Abstract

Background

To evaluate personal and institutional factors related to depression and anxiety prevalence of students from 22 Brazilian medical schools.

Methods

The authors performed a multicenter study (August 2011 to August 2012), examining personal factors (age, sex, housing, tuition scholarship) and institutional factors (year of the medical training, school legal status, location and support service) in association with scores of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).

Results

Of 1,650 randomly selected students, 1,350 (81.8 %) completed the study. The depressive symptoms prevalence was 41 % (BDI > 9), state-anxiety 81.7 % and trait-anxiety in 85.6 % (STAI > 33). There was a positive relationship between levels of state (r = 0,591, p < 0.001) and trait (r = 0,718, p < 0.001) anxiety and depression scores. All three symptoms were positively associated with female sex and students from medical schools located in capital cities of both sexes. Tuition scholarship students had higher state-anxiety but not trait-anxiety or depression scores. Medical students with higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms disagree more than their peers with the statements “I have adequate access to psychological support” and “There is a good support system for students who get stressed”.

Conclusions

The factors associated with the increase of medical students’ depression and anxiety symptoms were female sex, school location and tuition scholarship. It is interesting that tuition scholarship students showed state-anxiety, but not depression and trait-anxiety symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global prevalence of depression among medical students was recently estimated to be 28.0 % according to a meta-analysis of 77 studies [1]. A high prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical students has been reported worldwide [2–19]. An increased prevalence compared with age-matched peers in general population [20, 21] and with non-medical students has been reported in the literature [22].

A number of personal and institutional factors may contribute to the worsening of medical students’ mental health. Recent research discussed that medical schools provide a toxic psychological environment [23–25] where academic pressure, workload, financial hardships, sleep deprivation are stressors factors [2, 26]. Depression and anxiety symptoms carry impairment to medical students, including poorer in academic performance, drop out, substance abuse and suicide [14, 15, 26, 27]. Moreover poor mental health is a predictor of later distress in the physician [27, 28].

While there is a growing literature on prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms and about potential causal factors to the high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among medical students, few studies have had a large enough sample and focused on prevalence rates related to both depression and anxiety symptoms in a multicenter study design [2, 3, 29].

In our study we aimed (a) to investigate the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms among medical students in 22 Brazilian medical schools; (b) to study their association with personal factors (age, sex, housing, tuition scholarship) and institutional factors (year of the medical training, school legal status (public/private), location and support service). This baseline examination is part of the VERAS Project (acronym for Life of students and residents from health professions).

Methods

Study design and sample

VERAS study is a multicenter study involving 22 Brazilian medical schools to evaluate quality of life, emotional competencies and educational environment of students and residents of health professions [30–32].

The participating schools were selected by convenience and were geographically distributed across the country, with a diverse legal status and locations (13 public and 9 private schools; 13 in state capital cities and 9 in other cities).

The sample size (n = 1,152) was initially calculated to enable an effect size of 0.165 between two groups of the same size, with 80 % power at a 0.05 significance level. Later, we increased the sample to 1,650 students to account for 30 % of loss of participants. At least 60 medical students, stratified in clusters by gender and program year (i.e., 5 males, 5 females per each of the six training years) were randomly selected using a computer-generated list of random numbers [30–32]. The participation in the study was voluntary without any financial compensation. All participants signed an informed consent form in which confidentiality were guaranteed.

Data collection

Data were collected from August 2011 to August 2012 through a survey platform. The randomly selected students received a link by e-mail to access the questionnaires and a full 10 days were provided to answer the survey. Once all questionnaires were answered each student received an individual and immediate feedback online for his/her scores. The participants had the opportunity to contact coordinator researchers for guidance and/or emotional support [30–32].

Instruments

Socio-demographic is a 14-item questionnaire to access age, sex, year of medical training, tuition scholarship and housing.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21-item questionnaire to measure depression symptoms. Each item scores vary from 0 to 3 according to increasing symptom intensity [32]. The cut-offs for the BDI scores were defined as: no depression (0 to 9), mild (10 to 17 points), moderate (18 to 29 points) and severe (30 to 63 points) [33, 34]. This questionnaire was translated to Brazilian Portuguese and demonstrates adequate reliability and validity [33]. The BDI had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 in our study.

State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a two-component scale with 20 items each evaluating the intensity of state-anxiety and frequency of trait-anxiety [35]. State-anxiety refers to a transitory emotional state which intensity may vary according to the context and over-time. It is characterized by unpleasant feelings of tension or apprehension and increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system as tachycardia, sweating and increased blood pressure. This scale assesses how the person is feeling at a specific time, the higher the score the greater feeling of apprehension, tension, nervousness and annoyance. Trait-anxiety refers to individual tendency to react to perceived situations as threatening with anxiety [36].

Anxiety symptoms according to STAI scores were defined as: low (<33), medium (33–49) and high (> 49) [16]. The Brazilian Portuguese version of this inventory demonstrates adequate reliability and validity [34, 37]. In the present study the STAI had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0,93 for trait-anxiety and 0,92 for the state-anxiety scales.

Study variables

We analyzed sex, age, years of the medical training, school legal status (public or private), and school location (state capital or other cities), tuition scholarship, housing (alone or with someone), support service, BDI and STAI scores. In Brazil, the Medical degree is obtained in a 6 years undergraduate program and it is generally stratified into three periods: basic sciences (1st and 2nd years), clinical sciences (3rd and 4th years) and clerkship (5th and 6th years). We respected this classification in our study.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as proportions and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation. Chi-squared and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used whenever applicable. We built multinomial logistic regression models to study whether age, sex, housing accommodations, year of medical training, school legal status (public or private), school location (state capital or other cities), and tuition scholarship were associated with depressive symptoms, state-anxiety or trait-anxiety. All models included age, sex and year of medical training as independent variables; so all results are adjusted for these characteristics. Assessing multicollinearity directly from multinomial models yields results of very difficult interpretation. Therefore, we assessed multicollinearity among the independent variables in all models calculating the variance inflation factors (VIF) of correspondent linear models. In these linear models, the independent variables were the same used in the multinomial models. In all cases, VIF values were below 1.4, showing there was no substantial multicollinearity among the independent variables. Statistical analysis was performed on R software version 3.1.1 (Vienna, Austria). Significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

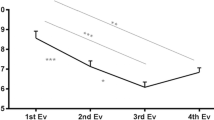

In this sample of 1,350 medical students (response rate 81.8 %) [30–32]. 557 (41.3 %) individuals had a BDI score of 10 points or higher, indicating the presence of mild depressive symptoms, at least. Additionally, 1,103 (81.7 %) and 1,155 (85.6 %) students had STAI scores above the threshold for moderate state and trait anxiety symptoms, respectively. Sample distributions of BDI and STAI scores according to socio-demographic variables are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. In bivariate analyses, female students (p < 0.001) and students from schools located in capital cities (p = 0.001) referred more depressive symptoms. State anxiety symptoms were also more frequent in females (p < 0.001). Trait anxiety was more frequent in females (p < 0.001) and in students living in capital cities (p = 0.026). We did not find significant differences when years of the medical school were taken into account for depression (p = 0.859), state anxiety (p = 0.624) and trait anxiety (p = 0.4267) symptoms.

Table 3 describes the coexistence of depression and anxiety symptoms. Individuals with depression are more prone to present state and/or trait anxiety symptoms. High state anxiety scores are present in 14,4 %, 43,9 % and 73,8 % of participants with no, mild and moderate/severe depression, respectively. High trait anxiety scores are present in 15,3 %, 53,0 % and 90,1 % of participants with no, mild and moderate/severe depression respectively. A substantial number of participants have coexistence of those conditions. We found that 165 (12.2 %) individuals had simultaneously moderate to severe depressive symptoms and medium to high state anxiety symptoms, and 171 (12.7 %) individuals had moderate to severe depressive symptoms and medium to high trait anxiety symptoms.

Table 4 shows the results of multinomial logistic regression models for the association between students or schools’ characteristics and depressive, state anxiety and/or trait anxiety scores. Female sex was associated with higher depressive, state anxiety and trait anxiety scores. We also found a significant, dose-effect direct association between studying in schools in capital cities and both depressive symptoms and trait anxiety scores. In addition, we also found a significant positive association between schools in capital cities and the highest level of state anxiety symptoms. Benefits from financial aid programs offering tuition was positively associated with state anxiety, but not with trait anxiety or depressive symptoms.

Only 342 (25.3 %) participants agreed to the statement “I have adequate access to psychological care” (statement 1) while 153 (11.3 %) participants agreed with the statement “There is a good support system for students who get stressed” (statement 2) (Table 5). It is noteworthy these concordance rates were even lower in individuals with more anxiety and depressive symptoms. We observed a significant trend for lower concordance with the statement 1 in individuals with more prominent state (p for trend < 0.001) and trait (p for trend = 0.019) anxiety symptoms. A similar, but non-significant trend (p for trend = 0.056) was also observed for the association with increasingly depressive symptoms. For the statement 2 there was a statistically significant trend for lower concordance rates in individuals with more intense depressive (p for trend = 0.033), state anxiety (p for trend = 0.003) and trait-anxiety (p for trend = 0.020) symptoms.

Discussion

We found a high prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among Brazilian medical students. A substantial number of students had coexistent anxiety and depressive symptoms. Females, tuition scholarship students and students from medical schools located in capital cities were more prone to have anxiety and/or depressive symptoms. According to students’ perceptions, the access to psychological care and support is not sufficient.

The prevalence of depressive symptoms in Brazilian medical students (41.3 %) is higher than the global prevalence (28.0 %) recently estimated by a meta-analysis of 62 728 medical students and 1,845 non-medical students pooled across 77 studies (95 % confidence interval [CI] 24.2–32.1 %) [1]. Our findings of a high prevalence of state-anxiety (81.7 %) and trait-anxiety (85.6 %) in medical students are consistent with previous studies [21, 38, 39]. There are evidences that depression and mean trait-anxiety scores in medical students are even higher when compared to age-matched controls in the general population [20, 21]. However, the high trait-anxiety prevalence found in present study is similar to that reported in Brazilian age-matched undergraduate students [37, 40]. High depression prevalence was reported among students of humanities, exact sciences [41] and health services [42]. According to the literature it continuous unclear if depression and anxiety symptoms is more common in medical students than non-medical [22, 38].

We found a high coexistence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among medical students. In the 1980s some researchers questioned if anxiety and depression could be reliably differentiated using STAI and BDI [43, 44]. Currently there are consistent evidences of the adequate psychometrics properties of both BDI and STAI scales [34, 45, 46]. These results are consistent to the epidemiological studies that shown major depressive disorder has high comorbidity with numerous anxiety disorders in general population [20, 21].

Our data showed that female medical students were more prone to have depressive and anxiety symptoms than males. Comparisons of depressive and anxiety symptoms by gender among medical students yielded mixed findings showing either no difference or high prevalence among female medical students [1–3]. The higher prevalence of depression in female medical students has multiple explanations, including cultural aspects related to social stigma and gender inequity [39, 47], personality traits [7, 48], conflicting role demands [48], and medical educational environment [23–25, 47, 50]. An important factor to be considered is the medical education practices. Evidences shown that the educational environment has a significant impact on the well being of medical students [50]. A recently study showed that female medical students feel more discouraged and tired in medical training than the male colleagues and also reported greater solitude and a more negative perception of their social life [32]. The adaptation in medical schools that are no longer exclusively masculine with education practices that support a dominant patriarchy culture, seems to have a high psychological cost for women [47–51]. In Brazilian the proportion of females in medical schools increased in recent years from 46.3 % of 47 386 applicants in 1995 to 55.6 % in 2011 [52]. Although women are worldwide majority in medical schools and medical workforce there is inequity of opportunities in academic and across the professional [53].

In our study tuition scholarship students showed state-anxiety, but not trait-anxiety or depressive symptoms. Hojat et al. reported that among first- and second-year students at the Jefferson Medical College, 42 % had experienced financial problems in the previous 12 months and considered it as a stressful life event [48]. Wege et al. 2016 reported the association between financial hardships with poor mental health and psychosomatic symptoms [4].

Entering in medical undergraduation required to the students changing their lifestyles [25, 54]. One of these changes is living faraway from families and friends outside their hometowns. In this case housing accommodations (alone or with peers) can impact the students’ well-being and quality of life during the medical training [25]. Our hypothesis that students who live alone have higher depression and anxiety scores was not confirmed. Furthermore we confirmed the hypotheses that students from medical schools located in capital cities showed higher depression and anxiety scores. This suggests some factors related to the lifestyle more common in capital cities, like traffic, violence, may play a role in student mental health [55].

Related to institutional factors associated with anxiety and depression prevalence, we found no significant difference among years of the medical school, in contrast to previous studies [2, 25, 40]. Vitalino et al. reported that the number of depressed and anxiety students increased at the end of the first semester [40]. In the otherwise Ball and Bax noted BDI scores peaked in mid semester and returned to baseline by the end of the semester [54]. Longitudinal studies which compared the 4 years of American medical school reported that the depression scores peaked in the end of the second year but remained higher than baseline among fourth-year students [56, 57]. Differences in study populations may be responsible for these conflicting findings. On the other hand, those studies had convenience samples, and we could speculate that volunteer students may be those facing greater suffering along the medical training or have a more critical view when compared to randomly sampled students.

Another institutional factor was the access to psychological support, students with more depression and anxiety symptoms disagree more than their peers with the statements “I have adequate access to psychological support” and “There is a good program to stress in my school”. Hillis et al. reported that most of the students (71 %) knew about support services available in their schools, although few of them reported that services were properly offered [58]. This could suggest that medical students with more depression and anxiety symptoms either have less access to a psychological support or/and perceive it as adequate.

The strengths of this study are that it is consisted of a large, multicenter, randomly selected sample, from Brazilian schools located in all regions of the country and with a high response rate. We used validated questionnaires to address anxiety and depression symptoms. Our results must be interpreted in their context also. Our study has a cross-sectional design, which does not allow inferences of causality. Our sample was restricted to Brazilian medical students, and differences in study populations require caution to extend its findings to other settings.

Our findings offer evidences to drive interventions to deal with personal and institutional factors that affect medical students’ mental health, especially among females and students with financial hardships. These evidences suggest that medical schools should development programs to promote gender and social equity and strategies to improve psychological support services.

The comprehension of anxiety and depression in medical undergraduation context can be a step to improve educational environment, change habits and help the development of the new generation of physicians. There is growing literature on the health and well-being, yet few studies about medical students’ anxiety. A meta-analysis on anxiety among medical students would contribute with a global overview, along to longitudinal studies to establish causality.

Conclusions

We found a high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in VERAS study participants. The factors associated with the increase of medical students’ depression and/or anxiety symptoms were female sex, school location and financial problems. Regarding to the years of the medical school we found no significant difference. According to students’ perceptions, the access to psychological care and support is not sufficient.

Abbreviations

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- STAI:

-

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

- VERAS:

-

Vida do estudante e residente da área da saúde (Life os Students and Residents from Health Professions)

References

Puthran R, Zhang MW, Tam WW, Ho RC. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: a meta-analysis. Med Educ. 2016;50(4):456–68. doi:10.1111/medu.12962. Review.

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81:354–73.

Hope V, Henderson M. Medical student depression, anxiety and distress outside North America: A systematic review. Med Educ. 2014;48:963–79.

Wege N, Muth T, Li J, Angerer P. Mental health among currently enrolled medical students in Germany. Pub Health. 2016;132:92–100.

Abdel Wahed WY, Hassan SK. Prevalence and associated factors of stress, anxiety and depression among medical Fayoum University students. Alex J Med. 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajme.2016.01.005.

Venrooij LT, Barnhoorn P, Giltay E, Noorden MS. Burnout, depression and anxiety in preclinical medical students: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;aop.

Shi M, Liu L, Wang YZ, Wang L. The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between big five personality and anxiety among Chinese medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119916.

Seweryn M, Tyrala K, Kolarezy-Haczyk A, Bonk M, Bulska W. Krysta k. Evaluation of the level of depression among medical students from Poland, Portugal and Germany. Psych Dan. 2015;27(1):216–22.

Bassols, et al. First- and Last-year medical students: is there a difference in the prevalence and intensity of anxiety and depressive symptoms? Rev Bras Psic. 2014;36:233–40.

Burger PH, Tektas O, Paulsen F, Stolz M. From Freschmanship to the first “Staatsexamen” – Increase of Depression and Decline in Sense of Coherence and Mental Quality of Life in Advanced medical Students. Psychother Psych Med. 2014;64:322–7.

Yusoff, et al. The impact of medical education on psychological health of students: A cohort study. Psych, Health & Med. 2013;18(4):420–30.

Kulsoom B, Afsar NA. Stress, anxiety, and depression among medical students in a multiethnic setting. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;16(1):1713e22.

Borst JM, Frings-Dresen MH, Sluiter JK. Prevalence and incidence of mental health problems among Dutch medical students and the study-related and personal risk factors: a longitudinal study. Int J Adolesc Med Health; 2015. ISSN (Online) 2191-0278, ISSN (Print) 0334-0139. doi:10.1515/ijamh-2015-0021.

Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Gronvold NT, Ekeberg O. Suicidal ideation among medical students and young physicians: a nationwide and prospective study of prevalence and predictors. J Affect Disord. 2001;64(1):69e79.

Midtgaard M, Ekeberg O, Vaglum P, Tyssen R. Mental health treatment needs for medical students: a national longitudinal study. J Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(7):505e11.

Konjengbam S, Laishram J, Singh BA, Elangbam V. Psychological morbidity among undergraduate medical students. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59(1):65e6.

Sobowale K, Zhou N, Fan J, Liu N, Sherer R. Depression and suicidal ideation in medical students in China: a call for wellness curricula. Int J Med Educ. 2014;15(5):31e6.

Tan ST, Sherina MS, Rampal L, Normala I. Prevalence and predictors of suicidality among medical students in a public university. Med J Malays. 2015;70(1):1e5.

Osama M, Islam MY, Hussain SA, Masroor SM, Burney MU, Masood MA, et al. Suicidal ideation among medical students of Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. J Forensic Leg Med. 2014;27:65e8.

Dahlin ME, Runeson B. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among medical students entering clinical training: a three year prospective questionnaire and interview-based study. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:6.

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–51.

Bacchi S, Licinio J. Qualitative literature review of the prevalence of depression in medical students compared to students in non-medical degrees. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39:293–9.

Wolf TM. Stress, coping and health: enhancing well-being during medical school. Med Educ. 1994;28:8–17.

Finkelstein C, Brownstein A, Scott C, Lan Y. Anxiety and stress reduction in medical education: an intervention. Med Educ. 2007;41:258–64.

Tempski P, Bellodi PL, Paro HB, Enns SC, Martins MA, Schraiber LB. What do medical students think about their quality of life? A qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:1.

Stewart SM, Lam TH, Betson CL, Wong CM, Wong AM. A prospective analysis of stress and academic performance in the first two years of medical school. Med Educ. 1999;33:243–50.

Walkiewicz M, Trtas M, Majkowicz M, Budzinski W. Academic achievement, depression and anxiety during medcial education predict the styles of success in a medical carrer: a 10-year longitudinal study. Med Teach. 2012;34(9):e611–9.

Stoen Grotmol K, Gude T, Moum T, Vaglum P, Tyssen R. Risk factors at medical school for later severe depression: a 15-year longitudinal, Nationwide study (NORDOC). J Affect Disord. 2012;146(1):106–11.

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huschka MM, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, et al. A multicenter study of burnout, depression, and quality of life in minority and nonminority US medical students. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(11):1435–42.

Paro HBMS, Silveira PSP, Perotta BG, Enns SC, Giaxa R, Bonito R, et al. Empathy among medical students: Is there a relation with quality of life and burnout? PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94133.

Tempski P, Santos IS, Mayer FB, Enns SC, Perotta B, Paro HBMS, et al. Relationship among medical students resilience, educational environment and quality of life. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131535.

Enns SC, Perotta B, Paro HB, Gannam S, Peleias M, Mayer FB, et al. Medical students perception of their educational environment and quality of life - Is there a positive association? Acad Med. 2015;91(3):409–17.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71.

Gorenstein C, Andrade L. Validation of a Portuguese version of the Beck Depression Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory in Brazilian subjects. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1996;29(4):453–7.

Biaggio AMB, Natalicio L, Spielberger CD. Desenvolvimento da forma experimental em português do inventário de Ansiedade Traço-Estado (IDATE) de Spielberger. Arq Bras Psic apl. 1977;29(3):31–44.

Spielberger G. Lushene. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting psychologists Press; 1983.

Andrade L, Gorenstein C, Vieira Filho AH, Tung TC, Artes R. Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory applied to college students: factor analysis and relation to the Beck Depression Inventory. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:367–74.

Aktekin M, Karaman T, Senol YY, Erdem S, Erengin H, Akaydin M. Anxiety, depression and stressful life events among medical students: a prospective study in Antalya, Turkey. Med Educ. 2001;35:12–7.

Hardeman RR, Przedworski JM, Burke SE, Burgess DJ, Phelen SM, Dovidio JF, Nelson D. Mental well-being in first year medical students: A comparison by race and gender. J Racial Ethn Disparities. 2015;2(3):403–13.

Vitaliano PP, Maiuro RD, Russo J, Mitchell ES. Medical student distress. A longitudinal study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(2):70–6.

Lupo MK, Strous RD. Reliosity, anxiety and depression among Israeli medical students. Isr Med Educ. 2011;11:92.

Kaya M, Genç M, Kaya B, Pehlivan E. Prevalence of depressive symptoms, ways of coping, and related factors among medical school and health services higher education students. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2007;18(2):132–46.

Tanaka-Matsumi J, Kameoka VA. Reliabilities and concurrent validities of popular self-report measures of depression, anxiety, and social desirability. J Consul Clin Psych. 1986;54(3):328–33.

Gotlieb IH. Depression and general psychopathology in university students. J Abn Psych. 1984;93(1):19–30.

Endler NS, Cox BJ, Parker JD, Bagby RM. Self-reports of depression and state-trait anxiety: evidence for differential assessment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63(5):832–8.

Ortuño-Sierra J, Garcia-Velasco L, Inchausti F, Debbané M, Fonseca-Pedrero E. New approaches on the study of the psychometric properties of the STAI. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2016;44(3):83–92.

Bleakley A. Gender matters in medical education. Med Educ. 2013;47:59–70.

Hojat MGK, Xu GVJJ, Christian EB. Gender comparisons of medical students’ psychosocial profiles. Med Educ. 1999;33:342–9.

Peleg-Sagy T, Shahar G. Depression and sexual satisfaction among female medical students:Suprising findings from a pilot study. Psychiatry. 2012;75:2.

Genn JM. AMEE Medical Education Guide No.23 (Part 2): Curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education–a unifying perspective. Med Teach. 2001;23(5):445–54.

Verlander G. Feale physicians:Balancing carrer and family. Acad Psych. 2004;28(4):331–6.

Medical students and physicians in Brazil: current numbers and projections. http://www2.fm.usp.br/cedem/docs/relatorio1_final.pdf.

McKinstry B. Are there too many female medical graduates? BMJ. 2008;336:748.

Ball S, Bax A. Self-care in medical education: effectiveness of health-habits interventions for first-year medical students. Acad Med. 2002;77(9):911–7.

WHO-World Health Organisation. The World health report 2002: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. 2002.

Clark DC, Zeldow PB. Vicissitudes of depressed mood during four years of medical school. JAMA. 1988;260(17):2521–8.

Rosal MC, Ockene IS, Ockene JK, Barrett SV, Ma Y, Hebert JR. A longitudinal study of students’ depression at one medical school. Acad Med. 1997;72(6):542–6.

Hillis JM, Perry WR, Carroll EY, Hibble BA, Davies MJ, Yousef J. Painting the picture Australasian medical student views on wellbeing teaching. Med J Aust. 2010;192(4):188–90.

Acknowlegments

The authors would like to thank the following associate researchers - all members of the VERAS Collaborative Research Group - for their hard work recruiting students: Ana Carolina Faedrich dos Santos (Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre (UFCSPA), Bruno Perotta (Faculdade Evangélica do Paraná), Cláudia Vasconcelos (FMP), Cleane Toscano S. Bezerra (Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Paraíba (FCMPB), Cristiane Barelli (Universidade de Passo Fundo), Derly Streit (Faculdade de Medicina de Petrópolis (FMP), Emilia Perez (FCMPB), Emirene M T Navarro da Cruz (Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto), Helena Borges Paro (Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (UFU)), Ivan Antonello (Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul), Katia Burle dos Santos Guimarães (Faculdade de Medicina de Marília), Luís Fernando Tófoli (Universidade Federal do Ceará), Maria Amélia Dias Pereira (Universidade Federal de Goiás), Maria Helena Senger (Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Sorocaba), Maria Luísa Carvalho Soliani (Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública (EBMSP), Marta Menezes (EBMSP), Munique Peleias (Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (FMUSP)), Nilson Rodrigues da Silva (Faculdade de Medicina do ABC (FMABC)), Olívia Maria Veloso Costa Coutinho (UFT), Renata RB Giaxa (Universidade de Fortaleza), Rosuita F Bonito (UFU), Sergio Baldassin (FMABC), Sylvia Claassen Enns (FMUSP), Vera Lucia Garcia (Universidade Estadual de São Paulo).

Funding

This study was supported by CAPES (Brazilian Federal Agency for the Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education) and CNPq (National Council for Scientific Development), Brazil. CAPES supported the development of the survey platform and data collection. CAPES and CNPq funded scholarships for graduate students.

Availability of data and material

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Author’s contributions

FBM and ISS participated in the analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. PSPS participated in the conception and design of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript. MHIL, ARNDS, EPC, BALA, IH, CRM, MCPL, RA and MS carried out the data collection and critically reviewed the manuscript. PT participated in the conception and design of the study, in the analysis and interpretation of data and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have non-financial competing interests concerning the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo, as well as the institutional review boards at each participating school, approved the study. All students participating in the study signed the informed consent in the survey platform.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Brenneisen Mayer, F., Souza Santos, I., Silveira, P.S.P. et al. Factors associated to depression and anxiety in medical students: a multicenter study. BMC Med Educ 16, 282 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0791-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0791-1