Abstract

Background

Family caregivers often report having unmet support needs when caring for someone with life-threatening illness. They are at risk for psychological distress, adverse physical symptoms and negatively affected quality of life. This study aims to explore associations between family caregivers’ support needs and quality of life when caring for a spouse receiving specialized palliative home care.

Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional design was used: 114 family caregivers completed the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) and the Quality of Life in Life-Threatening Illness – Family caregiver version (QOLLTI-F) and 43 of them also answered one open-ended question on thoughts about their situation. Descriptive statistics, multiple linear regression analyses, and qualitative content analysis, were used for analyses.

Results

Higher levels of unmet support needs were significantly associated with poorer quality of life. All CSNAT support domains were significantly associated with one or more quality of life domains in QOLLTI-F, with the exception of the QoL domain related to distress about the patient condition. However, family caregivers described in the open-ended question that their life was disrupted by the patient’s life-threatening illness and its consequences. Family caregivers reported most the need of more support concerning knowing what to expect in the future, which they also described as worries and concerns about what the illness would mean for them and the patient further on. Lowest QoL was reported in relation to the patient’s condition, and the family caregiver’s own physical and emotional health.

Conclusion

With a deeper understanding of the complexities of supporting family caregivers in palliative care, healthcare professionals might help to increase family caregivers’ QoL by revealing their problems and concerns. Thus, tailored support is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Palliative care aims to support the quality of life (QoL) of both patients and family caregivers [1, 2]. Family caregivers, for example, spouses, children, parents or others who have a significant relationship with a person with life-threatening illness, are essential [3, 4], as many patients are cared for at home towards the end of life [5,6,7]. Although palliative home care is provided by professionals [8], family caregivers are crucial providers of social support [9, 10] and a great deal of caregiving [10, 11] involving practical, emotional and existential support [10,11,12,13]. Many report unmet support needs and insufficient knowledge of caregiving wanting more information about the illness’ prognosis, progression and treatment and emotional support for themselves [10, 14,15,16]. Support needs can change during the illness trajectory and unmet needs may negatively affect family caregivers’ QoL [17, 18].

Many family caregivers put their own lives on hold and attend to the patient’s needs. In addition, they must cope with the patient’s impending death and an uncertain future [13]. When confronted with life-threatening illness, existential concerns are often evoked, forcing family caregivers to confront life’s fragility and their own mortality [19]. Many exhibit feelings of helplessness and lack of control that could lead to anxiety, but also physical symptoms, such as fatigue and sleep deprivation [13]. Moreover, family caregivers often have higher levels of anxiety and depression than those reported in the general population [20]. Spouses are often the primary caregiver, providing more care and support which also tends to increase with age. They often report higher levels of distress and more physical and psychological burden [21]. Caregiver burden has been found to negatively affect family caregivers’ QoL. Adequate support might contribute to easing burden and thus improve QoL [22]. QoL is often negatively affected, both during caregiving and after the patient’s death [20, 23] and seems to decrease as the patient deteriorates. Their situation is interwoven with that of the patient [24, 25] and it can take several months after the patient’s death for their QoL to return to a normative standard [23]. QoL is an essential part of palliative care [26]. However, it is not always easy for healthcare professionals to adequately support the maintenance of family caregivers’ QoL, as it is a broad concept affected by a person’s physical and psychological health, social relationships and personal beliefs [2].

Existing literature contributes with knowledge concerning the need for support among family caregivers [27] and some studies indicate that caregiving has a significant impact on family caregivers [28]. However, studies often include small samples, using different family caregiver populations and have not looked at support needs in relation to separate domain of QoL. More knowledge is needed to better understand what may be helpful during the caring phase and the relation between separate domains of support needs and overall as well as various domains of QoL. It is also of importance to identify which domains of support needs that might be of particular significance for the QoL of family caregivers. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore associations between family caregivers’ support needs and quality of life when caring for a spouse receiving specialized palliative home care.

Method

Design

This study has a descriptive cross-sectional design using both quantitative and qualitative data. The study was approved by a regional ethics review board in Sweden (No. 2015/1517–31/5).

Study context and inclusion criteria

Data were collected at two specialized palliative home care services, each of which provided care for patients with life-threatening illness and palliative care needs, e.g., symptom management, and emotional and existential support, in two larger cities in different parts of Sweden. Both services were staffed by intra-professional teams (nurses, physicians, social workers, physical and occupational therapists). Inclusion criteria were: spouse or partner to and living with a person who received specialized palliative home care at one of the two included services; 18 years or older; able to read and understand Swedish. In the Swedish healthcare system, general palliative care can be provided in most healthcare settings. Specialized palliative care is provided in hospices, specialized palliative in-patient wards and home care services. Hospital bed numbers are decreasing, and an increased number of patients are cared for in their homes [29]. A social insurance system ensures that family caregivers are provided with an allowance for a limited period from the government to care for a severely ill family member at home.

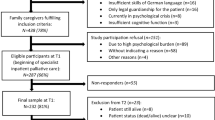

Procedure and data collection

All data were collected during 2016. Access to patient records was granted from the director of each department, and head nurses were asked to identify one family caregiver for each patient. Eligible family caregivers (n = 342) were identified via healthcare professionals and were contacted by the researchers with a letter sent by post requesting their participation, along with information about the study, a study-specific questionnaire, and a pre-paid stamped envelope for its return. The letter contained the phone number and email addresses of two of the researchers to allow participants to ask questions and receive oral information about the study. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary, and that data would be kept confidential. Altogether, 114 family caregivers returned the questionnaire with a signed consent form (response rate 33%).

The Questionnaire

The questionnaire included demographic questions and validated tools/instruments; the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) [30] and the Quality of Life in Life-Threatening Illness – Family caregiver version (QOLLTI-F) [31]. In addition, an open-ended question was included at the end of the questionnaire: “Do you have any thoughts about your situation, not covered in the questionnaire, that you want to share?”.

The CSNAT was developed in the UK based on interviews with family caregivers concerning their perspectives of key aspects of support needed while palliative care was provided at home. The resultant tool has 14 questions, based on broad domains covering practical, emotional, existential and social support, which are intended to capture a range of underlying support needs that are meaningful for family caregivers. The domains address family caregivers’ dual roles of being a provider of care (enabling support) and a person who is in need of support her/himself (direct support). There is an additional ‘anything else’ section enabling caregivers to add any support needs not covered by the existing domains. The tool has four response options about the need for more support, ranging from ‘no’ to ‘very much more’ [30]. For this study, the CSNAT was used as a ‘research tool’ to solely identify unmet support needs using the version that has been translated and validated among Swedish family caregivers [32].

The QOLLTI-F was developed in Canada based on interviews with family caregivers of patients with cancer, and focusing on what was experienced as important for their own QoL. The QOLLTI-F, version 2, includes a total of 17 items divided into 7 subscales assessing different domains: environment, patient condition, the family caregiver’s own state, family caregiver’s outlook, quality of care, relationships and financial worries. It also includes 1 item about overall QoL. All items are scored on an 11-point numeric rating scale, ranging between 0–10 with a descriptive anchor at each extreme. Each subscale is calculated by adding the responses and dividing the sum by the number of items in each domain. Thus, each subscale can range between 0–10, and after reversed items have been rescored, higher scores indicate higher levels of QoL [31]. The QOLLTI-F has been translated and validated among Swedish family caregivers [33]. The Cronbach’s alpha for the subscales that include more than one item were 0.58 for Environment, 0.87 for Family caregiver’s own state, 0.65 for Family caregiver’s outlook, 0.94 for Quality of care, and 0.76 for Relationships.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present the characteristics of the family caregivers and the study variables. A series of multiple linear regression analyses were used to explore associations between support needs and QoL. The QOLLTI-F scales were used as outcome variables while the CSNAT items were used as explanatory variables. As the CSNAT response scale have one category that implies no support need while the other categories reflect various levels of support need, the CSNAT items were dichotomized into ‘No support need’ (= 0) and ‘Support need’ (= 1). The regression models were adjusted for sex (female = 0; male = 1), age, and education no university degree (= 0; university degree = 1). For all tests, p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were conducted in Stata 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

The open-ended question was analysed with content analysis [34]. A total of 43 family caregivers (29 women and 14 men) provided comments that varied in length from a few lines to two extra pages. Many shared detailed, personal emotional experiences about their current situation, while others had written less, occasionally using strong expressions or words to share their views. In the initial reading of the comments it was found that they contained stories about their support needs and/or QoL. Next step was to read the text thoroughly to specifically search for various expressions. Associations between support needs and QoL were searched using the CSNAT and QOLLTI-F to help in identifying expressions concerning support needs and QoL. Data were coded and grouped into categories that consisted of descriptions illustrating the associations.

Results

Family caregiver characteristics

The sample consisted of 114 family caregivers with a mean age of 67.5 (SD = 10.9) years. Most participants were women (n = 69, 61%). In general, participants were well educated, with 42% (n = 47) having a university degree. The majority (n = 68, 61%) were retired, and about one-third (n = 32, 29%) were employed. A minority (n = 13, 12%) had children in the household. One-fifth (n = 22, 20%) reported receiving care benefits, i.e., they were paid by the Swedish government to provide care for the patient at home. Most of the patients had a cancer diagnosis (n = 96, 84%) or a cardiopulmonary disease (n = 15, 13%) (Table 1).

Family caregivers’ support needs and quality of life

The four domains where more than 50% of the family caregivers reported a need for more support were: Knowing what to expect in the future (69%), Having time for oneself in the day (66%), Dealing with feelings and worries (63%) and Practical help in the home (51%). Family caregivers were least likely to report the need for more support with Beliefs or spiritual concerns (21%) (Fig. 1).

The domain where family caregivers reported the poorest QoL was about Patient condition (Mdn = 3.5, q1–q3 = 1.75–7), followed by Family caregiver’s own state (Mdn = 6, q1–q3 = 4.6–8) and Family caregiver’s outlook (Mdn = 6, q1–q3 = 4.6–8). They reported on average the highest level of QoL in the domain Financial worries (Mdn = 9, q1–q3 = 5–10) and Quality of care (Mdn = 8.6, q1–q3 = 7.6–10). The median score on the domain Overall quality of life was 5 (q1–q3 = 3–8) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Associations between domains of support needs and domains and overall quality of life

In general, higher levels of need for more support were significantly associated with poorer QoL. All of the domains of support needs were significantly associated with one or more QoL domains; in particular: practical help in the home (CSNAT 12, B = -1.31 to -2.33), dealing with feelings and worries (CSNAT 6, B = -1.17 to -1.51), talking with your relative about his or her illness (CSNAT 11, B = -1.03 to -1.82), having time for yourself during the day (CSNAT 2, B = -1.25 to -1.88), equipment to help care for your relative (CSNAT 9, B = -0.98 to 1.87), and your beliefs or spiritual concerns (CSNAT 10, B = -1.10 to -2.65). None of the domains of support needs were significantly associated with the QoL domain Patient condition, while 11 of 14 were associated with the domain Family caregiver’s own state (B = -0.93 to -1.59) (Table 3).

Family caregivers’ comments – reflecting associations between support needs and quality of life

The analysis of comments revealed that, especially, the need for more support in Looking after one’s own health, Dealing with feelings and worries and Having time for oneself appeared to be associated with family caregivers’ QoL.

Own health and quality of life

Family caregivers commented that they needed more support with looking after their own health as they often prioritised the patient over themselves. They had to support the patient both emotionally and physically, resulting in neglecting their own health. Their situation, with limited sleep and increased care responsibilities at home, made them feel extremely tired, affecting their QoL in terms of both physical and emotional health. A 55-year-old woman wrote that she was on full-time sick leave while caring for her husband. She did not dare sleep at night and that clearly affected her own health. Some caregivers already had severe health problems of their own, which had worsened due to their situation. A 86-year-old woman wrote: “My back pain and breathlessness had become much worse because of the care of my husband”. Alternatively, those who wrote that they continued to look after their own health with, for example, recreational or sport activities, believed that it made them feel physically and mentally healthier. A 71- year-old man described that three times a week, he went to the gym and occasionally played in an orchestra. He prioritized these activities more than anything else.

Dealing with feelings and worries and quality of life

Many comments were about feelings and worries related to their current life and to the future.

Family caregivers feared that their support and care would not be sufficient to relieve the patient’s symptoms. One woman, aged 66 years, wrote: “How much medicine do I dare to use and combine? What helps and what can be the opposite? When it lasts for several hours it takes time to dare to relax before the next round of pain comes”. The comments revealed that they needed more support to deal with worries for the unknown future and how things would be if the situation did not improve. A 53-year-old woman reported that she was constantly worried about their uncertain situation and her ill husband, not knowing how long he would live and whether he would suffer from his illness. These kinds of worries were written by many, and the comments also concerned thoughts about how they would manage to be involuntarily alone. All these concerns clearly impacted their QoL.

Having time for oneself and quality of life

Family caregivers wrote about how they, due to their caregiving situation, needed support to find time for themselves during the day. Some could not leave the patient alone at home. Many had the main responsibility for care around the clock and those with small children wrote that help with taking care of the children would have been helpful. A 55-year-old woman described her situation: “Absolutely no time for myself since I take care of the children at the same time. It goes on, without any break”. This was also raised by a 50-year-old man: “In my case I have a 1,5-year old child which makes the whole situation much more stressful”. Family caregivers’ support needs in finding time for themselves was also related to their relationship with the patient. Their spousal relationship was already strained by the new caregiver relationship, and the lack of time for themselves contributed further to stressful interactions between them. Family caregivers also needed time for themselves to take care of other relationships that were important to them.

Discussion

This study found that higher levels of support needs were significantly associated with poorer QoL in family caregivers who cared for a spouse receiving specialised palliative care at home. All of the support domains on CSNAT were significantly associated with one or more QoL domains in QOLLTI-F, with the exception of QoL related to distress about the patient’s condition. However, family caregivers described in the open-ended question that their life was disrupted by the patient’s life-threatening illness and it affected their QoL relating to both physical and emotional health.

Family caregivers in the present study reported most need of additional support with Knowing what to expect in the future and Having time for yourself in the day. This is in line with the results from a study using the CSNAT among Swedish family caregivers of patients going through allogenic stemcell transplantion [35] and family caregivers in United Kingdom [30], Australia [36] and China [37]. Lowest QoL was reported in the QOLLTI-F domains related to the Patient condition, and Family caregivers’ own state. This indicates a need for more knowledge about the disease and how it will potentially affect the patient’ and the family caregivers’ future. The lack of this knowledge in turn seems to affect their QoL.

The majority of the CSNAT domains where more support was needed were associated with lower QoL related to the family caregivers’ own state, as they prioritised the patient’s needs over their own. Palliative care philosophy and definition stresses that patients and their family caregivers should be seen as the unit of care [38]. While this should suggest the family caregiver is supported, this is not always the case. The family caregiver and the patient have different needs, yet the patient’s views in fact often take precedence over those of the family caregiver, thus resulting in a risk that family caregivers’ views or needs are not taken into account [39, 40]. In addition, many family caregivers are reluctant to express difficulties or disclose their own needs to healthcare professionals and to ask for help [41]. In the present study, several free-text comments were related to psychological burden, social isolation and reduced time caused by caregiving responsibilities. They stressed the need for respite care or some own free time. This discrepancy between the lack of support opportunities and the desire for more free time has the potential to increase the burden for family caregivers in need of more time off [42]. Allocation of support is also dependent on whether family caregivers clearly express their need for support [43]. This suggests that it is important for healthcare professionals to pay attention to, assess and support family caregivers with their own support needs to successfully promote their QoL.

The top four support needs reported by family caregivers were each associated with poorer QoL in most of the QoL domains. A recent study found all CSNAT domains to be associated with a negative impact of the overall QoL [37]. In the present study, support needs, where unmet support needs were within the “direct” support domains, family caregivers’ QoL was affected. This is in line with previous research that shows that family caregivers, in addition to information and educational needs, also need support from healthcare professionals to prioritise caring for their own health and well-being [44].

The present study found no association between family caregivers’ need for more support and their QoL related to distress concerning the Patient condition, even though almost half reported that they wanted more support with Understanding their relative’s illness. Consistent with the results of other studies [45, 46], many family caregivers in the present study commented that they were constantly worried about how the illness would affect them both in the future, whether the patient would suffer, and how they would be able to manage the symptoms. When the illness progresses to a more advanced stage and patient care becomes more complex, the family caregivers’ distress often increases [45, 47] as more demands are placed on them [48]. In addition, family caregivers often face further distress when witnessing the dying process, which is often accompanied by physical deterioration and the patient’s loss of dignity [13, 45], and the higher amount of time that family caregivers devote to the patient is associated with poorer QoL [49]. In line with this, family caregivers in the present study reported the poorest QoL within the domain related to concerns about the Patient’s condition, which is also highlighted in the comments. These findings are interesting in relation to the fact that the QOLLTI-F itself takes into account how the QoL of family caregivers is affected by the distress related to the patient’s condition [31]. Thus, in the present study, performed in a specialized palliative care context, one could see that the patient’s condition does affect the family caregiver, but it was not associated with their need for more support, even though the CSNAT identifies support needs to provide care for the patient. Consequently, it could be assumed that patients received high quality care with adequate symptom management provided by the specialized palliative homecare settings. In addition, it should be noted that the CSNAT tool specifically focuses on the family caregiver and what support he or she needs to provide care or to maintain their own well-being. However, the patient and the family caregiver’s situation are interwoven, and they are both faced with considerable stress from physical symptoms and psychosocial burdens. They use multiple forms of coping through the illness trajectory that can help them manage the disease and related symptoms [50]. The family caregivers in this study may already have learned how to use problem-focused strategies for active management of practical stressors but have more difficult to handle the emotional distress.

To better understand this study’s results, family caregivers’ support needs and QoL can be enhanced by using theory. Andershed and Ternestedt’s (1999; 2001) theoretical framework focuses on the involvement and principal needs of family caregivers in palliative care [51, 52]. When family caregivers feel confirmed, informed and well supported by healthcare professionals, it increases the possibility that better QoL for both patients and family caregivers can be promoted, and facilitates the conditions necessary for providing meaningful care. In order to achieve this, family caregivers need support according to the three key concepts; “Knowing” (informational needs), “Being” (existential and emotional needs) and “Doing” (practical needs). All three of these key concepts can be found in the reported support and QoL domains in this study. However, the relationship between the three key concepts and the support and QoL domains is not a simple direct relationship. “Support with knowing what to expect in the future” may, for instance, be about a need for information (knowing), but could also be about emotional support and existential concerns in terms of anxiety about an uncertain future (being), or about finding out what practical measures need to be put in place as the patient deteriorates (doing). Such is the broad nature of the domains that further information, and emotional or practical support may be required for any of the domains, depending on the underlying support needs that the caregiver expresses, which in turn will affect their QoL.

Methodological considerations

This study has some limitations that need to be considered. First, the cross-sectional design did not allow for any conclusions about the causal relationships between the variables. Second, the study was based on questionnares with closed-ended questions; only one open-ended question to explore the family caregivers situation was included.

The internal consistency assessed by Cronbach’s alpha was low for the Envoronment and Family caregiver’s outlook subscales in the QOLLTI-F. This was partly expected since both scales consists of few items, which decresed the Cronbach’s alpha coeffiicient [53]. In addition, both subscales demontreted low internal consitency reliability in the development of the QOLLTI-F [54]. Also, the response rate was low and, as the ethics approval did not include asking caregivers to provide their reasons for declining, no information exists about whether those declining differed from those who participated; however, it might be due to the stressful situation of caregiving. The sample in this present study had a high educational level and most were born in Sweden. They also received economic benefits from the government and the treatments provided by the palliative homecare service were free of charge. It is a well-known fact that family caregivers who are coping well are more likely to take part in research than those who are more vulnerable, which also means that this study may not capture the full representation of family caregivers [55]. Despite this limitation, the chosen methods reveal that there are subtle and nuanced relationships between family caregivers’ needs for more support and their QoL that may be even more pronounced in those who are less likely to take part in research.

Conclusions and clinical implications

This study, performed in specialised palliative home care, shows associations between family caregiver’s need for more support and their QoL. Higher levels of support needs were significantly associated with poorer QoL for family caregivers. This gives additional weight to the importance of addressing the family caregivers’ needs for support. In this research, CSNAT was used as a research tool. For use in practice, the CSNAT is a communication tool that is integrated into a person-centered process of assessment and support. The response categories can facilitate communication with opportunities to express individual problems and concerns enabling more tailored support to address family caregivers’ specific needs that can enable healthcare professionals to give individual support to them. With a deeper understanding of the complexities of supporting family caregivers in palliative care, healthcare professionals are better placed to increase family caregivers’ QoL.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CSNAT:

-

The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- QOLLTI-F:

-

Quality of Life in Life-Threatening Illness – Family caregiver version

References

Kelley AS, Sean MR. Palliative care for the seriously Ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):747–55.

World Health Organization. WHOQOL: measuring quality of life. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqolqualityoflife/en/.

Pivodic L, Pardon K, Morin L, Addington-Hall J, Miccinesi G, Cardenas-Turanzas M, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Naylor W, Ruiz Ramos M, Van den Block L, et al. Place of death in the population dying from diseases indicative of palliative care need: a cross-national population-level study in 14 countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(1):17–24.

Reigada C, Pais-Ribeir JL, Novella A, Gonçalves E. The caregiver role in palliative care: a systematic review of the literature. Health Care Curr Rev. 2015;3(2).

Gomes B, Calanzani N, Gysels M, Hall S, Higginson IJ. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:7.

Khan SA, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. End-of-life care–what do cancer patients want? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(2):100–8.

Woodman C, Baillie J, Sivell S. The preferences and perspectives of family caregivers towards place of care for their relatives at the end-of-life. A systematic review and thematic synthesis of the qualitative evidence. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6(4):418.

Holtslander L, Baxter S, Mills K, Bocking S, Dadgostari T, Duggleby W, Duncan V, Hudson P, Ogunkorode A, Peacock S. Honoring the voices of bereaved caregivers: a metasummary of qualitative research. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16(1):48.

Palmer Kelly E, Meara A, Hyer M, Payne N, Pawlik TM. Understanding the type of support offered within the caregiver, family, and spiritual/religious contexts of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(1):56–64.

Ferrell BR, Kravitz K, Borneman T, Friedmann ET. Family caregivers: a qualitative study to better understand the quality-of-life concerns and needs of this population. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(3):286–94.

Holm M, Henriksson A, Carlander I, Wengström Y, Öhlen J. Preparing for family caregiving in specialized palliative home care: an ongoing process. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(3):767–75.

Lund L, Ross L, Petersen MA, Groenvold M. Cancer caregiving tasks and consequences and their associations with caregiver status and the caregiver’s relationship to the patient: a survey. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):1–13.

McDonald J, Swami N, Pope A, Hales S, Nissim R, Rodin G, Hannon B, Zimmermann C. Caregiver quality of life in advanced cancer: qualitative results from a trial of early palliative care. Palliat Med. 2018;32(1):69–78.

Harding R, Epiphaniou E, Hamilton D, Bridger S, Robinson V, George R, Beynon T, Higginson IJ. What are the perceived needs and challenges of informal caregivers in home cancer palliative care? Qualitative data to construct a feasible psycho-educational intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(9):1975–82.

McIlfatrick S, Doherty LC, Murphy M, Dixon L, Donnelly P, McDonald K, Fitzsimons D. ‘The importance of planning for the future’: Burden and unmet needs of caregivers’ in advanced heart failure: A mixed methods study. Palliat Med. 2018;32(4):881–90.

Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, Friederich HC, Huber J, Thomas M, Winkler EC, Herzog W, Hartmann M. When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121(9):1513–9.

Friðriksdóttir N, Saevarsdóttir T, Halfdánardóttir S, Jónsdóttir A, Magnúsdóttir H, Olafsdóttir KL, Guðmundsdóttir G, Gunnarsdóttir S. Family members of cancer patients: Needs, quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(2):252–8.

Kim Y, Carver CS. Unmet needs of family cancer caregivers predict quality of life in long-term cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(5):749–58.

Vachon M. “It made me more human”: existential journeys of family caregivers from prognosis notification until after the death of a loved one. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:1613–8.

Gotze H, Brahler E, Gansera L, Schnabel A, Gottschalk-Fleischer A, Kohler N. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in family caregivers of palliative cancer patients during home care and after the patient’s death. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(2):e12606.

Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Spouses, adult children, and children-in-law as caregivers of older adults: a meta-analytic comparison. Psychol Aging. 2011;26(1):1–14.

Rha SY, Park Y, Song SK, Lee CE, Lee J. Caregiving burden and the quality of life of family caregivers of cancer patients: the relationship and correlates. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(4):376–82.

Breen LJ, O’Connor M, Johnson AR, Aoun SM, Howting D. Effect of caregiving at end of life on grief, quality of life and general health: a prospective, longitudinal, comparative study. Palliat Med. 2019;34:145–54.

Hudson P, Payne S. Family caregivers and palliative care: current status and agenda for the future. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(7):864–9.

Norinder M, Goliath I, Alvariza A. Patients’ experiences of care and support at home after a family member’s participation in an intervention during palliative care. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15(3):305–12.

Touzel M, Shadd J. Content validity of a conceptual model of a palliative approach. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(11):1627–35.

Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, Tan J-Y. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):96.

Perpiñá-Galvañ J, Orts-Beneito N, Fernández-Alcántara M, García-Sanjuán S, García-Caro MP, Cabañero-Martínez MJ. Level of burden and health-related quality of life in caregivers of palliative care patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4806.

National Board of Health and Welfare. Open comparisons 2020 – six questions about health care – overall indicator-based follow-up of health care results (Öppna jämförelser 2020 – Sex frågor om vården – Övergripande indikatorbaserad uppföljning av hälso- och sjukvårdens resultat). 2020; (2020–1–6544). Retrieved from https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepointdokument/artikelkatalog/oppna-jamforelser/2020-1-6544.pdf.

Ewing G, Grande G. Development of a carer support needs assessment tool (CSNAT) for end-of-life care practice at home: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2013;27(3):244–56.

Cohen R, Leis AM, Kuhl D, Charbonneau CC, Ritvo P, Ashbury FD. QOLLTI-F: measuring family carer quality of life. Palliat Med. 2006;20(8):755–67.

Alvariza A, Holm M, Benkel I, Norinder M, Ewing G, Grande G, Hakanson C, Ohlen J, Arestedt K. A person-centred approach in nursing: Validity and reliability of the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;35:1–8.

Axelsson L, Alvariza A, Carlsson N, Cohen SR, Sawatzky R, Årestedt K. Measuring quality of life in life-threatening illness – content validity and response processes of MQOL-E and QOLLTI-F in Swedish patients and family carers. BMC Palliative Care. 2020;19(1):1–9.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Kisch AM, Bergkvist K, Alvariza A, Årestedt K, Winterling J. Family caregivers’ support needs during allo-HSCT—a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(6):3347–56.

Aoun SM, Ewing G, Grande G, Toye C, Bear N. The impact of supporting family caregivers before bereavement on outcomes after bereavement: adequacy of end-of-life support and achievement of preferred place of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):368–78.

Zhou S, Zhao Q, Weng H, Wang N, Wu X, Li X, Zhang L. Translation, cultural adaptation and validation of the Chinese version of the carer support needs assessment tool for family caregivers of cancer patients receiving home-based hospice care. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20(1):1–10.

World Health Organization. National cancer control programmes: policies and managerial guidelines. Geneva: WHO; 2002.

Pottle J, Hiscock J, Neal RD, Poolman M. Dying at home of cancer: whose needs are being met? The experience of family carers and healthcare professionals (a multiperspective qualitative study). BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10(1):e6.

Tarberg AS, Kvangarsnes M, Hole T, Thronæs M, Madssen TS, Landstad BJ. Silent voices: family caregivers’ narratives of involvement in palliative care. Nurs Open. 2019;6(4):1446–54.

Funk L, Stajduhar KI, Toye C, Aoun S, Grande GE, Todd CJ. Part 2: Home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published qualitative research (1998–2008). Palliat Med. 2010;24(6):594–607.

Bijnsdorp FM, Pasman HRW, Boot CRL, van Hooft SM, van Staa A, Francke AL. Profiles of family caregivers of patients at the end of life at home: a Q-methodological study into family caregiver’ support needs. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):51.

Ateş G, Ebenau AF, Busa C, Csikos Á, Hasselaar J, Jaspers B, Menten J, Payne S, Van Beek K, Varey S, et al. “Never at ease” - family carers within integrated palliative care: a multinational, mixed method study. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):39.

Flemming K, Atkin K, Ward C, Watt I. Adult family carers’ perceptions of their educational needs when providing end-of-life care: a systematic review of qualitative research. AMRC Open Res. 2019;1(2):2.

Lobb EA, Bindley K, Sanderson C, MacLeod R, Mowll J. Navigating the path to care and death at home—it is not always smooth: a qualitative examination of the experiences of bereaved family caregivers in palliative care. J Psychosoc Oncol Res Pract. 2019;1(1):e3.

Oechsle K. Current advances in palliative & hospice care: problems and needs of relatives and family caregivers during palliative and hospice care-an overview of current literature. Med Sci. 2019;7(3):43.

Williams AL, McCorkle R. Cancer family caregivers during the palliative, hospice, and bereavement phases: a review of the descriptive psychosocial literature. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9(3):315–25.

Candy B, Jones L, Drake R, Leurent B, King M. Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;15(6):Cd007617.

Franchini L, Ercolani G, Ostan R, Raccichini M, Samolsky-Dekel A, Malerba MB, Melis A, Varani S, Pannuti R. Caregivers in home palliative care: gender, psychological aspects, and patient’s functional status as main predictors for their quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(7):3227–35.

Greer JA, Applebaum AJ, Jacobsen JC, Temel JS, Jackson VA. Understanding and addressing the role of coping in palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):915.

Andershed B, Ternestedt B-M. Development of a theoretical framework describing relatives’ involvement in palliative care. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34(4):554–62. 95.

Andershed B, Ternestedt BM. Involvement of relatives in care of the dying in different care cultures: development of a theoretical understanding. Nurs Sci Quart. 1999;12(1):45–51.

Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Cohen R, Leis AM, Kuhl D, Charbonneau C, Ritvo P, Ashbury FD. QOLLTI-F: measuring family carer quality of life. Palliat Med. 2006;20(8):755–67.

Holm M, Årestedt K, Carlander I, Wengström Y, Öhlen J, Alvariza A. Characteristics of the family caregivers who did not benefit from a successful psychoeducational group intervention during palliative cancer care: a prospective correlational study. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(1):76–83.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to give their sincere thanks to all family caregivers who so generously contributed.

The CSNAT is a copyright tool which requires a licence for its use. For details about accessing the CSNAT and the licensing process, please visit http://csnat.org.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linnaeus University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study. MN, AA and IB collected the data. Predominantly MN, AA, KÅ and MH analyzed and interpreted the data. MN were the main writer of the manuscript together with AA. All authors contributed in reviewing the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants received oral and written information about the aim of the study, the voluntarily nature of participation and their right to withdraw, before giving their written informed consent. Formal approval was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (No. 2015/1517–31/5).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Norinder, M., Årestedt, K., Lind, S. et al. Higher levels of unmet support needs in spouses are associated with poorer quality of life – a descriptive cross-sectional study in the context of palliative home care. BMC Palliat Care 20, 132 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00829-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00829-9