Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is among the most common cancers globally with a projected increase in incidence and mortality in low- and middle-income countries. The majority of the patients in East Africa present with advanced disease contributing to poor disease outcomes. Breast cancer screening enables earlier detection of the disease and therefore reduces the poor outcomes associated with the disease. This study aims to identify and synthesize the reported barriers and enablers of breast cancer screening among East African women.

Methods

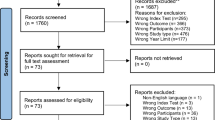

Medline, Embase, SCOPUS, and Cochrane library were searched for articles published on the subject from start to March 2022 using PRISMA guidelines. Also, forward citation, manual search of references and searching of relevant journals were done. A thematic synthesis was carried out on the “results/findings” sections of the identified qualitative papers followed by a multi-source synthesis with quantitative findings.

Results

Of 4560 records identified, 51 were included in the review (5 qualitative and 46 quantitative), representing 33,523 women. Thematic synthesis identified two major themes – “Should I participate in breast cancer screening?” and “Is breast cancer screening worth it?”. Knowledge of breast cancer and breast cancer screening among women was identified as the most influencing factor.

Conclusion

This review provides a rich description of factors influencing uptake of breast cancer screening among East African women. Findings from this review suggest that improving knowledge and awareness among both the public and providers may be the most effective strategy to improve breast cancer screening in Eastern Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer (BC) is among the most commonly diagnosed malignancy globally [1, 2]. According to GLOBOCAN 2020, BC accounted for the majority of new cancer cases diagnosed globally (2.3million people diagnosed) and contributed to 6.9% of cancer-related deaths (ranked fifth after lung (18%), colorectal (9.4%), liver (8.3%) and stomach cancers (7.7%)) [3]. It is projected that its incidence will continue to increase, mostly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) as a result of population aging and increased adoption of high-risk lifestyles [2, 4].

The distribution of BC varies between countries, the incidence being higher in high-income countries (HICs) than LMICs though most of the deaths related to BC occur in LMICs [3]. LMICs face an unproportionally high burden of disease compared to HICs due to the majority of the patients presenting with advanced disease necessitating complex treatment options which are often absent in these areas [5, 6].

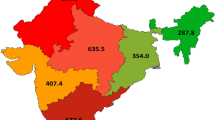

Sub-Saharan Africa has experienced rapid increase in BC incidence over the last 20-30 years, and it has the highest mortality rates in the world [3, 7]. This has been attributed to delayed patient presentation and weak health infrastructure [5, 7]. Delayed presentations have been attributed to – inefficient screening services, insufficient healthcare infrastructure, unavailability and high cost of cancer services, and low patient awareness about the disease [8,9,10,11,12]. In East Africa (EA), the incidence of BC in 2020 was estimated at 33 per 100,000 person-years, whereas the mortality was estimated at 17.9 per 100,000 person-years (compared 50.4 vs 15.7 in Southern Africa, 41.5 vs 22.3 in Western Africa and 32.7 vs 18 in Central Africa, incidence vs mortality rate per 100,000 persons) [3].

The disease stage at the time of diagnosis is a significant determinant of survival. Early-stage disease is associated with better survival than advanced disease [7, 13]. Due to most patients in Sub-Saharan Africa presenting with advanced disease, it is imperative to improve programs (such as breast cancer screening) that will increase the early detection of disease. Efforts to promote screening, followed by early and appropriate treatment are essential components to improving survival. Whereas screening programs focus on asymptomatic patients, early detection programs focus on patients with early symptoms of disease, both being essential in early cancer diagnosis.

Breast cancer screening (BCS) methods commonly used in East Africa (EA) are – self-breast examination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE), ultrasonography and mammography [14]. Mammography is currently the gold standard of BCS [14]. Most guidelines recommend annual or biennial mammographic screening between 40 and 74 years for average-risk populations and annual mammography or annual magnetic resonance imaging starting from a younger age for high-risk populations. In resource-limited settings like EA, population-based mammography screening has not been considered to be cost-effective and other cost-effective methods (CBE and BSE) have to be used [3]. Other methods of BCS that are available though not commonly used in East Africa are; magnetic resonance imaging, molecular imaging and genetic testing [14].

Primary studies from EA have reported low uptake of BCS services, particularly mammography [8,9,10,11,12]. Several factors proposed as influencing screening uptake in other Sub-Saharan countries include – knowledge about BC and BCS, socio-cultural factors, economic factors, perception and attitude toward BC and BCS, provider factors and other related factors [1, 15,16,17]. We have identified no study that has systematically gathered evidence for factors influencing breast screening uptake in the EA region. East African region has been defined to include the countries Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda [18, 19].

In this study, we aimed to systematically review the published literature on the status of breast cancer screening in East Africa by examining the factors associated with uptake of the various methods used for BCS. We targeted Eastern Africa as it was shown that the cumulative risk of dying from cancer from women in 2020 according to GLOBOCAN was higher in Eastern Africa (11%) compared to other regions of the world [3]. results from this study may help policymakers and other stakeholders to identify gaps in breast cancer management and device pathways to improve early disease detection and reduce adverse outcomes.

Methods

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [20].

Search strategy

A comprehensive electronic database literature search was conducted in March 2022 using Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE and SCOPUS. To complement the database search, forward citation tracking and examination of reference lists of relevant studies were conducted. Finally, hand searching for articles in the following libraries was undertaken – African Journals Online, DiscoverEd, and Pan-African Medical Journal.

Population, intervention, comparison outcomes, timing and study type (PICOTS) approach was used to generate groups of medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and keywords. (See Table 1 for search terms and Additional file 1 for full MEDLINE search):

-

Population – women residing in East African countries (as defined in the background).

-

Intervention – any breast cancer screening method used.

-

Comparison – not applicable

-

Outcomes – influencers (barriers and facilitators) of breast cancer screening uptake.

-

Timing – from start to March 2022 (included studies ranged from 2010 to 2022)

-

Study type – quantitative studies, qualitative studies and primary mixed methods studies published in peer-reviewed journals.

To maximize retrieval of all relevant articles to give a complete picture of factors influencing BCS, the year of publication limitation was not imposed. Boolean operators “OR”, and “AND”, were used to include, and restrict search terms.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows.

-

1.

Population – studies conducted among women in Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Rwanda, Tanzania, or Uganda, regardless of race or ethnicity.

-

2.

Intervention – studies reporting the use of any method of BCS.

-

3.

Outcomes – studies reporting factors associated with uptake of BCS.

-

4.

Study design – quantitative studies, qualitative studies and primary mixed methods studies published in peer-reviewed journals.

-

5.

Studies reported in English.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Studies reporting BCS that failed to indicate factors related to the use/non-use of screening methods.

-

2.

Studies where barriers/facilitators are not related to BCS.

-

3.

Studies among women from East Africa residing in non-EA countries

-

4.

Studies published in languages other than English

-

5.

Grey literature, reviews, editorial, letter, book chapters, as well as abstracts with no full text were excluded.

Study selection

All articles were retrieved through the electronic search process and entered into an EndNote bibliographic database. All retrieved studies had their titles and abstracts screened to assess for eligibility after duplicates were removed. Full-text articles were retrieved if eligibility was met and for those in doubt.

Quality assessment

Qualitative studies were qualified using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality assessment tool (http//www.casp-uk.net). Quantitative studies were assessed using JBI’s cross-sectional critical appraisal tool (jbi. global/critical-appraisal-tools) (see Additional file 2 for criteria used for quality assessment). For both tools, each criterion was given a score from 0–2 based on the author’s judgement. These were then summed and an assessment of the overall quality of a study was ranked as “good”, “fair”, and “poor”. The quality score for quantitative studies ranged from 0–40 (0–20 = poor, 21–30 = fair, 21–40 = high). The quality score for qualitative studies ranged from 0–36 (0–18 = poor, 19–28 = fair, 29–36 = good). No studies were excluded as a result of the quality assessment, rather, the quality assessment contributed to the confidence of each finding.

Data extraction and synthesis

Key data from each of the included papers were extracted using a template. Extracted data included the name of the first author; year of publication; country of study; study aims, design, setting, and demographics; data collection methods; sampling technique and sample size; BCS method investigated; and factors related to uptake of screening method(s).

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis for qualitative studies followed Thomas and Harden’s (2008) thematic synthesis approach [21]. All data found in the “findings” and/or “results” sections of both the abstracts and the main texts, including quotations from the study participants were exported verbatim into N-Vivo (N Vivo Qualitative Research Data Analysis Software QSR International Pty Ltd. 2020). Extracts were read and re-read followed by coding line by line. The codes were then grouped into clusters and finally into themes. Identified themes were examined for interconnectedness with included quantitative studies and the findings from the quantitative papers were absorbed within the themes using multi-source synthesis method [22]. Multi-source synthesis method was used as it offers a step by step approach to synthesis of data from multiple sources (both qualitative and quantitative) to reach a broader conclusion.

Narrative synthesis for quantitative studies following Popay et al., (2006), guidance for the conduct of narrative synthesis for systematic reviews [23], is provided in Additional file 3.

Results

Study characteristics

The initial search yielded 4560 studies, out of which 51 were selected for inclusion in the study (see PRISMA flowchart in Fig. 1). Of the 51 included studies, five employed qualitative (Ethiopia = 2, Kenya = 2, Uganda = 1), and 46 quantitative methods of data collection (Eritrea = 1, Ethiopia = 33, Kenya = 4, Tanzania = 2, Uganda = 6). These represented data from 33,523 participants (22 breast cancer patients and 33,501 asymptomatic women) from five countries – Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. The study characteristics are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Qualitative studies

Four of the studies used focus group discussions, and one used in-depth interviews. The sample size ranged from 24–80. They all assessed barriers/facilitators for all BCS methods, the study population being community women (with and without BC) and health care providers. The quality of the included studies ranged from medium (n = 3) to high (n = 2). Table 2 shows the study characteristics of the included qualitative studies.

Quantitative studies

Of the 46 included studies, 39 were cross-sectional studies, and seven were surveys. Questionnaires were employed in the studies. The sample size ranged from 98 [24] to 14,734 [25]. Most studies did not indicate a participant’s age limit, though it ranged from as low as 15 years of age [22] to as high as 70 years of age [8, 26].

Studies that focused on breast self-examination (BSE) were 32. Three studies focused on both BSE and clinical breast examination (CBE), one study focused on mammography alone, while ten involved three methods of BCS (BSE, CBE, and mammography). Study population included female university students (n = 13), community women (n = 23), and healthcare workers (n = 11). Quality of included studies ranged from poor (n = 6), fair (n = 29) and good (n = 11). Table 3 shows the study characteristics of the included quantitative studies.

Synthesis results

Based on the response of the participants with regards to barriers and/or facilitators of BCS uptake, two major themes were identified; (a) should I participate in screening? and, (b) is breast cancer screening worth it? (Table 4 shows themes and subthemes). Figure 2 shows the interaction of these themes and the subthemes influencing them.

Theme 1: Should I participate in the screening?

The first major theme was related to the relevance and importance of BCS as seen by the women, and ultimately whether they should participate in it. Women’s participation in BCS was largely influenced by four things (sub-themes) – current health status, perceived risk of having BC, awareness of BC and BCS, and perceived benefit in screening.

Current health status

Women explicitly discussed the absence of breast symptoms and being generally healthy as an indication that screening was not required [27, 28, 35, 37, 40, 54, 57, 59]. Additionally, in the study by Muthoni and Miller (2010), some women also responded that they would be wasting the provider’s time if they asked for screening without any complaint [27].

Awareness of BC and BCS

A vast majority of the women confessed to having no idea about the different methods of BCS, how to perform BSE, how often to have a breast examined and where to be examined [9, 26, 28, 30, 42, 43, 49, 56]. This lack of information seemed to affect rural women more as they lack sources of information about BC and BCS [28, 42, 43]. Multivariate analysis showed those with poor knowledge and awareness of BC and BCS were less likely to undergo BCS [26, 36, 48, 51].

Further, those with higher levels of education were more likely to be knowledgeable about BC and BCS and also more likely to undertake BCS compared to those with lower levels of education [14, 15, 24, 38, 50, 61, 64, 67]. This could be related to education providing an avenue for learning health issues like BCS [45]. Additionally, older women were shown to be more likely to participate in BCS compared to younger women, as they were more knowledgeable on health issues and also aware of the relationship between age and BC susceptibility [16, 25, 45, 64].

Perceived risk of having breast cancer

There was generally a low self-susceptibility to BC due to various socio-cultural beliefs on the causes of BC [11, 42, 44, 45, 47, 60, 62]. These beliefs included BC being a result of sin, promiscuity, curses, and deviation from the socio-cultural norm [42, 43]. A 39 year-old participant from a study by Agide et al., (2019) [42] said,

“As to me, doing good or bad acts will determine the occurrence of a disease. A good act leads to good health and a bad leads to disease…” [42].

Family history was often indicated as a risk factor for BC, and some women interpreted its absence as an indication of being at lower risk of having BC and thus no value in BCS [27, 39, 41, 51, 55, 61].

Value of screening

Some women expressed the value of BCS as it could identify problems early and allow appropriate treatment, it would increase their chances of survival and decrease treatment costs if caught early, and it would also help prepare their families for the possibility of death and thus make it easier to cope emotionally with the condition [27, 43]. Women who perceived BCS to be beneficial had odds higher odds of practice [32, 34, 39, 44].

Another group of women saw no advantage in undergoing BCS. Most women viewed BC as a terminal disease with no advantage in early detection practice [27, 42, 43]. Others believed that cancer is a result of supernatural causes and there is therefore no point in screening [42, 43, 57]. This view prevented some from undergoing screening as they relied on prayers as a means to prevent diseases and some religious organizations prohibited their followers from going to the hospital [43]. A 22-year-old asymptomatic participant from Agide et al., (2019) [42] stated,

“I think it is common for all of us to perceive BC as it is not a curable disease. Since the cancer treatment is found outside the country, it is not affordable and the only option is death. For the question, you asked as ‘do women prefer to use screening as a primary prevention method?’ In my opinion, I don’t think so” [42].

Theme 2: Is breast cancer screening worth it?

The second theme is related to women’s burden – both physically and emotionally in undergoing breast cancer screening. This relates to experiences in undertaking BCS.

Emotional experiences

Having a diagnosis of BC is a very crippling emotional experience as described by several women [27, 28, 42, 49]. They expressed emotions of low self-esteem and anxiety if they were found to have BC from screening, and also doubts with regards to the quality of life after diagnosis and treatment and the state of their families and children if they become debilitated or die [28, 43, 46]. Wachira et al., also noted other women are embarrassed to undergo CBE [62].

Fear of BC diagnosis

Another emotional experience acting as a barrier to women opting to undertake BCS was fear of diagnosis [35, 54, 58, 62]. This fear stemmed from the possibility of having to undergo surgery and the possibility of dying if BC was diagnosed [43, 49]. A key informant in a study by Ilaboya et al., (2018) [28] stated,

“So many people even fear to go for screening because they say ‘why go? Because if they discover cancer I am doomed to die.’ So they have that feeling that once detected it won’t be cured” [28].

Fear was also related to the social threat of being divorced, and being infertile if they underwent mastectomy due to the disease [43, 49]. Such emotional experiences were described as barriers to screening even among women with a positive attitude toward BCS [27, 43].

Experience with healthcare professionals

Women’s motivation for screening was often shaped by the quality of their interaction with the healthcare workers. Some women recalled negative encounters, with poor communication cited as the reason they did not pursue further screening [27, 43]. Women preferred to receive care from tertiary institutions rather than primary care facilities, as they felt they received better care in tertiary facilities [28, 63]. Ilaboya et al., (2018) [28], also reported a general perception among community participants that the healthcare workers in primary care settings were inexperienced [28]. This was shown by focus group discussions among healthcare workers that revealed a low level of awareness about BC and BCS [28, 43].

Accessibility of BCS services

Several women reported they were unable to access BCS services due to long distance to health facilities [15, 25, 49, 64, 67], absence of screening services in primary care settings [28, 49] and also the high cost of services [27, 42, 58, 62]. For others, screening was seen as inaccessible due to long waiting times in health facilities that deterred them from pursuing BCS [28, 43, 62].

Social support

Some women described how screening was another demand on their time and often competed with other daily tasks [27, 56, 62]. Various women discussed how their duties in the family prevented them from health-seeking activities such as educational forums and screening programs [27, 43, 49]. Married women and single mothers voiced their concerns about how overwhelming their duties can be [27, 43, 49].

Married women in particular cited their husbands as prohibitors to health activities due to the husband’s position as the “head of the home” [27, 43]. Despite this, various multivariate analyses showed married women to have better odds of practicing BCS compared to those not married [25, 32, 41, 58, 65]. Of note, Minasie et al., (2017) and Sharp et al., (2019), reported that married with poor social support have lower BCS practices [45, 58].

Individual and family financial circumstances

Finances affected screening services in a variety of ways including preference of screening method, access to screening services (service cost and transport cost) and perceived benefit of screening (economic advantage of screening) [27, 28, 42, 43, 49].

Women were less likely to undertake CBE and mammography due to their cost and preferred BSE as expressed by a participant’s preference for BSE because,

“…it is convenient as it doesn’t cost anything” [11].

Expenses to access screening services (CBE and mammography) were rooted in transport-related costs, and the cost of the services [12, 25, 27, 43, 49, 58]. Others saw no direct financial advantage in undergoing screening [28, 43, 49] as is illustrated by a 60 year old rural participant,

“I am not going for BCS. They are not going to give me food so let me go to my garden and dig. Am I going to eat from there? Do they eat cancer? I don’t want to do it” [28].

Perceived financial benefit of BCS could be the reason why self-employed and unemployed women were less likely compared to those who were employed to undergo BCS [11, 43, 47, 53, 55]. It could also be attributed to income level, as those with lower income are less likely to undergo BCS compared to those with better income [24, 33, 34, 60, 65]. Additionally, women with a longer duration of employment and those with employed husbands were more likely to participate in BCS [12, 13].

Discussion

This review examined the evidence for factors influencing BCS practice among women in Eastern Africa (EA). It has generated an understanding of how BCS is experienced by women in EA and reveals findings that are important for expanding BCS in the region and other similar countries around the world. The main finding was that lack of knowledge and awareness about BC and BCS were the key barriers to BCS irrespective of country, study population or methodology. Two other important observations made in this study were the effect of social roles among women in EA and the accessibility of BCS services.

An appreciation of how Eastern African women perceive their social roles helps understand how their roles affect screening practices. This is because several women reported a lack of support in their household duties as a barrier to attending health forums and screening activities [27, 28, 43]. Women’s role in this region as mothers and wives is to act as a caretaker of the family, which means they sometimes put their family’s needs above their own [2, 68]. Studies in East Africa have shown women to have lower autonomy on matters of their health [69,70,71]. Lack of home support and autonomy in health decisions has also been reported in studies done in Asia and among Asians, Hispanics and Blacks living in high income countries [72,73,74,75,76]. Women globally need to be supported and encouraged to participate in such screening activities that can have a profound impact on their livelihoods.

Another observation made is the need for resource allocation and facilitation of educational programs at the patient and provider levels. The effect of lack of knowledge identified included women who do not know screening is required, do not know where to go for screening, do not know how to perform BSE, have limited knowledge about screening methods, and lack knowledge about BC (cause, signs and symptoms, treatment and prognosis). Poor knowledge regarding breast cancer has also been observed in other countries in Africa, Asia, Europe and USA, and this has consistently been indicated as a barrier to participating in breast cancer screening [1, 15, 73, 74, 76,77,78,79]. In settings with limited resources like EA countries, the approach might focus on enhanced awareness and capacity building for breast evaluation [16, 80].

Studies done in other India and Mexico indicate low levels of cancer awareness even among those with higher education or socioeconomic status [81, 82]. However, the Global Breast Cancer Initiative indicates that with financial and educational investment to improve cancer literacy in LMICs, the public may be more likely to utilize screening programs [83]. Studies done in Africa and Asia have also shown increased utilization of breast cancer screening services among patients with higher levels of education and socioeconomic status [1, 15, 73,74,75]. Results from this suggest that providers, especially those from primary care settings require more rigorous training programs for early detection methods and guidelines, this also includes training on patient-provider interactions [17]. Pace and Shulman (2016) suggested quality control and ongoing training of practitioners in CBE must be an essential part of a CBE early detection program [16].

Another major component is that screening services are less accessible, especially in rural settings. Screening services are expensive and unavailable in most African countries, this is contrast to studies done in Asia, Europe and America where breast cancer screening services are more available though not readily accessible due to cost [1, 15, 72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. Decentralization of screening services tailored to EA rural areas will enhance the availability of screening services [84]. Pace and Shulman (2016) reported that even without systematic screening or early detection campaigns, the development of more accessible health facilities leads to a shift in the stage distribution of breast cancer over time [16]. These can include the use of mobile clinics in areas with limited healthcare infrastructure, and subsidized or free screening services [17].

Based on this review, several priorities need to be considered for the development and implementation of breast cancer screening in EA. These include financial and resource allocation to;

-

1.

Community education programs to facilitate screening uptake

-

2.

Enhanced training for healthcare providers particularly those in the primary care settings

-

3.

Decentralization of screening activities to meet the needs of under-resourced populations, especially in rural areas.

The main challenge in screening interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa is the gap between conducting a good screening program and appropriate follow-up with diagnosis and treatment [16, 17]. Strategic investments in cancer control and implementation to ensure universal access to cancer are required to achieve the Sustainable Developmental Goals [85]. The World Health Organization highlighted financing, partnership, legislative frameworks, policy integration, leadership and advocacy, and development and allocation of human resources as key aspects to facilitate effective policy development [86].

Strengths of the review

To our knowledge, this is the first review that systematically summarized studies on factors influencing BCS among women in Eastern Africa. We performed an extensive systematic search of the literature with no limitation on time. We included both qualitative and quantitative studies investigating BCS uptake and associated factors among EA countries. A thematic synthesis of the factors influencing breast cancer screening uptake was done together with a multisource synthesis of qualitative and quantitative data. Quality appraisal of the included studies was done, and no study was refuted based on quality.

Limitations of the review

The findings from this review are subject to the following limitations. First, we found no data from Burundi, Comoros, Djibouti, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan, we, therefore, have no insight into these countries. Secondly, there was a variation in methodology among quantitative studies which precluded meta-analysis of factors associated with screening practices. Meta-analysis would predict the effect size of each factor. Third, since the literature search and selection process was done in English, relevant articles in other languages were not identified. Also, exclusion of unpublished reports, review articles, conference abstracts and thesis may have omitted relevant information. Lastly, we did not assess for publication bias.

Conclusion

In this review, many factors were identical irrespective of the country where the study was done. Improving knowledge and awareness among both the public and providers may be the most effective strategy to improve BCS in Eastern Africa. Breast health awareness should be promoted, effective training of relevant staff in CBE should be done, opportunistic CBE screening has to be encouraged and the feasibility of mammography has to be evaluated. There is a need to strengthen political will toward these core policy features to develop robust national breast cancer screening programs. Increased financial, human, and research efforts are also needed to sufficiently address the existing and increasing need for cancer services.

Overall, this review has highlighted that whilst there is a range of publications reporting the practice of BCS and associated factors in women in EA, there remains a significant scant body of evidence describing BCS practices in this region as most identified studies came from Ethiopia, and also majority focused on BSE. This review can be used as a starting point for further research into this problematic area of primary public health practice.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- BCS:

-

Breast cancer screening

- BSE:

-

Self breast examination

- CBE:

-

Clinical breast examination

- EA:

-

East Africa

- HICs:

-

High income countries

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- RS:

-

Radiological screening

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

References

Ba DM, Ssentongo P, Agbese E, Yang Y, Cisse R, Diakite B, et al. Prevalence and determinants of breast cancer screening in four sub-Saharan African countries: a population-based study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10): e039464.

Chao CA, Huang L, Visvanathan K, Mwakatobe K, Masalu N, Rositch AF. Understanding women’s perspectives on breast cancer is essential for cancer control: knowledge, risk awareness, and care-seeking in Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):930.

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Joko-Fru WY, Jedy-Agba E, Korir A, Ogunbiyi O, Dzamalala CP, Chokunonga E, et al. The evolving epidemic of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: results from the African cancer registry network. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(8):2131–41.

Ginsberg GM, Lauer JA, Zelle S, Baeten S, Baltussen R. Cost effectiveness of strategies to combat breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia: mathematical modelling study. BMJ. 2012;344: e614.

Smith RA, Caleffi M, Albert U-S, Chen THH, Duffy SW, Franceshi D, et al. Breast cancer in limited-resource countries: early detection and access to care. Breast J. 2006;12(1):s16–26.

Black E, Richmond R. Improving early detection of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: why mammography may not be the way forward. Global Health. 2019;15(1):3.

Abay M, Tuke G, Zewdie E, Abraha TH, Grum T, Brhane E. Breast self-examination practice and associated factors among women aged 20–70 years attending public health institutions of Adwa town, North Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):622–8.

Abeje S, Seme A, Tibelt A. Factors associated with breast cancer screening awareness and practices of women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 11 medical and health sciences 1117 public health and health services 11 medical and health sciences 1112 oncology and carcinogenesis. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):8.

Dagne AH, Ayele AD, Assefa EM. Assessment of breast self- examination practice and associated factors among female workers in Debre Tabor Town public health facilities, North West Ethiopia, 2018: Cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):11.

Elsie KM, Gonzaga MA, Francis B, Michael KG, Rebecca N, Rosemary BK, et al. Current knowledge, attitudes and practices of women on breast cancer and mammography at Mulago Hospital. Pan Afr Med J. 2010;5:9.

Joyce C, Ssenyonga LVN, Iramiot JS. Breast self-examination among female clients in a tertiary hospital in Eastern Uganda. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2020;2020(12):6.

Dibisa TM, Gelano TF, Negesa L, Hawareya TG, Abate D. Breast cancer screening practice and its associated factors among women in Kersa District, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33:144.

Omidiji OA, Campbell PC, Irurhe NK, Atalabi OM, Toyobo OO. Breast cancer screening in a resource poor country: Ultrasound versus mammography. Ghana Med J. 2017;51(1):6–12.

Akuoko CP, Armah E, Sarpong T, Quansah DY, Amankwaa I, Boateng D. Barriers to early presentation and diagnosis of breast cancer among African women living in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2): e0171024.

Pace LE, Shulman LN. Breast cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities to reduce mortality. Oncologist. 2016;21(6):739–44.

Pierz AJ, Randall TC, Castle PE, Adedimeji A, Ingabire C, Kubwimana G, et al. A scoping review: facilitators and barriers of cervical cancer screening and early diagnosis of breast cancer in Sub-Saharan African health settings. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2020;33: 100605.

African Development Bank. East Africa Regional Overview | African Development Bank Group - Making a Difference. 2022. https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/east-africa/east-africa-overview. Accessed 6 July 2023.

Eastern Africa | United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. 2021. https://www.uneca.org/sro-ea. Accessed 6 July 2023.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

Pedersen VH, Dagenais P, Lehoux P. Multi-source synthesis of data to inform health policy. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27(3):238–46.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews; A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster, UK: University of Lancaster; 2006.

Ayugi J, Ndagijimana G, Luyima S, Kitara DL. Breast cancer awareness and downstaging practices among adult women in the Gulu City Main Market, Northern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Med Res Arch. 2022;10(9). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v10i9.3101.

Antabe R, Kansanga M, Sano Y, Kyeremeh E, Galaa Y. Utilization of breast cancer screening in Kenya: what are the determinants? BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):228–37.

Assefa AA, Abera G, Geta M. Breast cancer screening practice and associated factors among women aged 20–70 years in urban settings of SNNPR, Ethiopia. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2021;13:9–19.

Muthoni A, Miller AN. An exploration of rural and urban Kenyan women’s knowledge and attitudes regarding breast cancer and breast cancer early detection measures. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(9):801–16.

Ilaboya D, Gibson L, Musoke D. Perceived barriers to early detection of breast cancer among community health workers in Uganda using a socioecological framework. Global Health. 2018;14(9):10.

Azage M, Abeje G, Mekonnen A. Assessment of factors associated with breast self-examination among health extension workers in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Breast Cancer. 2013;2013:6.

Birhane K, Alemayehu M, Anawte B, Gebremariyam G, Daniel R, Addis S, et al. Practices of breast self-examination and associated factors among female Debre Berhan University Students. International Journal of Breast Cancer. 2017;2017:1–6.

Dinegde NG, Demie TG, Diriba AB. Knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among young women in tertiary education in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2020;12:201–10.

Mekuria M, Nigusse A, Tadele A. Breast self-examination practice and associated factors among secondary school female teachers in gammo gofa zone, southern. Ethiopia Breast Cancer: Targets and Therapy. 2020;12:1–10.

Terfa YB, Kebede EB, Akuma AO. Breast self-examination practice among women in Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2020;12:181–8.

Dagne I, Tesfaye F, Abdulrashid N, Mekonnen R. Breast self-examination practice and associated factors among female healthcare professionals at dire dawa administration, Eastern Ethiopia. European J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2019;6(1):161–9.

Ameer K, Abdulie SM, Pal KS. Breast cancer awareness and practice of breast self-examination among female medical students in Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia. Int J Int Multidiscip Res Stud. 2014;2(2):109–19.

Negeri EL, Heyi WD, Melka AS. Assessment of breast self-examination practice and associated factors among female health professionals in Western Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Int J Med Med Sci. 2017;9(12):148–57.

Natae FS. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of breast selfexamination among Ambo University undergraduate regular female students; 2015. J Med Physiol Biophysi. 2017;2017(32):9–17.

Legesse B, Gedif T. Knowledge on breast cancer and its prevention among women household heads in Northern Ethiopia. Open J Prev Med. 2014;04(01):32–40.

Getu MA, Kassaw MW, Tlaye KG, Gebrekiristos AF. Assessment of breast self-examination practice and its associated factors among female undergraduate students in Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2016. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2019;11:21–8.

Hailu T, Berhe H, Hailu D, Berhe H. Knowledge of breast cancer and its early detection measures among female students, in Mekelle University, Tigray Region, Ethiopia. Scie Hailu T. Knowledge of breast cancer and its early detection measures among female students, in Mekelle University, Tigray Region, Ethiopia. Scie J Clin Medi. 2014;3(4):57–64. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.sjcm.20140304.11.

Wurjine TH, Menji ZA, Bogale N. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice towards breast cancer early detection methods among female health professionals at public health centers of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2017. Womens Health. 2019;8(3):201–2019.

Agide FD, Garmaroudi G, Sadeghi R, Shakibazadeh E, Yaseri M, Koricha ZB. How do reproductive age women perceive breast cancer screening in Ethiopia? a qualitative study. Afr Health Sci. 2019;19(4):3009–17.

Kisiangani J, Baliddawa J, Marinda P, Mabeya H, Choge JK, Adino EO, et al. Determinants of breast cancer early detection for cues to expanded control and care: the lived experiences among women from Western Kenya. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(81):9.

Birhane N, Mamo A, Girma E, Asfaw S. Predictors of breast self - examination among female teachers in Ethiopia using health belief model. Arch Public Health. 2015;73(1):39.

Minasie A, Hinsermu B, Abraham A. Breast self-examination practice among female health extension workers: a cross sectional study in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Reprod Syst Sex Disord. 2017;6(4):8.

Shallo SA, Boru JD. Breast self-examination practice and associated factors among female healthcare workers in West Shoa Zone, Western Ethiopia 2019: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):637–43.

Taklual W, Tesfaw A, Mekie M, Shemelis T. Breast self-examination practice among female undergraduate students in debre tabor university, northcentral Ethiopia: Based on health belief model. Middle East J Cancer. 2021;12(4):563–72.

Urga Workineh M, Lake EA, Adella GA. Breast self-examination practice and associated factors among women attending family planning service in modjo public health facilities southwest ethiopia. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2021;13:459–69.

Getachew S, Tesfaw A, Kaba M, Wienke A, Taylor L, Kantelhardt EJ, et al. Perceived barriers to early diagnosis of breast Cancer in south and southwestern Ethiopia: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):38.

Atuhairwe C, Amongin D, Agaba E, Mugarura S, Taremwa IM. The effect of knowledge on uptake of breast cancer prevention modalities among women in Kyadondo County, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):279.

Gemechu YB, Mitiku J. Assessment of the practice of breast self examination and associated factors among health science female students of Ambo University: Cross sectional study. Health Sci J. 2022;16(5):938. https://doi.org/10.36648/1791-809X.16.5.938.

Kifle MM, Kidane EA, Gebregzabher NK, Teweldeberhan AM, Sielu FN, Kidane KH, et al. Knowledge and practice of breast self examination among female college students in Eritrea. Am J Health Res. 2016;4(4):104–08. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajhr.20160404.16.

Lera T, Beyene A, Bekele B, Abreha S. Breast self-examination and associated factors among women in Wolaita Sodo, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):1.

Mereta B, Shegaze M, Mekonnen B, Desalegn N, Getie A, Abdilwohab MG. Assessment of breast self- examination and associated factors among women age 20–64 years at Arba Minch Zuria District, Gamo Zone SNNPR Ethiopia, 2019. Res Square. 2020;2020:18.

Mihret MS, Gudayu TW, Abebe AS, Tarekegn EG, Abebe SK, Abduselam MA, et al. Knowledge and practice on breast self-examination and associated factors among summer class social science undergraduate female students in the University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;2021:1–9.

Morse EP, Maegga B, Joseph G, Miesfeldt S. Breast cancer knowledge, beliefs, and screening practices among women seeking care at District Hospitals in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2014;8:73–9.

Ng’ida FD, Kotoroi GL, Mwangi R, Mabelele MM, Kitau J, Mahande MJ. Knowledge and practices on breast cancer detection and associated challenges among women aged 35 years and above in Tanzania: a case in morogoro rural district. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2019;2019(11):191–7.

Sharp JW, Hippe DS, Nakigudde G, Anderson BO, Muyinda Z, Molina Y, et al. Modifiable patient-related barriers and their association with breast cancer detection practices among Ugandan women without a diagnosis of breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(6): e0217938.

Tewabe T, Mekuria Z. Knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among undergraduate students in Bahir Dar University, North-West Ethiopia, 2016: A cross-sectional study. J Public Health Afr. 2019;10(1):805.

Zeru Y, Sena L, Shaweno T. Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Associated Factors of Breast Cancer Self-Examination among Urban Health Extension Workers in Addis Ababa, Central Ethiopia. J Midwifery Health. 2018;7(2):1662–72.

Jembere W. Practice of breast self-examination and associated factors among female nurses of Hawassa University comprehensive specialized hospital, South Ethiopia in 2018. Int J Caring Sci. 2019;12(3):1457–66.

Wachira J, Chite AF, Naanyu V, Busakhala N, Kisuya J, Keter A, et al. Barriers to uptake of breast cancer screening in Western Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2014;91(11):391–7.

Scheel RJ, Molina Y, Patrick LD, Anderson OB, Nakigudde G, Lehman DC, et al. Breast cancer downstaging practices and breast health messaging preferences among a community sample of urban and rural Ugandan women. J Global Oncol. 2017;3(2):105–13.

Busakhala NW, Chite FA, Wachira J, Naanyu V, Kisuya WJ, Keter A, et al. Screening by clinical breast examination in Western Kenya: Who Comes? J Global Oncol. 2016;2(3):114–22.

Dellie ST. Knowledge about breast cancer risk-factors, breast screening method and practice of breast screening among female healthcare professionals working in governmental hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2012;2(1):5–12.

Oguta MA, Humwa F. Determinants of knowledge and practice of breast self-examination for detection of breast cancer among women in Kisumu County, Kenya. Int J of Dev Res. 2022;12(03):54686-91. https://doi.org/10.37118/ijdr.24265.03.2022. https://www.journalijdr.com/determinants-knowledge-and-practice-breast-self-examination-detection-breast-cancer-among-women.

Desta F. Knowledge, practice and associated factors of breast self examination among female students of the college of public health and medical science, Jimma University, Ethiopia. Am J Health Res. 2018;6(2):44–50.

Odongo J, Makumbi T, Kalungi S, Galukande M. Patient delay factors in women presenting with breast cancer in a low income country Cancer. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):467. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1438-8.

Alemayehu M, Meskele M. Health care decision making autonomy of women from rural districts of Southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:213–21.

Darteh EKM, Dickson KS, Doku DT. Women’s reproductive health decision-making: a multi-country analysis of demographic and health surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1): e0209985.

Garrison-Desany HM, Wilson E, Munos M, Sawadogo-Lewis T, Maiga A, Ako O, et al. The role of gender power relations on women’s health outcomes: evidence from a maternal health coverage survey in Simiyu region, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):909.

Bea VJ, An A, Gordon AM, Antoine FS, Wiggins PY, Hyman D, Rodriguez ER. Mammography screening beliefs and barriers through the lens of Black women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer. 2023;129(S19):3102–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.34644.

Islam RM, Billah B, Hossain MN, Oldroyd J. Barriers to cervical cancer and breast cancer screening uptake in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(7):1751–63.

Lim YX, Lim ZL, Ho PJ, Li J. Breast cancer in asia: incidence, mortality, early detection, mammography programs, and risk-based screening initiatives. Cancers. 2022;14:4218.

MacKinnon KM, Risica PM, von Ash T, Scharf AL, Lamy EC. Barriers and motivators to women’s cancer screening: a qualitative study of a sample of diverse women. Cancer. 2023;129(S19):3152–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.34653.

Momenimovahed Z,Tiznobaik A, Taheri S, Hassanipour S, Salehiniya H. A review of barriers and facilitators to mammography in Asian women. ecancer 2020, 14:1146; www.ecancer.org; https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2020.1146.

Afaya A, Ramazanu S, Bolarinwa OA, Yakong VN, Afaya RA, Aboagye RG, et al. Health system barriers influencing timely breast cancer diagnosis and treatment among women in low and middle-income Asian countries: evidence from a mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:1601. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08927-x.

Aleshire ME, Adegboyega A, Escontrías OA, Edward J, Hatcher J. Access to care as a barrier to mammography for black women. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2021;22(1):28–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154420965537.

Ponce-Chazarri L, Ponce-Blandón JA, Immordino P, Giordano A, Morales F. Barriers to breast cancer-screening adherence in vulnerable populations. Cancers. 2023;15:604. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030604.

Duggan C, Dvaladze A, Rositch AF, Ginsburg O, Yip CH, Horton S, et al. The breast health global initiative 2018 global summit on improving breast healthcare through resource-stratified phased implementation: methods and overview. Cancer. 2020;126(Suppl 10):2339–52.

Gupta A, Shridhar K, Dhillon PK. A review of breast cancer awareness among women in India: cancer literate or awareness deficit? Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(14):2058–66.

Unger-Saldana K, Ventosa-Santaularia D, Miranda A, Verduzco-Bustos G. Barriers and explanatory mechanisms of delays in the patient and diagnosis intervals of care for breast cancer in Mexico. Oncologist. 2018;23(4):440–53.

Anderson BO, Ilbawi AM, Fidarova E, Weiderpass E, Stevens L, Abdel-Wahab M, et al. The Global Breast Cancer Initiative: a strategic collaboration to strengthen health care for non-communicable diseases. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):578–81.

Songiso M, Pinder LF, Munalula J, Cabanes A, Rayne S, Kapambwe S, et al. Minimizing delays in the breast cancer pathway by integrating breast specialty care services at the primary health care level in Zambia. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:859–65.

World_Health_Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. 2013.

World_Health_Organization. National Cancer Control Programmes, Policies and Managerial Guidelines. 2002.

Acknowledgements

My Masters of Family Medicine studies were funded by the Johnson & Johnson Foundation at the University of Edinburgh.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FMM and DF conceptualized this research. FMM carried out the database search and exclusion. FMM and DOM independently extracted the data. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus among FMM, DOM and DF. FMM and DOM drafted the initial manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search Strategy for MEDLINE

Additional file 2.

Quality assessment tool for the included studies

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Magwesela, F.M., Msemakweli, D.O. & Fearon, D. Barriers and enablers of breast cancer screening among women in East Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 23, 1915 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16831-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16831-0