Abstract

Background

Disc repositioning by Mitek anchors for anterior disc displacement (ADD) combined with orthognathic surgery gained more stable results than when disc repositioning was not performed. But for hypoplastic condyles, the implantation of Mitek anchors may cause condylar resorption. A new disc repositioning technique that sutures the disc to the posterior articular capsule through open incision avoids the implantation of the metal equipment, but the stability when combined with orthognathic surgery is unknown. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the stability of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disc repositioning by open suturing in patients with hypoplastic condyles when combined with orthographic surgery.

Methods

Patients with ADD and jaw deformity from 2017 to 2021 were included. Disc repositioning by either open suturing or mini-screw anchor were performed simultaneously with orthognathic surgery. MRI and CT images before and after operation and at least 6 months follow-ups were taken to evaluate and compare the TMJ disc and jaw stability. ProPlan CMF 1.4 software was used to measure the position of the jaw, condyle and its surface bone changes.

Results

Seventeen patients with 20 hypoplastic condyles were included in the study. Among them, 12 joints had disc repositioning by open suturing and 8 by mini-screw anchor. After an average follow-up of 18.1 months, both the TMJ disc and jaw position were stable in the 2 groups except 2 discs moved anteriorly in each group. The overall condylar bone resorption was 8.3% in the open suturing group and 12.5% in the mini-screw anchor group.

Conclusions

Disc repositioning by open suturing can achieve both TMJ and jaw stability for hypoplastic condyles when combined with orthognathic surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anterior disc displacement (ADD) is a common temporomandibular disorder (TMD). The clinical manifestations are joint pain, clicking, and limited mouth opening. For some cases, conservative treatment such as medications, physiotherapy including low-intensity pulsed ultrasound etc. can achieve good results through masticatory biofeedback [1, 2]. Whereas in some cases, ADD may cause condylar resorption [3]. When ADD happens in juveniles, the growth of the condyle may be affected and cause mandibular asymmetry and/or retrognathia [4]. Studies have showed that ADD may increase jaw instability when combined with orthognathic surgery [5], especially for idiopathic condylar resorption (ICR) patients where the relapse rate has been reported from 83.3% to 100% [6]. To solve this problem, Wolford proposed disc repositioning when combined with orthognathic surgery [7] by Mitek anchors and gained more stable results than when disc repositioning was not performed [8,9,10,11]. Later, Yang et. al designed a self-inserted titanium mini-screw anchor (5 mm in length and 2 mm in diameter), with a slot at the end for bolting sutures [12, 13]. But for hypoplastic condyles which has normal morphology and structure but are diminished in size on radiographic examination [14], inserting a metal device (anchor) may interfere with the blood supply of the condyle and cause resorption. In 2001, Yang modified a disc suturing technique under the arthroscope which sutured the disc to the posterior articular capsule [15]. The follow-up results by MRI showed good stability [16]. Later, He used a similar technique as Yang through an open incision to avoid the need for special equipment and for ease of operation [17]. However, the stability of this suturing technique when combined with orthognathic surgery, especially for patients with hypoplastic condyles is unknown.

The purpose of the study was to evaluate TMJ and jaw stability after disc repositioning by open suturing when combined with orthognathic surgery, and to compare it to the Yang’s self-designed mini-screw anchor of disc repositioning for hypoplastic condyles.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective clinical study which was approved by the Shanghai 9th People’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (SH9H-2018-T88-2). The guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed in the present study. Patients treated with disc repositioning and simultaneous orthognathic surgery from January 2017 to January 2021 were enrolled in the study. The inclusion criteria were: 1) ADD with hypoplastic condyle (normal condylar morphology but small bone volume) and dentofacial deformity diagnosed by MRI and CT pre-operation; 2) TMJ disc repositioning by either open suturing or mini-screw anchor and concomitant orthognathic surgery (bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy, BSSRO ± Le Fort I); 2) operated by one surgeon (Dr. He); 3) MRI and CT data before and within 1 week after operation and at least 6 months follow-up. The exclusion criteria were: 1) ADD with normal condylar morphology and structure; 2) previous TMJ surgery; 3) total joint reconstruction on one side; 4) severely deformed discs which is unsalvageable.

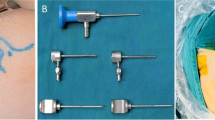

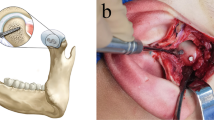

Surgical treatment was as follows: 1) disc repositioning by either open suturing to the posterior articular capsule [17] or mini-screw anchor [13] through modified preauricular small incision as we previously described (Fig. 1); 2) BSSRO was performed for all patients. Le Fort I osteotomy was lastly performed when indicated [18].

The TMJ and jaw stability after surgery were evaluated as the following measurements and compared between different disc repositioning methods.

Variables and measurements

TMJ stability

MRI scans were acquired by a 1.5-T imager (Signa, General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) with bilateral 3-inch TMJ surface coil receivers for all patients before and after operation and during follow-ups. Oblique sagittal images with closed- (proton density-weighted imaging, PDWI) and open-mouth (T2-weighted images, T2WI) positions and coronal images (T2WI) of the condyle were acquired for evaluation of disc position and condylar bone status [19]. When the posterior band of the disc was at the 1 to 2 o’clock position of the condyle, it was considered overcorrected and well positioned. When the posterior band of the disc was at the 12 o’clock position of the condyle, it was considered in a normal position. When the posterior band of the disc was anterior to the 12 o’clock position of the condyle and without reduction during mouth opening, it was considered not repositioned or relapsed [20]. The status of condylar bone was defined as bone deposition, no change and resorption.

Jaw stability

All patients had CT scans using their maximum intercuspal position (layer thickness, 1 mm; reconstruction layer thickness, 0.625 mm; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) and at three time points: preoperative (T0), within 1 week postoperative (T1) and the last follow-up (T2). The position of jaw, condyle and its surface bone changes were measured by ProPlan CMF 1.4 software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium, Figs. 2A-B). Definitions of three-dimensional (3D) bony landmarks for measurement were shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Measurement of the stability. A, superimposition of T0, T1 and T2 maxilla models using surface best fit registration; (B), coordinate system; (C), changes of B-Z between T1 and T2 reflect sagittal stability of mandible; (D), changes of B-Y between T1 and T2 reflect coronal stability of mandible; E and F, ΔGo-Y at T1 and T2 reflect mandibular symmetry

First, the segmentation function was used to perform 3D reconstruction of the maxillary model with cranial base and mandibular models at T0, T1 and T2 time intervals. As a fixed structure, the cranial base was used for superimposition of T1 and T2 maxillary models to T0 by using surface-best-fit registration as reported by Wan et al. [21]. The position of the maxilla and mandible at different time intervals (T0, T1 and T2) were then compared. The coordinate system was established as: Y plane (sagittal plane): passing through N, S and Ba; FH plane: passing through Or and Po and perpendicular to Y plane; X plane (horizontal plane): passing through N and parallel to FH plane; Z plane (coronal plane): passing through N and perpendicular to X plane and Y plane.

Stability of the distal segment of the mandible was measured by the position change of point B in the three-dimensional coordinate system. Stability of the proximal segment of the mandible was measured by condylar rotation and the symmetry of GoR/GoL in the three-dimensional coordinate system. Changes of B-Z between T1 and T2 reflect sagittal stability of the mandible. Changes of B-Y between T1 and T2 reflect coronal stability of the mandible. ΔGo-Y at T1 and T2 reflect mandibular symmetry (Figs. 2C-F). Condylar rotation was described by measuring the changes of Pitch, Roll and Yaw between T1 and T2 mandibular models (Figs. 3A-C). Maxillary stability was measured by the changes of pitch, roll and yaw in the three-dimensional coordinate system between T1 and T2 maxillary models (Figs. 3D-F).

Condylar position and surface bone remodeling were measured by the position changes of corresponding points between T1 and T2 mandibular models (Figs. 4A-B). In order to distinguish between condylar movement and remodeling, we superimposed T1 and T2 mandibular models using surface-best-fit registration based on the following area of the mandible that are the least affected by bone remodeling after surgery: 1) the posterior area of mandible ramus above the lingua and below the condyle neck; and, 2) the coronoid process [22]. After superimposition, we obtained a registered T2 mandibular model (T2r, Figs. 4C-D). Condylar movement was measured by changes of CoT-X, CoT-Y, CoT-Z between T2r and T2 mandibular models (Figs. 4E-F) and condylar remodeling was measured by changes of CoT-X, CoL-Y, CoM-Y, CoA-Z, CoP-Z between T2r and T2 mandibular models after surgery and during follow-ups (Figs. 3C-D).

Measurement of the condylar position. A-B, position changes of correspondent points on condyle between T1 and T2 reflect both condylar movement and remodeling; (C-D), superimposition of T1 and T2 mandibular models using surface-best-fit registration to measure condylar remodeling; (E–F), Changes of CoT-X, CoT-Y, CoT-Z between T2r and T2 mandible model reflect vertical, lateral and antero-posterior movement of the condyle during follow-up

Statistical analysis

Jaw stability, condylar movement and surface bone remodeling in open suturing group and mini-screw anchor group within 1 week after surgery and at the last follow-up were compared by paired t test in SPSS 17.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Independent t test was used to analyze the differences between open suturing and mini-screw anchor groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Seventeen patients were included in the study. There were 3 males and 14 females ranging in age from 19 to 28 years (mean = 23.1). All patients had TMJ symptoms of joint pain, noises, or mouth opening limitation. Their average follow-up period was 18.7 months (6 to 38 months). Among them, 9 patients with 12 joints had disc repositioned by open suturing, and the other 8 patients with 8 joints by mini-screw anchor. There were 10 patients combined with Le fort I + BSSRO and 7 patients with only BSSRO to correct jaw deformity (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, Table 4). Eight patients were prepared orthodontically to the surgery (4 in suturing group and 4 in mini-screw anchor group). Five patients had “surgery first” and received orthodontic treatment after surgery (2 in suturing group and 3 in mini-screw anchor group). Four patients didn’t receive orthodontic treatment before and after surgery (3 in suturing group and 1 in mini-screw anchor group).

Imaging examinations of patient in Fig. 5. A, MRI showed right anterior disc displacement without reduction before surgery; (B), the disc was repositioned after surgery; (C), the disc was in position at 1.5 years follow-up with significant bone deposition; (D), CT showed right condyle had a reduction in volume before surgery; (E), significant bone deposition was shown at 1.5 years follow-up. Red arrows indicate TMJ disc

CT measurement of the patient in Fig. 5. A, E, front view before surgery; (B), (F), immediate after surgery; (C), (G), 1.5 years follow-up; (D), superimposition of T1 and T2 maxilla models show stable maxilla position. (H), superimposition of T1 and T2 mandible models showed bone deposition on the right condyle and stable mandible position

Occlusion of the patient in Fig. 8. A-C, preoperative occlusion; (D)-(F), postoperative occlusion after orthodontic treatment

Radiographs of the patient in Fig. 8. A, D, F, preoperative imaging; (B), postoperative MRI; (E), (G), X-rays after orthodontic treatment. Red arrows indicate TMJ disc

The first outcome of this study was the difference in TMJ stability using suturing compared to mini-screw fixation. MRI showed that all the 21 anteriorly displaced discs were repositioned after operation. During follow-ups, 19 discs were in good position but 2 moved anteriorly, including 1 in open suturing group and 1 in mini-screw anchor group. In the open suturing group, 8 condyles had bone deposition (66.7%), 3 had no change (25%) and 1 had a slight bone resorption (8.3%). In the mini-screw anchor group, 3 condyles had bone deposition (37.5%), 4 had no change (50%) and 1 had a slight bone resorption (12.5%). Condylar bone was more stable in the open suturing group than mini-screw anchor group (91.7% vs. 87.5%, Table5). Two condyles with slight bone resorption had anteriorly disc relapse.

The second outcome was jaw stability after disc repositioning by open suturing or mini-screw anchor for hypoplastic condyles when combined with orthognathic surgery. CT measurement showed that there were no significant jaw position changes in both open suturing and mini-screw anchor groups during follow-up (p > 0.05, Table 6). Although immediately after surgery, condyles after disc repositioning moved significantly downward (average of 1.57 mm, p = 0.000) and laterally (average of 1.12 mm, p = 0.007), and at the last follow up, they moved upward (average of 1.24 mm, p = 0.000), medially (average of 0.73 mm, p = 0.009) and posteriorly (average of 1.16 mm, p = 0.001, Table 7), jaw stability was not affected. At the last follow-up, condyles after disc repositioning showed significant bone deposition on the medial surface (p = 0.043, Figs. 6C, E 10C and Table 8). There was no significant bone resorption in the two groups (p > 0.05, Table 9).

Discussion

The TMD prevalence is increasing, especially during pandemic COVID 19, therefore new treatment methods are especially needed [23]. As the most common type of TMD, presurgical ADD is an important factor for the relapse of orthognathic surgery [24, 25]. Disc repositioning for ADD when combined with orthognathic surgery by Mitek anchors have been reported with stable results [7,8,9,10,11]. In this study, we tried a new method of disc repositioning by open suturing for hypoplastic condyles when combined with orthognathic surgery. Instead of inserting a metal anchor to the condyle, we used non-absorbable suture to fix the disc into the posterior capsule. The advantage of this method is no disturbance of the blood supply to the condyle during dissection. The disadvantage is the stability of fixation the disc to soft tissue instead of bone, especially when the jaw was split and moved during orthognathic surgery. We used MRI and CT measurements to evaluate TMJ and jaw stability in this study. The results showed that both techniques (open suturing and mini-screw anchor) for disc repositioning on hypoplastic condyles can acquire stable TMJ and jaw position when combined with orthognathic surgery.

TMJ stability was evaluated by MRI which is a golden standard for disc position and bone status. After orthognathic surgery, each group had 1 disc relapsed anteriorly and slight bone resorption. Compared with mini-screw anchor, open suturing had more condylar bone deposition (66.7% vs. 37.5%), and less bone resorption (8.3% vs. 11.1%) with an overall more condylar bone stability (91.7% vs. 87.5%). Gomes et al. found after disc repositioning by Mitek anchors when combined with orthognathic surgery, the overall condylar volume tended to reduce and over 30% of the cases showed more than 1.5 mm of bone resorption on at least one surface of the condyle [8]. But he did not describe the jaw stability. In our study, we also found 12.5% of the hypoplastic condyles with ADD had slight bone resorption about 1 mm after disc repositioning by Yang’s self-designed mini-screw anchor, but the jaw stability was not affected. So far, there is no report on the correlation between the degree of condylar resorption and jaw stability with orthognathic surgery. How much condylar resorption which affects jaw stability needs further study.

After TMJ disc repositioning, the condyle moved downward and laterally, but during follow-ups, it moved upward, medially and posteriorly. This is because of the reduction of postsurgical swelling and disc reshaping developed as Chen and Gomes reported [26, 27]. Although the condyle moved a little bit, the patient’s jaw position and occlusion were stable within the range of compensation.

Small sample size and the predominance of women in the group were the limitations of this study. Since it was a preliminary study on the new disc repositioning method by open suturing when combined with orthognathic surgery, we only tried a small number of patients to see if it was stable before large number of patients performed. According to the pilot data, a prospective study will be designed in the future including adequate number of patients for further analysis.

Conclusions

Disc repositioning by open suturing can acquire stable TMJ and jaw position when combined with orthognathic surgery. The condyles had good adaptative changes after surgery during mandibular function.

Availability of data and materials

The data collected and analyzed in the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADD:

-

Anterior disc displacement

- TMJ:

-

Temporomandibular joint

- ICR:

-

Idiopathic condylar resorption

- BSSRO:

-

Bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy

References

Namera MO, Mahmoud G, Abdulhadi A, Burhan A. Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) applied on the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) region on the functional treatment of class II malocclusion: A randomized controlled trial. Dent Med Probl. 2020;57(1):53–60.

Florjanski W, Malysa A, Orzeszek S, Smardz J, Olchowy A, Paradowska-Stolarz A, Wieckiewicz M. Evaluation of Biofeedback Usefulness in Masticatory Muscle Activity Management-A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):766.

Wolford LM, Gonçalves JR. Condylar resorption of the temporomandibular joint: how do we treat it? Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2015;27(1):47–67.

Manfredini D, Segù M, Arveda N, Lombardo L, Siciliani G, Rossi Alessandro, Guarda-Nardini L. Temporomandibular joint disorders in patients with different facial morphology. A systematic review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74(1):29–46.

Al-Moraissi EA, Wolford LM. Does temporomandibular joint pathology with or without surgical management affect the stability of counterclockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex in orthognathic surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(4):805–21.

Mitsimponas K, Mehmet S, Kennedy R, Shakib K. Idiopathic condylar resorption. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;56(4):249–55.

Goncalves JR, Cassano DS, Wolford LM, Marquez IM. Postsurgical stability of counterclockwise maxillomandibular advancement surgery: affect of articular disc repositioning. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66(4):724–38.

Bianchi J, Porciúncula GM, Koerich L, Ignácio J, Wolford LM, Gonçalves JR. Three-dimensional stability analysis of maxillomandibular advancement surgery with and without articular disc repositioning. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46(8):1348–54.

Gomes LR, Cevidanes LH, Gomes MR, Ruellas AC, Ryan DP, Paniagua B, Wolford LM, Gonçalves JR. Counterclockwise maxillomandibular advancement surgery and disc repositioning: can condylar remodeling in the long-term follow-up be predicted? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46(12):1569–78.

Goncalves JR, Wolford LM, Cassano DS, da Porciuncula G, Paniagua B, Cevidanes LH. Temporomandibular joint condylar changes following maxillomandibular advancement and articular disc repositioning. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(10):1759.e1-15.

Wolford LM, Karras S, Mehra P. Concomitant temporomandibular joint and orthognathic surgery: A preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60(4):356–62.

Zhang S, Liu X, Yang X, Yang C, Chen M, Haddad MS, Chen Z. Temporomandibular joint disc repositioning using bone anchors: an immediate post surgical evaluation by magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:262.

He D, Yang C, Zhang S, Wilson JJ. Modified temporomandibular joint disc repositioning with miniscrew anchor: part I–surgical technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(1):47.e1-47.e479.

Liu YS, Yap AU, Lei J, Liu MQ, Fu KY. Association between hypoplastic condyles and temporomandibular joint disc displacements: a cone beam computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging metrical analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;49(7):932–9.

Yang C, Cai XY, Chen M, Zhang SY. New arthroscopic disc repositioning and suturing technique for treating an anteriorly displaced disc of the temporomandibular joint: part I–technique introduction. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41(9):1058–63.

Liu X, Zheng J, Cai X, Abdelrehem A, Yang C. Techniques of Yang’s arthroscopic discopexy for temporomandibular joint rotational anterior disc displacement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48(6):769–78.

He D, Yang C, Zhu H, Ellis E 3rd. Temporomandibular joint disc repositioning by suturing through open incision: A technical note. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;76(5):948–54.

Lu C, Xie Q, He D, Yang C. Stability of orthognathic surgery in the treatment of condylar osteochondroma combined with jaw deformity by CT measurements. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78(8):1417.e1-14.

Dong M, Jiao Z, Sun Q, et al. The magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of condylar new bone remodeling after Yang’s TMJ arthroscopic surgery. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5219.

Zhou Q, Zhu H, He D, Yang C, Song X, Ellis E 3rd. Modified temporomandibular joint disc repositioning with mini-screw anchor: Part II—Stability evaluation by magnetic resonance imaging. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77(2):273–9.

Wan Z, Shen SG, Gui H, Zhang P, Shen S. Evaluation of the postoperative stability of a counter-clockwise rotation technique for skeletal class II patients by using a novel three- dimensional position-posture method. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):13196.

Claus JDP, Koerich L, Weissheimer A, Almeida MS, Belle de Oliveira R. Assessment of condylar changes after orthognathic surgery using computed tomography regional superimposition. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48(9):1201–8.

Emodi-Perlman A, Eli I. One year into the COVID-19 pandemic - temporomandibular disorders and bruxism: What we have learned and what we can do to improve our manner of treatment. Dent Med Probl. 2021;58(2):215–8.

Al-Moraissi EA, Wolford LM, Perez D, Laskin DM, Ellis E 3rd. Does orthognathic surgery cause or cure temporomandibular disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(9):1835–47.

Sansare K, Raghav M, Mallya SM, Karjodkar F. Management-related outcomes and radiographic findings of idiopathic condylar resorption: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(2):209–16.

Chen XZ, Qiu YT, Zhang SY, Zheng JS, Yang C. Changes of the condylar position after modified disk repositioning: A retrospective study based on magnetic resonance imaging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020;129(1):14–20.

Gomes LR, Soares Cevidanes LH, Gomes MR, Carlos de Oliveira Ruellas A, Obelenis Ryan DP, Paniagua B, Wolford LM, Gonçalves JR. Three-dimensional quantitative assessment of surgical stability and condylar displacement changes after counterclockwise maxillomandibular advancement surgery: Effect of simultaneous articular disc repositioning. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;154(2):221–33.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Edward Ellis 3rd for the help of revising the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Clinical plus project of Shanghai 9th People’s Hospital (JYLJ201805), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality Science Research Project (20Y11903900, 20S31902500).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DH designed the study and performed all the operations. JH, JZ and CL collected the data. JH analyzed the data and wrote the draft. DH revised the the paper. ZY did the orthodontic treatment. All authors were contributed in the paper and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Affiliated 9th People’s Hospital (SH9H-2018-T88-2) and informed consent was taken from all individual participants.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the participants.

Competing interests

All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hua, J., Lu, C., Zhao, J. et al. Disc repositioning by open suturing vs. mini-screw anchor: stability analysis when combined with orthognathic surgery for hypoplastic condyles. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 23, 387 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05337-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05337-2