Abstract

Background

The application of manual emergency skills is essential in intensive care medicine. Simulation training on cadavers may be beneficial. The aim of this study was to analyze a skill-training aiming to enhance ICU-fellows´ performance.

Methods

A skill-training was prepared for chest tube insertion, pericardiocentesis, and cricothyroidotomy. Supervision levels (SL) for entrustable professional activities (EPA) were applied to evaluate skill performance. Pre- and post-training, SL and fellows´ self- versus consultants´ external assessment was compared. Time on skill training was compared to conventional training in the ICU-setting.

Results

Comparison of pre/post external assessment showed reduced required SL for chest tube insertion, pericardiocentesis, and cricothyroidotomy. Self- and external assessed SL did not significantly correlate for pre-training/post-training pericardiocentesis and post-training cricothyroidotomy. Correlations were observed for self- and external assessment SL for chest tube insertion and pre-assessment for cricothyroidotomy. Compared to conventional training in the ICU-setting, chest tube insertion training may further be time-saving.

Conclusions

Emergency skill training separated from a daily clinical ICU-setting appeared feasible and useful to enhance skill performance in ICU fellows and may reduce respective SL. We observed that in dedicated skill-training sessions, required time resources would be somewhat reduced compared to conventional training methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intensive care physicians should be familiar with emergency skill procedures such as chest tube insertion, pericardiocentesis and cricothyroidotomy. In environments with time constraints such as intensive care units, education may compete with clinical work and administrative responsibilities [1]. Therefore, educational concepts should be applied with specific and clear learning objectives [2]. Further, teaching and learning of technical skills in the ICU environment seems determined by caseload and, particularly for emergency skills, even more by suitable teaching cases in respective (emergency) situations. The transfer of training from the clinical setting to “safe environments” such as training on human cadavers in a wet lab may have beneficial effects on teaching/ learning experiences [3,4,5,6].

For previous familiarization with the theoretical content, the flipped classroom concept seems beneficial to focus on skill performance in subsequent trainings [7, 8]. In brief, in the flipped classroom concept, learners are familiarized to the educational content and in subsequent training they can apply new knowledge. In this concept, the andragogy theory of involves principles of adult learning [9]. Furthermore, the constructivism theory describes the learner as the architect of his own knowledge [10]. The flipped classroom concept ensures to adapt the volume of learning time, aligned by the learners’ needs and previous information.

Importantly, based on Simpson’s [11] and Harrow’s [12] taxonomy of psychomotor domains a technical skill are developed continuously over 5 stages: 1) guided response, imitation or try and error, 2) skills become habitual, 3) complex overt response, quick and accurate performance, 4) adaption with the ability to modify skill in difficult situations, 5) skill has mastered and new movements addressed unique situations and specific problems [13]. Especially for step one (with regard to emergency skills) “try and error” should be avoided in direct patient care and should thus be performed in simulated training.

Typically, skill training covers two phases with five steps: first, a cognitive phase: step 1) learning should be performed via reading and visualization (e.g. video) and step 2) viewing demonstration of skills [13, 14]. Phase two, the psychomotor phase, includes step 3) formative assessment on simulator training to deliberate practice, 4) summative assessment on simulator training and finally step 5) performance on patients [13, 14].

Secure performance on actual patients without need for direct supervision should thus be a key objective of skill training. Hence, skill training should have a positive effect on fellows’ performance and may increase trust to reduce subsequent supervision levels in daily practice. The aim of the current investigation was to analyze a new emergency skill training program to enhance the performance of ICU fellows. In particular, we were interested whether such a program would reduce supervision levels, based on external assessment.

Methods

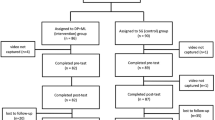

Participants

Participants of the new skill training program were ICU-fellows in a tertiary care academic hospital (Inselspital, University of Bern, Switzerland). Every year about 6500 patients are treated in our multidisciplinary Department of Intensive Care Medicine. The department compromises about 57 beds and treats all types of (multi) organ failures, including extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). ICU-fellows in this investigation are typically subjected to > 12 months of training in intensive care medicine. Within this training program, full day skill training was performed twice per year since 2017. Over this period, 31 ICU-fellows participated in the skill-training program and were invited to participate in this voluntary assessment that also aimed to assess the quality of the established training program. This assessment adheres to the declaration of Helsinki.

Educational concepts: design and setting

Learning objectives in this skill-training program consisted in skill technics considered highly relevant for emergency situations in the ICU setting: ICU-fellows were trained in chest tube insertion, pericardiocentesis, and cricothyroidotomy. Training on human cadavers was performed in the laboratory of the Institute of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Bern, Switzerland. Cadaver training was designed to improve confidence in the skill performance [4, 5, 15,16,17,18,19]. Particular for emergency skill training, and when compared to artificial skill-simulators, cadavers may provide improved learning experiences [4,5,6]. Pre-training, all fellows received literature and video documents along with the departmental standard operating procedures (SOP), including previously published articles/ video training [20,21,22,23]. Fellows prepared the obtained learning material individually prior to skill training. A maximum of six fellows with two experienced attending consultants (teachers) applied in an effort to maximize learning experiences and provide best individual support [24]. Formative assessment during training was performed to enhance fellows’ skill performance. A summative assessment was performed with the consultants’ post-training assessment of required supervision levels to determine future required supervision levels for daily ICU work.

Assessment of fellows’ self- and external perception

The five supervision levels are based on Ten Cates´ levels for entrustable professional activities [25]. In brief, supervision levels are defined as followed: 1) Observation but not execution, even with direct supervision, 2) execution with direct, proactive supervision, 3) execution with reactive supervision, i.e., on request and quickly available, 4) supervision at a distance and/or post hoc and 5) supervision provided by the trainee to colleagues [25]. Participating fellows assess their expected supervision level for each skill before and after skill trainings. Based on observations in daily clinical setting prior the training, teaching consultants assessed required supervision levels of each skill for each individual fellow. After skill training, consultants re-assessed supervision levels for each skill of each individual fellow.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc 17.4 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare pre- and post-training (perceived) supervision levels. Spearman rank correlations were used to compare fellows´ and consultants´ perceptions of supervision level. A descriptive analysis was aimed for. A two-tailed p-value < 0.5 was considered significant.

Results

Data from self-assessment surveys (expected supervision levels of respective skill) was available in 94% (29/31) of cases.

Assessment of chest tube insertion

Results of pre−/ post-training self- and external assessment are given (Table 1A). Self-assessment of 21 fellows (21/29, 72%) rated a positive difference between pre- and post-training supervision (“Execution with reactive supervision, i.e., on request and quickly available” to “supervision at a distance and/or post hoc”, p < 0.0001). External assessment rated 25 fellows (25/29, 86.21%) with an improvement on their required supervision levels (median change from “Execution with direct, proactive supervision” to “Supervision at a distance and/or post hoc”, p < 0.0001, Fig. 1). Self- and external assessed pre-training/post-training supervision levels were observed to correlate (r = 0.65, 95%-CI 0.37–0.82, p = 0.0002; r = 0.46, 95%-CI 0.1–0.71, p = 0.01, respectively).

Assessment of pericardiocentesis

Results of pre−/ post-training self- and external perception are given in Table 1B. Twenty-six fellows (26/29, 90%) rated a positive effect on their expected supervision level (“Observation but not execution, even with direct supervision” to “execution with direct, proactive supervision”, p < 0.0001). External assessment rated 29 fellows (100%) with a positive change in their required supervision level (median change from “Observation, but not execution, even with direct supervision” to “Execution with reactive supervision, i.e., on request and quickly available”, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2). Self- and external assessed pre-training/post-training supervision level did not significantly correlate (n.s.).

Assessment of cricothyroidotomy

Results of pre- /post-training perception of self and external are given in Table 1C. Twenty-two fellows (22/29, 76%) rated a positive effect on their expected supervision level (“Observation but not execution, even with direct supervision” to “execution with reactive supervision, i.e., on request and quickly available”, p < 0.0001). External assessment rated 29 fellows (100%) with a positive change in their supervision level (median change from “Observation but not execution, even with direct supervision” to “Execution with reactive supervision, i.e., on request and quickly available”, p < 0.0001, Fig. 3). Self-assessment of the fellows expected supervision pre-training supervision level correlated significantly with the external assessment of the required supervision level (r = 0.41, p = 0.03, 95%-CI 0.06–0.68). Post-training self- and external assessment of supervision level was not observed to significantly correlate (n.s.).

Expenditure of time for emergency skill training versus clinical teaching

The part of chest tube insertion in the skill training required about two hours, in which every fellow had the opportunity to perform 6–8 chest tube insertions. In total, about 12 h (6 fellows x about 2 h) of working time applied for chest tube insertion training. For attending consultants, about 4 h of working time was required for the chest tube insertion training (about 2 × 2 h). In comparison, the time for teaching in a daily ICU-setting for each chest tube insertion required would typically be an estimated 30 min (minimum). Hence, six chest tube insertions for each fellow (about 30 min × 6 = 180 min), for six fellows (about 180 min × 6 fellows) require 1080 min (18 h) of time on supervision. During respective supervision activities, the attending consultant would be absorbed and unable to perform other activities. Hence, potential time saving for attending consultants might be about 12 h.

Discussion

The application of emergency skills is essential in intensive care medicine. In this assessment of a newly developed training program, trust and performance was measured according to Ten Cates’ EPA levels of supervision [25]. We deliberately combined formative and summative (external) assessments to increase fellows’ performance during the training [26] and required supervision levels, respectively [13, 14]. Our observations suggest that a full day skill training may increase the ability of ICU-fellows to perform technical emergency skills such chest tube insertion, pericardiocentesis and cricothyroidotomy based on the (somewhat subjective) determination of supervision levels. Further, the opportunity to repeat respective skills during training [11, 12] and to receive feedback [27] may additionally support respective skills. The repeated practical exercise may seem key to obtain confidence and proficiency [13].

Self-assessments of ICU fellows showed a positive progression in all skills. Accurate self-assessment or self-perception of confidence and/or competence is key to ensure a sufficient learning process [28]. However, self-assessment has several limitations and may not reflect actual, i.e. objective performance [29,30,31]. Self-deception, i.e. lack of insight into one’s incompetence and reduced impression management [32] may limit valid self-assessment. Despite these limitations, self-assessed progression may spark the fellows’ interest and likely increase their motivation. This motivation may be key for education in ICU-residents [2] and may result in increased performance [33, 34]. Interestingly, improved learners’ (fellows) skill competence helped to acknowledge skill limitations and may lead to lower ratings in respective self-assessments [29]. Evaluating self-perceived skill competence may provide learner motivation in improving respective skills, and this may be crucial in self-efficacy regarding learning [35].

Despite the known limitations of self-assessment, for chest tube insertion self- and external assessment, expected/ required supervision levels correlated significantly. However, differences were observed in pre- and post-assessment for self and external assessment as noted for pericardiocentesis. Interestingly, post-training external assessment showed better improvement in performance (regarding supervision levels) when compared to ICU fellows’ self-assessment, which may be due to several reasons. Feedback and formative assessment during the skill training may increase skill performance without better self-perception, reduced self-deception and increased impression management [31, 36, 37]. Inadequate feedback [38] or fellows’ information neglect and memory bias may influence self-assessment [31]. Experienced fellows impression management may decrease, and self-assessment may be comparable to external assessment [31], which may open new avenues for future investigations.

Congruent pre-training self- and external assessment, as observed for cricothyroidotomy, changed into biased post self and external assessment for supervision levels. This seems in line with previous findings [29, 30] and may be explained by a realistic impression management prior to skill training due to prior experience/ training. The difference in post-training assessment may be caused by increased self-deception after the skill trainings.

Limitations

This analysis has several additional important limitations that deserve discussion, including a limited sample size. Further, a monocentric observational investigation applied, with all inherent limitations driven by design of the investigation. Hence, an interpretation of the data should only be done with caution and further investigations with larger sample-sizes should be performed to enhance external validity. In addition, external assessment of fellows’ performance was not carried out using checklists and inter-individual assessment bias may apply. However, external assessment focused on adherence to correct technical performance as outlined in the pre-training preparation literature (including videos). However, checklists for procedural skills may be incomplete even regarding key components [39]. Future investigations should thus address conditions of changes in supervision levels related to distinct respective competencies as in the current literature this currently remains elusive. Additionally, we defined pre- and post-training external supervision levels by internal consultants’ discussion and consensus; hence no inter-rater reliability was assessed. Furthermore, we focused on short-term benefits of this skill training and data on long-term effects of this training are therefore not available. Importantly, retention of emergency skills is time-depended with training and repetition (e.g. every 6 months) likely required to sustain performance of emergency skills [40]. Further, focus of this investigation was on chest tube insertion, pericardiocentesis, and cricothyroidotomy as they may be regarded highly relevant and complex technical skills. Due to application in acute emergency situations, cost-benefit was not considered for pericardiocentesis and cricothyroidotomy. Moreover, chest tube insertion training appeared time saving when compared to traditional ICU-training approaches. However, as no standardized environment applied, this should be pursued in subsequent studies also.

Conclusions

In ICU fellows, emergency skill training separated from daily clinical ICU-setting appeared useful to enhance learning experiences, skill performance, and levels of trust. Despite observed differences in self-reported and external assessments, external assessment of ICU-fellows observed a positive progression of performing emergency skills and led to reduced supervision levels.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this publication article.

Abbreviations

- ICU:

-

Intensive Care Unit

- SL:

-

Supervision level

- EPA:

-

Entrustable professional activity

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

References

Joyce MF, Berg S, Bittner EA. Practical strategies for increasing efficiency and effectiveness in critical care education. World J Crit Care Med. 2017;6(1):1–12.

Zante B, Hautz WE, Schefold JC. Physiology education for intensive care medicine residents: a 15-minute interactive peer-led flipped classroom session. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0228257.

Kovacs G, Levitan R, Sandeski R. Clinical cadavers as a simulation resource for procedural learning. AEM education and training. 2018;2(3):239–47.

Tabas JA, Rosenson J, Price DD, Rohde D, Baird CH, Dhillon N. A comprehensive, unembalmed cadaver-based course in advanced emergency procedures for medical students. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(8):782–5.

Ferguson IM, Shareef MZ, Burns B, Reid C. A human cadaveric workshop: one solution to competence in the face of rarity. Emergency Med Australasia : EMA. 2016;28(6):752–4.

Takayesu JK, Peak D, Stearns D. Cadaver-based training is superior to simulation training for cricothyrotomy and tube thoracostomy. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12(1):99–102.

Chiu HY, Kang YN, Wang WL, Huang HC, Wu CC, Hsu W, et al. The effectiveness of a simulation-based flipped classroom in the Acquisition of Laparoscopic Suturing Skills in medical students-a pilot study. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(2):326–32.

Glass CC, Parsons CS, Raykar NP, Watkins AA, Jinadasa SP, Fleishman A, et al. An effective multi-modality model for single-session cricothyroidotomy training for trainees. Am J Surg. 2019;218(3):613–8.

Knowles MS, Swanson RA. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. 7th ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2011.

Brandon AF, All AC. Constructivism theory analysis and application to curricula. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2010;31(2):89–92.

Simpson E. The classification of educational objectives in the psychomotor domain. Washington, DC: Grypohn House; 1972.

Harrow A. A taxonomy of the psychomotor domain. New York, NY: David McKay; 1972.

Sawyer T, White M, Zaveri P, Chang T, Ades A, French H, et al. Learn, see, practice, prove, do, maintain: an evidence-based pedagogical framework for procedural skill training in medicine. Acad Med. 2015;90(8):1025–33.

Kovacs G. Procedural skills in medicine: linking theory to practice. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(3):387–91.

Yiasemidou M, Gkaragkani E, Glassman D, Biyani CS. Cadaveric simulation: a review of reviews. Ir J Med Sci. 2018;187(3):827–33.

Gunst M, O'Keeffe T, Hollett L, Hamill M, Gentilello LM, Frankel H, et al. Trauma operative skills in the era of nonoperative management: the trauma exposure course (TEC). J Trauma. 2009;67(5):1091–6.

Ferrada P, Anand RJ, Amendola M, Kaplan B. Cadaver laboratory as a useful tool for resident training. Am Surg. 2014;80(4):408–9.

Bowyer MW, Kuhls DA, Haskin D, Sallee RA, Henry SM, Garcia GD, et al. Advanced surgical skills for exposure in trauma (ASSET): the first 25 courses. J Surg Res. 2013;183(2):553–8.

Kim SC, Fisher JG, Delman KA, Hinman JM, Srinivasan JK. Cadaver-based simulation increases resident confidence, initial exposure to fundamental techniques, and may augment operative autonomy. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(6):e33–41.

Dev SP, Nascimiento B Jr, Simone C, Chien V. Videos in clinical medicine. Chest-tube insertion. New England J Med. 2007;357(15):e15.

Regli B, Mende L. Thoraxdrainge. Die Intensivmedizin. Berlin: Springer; 2011.

Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, et al. Difficult airway society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(6):827–48.

Fitch MT, Nicks BA, Pariyadath M, HD MG, Manthey DE. Videos in clinical medicine. Emergency pericardiocentesis. New England J Med. 2012;366(12):e17.

Loewen P, Legal M, Gamble A, Shah K, Tkachuk S, Zed P. Learner : preceptor ratios for practice-based learning across health disciplines: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2017;51(2):146–57.

Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Graduate Med Educ. 2013;5(1):157–8.

Lorwald AC, Lahner FM, Nouns ZM, Berendonk C, Norcini J, Greif R, et al. The educational impact of mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) and direct observation of procedural skills (DOPS) and its association with implementation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198009.

Boehler ML, Rogers DA, Schwind CJ, Mayforth R, Quin J, Williams RG, et al. An investigation of medical student reactions to feedback: a randomised controlled trial. Med Educ. 2006;40(8):746–9.

Roland D, Matheson D, Coats T, Martin G. A qualitative study of self-evaluation of junior doctor performance: is perceived 'safeness' a more useful metric than confidence and competence? BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e008521.

Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121–34.

Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. Jama. 2006;296(9):1094–102.

Zevin B. Self versus external assessment for technical tasks in surgery: a narrative review. Journal of graduate medical education. 2012;4(4):417–24.

Evans AW, Leeson RM, Newton John TR, Petrie A. The influence of self-deception and impression management upon self-assessment in oral surgery. Br Dent J. 2005;198(12):765–9 discussion 55.

Robbins SB, Lauver K, Le H, Davis D, Langley R, Carlstrom A. Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychol bull. 2004;130(2):261–88.

Kusurkar RA, Ten Cate TJ, van Asperen M, Croiset G. Motivation as an independent and a dependent variable in medical education: a review of the literature. Medical teacher. 2011;33(5):e242–62.

Lai NM, Teng CL. Self-perceived competence correlates poorly with objectively measured competence in evidence based medicine among medical students. BMC medical education. 2011;11:25.

McKenzie S, Burgess A, Mellis C. Interns reflect: the effect of formative assessment with feedback during pre-internship. Advances Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:51–6.

Ramani S, Konings K, Mann KV, van der Vleuten C. Uncovering the unknown: a grounded theory study exploring the impact of self-awareness on the culture of feedback in residency education. Med teacher. 2017;39(10):1065–73.

Eva KW, Regehr G. “I'll never play professional football”: and other fallacies of self-assessment. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2008;28(1):14–9.

McKinley RK, Strand J, Ward L, Gray T, Alun-Jones T, Miller H. Checklists for assessment and certification of clinical procedural skills omit essential competencies: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2008;42(4):338–49.

Ansquer R, Mesnier T, Farampour F, Oriot D, Ghazali DA. Long-term retention assessment after simulation-based-training of pediatric procedural skills among adult emergency physicians: a multicenter observational study. BMC medical education. 2019;19(1):348.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Consent of publication

Not applicable.

Funding

For this study no funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BZ and JCS analyzed and interpreted the data. BZ and JCS drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JCS and BZ (full disclosure) report grants from Orion Pharma, Abbott Nutrition International B. Braun Medical AG, CSEM AG, Edwards Lifesciences Services GmbH, Kenta Biotech Ltd., Maquet Critical Care AB, Omnicare Clinical Research AG, Nestle, Pierre Fabre Pharma AG, Pfizer, Bard Medica S.A., Abbott AG, Anandic Medical Systems, Pan Gas AG Healthcare, Bracco, Hamilton Medical AG, Fresenius Kabi, Getinge Group Maquet AG, Dräger AG, Teleflex Medical GmbH, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck Sharp and Dohme AG, Eli Lilly and Company, Baxter, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, CSL Behring, Novartis, Covidien, and Nycomed outside the submitted work. The money was paid into departmental funds. No personal financial gain applied.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zante, B., Schefold, J.C. Simulation training for emergency skills: effects on ICU fellows’ performance and supervision levels. BMC Med Educ 20, 498 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02419-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02419-4