Abstract

Background

We compared the prevalence of unhealthy lifestyle factors between the hypertensive adults who were aware and unaware of their hypertensive status and assessed the factors associated with being aware of one’s hypertension among adults in Burkina Faso.

Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from the World Health Organization Stepwise approach to surveillance survey conducted in 2013 in Burkina Faso. Lifestyle factors analysed were fruits and vegetables (FV) consumption, tooth cleaning, alcohol and tobacco use, body mass index and physical activity.

Results

Among 774 adults living with hypertension, 84.9% (95% CI: 82.2–87.3) were unaware of their hypertensive status. The frequencies of unhealthy lifestyle practices in those aware vs. unaware were respectively: 92.3% vs. 96.3%, p = 0.07 for not eating, at least, five FV servings daily; 63.2% vs. 70.5%, p = 0.12 for not cleaning the teeth at least twice a day; 35.9% vs. 42.3%, p = 0.19 for tobacco and/or alcohol use; 53.9% vs. 25.4%, p = 0.0001 for overweight/obesity and 17.1% vs, 10.3%, p = 0.04 for physical inactivity. In logistic regression analysis, older age, primary or higher education, being overweight/obese [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 3.2; p < 0.0001], intake of adequate FV servings daily (aOR = 2.9; p = 0.023) and non-use of alcohol and tobacco (aOR = 0.6; p = 0.028) were associated with being aware of one’s hypertensive status.

Conclusion

Undiagnosed hypertension was very high among Burkinabè adults living with hypertension. Those aware of their hypertension diagnosis did not necessarily practise healthier lifestyles than those not previously aware of their hypertension. Current control programmes should aim to improve hypertension awareness and promote risk reduction behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2019, an estimated that 1.28 billon people aged 30–79 years worldwide lived with hypertension of whom 82% lived in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [1]. Over the long term, hypertension leads to increased complications such as heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, disability, and premature mortality [2]. The challenge in reducing the burden of cardiovascular diseases, particularly in LMICs, includes efforts to improve diagnosis and ensure adequate management or treatment for persons living with hypertension [3]. Undiagnosed hypertension and inadequate treatment hinder the effective control of hypertension. Effective strategies for non-pharmacological hypertension management include the adherence to healthy lifestyle and dietary behaviours such as avoidance of tobacco or harmful use of alcohol, weight control, physical activity, fruit and/or vegetables (FV) consumption, as well as oral hygiene [4,5,6,7].

There is some evidence to suggest that persons living with hypertension who are aware of their condition or have knowledge about the disease may practise healthier lifestyles than those who do not [8]. We, therefore, presumed that Burkinabè adults who were aware of their hypertensive status would have healthier lifestyle measures than those who were not. Using data from the first World Health Organization (WHO) stepwise approach to surveillance (STEPS) survey in Burkina Faso, we compared the distribution of lifestyle factors between the adults living with hypertension who were aware and unaware of their hypertensive status. We also assessed the factors associated with being aware of one’s hypertensive status.

Methods

Description of the Burkina Faso STEPS survey

The WHO STEPS surveys use a standardized tool for data collection which includes specific sections on behavioural risk factors (tobacco and alcohol consumption, oral hygiene practices, FV intake, physical activity); anthropometric [body mass index (BMI)] and blood pressure measurements; and blood biochemistry [9].

The first WHO STEPS survey in Burkina Faso, conducted from 3 September to 24 October 2013, was nationally-representative and covered all the country’s 13 administrative regions. It involved interviews on behavioural or lifestyle factors as well as anthropometric and blood pressure measurements [9]. As the detailed methodology including sample size calculation, sampling procedure and blood pressure measurements have been previously published [10, 11], only a brief description will be presented for this secondary data analysis study.

The survey enrolled adults aged 25–64 years, based on a calculated sample size, large enough to allow sub-group comparisons. The estimated sample size, based on an assumed prevalence of hypertension of 29.4, 5% precision, a design effect of 1.5 and 20% non-response, was 4785, and was rounded up to 4800. The sample was weighted by sex, age group, and rural/urban residence.

A stratified three-stage cluster proportional to the size sampling was used to select participants. The sample was stratified to provide adequate representation of both rural and urban residence. An excel spread sheet was used to draw households from each selected cluster. One individual aged 25–64 years was randomly selected from each household using the Kish method [12]. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in a language spoken by the participant and data captured using personal digital assistants pre-loaded with eSTEPS software.

Blood pressure was measured on the right arm with an electronic blood pressure monitor (OMRON HEM-705, Tokyo, Japan) with the patient seated upright with the legs uncrossed. The blood pressure was taken three times at five-minute intervals after the participant had initially rested for 15 minutes. The mean of the three blood pressure readings was used in the analysis of hypertension.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The protocol of the primary STEPS survey was approved by the Ethics Committee for Health Research of the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso (deliberation No: 2012–12,092; December 05, 2012). Written informed consent was systematically obtained from each participant in the STEPS survey.

As the current study did not involve human subjects, no ethical approval was necessary. The database for this secondary analysis, is freely available from the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso on request. As the study authors work with a national research health institute that is affiliated to the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso, there was no difficulty with access to the database.

Study variables

Sociodemographic data collected included living environment, sex, age, marital status, education level and occupation. Self-reported data on the modifiable lifestyle factors that were considered in the secondary data analysis were alcohol and/or tobacco use, oral hygiene practices, FV consumption, and physical inactivity. The anthropometric measurements were weight, height, as well as blood pressure.

Current alcohol consumption was defined as alcohol intake in the past 1 month while current tobacco use was defined as ever use of smoked or smokeless tobacco in the past 12 months [9, 13, 14]. The oral hygiene practices were categorized based on the frequency of cleaning teeth per day, with, at least twice daily cleaning being recommended [15]. Daily FV intake was derived from the number of servings of FV consumed per day during a typical week. Five or more daily FV servings is recommended [16]. Physical activity was investigated via the amount of time being physically active in three domains; transport, at work and during leisure time and participants were asked about the frequency, intensity and duration of their work-, travel- and leisure-related physical activity (vigorous or moderate), in a typical week [17]. We considered participants who reported no vigorous- or low- physical activity during a typical week as being physically-inactive. Body mass index (BMI), calculated as a subject’s weight divided by height2, in kg/m2, was characterized as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) overweight (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) or obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) states [18].

We defined persons living with hypertension as those with higher than or equal to 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure higher than or equal to 90 mmHg or those who reported current antihypertensive therapy use [1, 10]. Our outcome of interest for the secondary data analysis was the awareness of hypertension defined as participants with hypertension who reported having been told by a doctor or a health professional as having raised blood pressure or hypertension.

Statistical analyses

We used StataCorp Stata Statistical Software for Windows (Version 14.0, College Station, Texas, US) to analyse the data. The continuous variables were expressed as the means ± standard deviations, while the categorical variables were expressed as percentages (%) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Student’s t test was used to compare continuous variables, and the chi-square or the Fishers exact tests were used to compare categorical variables.

In the stepwise logistic regression models, we dichotomized the outcome variable as being aware or unaware of one’s hypertension status. The lifestyle factors were the explanatory variables, with adjustment on sociodemographic factors (sex, age, urban-rural residence, marital status, education and occupation). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was performed to determine the goodness-of-fit of the logistic regression models. Except for the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, for all analyses, a p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the sample of 4800 individuals enrolled in the primary study, 105 were not eligible; 10 had invalid data on sociodemographic variables. For our secondary data analysis, the numbers with missing or implausible data on lifestyle factors were as follows: 1 for tobacco, 6 for oral hygiene practice; 279 for FV intake, 205 for BMI, and 7 for blood pressure. After excluding these individuals and 3413 normotensive individuals, 774 individuals with hypertension and complete data were included in our analysis.

The mean age of these 774 persons was 43.8 ± 11.6 years. They were predominantly male (53.9%), rural residents (71.6%), illiterates (77.5%), or engaged in an occupation without formal income (92.0%) (Table 1).

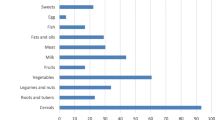

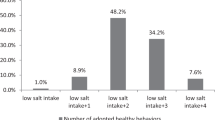

Overall, 84.9% (95% CI: 82.2–87.3) of them were not aware of their hypertensive status (Table 2). About 43% of persons living with hypertension had recently used alcohol or tobacco or both, 69.4% did not clean their teeth frequently, 11.4% were physically inactive, 95.7% consumed inadequate FV servings and 29.7% were overweight or obese.

The differences in the lifestyles between those aware and unaware of their hypertension with respect to alcohol or tobacco use, physical activity and BMI were statistically significant (Table 2). Those who were aware that they had hypertension were more likely than those with undiagnosed hypertension to have abstained from tobacco or alcohol (64.1% versus 57.7%, p = 0.027). They were, however, less likely to be physically active (82.9% versus 89.7%, p = 0.04) and more than twice as likely to be overweight or obese (53.8% versus 25.4%, p < 0.001). The differences in oral hygiene practices and daily FV intake were not statistically significant.

In multivariable analysis, participants with hypertension who were older, had primary education or higher, were overweight/obese, were currently using and had recently used alcohol/tobacco and those who consumed adequate FV servings were significantly more likely to report having been previously diagnosed as having hypertension (Table 3). The strongest predictors of being aware of one’s hypertension were older age, educational level and BMI status. Participants aged 55–64 years old were 7.2 times as likely as those aged 25–34 years to be aware of their hypertension. Those with secondary or higher education were 5.6 times as those with no formal education to be aware of their hypertension. Participants who were overweight/obese were 3.2 times as those with normal BMI to be aware of their hypertensive status. In contrast, marital status, occupation, physical activity and frequency of teeth cleaning were not significantly associated with awareness of one’s hypertension status. Regarding the goodness-of-fit test for this logistic regression model, the Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-square test yielded a p-value over 0.05.

Discussion

Our study revealed some important findings. First, we found that undiagnosed hypertension was very high (85%) among Burkinabè adults. Our finding is similar to that in Tanzania (90%) [19] and Cameroon (81%) [20] but higher that the reported levels of 78% in Angola [21], 76% in Guinea [22], 71% in Kenya [23], 65% in Ghana [24] and 60% in Nigeria [25]. The high level of undiagnosed hypertension could pose a high risk for cardiovascular complications. For example, in Nigeria, half of all acute stroke cases presented with undiagnosed hypertension [26]. More recently, the proportion of stroke due to undiagnosed hypertension in low-income countries (15.9%) was found to be about three times as high as that in high-income countries (5.6%) [27]. In acute medical care in Burkina Faso, a high prevalence of hypertension has been reported among patients with cardiocerebrovascular events: in 58%; 66%; 76 and 86% of patients with acute coronary syndromes [28] cardioembolic disorders [29] stroke [30] and non-valvular atrial fibrillation [31] respectively. Educational programs are, therefore needed to increase awareness and practice of healthier lifestyles and thereby reduce the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases [32].

Secondly, we found that the pattern of modifiable unhealthy lifestyle practices between adults living with hypertension in Burkina Faso who aware and unaware of their hypertensive status was mixed. Awareness of hypertension among Burkinabe adults did not necessarily translate into healthier lifestyles. This has also been the experience elsewhere where greater awareness of hypertension did not always translate into better treatment and control of hypertension [33] or healthier lifestyles [34]. Those aware of their hypertension being more likely to be non-current or recent users of alcohol or tobacco, consumers of adequate FV servings daily but then significantly more likely to be overweight/obese.

Our findings of healthier smoking and alcohol use habits among adults aware of their hypertension agree with those of others. Participants who aware of their hypertension were more likely to reduce their alcohol consumption in Korea [8] and to accept smoking cessation in Nigeria [35]. Similarly, undiagnosed adults with hypertension in Ghana, were more likely to be current users of alcohol or tobacco [32]. Hence, improving the diagnosis of hypertension through measures such as opportunistic screening at health facilities and in communities to identify asymptomatic persons with hypertension and counselling them on harmful effects of tobacco and alcohol use are needed.

As in our study, overweight/obesity was associated with a lower risk of undiagnosed hypertension in six LMICs [36]. It is gratifying that those overweight/obese, a known risk factor for hypertension, were also more likely to be aware of their hypertension. Overweight and obese may have co-morbidities that increase their encounters with healthcare professionals and their opportunity to learn about their hypertensive status.

Thirdly, we found that a very low frequency of adequate FV intake. The low FV intake reflects the general low FV consumption ranging from 79 to 96% in West African countries [37]. FV consumption is considered to protect against hypertension [38] and stroke [39]. There is, therefore, the need for systematic dietary programmes to improve FV intake from childhood. The challenge is the ingrained cultural taste and dietary preferences among Africans, even when the food habit is known to be unhealthy [40].

Being aware of one’s hypertension diagnosis did not appear to influence physical activity or oral hygiene practices among Burkinabe adults. A similar finding has been reported in Ghana [32] as well as in Sudan where regular exercise was found to be the most challenging lifestyle change for hypertensive subjects [41]. Low adherence rates for either weight control or exercise have been commonly reported in individuals with hypertension [8] resulting in uncontrolled hypertension [42].

Healthy oral hygiene practices including frequent tooth brushing improves dyslipidaemia, particularly high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride levels [43], and may help in the control of hypertension [44]. Choi et al. [45] demonstrated that systolic blood pressure levels progressively decreased as the frequency of toothbrushing increased. Nonetheless, there is insufficient knowledge about adequate management of patients with hypertension in dental practice [46]. Preventive dental interventions could be used to reduce the development of hypertension [7]. Awareness programs to promote oral health may have benefits on blood pressure level in general population [47].

The strengths of our study include the large representative sample and the use of standard definitions of variables. Our study also has some limitations. First, there was a high number of missing data for certain lifestyle variables. Secondly, awareness was self-reported and could not be independently verified. Thirdly, there were several variables such as salt intake [8], psychological stress and sleep quality [48] for which data were not available and so could not be included in the regression model. Fourthly, there should be caution in the interpretation of our findings due to possible reverse causality in a cross-sectional design. For example, it is not clear whether FV intake preceded or was as a result of hypertension. Finally, the level undiagnosed hypertension in 2013 may not reflect the current situation although it provides a relevant baseline against which future national surveys may be compared. A second national STEPS survey in Burkina Faso has recently been completed with analysis pending.

Conclusion

The prevalence of undiagnosed hypertension is very high among Burkinabè adults. Whereas most participants were physically active, most did not consume adequate amounts of fruits and vegetables daily. Participants living with hypertension who reported being aware of their condition did not necessarily practise healthier lifestyles than those who had not been previously diagnosed. Further analysis is required to assess how awareness of hypertension relates to the control of hypertension. Current educational programmes for hypertension control should be intensified, starting from childhood with the aim of improving awareness and adoption of healthier lifestyles from an early stage.

Availability of data and materials

The database of the STEPS survey used for this secondary analysis is available at the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso and can be requested from bicababrico78@gmail.com.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratios

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- cOR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- FV:

-

Fruits and/or vegetables

- kg/m2 :

-

Kilogramme per square metre

- LMICs:

-

Low and middle-income countries

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- STEPS:

-

Stepwise approach to surveillance

- US:

-

United States

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, Riley LM, Paciorek CJ, Stevens GA, et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398:957–80.

Schmidt B-M, Durao S, Toews I, Bavuma CM, Hohlfeld A, Nury E, et al. Screening strategies for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:CD013212.

Ataklte F, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Taye B, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Kengne AP. Burden of undiagnosed hypertension in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2015;65:291–8.

Saptharishi L, Soudarssanane M, Thiruselvakumar D, Navasakthi D, Mathanraj S, Karthigeyan M, et al. Community-based Randomized Controlled Trial of Non-pharmacological Interventions in Prevention and Control of Hypertension among Young Adults. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:329–34.

Hackam DG, Khan NA, Hemmelgarn BR, Rabkin SW, Touyz RM, Campbell NRC, et al. The 2010 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part 2 - therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:249–58.

Schutte AE, Srinivasapura Venkateshmurthy N, Mohan S, Prabhakaran D. Hypertension in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Circ Res. 2021;128:808–26.

Iwashima Y, Kokubo Y, Ono T, Yoshimuta Y, Kida M, Kosaka T, et al. Additive interaction of oral health disorders on risk of hypertension in a Japanese urban population: the Suita Study. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:710–9.

Kim Y, Kong KA. Do Hypertensive Individuals Who Are Aware of Their Disease Follow Lifestyle Recommendations Better than Those Who Are Not Aware? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136858.

World Health Organization. WHO steps surveillance manual: the WHO stepwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Soubeiga JK, Millogo T, Bicaba BW, Doulougou B, Kouanda S. Prevalence and factors associated with hypertension in Burkina Faso: a countrywide cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:64.

Diendéré J, Zéba AN, Kiemtoré S, Sombié OO, Fayemendy P, Jésus P, et al. Associations between dental problems and underweight status among rural women in Burkina Faso: Results from the first WHO STEPS survey. Public Health Nutr. 2021;1–30.

Wiegand H, Kish L. Survey Sampling. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, London 1965, IX + 643 S., 31 Abb., 56 Tab., Preis 83 s. Biom Z. 1968;10:88–9.

Francis JM, Grosskurth H, Changalucha J, Kapiga SH, Weiss HA. Systematic review and meta-analysis: prevalence of alcohol use among young people in eastern Africa. Tropical Med Int Health. 2014;19:476–88.

Delnevo CD, Villanti AC, Wackowski OA, Gundersen DA, Giovenco DP. The influence of menthol, e-cigarettes and other tobacco products on young adults’ self-reported changes in past year smoking. Tob Control. 2016;25:571–4.

Claydon NC. Current concepts in toothbrushing and interdental cleaning. Periodontol. 2000;2008(48):10–22.

World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization. Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation: World Health Organization; 2003.

Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6:790–804.

World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Technical Report 894. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

Mosha NR, Mahande M, Juma A, Mboya I, Peck R, Urassa M, et al. Prevalence, awareness and factors associated with hypertension in North West Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1321279.

Lemogoum D, Van de Borne P, Lele CEB, Damasceno A, Ngatchou W, Amta P, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among rural and urban dwellers of the Far North Region of Cameroon. J Hypertens. 2018;36:159–68.

Pires JE, Sebastião YV, Langa AJ, Nery SV. Hypertension in Northern Angola: prevalence, associated factors, awareness, treatment and control. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:90.

Camara A, Baldé NM, Diakité M, Sylla D, Baldé EH, Kengne AP, et al. High prevalence, low awareness, treatment and control rates of hypertension in Guinea: results from a population-based STEPS survey. J Hum Hypertens. 2016;30:237–44.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among adults in Kenya: cross-sectional national population-based survey. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26:923–32.

Bosu WK, Bosu DK. Prevalence, awareness and control of hypertension in Ghana: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0248137.

Odili AN, Chori BS, Danladi B, Nwakile PC, Okoye IC, Abdullahi U, et al. Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment and Control of Hypertension in Nigeria: Data from a Nationwide Survey 2017. Glob Heart. 2020;15:47.

Bwala SA. Stroke in a subsaharan Nigerian hospital--a retrospective study. Trop Dr. 1989;19:11–4.

O’Donnell M, Hankey GJ, Rangarajan S, Chin SL, Rao-Melacini P, Ferguson J, et al. Variations in knowledge, awareness and treatment of hypertension and stroke risk by country income level. Heart. 2020:heartjnl-2019-316515.

Kaboré EG, Yameogo NV, Seghda A, Kagambèga L, Kologo J, Millogo G, et al. Evolution profiles of acute coronary syndromes and GRACE, TIMI and SRI risk scores in Burkina Faso. A monocentric study of 111 patients. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). 2019;68:107–14.

Samadoulougou KA, Mandi DG, Yameogo YRA, Yameogo NV, Millogo RG, Kaboré WH, et al. Cardio embolic stroke: Data from 145 cases at the Teaching Hospital of Yalgado Ouedraogo, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Int J Cardiovasc Res. 2016;2015.

Labodi LD, Kadari C, Judicael KN, Christian N, Athanase M, Jean KB. Impact of Medical and Neurological Complications on Intra-Hospital Mortality of Stroke in a Reference Hospital in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). J Adv Med Biomed Res. 2018:1–13.

Samadoulougou KMDG. Non Valvular Atrial Fibrillation Related Ischaemic Stroke at the Teaching Hospital of Yalgado Ouédraogo, Burkina Faso. J Vasc Med Surg. 2015;03.

Anto EO, Owiredu WKBA, Adua E, Obirikorang C, Fondjo LA, Annani-Akollor ME, et al. Prevalence and lifestyle-related risk factors of obesity and unrecognized hypertension among bus drivers in Ghana. Heliyon. 2020;6:e03147.

Ekwunife OI, Udeogaranya PO, Nwatu IL. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in a nigerian population. Health. 2010;02:731–5.

Akbarpour S, Khalili D, Zeraati H, Mansournia MA, Ramezankhani A, Fotouhi A. Healthy lifestyle behaviors and control of hypertension among adult hypertensive patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8:8508.

Okwuonu CG, Emmanuel CI, Ojimadu NE. Perception and practice of lifestyle modification in the management of hypertension among hypertensives in south-east Nigeria. Int J Med Biomed Res. 2014;3:121–31.

Basu S, Millett C. Social epidemiology of hypertension in middle-income countries: determinants of prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, and control in the WHO SAGE study. Hypertension. 2013;62:18–26.

Bosu WK. An overview of the nutrition transition in West Africa: implications for non-communicable diseases. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015;74:466–77.

Li B, Li F, Wang L, Zhang D. Fruit and Vegetables Consumption and Risk of Hypertension: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:468–76.

He FJ, Nowson CA, MacGregor GA. Fruit and vegetable consumption and stroke: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Lancet. 2006;367:320–6.

Tateyama Y, Musumari PM, Techasrivichien T, Suguimoto SP, Zulu R, Dube C, et al. Dietary habits, body image, and health service access related to cardiovascular diseases in rural Zambia: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212739.

Abdalla AA. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards therapeutic lifestyle changes in the management of hypertension in Khartoum State. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2021;32:198–203.

Aberhe W, Mariye T, Bahrey D, Zereabruk K, Hailay A, Mebrahtom G, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension among adult hypertensive patients on follow-up at Northern Ethiopia, 2019: cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:187.

Holmer H, Widén C, Wallin Bengtsson V, Coleman M, Wohlfart B, Steen S, et al. Improved General and Oral Health in Diabetic Patients by an Okinawan-Based Nordic Diet: A Pilot Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E1949.

Kim N-H, Lee G-Y, Park S-K, Kim Y-J, Lee M-Y, Kim C-B. Provision of oral hygiene services as a potential method for preventing periodontal disease and control hypertension and diabetes in a community health centre in Korea. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26:e378–85.

Choi HM, Han K, Park Y-G, Park J-B. Associations Among Oral Hygiene Behavior and Hypertension Prevalence and Control: The 2008 to 2010 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol. 2015;86:866–73.

Sproat C, Beheshti S, Harwood AN, Crossbie D. Should we screen for hypertension in general dental practice? Br Dent J. 2009;207:275–7.

Ghani F, Tahir Z, Mukhtar N, Yaqub T, Bibi T. Oral Health Assessment, an Epidemiological Survey among Dental Patients from Lahore, Pakistan. SAJLS. 2018;6.

Franzen PL, Gianaros PJ, Marsland AL, Hall MH, Siegle GJ, Dahl RE, et al. Cardiovascular reactivity to acute psychological stress following sleep deprivation. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:679–82.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Ministry of Health for providing them with the STEPS survey database.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JD, JK, ANZ and WKB contributed to drafting the manuscript, JD and WKB performed the statistical analysis, SWJ, PVO, AAS, FG and AM, provided the first interpretation of the results, JD and WKB reviewed the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The protocol of the primary STEPS survey was approved by the Ethics Committee for Health Research of the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso (deliberation No: 2012–12092; December 05, 2012). Written informed consent was systematically obtained from each participant in the STEPS survey.

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Diendéré, J., Kaboré, J., Bosu, W.K. et al. A comparison of unhealthy lifestyle practices among adults with hypertension aware and unaware of their hypertensive status: results from the 2013 WHO STEPS survey in Burkina Faso. BMC Public Health 22, 1601 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14026-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14026-7