Abstract

Background

Data are currently insufficient to support the use of adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) after surgical resection for stage II or III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in patients aged ≥ 75 years. In this study we evaluated efficacy and safety profile of ACT in this population.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated 140 patients ≥ 75 years who underwent curative surgical resection for stage II–III NSCLC from 2010 to 2018 with an indication to ACT according to current guidelines. A propensity score-matched analysis was performed to avoid cofounding biases.

Results

Thirty of 140 patients (21%) received ACT. Most patients (n = 24, 80%) received carboplatin in combination with vinorelbine, while 5 patients (17%) received cisplatin plus vinorelbine and one patient (3%) carboplatin plus gemcitabine. The occurrence of adverse events led to treatment discontinuation in 8 (27%) cases, while 19 (63%) patients completed 4 chemotherapy cycles. Common reported adverse events with ACT were anemia (n = 20, 67%), neutropenia (n = 18, 60%), thrombocytopenia (n = 9, 30%), renal impairment (n = 4, 13%) and transaminase elevation (n = 4, 13%). No toxic deaths occurred. The median follow-up was 67 months (IQR: 53–87). ACT was associated with a significant benefit in both relapse-free survival (median 36 vs. 18.5 months, p = 0.049) and overall survival (median not reached [NR] vs. 33.5 months, p = 0.023) in a propensity score-matched analysis which controlled for cofounders.

Conclusion

ACT confers a survival benefit after curative resection of stage II–III NSCLC in selected patients aged 75 years or older with a manageable toxicity profile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer, the leading cause of death from cancer worldwide, is a disease of older adults [1]: the median age at the diagnosis is 70 years and approximately 37% of the patients are older than 75 years [2]. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients diagnosed with stage I to IIIA disease are eligible for surgical resection with curative intent. However, 35% of these patients die because of local or metastatic tumor recurrence, which occurs in 65–75% of the patients [3].

The eighth edition of the TNM lung cancer staging system proposed by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) [4] is currently used. Discrepancies exist between the 7th TNM staging system and 8th TNM staging system: node-negative tumors > 4 cm but ≤ 5 cm have been classified as stage IIA instead of stage IB in 8th TNM staging system and the classification of T3 and T4 tumors has changed, as well as those of stage III subgroups. For this reason, many results from previous studies may not be directly translated into current clinical practice.

Surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II–IIIA NSCLC represents the standard of care. Several phase III randomized controlled trials demonstrated the associated survival benefit [5,6,7], corresponding to a 5-year absolute overall survival (OS) benefit of 5.4% [8]. Despite the advent of immune-oncology and tyrosine-kinase inhibitors in the treatment of advanced and locally advanced NSCLC, the standard of care in the adjuvant setting is still platinum-based chemotherapy in the vast majority of cases. Only very recently osimertinib has been approved in the adjuvant setting in patients with stage IB-IIIA NSCLC harboring EGFR exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R substitution mutations [9].

The Lung Adjuvant Cisplatin Evaluation (LACE) pooled analysis showed a negative effect on survival outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage IA, while the risk reduction for death was 8% for stage IB [8]. Other studies have shown no clear survival advantage for adjuvant chemotherapy among patients operated for stage IB NSCLC, while a subgroup analysis from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 9633 trial reported a statistically significant survival benefit with adjuvant chemotherapy for tumors ≥ 4 cm [10] (stage II in the TNM 8th edition). For these reasons adjuvant chemotherapy has been debated for patients with stage IB tumors, while it has been considered as standard of care for tumors ≥ 4 cm [11] and most of the trials have included patients with stage IB ≥ 4 (stage II in the TNM 8th edition) cm in addition to stage II and IIIA.

On the other hand, optimal management of patients with stage III disease remains challenging in the context of highly heterogeneous disease characteristics that require multidisciplinary approaches.

There is a lack of evidence regarding adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients, which translates into the absence of clear guidelines for the use of adjuvant treatment in this population. This is due to the lack of large prospective studies specifically testing adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients and the absence of a representative population in main clinical trials: only the 9% of patients in a meta-analysis of randomized trials were older than 70 years [12]. Our knowledge is limited to retrospective studies of population databases and post hoc analyses of prospective studies.

However, despite the utilization of dosage adjustments, the lower dose intensity and the use of carboplatin instead of cisplatin, the elderly population has been shown to experience survival benefit from adjuvant treatment [13, 14]. Moreover, no differences in severe toxicity rates were found when patients over 65 years old were compared to younger patients in a LACE pooled analysis [12]. However, the survival benefit was limited to patients aged less than 80 for stage II–IIIA [15] and to patients aged less than 75 for stage IB ≥ 4 cm [3], although these findings should be considered with caution since they originate from post hoc analyses with small sample sizes, and adjuvant chemotherapy is not recommended for patients ≥ 75 years old in the guidelines [11].

In spite of the reported survival gain, the similar tolerability to those of younger patients and the possibility to use carboplatin without a survival disadvantage [15], adjuvant chemotherapy is still not offered to the vast majority of older adults, mostly due to the lack of a proven benefit.

The purpose of this retrospective study was to identify the role of adjuvant chemotherapy and to collect real-world data on toxicity rates, dose adjustments and dose intensity in patients aged 75 years or older that underwent curative surgical resection for NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Patient cohort

We conducted a monocentric, retrospective review of patients aged 75 years or older that underwent curative surgical resection for stage II–IIIA NSCLC in accordance with the 8th edition of the TNM classification at the Thoraxklinik Heidelberg from 2010 to 2018. Although T3N2M0 and T4N2M0 tumors have been reclassified to stage IIIB in the 8th edition of the IASLC staging system, these patients remain eligible (as stage IIIA under the 7th edition criteria). Patients with performance status (PS) according to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) ≤ 1, R0 surgery, glomerular filtration rate ≥ 45 ml/min and survival from the surgical intervention of at least 30 days were included.

We retrospectively collected clinicopathological features such as gender, age at the time of surgery, comorbidities, PS ECOG, renal function at the time of surgery, histology, tumor (T) and nodal (N) status, stage of the tumor, chemotherapy dosing and dose adjustments and discontinuations. Adverse events were recorded after every cycle of chemotherapy and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (CTCAE 5.0). Comorbidities were summarized using Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). We did not include lung cancer as a comorbidity in the scores’ calculation. We also reviewed follow-up data of tumor recurrence and death.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize patients’ characteristics and toxicity profile. Results are presented as absolute numbers and percentages and median (minimum [min.]–maximum [max.]), where appropriate. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables between observation and chemotherapy group. Between-group comparisons of continuous variables were performed with Mann–Whitney test.

Univariate logistic regression was used to (retrospectively) identify factors associated with the treating physician’s choice to administer adjuvant chemotherapy or not (binary dependent variable). Gender, age, T status, N status, stage of the tumor, PS ECOG, CCI were considered as independent variables. Results are reported as Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

We performed a 1:1 propensity score matching to compare patients based on adjuvant chemotherapy receipt. The matching was done based on age, stage and N-status. We matched 30 patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy with one patient each from the observation group based on the above-mentioned matching criteria. Survival analysis were performed on the propensity-matched sample.

The relapse-free survival period (RFS) was defined as the time from the date of the surgery to the date of recurrence or death or to the last date in which the patient was known to be disease-free. The overall survival (OS) period was defined as the time from the date of the surgery to the day of death or the last date in which the patient was known to be alive. RFS and OS were assessed using the Kaplan–Meier method and the differences between the curves were tested using the two-tailed log-rank test.

As sensitivity analysis, univariable and multivariable Cox regression hazard models were applied to the entire (unmatched) population including all potentially relevant clinical variables, like post-surgical treatment (observation/adjuvant chemotherapy), age group (< 80/ ≥ 80), sex, ECOG score, CCI (0–1/ ≥ 2), histology, smoking history, N-stage, T-stage, type of surgical operation (lobar resection/sub-lobar resection/pneumonectomy) and pathologic stage, in order to identify parameters significantly associated with RFS and OS. Variables with p < 0.2 in the univariable testing were subsequently included in the multivariable analysis.

We considered a p-value < 0.05 as statistically significant. All data were analyzed using R version 3.6.2 statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the “survival” (v.3.2–13) and the “MatchIt” packages (v. 4.2.0).

Results

Patients´ demographics

Between 2010 and 2018, 259 patients aged 75 years or older underwent surgical resection for lung cancer in our center. We identified 204 patients that underwent surgical resection for early-stage NSCLC with a formal indication to adjuvant chemotherapy according to the guidelines. Of these, 64 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria.

The majority of patients were men (59%) and the median age was 78 years (min.–max.: 75–91).

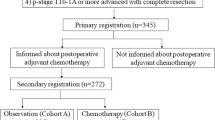

Among the 140 included patients, only 30 patients (21%) received adjuvant chemotherapy (Fig. 1). Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that factors significantly associated with receiving adjuvant chemotherapy after curative surgery were age (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.48–0.79, p < 0.001), N status (OR 2.68, 95% CI 1.53–4.94, p < 0.001) and stage (OR 6.96, 95% CI 2.29–30.39, p = 0.002), while T status, gender, PS ECOG, CCI were not significantly associated with the administration of adjuvant treatment. Patients’ characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Chemotherapy dosing, discontinuation rates and toxicity

Among patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, 24 (80%) received carboplatin in association with vinorelbine, 5 (17%) cisplatin in association with vinorelbine and one (3%) carboplatin in association with gemcitabine. In total, 8 patients (27%) required treatment discontinuation due to toxicity, while most of the patients (n = 19, 63%) completed all four planned cycles of chemotherapy.

Information on chemotherapy dosage and cycles delays in one patient was missing. Fourteen patients (47%) required dose reduction, 7 patients (23%) from the first cycle and the remaining patients due to the occurrence of toxicity. In 14 patients (47%) chemotherapy was postponed once or more often because of adverse events. Four patients receiving cisplatin required delays of the treatment and three of them required discontinuation for intolerable adverse events.

Information on specific toxicity in four patients was missing. Common reported adverse events were anemia (n = 20, 67%), which reached grade 3 in two cases (7%), and neutropenia (18 patients, 60%), that reached grade 3 in 9 (50%) cases. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factors were administered in 9 patients (30%), 5 patients (17%) experienced febrile neutropenia. Other frequent reported adverse events were thrombocytopenia (n = 9, 30%), renal impairment (n = 4, 13%) and transaminase elevation (n = 4, 13%). No toxicity-related deaths were reported. Chemotherapy regimens and toxicity profile are summarized in Table 2.

Survival analysis

A total of 30 propensity-matched pairs—one each from the adjuvant chemotherapy and the observation group—were included for this analysis. The groups did not differ significantly in baseline characteristics (Table 1). The median follow-up was 67 months (interquartile range [IQR] 53–87).

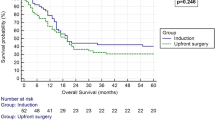

The median RFS was 36 months in the chemotherapy group and 18.5 months in the observation group (HR 0.54 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.28–1], p = 0.049). The 5-year RFS was 46% and 17% in the chemotherapy and the observation group, respectively (p = 0.049).

The median OS was not reached (NR) in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, while it was 33.5 months in patients in the observation group (HR 0.45 [95% CI 0.22–0.92], p = 0.023). The 5-year OS was 61% for the chemotherapy group and 39% for the observation group (p = 0.046).

The Kaplan–Meier curves are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

The univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, which were performed for the entire (unmatched) population as sensitivity analyses, are provided as supplementary material (Additional file 1). In the multivariable analysis, adjuvant chemotherapy was identified as an independent and significant factor for RFS (HR 0.49 [95% CI 0.28–0.87], p = 0.015) and OS (HR 0.43 [95% CI 0.22–0.82], p = 0.010) along with ECOG PS (RFS HR 1.66 [95% CI 1.09–2.55], p = 0.020; OS HR 1.84 [95% CI 1.15–2.95], p = 0.011), while pathological stage and nodal status did not show significant results.

Discussion

In this study we retrospectively evaluated the safety and efficacy profile of adjuvant chemotherapy in selected patients aged 75 years or older that underwent surgical resection for stage II–III NSCLC.

Among patients treated with surgery with curative intent, we selected those eligible for adjuvant chemotherapy for our retrospective analysis. We excluded patients with PS ECOG higher or equal to 2 and moderate to severe renal impairment and those who underwent R1 or R2 surgery or who died within 30 days from surgery. Only 30 of the 140 eligible patients received adjuvant treatment. Factors associated with receiving this treatment modality were younger age, nodal status and stage, while T stage and CCI did not influence the clinicians’ decision. As reported by others, older patients receive adjuvant chemotehrapy less often than younger patients, in spite of a similar survival benefit [16]. Moreover, the role of PS [17] as well as nodal status [18] as important factors influencing the treatment decision in patients with resectable NSCLC is well known.

Despite accumulating evidence that older patients, even receiving a lower total chemotherapy dose, benefit from adjuvant treatment with acceptable toxicity [19], this treatment modality is still denied to the vast majority of them only on the basis of age and concerns about their ability to tolerate platinum-related toxicity [20]. Indeed, these patients have often an impaired renal and liver function, as well as a reduced hematopoiesis and poor PS. Comorbidities and polipharmacy increase the likelihood to experience inacceptable toxicity [20].

Information on benefit and toxicity risks of adjuvant chemotherapy in the elderly population is lacking, particularly for patients aged 75 years or older, due to the underrepresentation of this age group in randomized controlled trials as a consequence of the selection of participants on the base of comorbidities, functional status and age. No elderly-specific trials of adjuvant chemotherapy in NSCLC have been conducted so far and a specific standardized tool for risk assessment in older patients undergoing adjuvant treatment after surgical resection is still lacking [21]. Only recently the Cancer Aging Research Group (CARG) score, which predicts grade 3–5 chemotherapy toxicity in older adults aged 65 years or older [22], has been validated in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting [23].

A survival benefit for unselected patients aged 65 years or older that received adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II–IIIA NSCLC was demonstrated in an observational cohort study using population-based data. This benefit was, however, not confirmed in patients aged 80 years or older and the administration of platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with an increased risk of toxicity requiring hospital admission. This risk was, however, consistent with those reported in younger patients in previous publications [14]. Moreover, retrospective analyses of controlled trials and pooled analysis evidenced a similar survival benefit for fit older patients compared to younger patients [13, 24].

In our population treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, only four patients (13%) received cisplatin, while the rest of the patients received carboplatin. Treatment discontinuation was required in 27% of the patients, including three patients receiving cisplatin, while dose reductions and cycle delays were required in 43% and 47% of the patients, respectively. With carboplatin and appropriate dose reduction, rates of neutropenia (60%), anemia (67%), febrile neutropenia (17%) and thrombocytopenia (30%) were consistent with those of clinical trials enrolling only patients younger than 75 years old [6] or in which the elderly population represented only a small portion of the enrolled patients [13]. Carboplatin is more commonly used in older patients due to its favorable toxicity profile, with a lower infection and emesis rate. Results from retrospective analyses demonstrated a survival benefit in patients treated with carboplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy over observation, with no significant differences compared to cisplatin-based chemotherapy [15, 25].

In our study cohort, we have found a significant improvement in RFS (median 36 vs 18.5 months) as well as in OS (median NR vs 33.5 months) in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection for stage II–III NSCLC compared to those who did not receive postoperative treatment after propensity score matching. The survival advantage conferred by adjuvant chemotherapy was confirmed in a sensitivity analysis with multivariable Cox regression hazard model which was performed for the entire unmatched population. The benefit conferred by adjuvant chemotherapy in both OS and RFS in patients aged 75 years or older has been reported in other retrospective analyses [26]. The magnitude of the benefit in our cohort is superior to those reported in clinical trials, a discrepancy that can be explained with the high percentage of stage III disease in both populations after propensity-score matching (90% stage III vs. 10% stage II). It is indeed known that stage is a strong predictive factor, with stage III patients benefitting the most from adjuvant chemotherapy [27]. Moreover, our population has a selection bias, in which patients have been carefully evaluated initially for surgical eligibility and in a second time as possible candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy.

Our study has some limitations. The study has a small sample size and is retrospective and not randomized. The decision of whether to use adjuvant chemotherapy was made by the treating physicians, depending on patient’s characteristics, clinical history, and recovery after surgery. Moreover, chemotherapy regimens, dosage adjustments and postponements were not standardized. The use of inclusion criteria and propensity score matching, and the data collected from a single center may however reduce the selection bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study provides further evidence about the benefits in both RFS and OS of adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection of stage II–III NSCLC in highly selected patients aged 75 years or older. Chronological age is not sufficient to determine whether an old patient could benefit from the standard treatment with acceptable toxicity. The evaluation should include the assessment of functional status, comorbidities, surgical sequelae and consider the patient’s preference. Chemotherapy still represents the standard of care in the adjuvant setting, but with the advent of new, more tolerable agents more and more elderly patients will be eligible for adjuvant treatment in the future, a fact that underlines the importance of including this patient population in clinical trials. Prospective randomized trials and larger cohorts are needed to confirm our findings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author, JK, on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Adjuvant chemotherapy

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- IASLC:

-

International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- LACE:

-

Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation

- CALGB:

-

Cancer and Leukemia Group B

- PS:

-

Performance status

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- CTCAE:

-

National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- RFS:

-

Relapse free survival

- NR:

-

Not reached

- CARG:

-

Cancer Aging Research Group

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492.

Torre LA, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Lung cancer statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;893:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24223-1_1.

Malhotra J, Mhango G, Gomez JE, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for elderly patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer ≥4 cm in size: an SEER-Medicare analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:768–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv008.

Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM Classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009.

Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, et al. Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa031644.

Douillard JY, Rosell R, De Lena M, et al. Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70804-X.

Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, et al. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa043623.

Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, et al. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE collaborative group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3552–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9030.

eUpdate – Early and Locally Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer n.d. https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/lung-and-chest-tumours/early-stage-and-locally-advanced-non-metastatic-non-small-cell-lung-cancer/eupdate-early-and-locally-advanced-non-small-cell-lung-cancer-nsclc-treatment-recommendations2. Accessed 13 Sept 2021.

Strauss GM, Herndon JE, Maddaus MA, et al. Adjuvant paclitaxel plus carboplatin compared with observation in stage IB non-small-cell lung cancer: CALGB 9633 with the cancer and leukemia group B, radiation therapy oncology group, and North Central cancer treatment group study groups. J Clin Oncol. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4855.

Postmus PE, Kerr KM, Oudkerk M, et al. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx222.

Früh M, Rolland E, Pignon JP, et al. Pooled analysis of the effect of age on adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy for completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3573–81. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2727.

Pepe C, Hasan B, Winton TL, et al. Adjuvant vinorelbine and cisplatin in elderly patients: National Cancer Institute of Canada and intergroup study JBR. 10. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1553–61. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5570.

Wisnivesky JP, Smith CB, Packer S, et al. Survival and risk of adverse events in older patients receiving postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for resected stages II–IIIA lung cancer: observational cohort study. BMJ. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4013.

Gu F, Strauss GM, Wisnivesky JP. Platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) in elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the SEER-Medicare database: comparison between carboplatin- and cisplatin-based regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2017;29:7014–7014. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.7014.

Rodriguez KA, Guitron J, Hanseman DJ, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy and age-related biases in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.08.075.

Kawaguchi Y, Hanaoka J, Oshio Y, et al. Decrease in performance status after lobectomy mean poor prognosis in elderly lung cancer patients. J Thorac Dis. 2017. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017.04.37.

Goldstraw P, Crowley JJ. The international association for the study of lung cancer international staging project on lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1097/01243894-200605000-00002.

Pallis AG, Gridelli C, Wedding U, et al. Management of elderly patients with NSCLC; updated expert’s opinion paper: EORTC elderly task force, lung cancer group and international society for geriatric oncology. Ann Oncol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu022.

Fervers B. Chemotherapy in elderly patients with resected stage II–IIIA lung cancer. BMJ. 2011;343:d4104–d4104. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4104.

Poudel A, Sinha S, Gajra A. Navigating the challenges of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Drugs Aging. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0350-9.

Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3457–65. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625.

Ostwal V, Ramaswamy A, Bhargava P, et al. Cancer Aging Research Group (CARG) score in older adults undergoing curative intent chemotherapy: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:47376. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047376.

Asmis TR, Ding K, Seymour L, et al. Age and comorbidity as independent prognostic factors in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: a review of National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8322.

Ganti AK, Williams CD, Gajra A, et al. Effect of age on the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29360.

Yamanashi K, Okumura N, Yamamoto Y, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0218492317714669.

Douillard JY, Tribodet H, Aubert D, et al. Adjuvant cisplatin and vinorelbine for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer: Subgroup analysis of the lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:220–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c814e7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, MB, ME and JK; Data curation, MB and JK; Formal analysis, MB and KK; Methodology, MB, PC and JK; Validation, MB and JK; Writing – original draft, MB and JK; Writing – review & editing, all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Heidelberg University Hospital (protocol code S-174/2019). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models for RFS and OS applied on the entire (unmatched) population.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Blasi, M., Eichhorn, M.E., Christopoulos, P. et al. Major clinical benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II–III non-small cell lung cancer patients aged 75 years or older: a propensity score-matched analysis. BMC Pulm Med 22, 255 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-02043-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-02043-6