Abstract

Background

Resilience refers to the ability to be flexible and adaptive in response to challenges. Medical students in clerkship who are transitioning from medical studies to clinical practice face a variety of workplace demands that can lead to negative learning experiences and poor quality of life. This study explored whether medical students’ resilience plays a protective role against the stresses incurred during workplace training and on their professional quality of life during clerkships.

Methods

This was a 1-year prospective web-based questionnaire study comprising one cohort of medical students in their fifth year who were working as clerks as part of their 6-year medical education programme at one medical school in Taiwan between September 2017 and July 2018. Web-based, validated, structured, self-administered questionnaires were used to measure the students’ resilience at the beginning of the clerkship and their perceived training stress (i.e. physical and psychological demands) and professional quality of life (i.e. burnout and compassion satisfaction) at each specialty rotation. Ninety-three medical students who responded to our specialty rotation surveys at least three times in the clerkship were included and hierarchical regressions were performed.

Results

This study verified the negative effects of medical students’ perceived training stress on burnout and compassion satisfaction. However, although the buffering (protective) effects of resilience were observed for physical demands (one key risk factor related to medical students’ professional quality of life), this was not the case for psychological demands (another key risk factor). In addition, through the changes in R square (∆R2) values of the hierarchical regression building, our study found that medical students’ perceived training stresses played a critical role on explaining their burnout but their resilience on their compassion satisfaction.

Conclusions

Medical students’ resilience demonstrated a buffering effect on the negative relationship between physical demands and professional quality of life during clerkships. Moreover, different mechanisms (predictive paths) leading to medical students’ professional quality of life such as burnout and compassion satisfaction warrant additional studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Resilience refers to the ability of people to ‘bounce back’ when they encounter difficulties [1]. These difficulties can range from adversities to traumas, tragedies, and threats; these can even be significant sources of stress, such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems, or workplace and financial stresses [2]. Resilience is viewed as a flexible and adaptive act performed in response to challenges or an aggregate concept of multiple qualities, both of which indicate an ability to survive and address the likely consequences of handling pressure or adversity [3]. Although medical students’ resilience has not been found to be related to their academic course performance [4], the role of resilience has been shown to be positively associated with the well-being of medical students. For instance, previous cross-sectional questionnaire studies have revealed associations between medical students’ resilience and their lower levels of psychological distress [4], better life satisfaction [5, 6], happiness [5], higher quality of life [7], fewer anxiety symptoms [8], and increased subjective well-being [9, 10]. However, one study in Canada revealed that medical students had higher perceived stress, poorer coping skills, and lower resilience than age- and gender-matched peers in the general population [11].

One study argued that medical students face numerous stressors during their study curricula, which require adequate resilience to ensure healthy adaptation [12]. In particular, medical students experience considerable challenges in their learning experiences and career development when they transit from the classroom to clinical environments or progress from the position of junior resident to attending physician. Whether before or after graduation, undergoing clinical training is more challenging than studying at school and can trigger many physical and mental health conditions (particularly mental disorders and emotional exhaustion) in medical students [13]. Studies have also revealed that medical students can encounter stressful clinical events [14] and psychological and physical demands [15, 16] during their clinical training years. A review study covering the peer-reviewed, English-language articles in MEDLINE between 1990 and 2015 revealed a prevalence of burnout among trainees, including medical students, residents, and interns, to a much higher level than found among the general population [17]. Another study indicated that medical students should be equipped with not only medical knowledge but also an awareness of how to properly care for themselves [13].

Resilience is viewed as a way for individuals to manage stress, survive competently, and engage in learning despite mental pressures [18], therefore, our study explored whether medical students’ resilience could play a protective role in workplace training stress and professional quality of life during clerkships. Our specific hypotheses are as follows:

- (1)

Medical students’ workplace training stress is negatively related to their professional quality of life during clerkships.

- (2)

If Hypothesis 1 is true, medical students’ resilience is a protective factor that buffers the negative relationship between their workplace training stress and professional quality of life.

Methods

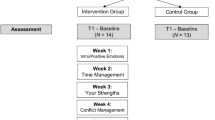

This was a 1-year non-experimental, prospective web-based questionnaire study.

Participants

Our study comprised one cohort of medical students undergoing their clerkships during their fifth year of a 6-year medical education programme at one medical school in Taiwan between September 2017 and July 2018. In Taiwan, medical students undergoing clerkships are equivalent to third- or fourth-year students undergoing clinical training in 4-year graduate medical programmes in western countries. One recruitment meeting of approximately 20 min was held during the students’ pre-clerkship courses, 1 week before the start of their clerkships. Of 199 medical students, 151 (75.9%) agreed to participate in the study and provided written informed consent.

Instrument development and administration

Structured and self-administered questionnaires were used in this study, consisting of the following measures:

Resilience of medical students

Resilience was measured using the 14-item Resilience Scale, with each item evaluated on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) [19]. Principal components factor analysis was performed, and one common factor was constrained. One item (‘self-discipline is important’) with a factor loading of < 0.4 was deleted [20]. A confirmatory factor analysis was then used to verify the items (p < .05) with an asymptotically distribution-free bootstrap model [21, 22] for construct validity testing and yielded moderate model fit. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.874. Finally, the resilience score of 13 items was calculated by the mean for further analysis. Detailed information is listed in Table 1.

Training stress of medical students in individual specialty rotations

By using Karasek’s Job Demands–Control model of job strain, stress during clinical training was measured through 10 items adapted from the Job Content Questionnaire, with the responses evaluated on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) [23]. Two stress constructs, namely psychological and physical demands, were extracted [15]. Psychological demands referred to mental workloads such as hard work, fast-paced work environment, busy at work, not enough sleeping time, work fatigue and intense work concentration, whereas physical demands referred to physical loads including physical positions, activities and loads [24]. Factor analysis revealed that the psychological (six items) and physical (four items) demands had factor loadings of 0.74–0.84 and 0.87–0.93, respectively. Confirmatory factor analyses was then used to verify the items (p < .05) with an asymptotically distribution-free bootstrap model [21, 22] for construct validity testing and yielded good model fit. The Cronbach’s alpha for psychological and physical demands was 0.903 and 0.942, respectively (Table 2). Detailed information is listed in Table 2. Factor scores for both psychological and physical demands were calculated using a regression model for further analysis [15].

Medical students’ professional quality of life in individual specialty rotations

The medical students’ professional quality of life during their clerkships was measured through burnout and compassion satisfaction items using the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL), Version V [25]. The ProQOL contains questions on the positive and negative effects of working with individuals who have experienced stress [26]. The ProQOL is offered in several languages, and the Chinese version was used in this study with one minor modification: the original word ‘helper’ was replaced with ‘medical doctor’ to better match the medical students’ scenarios.

Burnout is a negative emotion associated with feelings of difficulty and hopelessness in managing work or performing a job effectively [27]. In this study, it was evaluated using 10 questions inquiring how frequently the medical students experienced various emotions related to burnout, with five possible responses: 1 (never), 2 (seldom), 3 (sometimes), 4 (often), and 5 (always) [27]. A confirmatory factor analysis was used to verify the items (p < .05) with an asymptotically distribution-free bootstrap model [21, 22] for construct validity testing and yielded moderate model fit. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.854. One burnout score of 10 items was calculated by the mean for further analysis.

Compassion satisfaction refers to positive feelings about people’s ability to help and is characterised by a feeling of satisfaction with one’s job and from helping itself, feeling invigorated by the work that one likes to do, feeling that one can keep up with new technology and protocols, experiencing positive thoughts, feeling successful, being happy with the work one does and wanting to continue doing it, and believing that what one does makes a difference [27]. In this study, it was evaluated using 10 questions inquiring how frequently the medical students experienced various emotions related to compassion satisfaction, with five possible responses: 1 (never), 2 (seldom), 3 (sometimes), 4 (often), and 5 (always) [27]. A confirmatory factor analysis was used to verify the items (p < .05) with an asymptotically distribution-free bootstrap model [21, 22] for construct validity testing and yielded good model fit. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.960. One compassion satisfaction score of 10 items was calculated by the mean for further analysis.

Detailed information is presented in Table 1.

Medical student demographics

The medical students’ sex and age were included as partially confounding factors for training stress [15] and resilience [26].

Data collection

The medical students first completed a baseline survey that collected their demographic information and measured their resilience at the beginning of the clerkship. Subsequently, they regularly answered our surveys at each specialty rotation, providing their self-perceptions of training stress and professional quality of life. Because all of the medical students were free to decide whether to complete our surveys each time, each participant presented various responses during the study period. The medical students who submitted at least three responses to complete our individual rotating specialty surveys were included in this study. In total, 93 medical students with a total of 1073 responses were included.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to examine the medical students’ demographics, level of resilience, and perceived training stress and professional quality of life during their clerkships. It might be argued that the data in this study could be analysed using a two-level or multilevel analysis if variations were present in the medical students’ repeated responses regarding their burnout and compassion satisfaction at various specialty rotations with respect to their demographics and contexts. However, the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the medical students’ burnout (ICC = 0.00259) and compassion satisfaction (ICC = 0.00356) at individual specialty rotations were < 0.05, the minimum cutoff point to perform multilevel analysis [28, 29]. Thus, multilevel effects were ignored in this dataset.

The 1073 responses to the individual rotating specialty surveys from the 93 medical students was set as the unit of analysis by which to examine the effects of perceived training stress as risk factors on professional quality of life, and the moderating effect of the medical students’ resilience was verified through hierarchical regressions [30, 31]. Two hierarchical regressions were performed for each of the dependent variables, namely burnout and compassion satisfaction. For each hierarchical regression, the medical students’ personal characteristics such as sex and age were entered into the model at the first step. The risk factors of the medical students’ perceived training stress, measured by psychological and physical demands (factor scores), were included at the second step. At the third step, the medical students’ resilience, recalculated by mean-centred for ensuring the normality of distribution, was entered as a protective factor to test its direct effect. Finally, at the fourth step, the interaction terms of the medical students’ resilience (mean-centred) and perceived psychological and physical demands in training (factor scores) were included. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (version 18.0).

Results

Ninety-three medical students (43 men [46%] and 50 women [54%]; average age: 23 years) were included in our study. The medical students’ average resilience score measured at the beginning of their clerkships was 5.494 on average (SD = 0.735), with the items ‘I usually take things in stride’ and ‘I feel proud of having accomplished things in life’ having the lowest (mean = 4.000, SD = 1.460) and highest (mean = 6.151, SD = 0.955) scores, respectively. Detailed personal background information is listed in Table 1.

A review of the medical students’ 1073 responses to the individual specialty rotation surveys revealed that on average, the training stress perceived by the medical students was 2.696 (SD = 0.883) for psychological demands and 1.810 (SD = 0.819) for physical demands, whereas the average perceived professional quality of life was 2.346 (SD = 0.613) for burnout and 3.505 (SD = 0.815) for compassion satisfaction. Detailed descriptive analyses of the medical students’ perceived stress and professional quality of life on the basis of individual specialty rotations are presented in Table 2.

One hierarchical regression (unit of analysis = 1073 individual specialty rotation survey responses) was performed to test the buffering effect of the medical students’ resilience on the influence of stress on burnout during clinical training. The results revealed that the medical students’ perceived training stress, assessed in terms of psychological (β = 0.234, p < .001) and physical (β = 0.394, p < .001) demands, was related to increased burnout (Hypothesis 1, Step 2, Table 3) and that their resilience had a direct effect on reducing that burnout (β = − 0.350, p < .001) (Step 3, Table 3). Moreover, the results indicated that the medical students’ resilience buffered the negative effects of perceived training stress on their burnout in terms of physical (β = 0.104, p < .001) but not psychological (p > .05) demands (Hypothesis 2, Step 4, Table 3).

Another hierarchical regression (unit of analysis = 1073 individual specialty rotation survey responses) was performed to test the buffering effect of the medical students’ resilience on the influence of stress on their compassion satisfaction during clinical training. The results revealed that the medical students’ perceived training stress was associated with a lower degree of compassion satisfaction in terms of physical (β = − 0.226, p < .001) and psychological (β = − 0.072, p < .05) demands (Hypothesis 1, Step 2, Table 4). In addition, the medical students’ resilience had a direct effect on increased compassion satisfaction (β = 0.384, p < .001; Step 3, Table 4) and could buffer the negative effects of perceived training stress on their compassion satisfaction with regard to physical (β = − 0.092, p < .01) but not psychological (p > .05) demands (Hypothesis 2, Step 4, Table 4).

Discussion

In this prospective study, 1073 questionnaire responses from 93 medical students undergoing their 1-year clerkship were analysed to determine the negative effects of perceived training stress on burnout and compassion satisfaction (Hypothesis 1). In addition, resilience was observed to moderate the physical demands that impacted the medical students’ professional quality of life, but not the psychological demands (Hypothesis 2).

Our study confirmed the effect of training stress on increased medical student burnout, as reported in other studies [7, 15, 32]. In particular, our study revealed that the medical students’ physical demands (β = 0.394, p < .001) had a larger effect on their burnout risk than did their psychological demands (β = 0.234, p < .001; Table 3). Physical demands were measured by four items, namely awkward arm position, awkward body position, rapid physical activity, and lifting a heavy load. Based on our findings regarding the challenging physical demands that medical students face, which were skills-oriented and had a substantial influence on the medical students’ risk of burnout during clerkship, we suggest that further efforts should be made to explicitly target the needs of medical students with clear objectives and learning activities tailored to them, as well as student and course evaluations on a cycle-by-cycle basis for continuous teaching improvement and support [33].

Psychological demands were measured by six items, namely being demanded to hard work, a fast-paced work environment, being busy at work, a lack of sleep, work fatigue, and intense work concentration. Studies have found that the main stresses for medical students during their clerkships are applying clinical knowledge, learning experientially, using clinical skills, adjusting to clinical settings, and understanding roles [32, 33], as well as trauma exposure [34]. A supportive learning environment, including social supports, can have both direct [7] and moderating effects on the negative influence of stress on medical students’ mental health [35]. Supervision refers to the monitoring, guidance, and feedback by physicians in the patient care setting and is performed to ensure individual, professional, and educational development [36]. We might argue that given the psychological demands on medical students, adequate supervision by physicians or experts in various specialties is crucial to students’ successful clinical learning with regards to thinking patterns, decision-making protocols, and activities involved in patient care. Supervision would help medical students learn efficiently and effectively and would alleviate the effects of the mental demands required in their workplace [37].

In this study, compassion satisfaction referred to how the medical students perceived their training as medical doctors and how satisfied they felt about this profession during their clerkships. Our study revealed that the physical (β = − 0.226, p < .001) and psychological (β = − 0.072, p < .05) demands perceived by the medical students were related to reduced compassion satisfaction. Studies have revealed that physical demands resulting in physical complaints are made by physicians of both surgical and nonsurgical specialties [38]. In addition, a population-based 7-year longitudinal follow-up study in Denmark revealed that high physical work demands had an effect on subsequent unemployment, sick leave, and permanent work disability [39]. We might argue that medical students, as novices in medical practice, experience greater physical demands resulting from their lack of efficiency or familiarity with the workload, leading to frustration in learning and reducing their compassion satisfaction. Skill-based clinical apprentice training, covering the cognitive phase through various pedagogical approaches (e.g. instructive training, case studies, video teaching, and clinical practice) [40], followed by the psychomotor phase whereby learners practice their skills [41, 42], should be emphasised. Moreover, medical students should be assisted in cultivating procedural and technical skills to overcome the physical demands of clinical training, including planning, procedural demonstrations, learner observation, feedback, self-assessment, practice, and approach modification [43].

In this study, the medical students’ baseline resilience was measured at the beginning of their clerkship. Our results revealed that resilience was related to reduced burnout and increased compassion satisfaction during clinical training (Step 3, Tables 3 and 4). Resilience has been proposed as a valuable construct underpinning positive coping strategies for learning and professional practice [44]. A conceptual model coined as ‘the coping reservoir’ was proposed to encompass the inputs gained by students practising medicine [13], including educational and environmental supports (e.g. psychosocial support, social and health activities, and mentorship) [13], as well as mindfulness-based stress-reducing interventions [32, 45]. All of these are key issues that should be further explored when studying the determinants of medical students’ resilience.

Here, our examination of the buffering role of resilience on medical students’ stress on their professional quality of life (Step 4, Tables 3 and 4) revealed that the buffering effects of resilience were observed for physical demands (one risk factor for the medical students’ professional quality of life), but not for psychological demands (another risk factor). Resilience is described as an adaptive capability that originates from the interaction between individuals and their immediate environments [46,47,48]. Notably, the physical demands measured in our study were more task-, technical-, or skill-related, and it might have been easier for the students to ‘bounce back’ from these demands in the short run (i.e. during their first year of clerkship), than it might be for them to adapt to the psychological demands in the long run. Future longitudinal tracing research should be conducted to explore this. Future studies could also focus on strategies based on the identified influencers to assist medical students in clerkships for psychological demands.

Regarding the determinants of the medical students’ burnout and compassion satisfaction results, we found that changes in R square (∆R2) values for burnout determinants from Steps 1 to 4 demonstrated that training demands are a risk factor (Steps 1 and 2, ∆R2 = 0.210) that explain a larger variance than does resilience as a protective factor (Steps 2 and 3, ∆R2 = 0.110) in workplace training during clerkship (Table 3). However, changes in ∆R2 values for compassion satisfaction determinants from Steps 1 to 4 showed that resilience is a protective factor that explains a larger variance (Steps 2 and 3, ∆R2 = 0.135) than does training stress as a risk factor (Steps 1 and 2, ∆R2 = 0.057) in workplace training during clerkship (Table 4). With our limited data, different mechanisms (predictive paths) leading to medical students’ professional quality of life such as burnout and compassion satisfaction would be expected for additional studies in the future.

Several limitations of this study must be mentioned. First, only one cohort of medical students from one medical school was examined. Second, the stress experienced by the medical students in clinical training was measured according to workplace training demands. However, the sources of stress may vary and include problems such as poor team dynamics, witnessing a patient’s suffering or death, personal mistreatment, or poor role modelling by physicians [14, 34]. Third, the resilience level of medical students was measured at the beginning of their clerkships, whereby it was implicitly assumed that resilience would remain stable. However, resilience is variable and achievable [49] and serves as a criterion for self-adaptability [50]. Future studies could thus explore the dynamics of resilience levels in medical students. Supportive learning environments may have positive effects on the development of resilience among medical students in clinical training [51]. Moreover, various cultural norms could be an issue when identifying factors related to medical students’ resilience [52, 53].

Conclusions

With a prospective cohort design, this study analysed 1073 questionnaire responses of 93 medical students during their 1-year clerkship. Our study verified the negative effects of the students’ perceived training stress on burnout and compassion satisfaction. While resilience was the moderate the effects of physical demands (one risk factor for the medical students’ professional quality of life), it did not moderate the effects of psychological demands (another risk factor). Moreover, different mechanisms (predictive paths) leading to medical students’ professional quality of life such as burnout and compassion satisfaction warrant additional studies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AGFI:

-

Adjust Goodness of Fit Index

- CFI:

-

Comparitive Fit Index

- CR:

-

Critical ratio

- GFI:

-

Goodness of Fit Index

- ICC:

-

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

- IFI:

-

Incremental Fit Index

- ProQOL:

-

Professional Quality of Life Scale

- RMSEA:

-

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- TLI:

-

Tucker-Lewis Index

References

Southwick SM, Charney DS. Resilience: The science of mastering life's greatest challenges. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2018.

American Psychology Association Help Center. Accessed Oct 19, 2019 at https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx

Cyrulnik B. Resilience. London: Penguin; 2009.

Burgis-Kasthala S, Elmitt N, Smyth L, Moore M. Predicting future performance in medical students. A longitudinal study examining the effects of resilience on low and higher performing students. Med Teach. 2019;41(10):1184–91.

Aboalshamat KT, Alsiyud AO, Al-Sayed RA, Alreddadi RS, Faqiehi SS, Almehmadi SA. The relationship between resilience, happiness, and life satisfaction in dental and medical students in Jeddah. Saudi Arabia Niger J Clin Pract. 2018;21(8):1038–43.

Shi M, Wang X, Bian Y, Wang L. The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between stress and life satisfaction among Chinese medical students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:16.

Kim NE, Cho SM. Quality of life of medical students during clinical clerkship. Korean J Med Educ. 2012;24(4):353–7.

Shi M, Liu L, Wang ZY, Wang L. The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between big five personality and anxiety among Chinese medical students: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119916.

Helou MA, Keiser V, Feldman M, Santen S, Cyrus JW, Ryan MS. Student well-being and the learning environment. Clin Teach. 2019;16(4):362–6.

Zhao F, Guo Y, Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H. Subjective well-being and its association with peer caring and resilience among nursing vs medical students: a questionnaire study. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;37:108–13.

Rahimi B, Baetz M, Bowen R, Balbuena L. Resilience, stress, and coping among Canadian medical students. Can Med Educ J. 2014;5(1):e5–e12.

Kiziela A, Viliūnienė R, Friborg O, Navickas A. Distress and resilience associated with workload of medical students. J Ment Health. 2019;28(3):319–23.

Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier C. A conceptual model of medical student well-being: promoting resilience and preventing burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):44–53.

Houpy JC, Lee WW, Woodruff JN, Pincavage AT. Medical student resilience and stressful clinical events during clinical training. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1320187.

Lin CD, Lin BY. Training demands on clerk burnout: determining whether achievement goal motivation orientations matter. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):214.

Alsaggaf MA, Wali SO, Merdad RA, Merdad LA. Sleep quantity, quality, and insomnia symptoms of medical students during clinical years. Relationship with stress and academic performance. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(2):173–82.

Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132–49.

Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1987.

Wagnild GM. The resilience scale User’s guide for the US English version of the resilience scale and the 14-item resilience scale (RS-14). The Resilience Center: Montana; 2009.

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate Data Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Macmillan; 1987. p. 149.

Yung YF, Bentler PM. Bootstrapping techniques in analysis of mean and covariance structures. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: issues and techniques. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1996. p. 195–226.

Al-Nasir FA, Robertson AS. Can selection assessments predict students' achievements in the premedical year? A study at Arabian Gulf University. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2001;14(2):277–86.

Karasek RA, Gordon G, Pietrokovsky C, Frese M, Pieper C, Schwartz J, Fry L, Schirer D. Job Content Instrument: Questionnaire and User‘s Guide. Los Angeles: University of Southern California; 1985.

Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The job content questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(4):322–55.

Stamm BH. Professional Quality of Life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue version 5 (ProQOL). 2009. Available: http://www.isu.edu/~bhatamm or www.proqol.org. Accessed Aug 01 2017.

Elizondo-Omaña RE, García-Rodríguez Mde L, Hinojosa-Amaya JM, Villarreal-Silva EE, Avilan RI, Cruz JJ, Guzmán-López S. Resilience does not predict academic performance in gross anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3(4):168–73.

Stamm BH. The Concise ProQOL Manual, 2nd Ed. Pocatello, ID: ProQOL.org. 2010

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence; 1988.

Bliese P. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability. In: Klein K, Kozlowski S, editors. Multi-level theory, research, and methods in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000. p. 349–81.

García-Sierra R, Fernández-Castro J, Martínez-Zaragoza F. Relationship between job demand and burnout in nurses: does it depend on work engagement? J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(6):780–8.

Yin Z, Davis CL, Moore JB, Treiber FA. Physical activity buffers the effects of chronic stress on adiposity in youth. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29(1):29–36.

van Dijk I, Lucassen PLBJ, van Weel C, Speckens AEM. A cross-sectional examination of psychological distress, positive mental health and their predictors in medical students in their clinical clerkships. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):219.

Poncelet A, O'Brien B. Preparing medical students for clerkships: a descriptive analysis of transition courses. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):444–51.

Haglund ME. aan het rot M, Cooper NS, Nestadt PS, Muller D, Southwick SM, Charney DS. Resilience in the third year of medical school: a prospective study of the associations between stressful events occurring during clinical rotations and student well-being. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):258–68.

Greenhill J, Fielke KR, Richards JN, Walker LJ, Walters LK. Towards an understanding of medical student resilience in longitudinal integrated clerkships. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:137.

Kilminster SM, Jolly BC. Effective supervision in clinical practice settings: a literature review. Med Educ. 2000;34(10):827–40.

Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen HA, Essed GG, Scherpbier AJ, Van Der Vleuten CP. Students' perceptions of relationships between some educational variables in the out-patient setting. Med Educ. 2002;36(8):735–41.

Ruitenburg MM, Frings-Dresen MH, Sluiter JK. Physical job demands and related health complaints among surgeons. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(3):271–9.

Thielen K, Nygaard E, Andersen I, Diderichsen F. Employment consequences of depressive symptoms and work demands individually and combined. Eur J Pub Health. 2014;24(1):34–9.

Raman M, Donnon T. (2008). Procedural skills education--colonoscopy as a model. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(9):767–70.

Kovatz S, Kutz I, Rubin G, Dekel R, Shenkman L. Comparing the distress of American and Israeli medical students studying in Israel during a period of terror. Med Educ. 2006;40(4):389–93.

Mueller G, Hunt B, Wall V, Rush R Jr, Molof A, Schoeff J, Wedmore I, Schmid J, Laporta A. Intensive skills week for military medical students increases technical proficiency, confidence, and skills to minimize negative stress. J Spec Oper Med. 2012;12(4):45–53.

McLeod PJ, Steinert Y, Trudel J, Gottesman R. Seven principles for teaching procedural and technical skills. Acad Med. 2001;76(10):1080.

Delany C, Miller KJ, El-Ansary D, Remedios L, Hosseini A, McLeod S. Replacing stressful challenges with positive coping strategies: a resilience program for clinical placement learning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(5):1303–24.

Galante J, Dufour G, Benton A, Howarth E, Vainre M, Croudace TJ, Wagner AP, Stochl J, Jones PB. Protocol for the mindful student study: a randomised controlled trial of the provision of a mindfulness intervention to support university students' well-being and resilience to stress. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012300.

Lukey BJ, Tepe V. Biobehavioral resilience to stress. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2008.

Maddi SR. The story of hardiness: twenty years of theorizing, research, and practice. Consult Psychol J. 2002;54:173–85.

Maddi SR, Brow M, Khoshaba DM, Vaitkus M. The relationship of hardiness and religiosity in depression and anger. Consult Psychol J. 2006;58(3):148–61.

Howe A, Smajdor A, Stöckl A. Towards an understanding of resilience and its relevance to medical training. Med Educ. 2012;46(4):349–56.

Uji M, Kitamura T, Nagata T. Self-conscious affects: their adaptive functions and relationship to depressive mood. Am J Psychother. 2011;65(1):27–46.

Kumar K, Greenhill J. Factors shaping how clinical educators use their educational knowledge and skills in the clinical workplace: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:68.

Farquhar J, Kamei R, Vidyarthi A. Strategies for enhancing medical student resilience: student and faculty member perspectives. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:1–6.

Kaye-Kauderer HP, Levine J, Takeguchi Y, Machida M, Sekine H, Taku K, Yanagisawa R, Katz C. Post-traumatic growth and resilience among medical students after the march 2011 disaster in Fukushima. Japan Psychiatr Q. 2019;90(3):507–18.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Funding

Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology provide the funds for this study’s academic and administrative processes and publication (MOST 106–2511-S-039 -002 -MY2 & MOST 108–2410-H-182 -011 -SS3). The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All of the authors contributed to the study design and to the analysis and interpretation of the data. BYJL, CDL, and DYC acquired the data, YKL drafted the manuscript, and all authors made substantial contributions to the manuscript. All authors reviewed, commented on, and approved publication of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital (CRREC-106-067 & CRREC-106-067 (AR-1)). All participants provided written statements of consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Blossom Yen-Ju Lin, is a member of the editorial board (Associate Editor) of BMC Medical Education. All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y.K., Lin, CD., Lin, B.YJ. et al. Medical students’ resilience: a protective role on stress and quality of life in clerkship. BMC Med Educ 19, 473 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1912-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1912-4