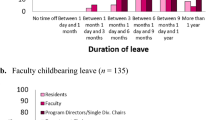

The medical student survey was sent to 373 students throughout all 4 years, and 179 responded (48%). Demographics are summarized in Supplemental Digital Appendix 3. Most respondents did not have children (n = 155, 87%). More than half (n = 111, 62%) anticipated that they or their partner would have a child during residency. The majority (n = 108, 92%) would appreciate having information related to parental leave formally presented at residency interviews. Many respondents reported that they would anticipate feeling at least somewhat uncomfortable (n = 119, 68%) asking about parental leave at an interview. Of those, 59% (n = 105) worried it would lessen their chance of acceptance. There was no consensus regarding whether or not they expect parental leave policies to be formally presented. When asked whether a parental leave policy would impact their ranking of programs, 78% (n = 135) responded that it would “somewhat” or “very much” affect their decision on ranking otherwise equivalent programs. When asked how they would like to receive information on parental leave policy, 76% (n = 133) desired formal presentation; 57% (n = 101) desired handouts during the interview; and 39% (n = 69) desired unofficial conversations. In regard to whether or not fourth-year students who had already interviewed (n = 24) received this information formally, 14 (58%) responded, “sometimes”; 8 (33%), “never”; and 2 (8%), “always.” When asked whether leave policies were informally discussed, 17 (71%) responded, “sometimes”; 5 (21%), “never”; and 2 (8%), “always.” When comparing respondents according to sex and response to the question “Do you anticipate you or your partner will have a child during residency,” significant differences were noted for several responses (Tables 2 and 3). Three respondents did not provide their sex in the survey and were excluded from Table 2 (n = 176). While the large majority of men and women indicated that they would appreciate formal presentation of parental leave information, women responded positively at a significantly higher rate (96% vs 84%; Cramer’s V = 0.25; P = 0.004). Women were significantly more uncomfortable asking the PD about information related to parental leave (80% vs 46%; Cliff’s Delta = -0.39; P < 0.001). A higher percentage of women also responded that these policies would impact their ranking of residency programs. Respondents who anticipated that they or their partner would have a child during residency reported that a difference in parental leave policy may somewhat (n = 42; 39%) or very much (n = 52; 48%) impact their ranking of 2 equivalent programs (Table 3). We found no significant differences in responses according to age, marital status, or current parental status.

Discussion

We found that nearly all residency applicants (92%) would prefer parental leave policies to be formally addressed during interview. Over 60% of respondents anticipated having a child during residency, thus making parental leave policies highly relevant. The discomfort expressed by medical students, highest amongst women, with asking about these policies is in direct contrast with the fact that 70% of PD’s responded that parental leave is not formally presented. 69% of women and 43% of men reported that they were worried asking about parental leave during the interview would lessen their chance of acceptance into the program. This discordance between applicants’ needs and current training program practice represents a gap and an opportunity. Some PD’s responded that if asked, they would address parental leave, unveiling the lack of awareness many may have regarding the comfort of medical students addressing these subjects.

In the 2017–2018 medical school application cycle, the average age of male and female applicants was 24 years, which positions most graduating medical students in their childbearing years during residency [3]. A survey of 705 medical students interested in family medicine residencies demonstrated that work-life balance was among the highest rated factors influencing residency selection [14]. Another survey of 644 residents and fellows found that approximately 40% planned to have children during their GME [4]. The same survey found that women were more likely than men to consider pregnancy and childbirth in their career decisions about GME programs, completion dates, and other degrees. In a survey of pediatric residents with children, over half of women and a third of men rated parental leave policies as very important in residency selection [18].

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) does not have a universal parental leave policy that must be followed by all GME programs [19]. The ACGME requires each GME program to have a leave policy according to their specialty board, but there is no clear consensus on how these policies should be presented or made available to applicants. This ambiguity presents a challenge for medical students who are considering childbearing during their GME. A study of the policies of 24 American Board of Medical Specialties organizations found that not all specialty boards outline family leave policies and that many policies have vague language [20]. Given the complexity of leave policies, clarification may be important to a large proportion of medical students, which is confirmed in our study.

Our findings suggest that parental leave policies should be presented formally to all candidates during the interview process to better address applicant needs, relieve the burden of having to ask and to mitigate the risk of negative bias toward applicants who want that information. More than half the surveyed medical students stated that parental leave policies would impact how they ranked programs, and would impact their decision if they were deciding between 2 equivalent programs. By formally presenting the information during interviews, PD’s can facilitate a better match and alignment of priorities for both the applicant and the program. As the number of women applying to medical schools increases, programs interested in attracting the best applicants would be wise to acknowledge the importance of parental leave policies to students who are ranking their programs.

Our study is limited by the small number of PD’s who responded and by the survey being conducted at a single institution. Larger multisite surveys of both PD’s and medical students may further elucidate the importance of parental leave policies on applicants’ selection of a residency program.

Conclusion

A gap exists between 1) medical student interest and comfort level with obtaining information about parental leave policies and 2) residency PD’s perception of the importance and relevance of this information. Parental leave policies are important to medical students interviewing for residency, but they may not be regularly shared or easily accessible. Parental leave policies and practices should be formally presented to all residency candidates before or during the interview process.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

25 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03114-2

Abbreviations

- ACGME:

-

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

- GME:

-

Graduate medical education

- PD:

-

Program director

References

Heiser S. The Majority of U.S. Medical Students Are Women, New Data Show Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019 [Available from: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/majority-us-medical-students-are-women-new-data-show.

Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Mean Age of Mothers is on the Rise: United States, 2000–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;232:1–8.

Association of American Medical Colleges. Table A-6: Age of Applicants to U.S. Medical Schools at Anticipated Matriculationby Sex and Race/Ethnicity, 2014–2015 through 2017–2018 2017 [Available from: https://www.aamc.org/system/files/d/1/321468-factstablea6.pdf.

Blair JE, Mayer AP, Caubet SL, Norby SM, O’Connor MI, Hayes SN. Pregnancy and Parental Leave During Graduate Medical Education. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):972–8.

Jennings ML, Slavin SJ. Resident Wellness Matters: Optimizing Resident Education and Wellness Through the Learning Environment. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1246–50.

Weaver AN, Willett LL. Is It Safe to Ask the Questions That Matter Most to Me? Observations From a Female Residency Applicant. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1635–7.

Hariton E, Matthews B, Burns A, Akileswaran C, Berkowitz LR. Pregnancy and parental leave among obstetrics and gynecology residents: results of a nationwide survey of program directors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):199 e1- e8.

Jou J, Kozhimannil KB, Abraham JM, Blewett LA, McGovern PM. Paid Maternity Leave in the United States: Associations with Maternal and Infant Health. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(2):216–25.

Nandi A, Jahagirdar D, Dimitris MC, Labrecque JA, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS, et al. The Impact of Parental and Medical Leave Policies on Socioeconomic and Health Outcomes in OECD Countries: A Systematic Review of the Empirical Literature. Milbank Q. 2018;96(3):434–71.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Paid Parental Leave. Statement of Policy Washington, D.C: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2020. (Available from: https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/policy-and-position-statements/statements-of-policy/2019/paid-parental-leave).

Wendling A, Paladine HL, Hustedde C, Kovar-Gough I, Tarn DM, Phillips JP. Parental Leave Policies and Practices of US Family Medicine Residency Programs. Fam Med. 2019;51(9):742–9.

Gottenborg E, Rock L, Sheridan A. Parental Leave for Residents at Programs Affiliated With the Top 50 Medical Schools. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(4):472–4.

Sandler BJ, Tackett JJ, Longo WE, Yoo PS. Pregnancy and Parenthood among Surgery Residents: Results of the First Nationwide Survey of General Surgery Residency Program Directors. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(6):1090–6.

Wright KM, Ryan ER, Gatta JL, Anderson L, Clements DS. Finding the Perfect Match: Factors That Influence Family Medicine Residency Selection. Fam Med. 2016;48(4):279–85.

Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Romano J, Kromrey JD, Coraggio J, Skowronek J, editors. Appropriate statistics for ordinal level data: Should we really be using t-test and Cohen’sd for evaluating group differences on the NSSE and other surveys. annual meeting of the Florida Association of Institutional Research; 2006.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018 [Available from: https://www.r-project.org/.

Berkowitz CD, Frintner MP, Cull WL. Pediatric resident perceptions of family-friendly benefits. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(5):360–6.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Policies and Procedures Chicago. Illinois: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2020. (Available from: http://www.acgme.org/portals/0/pdfs/ab_acgmepoliciesprocedures.pdf).

Varda BK, Glover Mt. Specialty Board Leave Policies for Resident Physicians Requesting Parental Leave. JAMA. 2018;320(22):2374–7.

Acknowledgements

N/A

Funding

Funding was provided by the Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic in Arizona, and funds were used to support the efforts of the statistician in analysis of the data. The funds did not support or play any role in study design, collection of data or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK, ER, JM, NS were major contributors in writing the manuscript. SBP performed all statistical analyses and provided major contribution to the writing of the manuscript. SH and JF played a major role in study design. LV and CS provided edits to all drafts of the manuscript. All authors provided editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: We correctly affiliated the authors: Jillian A. Maloney, Skye A. Buckner‑Petty and Natalie H. Strand. The affiliation address for the author Sharonne N. Hayes has been corrected.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Digital Appendix 1.

Program Director Survey on Parental Leave Policies at Residency Interviews

Additional file 2: Digital Appendix 2.

Medical Student Survey on Parental Leave Policies at Residency Interviews

Additional file 3: Digital Appendix 3.

Demographics of Medical Student Respondents

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kraus, M.B., Reynolds, E.G., Maloney, J.A. et al. Parental leave policy information during residency interviews. BMC Med Educ 21, 623 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03067-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03067-y