Abstract

Purpose

This scoping review examines controllable predisposing factors attributable to cancer in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region’s adult population, highlighting opportunities to enhance cancer prevention programs.

Design

We systematically searched the PubMed, Science Direct, and CINAHL, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases from 1997 to 2022 for articles reporting on the impact of modifiable risk factors on adult patients with cancer in the MENA region.

Results

The review identified 42 relevant articles, revealing that tobacco consumption, obesity, physical inactivity, and diet are significant modifiable risk factors for cancer in the region. Tobacco smoking is a leading cause of lung, bladder, squamous cell carcinoma, and colorectal cancer. A shift towards a westernized, calorie-dense diet has been observed, with some evidence suggesting that a Mediterranean diet may be protective against cancer. Obesity is a known risk factor for cancer, particularly breast malignancy, but further research is needed to determine its impact in the MENA region. Physical inactivity has been linked to colorectal cancer, but more studies are required to establish this relationship conclusively. Alcohol consumption, infections, and exposure to environmental carcinogens are additional risk factors, although the literature on these topics is limited.

Conclusion

The review emphasizes the need for further research and the development of targeted cancer prevention strategies in the MENA region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region have experienced rapid growth in their economies, leading to social and cultural changes [1]. As a result, most economies in the Middle East are moving toward a westernized lifestyle associated with a diet rich in calories and limited physical activity. This shift is causing increased rates of obesity and lifestyle-related diseases, most important of which is cancer.

Cancer remains a global universal health problem attributable to reduced life expectancy [2]. In 2020, over 50% of the 20 million reported cancer cases worldwide resulted in death [3]. The burden of cancer is particularly relevant in the Middle East, where more than 430,000 new cancer cases were reported in 2020. Females in the Arab world are more affected by cancer than males, and recent evidence suggests that the elevated prevalence rates of female breast malignancy in the MENA region are due to increased rates of obesity and high consumption of a calorie-dense diet [3,4,5,6].

The literature shows that cancer is largely influenced by lifestyle and environmental factors [7]. In fact, the risk of cancer corresponds to the exposure to carcinogens over time. The major modifiable risk factors, such as smoking, alcohol, high BMI, insufficient physical activity, poor dietary intake, infections, and air pollution, were responsible for 164,780 cancer cases in adults above the age of 30 within the East Mediterranean region [8].

While the noted increase in cancer burden in the MENA region could be attributed to aging, improved diagnosis, and enhanced reporting of cases, the MENA region exhibited a significant increase in the prevalence of modifiable risk factors associated with cancer [9, 10]. Tobacco smoking is the most common substance abuse among adults in the Middle East, with recent studies indicating that 22% of young people aged 13–15 years engage in tobacco smoking [11]. Obesity significantly contributes to the global burden of cancer and disability-adjusted life years (DALY), with the MENA region experiencing a disproportionately high prevalence rate of obesity [4, 12]. Additionally, physical inactivity is prevalent in the MENA region, with recent studies indicating that about 47% of adults and 78% of adolescents do not engage in sufficient physical activity [13, 14].

The aforementioned risk factors were associated with significant increases in the burden of different cancers in the MENA region including but not limited to tracheal, lung, gastrointestinal, urinary, and oral cancers [8,9,10, 15,16,17]. This preventable burden poses a heavy economic strain on countries, especially those developing within the MENA region [18]. Moreover, such a preventable burden might also be hampered by the poor implementation of preventive interventions.

Therefore, this scoping review aims to map the existing evidence in the literature for controllable predisposing factors linked to cancer in the adult population of the MENA region, emphasizing the potential for enhancing cancer prevention programs. The study aims to (1) determine the relationship between cancer and intensity, type, amount, and frequency of tobacco and alcohol consumption; (2) find out if physical activity, diet, and obesity affect cancer in the MENA region; (3) explore the relationship between environmental or occupational exposure and cancer in the MENA region; (4) delineate gaps in the literature linking modifiable risk factors and cancer in the MENA region.

Methods

Evidence acquisition

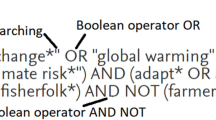

This scoping review investigated the available studies on cancer risk factors, focusing on modifiable predisposing factors in the MENA region. The Arksey and O’Malley framework was used for the scoping review [19]. The research question was tested for eligibility using the PCC (Place, Concept, and Context) framework. In July 2022, a systematic literature search was conducted using the PubMed/MEDLINE, Science Direct, and CINAHL through EBSCOhost, EMBASE, and Cochrane/CENTRAL databases. Furthermore, the records of Google Scholar served as a supplementary resource to ensure a more comprehensive exploration of relevant studies. The search was manually conducted, and keywords were linked with Boolean operators. The results were then filtered by date and relevance. The current review focused on studies published before the year 2022 and after 1997, a period when the countries in the MENA region underwent significant economic, social, and cultural changes.

The search utilized the following keywords in isolation or combination: “Risk factors”, “Modifiable risk factors”, “Cancer”, “Adults, “Youth”, “Middle East”, “Gulf Council Countries”, and “Arab World Countries”. Moreover, the specific names of MENA region countries (e.g., Egypt, Iraq, Yemen, etc…) were incorporated into the search query. Moreover, relevant articles were screened through the bibliographies of relevant secondary researches including all previously published relevant narrative and scoping reviews. All processes, including systematic search conduction and documents, were conducted per the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) statement [20]. The detailed search strategy is illustrated in Supplemental Material A.

Inclusion/exclusion eligibility criteria

Following the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study design) framework, the study’s eligibility criteria included studies reporting on modifiable risk factors linked to cancer among adults in the MENA region between 1997 and 2022. Given the scoping nature of the conducted review, qualitative, quantitative, and mixed study designs were included in the final evidence synthesis.

On the other hand, the study’s exclusion criteria involved studies that failed to fit the conceptual framework developed using the PCC model, articles published in any language other than English, studies conducted outside the MENA region, and studies that presented evidence for childhood cancers or had the study population exclusively below the age of 15 years. This decision aimed to differentiate the study from those concentrating on pediatric oncology, providing a clear delineation of the age groups under consideration. Moreover, certain study types, such as commentaries, conference abstracts, letters to the editors, or editorials, were excluded.

Screening and data extraction

Two authors independently conducted an active search of databases using the eligibility criteria, cross-matching results to identify any discrepancies. All articles were underwent a primary screening process (i.e., by title and abstract) and a secondary screening process (i.e., by full-text content), and any discrepancies within the screening processes were handled by the senior author. The following data was extracted for all eligible articles: (1) study identifier, (2) country of origin, (3) characteristics of study population, (4) study design, (5) outcome measure(s) for predisposing factors attributable to cancer, (6) other relevant results to our study question, and (7) study limitations.

Additionally, data on the following predisposing factors were included: smoking and alcohol consumption, physical activity, diet, obesity, and environmental/occupational exposure. Data on environmental exposure included exposure to pollutants, toxins, or radiation in residential or community settings, living in proximity to industrial areas, waste disposal sites, or other locations where carcinogenic agents are present. Data on occupational exposure included professions that involve contact with substances known or suspected to be associated with an increased risk of cancer, including industrial workers, miners, and those working in carpeting, manufacturing or chemical processing plants.

Due to their relevance, tobacco and alcohol risk factors were examined in terms of intensity, type, and frequency; all of which are defined as follows: (1) intensity of tobacco consumption refers to the strength or concentration of tobacco smoke inhalation, which is measured either in terms of number of daily smoked cigarettes, nicotine content of consumed tobacco products, or smoking pack years. (2) intensity of alcohol consumption signifies the level of alcoholic beverage strength, which is measured in either self-reported drinking habits or standard drinking units. (3) Type of tobacco consumption included cigarettes, cigars, waterpipes (e.g., shisha), or smokeless tobacco products. (4) Type of alcohol consumption included but not limited to beer, wine, and spirits. (5) Frequency of tobacco or alcohol consumption is defined as how often does individuals consume the aforementioned (i.e., daily, weekly, monthly, annually, etc…).

Quality assessment

The JBI critical appraisal tools for cross-sectional, case-control, cohort, and review studies were utilized to assess the quality of included evidence. The aforementioned tools are comprised of 8, 10, 11, and 11 items, respectively.

Results

Included papers

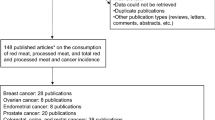

A total of 4495 records were included in the initial screening, and 184 were assessed for eligibility. The search and screening methods in this study identified 42 relevant articles for data extraction (Refer to Fig. 1). Tables 1 and 2 demonstrate the characteristics of included articles. The majority of these studies were from Iran (n = 20), [6, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 followed by Jordan (n = 3), [21,41,42] with Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Lebanon each having two studies [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. Morocco, Syria, Yemen, Tunisia, and Qatar each had one study [51,52,53,54,55]. Figure 2 showcases the geographical distribution of included nations. Included articles were published between 1999 and 2022, with the highest frequency of publications was recorded in 2022 (Refer to Fig. 3). Breast cancer was the most studied cancer (28.6%), followed by head and neck cancers (19.1%) (Refer to Fig. 4).

Most of the studies used a case-control design, with 64.29% being case-control studies, 16.67% being cohort studies, and 14.29% being secondary researches (i.e., narrative reviews, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses) [11, 56,57,58,59,60]. The review found that 22 studies reported tobacco consumption as a predisposing factor for developing cancer, with lung, bladder, squamous cell carcinoma, and colorectal cancer being the most common types of cancer attributable to tobacco consumption in the MENA region (Refer to Fig. 5).

Smoking and cancer in the middle East

Tobacco consumption was the most investigated risk factor predisposing to cancer across the MENA region. For instance, Abdel-Salam et al. (2020) found tobacco smoking status as the leading predictive factor for lung cancer development [51], while Sasco et al. (2002) reported an increased risk of lung cancer through passive smoking [54]. Nasher et al. (2014) found that the consumption of “Shammah” significantly increased the chances of developing oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) [53]. Additionally, Quadri, Tadakamadla, and John (2019) conducted a systematic review and found a strong link between “Shammah” use and the risk of oral cavity cancer [11]. However, the quality of the studies included in this review was low to moderate.

Bedwani et al. (1997) studied the odds ratio of developing bladder cancer in relation to smoking frequency and found that the risk was higher for those who smoked 20 or more cigarettes per day [43]. Zheng et al. (2012) also reported that smokers of 20 packs of cigarettes per day had a five-fold chance of having urothelial carcinoma compared to non-smokers [44]. The study also concluded that passive smoking through environmental exposure increased the risk of developing urothelial carcinoma but did not affect the squamous cell carcinoma type of bladder cancer.

Some studies explored the combined effect of consuming different types of tobacco. Nasrollahzadeh et al. (2008) showed that cigarette smoking alone had a lower adjusted odds ratio (AOR) than hookah smoking alone, but combining the two reduced the AOR even further [30]. However, Zheng et al. (2012) reported that smoking cigarettes alone had a lower odds ratio (OR) for urothelial carcinoma than in combination with waterpipe smoking [44]. Most of the studies that showed tobacco consumption as a predisposing factor for cancer were country-specific, and no study in the review connected tobacco consumption with cancer in Lebanon, despite its high prevalence of smoking.

Diet and cancer in the middle East

Research on diet and cancer in the Middle East has shown that specific diets are linked to cancer development, while others are considered protective. A Mediterranean diet, rich in vegetables, fruits, dairy products, fish, seafood, and coffee and tea, has been found to reduce the likelihood of breast cancer in the region. However, a shift from the Mediterranean to a “westernized diet” of fast foods has been reported in earlier literature. There is a need for further research to determine the effect of combining calorie-dense foods with the Mediterranean diet, especially in countries such as Lebanon, where affordability is a concern.

Azzeh et al. (2022) found that consuming three to five portions of animal products weekly, drinking more than three cups per day of tea, three to five servings per week of fish and seafood, more than three cups of coffee per week, five portions of legumes or more every week, and consuming more than three to five servings of fruits and vegetables per week significantly reduced the likelihood of breast cancer [48]. However, the study only involved post-menopausal women, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations.

Salarabadi, Bidgoli, and Madani (2015) found that increased use of animal oils and reduced consumption of fish oil, milk, yogurt, white meat, soy, and nuts increased the likelihood of breast cancer, whereas a diet composed of lettuce, cabbage, and carrots reduced the risk [32]. Both studies highlighted the importance of encouraging the consumption of the Mediterranean diet in the Middle East.

Hosseini et al. (2022) used the Food Quality Score (FQS) to assess the nutritional quality of different individual types of food and their link with breast cancer risk [27]. The study found an association between compliance with FQS and breast cancer risk among premenopausal women but not among postmenopausal women. Ghoreishy et al. (2021) employed the dietary phytochemical index (DPI) to determine the impact of diet quality on breast malignancy development [6]. The study found that participants with a high DPI had reduced chances of developing breast cancer compared to those with the lowest DPI.

Wang et al. (2021), Shivappa et al. (2017), and Toorang et al. (2021) investigated the effect of diet on the risk of developing other types of cancer besides breast cancer [34, 35, 42]. Toorang et al. (2021) found that increased consumption of sucrose, proteins, and cholesterol increased the chances of developing stomach cancer, while increasing the number of calories from carbohydrates was protective against stomach cancer development [34]. Wang et al. (2021) linked the Dietary Approach Stop Hypertension (DASH)-Fung score with lung cancer risk, showing an inverse relationship [35].

In conclusion, diet affects the development of breast cancer and multiple types of cancer in the Middle East. More studies employing validated diet scores, such as the Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS), Diet Quality Index (DQI), and the Health Eating Index (HEI), are needed to evaluate the effect of diet quality on cancer development in the region.

Obesity and cancer

The Middle East holds an overrepresented position in the global top obesity ranking. Evidence associating being overweight (BMI > 25) and obese (BMI > 30) with cancer development is weak, with five out of 37 studies linking increased BMI to malignancy [24, 33, 45, 47, 57]. Ghiasvand et al. (2012) found that overweight (BMI > 25–29) or obese (BMI > 30) post-menopausal women over 58 years were at higher risk of developing breast malignancy than those with average weight (BMI 18.5–25) [24]. Elkum et al. (2014) studied the impact of obesity on breast malignancy, including women above 18 years, and found that individuals with a BMI greater than 25 were twice as likely to develop breast malignancy than those with a BMI between 20 and 25, for both premenopausal and post-menopausal women [47].

However, the reliability of BMI as a sole parameter for predicting obesity and overweight among women is questionable, with reduced sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing obesity among women [24, 61]. There is a scarcity of studies linking obesity to the risk of developing breast cancer and all types of cancer.

Physical inactivity and cancer

In this review, few studies linked physical inactivity with the risk of developing cancer in the MENA region. Harfouch et al. (2022) identified higher prevalence of colorectal cancer among inactive professions, [55] while Fararouei et al. (2019) showed that vigorous physical activity lowered the chances of breast malignancy in post-menopausal women [23]. Simonian et al. (2018) recorded similar findings, noting that participants without job-related physical activity have higher chances of developing colorectal malignancy [33].

Although Tanner and Cheung (2020) established a relationship between obesity, physical inactivity, and breast malignancy, none of the studies directly linked physical activity to colorectal malignancy [57]. Charafeddine et al. (2017) found that physical activity had less than a 20% protective effect on certain cancers among males, while low physical activity was linked to 21% of gastroesophageal cancer among females in the MENA region [45].

Barriers to physical activity in the Middle East include harsh weather conditions, cultural norms, shortage of sports facilities, poor social support, and motivation (Chaabane et al., 2021) [14]. More studies are needed to increase evidence linking physical inactivity and cancer in this region.

Alcohol consumption and cancer

Although alcohol consumption is relatively low in the MENA region, it remains a common risk factor for cancer development. Studies show increased risks for various cancers among alcohol consumers, such as pancreatic, oropharyngeal, esophageal, liver, and colorectal cancers [45, 46, 49, 62]. Heavy alcohol consumption is more prevalent among men, while women tend to be non-drinkers or occasional drinkers in the region. Alcohol can also increase cancer risk among cigarette smokers, as shown in a study with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma participants [46]. However, some research, such as Nasrollahzadeh et al. (2008), found no connection between alcohol consumption and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [30]. Nonetheless, the study faced limitations due to participants’ illiteracy, which may have underestimated the significance of alcohol exposure as a potential risk factor.

Infections and cancer

A few studies in the MENA region have reported a statistically significant relationship between infections and the risk of cancer. For instance, patients with gastric cancer were more likely to have Helicobacter pylori infections [29]. Schistosomiasis was found to increase the likelihood of developing urothelial and squamous cell carcinoma in both men and women [44]. However, no relationship was found between Epstein-Barr virus, human papillomavirus, and oral squamous cell carcinoma [53]. Similarly, there were no significant difference in the presence of hepatitis G or C among non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients than controls [50]. On the other hand, two Iranian reports reported conflicting results as they demonstrated that there was no difference in hepatitis G genome among non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients versus controls; however, patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma had significantly higher concentrations of hepatitis C and B genomes.

Obeid et al. (2008) conducted a meta-analysis which demonstrated that the HPV prevalence within the MENA region was 16% among the general population, with 54% found among patients with abnormal cervical cytology, and 81% among those with cervical cancer [60].

Exposure to environmental carcinogens

The current review found limited literature on environmental carcinogens as a modifiable risk factor for cancer in the MENA region. One study showed that exposure to high levels of heavy metals, such as nickel and chromium, was linked to increased head and neck malignancy [52]. Another study from Eastern Turkey found high amounts of heavy metals like lead, copper, and cadmium in soil, fruits, and vegetables, suggesting that environmental carcinogens might significantly contribute to cancer pathogenesis, although it remains a modifiable risk factor [63].

Discussion

The current scoping review aimed to find the causal relationship between modifiable risk factors and the likelihood of developing cancer in the MENA region. The WHO states that 30–50% of cancers are preventable through healthy lifestyle choices, and others can be cured if detected early. Modifiable risk factors can be grouped into metabolic, behavioral, and environmental. The Global Burden of Disease (2022) highlights that global cancer mortality rates and disability-adjusted life years (DALY) are attributable to behavioral risk factors such as cigarette smoking, risky sexual behavior, and alcohol consumption [64].

In the MENA region, smoking, alcohol consumption, high BMI, and exposure to environmental carcinogens are the leading modifiable risk factors causing the most significant burden of cancer and DALYs. The most significant portion of lung malignancy in the MENA region directly correlates with the consumption of tobacco products [11, 65, 66]. The WHO (2015) reported that the Middle East experienced a significant increase in tobacco consumption over the past decade, with Lebanon having the highest per capita cigarette smoking rate globally [67]. In fact, Shisha smoking is a social-cultural practice among people in the Arab World and has been consistently linked to lung, bladder, nasopharyngeal, and esophageal cancer [68].

Other reports analyzing data from the Global Burden of Disease datasets of 2019 demonstrated that the incidence and DALYs attributed to various cancers, are on the rise within the MENA region [10, 16, 17]. The most commonly reported risk factors were smoking, high fasting plasma glucose, high BMI, occupational exposure to toxins, and dietary habits. Similar findings were reported in studies examining GLOBOCAN data across the Eastern Mediterranean region or the Gulf Cooperation Council member countries [8, 9]. Across the aforementioned reports, one notion remains consistent; that is, the popularity of smoking and its dominant impact on attributable risk of cancer. The MENA region is currently a rapidly growing market for tobacco consumption [69]. While some nations are trying to implement and cover the WHO’s framework convention on tobacco control and other preventive measures (e.g., quitting clinics, sponsorship bans, taxation among others), the popularity of smoking is increasing multiple folds over the past decade and is even losing its historical ‘taboo’ status among women [9]. Thus, it is only expected for smoking to be the risk factor associated with the highest risk of cancer across the entire region as per the aforementioned published statistics.

However, it should be noted that secondary reports based on either the Global Burden of Disease or GLOBOCAN data might be associated with significant heterogeneity, particularly when it comes to data quality for certain countries. Secondly, most of the published estimates adopt a lax approach when setting assumptions as to simplify their observations (e.g., assuming that risk factors are independent of one another). This issue leads to the inability to assess the joint impact of multiple risk factors or even the confounding effects among them.

To mitigate cancer prevalence in the Middle East, policies should prioritize the reduction of modifiable risk factors. The majority of studies in the current scoping review originated from Iran, indicating a need for more comprehensive research across other countries within the region. Conducting additional studies in diverse nations will contribute to more conclusive findings applicable to the entire MENA region.

Future research should focus on cohort studies, experimental studies using animal models, and more systematic literature reviews. The studies linking predisposing factors to the risk of developing cancer did not have a gender balance as most participants were male. The review mapped many studies showing the association between smoking, high BMI, diet, physical activity, infections, environmental exposure to carcinogens, and the propensity of growing cancer in the Middle East.

The findings justify intensifying efforts to reduce tobacco consumption in the MENA region, such as developing policies that restrict tobacco product consumption. The establishment of physical activity facilities is vital to reduce the number of people at risk of developing obesity, which is a common predisposing factor for breast malignancy. Encouraging the consumption of the Mediterranean diet can also help curb the development of malignancy in this region.

Limitations

The study findings are subject to some limitations. Firstly, all of the included evidence is mainly comprised of observational studies that are associated with poor-to-moderate methodological quality. Secondly, the sample sizes for such types of associations are too limited to provide accurate associations. Thirdly, there is significant heterogeneity among included studies. While some papers provided associations adjusted for a variety of factors, others fail to account for a number of confounders (e.g., type and duration of smoking). Fourthly, diet-related risk factors were mostly generated through questionnaire-based instruments which introduces recall bias; a bias that is augmented over large periods of time. Fifthly, barely any studies provided sufficient details on their sampling strategies; thus, predisposing them to selection bias. Sixthly, among case-controls, the control subjects were sampled from hospital-based settings which may not be reflective of the general targeted populations. Finally, there is a clear underrepresentation of many Middle Eastern nations which makes generalizing any of the synthesized results or conclusions extremely challenging.

Conclusion

The quality and quantity of studies reporting on association between modifiable risk factors and cancer within the MENA region are unsatisfactory. Future efforts should supply the need for prospective cohort and experimental studies that attempt to prove the temporal effects of modifiable risk factors on various types of cancer within a MENA cultural and environmental context. Additionally, policy makers should intensify their efforts in promoting and implementing preventive measures against smoking and other prominent modifiable risk factors. Researchers should strive to examine samples that are representative of their original populations across a variety of settings. Also, underrepresented nations within the MENA region should strive to encourage and produce enough scholarly output for the reliable estimation of the impact of modifiable risk factors on cancer.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Bank.: World Bank Open Data [Internet]. World Bank Open Data, 2022[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://data.worldbank.org.

World Health Organization.: Cancer - Fact Sheet [Internet], 2022[cited 2023 Aug 1] Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries [Internet]. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71:209–249, 2021[cited 2021 Oct 9] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Naja F, Nasreddine L, Awada S et al. Nutrition in the Prevention of Breast Cancer: A Middle Eastern Perspective [Internet]. Frontiers in Public Health 7, 2019[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00316.

Mahdi H, Mula-Hussain L, Ramzi ZS et al. Cancer Burden Among Arab-World Females in 2020: Working Toward Improving Outcomes [Internet]. JCO Global Oncology e2100415, 2022[cited 2022 Jun 13] https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.21.00415.

Ghoreishy SM, Aminianfar A, Benisi-Kohansal S et al. Association between dietary phytochemical index and breast cancer: a case–control study [Internet]. Breast Cancer 28:1283–1291, 2021[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-021-01265-6.

Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Sundaram C, et al. Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes. Pharm Res. 2008;25:2097–116.

Kulhánová I, Znaor A, Shield KD et al. Proportion of cancers attributable to major lifestyle and environmental risk factors in the Eastern Mediterranean region [Internet]. International Journal of Cancer 146:646–656, 2020[cited 2023 Dec 26] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32284.

Al-Zalabani AH. Cancer incidence attributable to tobacco smoking in GCC countries in 2018 [Internet]. Tob Induc Dis 18:18, 2020[cited 2023 Dec 26] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7107909/.

Heidari-Foroozan M, Saeedi Moghaddam S, Keykhaei M, et al. Regional and national burden of leukemia and its attributable burden to risk factors in 21 countries and territories of North Africa and Middle East, 1990–2019: results from the GBD study 2019. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:4149–61.

Quadri MFA, Tadakamadla SK, John T. Smokeless tobacco and oral cancer in the Middle East and North Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. Tob Induc Dis 17, 2019[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: http://www.tobaccoinduceddiseases.org/Smokeless-tobacco-and-oral-cancer-in-the-Middle-East-and-nNorthAfrica-A-systematic,110259,0,2.html.

Seiler A, Chen MA, Brown RL et al. Obesity, Dietary Factors, Nutrition, and Breast Cancer Risk [Internet]. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 10:14–27, 2018[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1007/s12609-018-0264-0.

Chaabane S, Chaabna K, Abraham A et al. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the Middle East and North Africa: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis [Internet]. Sci Rep 10:9363, 2020[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-66163-x.

Chaabane S, Chaabna K, Doraiswamy S et al. Barriers and Facilitators Associated with Physical Activity in the Middle East and North Africa Region: A Systematic Overview [Internet]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18:1647, 2021[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/4/1647.

Al-Zalabani A. Preventability of Colorectal Cancer in Saudi Arabia: Fraction of Cases Attributable to Modifiable Risk Factors in 2015–2040 [Internet]. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:320, 2020[cited 2023 Dec 26] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6981846/.

Nejadghaderi SA, Kolahi A-A, Noori M, et al. The burden of pancreatic cancer and its attributable risk factors in the Middle East and North Africa region, 1990–2019. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;38:1535–45.

Khanmohammadi S, Saeedi Moghaddam S, Azadnajafabad S et al. Burden of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer in North Africa and Middle East countries, 1990 to 2019: Results from the GBD study 2019 [Internet]. Front Oncol 12:1098218, 2023[cited 2023 Dec 26] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9951096/.

Hofmarcher T, Manzano García A, Wilking N et al. The Disease Burden and Economic Burden of Cancer in 9 Countries in the Middle East and Africa [Internet]. Value in Health Regional Issues 37:81–87, 2023[cited 2023 Dec 26] Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212109923000547.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Social Res Methodology: Theory Pract. 2005;8:19–32.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160.

Abdolahinia Z, Pakmanesh H, Mirzaee M, et al. Opium and cigarette smoking are independently Associated with bladder Cancer: the findings of a Matched Case - Control Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021;22:3385–91.

Etemadi A, Khademi H, Kamangar F et al. Hazards of cigarettes, smokeless tobacco and waterpipe in a Middle Eastern Population: a Cohort Study of 50 000 individuals from Iran [Internet]. Tobacco Control 26:674–682, 2017[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/26/6/674.

Fararouei M, Iqbal A, Rezaian S et al. Dietary Habits and Physical Activity are Associated With the Risk of Breast Cancer Among Young Iranian Women: A Case-control Study on 1010 Premenopausal Women [Internet]. Clinical Breast Cancer 19:e127–e134, 2019[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.clinical-breast-cancer.com/article/S1526-8209(18)30622-0/fulltext.

Ghiasvand R, Bahmanyar S, Zendehdel K et al. Postmenopausal breast cancer in Iran; risk factors and their population attributable fractions [Internet]. BMC Cancer 12:414, 2012[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-414.

Habibi N, Nassiri-Toosi M, Sharafi H et al. Aflatoxin B1 exposure and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in Iranian carriers of viral hepatitis B and C [Internet]. Toxin Reviews 38:234–239, 2019[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1080/15569543.2018.1446027.

Hajjar M, Rezazadeh A, Naja F et al. Association of Recommended and Non-Recommended Food Score and Risk of Bladder Cancer: A Case-Control Study [Internet]. Nutrition and Cancer 74:2105–2112, 2022[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2021.2004172.

Hosseini F, Shab-Bidar S, Ghanbari M et al. Food Quality Score and Risk of Breast Cancer among Iranian Women: Findings from a Case Control Study [Internet]. Nutrition and Cancer 74:1660–1669, 2022[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2021.1957136.

Marzbani B, Nazari J, Najafi F et al. Dietary patterns, nutrition, and risk of breast cancer: a case-control study in the west of Iran [Internet]. Epidemiol Health 41:e2019003, 2019[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: http://www.e-epih.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.4178/epih.e2019003.

Narmcheshm S, Sasanfar B, Hadji M et al. Patterns of Nutrient Intake in Relation to Gastric Cancer: A Case Control Study [Internet]. Nutrition and Cancer 74:830–839, 2022[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2021.1931697.

Nasrollahzadeh D, Kamangar F, Aghcheli K et al. Opium, tobacco, and alcohol use in relation to oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a high-risk area of Iran [Internet]. Br J Cancer 98:1857–1863, 2008[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/6604369.

Rafeemanesh E, Taghizadeh Kermani A, Khajedaluee M et al. Evaluation of Breast Cancer Risk in Relation to Occupation [Internet]. Middle East Journal of Cancer 9:186–194, 2018[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://mejc.sums.ac.ir/article_42122.html.

Salarabadi A, Bidgoli SA, Madani SH. Roles of Kermanshahi Oil, Animal Fat, Dietary and Non-Dietary Vitamin D and other Nutrients in Increased Risk of Premenopausal Breast Cancer: A Case Control Study in Kermanshah, Iran [Internet]. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 16:7473–7478, 2015[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: http://koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO201501255363238.page.

Simonian M, Khosravi S, Mortazavi D et al. Environmental Risk Factors Associated with Sporadic Colorectal Cancer in Isfahan, Iran [Internet]. Middle East Journal of Cancer 9:318–322, 2018[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://mejc.sums.ac.ir/article_42144.html.

Toorang F, Sasanfar B, Hekmatdoost A et al. Macronutrients Intake and Stomach Cancer Risk in Iran: A Hospital-based Case-Control Study [Internet]. Journal of Research in Health Sciences 21, 2021[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: http://jrhs.umsha.ac.ir/index.php/JRHS/article/view/6102.

Wang Q, Hashemian M, Sepanlou SG et al. Dietary quality using four dietary indices and lung cancer risk: the Golestan Cohort Study (GCS) [Internet]. Cancer Causes Control 32:493–503, 2021[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01400-w.

Khodakarami N, Clifford GM, Yavari P et al. Human papillomavirus infection in women with and without cervical cancer in Tehran, Iran [Internet]. International Journal of Cancer 131:E156–E161, 2012[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.26488.

Khodavandi A, Yaghobi R, Alizadeh F, et al. Evaluation of GB virus C (GBV-C)/hepatitis G virus (HGV) and hepatitis type B virsuses (HBV) infections in patients with Non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5:4143–9.

Rezaeian AA, Yaghobi R, Nia MR, et al. Etiology of hepatitis G virus (HGV) and hepatitis type C virus (HCV) infections in non-hodgkin’s lymphoma patients in Southern Iran. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012;11:11659–64.

Mazdak H, Mazdak M, Jamali L, et al. Determination of prostate cancer risk factors in Isfahan, Iran: a case-control study. Med Arh. 2012;66:45–8.

Al-Amad SH, Awad MA, Nimri O. Oral cancer in young Jordanians: potential association with frequency of narghile smoking [Internet]. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology 118:560–565, 2014[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.oooojournal.net/article/S2212-4403(14)00677-4/fulltext.

Dar NA. Narghile Smoking is Associated With the Development of Oral Cancer at Early Age [Internet]. Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice 15:126–127, 2015[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1532338215000809.

Shivappa N, Hébert JR, Steck SE et al. Dietary inflammatory index and odds of colorectal cancer in a case-control study from Jordan [Internet]. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 42:744–749, 2017[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2017-0035.

Bedwani R, El-Khwsky F, Renganathan E et al. Epidemiology of bladder cancer in Alexandria, Egypt: Tobacco smoking [Internet]. International Journal of Cancer 73:64–67, 1997[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/%28SICI%291097-0215%2819970926%2973%3A1%3C64%3A%3AAID-IJC11%3E3.0.CO%3B2-5.

Zheng Y-L, Amr S, Saleh DA et al. Urinary Bladder Cancer Risk Factors in Egypt: A Multicenter Case–Control Study [Internet]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 21:537–546, 2012[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0589.

Charafeddine MA, Olson SH, Mukherji D et al. Proportion of cancer in a Middle eastern country attributable to established risk factors [Internet]. BMC Cancer 17:337, 2017[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3304-7.

Mhawej R, Ghorra C, Naderi S et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and clinicopathological associations in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in the Lebanese population [Internet]. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology 132:636–641, 2018[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-laryngology-and-otology/article/abs/human-papillomavirus-prevalence-and-clinicopathological-associations-in-oropharyngeal-squamous-cell-carcinoma-in-the-lebanese-population/8052859F66BF656CD74C0BFCAF92F20F.

Elkum N, Al-Tweigeri T, Ajarim D et al. Obesity is a significant risk factor for breast cancer in Arab women [Internet]. BMC Cancer 14:788, 2014[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-788.

Azzeh FS, Hasanain DM, Qadhi AH et al. Consumption of Food Components of the Mediterranean Diet Decreases the Risk of Breast Cancer in the Makkah Region, Saudi Arabia: A Case-Control Study [Internet]. Frontiers in Nutrition 9, 2022[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.863029.

Dosemeci M, Gokmen I, Unsal M et al. Tobacco, alcohol use, and risks of laryngeal and lung cancer by subsite and histologic type in Turkey [Internet]. Cancer Causes Control 8:729–737, 1997[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018479304728.

Kaya H, Polat Mf, Erdem F et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus and hepatitis G virus in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [Internet]. Clinical & Laboratory Haematology 24:107–110, 2002[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2257.2002.00427.x.

Abdel-Salam A-SG, Mollazehi M, Bandyopadhyay D et al. Assessment of lung cancer risk factors and mortality in Qatar: A case series study [Internet]. Cancer Reports 4:e1302, 2021[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1002/cnr2.1302.

Khlifi R, Olmedo P, Gil F et al. Blood nickel and chromium levels in association with smoking and occupational exposure among head and neck cancer patients in Tunisia [Internet]. Environ Sci Pollut Res 20:8282–8294, 2013[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-013-1466-7.

Nasher AT, Al-hebshi NN, Al-Moayad EE et al. Viral infection and oral habits as risk factors for oral squamous cell carcinoma in Yemen: a case-control study [Internet]. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology 118:566–572.e1, 2014[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.oooojournal.net/article/S2212-4403(14)00682-8/fulltext.

Sasco AJ, Merrill RM, Dari I et al. A case–control study of lung cancer in Casablanca, Morocco [Internet]. Cancer Causes Control 13:609–616, 2002[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019504210176.

Harfouch RM, Alkhaier Z, Ismail S, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of colorectal cancer in Syria: a single-center retrospective study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:4654–8.

Taha Z, Eltom SE. The Role of Diet and Lifestyle in Women with Breast Cancer: An Update Review of Related Research in the Middle East [Internet]. BioResearch Open Access 7:73–80, 2018[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1089/biores.2018.0004.

Tanner LTA, Cheung KL. Correlation between breast cancer and lifestyle within the Gulf Cooperation Council countries: A systematic review [Internet]. World Journal of Clinical Oncology 11:217–242, 2020[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v11/i4/217.htm.

Al-Jaber A, Al-Nasser L, El-Metwally A. Epidemiology of oral cancer in Arab countries [Internet]. Saudi Medical Journal 37:249–255, 2016[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://smj.org.sa/content/37/3/249.

Alqahtani WS, Almufareh NA, Al-Johani HA et al. Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancers and Possible Risk Factors Across Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: A Systematic Review [Internet]. World J Oncol 11:173–181, 2020Available from: https://www.wjon.org/index.php/wjon/article/view/1283.

Obeid DA, Almatrrouk SA, Alfageeh MB et al. Human papillomavirus epidemiology in populations with normal or abnormal cervical cytology or cervical cancer in the Middle East and North Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. Journal of Infection and Public Health 13:1304–1313, 2020[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034120305220.

Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J et al. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population [Internet]. Int J Obes 32:959–966, 2008[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/ijo200811.

Shakeri J, Golshani S, Jalilian E et al. Studying the Amount of Depression and its Role in Predicting the Quality of Life of Women with Breast Cancer [Internet]. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP 17, 2016[cited 2023 Jun 25] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26925657/.

Türkdoğan MK, Kilicel F, Kara K et al. Heavy metals in soil, vegetables and fruits in the endemic upper gastrointestinal cancer region of Turkey [Internet]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 13:175–179, 2003[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1382668902001564.

Tran KB, Lang JJ, Compton K et al. The global burden of cancer attributable to risk factors, 2010–19: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 [Internet]. The Lancet 400:563–591, 2022[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)01438-6/fulltext.

Rahal Z, El Nemr S, Sinjab A et al. Smoking and Lung Cancer: A Geo-Regional Perspective [Internet]. Frontiers in Oncology 7, 2017[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2017.00194.

Benbrahim Z, Antonia T, Mellas N. EGFR mutation frequency in Middle East and African non-small cell lung cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. BMC Cancer 18:891, 2018[cited 2023 Jul 27] https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4774-y.

World Health Organization.: WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2015 [Internet]. World Health Organization, 2015[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/156262.

Kadhum M, Sweidan A, Jaffery AE et al. A review of the health effects of smoking shisha [Internet]. Clinical Medicine 15:263–266, 2015[cited 2023 Jul 27] Available from: https://www.rcpjournals.org/content/clinmedicine/15/3/263.

Al-Lawati J, Mabry RM, Al-Busaidi ZQ. Tobacco Control in Oman: It’s Time to Get Serious! [Internet]. Oman Med J 32:3–14, 2017[cited 2023 Dec 26] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5187396/.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: AM, MA, AI, HA, data collection RM, AA, analysis and interpretation of results: RM, and manuscript preparation: RM, AA, AM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary File A.

Detailed search strategy

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mansour, R., Al-Ani, A., Al-Hussaini, M. et al. Modifiable risk factors for cancer in the middle East and North Africa: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 24, 223 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-17787-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-17787-5