Abstract

Background

Pain relief is likely to be the most important long-term outcome for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA). However, research indicates that persistent pain (> 3 months) is a considerable problem, affecting up to 34 % of patients. Pain catastrophizing might contribute to acute and persistent pain experienced after surgery. The primary aim of the present study was to examine the association between preoperative pain catastrophizing and postoperative pain in patients undergoing TKA up to one year after surgery. Second, we wanted to investigate a possible shift in postoperative catastrophizing.

Methods

In this prospective cohort study, 71 TKA patients were included consecutively between January and June 2013. Pain was assessed with the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and the item “average pain” was used as the main outcome. Pain catastrophizing was measured by the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS). Questionnaires were completed prior to surgery (baseline) and at two days, two weeks, eight weeks and one year postoperatively.

Results

Mean (SD) preoperative pain score was 5.4 (2.2), reduced to 2.9 (2.3) after eight weeks and 2.4 (2.4) after one year (p < 0.001). The overall median preoperative PCS score was 17.0 (7.8–28.3). The overall model estimated PCS mean score was 7.6 at eight weeks and 6.5 at one year follow-up. The results at eight weeks and one year follow-up were both significantly lower than the preoperative value (p < 0.001). The preoperative PCS score was not associated with the postoperative pain score (p = 0.942), while preoperative pain was a significant covariate in the mixed linear model (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

No associations were found between preoperative pain catastrophizing and pain eight weeks or one year after surgery. The decrease in PCS-scores challenges evidence regarding the stability of pain catastrophizing. However, larger studies of psychological risk factors for pain after TKA are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Severe knee osteoarthritis is the most common reason for patients to seek knee replacement. Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) improves function and reduces pain for the majority of patients, and pain relief is likely to be the most important long-term outcome [1]. However, research indicates that persistent pain is a considerable problem, affecting up to 34 % of patients [2–6]. Surgery is a known risk factor for developing chronic pain, most often defined as pain present for at least three months [7]. Studies have found that almost 20 % of patients are not satisfied one year after surgery [2, 4, 8]. The main reason appears to be persistent pain during activities of daily living [5, 9–11].

TKA is considered a painful procedure, and pain after hospital discharge is an ongoing challenge despite multimodal approaches to pain management [12]. Pain after surgery seems to be the main factor limiting early mobilization [13]. Successful rehabilitation after TKA depends on patients’ recovery efforts and ability to cope with pain. Physical activities targeted towards regaining muscle strength are important to reduce the risk of postoperative complications such as prolonged stiffness, persistent pain and diminished function [14–16].

Recent studies evaluating the predictors of persistent pain after TKA have suggested that some psychological variables might predispose individuals to a negative pain-related outcome after surgery [10, 17]. Anxiety and depression have been frequently evaluated, and the role of pain catastrophizing is increasingly being considered [18, 19]. Pain catastrophizing is characterized by the tendency to magnify the threat from pain stimulus, to feel helpless in the context of pain and to ruminate about the pain experience [20]. Catastrophizing in a pain context can reduce the patient’s adherence to the training program and appears to have a negative impact on pain severity after TKA [21]. Preoperative pain catastrophizing has been a strong predictor of postoperative pain in several studies of knee replacement surgery [21–24]. However, other studies find weak or no association [25, 26] and a recent systematic review found that only a few studies have followed patients beyond three months [18].

The primary aim of this study was to explore the association between preoperative pain catastrophizing and postoperative pain up to one year after surgery in patients undergoing primary TKA. Second, we wanted to investigate a possible shift in postoperative pain catastrophizing.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was conducted at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at St. Olavs University Hospital in Trondheim, Norway between January and June 2013. Baseline questionnaires of pain and pain catastrophizing were given to the patients for self-administration at the pre-surgical evaluation, within two weeks prior to surgery and the follow-up assessment of pain two days after surgery, when hospitalized. Further follow-up was performed at two weeks, eight weeks and one year after surgery. The participants were sent one postal reminder after two weeks if the questionnaires were not returned. Those who did not respond were considered non-responders.

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Central Norway (no. 2012/1698/REK midt). The patients received oral and written information about the study, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before inclusion.

Patient population

The patients followed a standardized fast-track procedure for hip and knee arthroplasty implemented in our department [27]. All patients scheduled for primary TKA were consecutively included after approving participation. The first author was responsible for patient inclusion and administration of the follow-up questionnaires. Criteria for exclusion were: lack of ability to write or read Norwegian, cognitive impairments (inability to provide informed consent) or refusal to participate.

Measures

Pain was measured by the Norwegian version of the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) Short form [28]. The BPI is a short, self-administered questionnaire designed to assess the intensity of pain and the impact of pain on daily function during the past 24 h [29–32]. The BPI consists of eleven items, of which four questions are related to pain intensity; pain now, worst, least and average pain. The patients are asked to rate their pain on a numerical rating scale (NRS), where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst imaginable pain. The primary outcome was the item “average pain” measured at two days, two weeks, eight weeks and one year follow-up.

Pain catastrophizing was measured by the Norwegian version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [33, 34]. The PCS consists of thirteen items describing the thoughts and feelings that patients may experience when they are in pain [20]. Patients rate their thoughts regarding pain using a five-point Likert scale with the endpoints 0 (“not at all”) and 4 (“all the time”). It is self-administered and the PCS total score is calculated by summing the thirteen- item responses ranging from 0 (no catastrophizing) to 52 (severe catastrophizing). PCS is considered to have high internal consistency with Chronbach’s α reported to be 0.87 [34]. Individuals who score above 30 on the PCS are considered to be at high risk for developing chronicity and considered suitable candidates for risk-factor targeted intervention programs [20]. Pain catastrophizing was measured at baseline, at eight weeks- and one year follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21. Visual inspections of Q-Q plots were used to determine whether or not the data were normally distributed.

The preoperative PCS scores were not normally distributed and are therefore presented as medians (with quartiles). Preoperative pain scores were normally distributed and are presented as means (SD). The Mann–Whitney U-test was used when comparing preoperative PCS scores and independent samples Student’s t-test when comparing preoperative pain between the genders. Average pain and PCS scores at the follow-up assessments were analyzed using mixed linear models to account for dependency caused by repeated measures data. All baseline characteristics presented in Table 1 were initially considered as potential covariates. Preoperative pain score and gender were used as covariates in the model based on the result from directed acyclic graphs analyses [35]. The residuals in the model were found to be normally distributed. Bonferroni adjustment was used when comparing differences in average pain between the different follow-up assessments. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.050.

Results

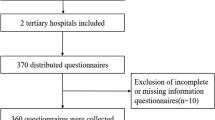

Seventy-one of 89 patients undergoing TKA during the period were included in the present study (80 %). Fig. 1 shows the flow of patients through the study. Baseline and demographic data are presented in Table 1.

The overall median preoperative PCS score was 17.0 (7.8–28.3). The median for females was 17.5 (8.0–27.8) and that for males 17.0 (6.8–32.0). The difference between the sexes was not statistically significant (p =0.865). The overall model estimated PCS mean score was 7.6 at eight weeks and 6.5 at one year follow-up. There was no statistical significance between the results at eight weeks and one year follow-up (p = 0.290); however both the results at eight weeks and one year follow-up were significantly lower than the preoperative value (p < 0.001).

The mean preoperative average pain score was 5.4 (2.2). The females mean score was 6.1 (2.0) and males 4.7 (2.2) with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.006). There were statistically significant differences in the pain scores across the follow-up assessments (p < 0.001). Differences between results of the follow-up assessments are presented in Table 2.

The model adjusted, preoperative PCS score had no statistically significant effect on the postoperative pain score (p = 0.942). Females reported a mean postoperative pain score of 3.5 and males reported 3.1 (p = 0.323).

Preoperative pain was a significant covariate in the mixed linear model (p < 0.001). An increase of 1 in preoperative pain score resulted in an increase of 0.4 in postoperative pain score.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to examine whether the levels of preoperative pain catastrophizing were associated with pain up to one year after TKA. We found no support for such an association. The preoperative catastrophizing had no significant influence on postoperative pain at any of the follow-up assessments.

The PCS is thought to be useful for identifying individuals predisposed to a heightened distress response to painful procedures such as surgery [34]. Recognizing risk factors for acute or persistent pain after knee replacement could allow targeted perioperative treatment, including tailored postoperative pain treatment or individualized postoperative follow-up. Several studies report catastrophizing to be highly correlated with pain related outcomes [17] and pain catastrophizing is frequently mentioned as a contributor to acute and persistent pain after TKA [21–23, 36]. Our results do not support the PCS questionnaire as a tool to identify patients at risk for developing persistent pain after TKA.

Wether the PCS has a predictive value for postoperative pain seems inconclusive [18]. Other studies of TKA [24, 37, 38], as well as other types of surgery [39, 40], are in accordance with our results and have found little or no evidence for an association between pain catastrophizing and postsurgical pain. A prospective cohort study by Banka et al. (2015) even found that high catastrophizing gave decreased odds of postoperative opioid use six weeks after TKA, and found no evidence of an association between preoperative catastrophizing and postoperative pain [25].

Our secondary aim was to investigate a possible shift in pain catastrophizing after surgery. Interestingly, we found a significant reduction in catastrophizing during the follow-up period. The levels of preoperative catastrophizing were relatively high in the present study. Comparable studies of TKA report a wide variety of preoperative PCS scores with mean values from 7.1 to 19.4 [11, 21, 41–43]. High scores of preoperative catastrophizing in our study may be explained by imminent surgery, considering that catastrophizing is related to the tendency to exaggerate the possibility of a catastrophic result [44] as well as the level of preoperative pain. Knee joint arthritis is defined as chronic pain [45] and psychologically robust individuals may have the tendency to catastrophize when experiencing pain in certain situations [41, 44]. Joint replacement is considered a highly effective treatment for reducing pain in patients diagnosed with osteoarthritis [1]. When pain intensity declined, so did the levels of catastrophizing. However, a recent systematic review of patients undergoing TKA, found that pain catastrophizing levels remain stable over time [4]. This could have been caused by differences in research methods, but many studies lack a thorough description of the organization of the patient pathway (patient education, length of stay, physiotherapy follow-up etc.) which may have influenced pain catastrophizing scores.

Reducing pain catastrophizing is highlighted as a key factor in determining successful rehabilitation for pain-related conditions [46] and reduction of catastrophizing is associated with clinical improvement of pain [47]. Catastrophizing shows some degree of stability over time in the absence of interventions but can be context dependent and determined by situational factors [48]. Several intervention studies have examined the possibility of modifying catastrophizing. Psychological and psychosocial interventions [49], education and instruction in self-management skills [50] or exercise and physical therapy [51, 52] were shown to be effective in reducing pain catastrophizing to some degree.

The consequence of pain-related psychosocial risk factors such as pain catastrophizing, seems to be reduced activity or participation in daily activities. Providing assurance that the pain condition does not contain a serious health risk has shown to have an effect on physical activity [53]. Information and education allow patients to re-evaluate the threat they associate with their condition [54]. In our study there were no interventions aimed at reducing catastrophizing. However, all patients in the fast-track program are given the best evidence-based treatment available, targeting patient education, pain relief and early mobilization, which reduces the need for hospitalization [55]. This includes a preoperative educational class and individual information (oral and written) on specific clinical procedures. Our fast-track pathway encourages and educates patients to cope at home, they have the ability to contact the hospital after discharge and they receive several hours of physical therapy during the postoperative course. All baseline questionnaires were administered before the patient information and educational class, thereby including a possible effect of education in the reduction of PCS. Together with pain reduction, these factors may have been important for the reduction of pain catastrophizing in our study. Our findings suggest the need for further research regarding possible positive effects of the fast-track program.

As to be expected, the level of pain decreased over time, confirming TKA as an effective treatment for knee arthrosis [6, 27]. A higher level of preoperative pain was associated with higher postoperative pain in our study. These findings are in accordance with previous published research across different surgical fields [56]. Preoperative pain is a well-known predictor of acute and persistent postoperative pain, according to several studies [19, 57, 58].

Regarding gender, most TKAs are performed in women [59] and studies show that women are at greater risk of developing osteoarthrosis in the knee, especially after the menopause [60]. In recent years, clinical and epidemiological research has demonstrated gender differences in pain experience. Females seem to have an increased risk of persistent pain and they experience more severe clinical pain [61]. However, the results are inconclusive. Lingard et al. [62] showed that female gender had no influence on pain after TKA when adjusting for preoperative status but females had more pain at the preoperative assessment. This is in accordance with our results. When adjusting for preoperative pain, female gender was no longer statistically significant.

The study findings must be interpreted with consideration of some study limitations. First, we cannot rule out that completing the PCS questionnaire at the outpatient clinic shortly before surgery may have biased the level of catastrophizing. Second, the study cohort of 71 patients was small, but seems representative for patients scheduled for TKA as 80 % of all patients undergoing TKA during the study period were included. The sample size was comparable to other similar studies [21, 23, 36] and the response rate at each follow-up was very good. Including measures of anxiety and depression may have strengthened our study further.

Conclusions

We found no association between preoperative catastrophizing and persistent postoperative pain in TKA patients up to one year after surgery. This may question the use of PCS as a preoperative tool to identify patients at risk for persistent pain after TKA. Further, the large reduction in pain catastrophizing scores from baseline to follow-up, both at eight weeks and one year, challenges the evidence concerning stability of pain catastrophizing over time.

Ethics approval

As stated in the Methods section, all participants signed a written informed consent. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Central Norway (no. 2012/1698/REK midt).

Consents for publications

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Request for details in the study dataset can be submitted to the corresponding author. Human subject protection requirements, appropriate data privacy as well as institutional requirements must be met.

Abbreviations

- ASA:

-

American society of anesthesiology classification

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BPI:

-

brief pain inventory

- NRS:

-

numerical rating scale

- PCS:

-

pain catastrophizing scale

- TKA:

-

total knee arthroplasty

References

Murray DW, Frost SJ. Pain in the assessment of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80(3):426–31.

Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J, Gregg PJ. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement. Data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89(7):893–900. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19091.

Brander VA, Stulberg SD, Adams AD, Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanos SP, et al. Predicting total knee replacement pain: a prospective, observational study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;416:27–36. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000092983.12414.e9.

Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000435. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435.

Puolakka PA, Rorarius MG, Roviola M, Puolakka TJ, Nordhausen K, Lindgren L. Persistent pain following knee arthroplasty. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27(5):455–60. doi:10.1097/EJA.0b013e328335b31c.

Wylde V, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Persistent pain after joint replacement: prevalence, sensory qualities, and postoperative determinants. Pain. 2011;152(3):566–72. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.023.

Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. 2. ed. Seattle: IASP press; 1994.

Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57–63. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9.

Scott CE, Howie CR, MacDonald D, Biant LC. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a prospective study of 1217 patients. J Bone Joint Surg. 2010;92(9):1253–8. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.24394.

Bonnin MP, Basiglini L, Archbold HA. What are the factors of residual pain after uncomplicated TKA? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1411–7. doi:10.1007/s00167-011-1549-2.

Sullivan M, Tanzer M, Reardon G, Amirault D, Dunbar M, Stanish W. The role of presurgical expectancies in predicting pain and function one year following total knee arthroplasty. Pain. 2011;152(10):2287–93. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.014.

Aasvang EK, Luna IE, Kehlet H. Challenges in postdischarge function and recovery: the case of fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2015. doi:10.1093/bja/aev257.

Andersen LO, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen BB, Husted H, Otte KS, Kehlet H. Subacute pain and function after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(5):508–13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05831.x.

Saleh KJ, Lee LW, Gandhi R, Ingersoll CD, Mahomed NN, Sheibani-Rad S, et al. Quadriceps strength in relation to total knee arthroplasty outcomes. Instr Course Lect. 2010;59:119–30.

Greene KA, Schurman 2nd JR. Quadriceps muscle function in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(7 Suppl):15–9. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2008.06.014.

Scuderi GR. The stiff total knee arthroplasty: causality and solution. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(4 Suppl 2):23–6.

Theunissen M, Peters ML, Bruce J, Gramke HF, Marcus MA. Preoperative anxiety and catastrophizing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with chronic postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(9):819–41. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31824549d6.

Burns LC, Ritvo SE, Ferguson MK, Clarke H, Seltzer Z, Katz J. Pain catastrophizing as a risk factor for chronic pain after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Pain Res. 2015;8:21–32. doi:10.2147/JPR.S64730.

Lewis GN, Rice DA, McNair PJ, Kluger M. Predictors of persistent pain after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(4):551–61. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu441.

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale. User Manual 2009. Available from: http://sullivan-painresearch.mcgill.ca/pcs1.php. Accessed: 11.13.2015.

Sullivan M, Tanzer M, Stanish W, Fallaha M, Keefe FJ, Simmonds M, et al. Psychological determinants of problematic outcomes following Total Knee Arthroplasty. Pain. 2009;143(1–2):123–9. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.011.

Riddle DL, Wade JB, Jiranek WA, Kong X. Preoperative pain catastrophizing predicts pain outcome after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(3):798–806. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0963-y.

Forsythe ME, Dunbar MJ, Hennigar AW, Sullivan MJ, Gross M. Prospective relation between catastrophizing and residual pain following knee arthroplasty: two-year follow-up. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13(4):335–41.

Noiseux NO, Callaghan JJ, Clark CR, Zimmerman MB, Sluka KA, Rakel BA. Preoperative predictors of pain following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(7):1383–7. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.034.

Banka TR, Ruel A, Fields K, YaDeau J, Westrich G. Preoperative predictors of postoperative opioid usage, pain scores, and referral to a pain management service in total knee arthroplasty. HSS J. 2015;11(1):71–5. doi:10.1007/s11420-014-9418-4.

Brummett CM, Urquhart AG, Hassett AL, Tsodikov A, Hallstrom BR, Wood NI, et al. Characteristics of fibromyalgia independently predict poorer long-term analgesic outcomes following total knee and hip arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(5):1386–94. doi:10.1002/art.39051.

Winther SB, Foss OA, Wik TS, Davis SP, Engdal M, Jessen V, et al. 1-year follow-up of 920 hip and knee arthroplasty patients after implementing fast-track. Acta Orthop. 2015;86(1):78–85. doi:10.3109/17453674.2014.957089.

Klepstad P, Loge JH, Borchgrevink PC, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS, Kaasa S. The Norwegian brief pain inventory questionnaire: translation and validation in cancer pain patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(5):517–25.

Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2004;5(2):133–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005.

Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(1):17–24. doi:10.1093/bja/aen103.

Gjeilo KH, Klepstad P, Wahba A, Lydersen S, Stenseth R. Chronic pain after cardiac surgery: a prospective study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54(1):70–8. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02097.x.

Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105–21. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005.

Fernandes L, Storheim K, Lochting I, Grotle M. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Norwegian pain catastrophizing scale in patients with low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:111. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-111.

Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–32. doi:10.1037//1040-3590.7.4.524.

Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:70. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-70.

Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT, Klick B, Katz JN. Catastrophizing and depressive symptoms as prospective predictors of outcomes following total knee replacement. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14(4):307–11.

Masselin-Dubois A, Attal N, Fletcher D, Jayr C, Albi A, Fermanian J, et al. Are psychological predictors of chronic postsurgical pain dependent on the surgical model? A comparison of total knee arthroplasty and breast surgery for cancer. J Pain. 2013;14(8):854–64. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2013.02.013.

Rakel BA, Blodgett NP, Bridget Zimmerman M, Logsden-Sackett N, Clark C, Noiseux N, et al. Predictors of postoperative movement and resting pain following total knee replacement. Pain. 2012;153(11):2192–203. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2012.06.021.

Peters ML, Sommer M, de Rijke JM, Kessels F, Heineman E, Patijn J, et al. Somatic and psychologic predictors of long-term unfavorable outcome after surgical intervention. Ann Surg. 2007;245(3):487–94. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000245495.79781.65.

Grosen K, Vase L, Pilegaard HK, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Drewes AM. Conditioned pain modulation and situational pain catastrophizing as preoperative predictors of pain following chest wall surgery: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(2), e90185. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090185.

Wade JB, Riddle DL, Price DD, Dumenci L. Role of pain catastrophizing during pain processing in a cohort of patients with chronic and severe arthritic knee pain. Pain. 2011;152(2):314–9. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.034.

Roth ML, Tripp DA, Harrison MH, Sullivan M, Carson P. Demographic and psychosocial predictors of acute perioperative pain for total knee arthroplasty. Pain Res Manag. 2007;12(3):185–94.

Feldman CH, Dong Y, Katz JN, Donnell-Fink LA, Losina E. Association between socioeconomic status and pain, function and pain catastrophizing at presentation for total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:18. doi:10.1186/s12891-015-0475-8.

Turner JA, Aaron LA. Pain-related catastrophizing: what is it? Clin J Pain. 2001;17(1):65–71.

Classification of Chronic Pain. IASP Taxonomy. 2012. Available from: http://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673&navItemNumber=677. Accessed: 08.29.15

Alschuler KN, Molton IR, Jensen MP, Riddle DL. Prognostic value of coping strategies in a community-based sample of persons with chronic symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Pain. 2013;154(12):2775–81. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.08.012.

Domenech J, Sanchis-Alfonso V, Espejo B. Changes in catastrophizing and kinesiophobia are predictive of changes in disability and pain after treatment in patients with anterior knee pain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(10):2295–300. doi:10.1007/s00167-014-2968-7.

Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(1):52–64.

Sullivan MJ, Adams H, Rhodenizer T, Stanish WD. A psychosocial risk factor--targeted intervention for the prevention of chronic pain and disability following whiplash injury. Phys Ther. 2006;86(1):8–18.

Moseley GL, Nicholas MK, Hodges PW. A randomized controlled trial of intensive neurophysiology education in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(5):324–30.

Smeets RJ, Vlaeyen JW, Kester AD, Knottnerus JA. Reduction of pain catastrophizing mediates the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2006;7(4):261–71. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2005.10.011.

Slepian P, Bernier E, Scott W, Niederstrasser NG, Wideman T, Sullivan M. Changes in pain catastrophizing following physical therapy for musculoskeletal injury: the influence of depressive and post-traumatic stress symptoms. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(1):22–31. doi:10.1007/s10926-013-9432-2.

Wideman TH, Sullivan MJ. Reducing catastrophic thinking associated with pain. Pain Manag. 2011;1(3):249–56. doi:10.2217/pmt.11.14.

Moseley GL. Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(1):39–45. doi:10.1016/S1090-3801(03)00063-6.

Kehlet H, Thienpont E. Fast-track knee arthroplasty - status and future challenges. Knee. 2013;20 Suppl 1:S29–33. doi:10.1016/S0968-0160(13)70006-1.

Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367(9522):1618–25. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68700-X.

Kalkman CJ, Visser K, Moen J, Bonsel GJ, Grobbee DE, Moons KG. Preoperative prediction of severe postoperative pain. Pain. 2003;105(3):415–23.

Singh JA, Gabriel S, Lewallen D. The impact of gender, age, and preoperative pain severity on pain after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(11):2717–23. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0399-9.

Ritter MA, Wing JT, Berend ME, Davis KE, Meding JB. The clinical effect of gender on outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(3):331–6. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2007.10.031.

Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, Winzenberg TM, Hosmer D, Jones G. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(9):769–81. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.014.

Bartley EJ, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):52–8. doi:10.1093/bja/aet127.

Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright EA, Sledge CB, Kinemax OG. Predicting the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(10):2179–86.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funding was obtained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All the authors contributed to the literature search, data analysis, and interpretation. LHH, KHG and SBW contributed to the study design, and LHH was responsible for data collection. OAF conducted the data analysis. All the authors contributed substantially to drafting of the article and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Høvik, L.H., Winther, S.B., Foss, O.A. et al. Preoperative pain catastrophizing and postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study with one year follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17, 214 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1073-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1073-0