Abstract

Background

Chlamydia infection in acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is associated with serious complications including ectopic pregnancy, tubal infertility, Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome and tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA). This study compared clinical and laboratory data between PID with and without chlamydia infection.

Methods

The medical records of 497 women who were admitted with PID between 2002 and 2011 were reviewed. The patients were divided into two groups (PID with and without chlamydia infection), which were compared in terms of the patients’ characteristics, clinical presentation, and laboratory findings, including inflammatory markers.

Results

The chlamydia and non-chlamydia groups comprised 175 and 322 women, respectively. The patients in the chlamydia group were younger and had a higher rate of TOA, a longer mean hospital stay, and had undergone more surgeries than the patients in the non- chlamydia group. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and CA-125 level were higher in the chlamydia group than in the non-chlamydia group, but there was no significant difference in the white blood cell count between the two groups. The CA-125 level was the strongest predictor of chlamydia infection, followed by the ESR and CRP level. The area under the receiving operating curve for CA-125, ESR, and CRP was 0.804, 0.755, and 0.663, respectively.

Conclusions

Chlamydia infection in acute PID is associated with increased level of inflammatory markers, such as CA-125, ESR and CRP, incidence of TOA, operation risk, and longer hospitalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is caused by colonization of the endocervix by microorganisms, which then ascend to the endometrium and fallopian tube. Inflammation can be at any point along a continuum that includes endometritis, salpingitis, and peritonitis [1]. PID, one of the most important infections in sexually active women of reproductive age, is a major public health problem [2].

The polymicrobial etiology of PID can be delineated artificially into sexually transmitted infections that colonize the upper genital tract, including Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and endogenous microorganisms found in the vagina, particularly anaerobic bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Haemophilus influenzae, enteric Gram-negative rods, and Streptococcus agalactiae [3, 4].

Chlamydia trachomatis is a Gram-negative bacterium that infects the columnar epithelium of the cervix, urethra, and rectum and a common bacterial cause of sexually transmitted infections [5]. Chlamydia infection is associated with a wide spectrum of upper genital tract pathologies, ranging from asymptomatic endometritis to symptomatic salpingitis, peritonitis, tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA), Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (FHCS) characterized by inflammation in perihepatic capsules, and long-term sequelae such as infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain [6–8]. Moreover, chlamydia infection can lead to obstetric complications, including premature rupture of the membrane, chorioamnionitis, premature delivery, puerperal and neonatal infections, and an increased risk of the development of cervical carcinoma [9]. Prompt treatment and screening for chlamydia infections in women of reproductive age is essential to prevent severe damage to the reproductive organs; Consequently, chlamydia screening and treatment programs have been implemented in many countries [10].

A few studies on the comparison between chlamydia and non-chlamydia infection in women with PID have been reported; however, previous studies mainly focused on the comparisons of clinical characteristics and sequelae [11–13].

This study compared the clinical course of PID with and without chlamydia infection by examining patients’ clinical and laboratory data on admission.

Methods

Participants

We reviewed the medical records of 1,422 women diagnosed with PID, salpingitis, endometritis, FHCS, or a TOA, who were treated at St. Vincent’s Hospital (Suwon, Korea) between January 2002 and December 2011 with a diagnosis at discharge of PID, salpingitis, endometritis, or TOA. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Catholic University of Korea(C11RIMI0130V).

The definition of PID was based on a clinical history of abdominal pain and on clinical findings of abdominal pain, cervical motion tenderness, and adnexal tenderness. In addition, at least one or more minor criterion was required: temperature ≥38.3°C, an abnormal cervical or vaginal mucopurulent discharge, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and laboratory documentation of a cervical infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis [14]. All patients underwent pelvic ultrasonography or abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT).

FHCS was indicated the following: (1) abdominal CT showing pelvic inflammation with contrast enhancement of hepatic capsules, or (2) adhesions between the liver and the diaphragm or the liver and the anterior abdominal wall as detected by laparoscopic surgery [15]. TOA was diagnosed based on the presence of an abscess, indicated by a tender adnexal mass or masses and ultrasonographic or abdominal CT findings supporting an abscess. The sonographic diagnosis of TOA was based on the demonstration of a complex, cystic mass with thick, irregular walls, partitions, internal echoes, and absent peristalsis [16]. The finding of TOA by CT was based on adnexal wall thickening and enhancement with complex fluid collections that may contain internal septa and a fluid-debris level [17]. The diagnosis of TOA was based on satisfying the PID criteria and the presence of at least one complex pelvic mass as mentioned above for ultrasonographic or CT findings [14].

Participants were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) no assessment of the CA-125 level (n = 378); (2) not performing vaginal swab for a chlamydia infection (n = 323); (3) not meeting the diagnostic criteria of PID (n = 167); (4) the presence of a uterine or adnexal pathology, including epithelial and germ cell ovarian neoplasms, endometriosis, leiomyoma, or adenomyosis (n = 30); (5) antibiotic use over the preceding 7 days (n = 21); and (6) obstetric delivery or abortion in the previous 30 days (n = 6). We measured the axillary body temperature of all patients, with fever defined as a temperature of ≥38°C. The white blood cell (WBC) count for each patient was quantified using the XE-2100™ automated hematology system (Sysmex Inc., Mundelein, IL, USA). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) were 1.7 and 1.9%, respectively. Leukocytosis was defined as a WBC count greater than ≥11,000/mm3. The serum ESR was measured using a modified version of the Westergren method with a Test-1 automated analyzer (Ailfax, Padova, Italy). The intra- and inter-assay CVs were 3.5 and 3.4%, respectively. The upper limit of normal for the ESR in females ≤50 years of age is 20 mm/h [18]. The serum CRP level was measured by a turbidimetric immunoassay (TIA) using a Hitachi 7600-110® automatic analyzer (Hitachi Co., Tokyo, Japan). The intra- and inter-assay CVs were 5.4 and 2.7%, respectively. Normal serum CRP levels range from 0 to 0.6 mg/dl. The serum CA-125 level was measured by a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) using a CA-125 II™ kit (Abbott Architect, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The intra- and inter-assay CVs were 2.4 and 3.9%, respectively. CA-125 was considered abnormal if the concentration was ≥35 IU/ml. Endocervical swabbing and testing by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were done to identify Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis.

The two groups were compared statistically using a two-tailed Student’s t-test and χ 2 test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the relationship between chlamydia infection in PID and inflammatory markers. Since CA-125 is influenced by age, smoking and pelvic pathology, the association between CA-125 and chlamydia infection in PID was evaluated by logistic regression analysis and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The covariates were age, parity, histories of pelvic surgery or cesarean section, use of intrauterine device (IUD), menstrual problems, alcohol consumption, smoking, and TOA. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to determine the relationship between chlamydia infection in PID and inflammatory markers. p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Among the 497 females diagnosed with acute PID, 175 (35.2%) and 322 (64.8%) were in the chlamydia and non-chlamydia groups, respectively. The patients in the chlamydia group were younger than those in the non-chlamydia group, and the patients in the chlamydia group were less likely to be married and to have had children than those in the non-chlamydia group. There were no significant differences between the groups regarding abortion, previous pelvic surgery, previous PID episodes, IUD insertion, barrier contraceptive use, incidence of menstrual problems, and alcoholic and smoking history. The patients in the chlamydia group had more symptom of right upper quadrant pain and the patients in non-chlamydia group had more symptom of lower abdominal pain (Table 1).

There were no significant differences in the mean WBC count, leukocytosis, mean temperature, and the incidence of fever between the two groups, while the ESR, CRP, and CA-125 level were higher in the chlamydia group than the in non-chlamydia group (all P < 0.001; Table 2).

Logistic regression analysis was used to identify the independent variables that affected the serum CA-125 level. Age, smoking, and TOA were independent predictors of the serum CA-125 level (P = 0.003, 0.013, and < 0.001, respectively; Table 3). After adjusting for age, smoking, and the incidence of TOA, a significant difference in CA-125 level remained between the chlamydia and non- chlamydia groups (P = 0.001; Fig. 1).

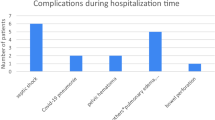

The mean length of hospital stay differed significantly; it was 8.2 ± 2.7 days for the chlamydia group and 7.2 ± 2.4 days for the non-chlamydia group (P = 0.001). In the non- chlamydia group, two cases (0.6%) were diagnosed with FHCS, versus 39.4% of the patients in the chlamydia group (P < 0.001). The incidence of surgery was higher in the chlamydia group (Table 2; 22.2 vs. 9.9%, respectively; P < 0.001). Although the rate of recurrent PID was higher in the chlamydia group, the difference between the two groups was not significant (P = 0.051). TOA was diagnosed in 13.9% of the patients hospitalized for PID (69 of 497). The incidence of TOA was higher in the chlamydia group than in the non-chlamydia group (Table 2; 25.7 vs. 7.4%, respectively; P < 0.001). In the non-chlamydia group, the occurrence of TOA was associated with IUD insertion, except in one case.

A ROC curve was constructed and used to select cut-off values as predictors of chlamydia infection. The strongest predictor of chlamydia infection was CA-125, followed by ESR and CRP. The area under the receiving operating curve (AUC) for CA-125, ESR, and CRP was 0.804, 0.755 and 0.663, respectively (Fig. 2). The cut-off values for ESR, CRP, and CA-125 are shown in Table 4; a cut-off value for the leukocyte count was not determined.

Discussion

Chlamydia infection in the lower genital tract is common in reproductive-age women, affecting mainly women younger than 25 years and 20–30% of PID cases have been attributed to Chlamydia trachomatis [2]. Studies have proved that chlamydia infection is associated with an increased risk of PID and longer PID hospitalization [19, 20]. Two-thirds of all cases of tubal factor infertility and one-third of all cases of ectopic pregnancy might be due to chlamydia infection [21].

The mechanism of PID in chlamydia infection is not yet known. Chlamydial heat shock protein 60 expression induced by the cell-mediated immune response drives inflammatory responses associated with severe sequelae of the female reproductive system [22]. A study using nonhuman primate models of lower genital tract chlamydia infection showed chronic salpingitis with extensive tubal scarring, distal tubal obstruction, and peritubal adhesions caused by an ascending infection due to cervical inoculation with chlamydia [23].

TOA is one of the most severe complications of PID and can lead to significant morbidity and occasionally mortality. TOA is caused by an infection ascending to the fallopian tube involving aerobes and anaerobes, and tubal blockage due to tubular endothelial damage and infundibular edema, ovarian invasion by organism through the site of ovulation, and adhesion formation between the ovary and fallopian tube resulting in the development of necrosis inside this complex mass, anaerobic growth, and abscess cavities [24]. An animal study showed that chlamydia infection in the lower genital tract facilitates the formation of abscesses by aerobic and anaerobic bacteria synergistically [25]. We showed that chlamydia infection was associated with a higher prevalence of TOA and an increased risk of surgery in our study.

The diagnosis of PID is based on clinical criteria. However, given the nonspecific nature of the clinical diagnosis, several diagnostic tools, including laboratory tests (e.g., WBC count, ESR, CRP level, and CA-125 level), as well as imaging, endometrial biopsy, and laparoscopy, have been introduced.

CA-125 is a glycoprotein found in the blood that is commonly used as a tumor marker of neoplasia because it can indicate ovarian cancer. CA-125 has been demonstrated in the peritoneum and epithelial tissues of Müllerian origin in the female genital tract, such as the endometrium and fallopian tube [26, 27]. Peritoneal irritation such as endometriosis, salpingitis, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, and pelvic surgery often markedly elevates the level of circulating CA-125, so the serum CA-125 level has been recommended as a useful test for acute PID [28]. Several studies have found correlations between the CA-125 level and PID [29, 30]. However, no study has examined the difference in the CA-125 level in patients with PID according to the presence of a chlamydia infection. In our study, we found a significant difference in the CA-125 level between the chlamydia and non-chlamydia groups.

The increase in serum CA-125 in patients with PID and a chlamydia infection can be explained in several ways. First, increased CA-125 levels in endometriosis might be associated with peritoneal leakage of an endometriotic cyst and an inflammatory reaction in the mesothelial cells of the peritoneum [31]. We believe that chlamydia infections cause more peritoneal irritation than other genital pathogens. Second, CA-125 antigen is found in normal adult fallopian tube epithelium, suggesting that severe inflammation of the fallopian tube can increase the serum CA-125 concentration and it is a useful marker for the clinical diagnosis of salpingitis [29]. It is possible that a pelvic chlamydia infection causes more severe inflammation of the fallopian tube than other pelvic infections. Third, TOA is a major complication of acute PID that is associated with increased serum CA-125 levels in the range of neoplastic activity [32].

To our knowledge, our study is among the first to compare clinical and inflammatory parameters between chlamydia and non-chlamydia infection in acute PID. However, our study had several limitations. First, as a retrospective study, many participants were excluded from our study because all patients with PID are not routinely examined for both CA-125 and vaginal swab for chlamydia. This might lead to selection bias. Second, the diagnosis of PID in our study was based on the medical history, clinical findings, and elevation of inflammatory markers using the CDC criteria. We did not perform a laparoscopy or endometrial biopsy to confirm PID and we failed to confirm the chlamydia infection in the pelvic organs. Although the clinical symptoms of PID in combination with one or two inflammatory parameters can increase the specificity of the diagnosis of PID, laparoscopy is recommended for confirming the diagnosis or if there is no improvement within 72 h despite adequate antibiotic therapy [33].

Conclusion

In our study, we found that genital chlamydia infection in acute PID was associated with increased inflammatory markers such as CA-125 and ESR, higher incidence of TOA and operation risk, and longer hospitalization. We need to answer other questions. Do PID and TOA have different mechanisms in genital chlamydia infection? Is there a correlation between the CA-125 level and severity of PID? Can we predict TOA or other severe sequelae using the level of CA-125 or other inflammatory markers? To answer these questions, additional experimental studies are needed to determine the mechanism of pelvic inflammation and related complications caused by a genital chlamydia infection, and to elucidate the association between the changes in inflammatory markers and the severity of infection.

Abbreviations

- CMIA:

-

Chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CVs:

-

Coefficients of variation

- FHCS:

-

Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome

- IUD:

-

Intrauterine Device

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PID:

-

Pelvic inflammatory disease

- TIA:

-

Turbidimetric immunoassay

- TOA:

-

Tubo-ovarian abscess

- WBC:

-

The white blood cell

References

Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1–94.

Soper DE. Pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 Pt 1):419–28.

Jossens MO, Schachter J, Sweet RL. Risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease of differing microbial etiologies. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(6):989–97.

Soper DE, Brockwell NJ, Dalton HP, Johnson D. Observations concerning the microbial etiology of acute salpingitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170(4):1008–14. discussion 1014-1007.

Mishori R, McClaskey EL, WinklerPrins VJ. Chlamydia trachomatis infections: screening, diagnosis, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(12):1127–32.

Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Amortegui AJ, Heine RP, Landers DV, Sweet RL. Lower genital tract infection and endometritis: insight into subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(3):456–63.

Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi H, Kitade M, Kikuchi I, Sato Y, Kinoshita K. Pathological study of Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome evaluated from fallopian tube damage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2006;32(3):280–5.

Bebear C, de Barbeyrac B. Genital Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(1):4–10.

Paavonen J, Eggert-Kruse W. Chlamydia trachomatis: impact on human reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5(5):433–47.

Gottlieb SL, Xu F, Brunham RC. Screening and treating Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease: interpretation of findings from randomized controlled trials. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(2):97–102.

Judson FN, Tavelli BG. Comparison of clinical and epidemiological characteristics of pelvic inflammatory disease classified by endocervical cultures of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. Genitourin Med. 1986;62(4):230–4.

Ness RB, Soper DE, Richter HE, Randall H, Peipert JF, Nelson DB, Schubeck D, McNeeley SG, Trout W, Bass DC, et al. Chlamydia antibodies, chlamydia heat shock protein, and adverse sequelae after pelvic inflammatory disease: the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Study. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(2):129–35.

Haggerty CL, Gottlieb SL, Taylor BD, Low N, Xu F, Ness RB. Risk of sequelae after Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in women. J Infect Dis. 2010;201 Suppl 2:S134–155.

Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110.

Hong DG, Choi MH, Chong GO, Yi JH, Seong WJ, Lee YS, Park IS, Cho YL. Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome: single centre experiences. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;30(3):277–80.

Kaakaji Y, Nghiem HV, Nodell C, Winter TC. Sonography of obstetric and gynecologic emergencies: Part II, Gynecologic emergencies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(3):651–6.

Sam JW, Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA. Spectrum of CT findings in acute pyogenic pelvic inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(6):1327–34.

Caswell M, Pike LA, Bull BS, Stuart J. Effect of patient age on tests of the acute-phase response. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117(9):906–10.

Davies B, Turner K, Ward H. Risk of pelvic inflammatory disease after Chlamydia infection in a prospective cohort of sex workers. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(3):230–4.

Reekie J, Donovan B, Guy R, Hocking JS, Jorm L, Kaldor JM, Mak DB, Preen D, Pearson S, Roberts CL, et al. Hospitalisations for pelvic inflammatory disease temporally related to a diagnosis of Chlamydia or gonorrhoea: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94361.

Scholes D, Satterwhite CL, Yu O, Fine D, Weinstock H, Berman S. Long-term trends in Chlamydia trachomatis infections and related outcomes in a U.S. managed care population. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(2):81–8.

Cohen CR, Brunham RC. Pathogenesis of Chlamydia induced pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75(1):21–4.

Bell JD, Bergin IL, Schmidt K, Zochowski MK, Aronoff DM, Patton DL. Nonhuman primate models used to study pelvic inflammatory disease caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:675360.

Chappell CA, Wiesenfeld HC. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of severe pelvic inflammatory disease and tuboovarian abscess. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(4):893–903.

Cox SM, Faro S, Dodson MG, Phillips LE, Aamodt L, Riddle G. Role of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis in intraabdominal abscess formation in the rat. J Reprod Med. 1991;36(3):202–5.

Neunteufel W, Breitenecker G. Tissue expression of CA 125 in benign and malignant lesions of ovary and fallopian tube: a comparison with CA 19-9 and CEA. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;32(3):297–302.

Zeimet AG, Offner FA, Muller-Holzner E, Widschwendter M, Abendstein B, Fuith LC, Daxenbichler G, Marth C. Peritoneum and tissues of the female reproductive tract as physiological sources of CA-125. Tumour Biol. 1998;19(4):275–82.

Mozas J, Castilla JA, Jimena P, Gil T, Acebal M, Herruzo AJ. Serum CA-125 in the diagnosis of acute pelvic inflammatory disease. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1994;44(1):53–7.

Moore E, Soper DE. Clinical utility of CA125 levels in predicting laparoscopically confirmed salpingitis in patients with clinically diagnosed pelvic inflammatory disease. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1998;6(4):182–5.

Paavonen J, Miettinen A, Heinonen PK, Aaran RK, Teisala K, Aine R, Punnonen R, Laine S, Kallioniemi OP, Lehtinen M. Serum CA 125 in acute pelvic inflammatory disease. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96(5):574–9.

Shiau CS, Chang MY, Chiang CH, Hsieh CC, Hsieh TT. Ovarian endometrioma associated with very high serum CA-125 levels. Chang Gung Med J. 2003;26(9):695–9.

Asher V, Hammond R, Duncan TJ. Pelvic mass associated with raised CA 125 for benign condition: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:28.

Schindlbeck C, Dziura D, Mylonas I. Diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): intra-operative findings and comparison of vaginal and intra-abdominal cultures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(6):1263–9.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

CCR conceived the idea and YMK, MJK, HMM obtained Data for the study. SWL participated in data analysis and interpretation. STP drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Catholic University of Korea (C11RIMI0130V).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, S., Lee, S., Kim, M. et al. Clinical characteristics of genital chlamydia infection in pelvic inflammatory disease. BMC Women's Health 17, 5 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-016-0356-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-016-0356-9